Cassio awoke with a jolt. He’d been dreaming of spiders lowering toward him, crawling slowly across his lips.

The circular light above him was so powerful it hurt his eyes. He squeezed them shut; when he tried to move his hand he realized that he was wired up. Now Piera’s head eclipsed the lamp, and she smiled at him through the exorbitant light. She showed him the stinger in her hands: a syringe half-full of precious cargo. Cassio shuddered in light terror, realized he’d done so when Piera laughed and caressed his head.

“We can abort the mission whenever we want—don’t forget that.”

Cassio shook his head and relaxed there on the bed, remembering their conversation.

So it could be said that this machine is the place where computer viruses and biological viruses live together in the same medium—the same ecosystem.

It’s still dark outside, but they have to get out of the subterranean lab before their colleagues start coming in, can’t let themselves be found anywhere near it. Cassio suggests going to get breakfast somewhere with a view of Nahuel Huapi. Pleased with himself, with the strength of his convictions, he helps her put on her coat.

They walk along the big avenue beside the lake, past the cathedral designed by Bustillo in the 1940s, its immense vitreaux bearing images of natives assassinating clerics. To one side is a disco called Cerebro, blue and neon fuchsia. To the other, the silent mountains navigate the lunar stillness.

Up the street comes a group of adolescents still drunk from the night before—they can barely walk. Cassio watches Piera out of the corner of his eye.

“Have you been to Chile?” he asks.

“When I was a girl. Valparaiso. I don’t remember it at all.”

“Puerto Montt isn’t far from here.”

“I know, but I didn’t go. I’d love to, though.”

“It’s right on the other side of these mountains.”

“Yeah . . .”

“You really should go. They have this bivalve food festival.”

“Do they?”

Piera looks at him, suddenly alert.

“Marine fauna is amazing,” he says.

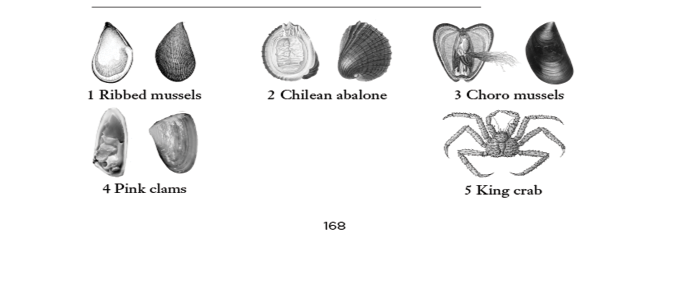

“Ribbed mussels1 are good,” she concedes.

Cassio stares at her intensely.

“And Chilean abalone,”2 he says.

“And choro mussels,”3 she answers immediately.

No one is going to beat her at Chilean mollusks.

“Pink clams,”4 he says.

“King crab.”5

“Mayonnaise.”

“Not actually a seafood.”

“But an essential element in the Chiloé Island diet.”

They walk on silently. Swirls of incandescent beams advance above them like heavenly armies, wreathing the earth’s southernmost atmosphere in pinkish tones that scatter as the light grows.

Beneath the surgical lamp, Cassio smiled. He opened his eyes, let the light burn his pupils a bit. Piera leaned in close, her lips parted. She was focused on expelling the air from the syringe, and it seemed to Cassio that her lips were even redder now, she was more Snow White, more Monica Lewinsky than ever, and yet completely herself. He was on the verge of leaving his anthropoidal specificity behind, melding himself astrally with the interior of the machine, and he tried to think of something to say, knowing that nothing but her voice would stay with him as he descended beyond the shoreline where his fellow humans grazed. A chill ran through his tennis-shoed feet. Had the fever started already? It wasn’t supposed to begin for a few minutes more.

“I just have to get used to feeling feverish, right?”

She leaned over him and put a finger across his lips, opened her eyes wide and stared straight into his. Her lips at his ear:

“I haven’t given you the shot yet.”

A moment later a beam of light shot through his chest. Cassio exhaled; the drug made its way toward his extremities and began to do its work. He babbled for a time, then fell into a deep sleep.

The previous week had been grueling. They’d only finished preparing the virus in Balseiro’s DNA sequencer a few hours ago. This was Piera’s first experiment involving a computer virus, and Cassio’s first with a biological one; for the first time, in addition to being the demiurge, he would be the vector of contagion. As he lost consciousness, Piera listed these landmark achievements to herself—she would have to find some canned juice to celebrate. It occurred to her that they were now junkies addicted to a drug they’d only just invented. Not bad, not bad at all.

Cassio was still asleep; part of his face looked like it was immersed in a pond, with fluid circles moving about beneath his eyelids. The needle had done its work, sent the drug navigating silently through his waterways. For a few seconds he’d felt the skin of his face changing color: the veinlets shimmered yellow, then green around his red nostrils. It couldn’t be seen, was only a sensation. Now he snorted, took a deep breath. His face gleamed as if in the light of a faint green halo.

He looked like a gigantic child there in the bed—or, better, like the carapace of a child enclosing an attractive man. Piera thought about smelling him while he slept, and the thought itself impressed her as the sort of thing that others would respect. She told herself that the impulse itself couldn’t be helped given how nervous she was about the experiment—but she didn’t want to unleash processes that she might not be able to control. It seemed ironic that her Victorian instincts would lead her to contemplate these details of fleshy desire right after she’d shot a virus into Cassio’s veins. The monitors showed that his condition was stable. And he was cute like this, asleep—he looked like he could be trusted.