POST-BURGLARY LIFE varied greatly for the Media burglars. Because they kept their promise not to be in touch with one another in order to minimize the likelihood of arrest of one leading to arrest of any other member of the group, they never knew the struggles each of them endured.

For Bob Williamson and Keith Forsyth, the youngest burglars, it was difficult to move ahead into normal lives after their resistance ended. It turned out that age made a difference in resistance. Unlike the older burglars, Forsyth and Williamson had to rebuild their lives and start over. The process involved profound changes, including disengaging from people and from issues they had cared about deeply. Rebuilding was at times a painful challenge. In different ways, each of them crashed before they found a satisfying new life.

For several years, both Forsyth and Williamson became so detached from their resistance past that they didn’t even realize what the Media burglary had accomplished—the chain of important revelations and reforms the burglary initiated. The other burglars privately experienced a growing sense of accomplishment throughout the 1970s as they absorbed the unfolding story of change and revelations at the FBI. In contrast, it would be more than a decade until either Forsyth or Williamson fully understood the significant impact of the burglary. Consumed during their resistance years with informing themselves daily about what was happening in Vietnam and Washington, after their resistance years they turned inward and took less interest in what was going on in their former world of antiwar political activism.

The different impact of the burglary on the younger burglars can be understood, to some degree, in the very different nature of the post-burglary daily lives of the older and younger burglars.

The older burglars were cushioned by daily obligations. They continued to go to work each day, all of them advancing in their careers over time. They continued to pay mortgages, make home repairs. They continued to nurture their children, play with them, watch their progress in school, watch their minds become curious, watch them learn to love. The daily tasks and responsibilities that absorbed them before the burglary continued to absorb them afterward. In a sense, there was no break for them.

For the younger burglars, there was a big break between their past in resistance and their unknown future. When their resistance ended, Williamson and Forsyth had no answer to the basic question, “What next?” The very thing it was assumed would make resistance easier for younger people—a lack of personal obligations and responsibilities—was actually what later made their lives more difficult. They had none of the daily obligations that often are not only a heavy burden but also the threads of the fabric that holds a life together, that gives a person a sense of purpose and fulfillment.

Because Williamson and Forsyth had dropped out of college to work to build opposition to the war, they had no traditional formal higher education degree, no career or even career plans, no commitment to an ongoing relationship, and no children who depended on them. When they gave up nearly everything to oppose the war full-time, they sacrificed developing the threads that weave a life together. As they made that sacrifice, it didn’t seem to matter to them. Their goal—waking up Americans to what was happening in Vietnam—was so important to them that they thought little at the time about what they were forgoing. They may not have even thought they were making a significant sacrifice. Forsyth and Williamson, like other people who dedicated themselves then to nonviolent resistance to the war, willingly lived modestly, reducing their needs so they could live on small incomes—Forsyth as a cabdriver, Williamson as a caseworker for a state agency—while they spent most of their time working on their primary commitment.

Williamson and Forsyth were also different from the older burglars in other ways. They did not grow up hearing about the Holocaust and having a burning desire to prevent such atrocities. They had no memories of the United States bombing Hiroshima. They were children during the early years of the civil rights movement in the South, though racial justice had become part of their burning desire to fight injustice. The roots of their resistance grew primarily from the Vietnam War and the tumultuous events of the late 1960s.

As Williamson puts it, they “came of age in a time of assassinations and war.” They grew up with a vague, and later gnawing and raw, awareness that major disasters were taking place: first the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963, then the assassinations in 1968 of Martin Luther King and Robert F. Kennedy; the massacre of hundreds of unarmed civilians at My Lai; and the killing of students at Kent State and Jackson State in 1970.

Forsyth and Williamson were children of American small towns that were supposed to be idyllic in every way, including lack of controversy. In Williamson’s Catholic home in Runnemede, New Jersey, and Forsyth’s Baptist home in Marion, Ohio, the Vietnam War—the issue that drove their resistance—was avoided. The war seemed to always hover in their families, as it did in homes throughout the country as sons and daughters started contesting their parents’ views of it. In such homes, the war often sat at the edges of family conversations, a subject that could cut and injure at any time.

With World War II a vivid memory, their parents desperately hoped war never would take place on American soil. That hope contributed to their solid support of the Vietnam War and to their belief, an echo of national leaders’ statements on war policy, that the United States should fight communism “there” so it would not have to fight it “here.”

Williamson and Forsyth stood out from the other Media burglars in another striking way. Five months after the Media burglary, both of them were arrested at Camden. Despite being acutely aware that even as they agreed to raid the Camden draft board, hundreds of agents were then frantically searching for the Media burglars—most intensively in the Powelton Village neighborhood where they lived—they decided to be part of the Camden group. They did so, of course, without knowing the FBI believed the Media burglars were part of the Camden burglars.

Camden affected Williamson and Forsyth in very different ways. Williamson immersed himself in the case, enjoying many aspects of trial preparation and the trial itself. Forsyth abandoned the group. He wanted to have as little connection as possible to the case. He was angry at himself for agreeing to participate in the raid. He regretted his decision to do so. He thought it was perhaps the most foolish thing he had ever done, especially in light of the fact that, almost from the moment he said yes, he thought the group was disorganized and headed for disaster. But for reasons not entirely clear to him, even years later, he did not drop out, not even after the informer, Robert Hardy, offered him a gun as they sat in Hardy’s truck, where conversations—unknown to Forsythe, of course—were piped directly to an FBI office and overheard by agents. Hardy suggested Forsyth might like to use it. Forsyth refused to touch it.

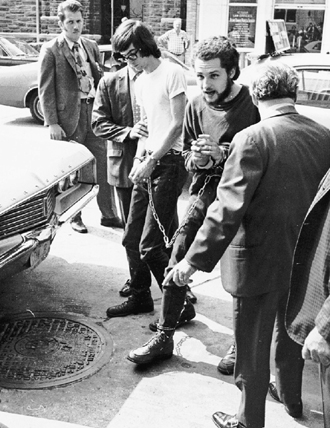

Federal agents arrest Keith Forsyth (third from right) the morning after the raid on the Camden draft board in August 1971. (Photo: Camden Courier-Post)

After the arraignment of the Camden defendants, Forsyth had very little contact with anyone in the Camden group and immediately started establishing a different focus in his life, a process that Williamson didn’t start until after the Camden trial. Forsyth stayed away from the trial. He did not even regularly follow news reports on the unusual developments taking place in the courtroom. He wanted to be away from it, both physically and emotionally. He chose to avoid thinking about the fact that he might be convicted for something he thought was ill-conceived and that he should not have joined. When the Camden trial ended, he was surprised and, of course, glad that he was acquitted instead of convicted. Still, he had little interest in what led to the unexpected acquittal. His interest would be rekindled in the group and the trial twenty years later. He would become involved in community and union organizing. He continued to oppose the war until it ended, but he no longer was an antiwar activist.

WILLIAMSON CONSIDERED CAMDEN his enduring safety valve. Media was a big secret he could not discuss, and living with that secret was sometimes an uncomfortable burden. Camden, on the other hand, was the opposite. Everything about it was completely open. Camden, especially with its not-guilty verdicts for all, was something very special he could discuss with anyone. He did so until, eventually, he got immersed in a new life.

He later looked back on the trial as having many positive aspects, including being fun. He enjoyed developing trial strategy, he enjoyed philosophical exchanges with all involved, and especially he enjoyed the warmth of the community of defendants. But the beginning of Camden, the night of the arrests, was not fun. Williamson doesn’t remember the details of some incidents from that period of his life, but he recalls his arrest that night with keen precision. He was standing on the parapet outside the window of the dark draft board office. From inside, other burglars were handing him large canvas bags stuffed with Selective Service records. He knew the file drawers and cabinets were almost empty and the job was about to end when suddenly—as he grabbed another large stuffed bag as it was hefted out the window and added it to the stack of bags on the parapet—he heard a loud clatter of feet below getting closer and closer as they rushed up the fire escape. He turned slightly and there, facing him, was a man, an FBI agent, pointing the barrel of his gun at Williamson. He recalls that it nearly touched his nose. The man and the other agents behind him yelled, “Freeze!” Again and again they yelled, “Freeze!”

“Just like in the movies. I mean really yelling. Deep guttural level. And so I did—I pretty much froze at that point.”

“I remember the feeling of being in shock and being numb.” One of the agents arrested him on the parapet. Then somehow, he doesn’t remember how, they pulled him through the window. The next thing Williamson remembers is that “we’re all laying on the floor.” He was facedown, with an FBI agent’s foot in the center of his back.

Williamson was stunned, but not surprised.

He had assumed that something like this was bound to happen since June 1969, when he attended the crucial meeting at Iron Mountain—the name John Peter Grady gave an old Episcopal church, St. George’s, in the Bronx, where some of the Catholic resisters occasionally met and where Grady’s unsuccessful 1968 campaign for Congress was based. It was at this meeting that some people in the Catholic peace movement decided to move from symbolic actions like the Catonsville Nine action in 1968 to clandestine actions, such as draft board raids conducted at night with the goal of actually—as opposed to symbolically—damaging the draft system and fleeing rather than waiting to be arrested.

Knowing that discussion of this critical change in strategy would take place at this meeting, Williamson immersed himself in the writings of highly respected advocates of nonviolent resistance—Henry David Thoreau’s essay “Civil Disobedience,” Louis Fisher’s biography of Mohandas Gandhi, and several writings by Martin Luther King. “I knew Gandhi had been a mentor to King, so I wanted to understand him.…It was against that backdrop that I went to this meeting. I went strongly committed to nonviolence and determined that nothing I would do would cause harm to anybody.”

He remembers that after lengthy and sometimes tense discussion, about half of the approximately twenty people there agreed that they felt they were likely to have more impact if they moved away from symbolic acts of resistance and engaged instead in clandestine actions designed to actually slow down the government’s ability to draft young men. People who attended the meeting recall that Daniel and Philip Berrigan opposed that change in strategy and continued to believe that symbolic public actions followed by immediately accepting responsibility were likely to have a more positive impact on the public.

As Williamson absorbed the thoughtful but difficult discussion, he decided to cast his lot with the group that wanted to do clandestine actions. He was impressed by the case made for that approach by various people, especially John Peter Grady. The Berrigans’ ideas still continued to permeate Williamson’s thinking about conscience and about the war, as they did for other people in this part of the peace movement, including the other people who went to Media.

After it was settled that some people supported and other people opposed the new strategy, Williamson recalls, the people who made a commitment to clandestine action stayed to discuss how they would move ahead—the caution needed, the potential dangers to such resisters and to people they might encounter inside draft boards. They discussed at length the harm they might inadvertently cause guards in federal buildings. They wrestled with the question of “what would happen if a guard walked in and caught us while we were in a draft board.” That concern arose from their belief, based on observation, that most guards in federal buildings were older men, people they assumed never expected anything to go wrong on the job. Given that, they feared the guards might be so shocked if they found burglars inside a draft board office when offices were closed that they would have a heart attack. That led to a lengthy discussion on how to be a calming influence in such a situation, on how to assure someone they were not being threatened. He does not recall that they discussed the possibility of a guard being armed and therefore a threat to burglars. Finally, Williamson says, Grady hammered home then and many times after that day the importance of being realistic about the personal consequences of these more aggressive nonviolent acts of resistance: that they might be arrested and pay a very heavy price. Williamson took that to heart and waited for it to happen. Arrest and imprisonment, he felt certain, would be the inevitable consequences of the decision he made that day.

WILLIAMSON’S THINKING had changed radically from the time he left Runnemede, his suburban hometown in the southwestern part of New Jersey, until the day of the meeting in the Bronx. He appreciated his hometown and realized his parents had provided what seemed like the perfect environment, a good home for their children in a community that had good schools and streets where children could ride their bicycles any time of the day and be safe. The perfect nature of his world was pierced for him for the first time when President Kennedy was assassinated. “Until that time I was very insulated and protected.…I had the sense that nothing bad would ever happen in the world.…I grew up in such a way that I wasn’t aware that bad things happen.” The assassination of President Kennedy “planted the seed of a kind of—the word that comes to mind is ‘realism.’ I really did live a very insulated life as I was growing up. Children think in almost magical terms. Well, I guess I had a sort of magical sense that God was looking out for all the good people, and that they would all be protected.…So when Kennedy was killed it was a tremendous shock. I think it was the beginning of a realization that the world was not always a nice place. That there was in fact evil and it could touch our lives.”

Williamson absorbed and expressed the dominant views of his small town. As a high school junior, he wrote and delivered a speech critical of draft card burners for the American Legion Oratorical Contest.

Short and very thin then as now, after Williamson was introduced at a Legion speech competition, he would slowly walk toward the center of the stage, pausing to sniff dramatically as he looked all over the stage for the source of an odor. Then, in a strong voice, he would announce, “I smell smoke!” After a dramatic pause, he would look squarely into the faces of the audience and declare, “It is the smoke of burning draft cards, and it hangs over our nation like poisonous smog.” He would then make a case for the justness of a war to prevent the spread of communism, the importance of the rule of law, the duty of citizens to respect it, and the dangers posed by the draft card burners’ open defiance of it. He was fervently dedicated to this message. His speech won at the county and district levels, and he won second place at the state level, winning a college scholarship from the Legion that helped pay for his education at St. Joseph’s College in Philadelphia.

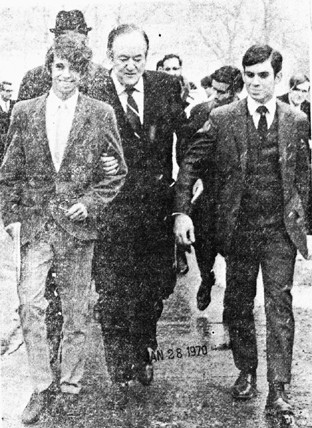

At St. Joseph’s College, Bob Williamson (left) was on the committee that invited prominent people to speak on campus, including the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and Vice President Hubert Humphrey, pictured here with Williamson, 1968. (Photo: Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, © Temple University Libraries)

By the time he said yes to Davidon’s invitation to consider burglarizing an FBI office, Williamson saw the war very differently. The change started when he wrote a paper on cluster bombs during his freshman year at college. In his research, he discovered that the manufacturer of these weapons, then being used in Vietnam, pointed out in corporate literature that the “advantage” of the cluster bombs was the widespread and diffused destruction they caused (including the killing of civilians). That assessment jolted Williamson and prompted him to start asking questions about the war. He had similar objections to the indiscriminate destructive power of napalm. When Martin Luther King spoke at St. Joseph’s in January 1968 and gave his reasons for opposing the Vietnam War—even in the face of criticism from his colleagues in the civil rights movement—Williamson took his message to heart.

A few months later, the night King was assassinated, Williamson was playing pool with some friends. One of them laughed and made a racist remark about King as they listened to the news that he had just been killed. Williamson burned with anger and sadness. He made a decision. “I realized that night I was getting to be a person whose principles were real important to me. I was at the point where I realized you had to take a stand for your principles.”

Now, after that meeting in the Bronx, he was committed to living his principles in ways that involved very serious risks. Instead of dressing up as Death, as part of an antiwar street theater group he had been performing with in the past year in Philadelphia, Williamson now prepared to raid draft boards. He took Grady’s warning seriously. He thought he would probably be caught the first time he broke into a draft board, but to his amazement, after raiding four draft boards and an FBI office, he still had not been arrested.

That luck changed at Camden. The expected finally happened on the parapet. He assumed his arrest in Camden also meant that his plan to have no plan for his future also would prove to have been wise. Feeling absolutely certain he would go to prison for years, he thought he would have plenty of time to think about the rest of his life.

Bob Williamson thought he would be convicted in Camden. Between his arrest and trial there, he visited New Mexico.

When it was clear the Camden trial would not get under way for at least a year, Williamson decided that after two years of continuously opposing the war and moving from one act of resistance to another, “It was probably time for me to have a little bit of fun before I went away to prison for forty years.” He went west. Some feminist friends he had lived with in Philadelphia were visiting Albuquerque. They liked the area and urged him to join them. That trip and the beautiful countryside it introduced him to transformed the geography and purpose of his life.

He had never been west of Ohio. Instead of going the fast interstate route, he purposely took a slow scenic route, watching the topography of the country change for two weeks as he drove. He camped in Oklahoma, where he saw a truly big sky for the first time. After he arrived in Albuquerque, he joined his friends near Taos. They left the campsite after a few days, and he spent a couple weeks alone there, soaking in nature.

For the first time in about three years, something besides the war grabbed and held his attention. “For a young guy who hadn’t been noticing nature for many years, if ever, the absorption with it now was healing,” he says. “It was cool in the morning. It warmed up throughout the day. And there was always a thunderstorm right before dusk. And then a magnificent sunset. They were orange and purple and red.…The sunsets really were magnificent.…The area was unspoiled and very beautiful. It was very quiet, and so it was good for me. I let my hair grow, and I enjoyed where I was.”

He continued to assume he would be going to prison and decided he should get ready for it. With that in mind, he hoped he could store memories of the peaceful and spectacularly beautiful New Mexico landscape so he would be able to retrieve and relive them for solace during the long days ahead in prison. He began what became a lifelong meditation practice. That too, he thought, would come in handy in prison. His time in that mountain meadow provided a rich respite.

In late 1972, the Camden trial beckoned and Williamson drove east. He became deeply absorbed in doing legal research and helping develop trial strategy. During the trial, he enjoyed cross-examining some of the witnesses, especially the FBI agent who had arrested him at Camden. Judge Fisher permitted him to use copies of some of the stolen Media files as the basis of questions he posed to at least one agent. He referred to the Media files again when he testified, claiming that reading the files and learning about the illegal activity of the FBI had convinced him to continue raiding draft boards. That’s why, he testified, he said yes when he was asked to participate in the Camden raid.

Williamson played a significant role in the defendants’ efforts to gain the judge’s trust and make him feel at ease with them. When the trial opened in February 1973, Williamson, as well as others, sensed that Judge Fisher was afraid this large group of defendants would be unruly. Memories were still fresh regarding the raucous nature of the 1969 Chicago Seven trial of people for allegedly conspiring to incite riots at the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago. Each new antiwar trial after that one was seen as a potential repeat of the Chicago trial with defiant defendants and defiant judges in the mold of the Chicago judge, Julius Hoffman. “I could understand his concern,” says Williamson of Judge Fisher’s rigidity in the early days of the trial. “There were so many of us. Most of us were representing ourselves. I had hair all the way down my back and often wore my dashiki. We were very different-looking—from each other and from the people who usually appeared in court.…Our goal was to tell our story, to explain why we had done what we had done, and to call on the jury, as an act of conscience, to make a statement about this war by finding us not guilty.…We had to get him to see that we had no intention of turning his courtroom into a ‘circus,’ ” a term Judge Fisher had used in a warning to the defendants right before the trial opened.

With that goal in mind, Williamson met with Judge Fisher shortly after the trial started and told him that he was going to do something tangible to reassure the judge that the defendants were sincere, reasonable people. He would be on a juice fast for the duration of the trial. It was a private gesture, not a publicity stunt, Williamson assured the judge. No one would know about it except the judge, the defendants, and the lawyers. He recalls that the judge’s “demeanor changed.…His first reaction was concern. He didn’t want me to hurt myself … he frequently asked me, in the hall or in chambers, how I was.”

Judge Fisher’s visible apprehension about the defendants melted fairly quickly. Each morning, as he took the bench, he scanned the faces of the defendants, their attorneys, and the prosecutors, establishing eye contact with many of them. His relaxed and expectant look suggested he was looking forward to whatever might happen in court that day.

Williamson maintained his secret juice fast throughout the three-month trial. Already very thin, he lost twenty pounds during the trial, but he remained healthy and energetic. He remembers savoring the celebratory spaghetti dinner, cooked by codefendant Peter Fordi, that broke his fast a few hours after the verdict was announced. Pasta may never have tasted so good.

Throughout the trial, Williamson felt he and his fellow defendants were creating an important record—not only about what they had done but also about the important role of resistance in American history and about the history of the Vietnam War and how that history had driven them to raid the Camden draft board. He was grateful the judge allowed them considerable leeway in giving testimony about their motivation. But despite how well the trial had gone, Williamson had no illusions about winning. “I don’t think any of us expected what happened.”

“When they said ‘not guilty’ after ‘not guilty’ after ‘not guilty,’ it was just the most unbelievable experience. I’ll never forget the exhilaration we felt, and the gratitude we all felt toward the jury, and their courage in returning those ‘not guilty’ verdicts. And it was also a very humbling experience.…Thoreau’s essay on civil disobedience was a guide for me, and part of the deal is that if you do the crime, you do the time. So, again, I expected to be arrested. I expected to go to prison.…I don’t think there was anyone, certainly at the defense table, who expected it to be an acquittal. We had no idea. None. I can’t stress that too much because it was just such an incredible shock to be found not guilty by these people.…It was deeply moving, it was very emotional.” He remembers hugging fellow defendants and being approached by the prosecutor, who shook his hand and wished him well. “I don’t remember what he said. I just remember what he did. He was very gracious.”

Then, several minutes later, one of the FBI agents who had been involved in the case from the beginning “came up to me in the men’s room and congratulated me and wished me luck. It was as though he was saying, ‘It’s okay now. We’re going to let this go. We’re going to move on now.’…I didn’t feel triumphant. That wasn’t really the feeling. It was more like grateful.”

Even in his toughest times years later, Williamson was always able to evoke again the emotion of that moment when he suddenly realized that the jury had acquitted him and all of the defendants. In his living room many years later in Albuquerque, as he recalls the moment when verdicts were announced, his eyes fill with tears, as they did that day in Camden. He still finds it hard to believe that the jury voted as it did. “It was really something.…It was an unbelievable thrill.”

SOON AFTER being acquitted at Camden, Williamson was faced with a new question: Now what? “The expected ending—that I would go to prison—didn’t happen. I was free. The war by then was clearly coming to an end.…Watergate was well under way. And I had no idea who I was. I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life. My assumption had been that I would go to prison, that I would spend however many years in prison and those years would give me ample time to reflect on the next step. Instead, the government wasn’t going to be providing me with room and board, and I needed to find some way to more or less take care of myself.”

About three months after the trial ended, Williamson had a deep realization that he needed to “get away from all these people. As much as I loved them, as much as we’d all been through together.…My friends, almost without exception, were like, ‘It’s on to the next battle.’ But I wanted the war to be over.”

In Philadelphia at that time, he recalls, “What you do all day is you’re figuring out … how to stop the government.…It’s nonstop. I mean, it just never ends. It’s one meeting after another.…As spirited as those discussions were, there was also an element of groupthink. I felt I would lose myself if I stayed there any longer. And, fortunately, I had this place to come to.”

“This place” was New Mexico. The beautiful mountains, deserts, and glorious sunsets lured him west again. Life had been good there in the months between the arraignment and trial. As soon as Williamson had enough money, “I decided I was going to New Mexico. I came out here and got a job driving a school bus part-time, lived in a cabin up in the mountains, chopping wood, carrying my own water … and I lived alone for, oh, a good year and a half.”

He felt content at first in New Mexico. Years later, he said New Mexico rescued him all those years ago. If he had not moved west, Williamson feels he would have become frozen in time. But there also were very difficult times during his earliest years in New Mexico. He spent a lot of time meditating. He smoked a lot of dope. He had some friends. But he didn’t have a purpose. And he was very lonely.

When he read years later about how NASA prepared astronauts for life after traveling in space, Williamson wished the resistance community could have done what NASA did. As astronauts were being trained for a trip to outer space, they were also required to have a second goal, one they wanted to achieve after they returned from their dramatic voyage in space. NASA learned, says Williamson, “that when people have set their sights on something for a long period of time and … devoted themselves to achieving it, and when that goal has been reached and is over with, a lot of people … then go into a deep depression because they don’t know who they are without the definition they got from the original goal.

“Well, that’s what happened to me. My entire self-image was that of an antiwar crusader, an antiwar resister.”

Williamson found that most of the people he met in Albuquerque didn’t seem very interested in his resistance past, and they weren’t as consumed with politics as he had been. He had mixed feelings about this reaction. On the one hand, he had just been through several extremely eventful and dramatic years. From his perspective, it was, if nothing else, quite a story. But on the other hand, there was something very refreshing about living among people who were more interested in who you were now than in who you used to be, and more interested in your character than in your political views. Eventually, he reached the point where he rarely talked about “the old days.”

It was difficult to decide what he was going to do with his life. He no longer could accept the conclusions of many of his old friends in the resistance movement. “Since the world is unfair, they thought we should be in rebellion against ‘the system’ and not cooperate with it in any way, live our lives blaming the system, speaking out against it at every opportunity and being in resistance to everything it stands for.” Williamson no longer was willing to live that way.

As he struggled with his first steps toward a new purpose in life, he nearly hit bottom once when a relationship that meant a great deal to him didn’t work out. He decided to leave New Mexico. “I wanted to get as far away from Albuquerque as I could get and still be as far away from Philadelphia and New Jersey as I could get.” He jumped at the chance to drive to Miami when a friend wanted to relocate there.

It was the winter of 1974. Williamson had no money and no food by the time he arrived in Miami, and he pawned his guitar for cash. He was living in his Volkswagen, trying unsuccessfully to find a job. One night, he got “an unbelievably bad toothache, the worst pain I had ever felt.” Sitting in his car, he started feeling very sorry for himself. Reflecting back on his life to that point, he remembers complaining to God: “I’m a good person. I risked my freedom to try to stop a war and make my country a better, a more just place. Here I am, and I’m alone, I don’t know anyone here, I’m broke, I’m hungry, I’m in pain, and no one cares.”

As he sank deeper into his misery that night, he suddenly had a powerful insight, which he describes as a spiritual experience. He realized that he alone was responsible for his situation. He had chosen to be alone in a strange city. He had no money because he hadn’t earned any. No one else was responsible for his situation; he alone was. If it was going to change, it would be up to him to change it.

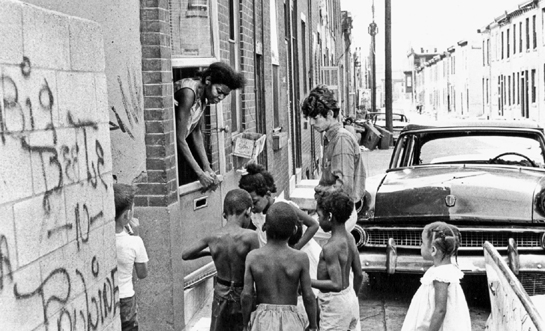

While he was a college student, Williamson and other students who lived in North Philadelphia did volunteer work for an organization that helped renters negotiate with landlords to repair their apartments.

Almost forty years after that night, he still had trouble putting the experience of that insight into words. “I wasn’t sitting there, calmly and rationally thinking through my dilemma and devising a solution. I was in excruciating pain, sobbing, one of the absolute lowest emotional points in my life. And suddenly, I was filled with this awareness of an idea, and everything sort of stopped for a minute.

“I have tried to put the realization into words, but my words don’t really do it justice. Since that night, I have had my share of bad days, but on that night something fundamentally changed in me. Since that night, there have been times when I wanted to feel sorry for myself, but I just couldn’t sustain the self-pity anymore. From that night on, at some level, I knew better.”

This insight was followed by the quick realization that his toothache had gone away completely. The next morning, Williamson walked into a small newspaper and got a job. That soon led to a job at a larger newspaper in Miami Beach, where he developed skills as a production manager, skills he used later when he returned to Albuquerque and started a graphic arts business.

During Williamson’s search for new meaning in his life, he says he got tremendous value from participating in what was called “est”—Erhard Seminar Training, intensive seminars created by Werner Erhard in the 1970s and attended by thousands of people. Williamson found est particularly helpful “because it emphasized personal responsibility, which it defined as neither blame nor credit, but rather a willingness to operate from the assumption that I am responsible for the way I experience life. This was not presented as a truth or a dogma. It was simply a way of looking at life that I found empowering. I realized that if I lived my life from the point of view that I was truly the author of my own life, I might end up being right or wrong about that, but in the meantime, I would have been far more resourceful than if I had acted as if the outcomes in my life were determined by outside forces.…As a result of est, I understood and accepted myself—warts and all—far more than I had up to that point in my life. I also found that it became possible for me to be far less judgmental of others as well—particularly people in public life whom I had never met and had no actual personal experience of.”

For the past twenty-five years, Williamson has worked as a business coach, holding online meetings and seminars to help clients achieve personal and business goals. He does some pro bono coaching and has served on nonprofit boards in his community.

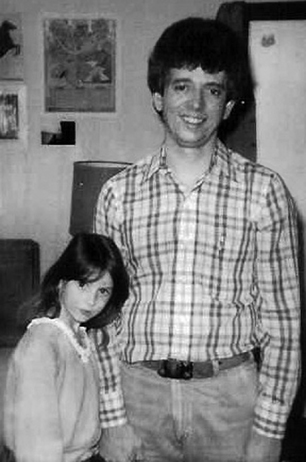

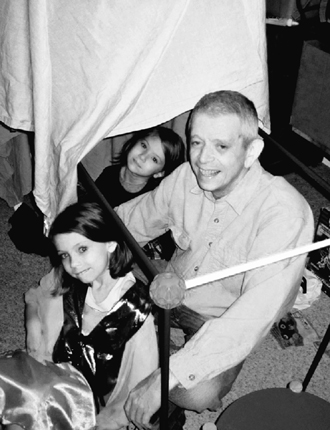

Bob Williamson with his daughter, Jessica, age six, in 1984.

He has been married and divorced twice. The graphic arts business he started in 1975 eventually failed after twelve years, leaving him $80,000 in debt. As a matter of principle, he refused to go into bankruptcy and instead scrimped and saved for years until he paid all his debts. He says, “I think I have had my share of struggles in life, and made more than my share of mistakes. During the most difficult times, I have even experienced depression and near despair. I am not what most people would call a wealthy man, but my needs are met and I have been able to give something back. I have a passion for my work and it gives me great satisfaction. So while my life has not been a bed of roses, I am grateful for an underlying sense of optimism and good humor which has always carried me through the tough times.”

A tremendous source of his happiness is being part of the lives of his daughter, Jessica, born in 1978, his son-in-law, Mike, and his two granddaughters—Aelea, born in 2004, and Raven, born in 2008.

As he started to erase his old identity as a resister, Williamson says, “it was clear to me that what I thought about the way the world should work really didn’t make much difference to the world, and that the world was a lot bigger than I was.…I was going to have to figure out some kind of way to make peace with it. And that,” he says, “was the beginning of an odyssey for me which was about the ending of my focusing on the world and trying to fix the world’s problems and the beginning of my turning that vision inward to try and discover whether I was the best person I could be.

“I stopped blaming my parents, and I stopped blaming society, and I stopped blaming the economic system and I stopped blaming people’s indifference and I stopped blaming racism and sexism and everything else for the way things were, and I started thinking more and more … about who I was, and whether I was becoming everything that I could be. That began to be the question around which I framed my life.”

During this evolution, he apologized to his parents and siblings for the anguish his resistance against the war had caused them. From the time he left college to live in a poor neighborhood in North Philadelphia, through his years as an antiwar activist, his parents were repeatedly shocked by his actions. When he was arrested in Camden, they were mortified, a reaction that was deepened when an official in their small community wrote a letter that was published in the local newspaper stating how ashamed he was that someone from Runnemede was involved with people who broke into draft boards. With sadness, he recalls, “My parents felt shamed in their own community.”

Williamson moved from being an intensely engaged political activist to becoming apolitical and then later a conservative with libertarian leanings. He worked behind the scenes in 1982 as a speechwriter for the Republican candidate for governor of New Mexico. He laughs as he suggests, undoubtedly correctly, that he is probably the only Media burglar who voted not only once but twice for both Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush. The writings of conservative economists Friedrich Hayek and Thomas Sowell have strongly influenced his thinking in recent years.

There was a time, Williamson says, when he was tempted to enter politics himself, but he cured himself of that delusion by considering the spectacle of trying to explain to voters how someone who opposed the Vietnam War by breaking into draft boards—and the FBI—could have become a conservative. “Virtually every voter would be able to find something completely distasteful about me in either my past or my present.”

AS WILLIAMSON REBUILT his life, he seldom thought of his acts of resistance—including the Media burglary. At times he viewed them as having little significance beyond whatever their personal meaning was to each individual burglar. With the passage of time, the memories and the personal meaning of his own resistance became a smaller part of the “odyssey I’ve been through since then.”

One evening, about fifteen years after the burglary, he was perusing the Albuquerque television listings and noticed that one station would be broadcasting a documentary on the FBI. His reaction was a little like the interest stirred by reading a news item about an old high school friend one hasn’t seen in many years. He decided to watch it.

As the program started, the narrator announced that in 1971 a group of people, who were never found, burglarized the small FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania. Williamson was puzzled. He wondered why the reporter was talking about “our burglary.” The reporter went on to say that much of what is known about how the FBI operated under J. Edgar Hoover is a result of the Media burglary—that the burglary was seminal in the passage of changes to the Freedom of Information Act and various reforms in the FBI.

“Well, I remember being dumbstruck that somebody apparently thought that our little action was that important.…Until that moment, I never thought it had any long-range impact.”

By the time the program ended, he was seeing the Media burglary in a somewhat different light. “The thing that impressed me about it was that here I am, just some guy, and my friends and I pulled this thing off. And it had an impact.

“I still get chill bumps when I realize that the Media burglary started a long chain of events that caused reforms.…And we didn’t even know what we were doing. We had no idea whether our risk would result in anything.…It’s very gratifying to know that people … think that we performed a service to our country. That’s what we intended to do. I know our hearts were pure in that regard.”

His gratification that the Media action produced some positive results in terms of more openness in the FBI in particular and government in general has also been tempered by his sobering view that the law of unintended consequences works both ways. Williamson thinks the revelations that came out as a result of the burglary probably also contributed to the increasing cynicism and distrust Americans felt then—and continue to feel now—about their government. He thinks much of that distrust is probably deserved. But he also thinks that, in some ways, it has made it more difficult for leaders at every level of government to do what they think is right. “Four American presidents believed the Vietnam War had to be pursued. They may have been wrong about that on any number of levels, but I have come to respect the fact that they had more information than I did, and I have come to believe they all did what they thought was right. That does not change the fact that I also did what I thought was right, and so did all of the other people I worked with back then … but it tempers it with a big dose of humility.”

At the center of Williamson’s life in Albuquerque are his daughter, Jessica; her husband, Mike; and their two children, Aelea (foreground) and Raven, seen here in January 2012 with Williamson.

Since the night Williamson shined a taped flashlight’s narrow beam on open FBI file cabinet drawers, guiding fellow burglars in the dark, he has become a much more conservative person. Nevertheless, he views his radical act of burglarizing an FBI office as a patriotic act that gave him a sense of accomplishment then and now, notwithstanding his concerns about unintended consequences. “That was an exciting time,” he says, “and it was one of the times in my life when I felt most alive. I don’t regret it.”

While he would not presume to offer advice to anyone now considering action as extreme as what he participated in at Media, he hopes such people would give it long and careful thought. “That burglary is an example of what someone can do, or try to do, as a citizen. But when you take an action like that, you own the consequences. I was not prosecuted for the break-in, or for distributing those FBI files to the media. Nevertheless, the consequences for me—personally, emotionally, spiritually—have been fairly significant. I know that at the age of twenty-two, I acted with a clear conscience. I also know that I could not possibly have foreseen the full range of effects of my actions then. Over the last forty-plus years, as I have grown older, thinking about this has made me more careful about how my actions are likely to affect others. Still, in spite of that, I think I can make a pretty good case that, on balance, the Media burglary produced more good than harm.”