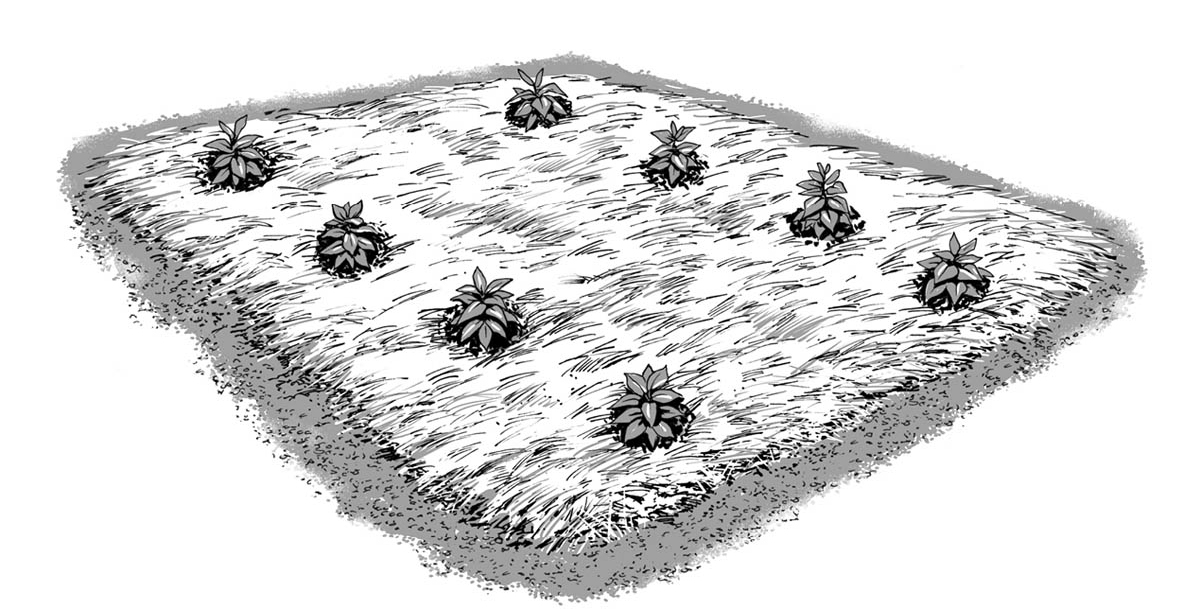

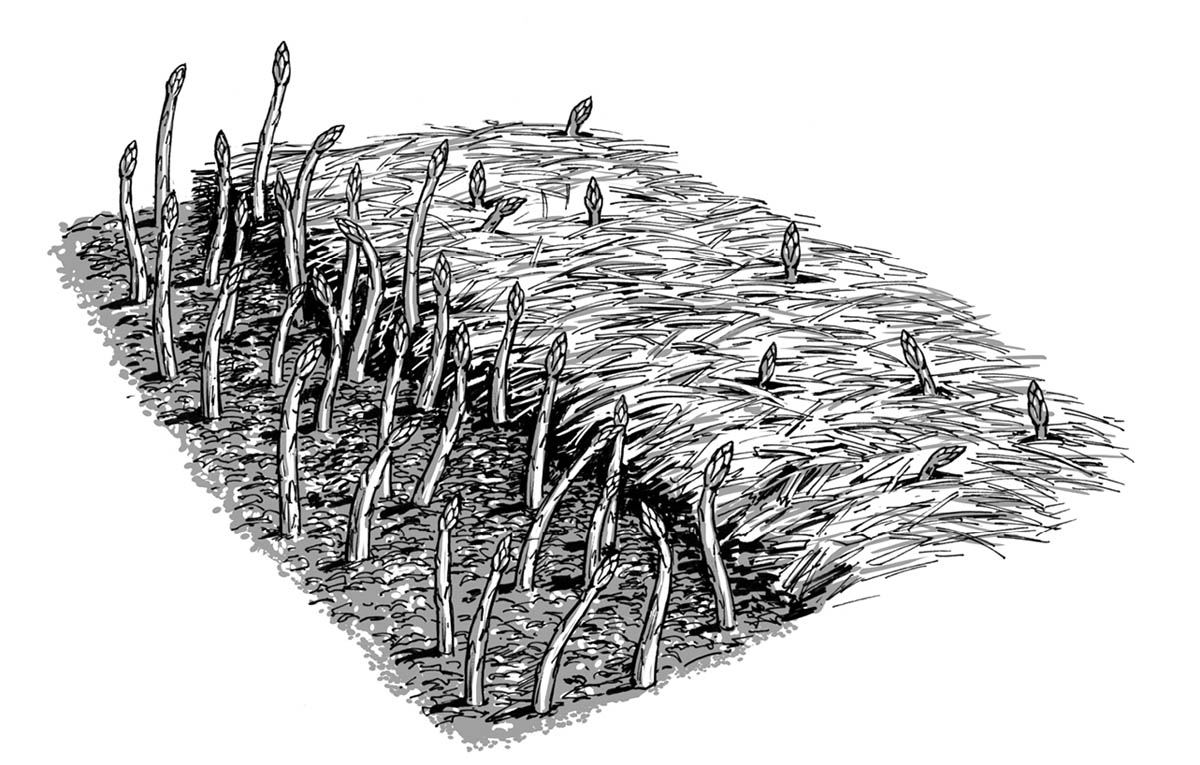

Mulching with straw. Place thick layers from straw bales between rows in the vegetable garden to keep weeds under control and to keep plants clean.

In addition to knowing what to use as mulch, the savvy gardener learns how much, where, and when to mulch. Specific recommendations for mulching ornamental plants, vegetables, and fruits follow a little later in this book. For now let’s start with some general tips for getting the most out of your mulch.

Keep this mulching primer handy. Whether you are laying plastic for the first time or refreshing last season’s wood chips, the following considerations will help you successfully plan and carry out your mulching strategy.

Don’t try to stretch your mulch too far. Using too little mulch is like trying to paint with a dry brush. The end result isn’t worth much. Try to figure out beforehand how much mulch you are going to need. A 100-square-foot garden will need 11⁄4 to 11⁄2 cubic yards of shredded bark, leaf mold, or gravel to make a mulch layer 4 inches deep. That’s eight to nine wheelbarrows full of mulch. It’s always good to have extra mulch on hand to replace any that’s washed away or decayed, or to cover a newly spaded area. Almost invariably you will end up using more mulch than you thought you would. And you can always stockpile what you do not use.

The thickness of your mulch depends on the material you use. Usually the finer the material, the thinner the mulch layer. Mulch depth can vary from 1 inch for small particles like sawdust to 12 inches for bulky stuff like coarse straw.

Remember that plant roots need to breathe. Air is one of the vital elements in any good soil structure: 50 percent air and 50 percent solid material is a healthy mix. Soil that is too compact has little or no air. One benefit of mulching is that it prevents soil compaction.

Don’t mulch so deeply that you suffocate your plants’ roots under too much material. Let your soil breathe. A thick mat of wet leaves that bond together and cake can be impenetrable. Fine mulches, unless they are applied sparingly, can compact and prevent air penetration, too.

Replace old mulch that’s become decayed and compacted. Mulching promotes shallow root growth. Because the soil stays relatively moist beneath mulch, roots do not have to grow deep and work hard. They can stay near the surface. This means that once you start mulching, you are committed to maintaining it. If you change your mind and remove the mulch in midsummer, your plants may quickly turn crispy and die from lack of water.

Fluff mulch once in a while so it doesn’t get too packed down. Break up the dry crust so water can filter through. If your mulch starts sprouting — perhaps because you have used oat straw or hay with lots of seeds — flip the mulch upside down on top of the unwanted seedlings to choke them off.

Refresh or renew mulches in ornamental beds and around shrubs and trees. Using the same type of mulch in these plantings every season is fine, especially because you’ll probably just need to refresh what’s already there. To perk up tired-looking decorative mulch, sometimes just raking will bring larger, more colorful material to the surface. If that isn’t enough, you can add new mulch. Remember to remove as much as you replace. For most mulches keep the mulch layer 2 to 4 inches deep, and no thicker. Heaping new mulch on old isn’t a problem in itself. Rather, the danger is in overmulching — increasing 3 inches of wood chips to a 6-inch layer, for example. More is not better. Overmulching is likely to kill your plants, maybe not overnight but after a season or two.

Don’t use the same mulch year after year in your vegetable garden. This advice is based on the same principle that it is not a good idea to plant the same crop in the same place year in and year out. A good mulching may last for several seasons. When finally it does decompose, it should be replaced by a different material.

Apply thicker mulches to sandy, gravelly soils and thinner mulches to heavy clay soil. Avoid mulching at all in low-lying spots — places that are sometimes likely to be “drowned” with water. Although it isn’t always necessary, you can remove mulch during a particularly rainy period to prevent the soil from becoming waterlogged.

Choose the right mulch color for where you live and the plants you’re mulching. Darker mulches like buckwheat hulls and walnut shells absorb heat and warm the soil beneath them. Lighter mulches, such as ground corncobs, reflect light and heat the soil less.

Cultivate around your plants before applying mulch. This is important if your plants have been in the ground awhile without mulch. Loosening the surrounding soil and removing any weeds at this stage will pay off later. Be sure to water the plants generously. Spray with kelp solution or spread fertilizer on the soil, too. After you have prepared the ground, top it with the mulch layer.

After-the-fact mulching cannot do much good if the ground is dried and baked hard. This little bit of advance mulching preparation shouldn’t be too much of a chore. Keep in mind that once the mulch is in place you won’t have to do any more of this type of work for the rest of the season.

Wait to apply your first mulch until after plants started from seed are established. Mulch between the rows first, not right on top of where the seeds were planted. You can begin to mulch the seedlings just as soon as they are an inch or two higher than the thickness of the mulch. Leave an unmulched area about 6 inches in diameter around each plant for about two weeks. Later, when the mulch is good and dry, bring it within 2 or 3 inches of the stems.

Heavy mulch is most effective if applied when the ground is moist. If the ground is too dry to start with, it will tend to stay dry for the rest of the summer unless there is a real cloudburst.

Do not apply wet mulches, like new grass clippings, on very hot days. When the temperature is above 90°F, such mulches, when wet, tend to generate so much heat that they actually can kill the plants they touch.

Peel off “books” or “flakes” of straw and place them between rows of vegetable plants. This will make a clean path for you to walk on during rainy days and will keep the weeds down. If any weeds come through in force, add more layers.

Mulching with straw. Place thick layers from straw bales between rows in the vegetable garden to keep weeds under control and to keep plants clean.

Bacteria and earthworms are strong allies for any gardener. Without help from lots of microbes in the ground, mulch would never decompose, and the vital elements that are tied up in organic matter would never be released. Worms predigest matter in the soil and liberate chemicals in their castings that plants can use for nourishment. Worms are also excellent indicators of how useful a material will be as mulch, since their presence and activity depend on moderate soil moisture and temperature conditions.

Earthworms are affected by changes in season and temperature. Earthworms are least active during the hottest months and the coldest months. In the summer they can be coaxed into working harder if you keep enough mulch on the garden to keep the soil moist and cool. In the late fall earthworms need to be protected from sudden freezing. Mulching will help protect against rapid temperature changes in the soil.

Be alert for signs of nitrogen deficiency when you use some organic mulches, such as fresh sawdust or wood chips. Bacteria that break down the mulch and turn it into humus require a large amount of nitrogen themselves, so they take nitrogen from the source most available to them: the soil. This may make plants look yellow and stunted because they are not getting enough nitrogen. Apply your regular fertilizer as directed. Water well.

Mold can develop in too moist or shaded organic mulch material. To get rid of mold, turn the mulch regularly. Mold does little harm. It seems to offend the human eye more than it bothers soil or plants.

Mulches are excellent places for disease spores to over-winter and multiply. Remove and dispose of mulching material that you know has become disease infested. Don’t till it into the soil.

Frustrating fungus. Most mulch fungi are harmless, but spore masses from the cuplike artillery fungus can create a mess that is difficult to stamp out.

Disguise plastic mulch by covering it. If you recognize the advantages of plastic mulch but are offended by the sight of it in your garden, cover the plastic under a thin layer of something else, like pine needles, crushed stone, wood chips, or hulls of some kind.

Apply water-soluble fertilizer through slits in the plastic. If plants under a plastic mulch show signs of needing fertilizer, simply dissolve fertilizer in irrigation water and run it through slits cut into the plastic.

Wood and bark landscape mulches can be hosts to several fungi that may look strange but are harmless. Many fungi break down wood and bark into material that plants thrive on.

On the other hand, the artillery fungus is a real nuisance along the East Coast. It is so small that it’s easy to miss at first. Look closely and you’ll see what resemble tiny cream or orange-brown cups holding wee black eggs.

Trouble comes when the fungi reproduce. When light, heat, and moisture conditions are just right, they actually shoot these black eggs (sticky spore masses) at light-colored surfaces, such as a white house or bright car. The “egg” is like a speck of tar. The sticky spore masses are very difficult to remove without damaging the surface of the house or car. One or two spots aren’t so noticeable, but en masse they are an unsightly mess. Even if you get them off, the remaining stain requires repainting.

To reduce the likelihood of artillery fungus problems, rake mulch to disturb the fungus and dry out the mulch. Periodically top off decaying mulch with fresh mulch composed of at least 85 percent bark; or replace wood-based mulch with other types, such as black plastic or stone, in areas adjacent to buildings and parking areas.

Ornamental plants give beauty to our landscapes. They are the trees, shrubs, perennials, annuals, and bulbs placed and cultivated for their visual appeal around our homes and businesses. Every year homeowners spend millions of dollars to add height, variety, texture, and color to their front and backyards. Mulching is a simple way to help protect and enhance that investment.

Mulching is an integral part of landscaping for several reasons. A richly textured, attractive mulch adds a professional touch to any ornamental bed. Mulching an ornamental bed conserves water, controls weeds, mediates soil temperature, and stops erosion. Healthy ornamentals improve a property’s value, and they give you more enjoyment of your time at home.

Because most landscape plantings are perennial in nature, you can use more permanent mulching techniques and materials. It’s worth the time and effort to lay down a landscape fabric and cover it with stones if you don’t plan to remove it in the fall.

Mulch for landscaping, be it for a single tree or a handsome mixed bed of perennials, shrubs, and annuals, should appeal to the eye. Decorative mulches include shredded barks, stones, wood chips, and cocoa hulls. Ground covers such as thyme and pachysandra can act as excellent living mulch, keeping weeds at bay and soil in place in difficult or large areas.

Geotextile fabric topped with shredded bark, natural or colored wood chips, or stone is a popular landscape mulch. Redwood chips placed over landscape fabric is a good way to add color.

The basics of mulching apply to ornamental use, just as they do for vegetable gardens. Choose your mulch thoughtfully. Before applying any mulch, water the ground well and remove all weeds. Fertilize your plants according to package directions. Apply mulch evenly as if it were a blanket, 2 to 4 inches deep, depending on your mulch and the soil conditions. Don’t place mulch against any living stems, trunks, or branches.

To refresh old mulch, give it a light raking to fluff it up, renew the color, and break through any crust. If that doesn’t do the trick, remove an inch or two of the organic mulch (wood chips, bark). Then top with new mulch, adding about as much as you removed. Keep the depth of the mulch in the 2 to 4 inch range. With mulch, more is not always better. Overmulching can be fatal to the plants you are trying to help.

Probably the number one cause of death for newly planted trees and shrubs is the lack of adequate water. We already know that mulch can help solve that problem. Mulching around the tree base also reduces the incidence of lawn mower damage, another cause of tree death. A good covering of mulch, 3 to 4 inches deep, right after planting will go a long way toward protecting the base of your trees. Before mulching a new transplant, clear away weeds and grasses from the soil surrounding the trunk. A circle 3 to 5 feet wide is a good start. Water generously. Then mulch that cleared area to suppress weeds and grass. This boundary will also help you resist the urge to mow right up to the trunk of the tree.

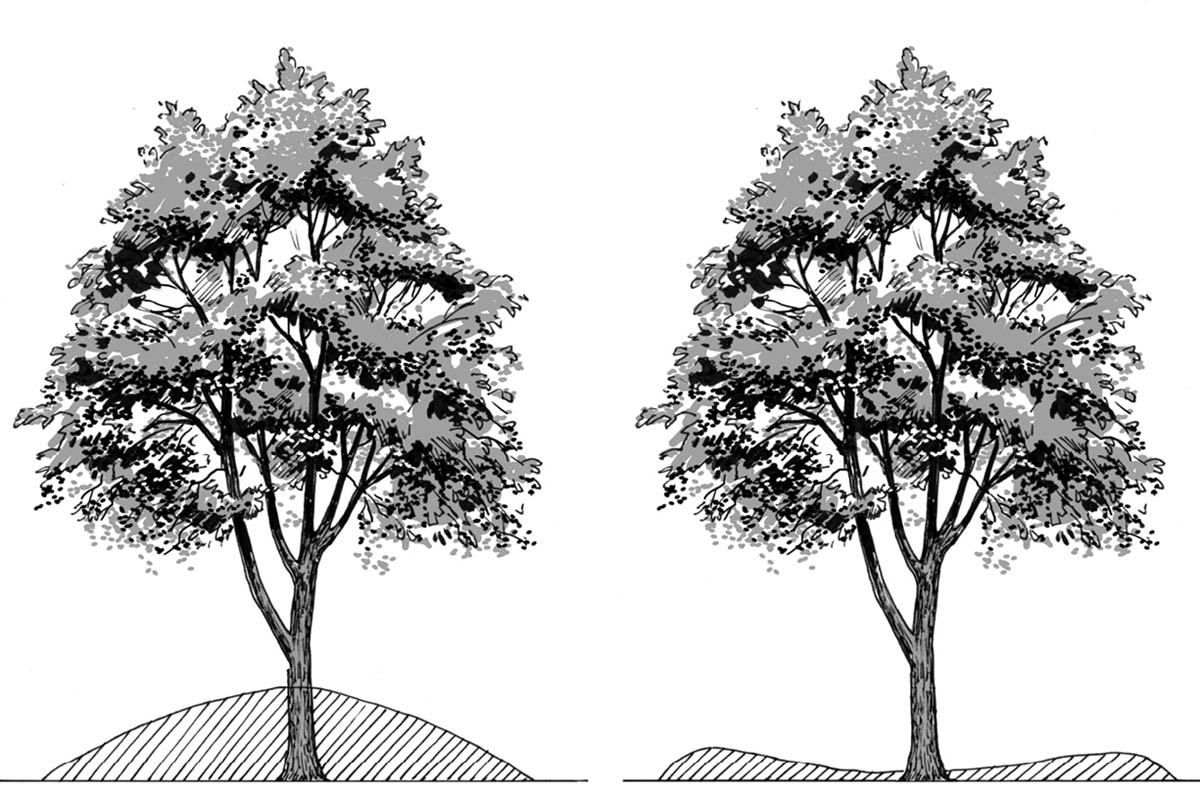

Established tree mulching. Mulch an area at least as large as a tree’s dripline to reduce weed competition for water and nutrients needed by the tree.

For mulching under established trees, clear weeds and grasses to the tree’s dripline, which is the shady area beneath the tree’s canopy. If that’s too overwhelming an area, clear as large an area as you can. Something is better than nothing.

Next, apply organic fertilizer as directed, then water the area well. Top with 3 to 4 inches of organic mulch.

A work-saving alternative when temperatures drop in the fall is to spread fresh wood chips out to the dripline. They’ll do double duty. The heat from their decay will kill grass under the tree canopy and the chips will act as mulch, too.

Organic mulches like wood chips, shredded bark or nuggets, cocoa hulls, pine needles, leaf mold, and shredded leaves are all smart choices for mulching trees. These mulches decompose, adding to the soil nutrients that are easily depleted by all the tree’s shallow feeder roots. Crushed stone and gravel are fine, but they won’t enrich the soil. Be careful when applying any rock-type mulches around woody plants. Rock mulches can do serious damage to woody plants if they jab into the base of the tree. Remember to keep all types of mulch at least 6 inches from the tree trunk.

To mulch shrubs, follow the basic mulching guidelines (see Mulching Basics). Remove as many weeds and grass clumps as possible, especially in the shady area under the shrub’s branches. Apply fertilizer if needed, according to package directions. Water well. Then apply your mulch of choice in an even 2- to 4-inch blanket over the root area. Remember, an organic mulch such as leaf mold or shredded bark will feed your plants for many months to come. Avoid placing mulch in direct contact with the shrub’s base and branches.

Don’t succumb to the common practice of building a volcano of mulch up around a tree or shrub. If you do, you might as well say last rites for your plant. Dark, moist mulch right against bark is the perfect place for insects, diseases, rot, and gnawing critters to feast.

Think “blanket of mulch” instead. Start mulch at least 6 inches from the tree trunk or shrub base. Apply an even layer, 2 to 4 inches deep, over the entire area beneath a tree or shrub. Doing this will smother weeds and allow water to seep evenly into the soil.

No volcano mulching. A mulch volcano (left) can lead to problems. Proper mulching (right) leaves space around the base of a tree.

New beds. Mulching a new mixed bed of perennials and annuals is easy. Put in the plants. Water generously, and fertilize as needed. Carefully shovel mulch around the new transplants, making sure not to allow mulch to rest against the stems or on the crowns. Mulch on crowns and against stems invites rot, disease, and insect damage. Spread the mulch until you get an even blanket of material that is 3 to 4 inches deep.

If your plants are small, such as young annuals, 2 inches of mulch is fine. If you’ve grouped annuals close together, don’t sprinkle mulch between the flowers. Just start mulching an inch or two outside the group. Remember that one of your major interests for mulching is weed control, meaning that a deeper mulch layer is best where weeds might be tempted to take root.

Keep a close eye on your mixed bed for a week or two. If your plants start to turn brown or look wilted, check to make sure mulch isn’t in direct contact with them. If it is, pull away the mulch. As a reminder, mulch is harmful when placed too close to stem and leaves. It can stifle airflow, trap moisture, and become home to insects and diseases.

Established beds. Mulching an established mixed perennial bed is best done in spring after the soil has warmed. At this time the plants will be filling out and you should be able to move easily through the garden. Some perennials are slow to emerge, so walk (and mulch) carefully. Also watch for sprouting seeds; they may be developing into more perennials you’ll want to move or cultivate in place.

If you’ve planted in clusters or groups, mulch outside the clusters and cultivate inside. You want your perennials to have as much room to fill in as possible. The ultimate goal is to have a perennial bed full of, well, blooming perennials! Every year your perennials should spread farther and wider so you’ll need less and less mulch.

Weed, water well, and fertilize as needed before mulching. If mulch from the last season remains, hoe to loosen it before topping off with a new batch.

If you just don’t get to mulching early on in the spring season, don’t worry. Anytime is better than no time. Just remember to weed and water well in preparation for mulching. Then allow the foliage to dry before shoveling on the mulch. Be sure to keep the mulch an inch or two away from the base of each perennial to avoid causing rot to their crowns and stems. Otherwise, mulch in their crowns and against stems is likely to cause rot.

For an attractive landscape that saves money and gives your plants the most nutrition, try a two-layer approach to mulching ornamentals. It’ll look great immediately, and even better next season after the leaf mold has fed your plants.

Generally, if you mulched in the spring, then you do not necessarily need to mulch in the winter. For fall transplants (shrubs and perennials) and late-season divisions, though, a loose winter mulch of evergreen boughs, pine needles, or pine bark chips provide excellent extra protection. The same is true for marginally hardy plants and temperamental shrubs. Use a light mulch that won’t mat down, resist water, or make too comfortable a home for rodents. Whole leaves, although handy, aren’t a good idea because they will clump, mat, keep water out, and suffocate anything below. Shredded leaves work well, though. Remember to remove the light mulch in spring when you see new sprouts. Keep some boughs on hand in case you need to cover plants quickly as protection from a late frost.

Both rhododendrons and azaleas prefer acidic soils, and your mulch selection can play a part in helping them get the soil type they want. Choose an organic mulch, such as shredded leaves or pine needles. A dry mulch of shredded leaves, spread 10 to 12 inches deep, can be laid down at planting (these will decompose quickly to give you a 3- or 4-inch layer). A 2- or 3-inch layer of pine needles will also do the trick, as will wood chips, if sufficiently weathered. Mulching helps cool the plants’ shallow roots during the summer and will retain soil moisture year-round for these mostly evergreen plants.

Rose mulching offers a shining example of the differences between summer and winter mulches. Summer mulching is done in the spring to control weeds and maintain soil moisture. Winter mulches, put down after the ground has started to cool in the fall, serve to protect the plant from temperature extremes and soil heaving.

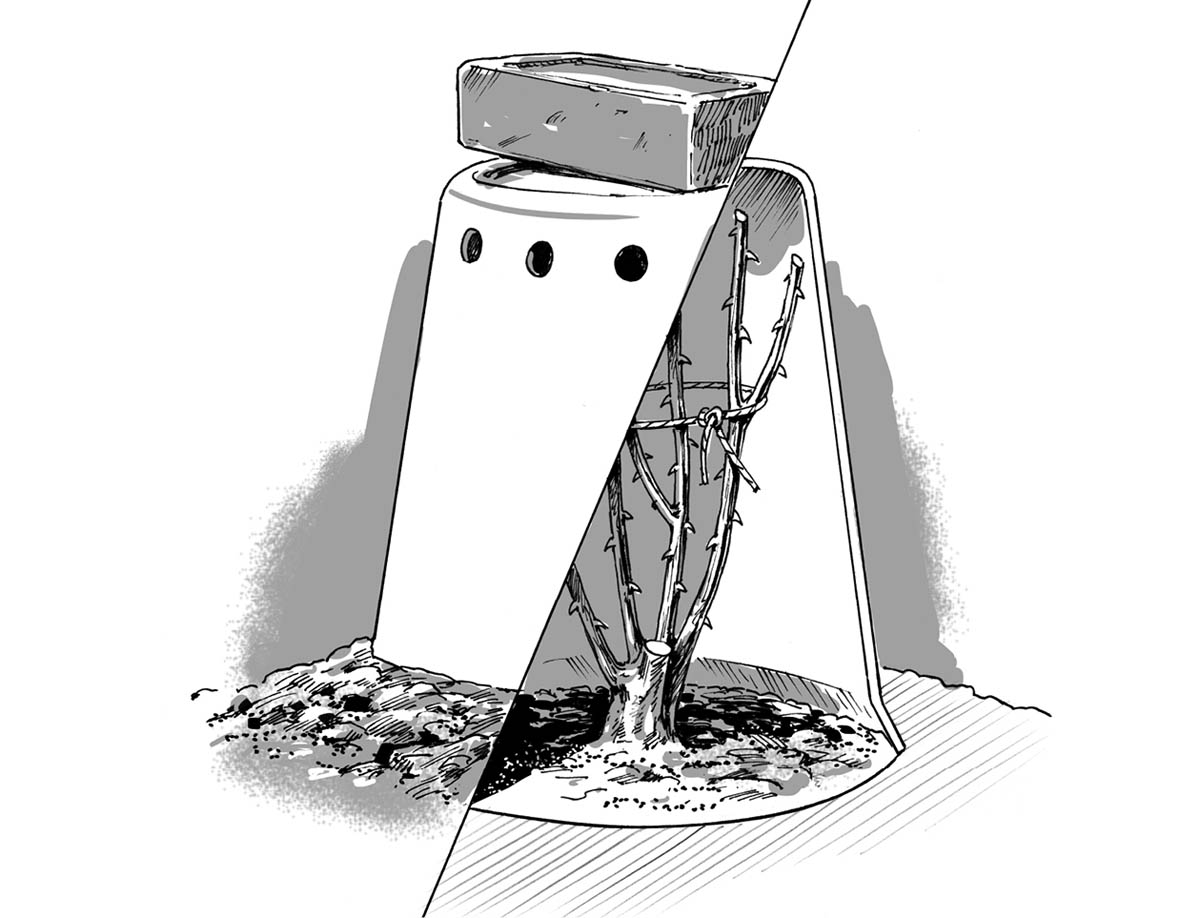

Winter mulching for roses. Here are three methods for mulching roses in winter. Whichever system you select, water the soil well before covering your roses and remove the mulch in the spring before new growth begins. If the winter mulch is left on until the buds start swelling, the new growth may be put into shock when you uncover it.

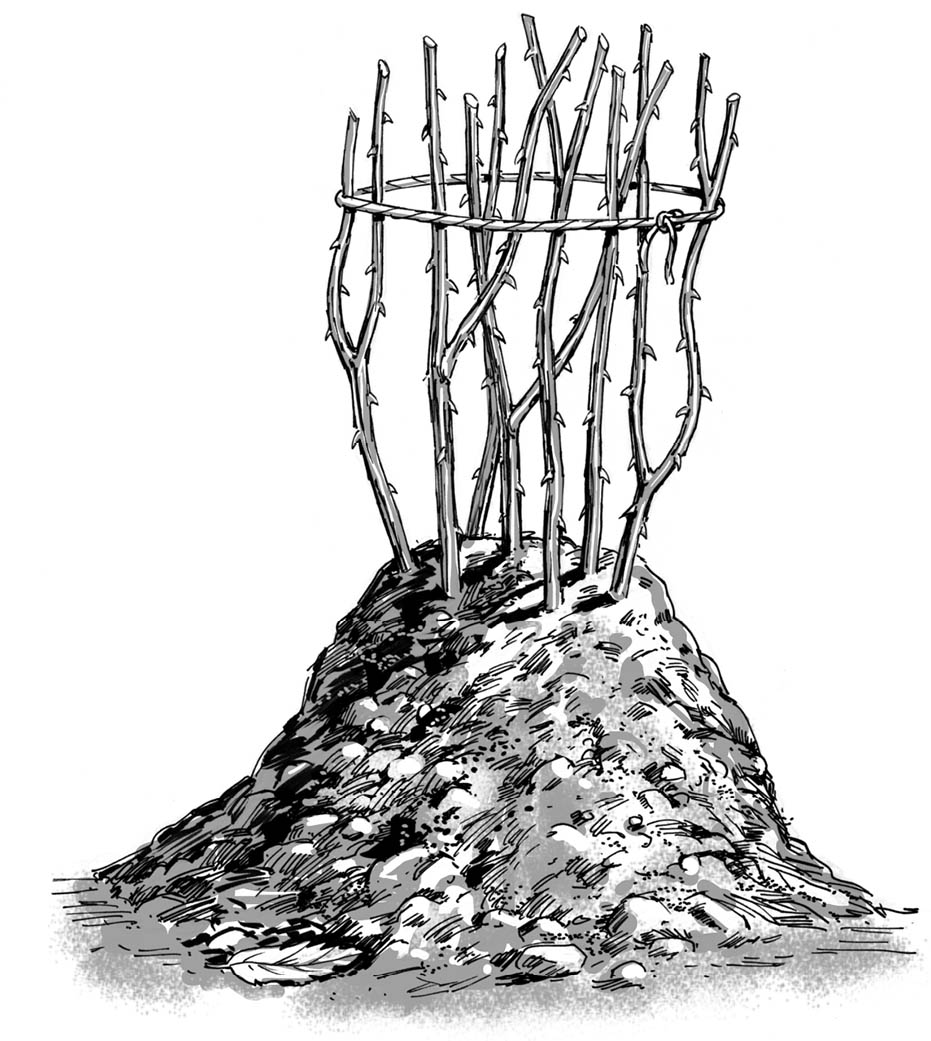

Take soil or organic mulch from elsewhere in the garden and make a mound of 10 to 12 inches around the base of the rose bush. Do this after the first hard frost. If you do this too early, the roses may be fooled into a late growth spurt, which will delay dormancy and lead to more, not less, winter injury.

Mounded soil. For mulching roses in winter, mound soil/mulch at least 10 inches around each bush.

In areas where the temperature stays well below freezing for most of the season, you will need to provide some additional protection. Some growers lean toward the Styrofoam rose cones that fit around the mounds; others prefer ground corncobs, sawdust, or chopped leaves. Synthetic fiber blankets are an attractive winter protection. However, rose cones can cause overheating during those warm, sunny January thaws. To help keep your roses from “frying,” poke a ventilation hole in the top.

Rose cone. To keep a lightweight rose cone in place, weigh down the cone with a brick.

Wire cages filled with leaves or compost are often used instead of the Styrofoam cones. These cages needn’t be stuffed to the gills with leaves. An overstuffed cage makes for poor air circulation that may lead to disease.

Wired cage. A cylinder of wire mesh holds mounded soil in place around rose canes.

Summer mulching roses. Mulching roses during the growing season prevents damage to shallow roots during cultivation. Be careful not to mulch right up to the base of rose bushes, and do not overwater the beds. Moist, damp conditions can foster many rose diseases.

Mulching hardy bulbs is not essential. But in a cold-winter area the insulating value of a thick organic mulch can’t be overlooked. Two to 4 inches of shredded leaves, bark nuggets, wood chips, corncobs — just about any mulch that doesn’t pack down — is fine for bulbs. Apply mulch after the ground is frozen. Remove the mulch in the early spring at the first sign of green sprouts.

Shredded bark, fine bark nuggets, cocoa hulls, or buckwheat hulls are perfect summer mulches for showcasing expensive specimen roses. This is one instance where the added cost of these mulches might be justified. The dark, rich colors associated with these types of mulch can really accent an already impressive rose display.

Decorative, organic mulches are also excellent for the easy-care rose varieties. If you fertilize and water well before applying mulch to ever-blooming Carefree Wonder roses, for example, there’s little else to do for the season but water occasionally, relax, and admire the blossoms.

Many annual and perennial vegetables benefit from mulching during the year. Following is a list of commonly grown vegetables accompanied by recommendations of how and when they might need mulch. While considering the suggestions made here, keep several things in mind: (1) the general mulching guidelines offered earlier in this book (see Mulching Basics), (2) your own experience with a particular vegetable, (3) the climate in your area, and (4) the idiosyncrasies of your garden, such as the soil condition, drainage, the amount of sunlight, and the types of pests.

When seeds are first planted, mulch between rows.

When plants are established, move mulch closer to plants.

If you are just starting a new asparagus bed, mulching probably is not necessary until the second spring. However, if you live in a cold place, you will want to mulch for winter protection even in the first year. Hay, leaves, and straw are just a few mulches that are excellent for winter protection of asparagus.

In the spring there is no need to remove winter mulch. The tips will come right up through the mulch whenever they are ready. Eight inches of hay mulch is not too much for asparagus. The primary function of this mulch is weed control, but it may have other fringe benefits.

To extend your asparagus season, divide your bed into two parts in the spring. Mulch half of the bed heavily with a fine material such as chopped leaves or leaf mold. Leave the other half unmulched until the shoots begin to break through the mulched half. Then mulch where you did not mulch before. This technique should extend the asparagus season, because the part of the bed that got its start without mulch will begin to bear one or two weeks earlier than the part that started out with mulch. Don’t worry about weed control with the temporarily unmulched bed — those first asparagus shoots will poke through early in the season, long before any weeds take hold. If you are prompt with your second application of mulch, you’ll still have excellent weed control.

Mulching asparagus. Use mulch not only to control weeds but to extend the harvest of asparagus.

You can mulch beans two or three weeks after planting. Mulching is especially beneficial to beans because it inhibits weed growth. The finer the mulch the better, particularly if you like to plant beans in wide rows. Bean roots grow close to the surface, meaning that any deep or extensive cultivation to halt weeds will also result in undesirable root pruning of the beans themselves.

Beets prefer a nonacidic soil, so it is probably better not to mulch them with pine needles exclusively. You can use just about anything else for mulch. In fact, adding ground limestone or lime to the soil, or mixing it with the mulch, may be a good idea. Ideally, leaves or leaf compost should be spread on beet plots at least once a year, then worked into the soil as fertilizer.

A light mulch of grass clippings can be put down right after planting beet seeds. Doing so will conserve moisture and prevent the sun from baking the soil hard. As soon as the sprouts appear, pull this mulch back a bit for a while because beets are highly susceptible to damping off, which is a fungal disease promoted by damp, stagnant air around seedlings. As the growing season progresses, increase the thickness of the mulch by adding more layers of straw or hay. And after the rows have been thinned, tuck the mulch in close to the maturing plants. This procedure seems to work well for turnips and rutabagas, too.

Broccoli and cauliflower can be mulched shortly after the plants have been moved outdoors and set in the garden. Any nonacidic organic mulch is fine — it will preserve moisture and discourage some insects. Late in the season the mulch can extend a plant’s productive time. Broccoli and cauliflower can stand a maximum of 4 to 6 inches of organic mulch.

Polyethylene plastic works well with broccoli. If you use it, lay the plastic, cut holes, and transplant through the openings. A little fertilizer and lime ahead of time is probably in order.

After your transplants are well established, partially decomposed mulch can be tucked right up under the leaves around your cabbage plants. This may slow their growth somewhat, but they will grow tender, green, and succulent.

Light-reflecting mulch is especially suitable for cabbage. It discourages some disease-carrying aphids.

If you live in a climate that normally experiences mild winters, you might like to plant cabbage seed and cover the beds with a mulch in the late fall — in November or early December. Re-cover the bed with coarser mulch, such as twigs or evergreen boughs, as soon as the seedlings appear. In spring, when you uncover them, you will have some hardy babies for early transplanting.

Cantaloupes and other melons need lots of moisture as well as heat, from the time they come up until they are fully grown. Research has shown that larger yields result when green IRT plastic mulch is used where the melons are planted. This type of mulch helps to warm the soil, eliminates weeds, and maintains a more constant supply of water to the roots.

A thick organic mulch is designed to do pretty much the same thing as plastic mulch. Hay, grass clippings, buckwheat hulls, cocoa shells, and newspapers work fine. It probably is better to stay away from sawdust and leaves. The mulch should be in place before the fruit develops, because handling may damage the tender melons. Once the fruit is formed, it will be resting on a clean carpet of mulch and won’t be as prone to rot.

Mulch should be used sparingly on carrots. When you sow carrots, you might want to spread a very thin mulch, say of grass clippings, over the beds to prevent the soil surface from forming a crust that the sprouting seeds can’t break through. Water this mulch if you like, but be careful that the tiny seeds don’t wash away. When the slender seedlings come up, be sure that the mulch does not interfere with them.

Have you tried leaving your carrots in the ground during the early winter months to save on storage space in the house? They can be kept in the ground, covered with a heavy mulch to prevent freezing and thawing damage. Once dug up they won’t keep long, but you may prefer them to frozen or canned carrots from the supermarket.

The traditional way to “blanch” celery is with a soil mulch. To do this, pull earth around the plants as they grow higher, until finally, when the celery is fully grown, the celery rows are about 18 inches high and only the green tops are showing. As a cleaner alternative, try an organic mulch rather than soil to blanch your celery. Chopped leaves are best; whole leaves may dry out and blow away.

Celery that is protected with a deep mulch will produce crisp, tender hearts until Thanksgiving or later. Ideally the heavily mulched rows should be covered with plastic, or some other waterproof material to form a tent. With this type of protection, the ground stays dry and will not freeze too hard. You will be able to dig out celery any time you want it, even in midwinter. Just shovel away some snow, remove the tent, and uncover your desired amount of celery. Celery that is protected this way keeps better than if stored in a root cellar.

Mulching celery. For cleaner plants, blanch celery with mulch, such as chopped leaves or newspaper, instead of soil.

Some gardeners keep a permanent organic mulch on their corn patches. At planting time they just run a straight line with a string and push their corn seeds down through the mulch with their fingers.

Permanent mulchers argue that crows seem to be nonplussed by the heavy layer of mulch over corn. Without this mulch crows often will pull out small corn plants nearly as fast as they show aboveground. They are after the tender, just-sprouted kernels. If the corn has had a chance to get a good head start under mulch, the plants will yield disappointing results to the average crow.

Where soil warmth is a concern in late spring/early summer, hold off on mulching corn seedlings until the plants are about a foot tall. Use any mulch that preserves soil moisture and adds nutrients to give the corn an extra boost.

Chopped leaves, leaf mold, straw, and old hay are good for mulching cucumbers. These types of mulch can be put around the plants when they are about 3 inches high and before the vines really start to extend. Cucumbers require a lot of moisture, which the mulch will help to retain. Some organic mulches will invite slugs, snails, insects, and diseases to your cukes. To be on the safe side, keep the mulch 3 or 4 inches away from the main plant.

Eggplant needs all the warmth it can get. Red and black plastic mulches have been used successfully to warm soil and increase fruit yield. However, if you are planning to use organic mulch, don’t apply it until after the ground has really had a chance to warm up. Also, avoid disturbing the earth immediately around eggplant. Once the soil is warm enough, mulch will smother most weeds before they grow big enough to be pulled.

The roots of these finicky plants prefer to grow and feed in the top 2 inches of soil. If there is too little moisture there, the leaves of eggplant turn yellow, become spotted, and drop off. If there is too much moisture, the plant will not bear fruit. Mulch can help to keep a uniform supply of moisture in the soil.

Garlic can be mulched when the plants are 6 to 8 inches high. Use a fine mulch like hulls, grass clippings, or chopped leaves. For more advice see the entry on Onions.

Kale is an incredibly hardy vegetable. It can be grown nearly any time of year. A fall or winter crop of kale may be left in the field, covered lightly with something like hay or straw. Later in the winter simply remove the snow (one of the mulches kale seems to like best, by the way) and cut the leaves as you want them. Kale will sometimes keep this way all winter, provided that it doesn’t get smothered by ice after a thaw.

Leeks and scallions can be mulched lightly with anything from straw to wood shavings. Just be sure that the mulch does not interfere with the very young seedlings. For more advice see Onions.

Leaf lettuce does well in semishade and in rich soil. A coarse mulch such as twigs, rye straw, or even pine boughs can be used in the seedbed. As the leaves grow, move the mulch right up underneath them. This does four things: It holds the soil moisture, keeps the leaves from being splashed with mud, prevents rot, and maintains the cool root zone that this cold-season vegetable requires for optimum production.

You can apply as much as 3 inches of mulch as soon as head lettuce is 3 or 4 inches high and has started to send out its leaves.

Onions can and should be mulched during long hot spells. Chopped leaves can be sprinkled among the green shoots even if they are 2 or 3 inches high. Mulched onions will grow more slowly and be more succulent than onions grown without mulch. A little more mulch can be added as the tops develop.

In places where winter is not as harsh as northern climates, parsley can be protected by mulch throughout the winter. It can be planted in cold frames in August — or even later — covered with hay, left in the frames all winter, and transplanted to the garden in the early spring. Parsley is susceptible to crown rot, so summer mulches should be kept 5 to 6 inches away from the plant.

Parsnips do not grow well in tight, compacted soil: Instead of growing one straight root, they divide into three or four, which makes the root worthless. Mulching can help here by preventing soil compaction. Note that parsnips prefer a soil with a pH of about 6.5, so don’t use an acidic mulch.

Most gardeners can eat parsnips from their gardens all winter if the plants are heaped high with leaves or some other protective mulch as cold weather moves in. Parsnips store very well. Don’t harvest them until after the first heavy frost; they won’t have reached their peak of quality until then anyway.

In northern regions gardeners don’t have any trouble creating cool and damp conditions for peas without using mulch. It is easy to overdo mulching peas in a cool climate, but the soil around peas does need to be cool and damp for germination and growth.

To grow peas in warmer places, or to grow pea varieties like Wando later in the summer, mulch with a thin layer of grass clippings, straw, or hay when the seeds are sown. As the plants get started, you can increase the mulch to insulate the soil from the atmosphere and the hot sun. Mulching in this way all but ensures a cool, moist root zone.

The last time you pick your peas each season, pull up the whole vine before you remove the pods. This should help save your back. The vines should be stacked and saved, too. Chopped or whole, they are a nitrogen-rich mulch that can be used on the garden, except on other peas (for the same reason you rotate crops — to stave off disease problems).

The growing habits of peppers are very much like those of tomatoes. Set transplants out in red or black plastic mulch, or black paper mulch. This mulch will collect the heat of the day and help maintain a warm soil temperature for a while into the night.

Potatoes, if you use mulch, don’t even need to be planted! You can lay seed potatoes on soil or on top of the previous year’s mulch, then cover them with a 12-inch-thick layer of hay or straw. You can harvest early potatoes from their thick mulch bed, then replace the covering.

Mulching potatoes. Harvest new potatoes from under mulch and re-cover plants to allow additional tubers to develop.

Deep mulch also seems to thwart pesky Colorado potato beetles, because it provides an environment conducive to predators of these beetles.

Pumpkins profit from freshly cut hay, composted leaves, and straw. Mulch around each hill. As the crop starts to mature, use any coarse mulch that keeps the fruit off the ground.

Mulch is not recommended for quick-growing plants like radishes, as there usually is not enough time for the mulch to do them any good. For the most part, plants that prefer cool, moist soil respond better to mulches than those plants that revel in hot sun and dry soil.

Spread a thick mulch of strawy manure over the bed after the ground freezes in the winter. In the spring rake the residue aside to allow the ground to warm and the plants to sprout. Then draw the residue, together with a thick new blanket of straw mulch, up around the plants. Hay, leaves, or sawdust also makes excellent mulch for rhubarb.

Once the seedlings are well established, spinach and chard can be mulched with grass clippings, chopped hay, straw, or ground corncobs and be better for it. Spinach prefers nonacidic soil, so avoid pine needles and sawdust. In any case, don’t put down a summer mulch until the leaves have had a chance to make a good growth.

Squash can use an extra dose of mulch, especially during hot, dry spells. The mulch, whether it be hay or chopped leaves, can be as deep as 4 inches. Leave the center open so that some heat can get to the middle of the plant. The mulch over the rest of the patch will preserve moisture and discourage some bugs.

Sweet potatoes are ravenous feeders and are happiest in plenty of moisture. Old leaves and grass clippings make good mulches, as do the old standbys, hay and straw. Consider black plastic as a soil-warming mulch if growing sweet potatoes in northern climes.

Some vegetables such as tomatoes (as well as peppers and corn) need thoroughly warmed soil to encourage ideal growth. A mulch that is applied too early in the spring, before soil temperatures have had a chance to climb a little in frost-zone areas, will slow such crops.

However, black and red plastic mulches, used in commercial cultivation, are increasingly popular among gardeners who want earlier crops and higher yields. These plastic mulches warm the soil so you can start planting earlier and continue harvesting longer. They also conserve moisture and control weeds. They are best applied either before or soon after plants are in the ground.

If you choose not to use plastic, a good time to mulch with other materials (hay, straw, chopped leaves) is right after the flowers appear. Blossom-end rot can be caused by a variable moisture supply. Mulch keeps a more consistent supply of moisture around the roots of the plants. If you have lots of mulch and few sticks to use as tomato stakes, forget about staking. Let your plants run around freely over the mulch, and let the fruit ripen there.

Here is still another plant that should not be mulched until the soil is really warm — or use black or IRT plastic mulch to warm the soil. Watermelons demand all kinds of soil moisture. The best time to apply organic mulch is when the soil has been dampened thoroughly. Up to 6 inches of mulch can be spread over the entire patch, if you like, to prevent rot and to keep the fruit soil free.

Like any other cultivated plant, fruit trees and berry bushes benefit from mulching. In addition, mulching helps to keep fruit clean and palatable for harvest. Following are recommendations for mulching these fruits in spring, summer, autumn, and winter.

As the snow starts to melt during those first warm, sunny days of spring, loosen mulch where it has been crushed by snow, if you like, but don’t remove it too early. The plants may be frost-heaved out of the ground or begin to grow too soon and get nipped by frost. Spring is a good time to scout around and see what you can scavenge in the way of mulching materials. It also is the time to plow, spade, or rototill winter mulch into seedbeds where you will be planting your annual plants.

Move protective mulch away from plants gradually, and let it lie off to the side, but within easy reach. If possible, remove the final layers of mulch on a cloudy day so that any young shoots that have started are not blasted suddenly by brilliant sunshine. Once the winter mulch is off completely, leave it off for several days, or even a couple of weeks, before you start to mulch again. Give the earth plenty of time to warm up.

In the late spring start mulching again. Your aim is to conserve soil moisture and control weeds before they get a head start. Mulch far enough away from your fruit trees — out at least to the dripline (that’s the outer perimeter of the tree if you are looking straight down on it) — to be sure your mulch is directly over the tiny feeder roots.

Summer is the time when mulching should start to pay dividends. During hot spells, roots should thrive in the weedless, cool, moist ground under the mulch. You need to do nothing except have a look every now and again, and renew the mulch wherever weeds show signs of getting the upper hand. Pull any weeds that show up.

Be crafty about choosing materials for summer mulching. Because your fruits will not be tilled, use organic mulches to encourage earthworms into your perennial beds. Worms will help aerate the soil. A continuous mulch around thick-stemmed shrubs and trees should be a coarse, heavy material that allows plenty of water through but that is not going to decay too rapidly (this mulch should last for several years).

One thing to look out for is crown rot in small fruits — strawberries, for example — during the early summer months. If there have been especially heavy rains, postpone your mulching until the soil is no longer waterlogged. Do not allow mulches to touch the bases of your plants. The idea here is to permit the soil to stay dry and open to the air around the immediate area of the plant.

The longer the perennial’s roots can stay at work in the fall, the better — up to a point. Late mulching can prolong a plant’s growing season because it provides a buffer zone against frost. Roots will continue to grow in soil as long as moisture is still available there. When the soil water freezes and is unavailable to roots, they stop growing. Increase your mulch volume gradually for a while to insulate the soil and to prevent early freezing of soil moisture.

Once the frost has been on the pumpkin more than a couple of times, your plants probably should be given a hardening-off period that is similar to the one you gave them in the spring. Remove the mulch gradually until the plants are obviously dormant and the ground is frozen.

By now you should be collecting materials for winter mulching. Maybe you will want to cut evergreen boughs. They do a great job of holding snow (which is a superb mulch) in places where it might otherwise be blown away. After harvest time, push mulch back away from fruit trees, leaving an open space around the trunks. If you anticipate that a winter rodent problem will develop, remember that you can wrap wire mesh, hardware cloth, or plastic protectors around tree trunks and berry canes.

Fall is the best time to make use of your chopper to grind up plant residues for future use as mulch. Use your rototiller, if you have one, for tilling in leaves between rows. Till in the summer mulch, too.

Mulch your annual beds early — before frost really has settled into the soil — so that earthworms and beneficial micro-organisms can stay at work longer during the cold months.

Mulch perennial fruits after the ground is frozen, so that plants cannot be “heaved” out of the ground when the soil expands and contracts on alternately freezing and thawing days. Note that because winter mulch prevents the absorption of heat in the spring, it doesn’t allow anything to grow until after the last killing frost has passed. Once the killing frosts have abated for the season, you can finally remove the winter mulch.

Apply organic mulches, such as straw, hay, shredded leaves, grass clippings, or bark, to a depth of 6 inches.

Leave a space of several inches between the mulch and the base of trees to deter rodents; use tree guards if necessary.

Apply 3 inches of straw or chopped hay after planting, being careful not to cover plant leaves with mulch.

Add another 3 to 5 inches of straw for winter mulching whenever temperatures stay below 20°F for any extended period of time.

When removing mulch in spring, put half of it in the pathways between rows and leave the other half for plants to grow through.

Apply 3 or 4 inches of chopped hay, straw, or bark as a permanent mulch to the row, or over the entire soil surface after planting.

Maintain permanent mulch by replenishing annually.

Spread weathered sawdust, pine needles, or pine bark mulch 3 to 4 inches deep, keeping it away from plant stems.

Maintain permanent mulch by replenishing annually.

Lay down 2 or 3 inches of an organic mulch, such as straw, leaves, or grass clippings, while planting your bushes. Replenish annually.