CHAPTER 8

FURTHER

RUM

READING (AND TRAVEL)

“I drink because drinking makes it less lonely in here.”

—Emanuel Cardoso

T here is something perverse going on here.

If you tell people that you’re writing a book about a drink, beer let’s say or even rum, the response is almost always a smile. There’s something inherently frivolous about an interest in alcohol, people entertain the suspicion that your “scholarship” is really just a veil over some darker interest or evidence of a lack of the ability to deal with more serious things.

And yet, as I look over the list of books that I consulted as I put this one together, I’m struck by how much top-quality writing and/or scholarship I found. There’s the breezy insouciance of Ian Williams for instance and here’s the thoughtful sophistication of Charles William Taussig. (The same could be said of beer. Michael Jackson, Randy Mosher, and Bill Bryson are all sophisticated voices drawn to an ostensibly plebian or at best frivolous subject.)

There’s “serious” scholarship here too. In spite of occasionally ponderous prose, Sidney Mintz’s Sweetness and Power is a challenging milestone in looking at how the tiny levers of consumption sometimes move the supposedly larger worlds of politics and power. Charlotte Sussman rather cleverly cut to the core in Women and the Politics of Sugar.

Drinking itself and inebriation blissful or demonic have attracted their share of thoughtful and elegant writers. The New York Times itself has assembled an all-star team for the online anthological blog “Proof: Alcohol and American Life.”

So what’s goin’ on here?

Part of the answer is obvious: Many writers drink and find the writing to be better for it. Many drinkers write and don’t have far to look for a subject. To go a step further: most of those writing drinkers and almost all of those drinking writers are also readers. To read good drinking writing, I’m told, is almost as much fun as drinking, so there’s an audience there.

But I suspect that there’s more here than the simple matter of readers taking in each other’s wash.

Then there’s the question of stage fright and self-doubt. Writers rarely see their audiences but are no less afraid of them, and almost everything that can be said about alcohol and courage has been.

Lurking in the background is also the difficult and undeniable fact that drinking and poetry have been connected for as long as they both have existed.

“Wine’s the train the Muse takes into town.”

—Joan Adler

How does that work? How do inebriation and inspiration find each other? How do they do it so frequently? It’s a question that terrifies prohibitionists and writers alike. If in wine there is beauty (as well as truth) then what’s the point of railing against wine? And what sort of person would want to? On the other hand, if all of Dylan Thomas is 32 percent whiskey and 68 percent Thomas, isn’t the writer’s self-esteem and sense of accomplishment on pretty shaky conceptual ground here?

Of course, I raise these questions not to answer them, but simply to call for more. More reading, more writing, and yes, more drinking. Here are a few items that may be worthy of your consideration.

YO-HO-HO AND A BOTTLE OF RUM.

Rum has a legitimate historical connection with piracy and the Caribbean and this little verse isn’t part of it. It was written by Robert Louis Stevenson and published in his 1883 novel Treasure Island. Stevenson only gave us the title and a fragment.

Fifteen men on a dead man’s chest—

Yo ho ho! And a bottle of rum!

Drink and the devil had done for the rest—

Yo ho ho and a bottle of rum.

In spite of this thin-bodied spirit of an origin, the song has been fleshed out and reused in several movie versions of Treasure Island and even as background music for an amusement park ride at the wholesome Disney World. By the way, the Dead Man’s Chest in the title has nothing to do with a dance involving more than two dozen men in a particularly small area. It refers to the custom of auctioning off or raffling the sea chest of a man who died.

Books

Caribbean Rum: A Social and Economic History

The Archaeology of Alcohol and Drinking

by Frederick H. Smith

Caribbean Rum describes the role of rum in the plantation system of the Caribbean since the sixteenth century. Smith is the right man with the right background to place rum in its proper cultural context. This book draws on documentary, archaeological, and ethnographic evidence from Africa, Europe, and the Americas. Contains the best description of the place rum came to have in West African religion and funeral rites. Smith is a solid scholar and a competent writer.

The Archaeology of Alcohol and Drinking is a delight. By focusing on the physical evidence of alcohol’s production and use, it’s especially valuable as a resource for understanding the shift from home to industrial production of alcohol. Smith is willing to overreach his discipline a bit in allowing that sometimes alcohol is nothing more than a temporary relief from the stresses of everyday living.

Mastery, Tyranny, and Desire: Thomas Thistlewood and His Slaves in the Anglo-Jamaican World

by Trevor Burnard

Thomas Thistlewood was an Englishman who emigrated to Jamaica in 1758 and for thirty-six years was a planter, a landowner, and an overseer of slaves. His fourteen thousand page diary details the particulars of that life in details that are both achingly mundane and casually horrifying. If you need to be reminded of Hannah Arendt’s equation of banality and evil: here’s your book. Details of household management in the tropics are interspersed with casual accounts of brutal sadism and both are related with the same flat affect.

Thistlewood routinely punished his slaves with floggings and other grotesque punishments. One of his preferred punishments was the “Derby’s dose” in which a slave would be forced to defecate into another slave’s mouth which would then be forced shut for several hours.

If there is anyone left who would romanticize slave-holding either past or present, this book should be both required reading and sufficient antidote. If the reader can contain her stomach, it also offers some documentation of life of master and slave and the political reality that made slavery and sugar possible.

Rum: A Social and Sociable History of the Real Spirit of 1776

by Ian Williams

Williams is a freelance writer who has adhered to scholarly standards to produce a book with a strong point of view. He maintains that the economic and social role of rum in Colonial America has been systematically suppressed by prohibitionist sentiment and prejudice. He is also unremittingly Anglo-centric, a bizarre take on the cultural world of which we get too little here.

The book is rich in primary sources and it’s an excellent starting point for discovering more about the world of rum.

The Table Comes First by Adam Gopnik

Gopnik is the smartest guy in the room and this funny, far-ranging book is about a great deal more than drinking. One high point of The Table Comes First is the author’s account of taking the writers Mordecai Richtler and Wilfred Sheed out for a monthly drunken lunch.

The Trip to Echo Spring by Olivia Lang

This is an engaging but gloomy book written by a Brit who seems to be more fascinated with American alcoholic writers than with her boozy countrymen. She talks about the role of alcohol in the life and work of John Berryman, Raymond Carver, John Cheever, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Tennessee Williams. She advances the plausible hypothesis that writing and drinking are both attempts to pacify fearsome loneliness. Hemingway’s observation that he drank “to make other people more interesting” isn’t far from Lang’s idea.

The Distillers Guide to Rum by Ian Smiley, Eric Watson and Michael Delevante

Not for the general reader, this book is intended for the person who knows enough about distillation production to at least have fantasized about that fabulous batch of rum or bourbon that they’ll make one day. You would at least have to have brewed a batch of homemade beer to get the most out of it.

The illustrated chapters on the distillation process are the best, and his description of considerations for fermenting the wash are invaluable. You could easily use them and the fermentation recipes provided to produce a batch of rum ready for aging.

The Wet and the Dry: A Drinker’s Journey by Lawrence

Osborne

Osborne is the author of the novel, The Forgiven. He’s also an adventurer, travel writer, and author of the wonderfully voyeuristic Bangkok Days and one of the funniest wine books ever: The Accidental Connoisseur. This is the story of travels in Muslim countries in search of a drink—a trip which offers him a leisurely meditation on drinks and drinking

It’s safe to say that his relationship with alcohol is both intimate and conflicted. He writes “The reasons for hating (alcohol) are all valid. But by the same token, they are not reasons at all. For in the end, alcohol is merely us, a materialization of our own natures.”

The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks by David A. Embury

Embury was a lawyer and a wit. He must have been a delight to drink with and this book, published in 1948, is a milestone in substance as well as style. The Fine Art is notable in its organization of cocktails into two main types: aromatic and sour. Embury categorized ingredients into three categories: “the base, modifying agents, and special flavorings and coloring agents.”

He also laid down what should be an eternal rule for all adult beverages. They should whet the appetite rather than stanch it. So an anathema on sweets, creams, and eggs. His emphasis on lots of ice firmly places him in the modernist camp.

An interesting historical artifact: Embury urges the use of large cocktail glasses—at least 3 ounces! This was a man who survived (and presumably defied) Prohibition. If you have even a trace of the bibliophile in you, try to find the 1948 edition.

Proof: The Science of Booze by Adam Rodgers

This is the book that should be packaged with this one. Rodgers claims to be writing about the science of booze, but he’s also writing the history, culture, lore, and romance of the stuff. If books like Short Course in Rum try to drill down into the depths of a particular spirit, Rodgers tries to lead you up to the mountain for the grand view from horizon to horizon.

The fact that he is both erudite and a graceful writer makes this book an entertainment as well as a delight.

The Buccaneers of America by Alexander Exquemelin

This is the authoritative first-person account of the life and exploits of the maritime outlaws who became known as Buccaneers. It was published in the Netherlands in 1678 as De Americanensche Zeerovers. Particularly enlightening is the story of Henry Morgan, whose namesake is a popular modern rum. Exquemelin knew Morgan and presumably interviewed him. The book damaged Morgan’s reputation (he lived until 1688) and he successfully sued the publishers.

This is not only first-rate reading but it is an early example of maritime history that belongs on every frustrated sailor’s bookshelf.

Websites

The Ministry of Rum: www.ministryofrum.com

The Ministry is an ambitious, humane, and well-constructed website. It has become, over the years, a source for information about rum producers and a conduit for them to reach a public. The artisan distillery movement would have had to invent the Ministry if Edward Hamilton hadn’t. Be sure to check out the interviews in which a curious Hamilton visits various distillers and tastes the rum on camera: the video of him at Zacapa, tasting Ron Zacapa Centenario gives you an idea of how complex and interesting rum can be.

Rum Travel

Anyone who has lived in the Caribbean will be quick to tell you that there are almost as many worlds as there are islands. The British Virgin Islands are a world apart from their American neighbors. Dutch and French islands are closer in some ways to their home countries than to each other. Haiti and the Dominican Republic share a border but not much else.

Among the few slender threads that tie the whole region together, rum is conspicuous. Sugar is now the footnote to the story of the exotic, expanding world of rum. Even islands like St. Croix that no longer raise cane continue to make rum. Some islands in which cane didn’t thrive—St. Eustatius and Curaçao for instance—had good harbors and active trading and so enjoy a centuries-old relationship with rum.

So frankly, all Caribbean tourism is rum tourism. You can barely dine without it. If you are looking for history and culture, they overlap everywhere with rum. Even if you want nothing more than a soul-restoring trop-flop, there’s a good chance that rum will raise its sugary head.

Tourism officials in the Caribbean are well aware of the power of rum as a tourist draw. Although the islands have been largely off the gourmet travelers’ list, rum tours are developing. Check the tourist offices of any of the major rum-producing islands for the availability of tasting tours. By all means, consult your favorite distillery, many of them are awake to the possibility of earning customer loyalty through creative hospitality.

Barbados is learning the value of its rum heritage. This is the last wind-powered sugar mill on the island. Photo by Postdlf.

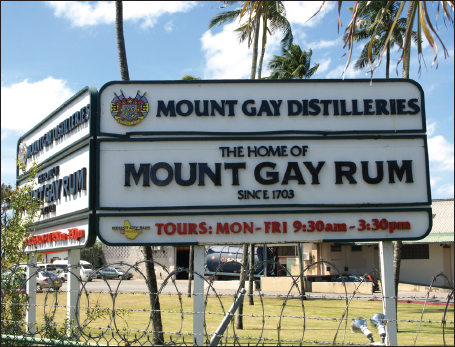

The company was originally owned by a man named John Sober. Tours of the distillery and tasting room are now a major attraction for Barbados. Photo by Captmundo.

The webpage for Cruzan Rum (www.cruzanrum.com) plays on the merging of the rum with the island and its slow-paced way of life.

Rum is made in places like this. Photo by Jason P. Heym/Seascape Pool Center Inc.

Not places like this.