Dawn had scarcely broken when Pompey, clad in glittering silver armor and flanked by his eighteen-year-old brother and by Varro, led a little party of clerks and scribes into the marketplace of Auximum. There he planted his father’s standard in the middle of its open space and waited with ill—concealed impatience until his secretariat had assembled itself behind a series of trestle tables, sheets of paper at the ready, reed pens sharpened, cakes of ink dissolved in heavy stone wells.

By the time all this was done, the crowd had gathered so thickly that it spilled out of the square into the streets and lanes converging upon it. Light and lithe, Pompey leaped onto a makeshift podium beneath Pompey Strabo’s woodpecker standard.

“Well, it’s come!” he shouted. “Lucius Cornelius Sulla has landed in Brundisium to claim what is rightfully his—an uninterrupted imperium, a triumph, the privilege of depositing his laurels at the feet of Jupiter Optimus Maximus inside the Capitol of Rome! At just about this time last year, the other Lucius Cornelius—he cognominated Cinna—was not far away from here trying to enlist my father’s veterans in his cause. He did not succeed. Instead, he died. Today you see me. And today I see many of my father’s veterans standing before me. I am my father’s heir! His men are my men. His past is my future. I am going to Brundisium to fight for Sulla, for he is in the right of it. How many of you will come with me?’’

Short and simple, thought Varro, lost in admiration. Maybe the young man was correct about vaulting into the consul’s curule chair on his spear rather than on a wave of words. Certainly no face he could discern in that crowd seemed to find Pompey’s speech lacking. No sooner had he finished than the women began to drift away clucking about the imminent absence of husbands and sons, some wringing their hands at the thought, some already engrossed in the practicalities of filling kit bags with spare tunics and socks, some looking studiously at the ground to hide sly smiles. Pushing excited children out of the way with mock slaps and kicks, the men shoved forward to cluster about those trestle tables. Within moments, Pompey’s clerks were scribbling strenuously.

From a nice vantage spot high on the steps of Auximum’s old temple of Picus, Varro sat and watched the activity. Had they ever volunteered so lightheartedly for cross-eyed Pompey Strabo’s campaigns? he wondered. Probably not. That one had been the lord, a hard man but a fine commander; they would have served him with goodwill but sober faces. For the son, it was clearly different. I am looking at a phenomenon, Varro thought. The Myrmidons could not have gone more happily to fight for Achilles, nor the Macedonians for Alexander the Great. They love him! He’s their darling, their mascot, their child as much as their father.

A vast bulk deposited itself on the step next to him, and Varro turned his head to see a red face topped by red hair; a pair of intelligent blue eyes were busy assessing him, the only stranger present.

“And who might you be?” asked the ruddy giant.

“My name is Marcus Terentius Varro, and I’m a Sabine.”

“Like us, eh? Well, a long time ago, at any rate.” A horny paw waved in the direction of Pompey. “Look at him, will you? Oh, we’ve been waiting for this day, Marcus Terentius Varro the Sabine! Be he not the Goddess’s honeypot?”

Varro smiled. “I’m not sure I’d choose that way of putting it, but I do see what you mean.”

“Ah! You’re not only a gentleman with three names, you’re a learned gentleman! A friend of his, might you be?”

“I might be.”

“And what might you do for a crust, eh?”

“In Rome, I’m a senator. But in Reate, I breed mares.”

“What, not mules?”

“It’s better to breed the mares than their mule offspring. I have a little bit of the rosea rura, and a few stud donkeys too.’’

“How old might you be?’’

“Thirty-two,” said Varro, enjoying himself immensely.

But suddenly the questions ceased; Varro’s interlocutor disposed himself more comfortably by resting one elbow on the step above him and stretching out a Herculean pair of legs to cross his ankles. Fascinated, the diminutive Varro eyed grubby toes almost as large as his own fingers.

“And what might your name be?” he asked, falling into the local vernacular quite naturally.

“Quintus Scaptius.”

“Might you have enlisted?”

“All Hannibal’s elephants couldn’t stop me!”

“Might you be a veteran?”

“Joined his daddy’s army when I was seventeen. That was eight years ago, but I’ve already served in twelve campaigns, so I don’t have to join up anymore unless I might want to,” said Quintus Scaptius.

“But you did want to.”

“Hannibal’s elephants, Marcus Terentius, Hannibal’s elephants!”

“Might you be of centurion rank?’’

“I might be for this campaign.”

While they talked, Varro and Scaptius kept their eyes on Pompey, who stood just in front of the middle table joyfully hailing this man or that among the throng.

“He says he’ll march before this moon has run her course,” Varro observed, “but I fail to see how. I admit none of these men here today will need much if any training, but where’s he going to get enough arms and armor? Or pack animals? Or wagons and oxen? Or food? And what will he do for money to keep his great enterprise going?’’

Scaptius grunted, apparently an indication of amusement. “He does not need to worry about any of that! His daddy gave each of us our arms and armor at the start of the war against the Italians; then after his daddy died, the boy told us to hang on to them. We each got a mule, and the centurions got the carts and oxen. So we’d be ready against the day. You’ll never catch the Pompeii napping! There’s wheat enough in our granaries and lots of other food in our storehouses. Our women and children won’t go hungry because we’re eating well on campaign.”

“And what about money?” asked Varro gently.

“Money?” Scaptius dismissed this necessity with a sniff of contempt. “We served his daddy without seeing much of it, and that’s the truth. Wasn’t any to be had in those days. When he’s got it, he’ll give it to us. When he hasn’t got it, we’ll do without. He’s a good master.”

“So I see.”

Lapsing into silence, Varro studied Pompey with fresh interest. Everyone told tales about the legendary independence of Pompey Strabo during the Italian War: how he had kept his legions together long after he was ordered to disband them, and how he had directly altered the course of events in Rome because he had not disbanded them. No massive wage bills had ever turned up on the Treasury’s books when Cinna had them audited after the death of Gaius Marius; now Varro knew why. Pompey Strabo hadn’t bothered to pay his troops. Why should he, when he virtually owned them?

At this moment Pompey left his post to stroll across to Picus’s temple steps.

“I’m off to find a campsite,” he said to Varro, then gave the Hercules sitting next to Varro a huge grin. “Got in early, I see, Scaptius.”

Scaptius lumbered to his feet. “Yes, Magnus. I’d best be getting home to dig out my gear, eh?”

So everyone called him Magnus! Varro too rose. “I’ll ride with you, Magnus.”

The crowd was dwindling, and women were beginning to come back into the marketplace; a few merchants, hitherto thwarted, were busy putting up their booths, slaves rushing to stock them. Loads of dirty washing were dropped on the paving around the big fountain in front of the local shrine to the Lares, and one or two girls hitched up their skirts to climb into the shallow water. How typical this town is, thought Varro, walking a little behind Pompey: sunshine and dust, a few good shady trees, the purr of insects, a sense of timeless purpose, wrinkled winter apples, busy folk who all know far too much about each other. There are no secrets here in Auximum!

“These men are a fierce lot,” he said to Pompey as they left the marketplace to find their horses.

“They’re Sabines, Varro, just like you,” said Pompey, “even if they did come east of the Apennines centuries ago.”

“Not quite like me!” Varro allowed himself to be tossed into the saddle by one of Pompey’s grooms. “I may be a Sabine, but I’m not by nature or training a soldier.”

“You did your stint in the Italian War, surely.”

“Yes, of course. And served in my ten campaigns. How quickly they mounted up during that conflagration! But I haven’t thought of a sword or a suit of chain mail since it ended.’’

Pompey laughed. “You sound like my friend Cicero.”

“Marcus Tullius Cicero? The legal prodigy?”

“That’s him, yes. Hated war. Didn’t have the stomach for it, which my father didn’t understand. But he was a good fellow all the same, liked to do what I didn’t like to do. So between us we kept my father mighty pleased without telling him too much.” Pompey sighed. “After Asculum Picentum fell he insisted on going off to serve under Sulla in Campania. I missed him!”

*

In two market intervals of eight days each Pompey had his three legions of veteran volunteers camped inside well-fortified ramparts some five miles from Auximum on the banks of a tributary of the Aesis River. His sanitary dispositions within his camp were faultless, and care of them rigidly policed. Pompey Strabo had been a more typical product of his rural origins, had known only one way to deal with wells, cesspits, latrines, rubbish disposal, drainage: when the stink became unbearable, move on. Which was why he had died of fever outside Rome’s Colline Gate, and why the people of the Quirinal and Viminal, their springs polluted from his wastes, had done such insult to his body.

Growing ever more fascinated, Varro watched the evolution of his young friend’s army, and marveled at the absolute genius Pompey showed for organization, logistics. No detail, regardless how minute, was overlooked; yet at the same time the enormous undertakings were executed with the speed only superb efficiency permitted. I have been absorbed into the very small private circle of a true phenomenon, he thought: he will change the way our world is, he will change the way we see our world. There is not one single iota of fear in him, nor one hairline crack in his self-confidence.

However, Varro reminded himself, others too have shaped equally well before the turmoil begins. What will he be like when he has his enterprise running, when opposition crowds him round, when he faces—no, not Carbo or Sertorius—when he faces Sulla? That will be the real test! Same side or not, the relationship between the old bull and the young bull will decide the young bull’s future. Will he bend? Can he bend? Oh, what does the future hold for someone so young, so sure of himself? Is there any force or man in the world capable of breaking him?

Definitely Pompey did not think there was. Though he was not mystical, he had created a spiritual environment for himself that fitted certain instincts he cherished about his nature. For instance, there were qualities he knew he owned rather than possessed—invincibility, invulnerability, inviolability—for since they were outside him as much as inside, ownership seemed more correct than possession. It was just as if, while some godly ichor coursed through him, some godly miasma wrapped him round as well. Almost from infancy he had lived within the most colossal daydreams; in his mind he had generated ten thousand battles, ridden in the antique victor’s chariot of a hundred triumphs, stood time and time again like Jupiter come to earth while Rome bowed down to worship him, the greatest man who had ever lived.

Where Pompey the dreamer differed from all others of that sort was in the quality of his contact with reality—he saw the actual world with hard and sharp acuity, never missed possibility or probability, fastened his mind leechlike upon facts the size of mountains, facts as diminutive as one drop of clearest water. Thus the colossal daydreams were a mental anvil upon which he hammered out the shape of the real days, tempered and annealed them into the exact framework of his actual life.

So he got his men into their centuries, their cohorts, their legions; he drilled them and inspected their accoutrements; he culled the too elderly from his pack animals and sounded blows on the axles of his wagons, rocked them, had them driven fast through the rough ford below his camp. Everything would be perfect because nothing could be allowed to happen that would show him up as less than perfect himself.

*

Twelve days after Pompey had begun to assemble his troops, word came from Brundisium. Sulla was marching up the Via Appia amid scenes of hysterical welcome in every hamlet, village, town, city. But before Sulla left, the messenger told Pompey, he had called his army together and asked it to swear an oath of personal allegiance to him. If those in Rome had ever doubted Sulla’s determination to extricate himself from any threat of future prosecutions for high treason, the fact that his army swore to uphold him—even against the government of Rome—told all men that war was now inevitable.

And then, Pompey’s messenger had gone on to say, Sulla’s soldiers had come to him and offered him all their money so that he could pay for every grain of wheat and leaf of vegetable and seed of fruit as he moved through the heartland of Calabria and Apulia; they would have no dark looks to spoil their general’s luck, they would have no trampled fields, dead shepherds, violated women, starving children. All would be as Sulla wanted it; he could pay them back later, when he was master of the whole of Italy as well as Rome.

The news that the southern parts of the peninsula were very glad to welcome Sulla did not quite please Pompey, who had hoped that by the time he reached Sulla with his three legions of hardened veterans, Sulla would be in sufficient trouble to need him. However, that was clearly not to be; Pompey shrugged and adapted his plans to the situation as it had been reported to him.

“We’ll march down our coast to Buca, then head inland for Beneventum,” he said to his three chief centurions, who were commanding his three legions. By rights these jobs should have gone to high—born military tribunes, whom he could have found had he tried. But high—born military tribunes would have questioned Pompey’s right to general his army, so Pompey had preferred to choose his subordinates from among his own people, much though certain high—born Romans might have deplored it had they known.

“When do we move?” asked Varro, since no one else would.

“Eight days before the end of April,” said Pompey.

*

Then Carbo entered the scene, and Pompey had to change his plans yet again.

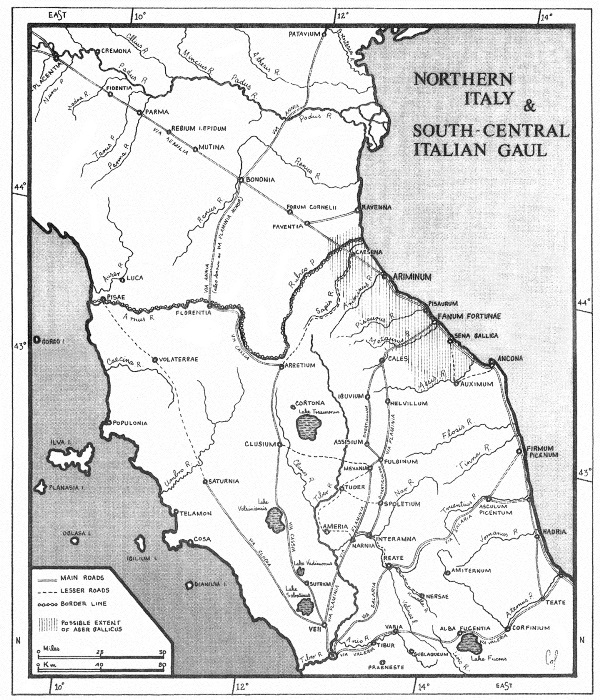

From the western Alps the straight line of the Via Aemilia bisected Italian Gaul all the way to the Adriatic Sea at Ariminum; from Ariminum another excellent road skirted the coast to Fanum Fortunae, where began the Via Flaminia to Rome. This gave Ariminum a strategic importance only equaled by Arretium, which dominated access to Rome west of the Apennines.

It was therefore logical that Gnaeus Papirius Carbo—twice consul of Rome and now governor of Italian Gaul—should put himself, his eight legions and his cavalry into camp on the fringes of Ariminum. From this base he could move in three directions: along the Via Aemilia through Italian Gaul toward the western Alps; along the Adriatic coast in the direction of Brundisium; and along the Via Flaminia to Rome.

For eighteen months he had known Sulla would come, and that of course would be Brundisium. But too many men still lingered in Rome who might when the time came side with Sulla, though they declared themselves completely neutral; they were all men with the political clout to overthrow the present government, which made Rome a necessary target. And Carbo also knew that Metellus Pius the Piglet had gone to earth in Liguria, bordering the western Alps of Italian Gaul; with Metellus Pius were two good legions he had taken with him out of Africa Province after Carbo’s adherents had ejected him from Africa. The moment the Piglet heard that Sulla had landed, Carbo was certain he would march to join Sulla, and that made Italian Gaul vulnerable too.

Of course there were the sixteen legions sitting in Campania, and these were much closer to Brundisium than Carbo in Ariminum; but how reliable were the consuls of this year, Norbanus and Scipio Asiagenus? Carbo couldn’t be sure, with his own iron will removed from Rome herself. At the end of last year he had been convinced of two things: that Sulla would come in the spring, and that Rome would be more inclined to oppose Sulla if Carbo himself were absent from Rome. So he had ensured the election of two staunch followers in Norbanus and Scipio Asiagenus and then given himself the governorship of Italian Gaul in order to keep an eye on things and be in a position to act the moment it became necessary. His choice of consuls had been—in theory anyway—good, for neither Norbanus nor Scipio Asiagenus could hope for mercy from Sulla. Norbanus was a client of Gaius Marius’s, and Scipio Asiagenus had disguised himself as a slave to escape from Aesernia during the Italian War, an action which had disgusted Sulla. Yet were they strong enough? Would they use their sixteen legions like born generals, or would they miss their chances? Carbo just didn’t know.

On one thing he had not counted. That Pompey Strabo’s heir, mere boy that he was, would have the audacity to raise three full legions of his father’s veterans and march them to join Sulla! Not that Carbo took the young man seriously. It was those three legions of veterans that worried Carbo. Once they reached Sulla, Sulla would use them brilliantly.

It was Carbo’s quaestor, the excellent Gaius Verres, who had brought the news to Carbo of Pompey’s projected expedition.

“The boy will have to be stopped before he can start,” said Carbo, frowning. “Oh, what a nuisance! I’ll just have to hope that Metellus Pius doesn’t move out of Liguria while I’m dealing with young Pompeius, and that the consuls can cope with Sulla.”

“It won’t take long to deal with young Pompeius,” said Gaius Verres, tone confident.

“I agree, but that doesn’t make him less of a nuisance,” said Carbo. “Send my legates to me now, would you?”

Carbo’s legates proved difficult to locate; Verres chased from one part of the gigantic camp to another for a length of time he knew would not please Carbo. Many things occupied his mind while he searched, none of them related to the activities of Pompey Strabo’s heir, young Pompeius. No, what preyed upon the mind of Gaius Verres was Sulla. Though he had never met Sulla (there was no reason why he ought, since his father was a humble backbencher senator, and his own service during the Italian War had been with Gaius Marius and then Cinna), he remembered the look of Sulla as he had walked in the procession going to his inauguration as consul, and had been profoundly impressed. As he was not martial by nature, it had never occurred to Verres to join Sulla’s expedition to the east, nor had he found the Rome of Cinna and Carbo an unendurable place. Verres liked to be where the money was, for he had expensive tastes in art and very high ambitions. Yet now, as he chased Carbo’s senior legates, he was beginning to wonder if it might not be time to change sides.

Strictly speaking, Gaius Verres was proquaestor rather than quaestor; his official stint as quaestor had ended with the old year. That he was still in the job was due to Carbo, whose personal appointee he had been, and who declared himself so well satisfied that he wanted Verres with him when he went to govern Italian Gaul. And as the quaestor’s function was to handle his superior’s money and accounts, Gaius Verres had applied to the Treasury and received on Carbo’s behalf the sum of 2,235,417 sesterces; this stipend, totted up with due attention to every last sestertius (witness those 417 of them!), was intended to cover Carbo’s expenses—to pay his legions, victual his legions, assure a proper life—style for himself, his legates, his servants and his quaestor, and defray the cost of a thousand and one minor items not able to be classified under any of the above.

Though April was not yet done, something over a million and a half sesterces had already been swallowed up, which meant that Carbo would have to ask the Treasury for more before too long. His legates lived extremely well, and Carbo himself had long grown used to having Rome’s public resources at his fingertips. Not to mention Gaius Verres; he too had stickied his hands in a pot of honey before dipping them deeply into the moneybags. Until now he had kept his peculations unobtrusive, but, he decided with fresh insight into his present position, there was no point in being subtle any longer! As soon as Carbo’s back was turned to deal with Pompey’s three legions, Gaius Verres would be gone. Time to change sides.

And so indeed Gaius Verres went. Carbo took four of his legions—but no cavalry—the following dawn to deal with Pompey Strabo’s heir, and the sun was not very high when Gaius Verres too departed. He was quite alone save for his own servants, and he did not follow Carbo south; he went to Ariminum, where Carbo’s funds lay in the vaults of a local banker. Only two persons had the authority to withdraw it: the governor, Carbo, and his quaestor, Verres. Having hired twelve mules, Verres removed a total of forty-eight half—talent leather bags of Carbo’s money from the banker’s custody, and loaded them upon his mules. He did not even have to offer an excuse; word of Sulla’s landing had already flown around Ariminum faster than a summer storm, and the banker knew Carbo was on the march with half his infantry.

Long before noon, Gaius Verres had escaped the neighborhood with six hundred thousand sesterces of Carbo’s official allowance, bound via the back roads first for his own estates in the upper Tiber valley, and then—the lighter of twenty-four talents of silver coins—for wherever he might find Sulla.

Oblivious to the fact that his quaestor had decamped, Carbo himself went down the Adriatic coast toward Pompey’s position near the Aesis. His mood was so sanguine that he did not move with speed, nor did he take special precautions to conceal his advent. This was going to be a good exercise for his largely unblooded troops, nothing more. No matter how formidable three legions of Pompey Strabo’s veterans might sound, Carbo was quite experienced enough to understand that no army can do better than its general permits it to. Their general was a kid! To deal with them would therefore be child’s play.

*

When word of Carbo’s approach was brought to him, Pompey whooped with joy and assembled his soldiers at once.

“We don’t even have to move from our own lands to fight our first battle!” he shouted to them. “Carbo himself is coming down from Ariminum to deal with us, and he’s already lost the fight! Why? Because he knows I’m in command! You, he respects. Me, he doesn’t. You’d think he’d realize The Butcher’s son would know how to chop up bones and slice meat, but Carbo is a fool! He thinks The Butcher’s son is too pretty and precious to bloody his hands at his father’s trade! Well, he’s wrong! You know that, and I know that. So let’s teach it to Carbo!”

Teach it to Carbo they did. His four legions came down to the Aesis in a fashion orderly enough, and waited in disciplined ranks for the scouts to test the river crossing, swollen from the spring thaw in the Apennines. Not far beyond the ford, Carbo knew Pompey still lay in his camp, but such was his contempt that it never occurred to him Pompey might be in his own vicinity.

Having split his forces and sent half across the Aesis well before Carbo arrived, Pompey fell on Carbo at the moment when two of his legions had made the crossing, and two were about to do so. Both jaws of his pincer attacked simultaneously from out of some trees on either bank, and carried all before them. They fought to prove a point—that The Butcher’s son knew his trade even better than his father had. Doomed by his role as the general to remain on the south bank of the river, Pompey couldn’t do what he most yearned to do—go after Carbo in person. Generals, his father had told him many times, must never put the base camp out of reach in case the battle didn’t develop as planned and a swift retreat became necessary. So Pompey had to watch Carbo and his legate Lucius Quinctius rally the two legions left on their bank of the Aesis, and flee back toward Ariminum. Of those on Pompey’s bank, none survived. The Butcher’s son did indeed know the family trade, and crowed jubilantly.

Now it was time to march for Sulla!

*

Two days later, riding a big white horse which he said was the Pompeius family’s Public Horse—so called because the State provided it—Pompey led his three legions into lands fiercely anti—Rome a few short years earlier. Picentines of the south, Vestini, Marrucini, Frentani, all peoples who had struggled to free the Italian Allied states from their long subjection to Rome. That they had lost was largely due to the man Pompey marched to join—Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Yet no one tried to impede the army’s progress, and some in fact came asking to enlist. Word of his defeat of Carbo had outstripped Pompey, and they were martial peoples. If the fight for Italia was lost, there were other causes; the general feeling seemed to be that it was better to side with Sulla than with Carbo.

Everyone’s spirits were high as the little army left the coast at Buca and headed on a fairly good road for Larinum in central Apulia. Two eight—day market intervals had gone by when Pompey’s eighteen thousand veteran soldiers reached it, a thriving small city in the midst of rich agricultural and pastoral country; no one of importance in Larinum was missing from the delegation which welcomed Pompey—and sped him onward with subtle pressure.

His next battle lay not three miles beyond the town. Carbo had wasted no time in sending a warning to Rome about The Butcher’s son and his three legions of veterans, and Rome had wasted no time in seeking to prevent amalgamation between Pompey and Sulla. Two of the Campanian legions under the command of Gaius Albius Carrinas were dispatched to block Pompey’s progress, and encountered Pompey while both sides were on the march. The engagement was sharp, vicious, and quite decisive; Carrinas stayed only long enough to see that he stood no chance to win, then beat a hasty retreat with his men reasonably intact—and greater respect for The Butcher’s son.

By this time Pompey’s soldiers were so settled and secure that the miles swung by under their hobnailed, thick—soled caligae as if no effort was involved; they had passed into their third hundred of these miles with no more than a mouthful or two of sour weak wine to mark the event. Saepinum was reached, a smaller place than Larinum, and Pompey had news that Sulla was now not far away, camped outside Beneventum on the Via Appia.

But first another battle had to be fought. Lucius Junius Brutus Damasippus, brother of Pompey Strabo’s old friend and senior legate, tried to ambush the son in a small section of rugged country between Saepinum and Sirpium. Pompey’s overweening confidence in his ability seemed not to be misplaced; his scouts discovered where Brutus Damasippus and his two legions were concealed, and it was Pompey who fell upon Brutus Damasippus without warning. Several hundred of Brutus Damasippus’s men died before he managed to extricate himself from a difficult position, and fled in the direction of Bovianum.

After none of his three battles had Pompey attempted to pursue his foes, but not for the reasons men like Varro and the three primus pilus centurions assumed; the facts that he didn’t know the lay of the land, nor could be sure that these were not diversions aimed at luring him into the arms of a far bigger force, did not so much as intrude into Pompey’s thoughts. For Pompey’s mind was obsessed to the exclusion of all else with the coming meeting between himself and Lucius Cornelius Sulla.

Visions of it unrolled before his sightless dreaming eyes like a moving pageant—two godlike men with hair of flame and faces both strong and beautiful uncoiled from their saddles with the grace and power of giant cats and walked with measured stately steps toward each other down the middle of an empty road, its sides thronged with every traveler and every last inhabitant of the countryside, an army behind each of these magnificent men, and every pair of eyes riveted upon them. Zeus striding to meet Jupiter. Ares striding to meet Mars. Hercules striding to meet Milo. Achilles striding to meet Hector. Yes, it would be hymned down the ages so loudly that it would put Aeneas and Turnus to shame! The first encounter between the two colossi of this world, the two suns in its sky—and while the setting sun was still hot and still strong, its course was nearing an end. Ah! But the rising sun! Hot and strong already, yet with all the soaring vault before it in which to grow ever hotter, ever stronger. Thought Pompey exultantly, Sulla’s sun is westering! Whereas mine is barely above the eastern horizon.

*

He sent Varro ahead to present his compliments to Sulla and to give Sulla an account of his progress from Auximum, the tally of those he had killed, the names of the generals he had defeated. And to ask that Sulla himself venture down the road to meet him so that everyone could witness his coming in peace to offer himself and his troops to the greatest man of this age. He didn’t ask Varro to add, “or of any other age” – that he was not prepared to admit, even in a flowery greeting.

Every detail of this meeting had been fantasized a thousand times, even down to what Pompey felt he ought to wear. In the first few hundred passes he had seen himself clad from head to foot in gold plate; then doubt began to gnaw, and he decided golden armor was too ostentatious, might be labeled crass. So for the next few hundred passes he saw himself clad in a plain white toga, shorn of all military connotations and with the narrow purple stripe of the knight slicing down the right shoulder of his tunic; then doubt gnawed again, and he worried that the white toga would merge into the white horse to produce an amorphous blob. The final few hundred passes saw him in the silver armor his father had presented to him after the siege of Asculum Picentum had concluded; doubt did not gnaw at all, so he liked that image of self best.

Yet when his groom assisted him into the saddle of his big white Public Horse, Gnaeus Pompeius (Magnus) was wearing the very plainest of steel cuirasses, the leather straps of his kilt were unadorned by bosses or fringes, and the helmet on his head was standard issue to the ranks. It was his horse he bedizened, for he was a knight of the eighteen original centuries of the First Class, and his family had held the Public Horse for generations. So the horse wore every conceivable knightly trapping of silver buttons and medallions, silver—encrusted scarlet leather harness, an embroidered blanket beneath a wrought and ornamented saddle, a clinking medley of silver pendants. He looked, Pompey congratulated himself as he set off down the middle of the empty road with his army in rank and file behind him, like a genuine no-nonsense soldier—a workman, a professional. Let the horse proclaim his glory!

Beneventum lay on the far side of the Calor River, where the Via Appia made junction with the Via Minucia from coastal Apulia and Calabria. The sun was directly overhead when Pompey and his legions came over the brow of a slight hill and looked down to the Calor crossing. And there on this side of it, waiting in the middle of the road upon an unutterably weary mule, was Lucius Cornelius Sulla. Attended only by Varro. The local populace!—where were they? Where were Sulla’s legates, his troops? Where the travelers?

Some instinct made Pompey turn his head and bark to the standard—bearer of his leading legion that the soldiers would halt, remain where they were. Then, hideously alone, he rode down the slope toward Sulla, his face set into a mask so solid he felt as if he had dipped it in plaster. When he came within a hundred paces of the mule, Sulla more or less fell off it, though he kept his feet because he threw one arm around the mule’s neck and fastened his other hand upon the mule’s long bedraggled ear. Righting himself, he began to walk down the middle of the empty road, his gait as wide—based as any sailor’s.

Down from his clinking Public Horse leaped Pompey, not sure if his legs would hold him; but they did. Let one of us at least do this properly, he thought, and strode out.

Even at a distance he had realized that this Sulla bore absolutely no resemblance to the Sulla he remembered, but as he drew ever closer, Pompey began to discern the ravages of time and awful malaise. Not with sympathy or pity, but with stupefied horror, a physical reaction so profound that for a moment he thought he would vomit.

For one thing, Sulla was drunk. That, Pompey might have been able to forgive, had this Sulla been the Sulla he remembered on the day of his inauguration as consul. But of that beautiful and fascinating man nothing was left, not even the dignity of a thatch of greyed or whitened hair. This Sulla wore a wig to cover his hairless skull, a hideous ginger—red affair of tight little curls below which two straight silver tongues of his own hair grew in front of his ears. His teeth were gone, and their going had lengthened his dented chin, made the mouth into a puckered gash below that unmistakable nose with the slight crease in its tip. The skin of his face looked as if it had been partially flayed, most of it a raw and bloody crimson, some few places still showing their original whiteness. And though he was thin to the point of scrawniness, at some time in the not too distant past he must have grown enormously fat, for the flesh of his face had fallen into crevices, and vast hollow wattles transformed his neck into a vulturine travesty.

Oh, how can I shine against the backdrop of this mangled piece of human wreckage? wailed Pompey to himself, battling to stem the scorching tears of disappointment.

They were almost upon each other. Pompey stretched out his right hand, fingers spread, palm vertical.

“Imperator!” he cried.

Sulla giggled, made a huge effort, stretched out his own hand in the general’s salute. “Imperator!” he shouted in a rush, then fell against Pompey, his damp and stained leather cuirass stinking foully of waterbrash and wine.

Varro was suddenly there on Sulla’s other side; together he and Pompey helped Lucius Cornelius Sulla back to his inglorious mule and shouldered him up until he sprawled upon its bare and dirty hide.

“He would insist on riding out to meet you as you asked,” Varro said, low—voiced. “Nothing I could say would stop him.”

Mounted on his Public Horse, Pompey turned, beckoned his troops to march, then ranged himself on the far side of Sulla’s mule from Varro, and rode on into Beneventum.

*

“I don’t believe it!” he cried to Varro after they had handed the almost insensible Sulla over to his keepers.

“He had a particularly bad night last night,” Varro said, unable to gauge the nature of Pompey’s emotions because he had never been privy to Pompey’s fantasies.

“A bad night? What do you mean?”

“It’s his skin, poor man. When he became so ill his doctors despaired of his life, they sent him to Aedepsus—a small spa some distance from Euboean Chalcis. The temple physicians there are said to be the finest in all Greece. And they saved him, it’s true! No ripe fruit, no honey, no bread, no cakes, no wine. But when they put him to soak in the spa waters, something in the skin of his face broke down. Ever since the early days at Aedepsus, he has suffered attacks of the most dreadful itching, and rips his face to raw and bleeding meat. He still eats no ripe fruit, no honey, no bread, no cakes. But wine gives him relief from the itching, so he drinks.” Varro sighed. “He drinks far too much.”

“Why his face? Why not his arms or legs?” Pompey asked, only half believing this tale.

“He had a bad sunburn on his face—don’t you remember how he always wore a shady hat whenever he was in the sun? But there had been some local ceremony to welcome him, he insisted on going through with—it despite his illness, and his vanity prompted him to wear a helmet instead of his hat. I presume it was the sunburn predisposed the skin of his face to break down,” said Varro, who was as fascinated as Pompey was revolted. “His whole head looks like a mulberry sprinkled with meal! Quite extraordinary!”

“You sound exactly like an unctuous Greek physician,” said Pompey, feeling his own face emerge from its plaster mask at last. “Where are we housed? Is it far? And what about my men?”

“I believe that Metellus Pius has gone to guide your men to their camp. We’re in a nice house not far down this street. If you come and break your fast now, we can ride out afterward and find your men.” Varro put his hand kindly on Pompey’s strong freckled arm, at a loss to know what was really wrong. There was no pity in Pompey’s nature, so much he had come to understand; why therefore was Pompey consumed with grief?

*

That night Sulla entertained the two new arrivals at a big dinner in his general’s house, its object to allow them to meet the other legates. Word had flown around Beneventum of Pompey’s advent—his youth, his beauty, his adoring troops. And Sulla’s legates were very put out, thought Varro in some amusement as he eyed their faces. They all looked as if their nursemaids had cruelly snatched a delicious honeycomb from their mouths, and when Sulla showed Pompey to the locus consularis on his own couch, then put no other man between them, the looks spoke murder. Not that Pompey cared! He made himself comfortable with unabashed pleasure and proceeded to talk to Sulla as if no one else was present.

Sulla was sober, and apparently not itching. His face had crusted over a little since the morning, he was calm and friendly, and obviously quite entranced with Pompey. I can’t be wrong about Pompey if Sulla sees it too, thought Varro.

Deeming it wiser at first to keep his gaze concentrated within his immediate vicinity rather than to inspect each man in the room in turn, Varro smiled at his couch companion, Appius Claudius Pulcher. A man he liked and esteemed. “Is Sulla still capable of leading us?” he asked.

“He’s as brilliant as he ever was,” said Appius Claudius. “If we can keep him sober he’ll eat Carbo, no matter how many troops Carbo can field.” Appius Claudius shivered, grimaced. “Can you feel the evil presences in this room, Varro?”

“Very definitely,” said Varro, though he didn’t think the kind of atmosphere he felt was what Appius Claudius meant.

“I’ve been studying the subject a little,” Appius Claudius proceeded to explain, “among the minor temples and cults at Delphi. There are fingers of power all around us—quite invisible, of course. Most people aren’t aware of them, but men like you and me, Varro, are hypersensitive to emanations from other places.”

“What other places?” asked Varro, startled.

“Underneath us. Above us. On all sides of us,” said Appius Claudius in sepulchral tones. “Fingers of power! I don’t know how else to explain what I mean. How can anyone describe invisible somethings only the hypersensitive can feel touching them? I’m not talking about the gods, or Olympus, or even Numina.…”

But the others in the room had lured Varro’s attention away from poor Appius Claudius, who continued to drone on happily while Varro assessed the quality of Sulla’s legates.

Philippus and Cethegus, the great tergiversators. Every time Fortune favored a new set of men, Philippus and Cethegus turned their togas inside out or back to the right side again, eager to serve the new masters of Rome; each of them had been doing it for thirty years. Philippus was the more straightforward of the two, had been consul after several fruitless tries and even became censor under Cinna and Carbo, the zenith of a man’s political career. Whereas Cethegus—a patrician Cornelius remotely related to Sulla—had remained in the background, preferring to wield his power by manipulating his fellow backbenchers in the Senate. They lay together talking loudly and ignoring everybody else.

Three young ones also lay together ignoring everybody else—what a lovely trio! Verres, Catilina and Ofella. Villains all, Varro was sure of it, though Ofella was more concerned about his dignitas than any future pickings. Of Verres and of Catilina there could be no doubt; the future pickings ruled them absolutely.

Another couch held three estimable, upright men—Mamercus, Metellus Pius and Varro Lucullus (an adopted Varro, actually the brother of Sulla’s loyalest follower, Lucullus). They patently disapproved of Pompey, and made no attempt to conceal it.

Mamercus was Sulla’s son-in-law, a quiet and steady man who had salvaged Sulla’s fortune and got his family safely to Greece.

Metellus Pius the Piglet and his quaestor Varro Lucullus had sailed from Liguria to Puteoli midway through April, and marched across Campania to join Sulla just before Carbo’s Senate mobilized the troops who might otherwise have stopped them. Until Pompey had appeared today, they had basked in the full radiance of Sulla’s grateful approval, for they had brought him two legions of battle—hardened soldiers. However, most of their attitude was founded in the who of Pompey, rather than in the what or even in the why. A Pompeius from northern Picenum? An upstart, a parvenu. A non—Roman! His father, nicknamed The Butcher because of the way he conducted his wars, might have achieved the consulship and great political power, but nothing could reconcile him and his to Metellus Pius or Varro Lucullus. No genuine Roman, of senatorial family or not, would have, at the age of twenty-two, taken it upon himself—absolutely illegally!—to bring the great patrician aristocrat Lucius Cornelius Sulla an army, and then demand to become, in effect, Sulla’s partner. The army which Metellus Pius and Varro Lucullus had brought Sulla automatically became his, to do with as he willed; had Sulla accepted it with thanks and then dismissed Metellus Pius and Varro Lucullus, they would perhaps have been angered, but they would have gone at once. Punctilious sticklers, both of them, thought Varro. So now they lay on the same couch glaring at Pompey because he had used the troops he had brought Sulla to elicit a top command neither his age nor his antecedents permitted. He had held Sulla to ransom.

Of all of them, however, by far the most intriguing to Varro was Marcus Licinius Crassus. In the autumn of the previous year he had arrived in Greece to offer Sulla two and a half thousand good Spanish soldiers, only to find his reception little warmer than the one he had received from Metellus Pius in Africa during the summer.

Most of the chilly welcome was due to the dramatic failure of a get—rich—quick scheme he and his friend the younger Titus Pomponius had engineered among investors in Cinna’s Rome. It had happened toward the end of the first year, which saw Cinna joined with Carbo in the consulship, when money was beginning rather coyly to appear again; news had come that the menace of King Mithridates was no more, that Sulla had negotiated the Treaty of Dardanus with him. Taking advantage of a sudden surge of optimism, Crassus and Titus Pomponius had offered shares in a new Asian speculation. The crash occurred when word came that Sulla had completely reorganized the finances of the Roman province of Asia, that there would be no tax—gathering bonanza after all.

Rather than stay in Rome to face hordes of irate creditors, both Crassus and Titus Pomponius had decamped. There was really only one place to go, one man to conciliate: Sulla. Titus Pomponius had seen this immediately, and gone to Athens with his huge fortune intact. Educated, urbane, something of a literary dilettante, personally charming, and just a trifle too fond of little boys, Titus Pomponius had soon come to an understanding with Sulla; but finding that he adored the atmosphere and style of life in Athens, he had chosen to remain there, given himself the cognomen of Atticus—Man of Athens.

Crassus was not so sure of himself, and had not seen that Sulla was his only alternative until much later than Atticus.

Circumstances had conspired to leave Marcus Licinius Crassus head of his family—and impoverished. The only money left belonged to Axia, the widow not only of his eldest brother, but also the widow of his middle brother. The size of her dowry had not been her sole attraction; she was pretty, vivacious, kindhearted and loving. Like Crassus’s mother, Vinuleia, she was a Sabine from Reate, and fairly closely related to Vinuleia at that. Her wealth came from the rosea rura, best pasture in all of Italy and breeding ground of fabulous stud donkeys which sold for enormous sums—sixty thousand sesterces was not an uncommon price for one such beast, potential sire of many sturdy army mules.

When Axia’s husband, the eldest Crassus son, Publius, was killed outside Grumentum during the Italian War, she was left a widow—and pregnant. In that tightly knit and frugal family, there seemed only one answer; after her ten months of mourning were over, Axia married Lucius, the second Crassus son. By whom she had no children. When he was murdered by Fimbria in the street outside his door, she was widowed again. As was Vinuleia, for Crassus the father, seeing his son cut down and knowing what his fate would be, killed himself on the spot.

At the time Marcus, the youngest Crassus son, was twenty-nine years old, the one whom his father (consul and censor in his day) had elected to keep at home in order to safeguard his name and bloodline. All the Crassus property was confiscated, including Vinuleia’s. But Axia’s family stood on excellent terms with Cinna, so her dowry wasn’t touched. And when her second ten—month period of mourning was over, Marcus Licinius Crassus married her and took her little son, his nephew Publius, as his own. Three times married to each of three brothers, Axia was known ever after as Tertulla—Little Three. The change in her name was her own suggestion; Axia had a harsh un—Latin ring to it, whereas Tertulla tripped off the tongue.

The glorious scheme Crassus and Atticus had concocted—which would have been a resounding success had Sulla not done the unexpected regarding the finances of Asia Province—shattered just as Crassus was beginning to see the family wealth increase again. And caused him to flee with a pittance in his purse, all his hopes destroyed. Behind him he left two women without a male protector, his mother and his wife. Tertulla bore his own son, Marcus, two months after he had gone.

But where to go? Spain, decided Crassus. In Spain lay a relic of past Crassus wealth. Years before, Crassus’s father had sailed to the Tin Isles, the Cassiterides, and negotiated an exclusive contract for himself to convey tin from the Cassiterides across northern Spain to the shores of the Middle Sea. Civil war in Italy had destroyed that, but Crassus had nothing left to lose; he fled to Nearer Spain, where a client of his father’s, one Vibius Paecianus, hid him in a cave until Crassus was sure that the consequences of his fiscal philandering were not going to follow him as far as Spain. He then emerged and began to knit his tin monopoly together again, after which he acquired some interests in the silver—lead mines of southern Spain.

All very well, but these activities could only prosper if the financial institutions and trading companies of Rome were made available to him again. Which meant he needed an ally more powerful than anyone he knew personally: he needed Sulla. But in order to woo Sulla (since he lacked the charm and the erudition possessed so plentifully by Titus Pomponius Atticus) he would have to bring Sulla a gift. And the only gift he could possibly offer was an army. This he raised among his father’s old clients; a mere five cohorts, but five well-trained and well-equipped cohorts.

His first port of call after he left Spain was Utica, in Africa Province, where he had heard Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, he whom Gaius Marius had called the Piglet, was still trying to hold on to his position as governor. He arrived early in the summer of the previous year, only to find that the Piglet—a pillar of Roman rectitude—was not amused by his commercial activities. Leaving the Piglet to make his own dispositions when his government fell, Crassus went on to Greece, and Sulla, who had accepted his gift of five Spanish cohorts, then proceeded to treat him coldly.

Now he sat with his small grey eyes fixed painfully upon Sulla, waiting for the slightest sign of approval, and obviously most put out to see Sulla interested only in Pompey. The cognomen of Crassus had been in the Famous Family of Licinius for many generations, but they still managed to breed true to it, Varro noted; it meant thickset (or perhaps, in the case of the first Licinius to be called Crassus, it might have meant intellectually dense?). Taller by far than he looked, Crassus was built on the massive lines of an ox, and had some of that animal’s impassive placidity in his rather expressionless face.

Varro gave the assembled men a final glance, and sighed. Yes, he had been right to spend most of his thoughts upon Crassus. They were all ambitious, most of them were probably capable, some of them were as ruthless as they were amoral, but—leaving Pompey and Sulla out of it, of course—Marcus Crassus was the man to watch in the future.

Walking back to their own house alongside a completely sober Pompey, Varro found himself very glad that he had yielded to Pompey’s exhortations and attached himself at first hand to this coming campaign.

“What did you and Sulla talk about?” he asked.

“Nothing earthshaking,” said Pompey.

“You kept your voices low enough.” ‘

“Yes, didn’t we?” Varro felt rather than saw Pompey’s grin. “He’s no fool, Sulla, even if he isn’t the man he used to be. If the rest of that sulky assemblage couldn’t hear what we said, how do they know we didn’t talk about them?”

“Did Sulla agree to be your partner in this enterprise?”

“I got to keep command of my own legions, which is all I wanted. He knows I haven’t given them to him, even on loan.”

“Was it discussed openly?’’

“I told you, the man is no fool,” said Pompey laconically. “Nothing much was said. That way, there is no agreement between us, and he is not bound.”

“You’re content with that?”

“Of course! He also knows he needs me,” said Pompey.

*

Sulla was up by dawn the next morning, and an hour later had his army on the march in the direction of Capua. By now he had accustomed himself to spurts of activity that coincided with the state of his face, for the itching was not perpetually there; rather, it tended to be cyclic. Having just emerged from a bout and its concomitant intake of wine, he knew that for some days he would have a little peace—provided he did absolutely nothing to trigger another cycle. This required a rigid policing of his hands, which could not be permitted to touch his face for any reason. Not until a man found himself in this predicament did he understand how many times his hands would go to his face without volition, without any awareness. And here he was with the weeping vesicles growing harder as they struggled to heal, and all the tickles, tingles, tiny movements of the skin that healing process involved. It was easiest on the first day, which was today, but as the days went on he would tend to forget, would reach up to scratch a perfectly natural itch of nose or cheek—and the whole ghastly business could start again. Would start again. So he had disciplined himself to get as much done as possible before the next outbreak, and then to drink himself insensible until it passed.

Oh, but it was difficult! So much to do, so much that had to be done, and he a shadow of the man he had been. Nothing had he accomplished without overcoming gigantic obstacles, but since the onset of that illness in Greece over a year ago he constantly found himself wondering why he bothered to continue. As Pompey had so obviously remarked, Sulla was no fool; he knew he had only a certain time left to live.

On a day like today, of course, just emerging from a bout of itching, he did understand why he bothered to continue: because he was the greatest man in a world unwilling to admit that. The Nabopolassar had seen it in him on the banks of the river Euphrates, and not even the gods could delude a Chaldaean seer. To be great beyond all other men, he understood on a day like today, meant a far greater degree of suffering too. He tried not to smile (a smile might disturb the healing process), thinking of his couch companion on the previous evening; now there was one who didn’t even begin to comprehend the nature of greatness!

Pompey the Great. Trust Sulla to have discovered already by what name he was known among his own people. A young man who actually thought that greatness did not have to be worked at, that greatness had been given him at birth and would never not be there. I wish with all my heart, Pompeius Magnus, thought Sulla, that I could live long enough to see who and what will bring you crashing down! A fascinating fellow, however. Most definitely a prodigy of some sort. He was not the stuff of a loyal subordinate, so much was sure. No, Pompey the Great was a rival. And saw himself as a rival. Already. At twenty-two. The veteran troops he had brought with him Sulla knew how to use; but how best to use Pompey the Great? Give him plenty of free rein to run with, certainly. Make sure he was not given a task he couldn’t do. Flatter him, exalt him, never prick his monumental conceit. Give him to understand that he is the user, and never let him see that he is the one being used. I will be dead long before he is brought crashing down, because while I am alive, I will make sure no one does that to him. He’s far too useful. Too … Valuable.

The mule upon which Sulla rode squealed, tossed its head in agreement. But, ever mindful of his face, Sulla did not smile at the mule’s sagacity. He was waiting. Waiting for a jar of ointment and a recipe from which to make further jars of ointment. Almost ten years ago he had first experienced this skin disease, on his way back from the Euphrates. How satisfying that expedition had been!

His son had come along, Julilla’s son who in his adolescence had turned out to be the friend and confidant Sulla had never owned before. The perfect participant in a perfect relationship. How they had talked! About anything and everything. The boy had been able to forgive his father so many things Sulla had never been able to forgive himself—oh, not murders and other necessary practicalities, they were just the things a man’s life forced him to do. But emotional mistakes, weaknesses of the mind dictated by longings and inclinations reason shouted were stupid, futile. How gravely Young Sulla had listened, how completely had he, so short in years, understood. Comforted. Produced excuses which at the time had even seemed to hold water. And Sulla’s rather barren world had glowed, expanded, promised a depth and dimension only this beloved son could give it. Then, safely home from the journey beyond the Euphrates and Roman experience, Young Sulla had died. Just like that. Over and done with in two tiny little insignificant days. Gone the friend, gone the confidant. Gone the beloved son.

The tears stung, welled up—no! No! He could not weep, must not weep! Let one drop trickle down his cheek, and the itchy torment would begin. Ointment. He must concentrate upon the idea of the ointment. Morsimus had found it in some forgotten village somewhere near the Pyramus River of Cilicia Pedia, and it had soothed, healed him.

Six months ago he had sent to Morsimus, now an ethnarch in Tarsus, and begged him to find that ointment, even if he had to search every settlement in Cilicia Pedia. Could he but find it again—and, more importantly, its recipe—his skin would return to normal. And in the meantime, he waited. Suffered. Became ever greater. Do you hear that, Pompey the Great?

He turned in his saddle and beckoned to where behind him rode Metellus Pius the Piglet and Marcus Crassus (Pompey the Great was bringing up the rear at the head of his three legions).

“I have a problem,” he said when Metellus Pius and Crassus drew level with him.

“Who?” asked the Piglet shrewdly.

“Oh, very good! Our esteemed Philippus,” said Sulla, no expression creasing his face.

“Well, even if we didn’t have Appius Claudius along, Lucius Philippus would present a problem,” said Crassus, the abacus of his mind clicking from unum to duo, ”but there’s no denying Appius Claudius makes it worse. You’d think the fact that Appius Claudius is Philippus’s uncle would have kept him from expelling Appius Claudius from the Senate, but it didn’t.”

“Probably because nephew Philippus is some years older than uncle Appius Claudius,” said Sulla, entertained by this opinion.

“What exactly do you want to do with the problem?” asked Metellus Pius, unwilling to let his companions drift off into the complexities of Roman upper—class blood relationships.

“I know what I’d like to do, but whether or not it’s even possible rests with you, Crassus,” said Sulla.

Crassus blinked. “How could it affect me?”

Tipping back his shady straw hat, Sulla looked at his legate with a little more warmth in his eyes than of yore; and Crassus, in spite of himself, felt an uplift in the region of his breast. Sulla was deferring to him!

“It’s all very well to be marching along buying grain and foodstuffs from the local farmers,” Sulla began, his words a trifle slurred these days because of his lack of teeth, “but by the end of summer we will need a harvest I can ship from one place. It doesn’t have to be a harvest the size of Sicily’s or Africa’s, but it does have to provide the staple for my army. And I am confident that my army will increase in size as time goes on.”

“Surely,” said Metellus Pius carefully, “by the autumn we’ll have all the grain we need from Sicily and Africa. By the autumn we will have taken Rome.”

“I doubt that.”

“But why? Rome’s rotting from within!”

Sulla sighed, his lips flapping. “Piglet dear, if I am to help Rome recover, then I have to give Rome a chance to decide in my favor peacefully. Now that is not going to happen by the autumn. So I can’t appear too threatening, I can’t march at the double up the Via Latina and attack Rome the way Cinna and Marius descended upon her after I left for the east. When I marched on Rome the first time, I had surprise on my side. No one believed I would. So no one opposed me except a few slaves and mercenaries belonging to Gaius Marius. But this time is different. Everyone expects me to march on Rome. If I do that too quickly, I’ll never win. Oh, Rome would fall! But every nest of insurgents, every school of opposition would harden. It would take me longer than I have left to live to put resistance down. I can’t afford the time or the effort. So I’ll go very slowly toward Rome.”

Metellus Pius digested this, and saw the sense of it. With a gladness he couldn’t quite conceal from those glacial eyes in their sore sockets. Wisdom was not a quality he associated with any Roman nobleman; Roman noblemen were too political in their thinking to be wise. Everything was of the moment, seen in the short term. Even Scaurus Princeps Senatus, for all his experience and his vast auctoritas, had not been wise. Any more than had the Piglet’s own father, Metellus Numidicus. Brave. Fearless. Determined. Unyielding of principle. But never wise. So it cheered the Piglet immensely to know that he rode down the long road to Rome with a wise man, for he was a Caecilius Metellus and he had a foot in both camps, despite his personal choice of Sulla. If there was any aspect of this undertaking from which he shrank, it was the knowledge that—try though he might to avoid it—he would inevitably end in ruining a good proportion of his blood or marital relations. Therefore he appreciated the wisdom of advancing slowly upon Rome; some of the Caecilii Metelli who at the moment supported Carbo might see the error of their ways before it was too late.

Of course Sulla knew exactly how the Piglet’s mind was working, and let him finish his thoughts in peace. His own thoughts were upon his task as he stared between the mournful flops of his mule’s ears. I am back in Italy and soon Campania, that cornucopia of all the good things from the earth, will loom in the distance—green, rolling, soft of mountain, sweet of water. And if I deliberately exclude Rome from my inner gaze, Rome will not eat at me the way this itching does. Rome will be mine. But, though my crimes have been many and my contrition none, I have never liked so much as the idea of rape. Better by far that Rome comes to me consenting, than that I am forced to rape her….

“You may have noticed that ever since I landed in Brundisium I have been sending written letters to all the leaders of the old Italian Allies, promising them that I will see every last Italian properly enrolled as a citizen of Rome according to the laws and treaties negotiated at the end of the Italian War. I will even see them distributed across the full gamut of the thirty-five tribes. Believe me, Piglet, I will bend like a strand of spider’s web in the wind before I attack Rome!”

“What have the Italians to do with Rome?” asked Metellus Pius, who had never been in favor of granting the full Roman citizenship to the Italians, and had secretly applauded Philippus as censor because Philippus and his fellow censor, Perperna, had avoided enrolling the Italians as Roman citizens.

“Between Pompeius and me, we’ve marched through much of the territory which fought against Rome without encountering anything beyond welcome—and perhaps hope that I will change the situation in Rome concerning their citizenships. Italian support will be a help to me in persuading Rome to yield peacefully.”

“I doubt it,” said Metellus Pius stiffly, “but I daresay you know what you’re doing. Let’s get back to the subject of Philippus, who is a problem.”

“Certainly!” said Sulla, eyes dancing.

“What has Philippus to do with me?” asked Crassus, deeming it high time he intruded himself into what had become a duet.

“I have to get rid of him, Marcus Crassus. But as painlessly as possible, given the fact that somehow he has managed to turn himself into a hallowed Roman institution.”

“That’s because he has become everybody’s ideal of the dedicated political contortionist,” said the Piglet, grinning.

“Not a bad description,” said Sulla, nodding instead of trying to smile. “Now, my big and ostensibly placid friend Marcus Crassus, I am going to ask you a question. I require an honest answer. Given your sad reputation, are you capable of giving me an honest answer?’’

This sally did not appear even to dent Crassus’s oxlike composure. “I will do my best, Lucius Cornelius.”

“Are you passionately attached to your Spanish troops?”

“Considering that you keep making me find provisions for them, no, I am not,” said Crassus.

“Good! Would you part with them?”

“If you think we can do without them, yes.”

“Good! Then with your splendidly phlegmatic consent, my dear Marcus, I’ll bring down several quarry with the same arrow. It is my intention to give your Spaniards to Philippus—he can take and hold Sardinia for me. When the Sardinian harvest comes in, he will send all of it to me,” said Sulla. He reached for the hide flask of pale sour wine tied to one horn of his saddle, lifted it, and squirted liquid expertly into his gummy mouth; not a drop fell on his face.

“Philippus will refuse to go,” said Metellus Pius flatly.

“No, he won’t. He’ll love the commission,” said Sulla,capping the birdlike neck of his wineskin. “He’ll be the full and undisputed master of all he surveys, and the Sardinian brigands will greet him like a brother. He makes every last one of them look virtuous.”

Doubt began to gnaw at Crassus, who rumbled deeply in his throat, but said no word.

“Wondering what you’ll do without troops to command?”

“Something like that,” said Crassus cautiously.

“You could make yourself very useful to me,” said Sulla in casual tones.

“How?”

“Your mother and your wife are both from prominent Sabine families. How about going to Reate and starting to recruit for me? You could commence there, and finish among the Marsi.” Out went Sulla’s hand, clasped the heavy wrist of Crassus. “Believe me, Marcus Crassus, in the spring of next year there will be much military work for you to do, and good troops—Italian, if not Roman—for you to command.”

“That suits me,” said Crassus. “It’s a deal.”

“Oh, if only everything could be solved so easily and so well!” cried Sulla, reaching once more for his wineskin.

Crassus and Metellus Pius exchanged glances across the bent head of silly artificial curls; he might say he drank to ease the itching, but the truth appeared more to be that nowadays Sulla couldn’t go for very long without wetting his whistle. Somewhere down the nightmare alley of his physical torments, he had embraced his palliative with a permanent and enduring love. But did he know it? Or did he not?

Had they found the courage to ask him, Sulla would have told them readily. Yes, he knew it. Nor did he care who else knew it, including the fact that his deceptively weak-looking vintage was actually strongly fortified. Forbidden bread, honey, fruit and cakes, little in his diet did he truly like. The physicians of Aedepsus had been right to remove all those tasty things from his food intake, of that he had no doubt. When he had come to them, he knew he was dying. First he had endured an insatiable craving for sweet and starchy things, and put on so much weight that even his mule had complained about the burden of carrying him; then he began to experience numbness and tingling in both feet, burnings and pains too as time went on, so that the moment he lay down to sleep, his wretched feet refused to let him. The sensations crept into his ankles and lower legs, sleep became harder and harder to find. So he added a heavy; very sweet and fortified wine to his customary fare, and used it to drug himself into sleeping. Until the day when he had found himself sweating, gasping—and losing weight so quickly that he could almost see himself disappearing. He drank flagons of water one after the other, yet still was thirsty. And—most terrifying of all!—his eyes began to fail.

Most of that had disappeared or greatly eased after he went to Aedepsus. Of his face he wouldn’t think, he who had been so beautiful in his youth that men had made absolute fools of themselves, so beautiful after he attained maturity that women had made absolute fools of themselves. But one thing which had not disappeared was his need to drink wine. Yielding to the inevitable, the priest—physicians of Aedepsus had persuaded him to exchange his sweet fortified wine for the sourest vintages available, and over the months since, he had come to prefer his wine so dry it made him grimace. When the itch was not upon him he kept the amount he drank under some sort of control, in that he didn’t let it interfere with his thought processes. He just drank enough to improve them—or so he told himself.

“I’ll keep Ofella and Catilina with me,” he said to Crassus and Metellus Pius, stoppering up the flask again. “However, Verres is the epitome of his name—an insatiably greedy boar. I think I will send him back to Beneventum, for the time being at least. He can organize supplies and keep an eye on our rear.”

The Piglet giggled. “He might like that, the honey—boy!”

This provoked a brief grin in Crassus. “What about yon Cethegus?” he asked, legs aching from hanging down limply; they were very heavy legs. He shifted his weight a little.

“Cethegus I shall retain for the moment,” said Sulla. His hand strayed toward the wine, then was snatched away. “He can look after things in Campania.”

*

Just before his army crossed the river Volturnus near the town of Casilinum, Sulla sent six envoys to negotiate with Gaius Norbanus, the more capable of Carbo’s two tame consuls. Norbanus had taken eight legions and drawn himself up to defend Capua, but when Sulla’s envoys appeared carrying a flag of truce, he arrested them without a hearing. He then marched his eight legions out onto the Capuan plain right beneath the slopes of Mount Tifata. Irritated by the unethical treatment meted out to his envoys, Sulla proceeded to teach Norbanus a lesson he would not forget. Down the flank of Mount Tifata Sulla led his troops at a run, hurled them on the unsuspecting Norbanus. Defeated before the battle had really begun, Norbanus retreated inside Capua, where he sorted out his panicked men, sent two legions to hold the port of Neapolis for Carbo’s Rome, and prepared himself to withstand a siege.

Thanks to the cleverness of a tribune of the plebs, Marcus Junius Brutus, Capua was very much disposed to like the present government in Rome; earlier in the year, Brutus had brought in a law giving Capua the status of a Roman city, and this, after centuries of being punished by Rome for various insurrections, had pleased Capua mightily. Norbanus had therefore no need to worry that Capua might grow tired of playing host to him and his army. Capua was used to playing host to Roman legions.

“We have Puteoli, so we don’t need Neapolis,” said Sulla to Pompey and Metellus Pius as they rode toward Teanum Sidicinum, “and we can do without Capua because we hold Beneventum. I must have had a feeling when I left Gaius Verres there.” He stopped for a moment, thought about something, nodded as if to answer his thought. “Cethegus can have a new job. Legate in charge of all my supply columns. That will tax his diplomacy!”

“This,” said Pompey in disgruntled tones, “is a very slow kind of war. Why aren’t we marching on Rome?”

The face Sulla turned to him was, given its limitations, a kind one. “Patience, Pompeius! In martial skills you need no tuition, but your political skills are nonexistent. If the rest of this year teaches you nothing else, it will serve as a lesson on political manipulation. Before ever we contemplate marching on Rome, we have first to show Rome that she cannot win under her present government. Then, if she proves to be a sensible lady, she will come to us and offer herself to us freely.”

“What if she doesn’t?” asked Pompey, unaware that Sulla had already been through this with Metellus Pius and Crassus.

“Time will tell” was all Sulla would say.

They had bypassed Capua as if Norbanus inside it did not exist, and rolled on toward the second of Rome’s consular armies, under the command of Scipio Asiagenus and his senior legate, Quintus Sertorius. The little and very prosperous Campanian towns around Sulla did not so much capitulate as greet him with open arms, for they knew him well; Sulla had commanded Rome’s armies in this part of Italy for most of the duration of the Italian War.

Scipio Asiagenus was camped between Teanum Sidicinum and Cales, where a small tributary of the Volturnus, fed by springs, provided a great deal of slightly effervescent water; even in summer its mild warmth was delightful.

“This,” said Sulla, “will be an excellent winter camp!” And sat himself and his army down on the opposite bank of the streamlet from his adversary. The cavalry were sent back to Beneventum under the charge of Cethegus, while Sulla himself gave a new party of envoys explicit instructions on how to proceed in negotiating a truce with Scipio Asiagenus.

“He’s not an old client of Gaius Marius’s, so he’ll be much easier to deal with than Norbanus,” said Sulla to Metellus Pius and Pompey. His face was still in remission and his intake of wine was somewhat less than on the journey from Beneventum, which meant that his mood was cheerful and his mind very clear.

“Maybe,” said the Piglet, looking doubtful. “If it were only Scipio, I’d agree wholeheartedly. But he has Quintus Sertorius with him, and you know what that means, Lucius Cornelius.”

“Trouble,” said Sulla, sounding unworried.

“Ought you not be thinking how to render Sertorius impotent?”

“I won’t need to do that, Piglet dear. Scipio will do it for me.” He pointed with a stick toward the place where a sharp bend in the little river drew his camp’s boundary very close to the boundary of Scipio’s camp on the far shore. “Can your veterans dig, Gnaeus Pompeius?”

Pompey blinked. “With the best!”

“Good. Then while the rest are finishing off the winter fortifications, your fellows can excavate the bank outside our wall, and make a great big swimming pool,” said Sulla blandly.

“What a terrific idea!” said Pompey with equal sangfroid, and smiled. “I’ll get them onto it straightaway.” He paused, took the stick from Sulla and pointed it at the far bank. “If it’s all right with you, General, I’ll break down the bank and concentrate on widening the river, rather than make a separate swimming hole. And I think it would be very nice for our chaps if I roofed at least a part of it over—less chilly later on.”

“Good thinking! Do that,” said Sulla cordially, and stood watching Pompey stride purposefully away.

“What was all that about?’’ asked Metellus Pius, frowning; he hated to see Sulla so affable to that conceited young prig!

“He knew,” said Sulla cryptically.

“Well, I don’t!” said the Piglet crossly. “Enlighten me!”

“Fraternization, Piglet dear! Do you think Scipio’s men are going to be able to resist Pompeius’s winter spa? Even in summer? After all, our men are Roman soldiers too. There is nothing like a truly pleasurable activity shared in common to breed friendship. The moment Pompeius’s pool is finished, there will be as many of Scipio’s men enjoying it as ours. And they’ll all get chatty in no time—same jokes, same complaints, same sort of life. It’s my bet we won’t have to fight a battle.”

“And he understood that from the little you said?”

“Absolutely.”

“I’m surprised he agreed to help! He’s after a battle.”

“True. But he’s got my measure, Pius, and he knows he will not get a battle this side of spring. It’s no part of Pompeius’s strategy to annoy me, you know. He needs me just as much as I need him,” said Sulla, and laughed softly without moving his face.

“He strikes me as the sort who might prematurely decide that he doesn’t need you.”

“Then you mistake him.”

*

Three days later, Sulla and Scipio Asiagenus parleyed on the road between Teanum and Cales, and agreed to an armistice. About this moment Pompey finished his swimming hole, and—typically methodical—after publishing a roster for its use that allowed sufficient space for invaders from across the river, threw it open for troop recreation. Within two more days the coming and going between the two camps was so great that,

“We may as well abandon any pretense that we’re on opposite sides,” said Quintus Sertorius to his commander.

Scipio Asiagenus looked surprised. “What harm does it do?” he asked gently.

The one eye Sertorius was left with rolled toward the sky. Always a big man, his physique had set with the coming of his middle thirties into its final mold—thick—necked, bull—like, formidable. And in some ways this was a pity, for it endowed Sertorius with a bovine look entirely at variance with the power and quality of his mind. He was Gaius Marius’s cousin, and had inherited far more of Marius’s personal and military brilliance than had, for instance, Marius’s son. The eye had been obliterated in a skirmish just before the Siege of Rome, but as it was his left one and he was right—handed, its loss had not slowed him down as a fighter. Scar tissue had turned his pleasant face into something of a caricature, in that its right side was still most pleasant while its left leered a horrible contradiction.

So it was that Scipio underestimated him, did not respect or understand him. And looked at him now in surprise.

Sertorius tried. “Asiagenus, think! How well do you feel our men will fight for us if they’re allowed to get too friendly with the enemy?”

“They’ll fight because they’re ordered to fight.”

“I don’t agree. Why do you think Sulla built his swimming hole, if not to suborn our troops? He didn’t do it for the sake of his own men! It’s a trap, and you’re falling into it!”

“We are under a truce, and the other side is as Roman as we are,” said Scipio Asiagenus stubbornly.

“The other side is led by a man you ought to fear as if he and his army had been sown from the dragon’s teeth! You can’t give him one single little inch, Asiagenus. If you do, he will end in taking all the miles between here and Rome.”

“You exaggerate,” said Scipio stiffly.

“You’re a fool!” snarled Sertorius, unable not to say it.

But Scipio was not impressed by the display of temper either. He yawned, scratched his chin, looked down at his beautifully manicured nails. Then he looked up at Sertorius looming over him, and smiled sweetly. “Do go away!” he said.

“I will that! Right away!” Sertorius snapped. “Maybe Gaius Norbanus can make you see sense!”

“Give him my regards,” Scipio called after him, then went back to studying his nails.

So Quintus Sertorius rode for Capua at the gallop, and there found a man more to his taste than Scipio Asiagenus. The loyalest of Marians, Norbanus was no fanatical adherent of Carbo’s; after the death of Cinna, he had only persisted in his allegiance because he loathed Sulla far more than he did Carbo.

“You mean that chinless wonder of an aristocrat actually has concluded an armistice with Sulla?” asked Norbanus, voice squeaking as it uttered that detested name.

“He certainly has. And he’s permitting his men to fraternize with the enemy,” said Sertorius steadily.

“Why did I have to be saddled with a colleague as stupid as Asiagenus?” wailed Norbanus, then shrugged. “Well, that is what our Rome is reduced to, Quintus Sertorius. I’ll send him a nasty message which he will ignore, but I suggest you don’t return to him. I hate to think of you as a captive of Sulla’s—he’d find a way to murder you. Find something to do that will annoy Sulla.”