Chapter 7

Soil Temperature

All plants need sunlight to grow. Light from the sun supplies the energy needed for photosynthesis and also warms the soil and air in which crops grow. Soil temperature affects almost every physical, chemical, and biological activity that occurs in the soil. Management decisions, such as when to plant, are often based on soil temperature. Knowledge of the flow of energy in the soil–plant–atmosphere system helps to understand how plants respond to climate conditions.

Importance of Soil Temperature

Plants

Soil temperature is a greater influencing factor in plant growth rates than above ground air temperatures. Soil temperature influences date of planting, time to germination, and number of days for a crop to mature. Ideal soil temperatures for germination vary depending on the crop and the seed characteristics. Most seeds (provided other conditions are ideal, such as adequate soil moisture) require minimum soil temperatures of 40–60°F (4.5–15.5°C) to germinate. In some cases extreme soil temperature may restrict germination and plant growth and extremely high temperature can cause severe heat stress to young seedlings. Cooler soil temperatures may diminish the ability of the roots to absorb water and nutrients. In normal situations, with increased temperatures, germination and growth of seedlings are enhanced, and root development is faster.

Optimum soil temperatures for plant growth are generally higher for plants that have evolved in warm climates than those evolved in cooler climates. Crops like cotton grow well in warm soil conditions while potatoes, rye, and oats prefer cooler soil conditions. Similarly, different trees have preferences for cooler or warmer soil conditions. In forested areas of the Midwestern United States, a dense oak–hickory–maple forest is found growing in the cooler soils of the north-facing slope, while south-facing slopes (warmer soils) often have a sparse stand of red cedar and burr oak with grass between the trees.

Microorganisms

Microorganisms are vital to the breakdown of plant and animal residues (organic matter) with the resultant release of essential plant nutrients including nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur. Soil temperature influences the growth and activity of microorganisms in the soil. Each organism has an optimum temperature at which its metabolic activity is at its highest level (most rapid breakdown of organic matter). Normal soil temperatures are generally cooler than the optimum for most organisms. As a result any increases in temperature (approaching the optimum temperature) could result in increased microbial activity and faster release of plant nutrients. While warmer soil temperatures can help the beneficial soil organisms, the same is true for the soil organisms responsible for plant diseases. Microbes are also responsible for breakdown of many of the organic wastes and pesticides. Warmer temperatures could help the microbes detoxify a soil faster. Extremes in soil temperature can have a slowing effect on microorganism and plant growth. Extremely high temperatures can destroy pathogenic organisms and weed seeds as is done in composting operations.

Solubility of Minerals

Soil temperature has an influence on the dissolving of minerals by water. Warm water hastens the dissolution of minerals, making nutrients from these minerals available for plant use. High soil temperature and adequate soil moisture mean, in most cases, more nutrients in solution. Soils in climates where rainfall is excessive and soil temperatures are high generally have low nutrient levels because the nutrients from dissolved minerals may have leached out of the root zone.

Soil Moisture

Soil temperature impacts the physical form of water in the soil (ice, liquid, or vapor). The behavior of liquid water is also affected by soil temperature. Temperature has an impact on the density and viscosity of the water, both of which are important in determining the rate of water movement in soil. Warmer temperatures allow faster water movement in a soil.

Extreme soil temperatures could result in frozen water or excessive evaporation losses. A soil with a frozen layer of ice could impede downward movement of water, resulting in ponding of water above the ice layer. Water from spring rains on frozen ground could result in flooding of surrounding low lands due to decreased infiltration and increased surface runoff. In this situation, the surface soil is likely to erode as well.

Water expands upon freezing. Soils containing a (significant) amount of fine particles that can retain water will expand more than coarse textured soils. This expansion could result in internal pressures causing the soil particles to move away from the ice lenses formed during freezing of the soil water. In some areas where perennial crops are planted, pressure caused by freezing could push or lift the plant out of the soil, a phenomenon called frost heave. As a result the plant is pushed upward while the roots remain anchored, causing the roots to break away from the plant, and if the action is severe enough could result in economic losses to a farmer. Similarly, frozen soil conditions can push rocks buried in the soil upward to the soil surface.

Frozen water pockets can put uneven pressures on structures such as roads and shallow foundations, causing the structure to shift/settle in an uneven manner. This is one of the reasons footings that support foundations of buildings are placed at a depth below the frost zone in cold climates. In the higher latitudes, soils may be frozen for longer periods of the year. In far northern regions, the subsoil is always frozen. This condition, which is called permafrost, exists in much of northern Canada, Alaska, and Siberia. In recent years the permafrost has shown rapid melting of the ice layer with serious implications to plants and potentially increased decomposition rates of organic material.

Warmer soil conditions can promote evaporation. As the water vapor escapes the soil surface (drier soil), the heat stored in the water is lost from the soil and therefore it has a cooling effect on the soil. However, inputs of energy could quickly make up the energy lost via vapor with an increase in the temperature of the drier soil. Loss of water due to transpiration can also have the same impact of drying the soil and heating the soil much faster.

Fires

Sometimes extremely high soil temperatures are created by fires. The duration and intensity of the fire will determine soil temperatures and the depth to which the extreme heat is conducted. Extremely high temperature has the ability to burn the organic matter in the soil, resulting in an instant release of plant nutrients. While nutrient release may be a temporary benefit, the loss of organic matter and the destruction of microorganism in the soil may have long-term consequences. High temperature from occasional burning can also result in destruction of weed seeds and pathogenic organisms. However, some seeds that have hard coatings only germinate after being exposed to high temperatures. Sometimes soil temperatures are intentionally raised by the addition of certain chemicals that produce a heat-generating reaction in order to clean up lands contaminated with organic pollutants. The high temperature may cause the organic pollutant to vaporize.

Soil Formation/Classification

Temperature and water play an important role as active soil-forming factors. Solubility of minerals, decomposition of organic matter, moisture conditions, and competitive nature of dominant plants are related to soil temperature. The translocation of soluble materials and their subsequent accumulation in the profile leads to soil horizon differentiation. Soils on south-facing slopes in the Northern Hemisphere will tend to be shallower and contain less organic matter due to the more extreme (warm and dry) climate.

Mean annual soil temperature is generally used to group soils into various thermal regimes. The thermal regime is used for soil classification purposes. The thermal regime of a soil characterizes the type of vegetation that can adapt to the temperature conditions. For example, soils in/on wetlands compared to dry lands and of north-facing slopes versus south-facing slopes could have distinctly different thermal regimes, resulting in distinctly different vegetation and soil properties.

Factors Affecting Energy Inputs

Inputs of energy have a warming effect on soils. The most significant source of thermal energy gain is from solar radiation. The surface of the sun with a temperature of about 10,300°F (5,704°C) radiates energy to the earth. Incidental and sporadic inputs of energy may come from fires, warm rains, warm air masses blowing across the land surface, condensation of dew, biological activity, and similar events.

Atmospheric Conditions

The amount of solar energy reaching the earth's surface will depend on the relative position on earth, season of the year, atmospheric conditions, soil cover (vegetation, snow, or mulch), and other aspects. As energy from the sun radiates toward the earth, it must pass through the earth's atmosphere. On its journey through the atmosphere, solar radiation may not reach the earth's surface because it may be intercepted, absorbed, or reflected by the clouds, various gases, or particulate matter in the atmosphere. Not all of the solar radiation from the sun that reaches the top of the earth's atmosphere reaches the soil surface.

Land Cover

A portion of the solar energy that passes through the earth's atmosphere could be intercepted, absorbed, or reflected by land cover such as vegetation, snow, or mulch. The portion of the solar energy that filters through the land cover and makes it through to the soil surface warms the soil. But only a small portion of the solar radiation actually reaches the land surface and helps to warm the soil.

The type and density of vegetative cover influences how much solar energy reaches the soil surface. A thick crop/forest canopy/turfgrass or layer of snow/mulch shades the soil surface from incoming solar radiation and keeps the soil temperatures cool. In the spring, soils with large amounts of crop residue on the surface warm more slowly than bare soils. Bare soils warm and cool faster than soils that are covered with vegetation or snow. Crop residues or other types of mulch also reduce evaporation. Thus, not only do residues shade the soil, but by limiting evaporation, they also keep the soil moist. A moist soil warms more slowly because it takes more energy to warm water as compared to air in the soil pore spaces. These effects should be considered when modifying management practices after the adoption of minimum tillage practices.

Color of Surface Soil

Solar radiation that reaches the soil surface is either absorbed by the soil or reflected back to the atmosphere depending on soil surface conditions. The term albedo is used to describe the amount of incoming solar radiation that is reflected by a surface. Most soils reflect from 10 to 30% (albedo = 0.1–0.3) of the incoming solar radiation that reaches the soil surface. A light-colored surface will reflect much of this radiation (higher albedo), allowing lesser amounts of energy to be absorbed by the soil. Therefore, dark-colored soil surfaces gain a lot more energy than light-colored surfaces. The same soil will have a higher albedo when it is dry than when it is wet. By comparison, most vegetation reflects more solar radiation back to the atmosphere than soils (albedo = 0.2–0.3).

Slope Aspect

When the sun is directly overhead, its rays strike the soil surface at right angles and more heat is absorbed than when the sun is at a lower angle. The sun is more nearly overhead in the summer, resulting in a high level of energy (heat) absorption. In the fall, winter, and spring months, the sun appears lower in the sky and its rays strike the soil surface at a lower angle, resulting in less heat absorption. These differences are actually due to the absolute surface area over which a given amount of solar radiation is distributed. Obviously, soils that slope toward the sun can intercept more energy and thus be warmer than soils sloping away from the sun. A soil sloping to the south (in the Northern Hemisphere) warms more rapidly in the spring than one sloping to the north. Some specialty crops may be planted on the south side of an east–west row because of the exposure to more direct sunlight. The south side heats relatively rapidly, which speeds germination of seeds by as much as 3–5 days.

Incidental Sources of Energy

Heated air masses may be blown in from one area to another. When the warm air mass is blowing over a cooler soil, there will be energy gains to the soil. Rain or irrigation water that is warmer than the soil can also warm the soil. Biological activity in the upper layers of the soil adds small amounts of heat to the soil. Changes in temperature due to the incidental sources are often not as significant compared to direct solar radiation or fire.

Energy Inputs and Temperature Change

The temperature increase following an input of energy is dependent on the net amount of energy input, the heat capacity of the soil, the amount of heat transferred to the subsoil, and the amount of heat lost to the atmosphere. Energy inputs were discussed earlier in this chapter.

Heat Capacity

Heat capacity is the amount of energy it takes to change the temperature of a material by 1°C. Thus, a material that has a high heat capacity exhibits a smaller change in temperature for the same amount of energy input or energy lost. Each component of the soil (air, water, solids) reacts differently (resultant temperature change) to energy inputs. Among soil components, water has a higher heat capacity than soil solids, and soil solids have a higher heat capacity than soil air. It takes about 3,000 times more energy to warm an equal volume of water as compared to air.

A soil when wet will have a much higher heat capacity than the same soil when dry. Thus, it takes more energy to heat a wet soil than a dry soil. Likewise, wet soils compared to dry soils will show a slower decrease in temperature due to heat loss going from summer to fall to winter seasons. For this reason, wet soils are considered cold soils and they take longer to warm in the spring than dry soils. Thus, planting seeds in a wet soil must be delayed during the spring until the soil warms. Germination is delayed in cold/wet soils as well.

Heat capacities of soils vary depending on the relative proportion of solids, water, and air present. The air and water content of a soil are constantly changing, resulting in a dynamic heat capacity of the soil. Since water has an overwhelming effect on the heat capacity, evaporation, transpiration, irrigation, precipitation events, and drainage can bring about significant changes in the heat capacity of a soil. Therefore, soil moisture is a major factor in controlling the rate of temperature change. With a constant change in the soil moisture content, it makes studying the amount and rate of heat movement complex and difficult to predict.

The bulk density of a soil plays a minor role in altering the heat capacity of a soil. Compacted soils (high density) will have fewer large pores than noncompacted soils (lower density). Dry compacted soils will have a higher heat capacity than noncompacted soils (note: Fig. 7.1 is for soil thermal conductivity). However, for a wet soil, density and porosity play a minor role in altering the heat capacity of the soil.

Figure 7.1 The thermal conductivity of a soil depends on its porosity and wetness.

Heat Transfer in Soils

Thermal energy is transferred as a result of a temperature difference within or between objects. Heat always flows from a warm object to a cooler one. Only the soil surface is subject to inputs of solar energy. Once the energy is absorbed by the soil at the surface, the surface soil is attempting to reach equilibrium with the atmosphere above as well as the subsoil below. As a result, energy in the form of heat is constantly moving at all times in the soil. Subsoil temperature changes are a function of heat transfer in two directions: from the surface soil to the subsoil, and from the subsoil to the atmosphere via the surface soil. Heat can be transferred by radiation, conduction, or convection. All three types of heat transfer take place in the soil–plant–atmosphere system.

Radiation

All objects around us radiate energy in the form of invisible electromagnetic waves (short, intermediate, and long wave lengths). Solar radiation was discussed previously as the primary source of energy input into the soil. The soil surface if warmer than the air above will radiate energy to the air.

Conduction

Heat conduction occurs when energy is transferred from one molecule to an adjacent, cooler molecule. The ability of a material to conduct heat is called its thermal conductivity. Metals such as copper and iron have high thermal conductivities whereas materials such as wood and plastic have low thermal conductivities. The latter are called insulators. The thermal conductivity of a soil depends on the proportion of the soil volume occupied by the solid, liquid, and gaseous phases. While thermal conductance is a measure of the rate of energy movement, the resultant change in temperature is more a function of the heat capacity of the soil.

Most soil minerals have a thermal conductivity about 5 times greater than water, 10 times greater than organic matter, and over 100 times greater than air. A solid rock is able to conduct heat faster than a soil because it has neither air nor water within it. Similarly, a compacted soil or a soil with few pores can conduct heat faster than a noncompacted soil because the compacted soil has more contact between soil particles (Fig. 7.1). When a soil is wet, it has a much higher thermal conductivity than when it is dry because the air in the pore spaces is a poor conductor of heat and thus acts as an insulator. For example, when comparing a wet soil to a dry soil, it takes a lot more heat to raise the temperature of water in a wet soil, although a wet soil is able to rapidly conduct heat.

Convection

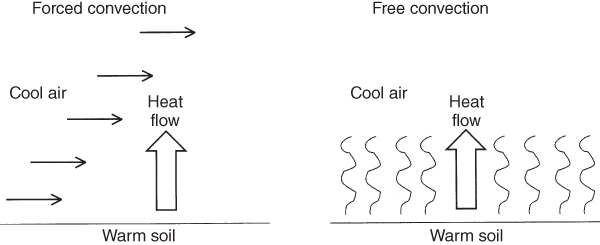

Heat is transferred by convection when the movement of a heated fluid such as air or water is involved. Furnaces that heat buildings by blowing warm air through a system of ducts are sometimes called convection furnaces. Because heat always flows from warmer to cooler objects, heat is transferred from a warm soil to air molecules in a cool wind. Warm air is lighter than cold air, and heat can also be transferred by convection when warm air rises. On spring mornings, sunshine on a dark, bare soil heats the soil surface and the air above it, causing the warm air to rise into the atmosphere by convection (Fig. 7.2).

Figure 7.2 Heat can be transferred from warm soil to cool air by forced or free convection.

Warm spring rains on cold soils could carry enough heat to instantly increase the temperature of a cold soil, but the newly gained soil water has a tendency to slow the increase of soil temperature from future energy inputs. Summer rains can also cool a warm soil. As water is drained out of the shallower parts of the soil profile, the heat stored in the water moves with the water to deeper parts of the subsoil. This kind of subsoil drainage where excess water from the root zone is removed (lower heat capacity) helps the soil warm up faster with renewed solar energy inputs.

Sensible and Latent Heat

Sensible heat is heat energy that is transported by a body that has a temperature higher than its surroundings via conduction, convection, or both. Heat stored in the soil may be transferred to the air just above the soil surface and this heat loss from the soil is considered sensible heat. This situation is typically noticed when going from summer into the fall season as well as after sunset.

Latent heat describes the amount of energy in the form of heat that is required for a material to undergo a change of phase (also known as “change of state”). In the soil, energy used to change ice to water is the latent heat of fusion, and the energy used to convert liquid water to vapor is called the latent heat of vaporization (Fig. 7.3). The energy in the form of heat is utilized when going from solid to liquid to gas, but heat is released when going in the opposite direction.

Figure 7.3 The surface energy budget summarizes heat flow in the soil–plant–atmosphere system. Incoming solar radiation evaporates water, warms the air, and warms the soil that emits long-wave radiation.

Latent heat is simply a shift of energy from one phase of water to another. For example, converting liquid water to vapor involves the transfer of energy from the liquid to vapor phase, resulting in more stored energy in the vapor phase. The stored energy is lost from the soil only when the water vapor is physically removed from the soil by evaporation. The losses of water vapor (drier soil) results in a loss of energy, as a result one would expect cooling of the soil. Instead, a drier soil because of its lower heat capacity can rapidly increase in temperature with any gain in solar radiation.

Condensation of water vapor in the form of dew on the soil surface will release energy stored in the vapor back into the soil as the vapor converts to water. During cool nights, when the leaf surfaces have cooled enough to have water vapor in the air condense on leaf surfaces, the condensed water releases heat to the plant's microenvironment. Prolonged presence of dew on leaf surfaces causes plant pathogens to proliferate.

In temperate regions, the change of seasons from fall to winter could result in freezing of the soil moisture, the freezing process releases heat stored in the water. This heat is lost to the atmosphere, resulting in further cooling of the soil. This concept is utilized by managers of citrus orchards where they spray their trees with water before an anticipated freeze; the subsequent release of heat keeps the leaves and fruit from freezing.

There is an interaction between the latent and sensible heat transfer. When a soil is moist, the latent heat dominates energy transfer from incoming solar radiation (keeping the air above the soil cool). But when the soil dries, the amount of energy used as latent heat decreases and more energy is used to warm the soil solids with a resultant increase in sensible heat, thereby warming the air. If no rain falls for a long period, the crops growing on these dry soils may suffer not only from a lack of moisture but also from excessive heat due to increased sensible heat. Understanding sensible heat flow is important because many crops have an air temperature at which they grow best.

Soil Temperature Fluctuations

The temperature of a soil at a given time is a function of the combined effect of thermal properties of soils, atmospheric conditions, heat transfer, and net stored energy (gains and losses). The dynamic nature of energy fluctuations are reflected in daily and seasonal variations of soil temperature.

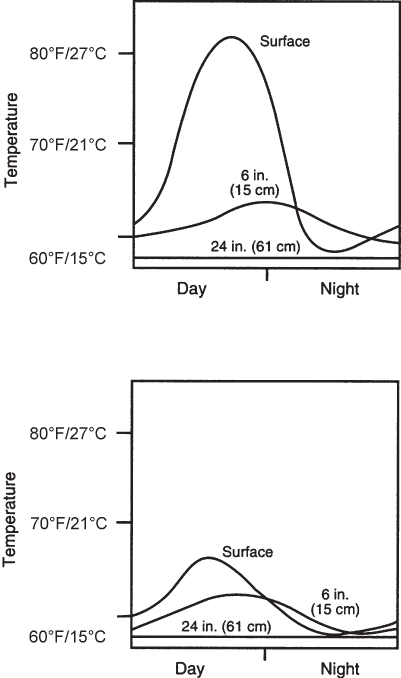

During the day due to incoming solar radiation, the surface soil warms and begins to cool off as the sun sets. The temperature of the soil at the surface is generally slightly warmer than the air above it. At midsummer a soil without vegetative cover may exhibit temperature fluctuations at the surface as much as 40°F (22.2°C) in the course of a day. As the energy must be conducted to the subsoil, the fluctuation in daily temperature is progressively less in deeper sections of the profile. For example, at a depth of 6 in. in the same soil, the variation in temperature in a day may be only 10°F (5.6°C), and at a depth of 24 in. (60 cm) the change in one day would be almost negligible (Fig. 7.4).

Figure 7.4 Variations of surface and subsoil temperatures throughout the day—warming during the day, cooling at night.

Depth is also a factor in the variation of soil temperature over a year. On an annual basis, the highest temperatures in the upper 1 ft (30 cm) of soil are normally reached in late summer, whereas the lowest temperatures come in late winter. At lower depths of 2–4 ft (0.6–1.2 m), high and low temperatures lag behind the surface temperatures by 2–3 months.

Depth-related soil temperatures can range widely during the year depending on which part of the world they are located. Many soils in the temperate region show a range of as much as 60°F (33.3°C). In the spring, more heat goes into the soil during the daytime than goes out at nighttime, and the soil slowly warms from day to day. In the fall, the opposite happens and less heat is conducted into the soil as the days grow shorter and cooler whereas a greater proportion of heat radiates to the atmosphere during the long nights.

Managing Soil Temperature

Since temperature has such a profound effect on the rate of biological processes in the upper few inches of a soil, considerable effort has been put into developing ways to modify the surface energy balance in horticultural and agricultural production. In managing soils for temperature, attempts should be made to create nearly optimum conditions for enhancing plant growth and productivity. Since energy is lost or gained at the soil surface, a majority of the temperature control methods focus on modifying conditions at the soil surface in hopes of restricting or enhancing movement of heat in the desired direction. Another way to manage soil temperature is through the alteration of soil moisture conditions.

Surface Conditions

Tilling the soil and creating a rough surface is likely to lower the albedo and improve heat gain, resulting in increased daytime high temperatures. Because of increased macropores in freshly tilled soils, transmission of heat to the subsoil is slower, and as a result loose, tilled soils will lose much of the heat gained during the day to the atmosphere at night.

Manipulation of the surface albedo has been used to increase and decrease soil temperature. As discussed earlier, planting of vegetation has an ability to shade the soil with foliage increasing the surface albedo and therefore providing a cooling effect on the surface soil. In hot and arid regions, increasing the surface albedo by whitening the surface with a white powder can have a cooling effect on the soil. Conversely, in subarctic regions, soil temperatures have been increased by blackening crop residue to lower the surface albedo. These types of practices are only temporary and relatively expensive so they are only feasible in extreme cases or with high-value crops.

Surface slope aspect can also be modified on a small scale to increase soil temperature (Fig. 7.5). This is especially important at planting time at higher latitudes when cold, wet soils delay emergence and early seedling growth. Tillage operations can be used to create a ridge and furrow geometry in east–west rows. Soil in the ridge will warm faster because it dries more quickly and it absorbs more sunlight on its south-facing slope (in the Northern Hemisphere). Seeds planted into the ridge will germinate and grow faster than if they are planted in flat soil.

Figure 7.5 In the Northern Hemisphere, solar radiation at midday produces the highest temperature on dark soil, but soil temperature is also influenced by several other factors shown here.

Mulches

Mulches applied to the soil surface with the intent of enhancing or restricting heat flow include plastic or paper sheeting; organic by-products (crop residues, leaf litter, wood chips, etc.), and gravel. All these mulches create a water and/or heat barrier at the soil surface. Porous mulches like crop residues and wood chips reduce evaporation by providing a barrier to water vapor. Mulches made of crop residue also have a higher albedo than the underlying soil. Soils under a porous mulch cover will be cooler and moister than bare soils during the growing season. Organic mulches with large particles tend to have a large volume of air between the particles. Since air is a poor conductor of heat, it serves as an insulator and keeps the heat from flowing into or out of the soil.

Clear plastic film mulches not only reduce evaporation, but also increase soil temperature by trapping long-wave radiation under the plastic and/or by decreasing the surface albedo. A dark plastic mulch will absorb more heat from the sun. Plastic mulches are common in horticultural applications where young plants require a warm, moist environment.

Soil Moisture Control

Water regulation may be the most significant temperature control method for soils. Presence of excess water can result in lower than optimum soil temperature. Excess water is common in low-lying areas or poorly drained soils. Since a drier soil will heat faster, attempts to avoid or decrease excess water content of the soil could be helpful in regulating soil temperature. To control excess water in a soil, we can avoid the entry of excess water into the soil (surface drainage) or remove the excess water that has already infiltrated into the soil profile by draining it (subsurface drainage).

Surface drainage involves the modification of land surface slopes so as to create a balance between overland flow (excess water) and the amount of water infiltrating the soil surface. Subsoil drainage requires the placement of drainage tiles/perforated tubing in the subsoil or ditches that will allow the excess water in the soil pores to freely flow into the tile/tubing or ditch. The tubing or ditch is sloped so as to carry away the excess water into a larger receiving body such as a stream. The ideal condition for soil warming is to have enough water to provide rapid heat movement to the subsoil, but not so much water as to slow the increase in soil temperature (due to the high heat capacity of water).

In nature, soil temperatures are influenced by the constantly changing meteorological conditions at the soil–atmosphere interface. External influences such as day or night, summer or winter, cloudy or sunny days, rain events, warm or cold wave events are constantly affecting the temperature of a soil. When factors such as geographic location, vegetative cover, and most importantly soil moisture conditions are added, predicting soil temperature becomes even more complicated and difficult.