IT SHOULD BE OBVIOUS THAT JOB descriptions, performance appraisals, and salary administration all fit together in one overall plan. They are designed to provide accurate descriptions of what people do, give fair evaluations of their performance, and pay them a salary that is reasonable for their efforts. All these factors must bear a proper relationship to one another and make a contribution to the organization’s overall goals.

If you have a job evaluation program, you probably also have salary ranges for each position in the organization. As a manager, you work within that scale.

It makes sense to have a minimum and a maximum salary for each position. You can’t allow a situation to develop in which an individual could stay on the same job for years and receive a salary out of all proportion to what the task is worth. It’s important to make certain that long-term employees are aware of this situation, especially as they get close to the salary cap on the job. For most well-qualified people this is not a problem, because they’ll usually be promoted to another job with a larger salary range. However, in your managerial career, you will encounter long-term employees who remain in the same jobs. Perhaps they don’t want to be promoted. Perhaps they are at their level of competence and cannot handle the next position up the ladder.

These people need to know that there is a limit to what the job is worth to the organization. You have to tell these individuals that once they are at the maximum, the only way they can receive more money is if the top end of the salary range for their type of position is increased. This may happen, for example, through a cost-of-living increase that raises the ranges on all jobs by a certain percent. Should that occur, you would have a little room for awarding salary increases.

Nonetheless, long-term employees who stay in the same job for an extended period of time and who are at maximum salary level need to have continued incentives. They are capable and should be kept on the job. Many companies have solved this problem by instituting annual financial awards related to years of service. Another approach is an annual discretionary performance bonus.

The salary administration program for all other employees usually includes a salary recommendation within a range of pay increases, based on the kind of performance appraisal the employee has received. Since the two procedures have such an impact on each other, some companies separate the salary recommendation from the performance appraisal rating. In that way, a manager’s idea of what a salary increase ought to be is not allowed to determine the performance appraisal given. If as manager you make both determinations at the same time, you’ll be tempted to take the answer you want and work backward to justify it. It remains difficult to separate salary consideration from the performance appraisal, but completing the procedures several weeks or months apart may help.

Let’s assume your company does have salary ranges for each job and there is some limitation on what you can recommend. No doubt the salary ranges overlap. For example, a veteran employee on a lower-level job could be paid more than a newer employee on a higher-level job. An outstanding performer at one level could be paid more than a mediocre worker one level up.

EQUITY

As the manager, you’re concerned with equity. You should review the salaries of all the people who report to you. You might begin by listing all the jobs in your department, from top to bottom. You might then write the monthly salary next to each name. Based on what you know about the job performances, do the salaries look reasonable? Is there any salary that looks out of line?

Another method you can use is to rank the jobs in the order of importance to the department, as you perceive the situation. How does that compare with top management’s evaluation of the importance of the jobs? If there are differences you can’t reconcile or accept, then it would be wise to schedule a meeting with your supervisor to see what can be done about it.

In this matter of rankings, appraisals, and salaries, it is important once again to emphasize a critical point. As mentioned in Chapter 29, recognize—and be willing to admit to yourself—that you like some employees more than others. You’re fooling yourself if you think you like them all equally. Certain personality types are more agreeable to you than others. It is vital that you keep these personality preferences from unduly influencing the decisions you make about appraisals, salaries, and promotions.

In recommending a salary increase for several employees, you’ll have some tricky decisions to make. If the company makes all its salary adjustments at the same time each year, then it’s fairly easy to compare one recommendation against another. You can make all your decisions at one time and see how they stack up with one another. But if salary decisions occur throughout the year—for example, if they are tied to the worker’s employment anniversary—it’s more difficult to have all the decisions spread out in front of you.

Although maintaining equity in this type of situation is difficult, it is possible if you keep adequate records. Retain copies of all your job descriptions, performance appraisals, and salary recommendations. Some companies encourage supervisors not to keep such records and to depend on the human resources department’s records. Maintaining your own set is worth the effort, however; you’ll then have the records when you want them. Keep these records in a file that is locked or password protected, and do not allow any employee access to the file—not even a secretary or assistant who works closely with you. This kind of information has a way of getting shared if it becomes known.

THE SALARY RECOMMENDATION

In making a salary recommendation, be as sure as you possibly can that it’s a reasonable amount. It should be neither too low nor too high and at the same time it must fit within the framework of the performance the employee gives the company. An increase that is too high, for example, could create an “encore” problem. Anything less than the same amount offered the next time around may be considered an insult or an indication of inferior performance by the employee. However, an unusually large increase coming at the time of a promotion doesn’t run that same encore danger because it can be tied to a specific, non-recurring event. In that case, you must explain to the employee why the increase is so large and why it doesn’t create a precedent for future increases.

Since a small increase can be considered an insult, you’d perhaps do better to recommend no increase at all rather than a pittance. Sometimes a small increase is a dodge, and is given because the supervisor lacks the courage to recommend no increase. But this only postpones the inevitable reckoning; you are better off confronting the situation immediately and honestly.

When considering the amount of the raise, it’s essential that you not allow the employee’s need to be an important factor. This may seem inhumane, but consider these points. If you based salary increases on need, the employee in the most desperate state of need would be the highest paid. If that person were also the best performer, you’d have no problem. But what if the employee’s performance was merely average?

This does not mean you should be insensitive to the personal challenges of your team members. There are valuable nonmonetary things you can offer to assist them based on their circumstances. It may be that an employee has become a caretaker for a parent or is having challenges with childcare. Allowing him to telecommute or participate in meetings through teleconferencing may significantly assist him. Flexible work hours are another nonmonetary means you can consider that may be very helpful to the team member while not compromising the integrity of your compensation structure.

The common thread that must run through salary administration is merit. Basing your salary recommendations on who has been with the company the longest, who has the greatest number of children, or whose mother is ill moves you away from your responsibilities as a salary administrator and puts you in the charity business. If you have direct reports with financial problems, you can be helpful as a friend, a good listener, or a source of information about where to go for professional assistance, but you can’t use the salary dollars you’re charged with as a method of solving the social problems of your direct reports.

When you’re making a salary adjustment for an employee who’s having difficulty, there is a great temptation to add a few more dollars than you would otherwise. You must resist that temptation and base your decision strictly on the performance of the individual employee.

TALENT MANAGEMENT

Because part of a manager’s job is anticipating challenges and requirements before they arrive you need to be thinking ahead regarding the skills and capabilities your people need. Start by asking yourself how the tasks your team needs to accomplish will be different in the future. What do you see ahead that will cause your team’s mission to change? If you are not sure, talk to your supervisor and some of your peers. Ask them, “What changes do you see coming that will cause my team’s role to evolve?”

An example could be an increased capability to do more of your tasks online. There may be possible acquisitions that could cause your team to have to do things differently. An example could be future dealings with colleagues or customers who do not speak the same native language as your team.

Another issue could be the natural advancement of some of your team members. Some of your people may be obvious candidates for promotion or near retirement. You need to be ready for either so your team is not suddenly much less capable because you did not plan ahead.

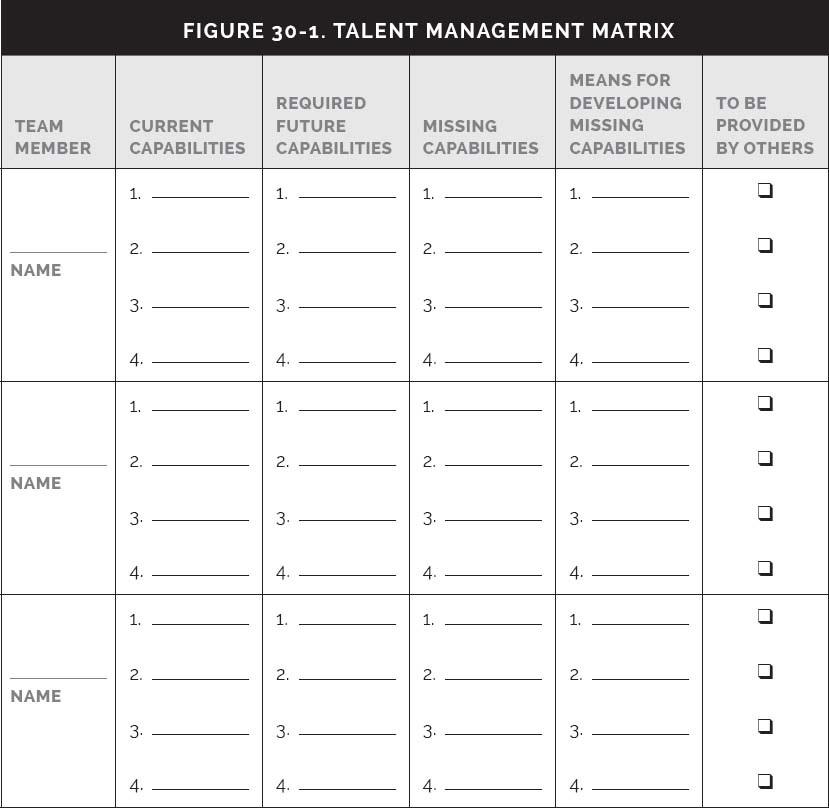

Planning ahead means looking at each of your team member’s capabilities with future challenges or personnel changes in mind. This process is not as challenging as you may think. The Talent Management Matrix, shown again here in Figure 30-1 will make it straightforward.

Here is the process:

1. First identify what time horizon you are planning for. That is the projected date near the top of the matrix. It may only be six months from now or as far as two years out. Planning more than two years ahead is tough because there are so many variables.

2. List each member of your team in the first column.

3. In the second column titled Current Capabilities list that person’s primary capabilities that they use to do their job.

4. This step is the one that requires the most thought. With the responsibilities you see in the future for your team as influenced by changes in the organization or personnel list the capabilities they will need to have in the future in the column titled Required Future Capabilities. Some of these will likely be the same as the capabilities they currently need to be successful. It may be that for some of your team members nothing will change. That is fine. Determining that is valuable. For others there may be a need for them to add capabilities they do not currently have. List those.

5. Now look at the capabilities that each team member will need that they currently do not have. Those go into the column titled Missing Capabilities.

6. Next you need to determine how the team member is going to gain those capabilities. Examples may be internal training, external training, online courses, shadowing someone who has that capability, on-the-job training, cross training or whatever method you see as appropriate. These go into the column titled Means for Developing Missing Capabilities.

7. Your final task in this assessment is to determine if it is not realistic for a certain team member to acquire any of the capabilities that will be needed. If that is the case, put a checkmark in the final column indicating that capability will need to be provided by someone else—either another team member, someone new, or an external resource.

Here is an example. Let’s say that your organization is moving into a market that will require some on your team to have the ability to communicate in a language they do not currently speak. This will then be one of the items listed in both the Required Future Capabilities column and the Missing Capabilities column.

The first obvious thing to do is determine if anyone on your team already has that ability. Assuming they do not you need to determine how this talent is going to be acquired. It may be that an online language training course is appropriate. Or evening language classes if available may be appropriate. Part of the training process may be having the person travel to a setting where the language they need to learn is spoken.

Alternatively, you may determine that there are other ways to address this need. Let’s say you determine that all that is needed is the occasional translation of some forms. That is something that you can pay an outside source to handle, or perhaps there is someone in your organization who is not on your team who can to that. It may be that only occasional translation is needed and an outside real-time translation service is available.

The important part is that you are planning ahead so you will not be caught by surprise. That is your job as a manager. The second part is that a thoughtfully completed Talent Management Matrix is a powerful tool when working with your supervisor. Think about how much better it makes your case for adding a member to your team if you place it in front of your supervisor to explain your reasoning.