Chapter 2

Soil Formation

Many people throughout the world depend upon soil for their subsistence. Soil is a dynamic feature on the landscape and few realize the importance of the parent rock to soil fertility and productivity. Although the parent rocks determine many soil characteristics, soil is much more than just weathered rock.

Pedogenesis is the term used to describe the formation and development of the soil profile. The "pedon" is the three-dimensional body of soil used as the soil base of reference and "genesis" is often defined as "beginning." Through pedogenic processes the soil profile develops from the very thin—maybe several inches thick which is common in young soils—to soil that is greater than 80 in. (2 m) thick, which is common in older soils.

To understand soil pedogenic processes, it is essential to consider how rocks are formed, how that formation influences their mineralogy, and subsequent breakdown into soil parent material. The minerals in rocks strongly influence the composition of the soil derived from them. The other factors in nature that influence the specific properties of soil in a given location will also be discussed in this chapter.

One of the basic rules of nature is that nothing remains the same over long periods of time. Astronomers tell us that even stars such as our sun have a finite lifespan. They coalesce from cosmic dust, form into shining solar bodies, finally expend their energy, collapse, and return to cosmic dust. The secrets of these processes have only recently been revealed by the Hubble telescope. On earth, the alteration of rocks from one form to another is much more easily understood because we can study specimens of rocks and relate them to their position in the earth's crust.

Rocks are merely combinations of minerals. Minerals have specific chemical compositions whereas a rock refers to a material within a specified range of mineralogical composition that is of appreciable extent in the crust of the earth. Some of the most common rocks are granite, basalt, sandstone, and limestone. Rounded pieces of rock—so common in glaciated regions—are boulders, stones, cobbles, and gravels in descending order of size.

The Rock Cycle

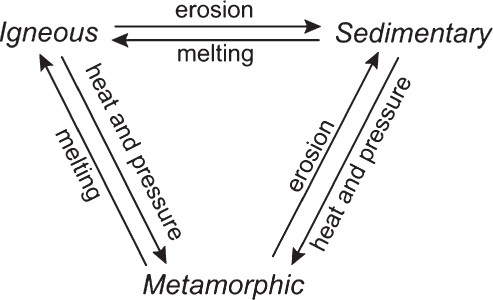

To understand the formation of soil, consider first the rocks from which the mineral particles in the soil were derived. As the earth cooled, the molten magma crystallized into igneous rocks. As long as there has been water on the earth, flowing water has been eroding rocks and the fine particles produced have become sediments, which may solidify into sedimentary rocks. Under conditions of extreme heat and pressure, both igneous and sedimentary rocks may be modified and at least partially recrystallized into metamorphic rocks.

The shifting of continents causes landmasses to slide over and bury other landmasses to the extent that the buried ones may become molten again. Where this occurs there is evidence of great tectonic activity in the form of earthquakes, volcanoes, faults, and related phenomena. Therefore, over geologic time the rocks of the earth are cycled from one form to another (Fig. 2.1). Rocks are the evidence for these actions in the past, and the same processes continue today.

Figure 2.1 The rock cycle shows how heat and pressure, melting and erosion cause rocks to change in form through geologic time.

Composition of the Earth's Crust

Chemists recognize a few over 100 elements that make up everything tangible on earth. Of these, the eight listed in Table 2.1 are the most abundant elements in the earth's crust. The others are no less important, but are present in much smaller quantities.

Table 2.1 Composition of earth's surface crust

| Element | Ion |

| Oxygen | O2– |

| Silicon | Si4+ |

| Aluminum | Al3+ |

| Iron | Fe2+, Fe3+ |

| Calcium | Ca2+ |

| Magnesium | Mg2+ |

| Potassium | K+ |

| Sodium | Na+ |

Silicate Minerals

If molten magma from within the earth cools very rapidly, these elements solidify randomly into a glass such as obsidian, a material commonly used in jewelry. If the cooling is slower, the elements will assemble themselves into crystalline silicate minerals. The slower the cooling is, the larger the crystals.

Silicates are minerals made up, in large measure, of combined silicon and oxygen. They are the most common minerals in rocks. When only silicon and oxygen ions are involved, they form a four-sided structure with oxygen ions at the points and a silicon ion in the center. It can be compared to a three-sided pyramid, with the base being the fourth side. This is called a tetrahedron. If the O2– on each corner is shared with another tetrahedron, a very strong framework structure results. A mineral with this form is quartz, and it is so resistant that it is said to be nonweatherable. Hence, the beaches along our oceans consist mainly of sand.

Of the silicates, most are aluminosilicates; feldspars are the classic example. Feldspars also have a framework structure but from one-fourth to one-half of the Si4+ was replaced with Al3+ during the original crystallization of the feldspar. Since Al3+ has a lower positive charge than Si4+, the unsatisfied negative bonds from the O2– are satisfied primarily by K+ and Ca2+ in the crystal. Feldspars are quite stable but are less resistant to weathering than is quartz. The weathering of feldspar accounts for much of the potassium and calcium found in the soil, the oceans, and sedimentary rocks.

Micas are the other main group of aluminosilicates. The tetrahedra are formed into layers that can be lifted, one from the other, like the pages of a book. When separated from the rocks, these small flat particles will glisten in the sun, especially if they settled out of flowing water and lay flat on the dried soil surface.

Most of the very dark colored minerals in rocks are ferromagnesian silicates. Instead of the framework silicate structure discussed above, these minerals have single, paired, or chained sets of tetrahedra that are bonded together by accessory ions, usually Fe2+ and Mg2+, hence, the term ferromagnesian. It is by way of the accessory ions that weathering gains access to these minerals and the integrity of the mineral structure is destroyed. Two common groups of these dark minerals are the amphiboles and pyroxenes.

Igneous Rocks

Igneous rocks (Fig. 2.2), including granites and their metamorphic associates, make up the bedrock foundation of the continents. The minerals in them are crystalline in form and, if the magma cooled slowly far below the surface of the earth, the crystals are comparatively large. This is the case with granite. If the cooling of the magma took place more rapidly, the crystals are small, such as in rhyolite. Granite and rhyolite may be identical in mineralogical composition and are characterized by having abundant quartz due to the high silica content of the magma. In a parallel manner, magma lower in silica may solidify into very dark colored gabbro or basalt, depending on the rate of cooling.

Figure 2.2 Igneous rocks.

Crystalline igneous rock lays just below the unconsolidated surface material on about one-quarter of the earth's land area. Elsewhere it is more deeply buried. It is quarried for building stones and monuments. Pink and light-colored granite is popular. It outcrops dramatically in the Black Hills of South Dakota at Mount Rushmore, where the heads of four U.S. presidents have been carved. Gabbro can be polished into a beautiful building stone and is sometimes called black granite. A well-known example of it is the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, DC. Blackish and finely crystallized basalt is well known because of extensive volcanic activity on earth.

Sedimentary Rocks

Sedimentary rocks (Fig. 2.3) are the bedrock for about three-quarters of the land area of the earth. These rocks were deposited as loose layers of sediment on the bottoms and edges of ancient seas. Sand, primarily quartz grains, was deposited near the shores, gray siliceous mud farther out, and limy, whitish mud from fossil shells in the deep water. These layers gradually hardened into rock to become sandstone, shale, and limestone, respectively. As the land was slowly uplifted and the seas receded, sedimentary rock covered most of the continents.

Figure 2.3 Sedimentary rocks.

Metamorphic Rocks

Rocks can be altered by heat and pressure within the earth. The metamorphic rocks that result may have been any of the igneous or sedimentary rocks. Granite is commonly metamorphosed into gneiss, a beautifully banded rock wherein like minerals became concentrated due to similar viscosity and density in the shifting magma. Sandstone is cemented by silica from solution to become quartzite, which is the most resistant rock that is widespread on the earth. Shale is converted into slate and limestone into marble by heat and pressure.

Processes of Rock Weathering

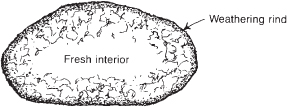

When living organisms such as plants die, they are rotted by saprophytic microorganisms. In a similar manner, naturally occurring physical and chemical forces cause rocks to be weathered into saprolite. Collectively, saprolite is called the regolith of the earth, which is composed of the loose mineral materials above solid bedrock. The effects of rock weathering can be observed by splitting a stone that has been exposed on or near the ground surface for a long time (Fig. 2.4). During the weathering process, the altered rock material may accumulate in place over the solid rock or it may slide, be washed, or be blown to other sites. Soil formation begins soon after loose rock material is stabilized.

Figure 2.4 Exposure to weathering causes tiny cracks to develop in the surface of rocks, which allows for chemical reactions with the penetrating solutions.

Biological Decomposition of Rocks

If you have ever been on a hike into the mountains and sit down on a rock to rest, if you look closely at the rock you will quickly see that it is covered by small macroscopic organisms called lichens. Lichens are composed of an alga and a fungus and are often one of the first organisms to colonize exposed rocks.

Just three years after the island of Krakatoa was largely blown away by a violent volcanic eruption in 1883, scientists visited it and found that the surface of the fresh bedrock was already being invaded by cyanobacteria, one of the most self-supporting forms of life on earth. It can both photosynthesize and fix nitrogen. Growing along with the cyanobacteria were nitrogen- and carbon-fixing bacteria as well as fungi and lichens. Weak acids produced by these microorganisms were dissolving nutrients (phosphorus, calcium, etc.) from the rocks and building up a humic mat capable of supporting mosses and eventually higher plants. The weak acids include carbonic acid formed by solution of carbon dioxide gas in water and lactic acid produced by fungi, and the stronger acids (nitric and sulfuric) were formed by bacteria. Certain fungi and bacteria can release phosphorus from mineral particles. It is evident that microorganisms are involved in rock weathering from the start.

Physical Weathering

Physical weathering of rocks is their breakdown into progressively smaller pieces with no change in molecular arrangement within the minerals. Any of the forces that transport solid particles causes them to wear. Sand on a beach that is rolled by each incoming wave is a familiar example. Strong winds pick up sand and blast it against objects that soon show the effects of abrasion. Tree roots penetrate cracks in rocks and as the roots grow they cause the cracks to expand and eventually break the rock. In temperate regions, water enters cracks in rocks, freezes, and can cause the surface of the rock to peel off like the rind of an orange, which is called exfoliation. Glaciers were the ultimate in physical weathering as they broke loose massive boulders and moved them great distances with a grinding action. Hills were lowered, valleys were filled, and there was a general leveling effect except at the glacier's edge, where small hills called terminal moraines were created. No matter the extent of physical weathering, it does not directly cause significant release of ions from the minerals for the benefit of plants.

Chemical Weathering

Chemical weathering, as the term implies, results from chemical reactions that alter the molecular composition of minerals. These chemical forces react with the surface of minerals. If physical weathering did not greatly increase surface area by breaking down rock into smaller pieces, chemical weathering would progress much more slowly.

Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis is important in mineral weathering. It takes place when hydrogen ions (H+) in water replace metallic ions in minerals. All water is slightly ionized, so hydrolysis is pervasive. Rain absorbs carbon dioxide (CO2) as it falls, resulting in a relatively weak carbonic acid (H2CO3), which greatly increases the reaction of hydrolysis. However, the ancient statues from the Greek and Roman empires did not show much degradation until smoke from modern industry resulted in sulfuric acid and nitric acid in the precipitation. Over millions of years, most of the acid in the soil resulted from the respiration of CO2 by living organisms. Plant roots also release H+ during nutrient uptake.

In one simplified example of hydrolysis, potassium feldspar reacts with water to yield silicic acid and potassium hydroxide as shown in following equation:

The silicic acid is the building block of clay. In the reaction, the primary mineral is destroyed, clay is formed, and potassium (K+) is released into the soil for use by plants. If precipitation is sufficient to leach away the base (KOH), the land will become more acid and the sea will become more basic.

Oxidation

Oxidation takes place when certain multivalent ions lose an electron (a negative charge) to become more positive. A common element in rocks capable of two valence states is iron. Just as a wrench left in the rain will rust, so also iron-bearing minerals in rocks become oxidized. The equations for the reaction are

Hydration

By itself, oxidation would not be extremely disruptive to the mineral, but, in nature, it is followed by hydration:

In this reaction, n water molecules attach themselves to an iron oxide molecule. This results in considerable expansion, which greatly disrupts the mineral structure of the rocks and causes them to crumble. For this reason, when digging in the subsoil in a humid region it is common to encounter stones that disintegrate if struck by a spade. Manganese is another element in minerals that can exist in multivalent ionic states, but it is much less abundant than iron. Salt may also hydrate with similar results.

Reduction

Reduction, being the opposite of oxidation, reflects a gain of electrons in multivalent ions. It is not disruptive to most bedrock, but it does have a marked influence on soil where oxygen has been depleted by microorganisms in wet places. Under reducing conditions, iron and manganese may be dissolved and removed from the system or translocated to regions with free oxygen. Here they precipitate as nodules, concretions, or various types of layers and coatings.

Solution

Water comes as close as anything to a universal solvent. However, it is only capable of dissolving large quantities of soluble salts that were precipitated from solution at some earlier time. The calcium carbonate in limestone came from the shells of sea creatures. It is an example of a salt that is slowly soluble in pure water, but water enriched by carbonic acid, due to biological activity, reacts with limestone. This dissolution is evidenced by massive caves where the rock was dissolved by biologically acidified water that seeped down from the soil.

Factors of Soil Formation

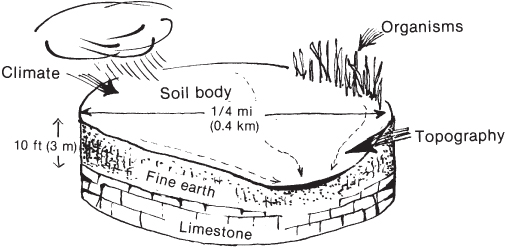

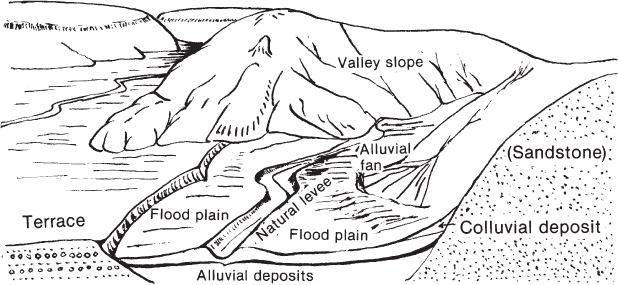

Soil scientists think of soils as natural bodies that have length, breadth, and depth. Each soil body occupies a portion of the landscape. This means that soils are more than simply the product of rock weathering; they are components of the landscape (Fig. 2.5), just as are rivers, forests, marshes, and prairies. Thousands of years have been required to make our present-day soils. Five factors of soil formation have been identified (Fig. 2.6). They are (1) parent material, (2) climate, (3) living organisms, (4) topography, and (5) time.

Figure 2.5 Soils are natural features of the landscape.

Figure 2.6 Parent material in a topographic location is acted on over time by organisms and climate.

Soil Parent Material

Parent material of mineral soils is the weathered rock that was slowly broken up at a site or was transported there by natural agents. It can be grouped into (1) crystalline rocks, such as granite and gneiss, (2) sedimentary rocks, such as sandstone and limestone, and (3) geologically recent deposits, such as alluvium and glacial till.

Soils that have formed from granite contain a full range of particle sizes, from gravel and sand to the finest clay. Since quartz grains (somewhat like bits of glass) in granite are very resistant to weathering, they become the gritty sand in the soil. The less-resistant minerals in rock—such as feldspar (a word meaning field crystal) and dark minerals rich in iron and magnesium (ferromagnesian minerals), including black mica—are altered by weathering into fine clay particles.

Black and dark gray crystalline rocks include gabbro (coarse grained) and basalt (fine grained). Because these rocks contain no quartz, soils formed from gabbro and basalt are not sandy but are clayey, sticky, and rather fertile.

Soils from sandstone are sandy; those from shale are silty or clayey. Soils from limestone consist largely of insoluble shaley materials that were included as gray mud in the otherwise more weatherable rock mass. Therefore, soils from limestone commonly are clayey.

Recent deposits are blankets of geologically young sediments that overlie the types of bedrock just discussed. They include (1) eolian (windblown) sand, (2) loess, (3) volcanic ash, (4) glacial drift, (5) alluvium, (6) and colluvium (Fig. 2.7).

Figure 2.7 Bedrock may be blanketed by sediment from several sources.

Eolian sands are most common in arid and subhumid areas. Most were initially deposited by water when massive expanses of sandstone were being eroded over a long period. Wind action may shift these cover sands into dune formations, which are then referred to as eolian deposits. The Sand Hills of western Nebraska are a good example of eolian deposits. When viewed from an airplane, they are seen as an expanse of crescent-shaped dunes. They are droughty and not very productive for crops or livestock.

Loess is a wind-transported deposit that mainly consists of silt that was derived from the flood plains of rivers that drained the meltwater from glaciers. These silts have a rich supply of plant nutrient-bearing minerals, and their size is such that they hold a significant quantity of water for crops. Extensive areas of fertile agricultural soils can be found in loess deposits in such places as China, the Mississippi-Missouri Valley, and the Danube Valley in Europe.

Volcanic ash is widespread in Hawaii, Oregon, and Washington in the United States and in Central America, Japan, Indonesia, and many other mountainous areas. The mineralogy of volcanic ash is variable, but most of it develops into high-quality soil for crop production.

Glacial deposits, often with a covering of loess, are parent materials of soils in much of the corn belt in North America and the wheat belt of Eurasia. They were left by glaciers (and their meltwaters) that advanced and retreated repeatedly between 1 million and 10,000 years ago. Glaciers carried a lot of rock debris collected by a grinding action on the terrain over which they passed and thus were made of "dirty" ice. An unsorted mixture (till) of stones, sand, silt, and clay was deposited in broad blankets and ridges called moraines. Glacial till is sometimes stony enough to inhibit cultivation, but its fresh supply of minerals provides an abundance of many plant nutrients. Rapidly flowing meltwaters left behind extensive sheets of sand and gravel, called outwash, that tend to be droughty for crops. Where huge ice blocks, which melted later, were surrounded by glacial drift (till and outwash), large pits or potholes were formed. Many lakes once existed near the glaciers. Today, the ancient lake bottoms are almost level farmlands with rich silty and clayey soils.

Alluvium is sediment that was deposited by rivers and streams in valleys throughout the world. Centuries of erosion have created fertile areas of alluvial soils: the Bangkok Plain, the Mekong Delta, the Mississippi Delta, and the vast alluvial plains of China. About one-third of the human population is supported on these fertile flood plains that are rich in topsoil materials brought down from the uplands. Although flooding is a major hazard to humans, buildings, and crops, it is a major agent in depositing soil materials. Alluvial soils are finely layered (stratified) to great depths. Each layer may represent the deposit of a single flood. These soils show marked changes horizontally, from somewhat sandy near riverbanks on natural levees and alluvial fans to clayey and even peaty in remote swampy areas. Older soils with distinct subsoil layers may be found on natural terraces, or "high bottoms," that now stand above the rest of the valley floor but were subject to flooding at one time (Fig. 2.8).

Figure 2.8 Representative land forms.

Colluvium, a gravity-transported deposit at the base of foothills or mountains, moved from above to its present location. Often, as in the case of mudflows, it was in a somewhat fluid state at the time of transport. These deposits are extremely variable in composition but are not geographically extensive. Colluvium includes talus, which consists of chunks of broken rock at the foot of a mountain.

Climate

Every place on earth has climate that can be described based on its many components. The two components that most strongly influence soil formation are precipitation and temperature.

Each of the soil-forming factors interacts with the others, and this is evident with climate. It strongly influences the rate at which rocks are weathered into a loose regolith. It controls the supply of water for physical weathering and determines breakup by freezing and thawing. Climatic change led to the advancement and retreat of glaciers and the resulting glacial till.

It is the effect of climate on chemical weathering that has the greatest influence on the weathering of rocks. Precipitation provides the water necessary for chemical weathering processes and may be sufficient to carry away soluble products, thereby allowing the reaction to continue. Without water, there can be no hydrolysis or hydration. Even oxidation-reduction may be dependent on the quantity of dissolved oxygen. The solution of minerals in certain rocks is dependent on rainfall unless they are adjacent to a body of water.

Temperature has a marked influence on the rate of soil formation. Perhaps the most obvious effect is that which occurs in the temperate zone, where essentially no chemical weathering takes place while the ground is frozen. There is a well-established rule in chemistry that for every 10°C rise in temperature, the rate of chemical reactions increases by a factor of 2–3. For example, the soils of the warmer southern part of the United States are more highly weathered than those in the cooler northern states even where glaciers were not a factor.

The combined influence of precipitation and temperature is probably as important as either one of them individually. If the temperature is cool, water does not evaporate fast, so the effectiveness of the precipitation is high. On the other hand, some warm areas receive quite a lot of precipitation, but due to rapid evaporation, they have the properties of a much drier climate. As an example, St. Paul, Minnesota, and San Antonio, Texas, each receive about 28 in. of precipitation annually, but because of the cool Minnesota temperature, the soil there is normally moist, whereas in the San Antonio area, the soil is usually dry. This effect is also reflected in the native vegetation, which is hardwood forest in the St. Paul area and drought-tolerant vegetation in the prairies of South Texas.

Living Organisms

The influence of all the organisms, plants, and animals (both large and small) is the biotic factor of soil formation. Chapter 4 is devoted to soil biology, but in this section the ways that living organisms are involved in soil development are discussed.

In any particular climatic region, the amount of humus in the soil is a direct result of how much and what type of plant residue has been incorporated into it. Thus, if vegetation is sparse, the soil will be low in humus and less fertile. Grasses have a fibrous root system that quite thoroughly invades the tiny pores of the soil so that as the roots live, die, and decay over thousands of years, the soil becomes well supplied with humus. Tree roots are much larger, but because they do not invade the pores of the topsoil as completely as those of grasses, the humus content of soils under forests is usually lower.

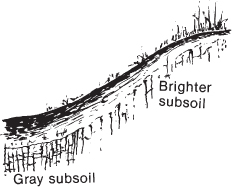

Most of the trees in the world's forests can be divided into two groups: the hardwoods with broad leaves and the softwoods (conifers) with needles. Chemical analyses of broad leaves and needles show that needles are usually more acid because they contain fewer base-forming elements such as calcium and magnesium. Grasses contain even more bases than either broad leaves or needles (Fig. 2.9). Therefore, soils formed under conifer forests tend to be the most acid and least well buffered (e.g., against acid rain).

Figure 2.9 Grass leaves are normally highest in bases, broad leaves of trees are intermediate, and conifer needles are the lowest.

Grassland regions have the most fertile soil for agriculture, but most of them are subject to extended dry periods. Pioneers tended to select the hardwood forests as places to settle because the soils were quite good, and they needed the forest products for their livelihood.

Topography

The lay of the land—its levelness or hilliness—is called topography. Topography influences the formation of soil primarily in two ways: (1) Erosion carries topsoil from the higher positions, particularly the side slopes of hills, and deposits it in the valleys. This results in relatively thicker, more fertile soils in the valleys. (2) Water drains from the uplands to the valleys and if the excess is removed in a timely manner, vegetation is more abundant there. The abundant plant life, which does not decompose as rapidly in moist valleys as on the drier uplands, also contributes to the formation of deep, dark-colored, fertile soils. As a result, much of the world's population relies on crops grown in valleys for their food.

Climatic conditions modify the effects of topography on soil development. In the subhumid and drier climates, the soils are well drained in all positions in the landscape, but they differ in thickness by their long history of erosion or deposition. In the humid regions with a rolling landscape, soils may be thin and excessively drained on the hills and thick with poor drainage in the valleys. Broad, nearly level topographic positions typically have deeply developed soils even if they lie high above the drainageways. In the humid regions, these areas will show the effects of excess moisture unless the parent material is coarse textured, so it will allow rapid internal drainage. In semiarid regions, broad level uplands typically have deep, dark colored soils formed under grassland vegetation.

Topography is a strong indicator of soil characteristics within a particular region. In 1935 an English earth scientist named Milne, working in East Africa, noticed the sequential nature of soils from the top of one hill, down through the valley, up the next hill, and down again repeatedly. Being a scholar in classic languages, Milne knew the Greek term for the arc formed by a chain suspended between two posts. From this, he derived the term catena, meaning a sequence of soils differing from each other due to their topographic position. In a two-dimensional sense, he saw each soil as a link in the chain. A catena is a toposequence of soils that may differ from each other in a variety of ways, such as composition and drainage. The drainage catena relationship of a humid region illustrated in Figure 2.10 is horizontally compressed.

Figure 2.10 In a drainage catena, the soil reflects the effects of long-term moisture conditions.

Time

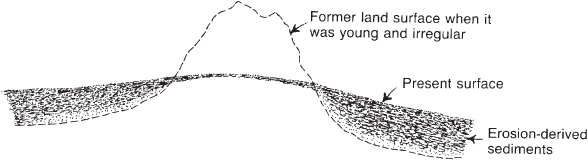

Time is typically discussed as the last of the five soil-forming factors. It is a consideration of how long the other factors have been influencing soil formation. The effects of time can best be seen in equatorial regions, where the extremes in age are well expressed. Geologically young areas typically have an irregular topography, and they are comparatively more fertile because young parent materials usually contain an abundance of weatherable minerals that slowly release plant nutrients as they weather. Geologically old surfaces, on the other hand, have long since lost most of their weatherable minerals. Their fertility is found primarily in the organic matter, which is subject to rapid depletion under cultivation. Since prehistoric times, farmers in the tropics have been attracted to rugged landscapes because of the success of growing better crops there. Similar comparisons of soil fertility could be made between geologically young regions such as the northern Rocky Mountains and old, highly weathered portions of the Piedmont Plateau in the southeastern United States.

In glaciated regions, which occur in much of the northern part of the United States, there is a relationship between the time since the last glacial advance, the irregularity of the landscape, and the degree of soil development as evidenced by the concentration of clay in the subsoil. Regions with more recent glacial till (<25,000 years) have many undrained depressions that may form lakes. Moderate to steep slopes are common, and the leaching of clay to the subsoil is moderate. In regions where the glacial till is much older (>50,000 years), more of the depressions have been filled and a complete drainage pattern has formed. The slopes here are more gentle, and there is usually a much greater concentration of clay leached into the subsoil (Fig. 2.11).

Figure 2.11 Land surfaces tend to become smoother over time as hills are worn down and valleys are filled.

Soil Horizon Development

During soil formation both parent materials and organic materials are altered and translocated so that layers called soil horizons develop. The layers usually can be recognized visually. A cross section of soil horizons, called a soil profile, is exposed when a pit or roadside is excavated. Two profiles are illustrated in Figure 2.12. One is typical of some of the subhumid grasslands and the other depicts the soil of humid hardwood forest regions.

Figure 2.12 The profile on the left illustrates a soil from a subhumid grassland; the one on the right shows a soils from a humid hardwood forest region.

Although the number and properties of these horizons vary widely, a rather typical soil profile in a humid region is discussed in this section. Dark humic materials commonly accumulate in the topsoil (the A horizon), followed by a leached zone (E horizon—from the word eluvial meaning washed out). The subsoil (B horizon) commonly has an accumulation of clay. The depth to the bottom of the B horizon is typically the depth to which there are abundant plant roots and biological activity. Certainly some roots may extend much deeper.

The portion of the soil profile that has been altered by the soil-forming factors is called the solum and is made up of the A, E, and B horizons. On the surface of the A horizon, there may be a layer of plant residue called an O horizon. Below the B horizon the underlying unconsolidated material is called the C horizon. If bedrock is within a few feet of the surface, it is called the R horizon. These symbols may be subdivided with small letters and numbers because of the diverse nature of soil. This system provides symbols used in making detailed soil profile descriptions. The symbols are a type of shorthand used by soil scientists, and they reveal much about the soil properties. The principal soil horizons can be categorized into diagnostic horizons, which will be discussed in Chapter 11.

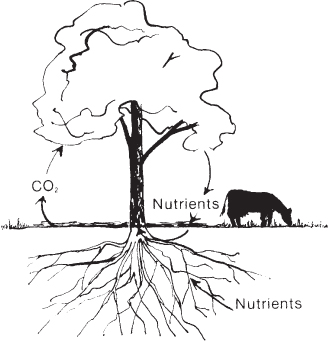

Leaching of plant nutrients such as potassium and calcium takes place as water moves through the soil, but some nutrients are retained by the finely divided humus and clay materials. Plants take up these nutrients and transport them into their aboveground parts. The nutrients are returned to the soil as the seasons progress; thus, plants contribute to nutrient recycling. This biotic cycling helps to keep the soil from becoming infertile by frequent leaching (Fig. 2.13). Weathering is an ongoing process in the soil and to a lesser extent in the substratum below. As soil ages, it is likely to have a higher clay content because clay results from the physical and chemical breakdown of larger particles.

Figure 2.13 Biotic cycling helps to concentrate nutrients near the soil surface.

Let's Take a Trip

As we travel from one climatic region to another, there are distinct changes in the native vegetation, and if the farm fields have been plowed, there are differences in the appearance of the soil, even to the casual observer. If the soil is exposed to some depth, there are even more changes evident to those who examine the subsoil carefully.

If we take a trip in the United States from the deserts of the West to the humid woodlands of the East, a succession of soils could be seen (Fig. 2.14). In the arid regions, the tan-colored soil is only a little darker on the surface than it is deeper down because meager rainfall provides for only sparse vegetation. Even here, however, there are differences. Salts may whiten the soil surface in lower areas if water containing large amounts of salts evaporates off the surface. On very old geologic surfaces, carbonates may accumulate in the subsoil to form rocklike layers. Pebbles scattered on these ancient surfaces are likely to have a dark reddish-brown varnish from oxides of iron and manganese.

Figure 2.14 A trip through different climatic vegetation regions of the United States would reveal many kinds of soil.

As our trip takes us into the central midwestern states, we enter a region where rain is more common during the growing season, and where the native prairie grasses with their abundant fibrous roots have made the topsoil thick, dark, and rich in plant nutrients. These soils do not have a leached E horizon. They are, in the main, the most productive soils in the United States. When fields are plowed, they appear almost black from the abundant humus, and if a road is cut through them, they show that the humus commonly extends 2 or more feet (61 cm) below the surface.

As the average rainfall and humidity increase toward the eastern one-half of the United States, forests replace the grasslands, and the soils are markedly different. When they are tilled, these soils have a grayish-brown appearance, which reflects their lower content of humus and the presence of a leached E horizon beneath a thin A horizon. The subsoil usually has a concentration of clay that shows up as a reddish-brown horizon in road cuts or other exposures. Many of these soils are very productive, but they require more fertilizer and lime because leaching by greater rainfall has occurred.

If we swing south across the Ohio River, we find soils that are geologically much older, and soils in which the effects of weathering have been greater. Here the cultivated fields are quite red in most places as a result of iron from the minerals that have become oxidized. In these soils, the clay-enriched subsoil forms a much thicker zone, and their native fertility is low.

If you travel from southern Texas to northern Minnesota, you will find that soils in Texas will generally have less organic matter than those in the north. In northern Minnesota the growing season is much shorter due to the cold temperature that slows the breakdown or the organic matter. Through time this results in slower soil carbon cycling and an increase in soil organic matter as you move north in the Northern Hemisphere.

Whenever you have the opportunity to travel, be alert to the change in the soils and landscapes. If you look closely you will see that as the soil changes so do the ways people build roads, houses, and manage the land through tillage and crop selection. You will find that some soils can support a lot people whereas other soils cannot.