ONE OMINOUS “message in a bottle” from the Media burglars remained a secret—COINTELPRO. Despite having demonstrated inside the bureau in September 1971 that he was still a master at subterfuge, it was not possible for the director and his top aides to rest easy that fall. They were determined to stay the course, but they also feared daily that the worst was yet to come. What if someone was able to figure out what COINTELPRO was?

COINTELPRO hovered over the FBI.

The possible exposure of the program was regarded inside the bureau as the most dangerous bureau operation that could be exposed. It was assumed by bureau officials that the public’s reaction to it would be much more explosive than the reaction to the Security Index had been. As threatening as the Security Index was, people inside the FBI realized that if COINTELPRO became known, people would realize that the bureau conducted operations far more controversial and damaging to Americans’ rights than creating lists of alleged subversives to be arrested during a national emergency. For that reason, FBI officials desperately hoped in the spring of 1971 that COINTELPRO never would become public, that it would remain buried in the bureau’s most secret files. But they lived with a grim truth throughout that spring: The Media burglars were still free and were able to distribute files at any time, and for all FBI officials knew, the burglars might have a file that would reveal the existence of COINTELPRO.

Clever as the director had been through the years in protecting himself and the bureau, he would have realized that if COINTELPRO records became public, it would be impossible for him to avoid responsibility. Unknown outside the bureau, there was a long trail of secret files that provided detailed evidence that Hoover himself created the COINTELPRO operations, sought proposals for them, and had authorized and monitored most of them. Not only that, but he had put a premium on the development of COINTELPRO projects. Only the best agents were to be permitted to conduct them, and they would be rewarded for doing so. He had kept these operations a secret from most attorneys general he served under, including the current one—not that Attorney General Mitchell would have opposed them.

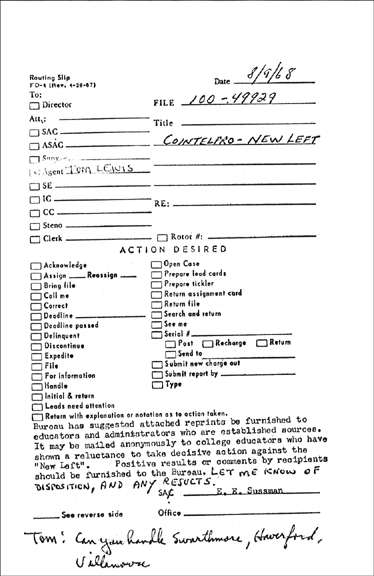

The only Media file that mentioned COINTELPRO arrived in my mailbox on April 5, 1971. The term was near the top of a routing slip that included the request that agents distribute the attached article that had been published in Barron’s, the weekly financial publication, on how campus protests should be handled more forcefully by college presidents. There was no clue about what the term “COINTELPRO” meant, but simply reporting about the file that contained the term set off an alarm inside the FBI. To bureau officials, a very important shoe had just dropped. As soon as my story about that file—written without the unexplained “COINTELPRO” term—was published on April 6, headquarters officials realized that one of their worst fears, public exposure of COINTELPRO, had just come closer to being realized. They had been waiting to see if that file would be released by the burglars. When it was, they knew then with certainty that the term existed outside the FBI for the first time. Something had to be done. My story on the files that arrived that day from the burglars emphasized the one with the COINTELPRO routing slip and was headlined “FBI Secretly Prods Colleges on New Left.” On a copy of the story included in the MEDBURG investigative file, Hoover handwrote three brief notes, each one a request for documents mentioned in the story.

This document, a simple routing slip, had more impact than any other file stolen from the Media office. The term at the top, COINTELPRO, had never been seen before outside the bureau. It was the name of one of Hoover’s most carefully guarded secrets—dirty tricks operations conducted against dissidents.

He acted quickly. On the same day the story was published, he wrote to the heads of all the field offices then conducting COINTELPRO operations and told them that the program’s “90-day status letters will no longer be required and should be discontinued.” That change suggested that the director was trying to increase secrecy about the program by eliminating one of the layers of reporting that documented progress in COINTELPRO operations. But in that same memorandum to field offices he also made it clear that COINTELPRO was still an important program despite the potential danger that could result from its name now being known outside the bureau. He told the agents in charge of the field offices that they must “continue aggressive and imaginative participation in the program.”

Two days after he learned that the COINTELPRO routing slip had been released by the burglars, Hoover wrote a letter to the attorney general. His April 8 letter to Mitchell seemed to be designed as a warning that something new and controversial might emerge at any time from the Media files. Specifically, he expressed concern that the burglars might make COINTELPRO public, but he did not mention the routing slip that already had been released. He informed the attorney general that the term, used alone, did not make the program “readily comprehensible.” Perhaps still hoping that the routing slip would spark no interest and COINTELPRO would remain secret, even from the attorney general, Hoover did not explain the nature of COINTELPRO operations, only that they existed.

By three weeks after the bureau learned from my story that the COINTELPRO routing slip had been released, concern at FBI headquarters apparently had increased dramatically about the possible exposure of the program. Hoover made a radical decision: he eliminated those programs he had started in 1956 and that he regarded as so important to his intelligence operation.

He took that extreme step after FBI official Charles Brennan wrote a memo to him on April 27, 1971, recommending the closure of COINTELPRO. This should be done, Brennan wrote, in order “to afford additional security to our sensitive techniques and operations.…These programs involve a variety of sensitive intelligence techniques and disruptive activities, which are afforded close supervision at the Seat of Government [a bureau term for the national FBI headquarters in Washington]. They have been carefully supervised with all actions being afforded prior Bureau approval and an effort has been made to avoid engaging in harassment. Although successful over the years, it is felt they should now be discontinued for security reasons because of their sensitivity.” Beginning three years later, as some COINTELPRO operations were revealed for the first time, it would be discovered that the operations not only did not avoid harassment but were designed specifically to be harassment, often of law-abiding Americans, sometimes for years and sometimes by provoking violence.

The director immediately agreed with the recommendation to close COINTELPRO. On April 28, he sent a memorandum to field offices ordering the immediate discontinuance of all COINTELPRO operations. Given the importance of COINTELPRO to the FBI, this would appear to have been a profoundly significant decision, one that would be disruptive to some of the major operations of the bureau. That was not a problem, however, for just as changing the name of the Security Index and its predecessor, the Custodial Detention Index, were ruses to cover his earlier defiance, the internal announcement that COINTELPRO was being closed was not what it appeared to be.

When the details of COINTELPRO started to be revealed, more than two years later, reporters at first accepted the FBI’s official statement that the program no longer existed, that it had been canceled on April 28, 1971. That was not true. Consistent with past Hoover practice, his order to eliminate COINTELPRO was designed to protect and to deceive. Once again the devil was in Hoover’s nomenclature. The program was no longer called COINTELPRO, but the program itself, with all the same qualities and practices, continued. From now on, Hoover wrote when he notified FBI officials that he had “closed” COINTELPRO, such operations would be conducted on an ad hoc basis, each approved by the director. That was exactly how they had been operated before. The only difference was that now the operations did not have the COINTELPRO designation. Therefore, if someone asked—as people did, beginning a year after the burglary—FBI officials would be able to say—as they did—“That program doesn’t exist anymore.” But it did.

New COINTELPRO-like operations, in fact, continued to be initiated at that time in 1971, including efforts to destroy the reputation of John Kerry, after he testified before Senator J. William Fulbright’s Senate Foreign Relations Committee and called the war in Vietnam “a tragic mistake.” The FBI eventually created a 2,934-page file on Kerry—the future Massachusetts senator, 2004 Democratic presidential candidate and secretary of state—and a 19,978-page file on Vietnam Veterans Against the War, the prominent organization of veterans returning from Vietnam he led in 1971. In fact, many such operations were conducted against individuals and organizations throughout the mid-1970s.

Given that the COINTELPRO operations had not been revealed by May 2, 1972, the day Hoover died, a little more than a year after the term surfaced on a Media file, he may have remained confident until his death that the program, perhaps his darkest secret, would remain hidden forever. That COINTELPRO had not been revealed by then may have convinced Hoover that the legacy he had spent a lifetime developing might not be redefined by what the Media files revealed or by the accusations a few former agents made against him in the last two years of his life—or by the powerful secrets he knew had not yet been revealed. Maybe those secrets would remain sealed.

HOOVER’S STRONGEST SUPPORTERS pulled out all the stops in the spring of 1971 to buoy his spirits. They encircled him with warm support and angry defenses in that year that was marked by harsh public criticism—a time that was what New York Times columnist Tom Wicker described in an April 15, 1971, column as “the worst period of controversy Mr. Hoover has encountered in his 47-year career.”

Thanks to a campaign by the bureau’s public relations office, on May 10, 1971, the forty-seventh anniversary of Hoover’s becoming director of the bureau, seventy-one members of Congress placed tributes to him in the Congressional Record.

Some of the extremely critical reaction that spring was from unexpected sources. Two publications that over many years had written only laudatory commentary about the director, Time magazine and Life magazine, delivered harsh criticism after the burglary. There was evidence, Time reported, that Hoover’s “fiefdom,” the FBI, was “crumbling, largely because of his own mistakes. The FBI’s spirit is sapped, its morale low, its initiative stifled.” The FBI had become, according to Time, “a secretive, enormously powerful Government agency under dictatorial rule, operating on its own, answerable to no authority except the judgments—or whims—of one man.”

On April 9, just a month after the burglary and two weeks after the first stolen files became public, Life ran a striking image of the director on its cover. It was a portrait of a sculpture of Hoover as a Roman emperor, complete with toga, with the title “The 47-year Reign of J. Edgar Hoover: Emperor of the FBI.” Inside the magazine, the headline was, “After almost half a century in total and imperious charge: G-Man under fire.” Pointing to reaction to recent revelations, Life noted that “the thrust of the criticism appears to be changing, and Mr. Hoover has drawn the attention of more powerful critics. Now he has been challenged—of all places—on the floor of the House. It has been widely charged that the director’s imperious disregard for any but his own views of the national interest diminishes his Bureau’s effectiveness and has even become a serious infringement on civil rights.”

A month after the Life cover appeared, Hoover made a rare public appearance. He spoke at a dinner sponsored by the American Newspaper Women’s Club in Washington. He had accepted an invitation to introduce the person who would be honored that evening, Martha Mitchell, the wife of the attorney general. She was a prominent personality and a favorite of the Nixon administration at the time because of her frequent brash and funny public comments about whatever was on her mind. Later, when she called reporters in the middle of the night with inside secrets about Watergate crimes, she was considered a liability to the Nixon administration who had to be hushed. But now, in the spring of 1971, when Hoover warmly introduced her, she was still considered an amusing asset. She urged the audience to look at Mr. Hoover carefully that evening, for “when you’ve seen one FBI Director, you have seen them all.”

In a rare jovial mood, Hoover nearly matched Martha Mitchell’s ability to draw laughs. “I know that those of you who subscribe to an alleged national magazine may have had some difficulty recognizing me in the conventional clothes I am wearing this evening. But, like ordinary people, we emperors do have our problems, and I regret to say that my toga did not get back from the cleaners on time.”

President Nixon defended Hoover a month after the burglary when he answered questions at the annual convention of the American Society of Newspaper Editors, the same convention where CIA director Helms denied the CIA conducted domestic spying. Asked by one of the editors to comment on the fact that “J. Edgar Hoover very recently seems to have become one of the favorite ‘whipping boys’ of a number of prominent Americans,” Nixon responded angrily. The criticisms of Hoover, he said, “are unfair … and malicious.…I would ask the editors of the nation’s papers to be fair about the situation. He, like any man who is a strong man and an able man … has made many enemies.…He has been nonpolitical … nonpartisan. Despite all of the talk about surveillance and bugging and the rest, let me say I have been in police states, and the idea that this is a police state is just pure nonsense. And every … paper in the country ought to say that.…As long as I am in this office, we are going to be sure that not the FBI or any other organization engages in any [surveillance] activity except where the national interests or the protection of innocent people requires it, and then it will be as limited as it possibly can be.” As Nixon made those comments that day, his own secret plans to greatly increase political surveillance and dirty tricks against his perceived enemies were well under way.

The hundreds of newspaper editors assembled in the convention hall that day with Nixon accepted the president’s observations without questioning him. Many of them may have been surprised when Washington journalists later reported stories about not only the dirty tricks of Hoover’s FBI but also those of the Nixon Plumbers team.

Throughout that awful year in Hoover’s life, he was defended repeatedly by former FBI agents—individually and by the Society of Former Agents of the FBI. Organized in 1937, the society now rallied around him at meetings throughout the country. Members in chapter after chapter unanimously passed resolutions backing the director. With 5,500 members at the time, the society had been fairly independent of FBI headquarters until 1964, when the director and the society decided they needed each other and established a formal bond. They entered into an agreement that members of the society would be deputized to help the bureau round up the thousands of people listed on the Security Index in the event of a national emergency. Otherwise, the society was primarily a source of fellowship and was an informal but very valuable high-level employment agency for former agents. It found jobs for former agents in security positions and high-level executive positions in American corporations, where many former agents landed. For example, John S. Bugas, the former head of the Detroit FBI office, upon retiring from the bureau became vice president of Ford Motor Company and a close friend and aide of Henry Ford II. Such connections often were either a personal or a professional benefit to the bureau. One of the benefits of the close connection with Ford was that the corporation paid for various special events for the FBI, including a banquet at the society’s 1970 national convention at Disneyland, where the guest of honor was Efrem Zimbalist Jr., star of the The F.B.I., the very popular weekly television series sponsored by Ford. Hoover was there and, as usual, treated Zimbalist like he was not only a real FBI agent but FBI agent number one. At Hoover’s invitation, Zimbalist often spoke at various gatherings of agents, including the graduation ceremony of new agents.

The society’s members tended to be politically conservative. Some were extremely right-wing, such as Willard Cleon Skousen, a John Birch Society official who wrote The Naked Communist in 1958 and whose ideas have been promoted in recent years by commentator Glenn Beck and by some Tea Party leaders. Some other former agents in the society created private organizations that specialized in using the skills they had learned in the bureau, including planting rumors about politicians Hoover did not like. Senator William Proxmire of Wisconsin, Senator George McGovern, Senator William Fulbright, and Senator Edward Kennedy were favorite targets.

After the Media burglary, Hoover could not have asked for more from ex-agents. On April 17, 1971, the North Central chapter of the society adopted a resolution that praised the director’s record and deplored the allegations of his critics. Given extensive coverage by the press, the resolution said there was no basis “to the criticism by some” that “the FBI has become oppressive in its investigative activities and is becoming a threat to the civil liberties of citizens.…We know without any question that the FBI, under the most explicit direction of Mr. Hoover, has jealously protected the nation against any invasion of these liberties.”

The president of the North Central chapter, Duane Traynor, released this statement: There was “no fairer man who ever lived or was more attuned to the needs of the nation than Mr. Hoover.” In the society’s spring 1971 newsletter, the Grapevine, a column charged that a “strongly suspected undercover conspiracy” to smear Hoover had been hatched by everyone from “anarchist revolutionaries” to “bleeding-heart liberals.” At the former agents society’s annual national convention in Atlanta that year, the members passed a vote of confidence in Hoover against “vicious and unwarranted attacks” that were “politically motivated.”

So many people signed up in the spring of 1971 to support the director by attending the society’s annual Congressional Night dinner in Washington that the event had to be moved from the Rayburn House Office Building to a larger space at the Shoreham Hotel. The Grapevine reported that the April 1971 Congressional Night dinner, attended each year by society members and members of Congress, “developed into an evening of serious commentary about numerous recent scurrilous attacks against the FBI and Director J. Edgar Hoover.” Those present included former FBI official and then head of the Defense Intelligence Agency Joseph F. Carroll and seven members of Congress who were former FBI agents. Hoover didn’t usually attend this annual dinner, but he did now when he was under attack. When Carroll introduced the director that evening, he received a standing ovation that lasted several minutes.

Hoover spoke harsh words that night. He attacked the “few journalistic prostitutes” who could not appreciate the FBI. He assured the former agents and others in the audience that the FBI would not compromise its standards “to accommodate kooks, misfits, drunks and slobs.”

“It is time we stopped coddling the hoodlums and the hippies who are causing so much serious trouble these days,” he said. “Let us treat them like the vicious enemies of society that they really are, regardless of their age.”

The director was given more public accolades from President Nixon two months after he had defended him to the newspaper editors. He and Attorney General Mitchell both spoke at the ceremony that marked the graduation of police officers from the FBI Academy on June 30, 1971. The president told the young police officers from throughout the country that more than twenty years earlier, as a young member of Congress from California, he had worked with Hoover on “major investigations of various subversive elements in this country.” Regarding current attacks on the director, the president said, “Anybody who is strong, anybody who fights for what he believes in, anybody who stands up where it is tough is bound to be controversial.…The great majority of the American people back Mr. Hoover.”

In what Nixon later said was the strongest part of his defense of Hoover that day, he told the graduates that “he is a man who has never served a party, he has always served his country.” Nixon assured the police officers that, like the director, he and the attorney general “back law enforcement officials in their attempts to reestablish respect for the law.”

A remarkable series of expressions of both contempt and respect for the law took place in exchanges at the White House that day and the next. After telling the young police officers about his deep respect for the law and the need to reestablish the rule of law, the next evening the president, according to White House tapes, ordered White House chief of staff H. R. Haldeman to have someone break into the Brookings Institution and steal material related to the conduct of the Vietnam War. The president was forceful in his recommendation: “Just break in. Break in and take it out! You understand? Just go in and take it! … Go in around 8 or 9 o’clock … and clean it up.”

White House aide Charles Colson was recorded that day proposing that the Brookings burglary be accomplished by firebombing the think tank. As firefighters would rush to the scene, he said, they would supply cover for FBI agents, working on behalf of the White House, to enter the building and steal the documents, presumably while the firefighters were putting out the fire. That criminal favor would be done by the FBI, aides confidently predicted, on the orders of the FBI director the president had just publicly insisted to young police officers never served the interest of a political party.

Only a few hours before Nixon gave bold advice on how to break into Brookings, he and Hoover discussed the events of the previous day in a phone conversation. Hoover thanked the president for his generous remarks at the graduation ceremony. He said the president’s remarks were especially meaningful at this time when he “was being attacked from many sides.” They commiserated with each other about the U.S. Supreme Court decision that was issued while Nixon was at the ceremony at the FBI—the decision supporting the right of the New York Times and the Washington Post to publish the Pentagon Papers. The decision inspired them to air their mutual low regard for the court:

PRESIDENT NIXON: I wanted to tell you I was so damn mad when that Supreme Court had to come down.…I didn’t like their decision.

DIRECTOR HOOVER: It was unbelievable.

PRESIDENT NIXON: You know, those clowns we got up there. I’ll tell you, I hope I outlive the bastards.

DIRECTOR HOOVER: Well, I hope you do, too.

PRESIDENT NIXON: I mean politically, too. Because, by God—we’ve got to change that court.

DIRECTOR HOOVER: There’s no question about that whatsoever.

They both expressed regret that Nixon’s praise of Hoover at the FBI ceremony was not the leading story in newspapers the next day.

The president explained why it wasn’t:

PRESIDENT NIXON: If it hadn’t been for that stinking [Pentagon Papers] court decision we’d have been the lead story.

DIRECTOR HOOVER: And it should have been. Your remarks were simply wonderful.

Hoover told the president his praise was so wonderful that he had ordered that it be published in Law Enforcement Bulletin, a publication the bureau then distributed regularly to 15,000 police departments in the country.

PRESIDENT NIXON: Oh, heck.

They ended the conversation criticizing someone each of them obviously held in as low regard as they held the Supreme Court—Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham:

DIRECTOR HOOVER: I saw her on the TV last night. Mrs. Graham. I would have thought she’s about 85 years old. She’s only about, I think, something like 57.

PRESIDENT NIXON: She’s a terrible old bag.

DIRECTOR HOOVER: Oh, she’s an old bitch in my estimation.

PRESIDENT NIXON (LAUGHING): That’s right.

The president thanked the director for the cuff links, emblazoned with the FBI seal, he had given him the previous day.

BY THE FALL OF 1971, Hoover had two major fears. On October 1, Sullivan, after a series of raging arguments with the director, arrived at work and found that his name had been removed from his office door and the locks changed. He had been fired. Hoover knew that Sullivan, after more than thirty years of devoted service to him, including creating some of the worst of the COINTELPRO operations, knew essentially everything that could be used to destroy Hoover. Given that, Hoover added Sullivan, a loose cannon now that he was fired, to his other greatest fear at that time: the Media burglary. “Only those who worked for him,” wrote Gentry, “knew how shaken Hoover had been by the burglary of the small Pennsylvania agency.”

Comments about Hoover in the White House during those months often were not as generous or flattering, to put it mildly, as either the president’s public remarks or his private comments to Hoover had been. White House tapes that later became public reveal that the president and his top aides were eager for Hoover to retire. Their grievances against him were mounting. They thought he was too old for the job and was becoming senile. They resented him for letting his fear of being forced out of office make him less amenable to their requests for illegal operations.

They were downright harsh in their private assessments of him. “He should get the hell out of there,” Nixon said in an October 8, 1971, conversation with Mitchell. They considered asking him to retire, and if he would agree to do so, they would have a grand public celebration of his service as FBI director. Nixon had a meeting with Hoover in July 1971 for the purpose of asking him to step down. Hoover apparently anticipated what was afoot and spent the entire meeting filibustering Nixon about the past and about how well things were going at the FBI. Nixon said not a word to Hoover about retiring. As the director had done the previous year, he now outmaneuvered Nixon again. He left the Oval Office with his job intact and the president feeling doomed to live with Hoover as FBI director forever. Nixon also had a meeting with Hoover in October 1971 that he hoped would lead to his retirement. It did not.

The president was afraid of Hoover. He undoubtedly had the director’s April 1971 threat to blackmail him in mind in October 1971, when he said of Hoover, “We may have on our hands here a man who will pull down the temple with him, including me.” Finally, the president was told that he should not force Hoover to retire because of how the Catholic peace activists would capitalize on such a move.

It was G. Gordon Liddy—the former FBI agent then on the staff of the White House and one of the planners of the burglary of the 1972 break-in, for which he was convicted, at Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate—who ultimately convinced Nixon it would be dangerous to force Hoover to retire. Liddy wrote a detailed memo for the president that listed the pros and cons of removing Hoover from office, concluding that it would not be in the “best interest of the Nation, the President, the FBI and Mr. Hoover, that the Director retire before the end of 1971.” Fearful of the harm Hoover might do to him if he forced him to retire, the president concluded that Liddy had made a strong case for not removing Hoover. One of the reasons Liddy had given for not removing Hoover was that doing so would be seen during the 1972 Harrisburg trial of the Catholic peace activists whom Hoover had accused of plotting to bomb tunnels and kidnap Henry Kissinger as lending “weight to what are sure to be defense contentions of a conspiracy to justify Hoover’s accusations against the Berrigans.”

WHEN THE PRESIDENT LEARNED on the morning of May 2, 1972, that J. Edgar Hoover had been found dead in his bedroom early that morning, he immediately started to plan the funeral as a grand public occasion that would be televised. He would give the eulogy himself. The timing was not quite right. Nixon would have preferred that Hoover had died earlier in his first term so the appointment of his replacement would not become a battleground over Nixon’s law-and-order politics or over the FBI’s past. “The house cleaning [at the FBI] is going to come, but it should not come now because we can’t have any flaps about that now,” Nixon told L. Patrick Gray in the White House just hours after Hoover’s funeral. He had plucked Gray from the Department of Justice and appointed him acting director of the bureau the day after Hoover died. Newspaper commentary the day after Hoover’s death focused on the fact that now that Hoover had died, the bureau was likely to face “the most thorough public investigation in its history.”

As Nixon and H. R. Haldeman, White House chief of staff, discussed Hoover’s funeral, Nixon, in the absence of Hoover having a family, took over. Nixon said he would like for Hoover to be buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Haldeman suggested that was inappropriate inasmuch as Hoover in death, as in life, “the last thing he’d want is to be anywhere near Bobby Kennedy.” Both Robert Kennedy and his brother John were buried at Arlington. Nixon settled for what Hoover wanted, burial beside his parents in the family plot at Congressional Cemetery in southeast Washington, not far from his childhood home.

Hoover’s remains lay in state in the Capitol Rotunda the day after he died. He was only the twenty-second person, and the first civil servant, accorded that honor since the Rotunda was completed in 1824. Most of the others who had been given that high honor were presidents and select members of Congress and the military. A thousand people an hour filed past Hoover’s closed casket. Outside the Rotunda, a few hundred protesters quietly read the names of the thousands of Americans who had been killed in the Vietnam War. It was not reported whether they were being photographed by FBI agents or informers, as such demonstrations routinely were.

In the front pews at Hoover’s funeral at National Presbyterian Church in northwest Washington on May 4 were Chief Justice Warren Burger; Mamie Eisenhower, whose husband had been buried from the same church just two years earlier; John Mitchell, who recently had resigned as attorney general to become the director of the Committee to Re-elect the President; and Vice President Spiro Agnew, who would be forced out of office the next year and charged with political corruption and income tax evasion. Agnew released a statement saying Hoover was dear to Americans because of “his total dedication to principle and his complete incorruptibility.” Among the other dignitaries seated near the front of the church were two new Supreme Court justices, William Rehnquist and Lewis Powell, and Frank Rizzo, then the mayor of Philadelphia, formerly the police commissioner, and a longtime admirer of the director.

Among the couple thousand attendees were hundreds of FBI agents. Seated in the midst of them was Efrem Zimbalist Jr., the actor selected years earlier by Hoover to be the star of The F.B.I. Mark Felt, Hoover’s man at Media the morning after the burglary, was seated among the agents and was an honorary pallbearer. As of the previous day he had become the second-highest-ranking person in the bureau, taking the place of Tolson, who retired within hours of Hoover’s death. Felt, very disappointed that he was not appointed to succeed Hoover, would soon expand his power over day-to-day operations of the bureau while Gray was acting director. Felt also took over Hoover’s responsibility for editing and giving final approval to scripts of The F.B.I., sometimes spending several hours a day writing multipage single-spaced elaborate edits and critiques. He did this throughout the time he served as a high administrator at the bureau, including, beginning the following fall, during the period when he met Washington Post reporter Bob Woodward occasionally late at night in a dark garage in Arlington, Virginia, complicating the life of the man who gave the eulogy at Hoover’s funeral.

In his eulogy, Nixon expressed the highest praise for his longtime friend. “America has revered this man not only as the Director of an institution,” he said,

but as an institution in his own right. For nearly half a century, nearly one-fourth of the whole history of this Republic, J. Edgar Hoover has exerted a great influence for good in our national life. While eight presidents came and went, while other leaders of morals and manners and opinion rose and fell, the Director stayed at his post … helped to keep steel in America’s backbone, and the flame of freedom in America’s soul.

He personified integrity; he personified honor; he personified principle; he personified courage; he personified discipline; he personified dedication; he personified loyalty; he personified patriotism.…

The United States is a better country because this good man lived his long life among us these past 77 years. Each of us stands forever in his debt. In the years ahead, let us cherish his memory. Let us be true to his legacy.

The president concluded, “He loved the law of this country.”

Within the next two years, Americans would learn that neither of these two very powerful leaders, the president at the podium or the FBI director in the coffin, seemed to love the law very much.