The majority of the IPB process needs to be done ahead of time. You simply will not have time during combat to establish any database or to perform an in-depth analysis of the enemy, weather, or terrain. To successfully plan and execute the R&S operation, you must have this detailed analysis. The IPB process has five components:

Refer to FM 34-130, Intelligence Preparation of the Battlefield, for detailed information on IPB.

Battlefield Area Evaluation

BAE is the first step of the IPB process. Begin your analysis by figuring out what part of the battlefield should be of interest to you and your commander. The end result of this step is the identification of the area of interest (AI): that part of the battlefield which contains significant terrain features or enemy units and weapon systems that may affect your unit’s near or future battle.

BAE is a crucial step in the IPB process because it focuses your analytical efforts on a finite piece of the battlefield. By extension, it will also provide geographic limits to your R&S and collection efforts.

The commander bases the unit’s AI on many things. It is normally an expansion of your unit’s area of operations (AO). It should be large enough to provide answers to the commander’s PIR, yet small enough to prevent your analytical efforts from becoming unfocused. Determining the AI depends on the unit mission and threat capabilities. For example, if your unit is to attack, your AI should extend across your LD/LC up to and surrounding your intermediate and subsequent objectives.

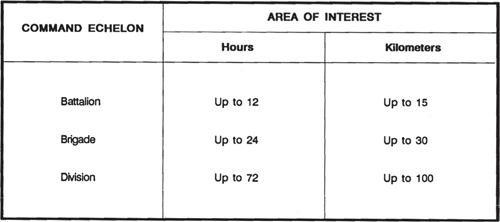

If the mission is to defend, the AI should extend far enough to include any possible units that might reinforce against you. You can base your AI considerations in terms of time and on how fast you or the enemy moves. Figure 2-2 lists general distance guidelines in hours and kilometers; use this to determine your unit’s AI.

Figure 2-2. General distance guidelines.

Considerations for your AI should be expressed in terms of distance, based on:

For example, a battalion commander fighting an attacking enemy using Soviet tactics is normally interested in 1st- and 2nd-echelon battalions of 1st-echelon regiments.

Doctrinally, these units would normally be from 1 to 15 kilometers from our FLOT. Therefore, the AI should extend forward at least 15 kilometers.

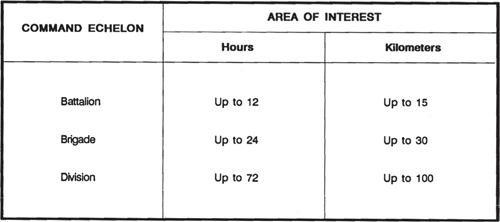

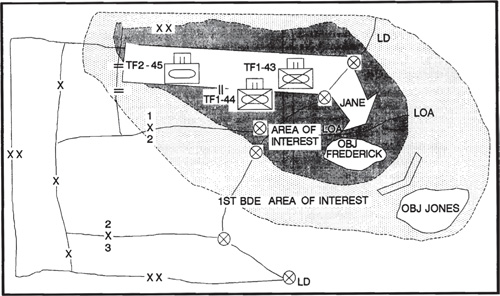

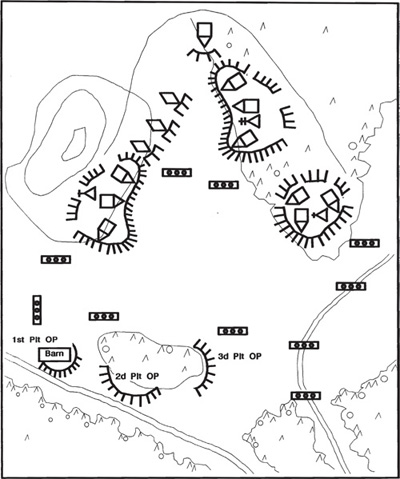

You must determine your AI during mission analysis. Your commander and S3 play a big part in formulating the AI. They tell you what their intelligence concerns are. Like PIR, your unit’s AI must be the commanders and must be sent to higher headquarters. Figures 2-3 and 2-4 show examples of AIs for defensive and offensive missions. Figure 2-5 shows both defensive and offensive. It will help in determining your unit’s AI.

Figure 2-3. Area of interest in the defense.

Figure 2-4. Area of interest in the offense.

Figure 2-5. Defensive and offensive areas of interest.

Terrain Analysis and Weather Analysis

The next two steps in the IPB process are terrain and weather analyses. Essentially, these are detailed studies of how the terrain and weather will affect both friendly and enemy operations. Specifically, terrain and weather will dictate how effective R&S assets will be, and where they should go to be most effective. Your knowledge of terrain and weather will allow you to anticipate effects on friendly and enemy R&S systems and operations.

Terrain analysis and weather analysis should start as soon as you have determined your AI. Do not wait until you deploy to start your analysis! The more prepared you are, the better the R&S plan will be. Figures 2-6 and 2-7 show specific uses and effects for terrain and weather analyses.

Figure 2-6. Special uses and effects of terrain.

Figure 2-7. Effects of environment on R&S.

Threat Evaluation

Once you have analyzed terrain and weather, begin a thorough study of enemy:

This study results in threat evaluation, the fourth step in the IPB process. During this step:

Doctrinal templates are important because they show how the enemy doctrinally attacks or defends in various situations. Knowing how the enemy defends will tell you what you ought to look for in order to confirm that they are, in fact, defending.

Knowing how the enemy employs reconnaissance in the attack will help you target them, allowing you to destroy or neutralize those assets. It also helps you determine which of those assets are most important to the enemy’s reconnaissance effort.

Figures 2-8 and 2-9 are examples of doctrinal templates you might use specifically for R&S planning. Whenever you use doctrinal templates, you must temper them with some reality. For example: a Soviet regimental attack template has set doctrinal sector widths. It serves no purpose to place this over a map where a battalion falls outside an AA. There is enough leeway, even in Soviet doctrine, to conform to terrain limitations; when using the template you must make those same allowances.

A careful study of threat doctrine tells how fast they will attack in various situations. This information will become very important later on. For right now, remember during threat evaluation that you determine enemy doctrinal rates of advance. Figure 2-10 is a table of enemy rates of advance for specific situations and terrain.

Finally, knowing how the threat uses weapon systems and units gives you an appreciation of which are most important to the enemy commander in a particular situation. These important weapon systems and units are called high value targets (HVTs). They are the starting point for the target value analysis process. Target acquisition is an important aspect of R&S and CR. Target value analysis will play a big role in your R&S planning.

Threat Integration

Remember, the four IPB steps should be started before deployment. They ought to be part of your day-by-day intelligence operations. You are now at the point where you can pull together what you have developed about the enemy, weather, and terrain and apply it to a specific battlefield situation.

This step is threat integration. You will discover you can also perform some threat integration functions ahead of time. The first such function is to develop a series of situation templates depicting how you think the enemy will deploy assets.

Situation Template

The situation template takes what is on the doctrinal template and integrates what you know about weather and terrain. The situation templates will show how an enemy unit might modify its doctrine and tactics because of the effects of weather and terrain.

Figure 2-8. Doctrinal template of an MRC (reinforced) strong point.

Figure 2-9. Offensive doctrinal tempelate.

Figure 2-10. Threat rates of advance.

Figure 2-11 is an example of one situation template. It is important to understand that you should develop as many situation templates as there are enemy COAs. This allows you to thoroughly examine what options the enemy has for each COA.

For example, you may discover enemy forces have to use specific bridges, road intersections, or mobility corridors (MCs) for a specific

Figure 2-11. Situation template.

COA. Or you may discover that the terrain offers the enemy several choices to attack. Or you may determine the terrain offers a limited number of suitable enemy defensive positions. And you may learn that the terrain only provides a limited number of concealed routes for enemy reconnaissance to enter your sector.

The bridges, road intersections, and possible defensive positions you have identified become NAI. Focus your attention on these NAI because it is there you expect something to happen. What you see or fail to see at your NAI will confirm whether or not the enemy is doing what you expected them to do, as projected on the situation template. NAI do several things for you. They:

Remember, one of the things you did during threat evaluation was to determine enemy rates of advance. You now put this knowledge to work by developing time phase lines (TPLs). Think of TPLs as snapshots of an enemy or a friendly frontline trace. A series of TPLs would portray friendly or enemy movement over a period of time.

Event Template

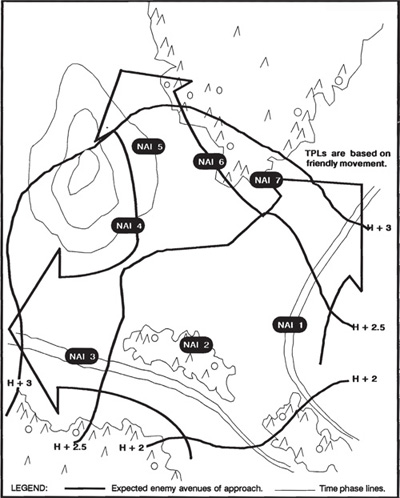

If you combine NAI with TPLs, you will be able to show approximately when and where you would expect to see enemy critical events occur. This is basically what the event template does. Figure 2-12 is a sample event template.

The event template allows you to:

Of all IPB products, the event template is the most important product for the R&S effort. As you will see, the event template is also the basis for the decision support template (DST).

In many situations you might find it helpful to calculate how long an enemy unit would take to move from one NAI to another. Normally, your

Figure 2-12. Event template.

calculations will be based on opposition and doctrinal rates of advance. Situational aspects such as weather, terrain, and your previous hindering actions are also factored in.

Comparing actual movement rates with your calculations will tell you whether the enemy is moving slower or faster than expected. It will also help you predict how long it will actually take the enemy to reach a certain point (your FEBA, for example).

Event Analysis Matrix

The event analysis matrix is a tool used along with the event template to analyze specific events. Figure 2-13 shows examples of event analysis matrixes.

Basically, you calculate the not earlier than (NET) and the not later than (NLT) times lead elements of a unit will arrive at an NAI. Determine the distance between NAI and multiply the distance by the expected rate of advance.

For example, suppose the distance between NAI 1 and NAI 2 is 2.5 kilometers. Suppose also, for the sake of this example, that the enemy expected rate of advance is 6 kilometers per hour, or 1 kilometer every 10 minutes. Use this formula to calculate time:

distance/rate = time

2.5 km ÷ .1 km (1 km every 10 minutes) = 25 minutes. Therefore, it takes the unit 25 minutes to travel from NAI 1 to NAI 2.

Decision Support Template

The final IPB product is the DST. The purpose of the DST is to synchronize all battlefield operating systems (BOS) to the commander’s best advantage. The DST consists of target areas of interest (TAI), decision points or lines, TPLs, and a synchronization matrix. Figure 2-14 shows a DST.

There are many important things you should know about the DST. First, the DST is a total staff product, not something the S2 makes in isolation. Although you may begin the process of developing the DST, the S3 and the commander drive the development.

Second, the DST is a product of war gaming. Together with the rest of the staff, you develop friendly COAs which consider what you envision the enemy doing. As a result of this action, reaction, and counteraction war game, you identify actions and decisions that may occur during the battle.

Third, the R&S plan must support the DST.

Figure 2-13. Event analysis matrixes.

Fourth, you can use the DST, as well as the general battle plan, to synchronize the R&S effort.

As a result of the war-gaming process, the staff identifies HPTs—those enemy weapon systems and units that must be acquired and successfully attacked for the success of the friendly commander’s mission.

Figure 2-14. Decision support template.

The staff identifies HPTs from the list of HVTs you developed during threat evaluation. (See FM 6-20-10, TTP for the Targeting Process.)

Once the staff has decided on HPTs, it begins to identify where on the battlefield it can best interdict them. These interdicting sites are labelled TAI. The next step is for the staff to decide how best to interdict the enemy at a particular TAI. The method of interdiction will determine the location of decision points or lines.

Decision points or lines are a time and a place on the battlefield which represent the last chance your commander has to decide to use a specific system for a particular TAI. Once the enemy or friendly forces pass the decision point, the ability to use that system is lost. Logically, you should monitor decision points to detect if and when enemy units enter and to confirm enemy rates of movement.

This logical relationship shows that NAI (such as your event template) must support your decision points. There is a relationship between NAI and TAI as well. If battle damage assessment of a particular TAI is important, your event template (and your R&S plan) must support that TAI.