How can you run about

two minutes after you are born?

Be a horse, then you can discover

a valley, the taste of a mare’s nipple,

your coat moist with her 3-year-old blood.

In a dream set partly in a horse barn,

greenhouse, outdoors classroom, I thought

universe after universe is not here,

is out there, out there, there, there, there,

still going. . .

Here and a rose are within my reach,

visible without wise instruments.

Our earth and sun don’t matter an onion

to dark matter, places without address.

Justice is not done in the universe,

where the only evidence admissible is invisible

or with sweet deceiving countenance.

If all the world’s a stage, the players have stage fright.

Ding dong, the final doorbell is ringing.

(In Middle Scottish “ding” means worthy.)

Mr. Trouble won’t take his finger off

the button. I’m here, unmetaphorical.

No friend or Eurydice is like any other,

lost friends sometimes come as visitations.

Still I take up with string theory

or the rose-by-any-other-rose theory

that holds water.

A bee flew into a rose,

found darkness and silence there,

flew into another rose and another,

then bang, fires, everything.

Gravity and darkness are not dreary.

Mathematicians are heroes

who give meaning to numbers,

a wilderness of zeroes.

The thing about the cosmos

is what we cannot see is beautiful.

Not I, you and me is what I want to say.

My calling card is the periodic table.

I am thorium, the 90th element,

silvery and black.

Protons, the cosmos, black holes,

white dwarfs are never gross.

Soon after the invention of the present tense

there was comparative and superlative,

so off we went to war. We breathe in and out:

the simple past came just like that.

We believed, needed to pray, invented talk,

writing to keep accounts,

although greeting by smelling, whining,

crying, howling, served us well.

We could say please, thank you, good morning

and good night, I love you, without a word.

A child asked me a question: “Back at the start,

bang! cruel, kind, or no heart?”

Among family photos,

a school of smiling rainbow trout.

A magician uncle explained:

they swam across the ocean

although they were freshwater fish,

not saltwater fish. Our good fish family

studied hard underwater and learned

the scrolls, the shelves, the sudden drops.

They were taught to watch out

for sturgeon, salmon, striped bass

coming up river, some to die,

others laid eggs, then returned to the ocean.

My cousin looked for an underwater Bible

in the lily pads but never found it,

saw turtles as big as automobile tires,

but he kept looking, breaking water for heaven’s sake.

Lucky he had eyes that saw in a full circle

not just straight ahead, so he did better.

They had a Watchman fish, an old fish,

too old to fertilize eggs,

every scale thick as a windscreen.

He watched for lone fish returning from war.

Somehow they became human.

They would rather be buried

than thrown overboard into any puddle.

Whatever the season

I add and subtract days and weeks.

I was with my dogs in the park,

I met Monsieur Troublé,

“Mr. Trouble,” laughing.

“What are you laughing at?” I asked.

He spake thus: “I’ve read you.

I grant every birth is a nativity, holy.

Love, perhaps simply befriending,

is the answer in a world

where looking at something changes it.

Yes, eyes change the world.”

“No, no,” a passing angel said, “Ave Maria

gratia plena, Dominus tecum—

words in the Virgin’s ear gave her a Son.”

I said, “Then the nose, smelling changes the world.

Tasting, barely touching or lovemaking changes the world.”

“Nobody is speaking for the ocean,” Mr. Trouble said.

I offered: Moonlight is the traveler

and there was a full moon—

moon, mothered by winter, mothered by spring.

Day goes where night was,

after a long time I go about as music—

let’s say that’s what the good life is,

carrying a tune.

Moonlight sees what daylight does.

“Monkey sees,” Mr. Trouble said.

“Nobody is speaking for the ocean.”

May 19th, a sleepless night,

thirty-six years after the ocean stopped swimming,

I didn’t light a candle. I wrote a letter

to my mother, put a daisy in an envelope,

mailed it express, addressed “to far places.”

The letter came back Return to sender.

Nobody is speaking for the ocean.

I thought my mother was half ocean.

Far back as I remember,

I saw my naked mother,

the ocean swimming endlessly, wonder full.

I did not know the Chinese say “woman is half the sky”;

I thought my mother half ocean, half firmament.

I was born too big. From time to time

I overheard whispering, I had injured my mother “for life.”

They did not blame me. Still, my birth was a sin

like no other. It prisoned me.

I wished I was born from an egg like a pigeon.

I could not say “I’m sorry”

for what I was not allowed to know.

I believed my sin belonged only to me—

not one of the look-alikes forbidden by commandments.

I heard of penance, mine was simply crying.

At nine, I wanted to be a farmer.

I marveled at planting seeds, watching

things grow, and I wanted to be a priest

so I could hear confession, secret stories.

I could do nothing right.

To kiss was to make it “all better.”

I was not a child walking in sand

with a pail and shovel looking out

at the swimming ocean. On the island of Rhodes,

on a Hellenistic street the Colossus protected,

after a Greek revolution, in a celebration

I was shot in the leg by a ricocheting bullet.

The caryatids taught me beauty without saying a word.

I swallowed the Acropolis,

a kind of Eucharist.

It never passed through my intestines.

Even so, life was an apparatus belonging to the city.

Life cleared streets, plowed snow, collected garbage,

was related to an ambulance, elevated trains.

It only made sense when I saw a field of wildflowers,

what some call the hand of God.

It took time before I took my time

reaching for what really was, is.

What is not still is

my more than occasional companion.

The truth is I don’t know the days of the week.

I can’t tell time.

I have lived a summer,

a fall, a winter, an April, a May,

which I say because words are put in my mouth

because you-know-who is trying to sell something.

My mother rocks me to sleep, singing

a Chinese lullaby about crickets playing.

It’s not easy to know so little,

but I wake to wonder, I touch wonder,

I play with wonder.

I smile at wonder.

I cry when wonder is taken from me.

TO ALEXANDER WHO WANTS TO BE A

COSMOLOGIST

September 27th and 28th, two dark rainy days.

Alex was shivering, crying for no reason.

Embraced, he sobbed. It was for lack of summer.

He thought summer was longer.

“It’s cold. It’s already autumn.”

I told him, “You simply must learn to love

autumn, winter, and spring.

We are all star children, made of the stuff of stars.

Don’t cry, we are living in the golden age of stars.”

TO ALEXANDER FU ON HIS BEGINNING AND 13TH

BIRTHDAY

Cut from your mother, there was a first heartache,

a loneliness before your first peek

at the world, your mother’s hand was a comb

for your proud hair, fresh from the womb—

born at night, you and moonlight tipped the scale

a 6lb 8oz miracle,

a sky-kicking son

born to Chinese obligation

but already American.

You were a human flower, a pink carnation.

You were not fed by sunlight and rain.

You sucked the wise milk of Han.

Your first stop, the Riverdale station,

a stuffed lion and meditation.

Out of PS 24, you will become

a full Alexander moon over the trees

before you’re done. It would not please

your mother to have a moon god for a son.

She would prefer you had the grace

to be mortal, to make the world a better place.

There is a lesson in your grandmother’s face:

do not forget the Way

of your ancestors. Make a wise wish

on your 13th birthday, seize the day

from history and geography.

If you lead, you will not lose the Way,

in your family’s good company

where wisdom is common as a sunfish,

protected from poisonous snakes by calligraphy:

paintings of many as the few, the few as many.

You already dine on a gluten-free dish

of some dead old King’s English.

In your heart, keep Fu

before Alexander and do

unto others as you would have others do

unto you.

Brayed at, with an equine kiss

I’ve been told by my much-loved donkey

this is the Chinese Year of the Monkey,

twelve months of spring,

election lights for sale:

I fly with a broken left wing

while males and females have me by the tail.

I am an old fledgling.

Every day is precious, very dear,

I celebrate the new year

last year and next year.

“I wish I was two dogs, then I could play with me.”

I am King and Queeny,

I could chase two red squirrels up a tree,

rule a kingdom on my bed,

play very alive and very dead,

question and answer, fog and dialogue,

play good dog, bad dog,

on a hot summer day

swim in and out

of a river all day,

get wetter and wetter

because R is the dog’s letter,

bark and laugh

with bull, cow, and calf,

answer a moo with bark bark,

have sweet company in the dark,

play two St. Bernards in the snow,

two Chihuahuas in Mexico,

a Bloodhound and Labrador,

till Papa, hands on hips,

says, Quiet! Quiet!, stands at the door

while I, with my two tongues, lick my lips.

I like dog biscuits, fish and chips.

I could go to bed late and early,

I could eat a bone, one, two, three,

and never be lonely,never be lonely.

Lovers of birthdays,

he had 99 years.

The usual toast, “a hundred years!”

would be a curse

so they gave him

a basket of Georgia peaches,

the gift of a photo:

a woman reclining naked,

her tongue showing a little,

a handkerchief, with her hair,

body odor and breath.

He and his guests

will celebrate his birthday

until there are no birthdays

anymore. Lovers of birthdays,

may circumstance, fate

bring him and you

a happier love-death

than an ancient death I recall:

Achilles, his face masked

behind a copper helmet,

slays Penthesilea,

Queen of the Amazons,

as she dies, they fall in love . . .

Lovers of birthdays,

honest readers,

there are a few

who believe her death

the best death you can have.

I’ve been spit at, marching for a cause,

heard shouts, “We know who you are!” from the mob,

but I haven’t done or said anything for years

worth being spit at.

I keep away from places where

if I just stood, looking as I do,

I could find spit and my killer.

I’ve been spit at by snakes,

grasshoppers and alpacas.

I know spit stories.

Jesus spit on mud and cured a blind man.

I heard a Welsh poet say to a Scots poet,

“I’d spit in your eye,

but there’s so much spit there already

it wouldn’t fit.” Enough. Out of their spit

Egyptian gods made children,

while Saturn ate and spit out his sons,

we needed Eden and a virgin birth. Naked

Eve ate the mouthwatering fruit of knowledge—

mortality came with spit.

*

Spit is sometimes sad,

omnipresent, it is kept out of mind—

there’s so much poetry of the senses,

does spit want to be a tear?

Spit was not made to lick postage stamps,

but without spit we die screaming

from a cracked mouth full of death.

It shows family history, has quality.

No doubt, you can get a good price

for a flask or handkerchief of royal slaver—

the proceeds given to charity.

Yes, spit anywhere can be sexual—

everything depends on the mouth.

If you can’t take a little dog spit,

stay out of my house.

*

I did not spit in the face of John Donne.

When the yellow wind is blowing,

a Chinese poet would value Godly spit,

its rhymes and half-rhymes.

We don’t have calligraphy,

but we have spitting images,

a likeness in a cradle, a little face

of a grandmother long dead.

Spit was not made for a spittoon,

but it likes to mingle in a crowd.

Spit doesn’t have a song:

spit is like the morning dew,

it would be happy in a brook.

All water is made by God who took

ocean, mud and bones,

made Muslim, Christian, and Jew.

Now spit has a tune.

I want to spit to the sun and moon,

above the clouds, higher than hawks fly.

Sun and moon take spit as a compliment,

a new star. They have seen everything,

fires that gossip and sing,

how Gods can reproduce Goddesses—

Venus born out of the thigh of Zeus,

but no one has ever tried to spit so high.

“Whoever shall say thou fool shall be in danger of hellfire.”

–Matthew 5:22

Thou fool! Three score and six years ago,

I woke after a fool’s daydream—

I received a pictureless postcard special delivery

from a former girlfriend in Woman’s Hospital

telling me she brought forth a daughter,

her name and weight—I suppose, pride of her husband

of 7 months, a good doctor. I saved the postcard

during years of Reconstruction, pinned to the wall—

my bedroom was full of daughters without fathers.

Sixty years later, on the internet, a blessed event:

I saw a photo of the worthy doctor husband

dancing happily with his daughter,

the picture of my mother.

I saw online she was a piano tuner,

a profession of gifted souls.

Clearly she had love for her happy stepfather.

She’s childless, I do not know with whom she sleeps,

lover, husband, wife, dog, or cat,

or just Eine Kleine Nachtmusik.

She knows middle C from a hole in the ground,

no reason for her to know the mysterious ocean.

My father used to ask me who was I to think,

but I think she has a meantone temperament. Bless her,

she knows Pythagorean tuning, preludes and fugues

written in all 24 major and minor keys.

May she avoid the unpleasant wolf interval.

The child, mother to the man, taught me

fifths, fourths, thirds, both major and minor,

often in an ascending or descending pattern,

the beat, frequencies between notes,

then, of course, the psychoacoustic affect.

My overused ears tend to perceive

the higher notes as flat, compared to those at midrange.

I bought myself a tuning fork for Father’s Day.

I think I’ll go swimming, look under water

for a fathered and un-fathered daughter.

At 65, would it be better for her to know

which father is her father?

Could I explain the look on her mother’s face

when her mother sometimes looked

for the Jew and poet in her Christian daughter?

Would my daughter play on her baby grand

the Great Deception Waltz

if out of terrible curiosity I told her the truth?

Anything is the same old anything. I’ve become part of the thingness

of all things I see: for example, I am partly chair and table.

Moonless, the night seems almost as it was last moonless night.

I let my shirt, my good old shirt, lie quietly on my chair.

Not trained in any religion, I’ve become the thingness I see.

Angered, I have no saint.

I don’t want to be awakened by Christian bells

or called to prayer by first light, when you can distinguish

a white from black thread. The sound of a ram’s horn

does not call me to synagogue. I throw kisses at an elephant God

and a God of preservation. Let me be awakened by a dream—

I’m on a ship, torn open in a fog, a jolted passenger,

awake to the everyday. I sing of the universal,

the thingness of all things I see.

Trees and flowers elbow their neighbors

out of sunlight and rain.

Born misdirected, to better myself,

I made an “In God We Trust” soup

out of vegetable pickings, not killings,

against the recipe: devour one another

to stay alive. In another universe

God may have corrected His mistakes.

I give Him, Her, Them the benefit of doubts.

I would steal, if I had to, His gifts of fire,

air and water. I no longer take for granted

the spectacular inventions, birth and ignorance,

the failed experiment: death.

I could forget this palaver, blame it all on bang,

unbuttoned chance, personal pronouns.

How did we come to be us, the swarm, the packs,

snakes like years wrapped around each other?

Do all living things celebrate Good Fridays,

holy and unholy days and nights,

a certain thoughtfulness, like two nipples

for twins, eight for puppies and foxes?

Is love a good name for all this?

If not—any word.

Now, for a long dead Australian I love,

Bertie Whiting, I will consider

the just-born kangaroo: life-size earthworm

with almost legs dropped to the ground, blind “ joey,”

alone in the universe, makes its way up Mama’s leg

into her sack to suck—later, it jumps out,

grazes on its own half an hour—

a touch of fear,

first joy of coming back after being alone.

(A newborn Einstein on the ground,

given E=mc2, could not, on his own,

make his way to his mother’s tit.)

After a consistent 235 days,

the joey leaves the pouch forever,

whispers in kangaroo, “Mama, I’ll never forget you.”

In the world’s boat, everything that is or was

causes me to praise and curse.

Praise plus curse divided by two

equals silence, not prayer.

Three years ago, dying, in pain,

you told me to my face—“Life everlasting

is to be loved at the moment of death.”

To cheer up this gathering, I recall

a fight you had with your lover husband

who said in rage, “If you go to California

I won’t water your plants.”

Elia, you Turkish Greek Ladino beauty,

all your life you served Dionysus

in the theater and unholy places.

He had power to protect you.

Where was the God of the grape harvest,

the theater and ritual madness,

when the laborers kept sweeping your cancer

and rotten blood as if cleaning a gutter,

tangled hoses, tubes in all your woman holes

and subway tracks? You kept your smile

with all its colors, as if you were a bug

in a bottle of formaldehyde at the hospital or studio

that once smelled of oil paints, linseed oil,

turpentine, and the perfumes you and Sappho

used a touch of in certain places.

There is still hope of deathly justice,

perhaps, perhaps, perhaps

an angel will come with a harp and sing,

the harp itself beautiful as the Brooklyn Bridge,

and flower pots on New York City roofs

your lover painted. An unknown psalm

in Hebrew in parallel rhymes:

O Elia, my Elia

your life was reason for the Lord, Ancient of Days,

with his 42 names to give thanks and praise.

*

Lord or not Lord, Monsieur Descartes,

silence is a sound that establishes your heart.

You made noise for the Lord,

noise is sometimes right, sometimes wrong,

war songs and love songs—

peace comes with a governance of good and evil

independent of Paradise or Hell.

Who in New York or Istanbul will deny the possibility

that a wind God, purple eagle,

will come and carry you off,

lift your body out of an oak crate,

its American dirt, its amphora,

carry you to the ancient olive trees of Smyrna.

Male or female, he will do unto you what Gods do.

We all become dust and morning dew

blown away from here to there

out there—how far? Take any number

and add a mile of zeros.

We are not resurrected, we are misdirected.

We will stand on stage again,

the congregation in the pit.

The play is called Nothing.

Sooner or later you, all of us,

have a second death—we are warned

like Cordelia, “Nothing will come of nothing.”

Wouldn’t it be nice if in the end we married France?

O star of many wonders,

“always, always, always, always.”

I forgot to say, to death there is no consolation.

GARDENS AND UNPUNCTUATED POETRY

Gardens do not need punctuation

between the lavender and peonies

baby’s breath and violets

commas do not offer anything to morning glories

or devil’s paintbrush or roses

the way the world is made

fragrant scarlet orchids and sweet peas

are not in apposition

the thought that gardens should have semicolons

or colons silly as street signs in a garden

Stop No Left Turn Dead End

Save hydrangeas from the parenthesis

the gardens of Grenada from upside down question marks

save anemones from the circumflex

the Dutch tulip from the umlaut

may Apollo protect a thousand palm trees

from a single exclamation mark

the amaryllis from the em dash

even now an Irish wart from a Roman nose

Palm trees and poems under the sky

do not need further clarification

certainly there are borders and caesuras

in poems gardens and dooryards

we see the mass slaughter of living things

there are stops worse than punctuation

some may choose to read an ancient garden

from right to left

or as a field that is plowed from the bottom of a page to the top

reading a garden or a poem depends on the reader’s

need to praise or to live near flowers and certain words

he or she may want to linger a while

on a surprising verb or lily

I cheer for the first crocus pushing through the snow

proof to many God keeps his flowers and his word

I have seen fields of cornflowers and poppies

all the life they hold cut in two

by railroad tracks highways billboards oil fields

coal mines shopping centers and motels

things worse than punctuation

because the ocean was once where the garden and valley is

perhaps the reason the potato has a purple flower

the reason fish know the dances of India and Andalusia

why a gardener has written a poem about the word the

somehow left behind by the retreating tides

I have found gardeners on their knees

and farm workers laboring in the scorching sun

no less reverent than praying nuns

sometimes the world intrudes on gardening

poetry and punctuation

on a scorching August day a black field-hand

from my neighbor’s potato field

knocked on my air-conditioned purple door

I found his distress frightening

why was he suffering like a wounded soldier

entering my life knocking on my door

when there was no war nearby

in terrible pain he said something like got a beer

I gave him lemonade and a wet towel

little or no comfort

something like punctuation

A clothesline

tied from a dead ash to a weeping willow,

my old and new clothes washed clean,

on close look not washed, something to fool the eye,

my stained underwear and holy socks,

blooms of good and evil, and something to fool the ear,

dirty laundry flapping in the wind in meter.

I know bird chatterings are love calls,

“Rr” is the dog’s letter.

Why don’t they teach the “are”s anymore,

you are, we are, what are we to do?

Clothespinned to the line, my dirty laundry

often tells the truth, not the whole truth,

not nothing but the truth, so help me God.

Laundry makes nothing happen: it survives

in the valley of never-fooled sun and winds

where nothing is said by happenstance.

I babble, trying to honor the language:

“I am the world, a globe walking with long legs,

cities, oceans, smoking dumps around my waist.”

When the music changes, the fiber optic lines tremble.

I hum the rest, I remember poets who made it new,

swam in the Yangtze, Passaic, Thames and Charles.

Like Hart Crane I wore a bathing suit with a top.

I thought describing the fat lady in the circus,

legs spread apart from the ankles up,

was the naked truth. Why are there no laughing willows?

There are giggling brooks. I heard laughter in the forest,

seven foot golden bantam corn growing in August.

It sounds like happiness, till 8 p.m. above the Hudson,

when laundry, clean and dirty, is taken in,

when the night creatures I love come out.

Forty years ago, I wrote I would sooner disgust you than ask for your compassion. My tears are barley water. I give you my tears to wash your feet. My tears are lace on my father’s face. My tears are old rags that do not fit me. My tears are spit on my face, I know spit is sexual. My tears mean no more to me than my grocery bill. My tears are produce I stand in line for. Crying makes me a child, female, shows I am a man speechless about love. I would sooner hold a porcupine than defend tears. My dogs may pull it to pieces, get a mouthful of quills . . . it’s too lonely. I can’t take care of it. I begin to feel the wish to kill—the thing is dangerous. I don’t know what it eats. (A porcupine is the other animal that cries with tears.) I cover my eyes with my hands. I have betrayed the impossible, my porcupine—the thing’s alive, smells of urine. I look for gills, see ears, I feel the weight of thorns and flesh, Christ’s crown. I went into the woods that know me. The trees remembered my mother. Wildflowers taught me reality is just what is. The leaves set an example of representative democracy. The wind taught me chants and common prayer. The sunflower taught responsiveness, the dew punctuality. Oh my teachers, where did I ever learn my vices? Walking with you in the woods I learnt lust. Your lips taught me to be lazy. Your eyes taught me greed. Your touch to lie. You have burned my woods . . . cut down trees, left me only with a snake, the penalty for all those who search for paradise . . .

He painted his faults,

what he could not see clearly,

he was the better for it.

He painted the unlikely,

the un of things:

unhappy, unforeseen

the uneventful everyday,

an abstract all or the everything, the fibs

“breath poor and speech unable”

the circle and straight lines

of what he called always

the ABCs of never.

He dressed without thinking about the weather,

what colors go with, dandy or maudit.

In the lift, by mistake, he nudged his neighbor

he barely knew. His hand too high,

he waved as if from across the street.

He washed his brushes

in turpentine, the sink became

a gorge of sunrise and sunset.

Friends phoned,

he answered, “Pronto,”

“Dígame,” “Oui,”

on a party line,

the Coney Island of telephones.

He was proud his callers heard from one word

his preferences, he was a rubble king.

Ninety years after he was given light,

an after-dinner drunk, one time or another—Strega,

Chartreuse, Anís de Chinchón, calvados, grappa—

he could not remember

when he did not hear the knocking at the gate,

sleepless on port

he played the porter in Macbeth.

He said with his loaded brushes, he painted error,

impossible arguments—although they were studies,

his paintings taught

the mountains and deserts of hatred:

the Himalayas Atlas Alps Pyrenees, lost souls,

the Gobi Sinai and Sahara, to love their neighbors—

green valleys were children.

He was a citizen of mythos,

a migrant from the cosmos,

not part of the retinue of chaos.

He could no longer draw a circle.

One Sunday morning,

faulted, almost blind,

he wrote a letter in large script

that went up and down hill:

“. . . my darling, I can still paint what I think,

blind eagles and dumb gossips,

differences between fault, sin, mistake,

the unlikely less likely, the un of things,

a few remembered faces,

the anatomy of my melancholy,

dung and scat, the Dead Sea,

Chinese bridges that are also temples.

I paint changing seasons, what I don’t have words for,

because no two things happen at once.

A few painters said it all,

almost all, others have their right to pleasures

every horse’s ass has a right to.

Kisses for good measure.”

I saw the serpent in the garden

when I was two or three,

the bone of my head still hardening.

I walked with my father who held my hand

crossing Liberty Avenue,

talking over my head

he recited Shakespeare: tragical-comical

historical-pastoral-Samuel.

He was learning lines

he needed for an exam.

I remember my feelings, not the words.

Some forty years later, he thanked me

for the Shakespeare he remembered.

I said no, it was I who owed the debt,

kissed him without regret.

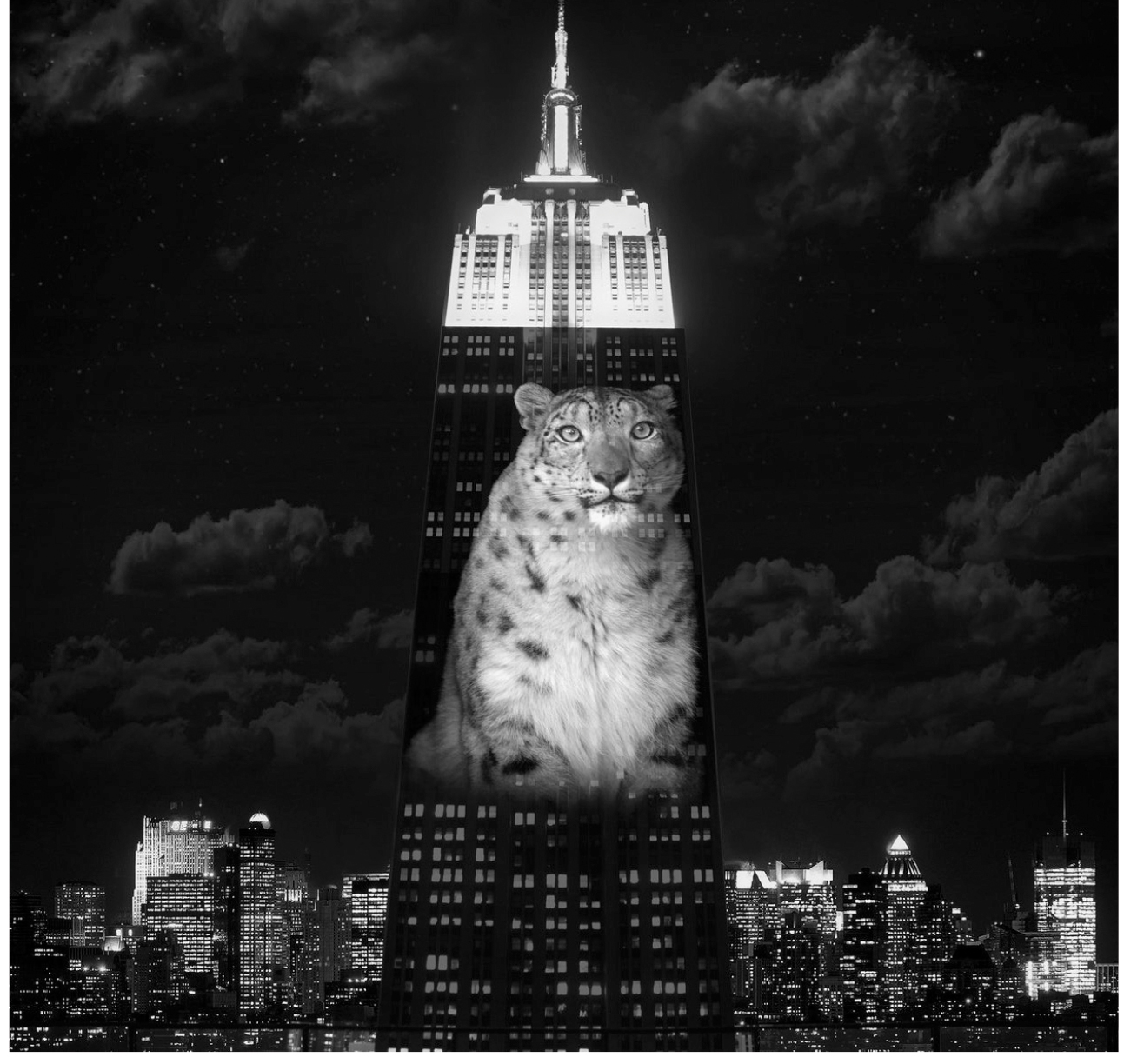

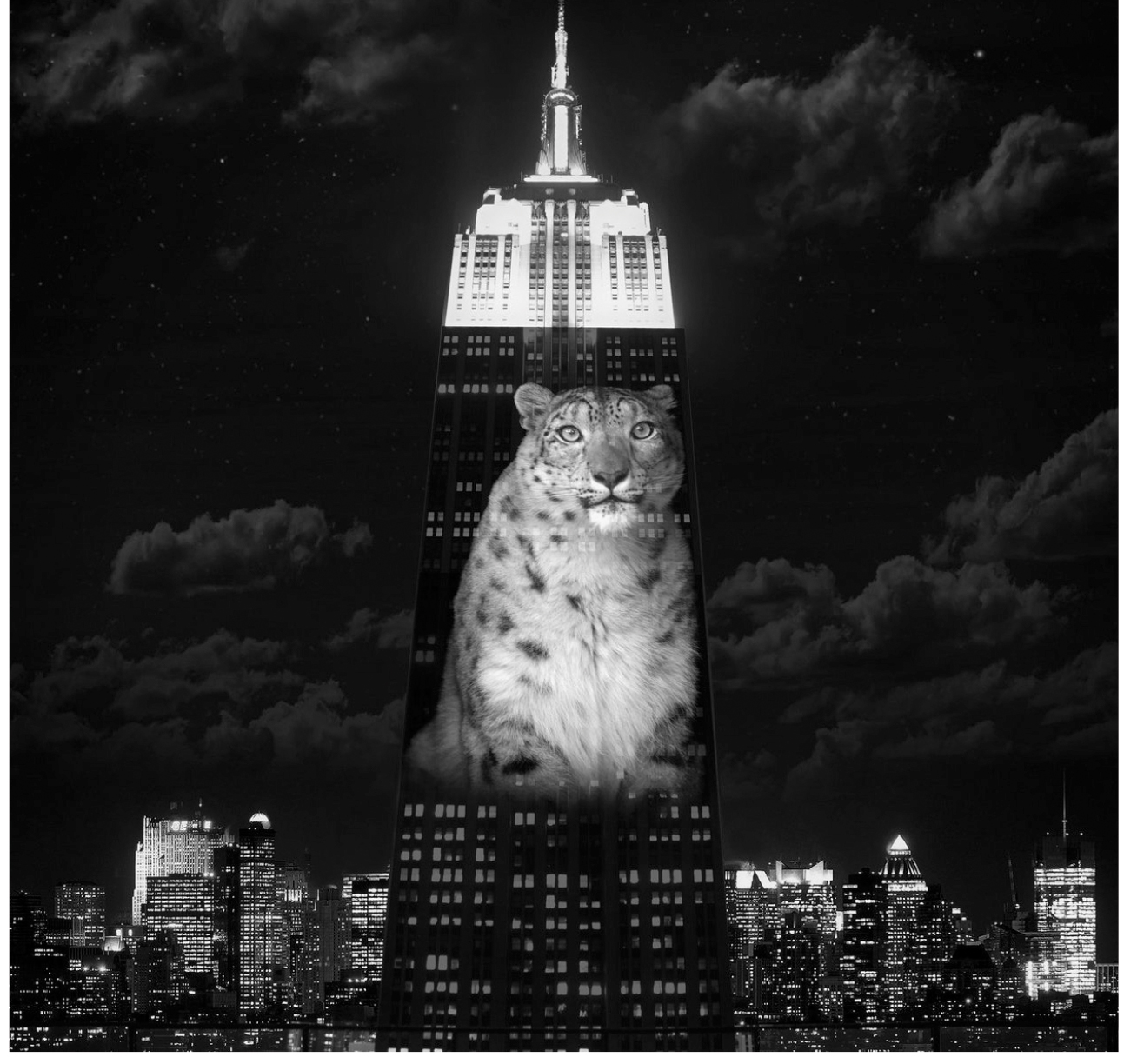

Fifty stories high,

a colossal white leopard in the wintry city

is the upper half of the Empire State Building,

thanks to twenty thousand lumen projectors,

not just a trick, but a cunning cat

with other endangered species.

I hear its cry above the city traffic.

Let the leopard take over Manhattan, meowing,

growling with hunger louder than a fire truck.

I bring rats and gallons of milk,

as I will every day, hoping it will stay.

Sometimes it holds me by the back of my neck,

carries me wherever it wants to go.

I call it Poetry. I call it my pussy cat,

my kitten I’ve been sleeping with all my life.

My big cat reads, respects the stone lions

in front of the 42nd Street Library.

In the main reading room it works, studies

which monuments the cats of Rome,

Paris, and Jerusalem make home—

the periphrastic reasons, causes, why.

Poetry slouches its way up Broadway

north toward the Himalayas.

It takes me through avalanche and blizzards,

the sunlight and lanterns

of the Analects, Gita, Koran, Bible.

We roll together, I discover its privates.

The gigantic cat has got me by the throat,

holds me down by a paw in the snow.

I never thought I would go like this.

I always felt death was supernatural. If I can,

I told Zhu Ming, my Christian-Buddhist cousin,

I’ll come back as a butterfly in winter

so she’ll know it’s me.

It was a shock for me to realize

I have not seen the Atlantic Ocean

for two years, not seen the truth she represents,

the beautiful and terrible world,

not embraced her or been embraced,

tasted and smelled her, knocked off my feet,

not heard her many languages.

I address her only with baby talk,

her face more familiar than any face I know,

the face of every woman I’ve ever known,

the most protective and life-threatening.

When I saw her every morning first thing,

there was always a kiss,

the stroking of my face and body going one way

then the slap on the way back.

I’ve thought I’d be buried under a loved red oak

on a day like this in August

when trees are happy and beautiful as a tree can be

except perhaps some in snow,

but now I prefer you throw me overboard

into the city of God. The Atlantic nods and smiles.

She’s heard so much of my nonsense through the years,

seems to remember everything I ever said or wrote.

The tide comes in. She forgets everything I ever said or wrote.

The faces on the city streets and seabirds

all look very familiar to me.

They’ve got my number.

Numerology is familiar to me as chocolate.

Because nine means life in Hebrew,

I eat nine chocolates a day

from a box, its lid a painting of crawling Aristotle,

Phyllis riding his back.

Ocean around me horizon to horizon,

I’m heading east, bound for Dublin, Plymouth,

Barcelona, Venice, and Pireaus—

I’ve been known to trust only the stars

and my own hopeless intuition,

not instruments, even in a storm.

Always lost, I’m free, self-reliant.

The first sight of land, I think is Ireland, is Norway

—Ibsen today, not Yeats or Joyce.

Soon, using charts, I’m off to China

(after all, the Chinese invented the compass).

Finally, my body tossed overboard

into the city of the disGodded,

far from any country of prayer,

with nine chocolates in my pocket,

with the ashes of my dogs at my feet—

not Nicky, what’s left of her

still under the Japanese maple.

The Atlantic nods and smiles.

Now it is easier to write than to read.

When I was a child, before I knew the word for love

or snowstorm, before I remember a tree,

I saw a pigeon in a blizzard, knocking

against the kitchen window, trying to get in.

My first clear memory of terror,

I kept secret, my intimations

I kept secret.

This winter I hung a gray and white stuffed

felt seagull from the ring of my window shade,

a reminder of good times by the sea,

Chekhov and impossible love.

It pleases me the gull

sometimes lifts a wing in the drafty room.

Once when looking at the gull I saw

through the window a living seagull glide

toward me then disappear—what a rush of life!

I remember its here-ness, while in the room

the senseless symbol, little more than a bedroom slipper

dangled on a string.

My childhood hangs like a gull

in the distant sky,

behind loneliness,

it watches some dark thing below.

I saw before an approaching storm

the seagull stays off the ocean.

On a trawler off Montauk

I am heading home full throttle,

cleaning my catch of striped bass,

seagulls dive, fighting, desperate for the guts—

their faces inches away from mine,

every face different, a sight I never saw before.

For a few seconds, I am part of the flock—

my soul rises out of me,

struggles, surrounded by their cries.

I drift, glide off like my childhood

into the gunmetal sky.