CHAPTER 4

THE TASTE OF

RUM

Sugarcane yields sugar when the stalk is crushed and its juice extracted. The juice is reduced by boiling and the sugar is crystallized. The liquid left behind is the molasses. It contains about 5 percent sugar. Along with fermentable sugar, this molasses contains the concentrated flavor of the cane itself and the flavor of sugar caramelized during the reduction of the original juice.

Harvesting sugar cane, the source of rum’s flavor.

Fermented molasses is, with a few exceptions, the raw material of rum. Traditionally, the molasses was fermented by wild yeasts in a slow fermentation that introduced its own complex flavors. This is still the practice for most premium rums today. The notable exceptions are the agricultural rums of the French West Indies that are made from the cane juice itself.

Most modern day rum is produced by distilling molasses in large column stills that operate continuously. These stills turn out a high proof, highly refined, and neutral tasting product. It may be as much as 190 proof (95 percent alcohol). This is the rum that gets mixed with three different kinds of fruit juices and served with a little paper umbrella on the edge of the glass. It is sometimes wood-aged, and sometimes very good. It is certainly an excellent foil for juices and sodas.

Ruins of a sugar factory, Christiansted, St. Croix, US Virgin Islands. Photo by Jet Lowe.

A small amount of the world’s total rum production is made in small inefficient pot stills like the one at Dogfish Head. These stills are loaded with a batch of fermented molasses or fermented cane juice which is then distilled at a fairly low 140- 160 proof (70 to 80 percent alcohol). Pot stills are also used in the production of bourbon, single malt whiskies, and cognac. These inefficient stills leave a lot more of the original cane flavor behind. The rum from pot still production is more likely to be aged in wood (see also Working in the Rum Factory).

It is also more likely to be consumed in a snifter with only a splash of water or a few shavings of ice. It is this premium rum that is the subject of so much enthusiasm and is the ultimate subject of this book.

Questions of Value

Great Rum is relatively cheap when you compare it to spirits of similar quality. Several things conspire to make it so.

First of all, the raw material is cheaper. Molasses is a byproduct of sugar making; Serendipitous Waste you might say. By the time molasses is available for fermenting, the cane has already paid for itself in the form of sugar. It would be wrong to say that molasses is free, but compared to the grapes that make cognac or even the barley that makes scotch, it’s very cheap indeed.

Some rum is made by fermenting the cane juice itself and that’s even cheaper.

Rum, like other fine liquors, is aged in wood to develop complexity and smoothness. The lower cost of raw material means that less money is tied up when the product is stored for long periods of time. Fifteen years of age on a bottle of rum costs a lot less than the same age on a bottle of scotch. The longer the storage period, the greater the price advantage for the rum.

Making molasses is hot work. Photos by Marion Post Wolcott.

Furthermore, rum tends to be aged in warmer places than other liquors. Heat accelerates the transfer and maturation of flavors in a wooden barrel, so a ten-year-old rum is more mature than a more northern spirit.

The labor is cheaper too. Most of the world’s rum comes from countries that are just beginning to industrialize. Single malts and brandies come from mature European economies where workers’ time is very expensive.

The price of fine aged rums also is cushioned by the availability of tremendous quantities of un-aged, almost neutral rum that’s sold as a mixer. This rum is very popular. It has more flavor than vodka and consumers seem to be choosing it more every year. Most producers of fine rum do not derive their income solely from the sale of their best products to a few snifter sniffers. Instead, they are supported by a legion of rum-and-cokers, a battery of blender-wielding bartenders, and a mob of brunchers ordering rum screwdrivers and Bloody Marys.

Finally, rum doesn’t have much snob appeal yet. You aren’t likely to be paying much for decanters, advertising, or two page magazine spreads explaining what rum is and why you should like it.

Storage and Service

Distilled spirits age and improve in wood. Once spirits leave the barrel and enter the bottle, development stops. Those bottles of rum or cognac that you’ve been saving in the cellar aren’t getting better, they’re just getting older. That means that the rum whose label proclaims it to be twelve years old stays twelve years old no matter how long you keep it.

Once a bottle is opened, the flavor begins to deteriorate. The changes are slow, but a bottle of any spirit that’s been opened for a few months will taste different than a freshly opened one. If you have a bottle of premium rum that’s been open for a while, you might want to try an experiment with a new bottle of the same rum to see if the difference is noticeable or noxious.

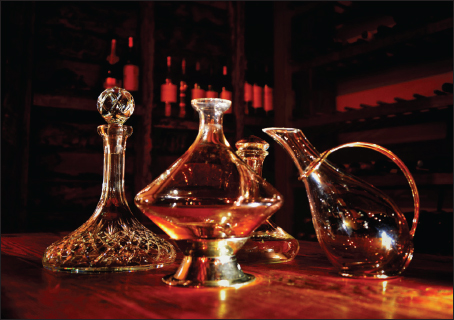

Whatever you do, resist the temptation to pour your rum into a lead crystal decanter and store it there. I know that the decanter is a beautiful light catching sculpture and that there’s something about elegant glassware that makes everything taste better. But it’s also true that the sparkle and the hefty feel of your prized decanter come from the large amount of lead that its glass contains and that this lead will slowly leach out into your rum. Lead, in case you hadn’t heard, is bad for you.

Fine, lead-free crystal shows off the beauty of wood-aged rum. Photo by Rod Waddington.

You don’t have to throw out your heirloom decanter; you can use it safely if you pour your rum into it just before serving and return leftover rum to its low-lead ordinary glass bottle when you’re done. If you’re buying someone a wedding present, it’s nice to know that there are lead-free decanters coming to an expensive store near you.

A fine wood-aged rum invites you to slow down and pay attention to it as you drink. I think that the right response to that invitation is to get the most flavor and enjoyment from the smallest quantity of alcohol. Your choice of a glass can help you do that. The ideal rum glass is shaped like a tulip: a 1.5 ounce (42 ml) portion of rum should just reach the level of its widest part. The walls of the glass should taper inward from there, ending two to three inches (five to seven cm) above the level of the rum. The top of the glass should be no less than two inches (five cm) in diameter. This is shown with greater clarity in the accompanying illustration.

Maybe this glass looks familiar to you.

That’s right, it’s called a snifter, and it’s the traditional glass of choice for cognac for all the same reasons that make it work so well for rum. Larger versions of the same glass enhance the flavor of wine and beer. The stem and base of the glass are common but optional, it could just as easily have a flat bottom* for greater stability.

The reason for this particular architecture is that the aroma of the rum you drink comes from its evaporated vapors. You want the greatest possible surface of your rum exposed to the air to create those vapors, so the widest section of the glass should be right where the level of the rum lies. As the vapors rise, the tapering walls of the glass concentrate them. The two inch opening is large enough to accommodate the upper lip and nose of most adults of our species.

The perfect rum glass.

Glasses should be clean. Check them with your eye and also with your nose. Glasses should also be well rinsed. A soapy film left on a glass is as destructive of flavor as dirt or grease. An alkaline dishwashing detergent, like the kind used in automatic dishwashers, is best. Speaking of grease, don’t make that exquisitely clean and neutral glass greasy with your lips. Fats from foods contaminate glasses and ruin flavors. If you’ve just gorged on potato chips, wipe your lips before you taste. If you’re wearing lipstick, do the same.

Is there a proper serving temperature for rum? You bet there is. The problem is figuring out just what that temperature is. As a liquor gets warmer, it gives off more vapor, and the more vapor, the more flavor. Before you install a snifter warmer in your bar, remember that at very warm temperatures the predominant flavor is going to be that of alcohol. You don’t want to feel the blast of pure alcohol when you drink, you want the subtle flavor that the rum picked up in all those years of aging.

As a liquor gets colder, it becomes thicker. Vodkas and white rums that are served at about 32°F have a sensuous, oily quality. They also seem less alcoholic. This can be a pleasant curiosity of a sensation with a neutral spirit like vodka or a simple one like the caraway-flavored akvavit. Frozen aged rum, however, is a waste. There’s a small echo of the original flavor as the tiny residue in your mouth warms up and a mild burning sensation in your esophagus. It’s not what I paid my money for.

My own tests suggest that the best temperature for serious, barrel-aged rum is just a little below what we like to call “room” temperature. Sixty to sixty-five degrees might be right. This makes for a refreshing cool sensation in your mouth and allows the rum to release its flavor as it warms. If you don’t have a cellar or a cool window sill, chilling your glass will cool the rum slightly. So will a splash of cold water or an ice cube. Again, it’s a question that’s worth an experiment.

Water and Ice

The addition of water to your rum isn’t sacrilegious. When the rum was distilled and aged it was at a much higher proof than you would want to drink (try a drop of 151 proof rum on your tongue for a moment to get the idea). So water is added before the rum goes into the bottle. The makers of the rum have already diluted it for you, so you can feel free to further dilute it to your taste. Typically, fine rums are distilled and aged at about 160 proof or 80 percent alcohol. The rum in the bottle is rarely above 90 proof or 45 percent. On some rum producing islands, the rum is delivered to taverns in casks at very high proof. When you order, you are given a shot of rum in a tall glass and a pitcher of water, so rum and water is very much in the tradition. Even if you are on one of the fortunate islands and the water in question is solid ice, it’s still all right and proper. Of course, you will want the water itself to be pure and refreshing.

Taste

Do you remember being a kid and having to take an unpleasant medicine? You probably had a few techniques to shut out the taste like holding your nose and gulping the stuff down as quickly as you could. Your parents may have chilled the medicine to make its vile aromas less volatile and therefore less likely to fly up to your nose. They may have even followed the dose with a sweet drink or a cookie. Maybe you learned to distract yourself so your attention wouldn’t have to be on the horrible taste and, of course, you sped through the process to get it over with.

The strategy for rum tasting is the precise opposite. You approach the process slowly, focus your attention on the aromas, linger over the flavor. You will look for food that complements the flavor. You will hold the rum in your mouth for a few extra seconds, you linger—even luxuriate.

Your goal is to extract the greatest experience of flavor from the rum, so don’t be in a rush to decide whether you “like” a particular rum or not. Suspend judgment for as long as you can. The minute you decide that you “like” the rum (or not) you stop noticing the rum and start paying attention to your judgment. Your evaluation gets in the way of your perception and tasting is a game of sharpening perception.

Tasting is a lot more fun if you eliminate distractions and concentrate on the rum. You might want to banish competing aromas: no perfumes, colognes, or fruity shampoos in the air. It’s also a good idea to turn the volume down on other stimuli as well. Imagine an afternoon in the shade on a deserted beach. Don’t talk if you don’t have to and keep other sounds down to a minimum.

See

Look at the rum in your glass. Are there sheets of liquid forming a few inches up the side of the glass and falling gently back down to the surface of the rum? Those are called legs or tears. They occur because the alcohol evaporates from the surface of the rum and the remaining water molecules, by virtue of a mutual attraction called surface tension, rise up to escape the alcohol solution below. If the side of the glass is clean, the water molecules—in search of their own company—climb up the side until gravity overtakes them and they cascade back down. It’s a pleasant little sight, but it means nothing about the rum except that it has alcohol and is in a clean glass.

Be sure to notice the color of the rum too. Hold your glass up to the light and inspect the thin line of liquid where the rum meets the side of the glass. Rum fresh from the still is necessarily clear: the vapors that rise from the kettle can carry aroma and flavor but not color. Rum gets its color from being aged in a barrel or from the deliberate addition of caramel. As with beer, color in rum is a liar, but it’s often used suggestively: clear rums evoke the purity of vodka or the raw power of moonshine; dark rums suggest complexity, spiciness, or fruitiness.

With the glass held against a white background, try to probe the deepest color the rum has to offer. This is a moment for poetry. What do you see? Walnut? Mahogany? Cedar? One of the best things about attending to the color is that it slows you down and adds the spice of anticipation to your cup. Some thoughtful rum drinkers have extended this attitude to other areas of their lives and swear they have profited from it.

Swirl and Dilute

Swirl the rum in the glass to increase evaporation and release the bouquet.

Your sense of smell is, after all, excited only by airborne molecules that escape from the rum. It just takes a few escapees to do the job (some aromas can be detected at concentrations of as little as one part per trillion). When you swirl, you coat the inside of the glass with a layer of rum and that layer releases aroma into the air as much as the rum in the bottom of the glass.

If the rum is over-chilled, holding the bowl of the glass in your hand or pouring it carefully into another glass can help make the aroma more available.

This is also the time to add a bit of water. Water dilutes aroma and flavor of course, but it also tames the sensation of raw alcohol and lets other flavors emerge. Alcohol has a taste of its own, a bit sweet with a hint of bitterness, but it can also impart a painful, mouth-burning sensation. You may find that adding water to your glass makes the rum taste harsh for a minute or two.

There’s an odd bit of arithmetic in the chemistry of that splash of water in your rum. If you mix 2 ounces of water into 2 ounces of 190 proof rum you don’t get 4 ounces of diluted rum, you get about 3.9 ounces. The repudiation of common-sense arithmetic has to do with the different sizes of water and ethanol molecules. Water molecules are bigger so the smaller ethanol fits in the spaces between the water molecules. It’s a little like that old story about the gallon bucket filled with rocks into which you can still pour a half-gallon of sand. You can add the sand to the “full” bucket because the sand goes in the spaces between the rocks.

Incidentally, you can pour a cup or two of rum into the sand-rock mixture. This proves, I’m told, that no matter what, there’s always room for rum.

Sniff

Your sense of smell is a faculty located on two small patches of tissue called the olfactory epithelium, which is located inside your skull behind your nose and at the same level as your eyes. Your smell patch contains some five million receptor cells—about the same number as can be claimed by a mouse. In normal breathing, only 5 to 10 percent of inhaled air reaches this sensory receptor. You can increase the amount of stimulation at the epithelium by a factor of ten simply by using your nose to take sharp, deep sniffs before you drink. Loud nasal honkings that would be inappropriate at the dinner table are in order at a rum tasting. You’ll notice that if you sniff a second time, your impression is diminished, a third attempt and you notice even less—the nose fatigues quickly. Don’t decide if you like the aromas: just try to notice and name them.

The sense of smell conceptualized as something primitive and erotic. Mural in Library of Congress Jefferson Building by Robert Reid.

If you notice aromas—the proper rum word is bouquet—but can’t find the names for them, look at the Short Course in Rum Tasting checklist at the end of this chapter for some hints.

Synesthesia

This is also the time to notice that we humans easily confuse smells with tastes. This is one form of synesthesia, the mushing together or confusion of two separate senses. The evidence suggests that most people are prone to merging taste and smell: in fact, sweet is one of the most common adjectives applied to odors. In one study, 139 people were asked to describe a chemical used as banana flavoring in pastries. Seventy-six of the subjects volunteered that the aroma was sweet, only sixty said it was banana-like and seventy-three reported it was fruit-like. Tests of strawberry and caramel aromas gave similar results.

The folks who study this sort of thing are inclined to think that we learn these associations from them being usually paired—caramel aroma goes with sweet taste, etc. What’s interesting for the rum taster is the fact that deliberately taking this particular hallucination apart leads us to greater awareness of both taste and smell.

So: does the rum smell sweet? Not really, but what aromas remind us of sweetness?

Sip

Swish the rum around in your mouth to get the maximum contact between it and your tongue and also to increase your sense of the bouquet. Keep the rum moving: taste buds get fatigued too. You may enjoy noticing that different sensations are detected in different parts of your mouth and tongue. Remember to notice as much as you can without deciding if you “like” the rum or not.

This is the time to notice how the rum feels in your mouth. Notice how thick or thin the rum seems to feel. This sensation is called body. Thin-bodied rums feel like water or skim milk in the mouth; big bodied rums are more like cream. Rum can also feel smooth or harsh in the mouth. At one extreme is the “hot” punishing experience of rum that’s fresh from the still. At the other is the smooth and rich taste of barrel-aged rum (see the section on barrel aging in chapter 2).

With your mouth full, part your lips a little and draw some air over the rum. Gurgling sounds are permitted. You’ll smell it a second time as the air brings the bouquet around to your “back smell.”

What’s happening here is that airborne molecules reach your olfactory patch through passages in the nose, but they also get there through the mouth and rear nasal passages. Since it is stimulated with the rum in the mouth, the “back smell” can be more powerful and evocative and more like a true experience of flavor.

Swallow or Spit

There’s a part of the sensation of rum that you can only experience by swallowing, but sometimes there’s more rum to be tasted than can be comfortably or sanely drunk. At any tasting where there are more than four or five rums, you will find spittoons or spit cups.

Discreet spitting is a rum taster’s skill, which in itself is worth a little practice. You really don’t want to blow a spray of Mount Gay on yourself or your fellow taster. Pull your cheeks in like a trumpet player, curl your tongue into a groove, and blow the rum out under light pressure.

Pay attention to the aftertaste, or finish. Does it seem like a natural extension of the flavor? How does it feel? Does the flavor last as long as the feeling of heat in the mouth?

Putting It All Together

Tasting isn’t just a matter of taking a rum apart and trying to see how many separate taste points you can discover. You pay attention to individual tastes because all together, they make up the impression of the rum. The situation is not unlike that of the careful listener at an orchestral concert. Attending to separate instruments, the concert-goer nonetheless is experiencing the total harmony of all the sounds, and that, after all, is what the composer had in mind.

So at the end, after the last taste has reverberated its way off your tongue, you’re going to try to grasp the big picture, to “understand” the rum. It may be helpful to think of rum’s harmony in three dimensions:

• Begin with the structure of the rum: its sweetness, astringency, alcohol, acidity, and texture in the mouth. This is an easy place to start because these characteristics are easy to notice.

Taken all together, the elements of structure in a harmonious rum can make a small, subtle impression or a big, powerful one.

• What families of flavors do you notice? Does the rum mostly remind you of fruit? Of flowers? Perhaps you notice spicy, herbal, or earthy and mineral components. Does the front of your tongue detect any sweetness?

• A rum’s structure should complement its flavor and bouquet. We want a big-boned rum to have a penetrating bouquet and a blockbuster flavor, and we want subtle aromas and tastes to go along with a delicate mouth feel. We sense instinctively when one of these three properties is out of proportion.

• Does the rum smell like it tastes? Flavor and bouquet should be similar, both in intensity and character. The rum should seem like a well-balanced whole. Some highly aromatic rums are disappointingly flat or annoyingly harsh in the mouth.

Think of the rum as a cylinder going through your palate from first sniff to finish. You want the rum to be the same size all the way through. By the way, this is also a useful perspective for tasting wine and beer.

• Finally, consider your whole impression of the rum from first look and sniff all the way through to the finish. Imagine it like a story or a symphony with a beginning, middle, and end. Some rums may leave you with a short, peculiar little finish or be all nose, no taste. The best rums tell a good story all the way through.

Vocabulary

You need words to describe all of this. The words are necessary because we can’t conjure up images of smells or tastes without them. It’s a lot like learning to appreciate any profound sensory or artistic experience: we stumble around trying to name what we experience only to find that the names actually help us experience more.

Understandable as the impulse to make up a vocabulary is, rum talk (like wine talk) is still inherently weird. We don’t have a lot of words to describe tastes apart from words that give examples of similar tastes. So:

“It tastes like strawberries.”

“Oh? What do strawberries taste like?”

“Sort of like this.”

This is perfectly circular and takes us nowhere fast, so people reach. If they don’t have words for taste, maybe they can borrow another set of words, and the next thing you know, a rum is being described as “amusing in its impudence but clearly unfocused” or something almost as silly.

But people want to talk about the stuff they drink, and one curious phenomenon helps them do it. The taste of rum creates for some of us a visual and physical impression. It’s easy to say that a rum is “heavy” or “light” and most people will know what you mean. We also seem to understand intuitively the difference between a “big” rum and a “little” one. This isn’t exactly the same thing as the synesthesia we discussed earlier, but it’s not that different either.

A rum in balance suggests roundness, and you hear that word used a lot. You may have already tasted a rum that you found “sharp.” Or perhaps there wasn’t much rum in your rum and you found it “thin,” “stingy,” or “empty.”

Now it’s easy to see how this vocabulary of structure could, in the hands of a playful person, get extended a bit. Let your imagination run and try to imagine the rums that might be described as follows:

“an explosion in the candy factory”

“bewitching”

“short and mean”

“brawny”

“vivacious”

At the end, the final best tasting note is probably a simple “yes” or “no.” Do you want to taste this again or not? In the case of rum, there’s one further refinement: what’s this rum for? (See, A Purist and A Modernist Walk into a Bar.) If the rum is to be enjoyed in a snifter with nothing more than a splash of water and some good conversation, the demands are pretty high: you want elegance and power, you want harmony, a great bouquet, and a long, elegant finish. You may have some other preferences too: some tasters dote on sugarcane, molasses, and caramel, others prefer orange and spice notes.

On the other hand, if you’re thinking about cocktails, then the rum is an ingredient and your job is to harvest the desirable qualities of a rum and add them to your pantry. You may want nothing more than the bite of alcohol or you may want the extra dimensions of spice and cane.

The Taste of the Times

Having your own opinion takes time and work. That’s right—there’s nothing natural about it at all. In the meantime, it’s nice to know that a zillion rum tasters before you have paid thoughtful attention to the matter of quality in rum. As you learn to trust your own taste, it’s nice to know that there’s a current consensus about what makes a good rum.

The consensus is not eternal. It changes slowly with a major fashion cycle about every two hundred years or so. The first rums were probably pretty harsh, their only grace notes coming from the time they spent in the barrels in which they were shipped. The introduction of column stills in 1830 provoked a sudden shift to a taste for more refined spirits. The minor cycles, with shifts in preference for a little more or less sweet or tannin are probably twenty- to thirty-year affairs. That said, here is the grave but slowly changing wisdom of our rum-drinking ancestors:

• A rum should have a well-defined and attractive bouquet. It should remind you that its raw material is sugarcane—not table sugar or brown sugar, but the tall, grassy, fibrous stuff that looks a little like bamboo and tastes a bit like vanilla.

• The body, or sensation of thickness in your mouth, should be proportional to the flavor and aroma; big flavors should have a heavy body, delicate ones a thin body.

• The alcohol should be detectable but not overly intrusive, seductive but not vulgar. We don’t want our booze to be too boozy.

• The finish should linger in your mouth and echo the flavor of the rum. Some authors would say that the finish should remind you of the tropics, of that band of earth twenty degrees north and south of the equator where sugarcane grows. (Of course for many of us, the smell of the tropics involves sunscreen and insect repellant, but let’s try to stay romantic here.)

So what flavors might you look for? Here’s one checklist:

Brown sugar, vanilla, molasses, caramel, fruit, dried fruit (raisin, apricot, prune), cinnamon, spices, nutmeg, tobacco, coconut, toasted coconut, bananas, caramel, honey, chocolate, orange peel, apple, coffee, cocoa, tobacco, sherry, pepper, grass, smoke, toffee, treacle.

Some questions arise:

• When we talk about “taste,” are we really talking about “smell?” Can you think of examples to the contrary?

• Why swirl?

• Isn’t quality just a matter of taste? Is your taste anything more than a product of your times and social circle? What tastes will your great-grandchildren love?

• Is there anything you might learn from tasting rum that would be relevant to the rest of your life?

• What do the concepts of “balance” and “harmony” mean when applied to rum?

* A company that wanted to seize the pole position in the race to market wood-aged rum might benefit from distributing a distinctive stemless snifter with molded indentations for the drinker’s thumb and first two fingers.