Metellus Pius had marched for the Adriatic coast with his own two legions (under the command of his legate Varro Lucullus), six legions which had belonged to Scipio, the three legions which belonged to Pompey, and those five thousand horse troopers Sulla had given to Pompey.

Of course Varro the Sabine traveled with Pompey, a ready and sympathetic ear (not to mention a ready and sympathetic pen!) tuned to receive Pompey’s thoughts.

“I must put myself on better terms with Crassus,” said Pompey to him as they moved through Picenum. “Metellus Pius and Varro Lucullus are easy—and anyway, I quite like them. But Crassus is a surly brute. More formidable by far. I need him on my side.”

Astride a pony, Varro looked a long way up to Pompey on his big white Public Horse. “I do believe you’ve learned something during the course of a winter spent with Sulla!” he said, genuinely amazed. “I never thought to hear you speak of conciliating any man—with the exception of Sulla, naturally.”

“Yes, I have learned,” admitted Pompey magnanimously. His beautiful white teeth flashed in a smile of pure affection. “Come now, Varro! I know I’m well on my way to becoming Sulla’s most valued helper, but I am capable of understanding that Sulla needs other men than me! Though you may be right,” he went on thoughtfully. “This is the first time in my life that I’ve dealt with any other commander-in-chief than my father. I think my father was a very great soldier. But he cared for nothing aside from his lands. Sulla is different.”

“In what way?” asked Varro curiously.

“He cares nothing for most things—including all of us he calls his legates, or colleagues, or whatever name he considers judicious at the time. I don’t know that he even cares for Rome. Whatever he does care for, it isn’t material. Money, lands—even the size of his auctoritas or the quality of his public reputation. No, they don’t matter to Sulla.”

“Then what does?’’ Varro asked, fascinated with the phenomenon of a Pompey who could see further than himself.

“Perhaps his dignitas alone,” Pompey answered.

Varro turned this over carefully. Could Pompey be right?

Dignitas! The most intangible of all a Roman nobleman’s possessions, that was dignitas. His auctoritas was his clout, his measure of public influence, his ability to sway public opinion and public bodies from Senate to priests to the Treasury.

Dignitas was different. It was intensely personal and very private, yet it extended into all parameters of a man’s public life. So hard to define! That, of course, was why there was a word for it. Dignitas was … a man’s personal degree of impressiveness … of glory? Dignitas summed up what a man was, as a man and as a leader of his society. It was the total of his pride, his integrity, his word, his intelligence, his deeds, his ability, his knowledge, his standing, his worth as a man.... Dignitas survived a man’s death, it was the only way he could triumph over death. Yes, that was the best definition. Dignitas was a man’s triumph over the extinction of his physical being. And seen in that light, Varro thought Pompey absolutely correct. If anything mattered to Sulla, it was his dignitas. He had said he would beat Mithridates. He had said he would come back to Italy and secure his vindication. He had said that he would restore the Republic in its old, traditional form. And having said these things, he would do them. Did he not, his dignitas would be diminished; in outlawry and official odium there could be no dignitas. So from out of himself he would find the strength to make his word good. When he had made his word good, he would be satisfied. Until he had, Sulla could not rest. Would not rest.

“In saying that,” Varro said, “you have awarded Sulla the ultimate accolade.”

The bright blue eyes went blank. “Huh?”

“I mean,” said Varro patiently, “that you have demonstrated to me that Sulla cannot lose. He’s fighting for something Carbo doesn’t even understand.”

“Oh, yes! Yes, definitely!” said Pompey cheerfully.

They were almost to the river Aesis, in the heart of Pompey’s own fief again. The brash youth of last year had not vanished, but sat now amid a branching superstructure of fresh, stimulating experiences; in other words, Pompey had grown. In fact, he grew a little more each day. Sulla’s gift of cavalry command had interested Pompey in a type of military activity he had never before seriously considered. That of course was Roman. Romans believed in the foot soldier, and to some extent had come to believe the horse soldier was more decorative than useful, more a nuisance than an asset. Varro was convinced that the only reason Romans employed cavalry was because the enemy did.

Once upon a time, in the days of the Kings of Rome and in the very early years of the Republic, the horse soldier had formed the military elite, was the spearhead of a Roman army. Out of this had grown the class of knights—the Ordo Equester, as Gaius Gracchus had called it. Horses had been hugely expensive—too expensive for many men to buy privately. Out of that had grown the custom of the Public Horse, the knight’s mount bought and paid for by the State.

Now, a long way down the road from those days, the Roman horse soldier had ceased to exist except in social and economic terms. The knight—businessman or landowner that he was, member of the First Class of the Centuries—was the horse soldier’s Roman relic. And still to this day, the State bought the eighteen hundred most senior knights their horses.

Addicted to exploring the winding lanes of thought, Varro saw that he was losing the point of his original reflection, and drew himself resolutely back onto thought’s main road. Pompey and his interest in the cavalry. Not Roman in manpower anymore. These were Sulla’s troopers he had brought from Greece with him, and therefore contained no Gauls; had they been recruited in Italy, they would have been almost entirely Gallic, drawn from the rolling pastures on the far side of the Padus in Italian Gaul, or from the great valley of the Rhodanus in Gaul-across-the-Alps. As it was, Sulla’s men were mostly Thracians, admixed with a few hundred Galatians. Good fighters, and as loyal as could be expected of men who were not themselves Roman. In the Roman army they had auxiliary status, and some of them might be rewarded at the end of a hard—won campaign with the full Roman citizenship, or a piece of land.

All the way from Teanum Sidicinum, Pompey had busied himself going among these men in their leather trousers and leather jerkins, with their little round shields and their long lances; their long swords were more suitable for slashing from the height of a horse’s back than the short sword of the infantryman. At least Pompey had the capacity to think, Varro told himself as they rode steadily toward the Aesis. He was discovering the qualities of horsemen—soldiers and turning over the possibilities. Planning. Seeing if there was any way their performance or equipage might be improved. They were formed into regiments of five hundred men, each regiment consisting of ten squadrons of fifty men, and they were led by their own officers; the only Roman who commanded them was the overall general of cavalry. In this case, Pompey. Very much involved, very fascinated—and very determined to lead them with a flair and competence not usually present in a Roman. If Varro privately thought that a part of Pompey’s interest stemmed from his large dollop of Gallic blood, he was wise enough never to indicate to Pompey that such was his theory.

How extraordinary! Here they were, the Aesis in sight, and Pompey’s old camp before them. Back where they had begun, as if all the miles between had been nothing. A journey to see an old man with no teeth and no hair, distinguished only by a couple of minor battles and a lot of marching.

“I wonder,” said Varro, musing, “if the men ever ask themselves what it’s all about?”

Pompey blinked, turned his head sideways. “What a strange question! Why should they ask themselves anything? It’s all done for them. I do it all for them! All they have to do is as they’re told.” And he grimaced at the revolutionary thought that so many as one of Pompey Strabo’s veterans might think.

But Varro was not to be put off. “Come now, Magnus! They are men—like us in that respect, if in no other. And being men, they are endowed with thought. Even if a lot of them can’t read or write. It’s one thing never to question orders, quite another not to ask what it’s all about.”

“I don’t see that,” said Pompey, who genuinely didn’t.

“Magnus, I call the phenomenon human curiosity! It is in a man’s nature to ask himself the reason why! Even if he is a Picentine ranker who has never been to Rome and doesn’t understand the difference between Rome and Italy. We have just been to Teanum and back. There’s our old camp down there. Don’t you think that some of them at least must be asking themselves what we went to Teanum for, and why we’ve come back in less than a year?”

“Oh, they know that!” said Pompey impatiently. “Besides, they’re veterans. If they had a thousand sesterces for every mile they’ve marched during the past ten years, they’d be able to live on the Palatine and breed pretty fish. Even if they did piss in the fountain and shit in the cook’s herb garden! Varro, you are such an original! You never cease to amaze me—the things that chew at you!” Pompey kicked his Public Horse in the ribs and began to gallop down the last slope. Suddenly he laughed uproariously, waved his hands in the air; his words floated back quite clearly. “Last one in’s a rotten egg!”

Oh, you child! said Varro to himself. What am I doing here? What use can I possibly be? It’s all a game, a grand and magnificent adventure.

*

Perhaps it was, but late that night Metellus Pius called a meeting with his three legates, and Varro as always accompanied Pompey. The atmosphere was excited: there had been news.

“Carbo isn’t far away,” said the Piglet. He paused to consider what he had said, and modified it. “At least, Carrinas is, and Censorinus is rapidly catching him up. Apparently Carbo thought eight legions would be enough to halt our progress, then he discovered the size of our army, and sent Censorinus with another four legions. They’ll reach the Aesis ahead of us, and it’s there we’ll have to meet them.”

“Where’s Carbo himself?” asked Marcus Crassus.

“Still in Ariminum. I imagine he’s waiting to see what Sulla intends to do.”

“And how Young Marius will fare,” said Pompey.

“True,” agreed the Piglet, raising his brows. “However, it isn’t our job to worry about that. Our job is to make Carbo hop. Pompeius, this is your purlieu. Should we bring Carrinas across the river, or keep him on the far side?”

“It doesn’t really matter,” said Pompey coolly. “The banks are much the same. Plenty of room to deploy, some tree cover, good level ground for an all—out contest if we can bring it on.” He looked angelic, and said sweetly, “The decision belongs to you, Pius. I’m only your legate.”

“Well, since we’re trying to get to Ariminum, it makes more sense to get our men to the far side,” said Metellus Pius, quite unruffled. “If we do force Carrinas to retreat, we don’t want to have to cross the Aesis in pursuit. The report indicates that we have a huge advantage in cavalry. Provided that you think the terrain and the river will allow it, Pompeius, I would like you to spearhead the crossing and keep your horse—troopers between the enemy and our infantry. Then I’ll wheel our infantry on the far bank, you peel your cavalry back out of the way, and we’ll attack. There’s not much we can do in terms of subterfuge. It will be a straight battle. However, if you can swing your cavalry around behind the enemy after I’ve engaged him from the front, we’ll roll Carrinas and Censorinus up.”

No one objected to this strategy, which was sufficiently loose to indicate that Metellus Pius had some talent as a general. When it was suggested that Varro Lucullus should command Pompey’s three legions of veterans, thereby allowing Pompey full license with his cavalry, Pompey agreed without a qualm.

“I’ll lead the center,” said Metellus Pius in conclusion, “with Crassus leading the right, and Varro Lucullus the left.”

Since the day was fine and the ground was not too wet, things went very much as Metellus Pius had planned. Pompey held the crossing easily, and the infantry engagement which followed demonstrated the great advantage veteran troops bestowed upon a general in battle. Though Scipio’s legions were raw enough, Varro Lucullus and Crassus led the five veteran legions superbly, and their confidence spilled over onto Scipio’s men. Carrinas and Censorinus had no veteran troops, and went down without extending Metellus Pius too severely. The end result would have been a rout had Pompey managed to fall upon the enemy rear, but as he skirted the field to do so, he encountered a new factor. Carbo had arrived with six more legions—and three thousand horse to contest Pompey’s progress.

Carrinas and Censorinus managed to draw off without losing more than three or four thousand men, then camped next to Carbo a scant mile beyond the battlefield. The advance of Metellus Pius and his legates ground to a halt.

“We will go back to your original camp south of the river,” said Metellus Pius with crisp decision. “I would rather they think us too cautious to proceed, and I also think it behooves us to keep a fair distance between us and them.”

Despite the disappointing outcome of the day’s conflict, spirits were high among the men, and quite high in the command tent when Pompey, Crassus and Varro Lucullus met their general at dusk. The table was covered with maps, a slight disorder indicating that the Piglet had been poring over them closely.

“All right,” he said, standing behind the table, “I want you to look at this, and see how best we can outflank Carbo.”

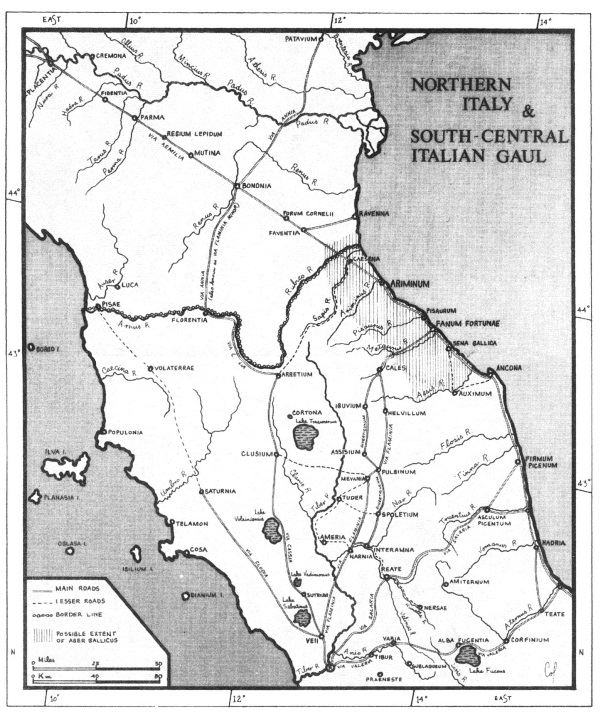

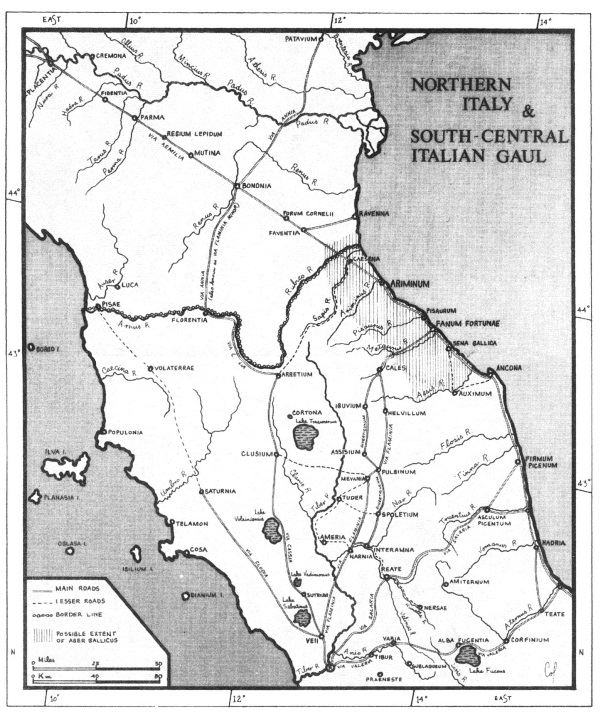

They clustered around, Varro Lucullus holding a five-flamed lamp above the carefully inked sheepskin. The map displayed the Adriatic coastline between Ancona and Ravenna, together with inland territory extending beyond the crest of the Apennines.

“We’re here,” said the Piglet, finger on a spot below the Aesis. “The next big river onward is the Metaurus, a treacherous crossing. All this land is Ager Gallicus—here—and here—Ariminum at the northward end of it—some rivers, but none according to this difficult to ford. Until we come to this one—between Ariminum and Ravenna, see? The Rubico, our natural border with Italian Gaul.” All these features were lightly touched; the Piglet was methodical. “It’s fairly obvious why Carbo has put himself in Ariminum. He can move up the Via Aemilia into Italian Gaul proper—he can go down the Sapis road to the Via Cassia at Arretium and threaten Rome from the upper Tiber valley—he can reach the Via Flaminia and Rome that way—he can march down the Adriatic into Picenum, and if necessary into Campania through Apulia and Samnium.”

“Then we have to dislodge him,” said Crassus, stating the obvious. “It’s possible.”

“But there is a hitch,” said Metellus Pius, frowning. “It seems Carbo is not entirely confined to Ariminum anymore. He’s done something very shrewd by sending eight legions under Gaius Norbanus up the Via Aemilia to Forum Cornelii—see? Not far beyond Faventia. Now that is not a great distance from Ariminum—perhaps forty miles.”

“Which means he could get those eight legions back to Ariminum in one hard day’s march if he had to,” said Pompey.

“Yes. Or get them to Arretium or Placentia in two or three days,” said Varro Lucullus, who never lost sight of the overall concept. “We have Carbo himself sitting on the other side of the Aesis with Carrinas and Censorinus—and eighteen legions plus three thousand cavalry. There are eight more legions in Forum Cornelii with Norbanus, and another four garrisoning Ariminum in company with several thousand more cavalry.”

“I need a grand strategy before I go one more inch,” said Metellus Pius, looking at his legates.

“The grand strategy is easy,” said Crassus, the abacus clicking away inside his mind. “We have to prevent Carbo’s recombining with Norbanus, separate Carbo from Carrinas and Censorinus, and Carrinas from Censorinus. Prevent every one of them from recombining. Just as Sulla said. Fragmentation.”

“One of us—probably me—will have to get five legions to the far side of Ariminum, then cut Norbanus off and make a bid to take Italian Gaul,” said Metellus Pius, frowning. “Not an easy thing to do.”

“It is easy,” said Pompey eagerly. “Look—here’s Ancona, the second—best harbor on the Adriatic. At this time of year it’s full of ships waiting on the westerlies to sail for the east and a summer’s trading. If you took your five legions to Ancona, Pius, you could embark them on those ships and sail to Ravenna. It’s a sweet voyage, you’d never need to be out of sight of land, and there won’t be any storms. It’s no more than a hundred miles—you’ll do it in eight or nine days, even if you have to row. If you get a following wind—not unlikely at this time of year—you’ll do it in four days.” His hand stabbed at the map. “A quick march from Ravenna to Faventia, and you’ll cut Norbanus off from Ariminum permanently.”

“It will have to be done in secret,” said the Piglet, eyes shining. “Oh, yes, Pompeius, it will work! They won’t dream of our moving troops between here and Ancona—their scouts will all be to the north of the Aesis. Pompeius, Crassus, you’ll have to sit right where we are at the moment pretending to be five legions stronger until Varro Lucullus and I have sailed from Ancona. Then you move. Try to catch up to Carrinas, and make it look serious. If possible, tie him down—and Censorinus as well. Carbo will be with them at first, but when he hears I’ve landed at Ravenna, he’ll march to relieve Norbanus. Of course, he may elect to stay in this neighborhood himself, send Carrinas or Censorinus to relieve Norbanus. But I don’t think so. Carbo needs to be centrally located.”

“Oh, this is going to be tremendous fun!” cried Pompey.

And such was the contentment in the command tent that no one found this statement too flippant; even Marcus Terentius Varro, sitting quietly in a corner taking notes.

*

The strategy worked. While Metellus Pius hustled himself, Varro Lucullus and five legions to Ancona, the other six plus the cavalry pretended to be eleven. Then Pompey and Crassus moved out of the camp and crossed the Aesis without opposition; Carbo had decided, it seemed, to lure them toward Ariminum, no doubt planning a decisive battle on ground more familiar to him.

Pompey led the way with his cavalry, hard on the heels of Carbo’s rear guard, cavalry commanded by Censorinus, and nipped those heels with satisfying regularity. These tactics irritated Censorinus, never a patient man; near the town of Sena Gallica he turned and fought, cavalry against cavalry. Pompey won; he was developing a talent for commanding horse. Into Sena Gallica the smarting Censorinus retreated with infantry and cavalry both—but not for long. Pompey stormed its modest fortifications.

Censorinus then did the sensible thing. He sacrificed his horse, made off through the back gate of Sena Gallica with eight legions of infantry, and headed for the Via Flaminia.

By this time Carbo had learned of the unwelcome presence of the Piglet and his army in Faventia; Norbanus was now cut off from Ariminum. So Carbo marched for Faventia, leaving Carrinas to follow him with eight more legions; Censorinus, he decided, would have to fend for himself.

But then came Brutus Damasippus to find Carbo as he marched, and gave him the news that Sulla had annihilated the army of Young Marius at Sacriportus. Sulla was now heading up the Via Cassia toward the border of Italian Gaul at Arretium, though all the troops he had were three legions. In that instant, Carbo changed his plans. Only one thing could be done. Norbanus would have to hold Italian Gaul unaided against Metellus Pius; Carbo and his legates must halt Sulla at Arretium, not a difficult thing to do when Sulla had but three legions.

*

Pompey and Crassus got the news of Sulla’s victory over Young Marius at just about the same time as Carbo did, and hailed it with great jubilation. They turned westward to follow Carrinas and Censorinus, each now bringing eight legions to Carbo at Arretium on the Via Cassia. The pace was furious, the pursuit determined. And this, decided Pompey as he headed with Crassus for the Via Flaminia, was no campaign for cavalry; they were heading into the mountains. Back to the Aesis he sent his horse—troopers, and resumed command of his father’s veterans. Crassus, he had discovered, seemed content to follow his lead as long as what Pompey suggested added up to the right answers inside that hard round Crassus head.

Again it was the presence of so many veterans made the real difference; Pompey and Crassus caught up to Censorinus on a diverticulum of the Via Flaminia between Fulginum and Spoletium, and didn’t even need to fight a battle. Exhausted, hungry, and very afraid, the troops of Censorinus disintegrated. All Censorinus managed to retain were three of his eight legions, and these precious soldiers he determined must be saved. He marched them off the road and cut across country to Arretium and Carbo. The men of his other five legions had scattered so completely that none of them afterward were ever successfully amalgamated into new units.

Three days later Pompey and Crassus apprehended Carrinas outside the big and well-fortified town of Spoletium. This time a battle did take place, but Carrinas fared so poorly that he was forced to shut himself up inside Spoletium with three of his eight legions; three more of his legions fled to Tuder and went to earth there; and the last two disappeared, never to be found.

“Oh, wonderful!” whooped Pompey to Varro. “I see how I can say bye—bye to stolid old Crassus!”

This he did by hinting to Crassus that he should take his three legions to Tuder and besiege it, leaving Pompey to bring his own men to bear on Spoletium. Off went Crassus to Tuder, very happy at the thought of conducting his own campaign. And Pompey sat down before Spoletium in high fettle, aware that whoever sat down before Spoletium would collect most of the glory because this was where General Carrinas himself had taken refuge. Alas, things didn’t work out as Pompey had envisaged! Astute and daring, Carrinas sneaked out of Spoletium during a nocturnal thunderstorm and stole away to join Carbo with all three of his legions intact.

Pompey took Carrinas’s defection very personally; fascinated, Varro learned what a Pompeian temper tantrum looked like, complete with tears, gnawed knuckles, plucked tufts of hair, drumming of heels and fists on the floor, broken cups and plates, mangled furniture. But then, like the nocturnal thunderstorm so beneficial to Carrinas, Pompey’s thwarted rage rolled away.

“We’re off to Sulla at Clusium,” he announced. “Up with you, Varro! Don’t dawdle so!”

Shaking his head, Varro tried not to dawdle.

*

It was early in June when Pompey and his veterans marched into Sulla’s camp on the Clanis River, there to find the commander-in-chief a trifle sore and battered of spirit. Things had not gone very well for him when Carbo had come down from Arretium toward Clusium, for Carbo had nearly won the battle which developed out of a chance encounter, and therefore could not be planned. Only Sulla’s presence of mind in breaking off hostilities and retiring into a very strong camp had saved the day.

“Not that it matters,” said Sulla, looking greatly cheered. “You’re here now, Pompeius, and Crassus isn’t far away. Having both of you will make all the difference. Carbo is finished.”

“How did Metellus Pius get on?” Pompey asked, not pleased to hear Sulla mention Crassus in the same breath.

“He’s secured Italian Gaul. Brought Norbanus to battle outside Faventia, while Varro Lucullus—he’d had to go all the way to Placentia to find asylum—took on Lucius Quinctius and Publius Albinovanus near Fidentia. All went splendidly. The enemy is scattered or dead.”

“What about Norbanus himself?”

Sulla shrugged; he never cared very much what happened to his military foes once they were beaten, and Norbanus had not been a personal enemy. “I imagine he went to Ariminum,” he said, and turned away to issue instructions about Pompey’s camp.

Sure enough, Crassus arrived the following day from Tuder at the head of three rather surly and disgruntled legions; rumor was rife among their ranks that after Tuder fell, Crassus had found a fortune in gold and kept the lot.

“Is it true?” demanded Sulla, the deep folds of his face grown deeper, his mouth set so hard its lips had disappeared.

But nothing could dent that bovine composure. Crassus’s mild grey eyes widened, he looked puzzled but unconcerned. “No.”

“You’re sure?”

“There was nothing to be had in Tuder beyond a few old women, and I didn’t fancy a one.”

Sulla shot him a suspicious glance, wondering if Crassus was being intentionally insolent; but if so, he couldn’t tell. “You are as deep as you are devious, Marcus Crassus,” he said at last. “I will accord you the dispensations of your family and your standing, and elect to believe you. But take fair warning! If ever I discover that you have profited at the expense of the State out of my aims and endeavors, I will never see you again.”

“Fair enough,” said Crassus, nodding, and ambled off.

Publius Servilius Vatia had listened to this exchange, and smiled now at Sulla. “One cannot like him,” he said.

“There are few men this one does like,” said Sulla, throwing his arm around Vatia’s shoulders. “Aren’t you lucky, Vatia?”

“Why?”

“I happen to like you. You’re a good fellow—never exceed your authority and never give me an argument. Whatever I ask you to do, you do.” He yawned until his eyes watered. “I’m dry. A cup of wine, that’s what I need!”

A slender and attractive man of medium coloring, Vatia was not one of the patrician Servilii; his family, however, was more than ancient enough to pass the most rigorous of social examinations, and his mother was one of the most august Caecilii Metelli, the daughter of Metellus Macedonicus—which meant he was related to everybody who mattered. Including, by marriage, Sulla. So he felt comfortable with that heavy arm across his back, and turned within Sulla’s embrace to walk beside him to the command tent; Sulla had been imbibing freely that day, needed a little steadying.

“What will we do with these people when Rome is mine?’’ asked Sulla as Vatia helped him to a full goblet of his special wine; Vatia took his own wine from a different flagon, and made sure it was well watered.

“Which people? Crassus, you mean?”

“Yes, Crassus. And Pompeius Magnus.” Sulla’s lip curled up to show his gum. “I ask you, Vatia! Magnus! At his age!”

Vatia smiled, sat on a folding chair. “Well, if he’s too young, I’m too old. I should have been consul six years ago. Now, I suppose I never will be.”

“If I win, you’ll be consul. Never doubt it. I am a bad enemy, Vatia, but a stout friend.”

“I know, Lucius Cornelius,” said Vatia tenderly.

“What do I do with them?” Sulla asked again.

“With Pompeius, I can see your difficulty. I cannot imagine him settling back into inertia once the fighting is over, and how do you keep him from aspiring to offices ahead of his time?”

Sulla laughed. “He’s not after office! He’s after military glory. And I think I will try to give it to him. He might come in quite handy.” The empty cup was extended to be refilled. “And Crassus? What do I do with Crassus?”

“Oh, he’ll look after himself,” said Vatia, pouring. “He will make money. I can understand that. When his father and his brother Lucius died, he should have inherited more than just a rich widow. The Licinius Crassus fortune was worth three hundred talents. But of course it was confiscated. Trust Cinna! He grabbed everything. And poor Crassus didn’t have anything like Catulus’s clout.”

Sulla snorted. “Poor Crassus, indeed! He stole that gold from Tuder, I know he did.”

“Probably,” said Vatia, unruffled. “However, you can’t pursue it at the moment. You need the man! And he knows you do. This is a desperate venture.”

*

The arrival of Pompey and Crassus to swell Sulla’s army was made known to Carbo immediately. To his legates he turned a calm face, and made no mention of relocating himself or his forces. He still outnumbered Sulla heavily, which meant Sulla showed no sign of breaking out of his camp to invite another battle. And while Carbo waited for events to shape themselves, tell him what he must do, news came first from Italian Gaul that Norbanus and his legates Quinctius and Albinovanus were beaten, that Metellus Pius and Varro Lucullus held Italian Gaul for Sulla. The second lot of news from Italian Gaul was more depressing, if not as important. The Lucanian legate Publius Albinovanus had lured Norbanus and the rest of his high command to a conference in Ariminum, then murdered all save Norbanus himself before surrendering Ariminum to Metellus Pius in exchange for a pardon. Having expressed a wish to live in exile somewhere in the east, Norbanus had been allowed to board a ship. The only legate who escaped was Lucius Quinctius, who was in Varro Lucullus’s custody when the murders happened.

A tangible gloom descended upon Carbo’s camp; restless men like Censorinus began to pace and fume. But still Sulla would not offer battle. In desperation, Carbo gave Censorinus something to do; he was to take eight legions to Praeneste and relieve the siege of Young Marius. Ten days after departing, Censorinus was back. It was impossible to relieve Young Marius, he said—the fortifications Ofella had built were impregnable. Carbo sent a second expedition to Praeneste, but only succeeded in losing two thousand good men when Sulla ambushed them. A third force set off under Brutus Damasippus to find a road over the mountains and break into Praeneste along the snake—paths behind it. That too failed; Brutus Damasippus looked, abandoned all hope, and returned to Clusium and Carbo.

Even the news that the paralyzed Samnite leader Gaius Papius Mutilus had assembled forty thousand men in Aesernia and was going to send them to relieve Praeneste had no power now to lift Carbo’s spirits; his depression deepened every day. Nor did his attitude of mind improve when Mutilus sent him a letter saying his force would be seventy thousand, not forty thousand, as Lucania and Marcus Lamponius were sending him twenty thousand men, and Capua and Tiberius Gutta another ten thousand.

There was only one man Carbo really trusted, old Marcus Junius Brutus, his proquaestor. And so to Old Brutus he went as June turned into Quinctilis, and still no decision had come to him capable of easing his mind.

“If Albinovanus would stoop to murdering men he’d laughed and eaten with for months, how can I possibly be sure of any of my own legates?’’ he asked.

They were strolling down the three—mile length of the Via Principalis, one of the two main avenues within the camp, and wide enough to ensure their conversation was private.

Blinking slowly in the sunlight, the old man with the blued lips made no quick, reassuring answer; instead, he turned the question over in his mind, and when he did reply, said very soberly, “I do not think you can be sure, Gnaeus Papirius.”

Carbo’s breath hissed between his teeth; he trembled. “Ye gods, Marcus, what am I to do?”

“For the moment, nothing. But I think you must abandon this sad business before murder becomes a desirable alternative to one or more of your legates.”

“Abandon ?’’

“Yes, abandon,” said Old Brutus steadily.

“They wouldn’t let me leave!” Carbo cried, shaking now.

“Probably not. But they don’t need to know. I’ll start making our preparations, while you look as if the only thing worrying you is the fate of the Samnite army.” Old Brutus put his hand on Carbo’s arm, patted it. “Don’t despair. All will be well in the end.”

By the middle of Quinctilis, Old Brutus had finished his preparations. Very quietly in the middle of the night he and Carbo stole away without baggage or attendants save for a mule loaded down with gold ingots innocently sheathed in a layer of lead, and a large purse of denarii for traveling expenses. Looking like a tired pair of merchants, they made their way to the Etrurian coast at Telamon, and there took ship for Africa. No one molested them, no one was the slightest bit interested in the laboring mule or in what it had in its panniers. Fortune, thought Carbo as the ship slipped anchor, was favoring him!

*

Because he was paralyzed from the waist down, Gaius Papius Mutilus could not lead the Samnite/Lucanian/Capuan host himself, though he did travel with the Samnite segment of it from its training ground at Aesernia as far as Teanum Sidicinum, where the whole host occupied Sulla’s and Scipio’s old camps, and Mutilus went to stay in his own house.

His fortunes had prospered since the Italian War; now he owned villas in half a dozen places throughout Samnium and Campania, and was wealthier than he had ever been: an ironic compensation, he sometimes thought, for the loss of all power and feeling below the waist.

Aesernia and Bovianum were his two favorite towns, but his wife, Bastia, preferred to live in Teanum—she was from the district. That Mutilus had not objected to this almost constant separation was due to his injury; as a husband he was of little use, and if understandably his wife needed to avail herself of physical solace, better she did so where he was not. However, no scandalous tidbits about her behavior had percolated back to him in Aesernia, which meant either she was voluntarily as continent as his injury obliged him to be, or her discretion was exemplary. So when Mutilus arrived at his house in Teanum, he found himself quite looking forward to Bastia’s company.

“I didn’t expect to see you,” she said with perfect ease.

“There’s no reason why you should have expected me, since I didn’t write,” he said in an agreeable way. “You look well.”

“I feel well.”

“Given my limitations, I’m in pretty good health myself,” he went on, finding the reunion more awkward than he had hoped; she was distant, too courteous.

“What brings you to Teanum?” she asked.

“I’ve an army outside town. We’re going to war against Sulla. Or at least, my army is. I shall stay here with you.”

“For how long?” she enquired politely.

“Until the business is over one way or the other.”

“I see.” She leaned back in her chair, a magnificent woman of some thirty summers, and looked at him without an atom of the blazing desire he used to see in her eyes when they were first married—and he had been all a man. “How may I see to your comfort, husband? Is there any special thing you’ll need?”

“I have my body servant. He knows what to do.”

Disposing the clouds of expensive gauze about her splendid body more artistically, she continued to gaze at him out of those orbs large and dark enough to have earned her an Homeric compliment: Lady Ox-eyes. “Just you to dinner?” she asked.

“No, three others. My legates. Is that a problem?”

“Certainly not. The menu will do you honor, Gaius Papius.”

The menu did. Bastia was an excellent housekeeper. She knew two of the three men who came to eat with their stricken commander, Pontius Telesinus and Marcus Lamponius. Telesinus was a Samnite of very old family who had been a little too young to be numbered among the Samnite greats of the Italian War. Now thirty-two, he was a fine-looking man, and bold enough to eye his hostess with an appreciation only she divined. That she ignored it was good sense; Telesinus was a Samnite, and that meant he hated Romans more than he could possibly admire women.

Marcus Lamponius was the paramount chieftain from Lucania, and had been a formidable enemy to Rome during the Italian War. Now into his fifties, he was still warlike, still thirsted to let Roman blood flow. They never change, these non—Roman Italians, she thought; destroying Rome means more to them than life or prosperity or peace. More even than children.

The one among the three Bastia had never met before was a Campanian like herself, the chief citizen of Capua. His name was Tiberius Gutta, and he was fat, brutish, egotistical, as fanatically dedicated to shedding Roman blood as the others.

She absented herself from the triclinium as soon as her husband gave her permission to retire, burning with an anger she had most carefully concealed. It wasn’t fair! Things were just beginning to run so smoothly that the Italian War might not have happened, when here it was, starting all over again. She had wanted to cry out that nothing would change, that Rome would grind their faces and their fortunes into the dust yet again; but self-control had kept her tongue still. Even if they had been brought to believe her, patriotism and pride would dictate that they go ahead anyway.

The anger ate at her, refused to die away. Up and down the marble floor of her sitting room she paced, wanting to strike out at them, those stupid, pigheaded men. Especially her own husband, leader of his nation, the one to whom all other Samnites looked for guidance. And what .sort of guidance was he giving them? War against Rome. Ruination. Did he care that when he fell, everyone attached to him would also fall? Of course he did not! He was all a man, with all a man’s idiocies of nationalism and revenge. All a man, yet only half a man. And the half of him left was no use to her, no use for procreating or recreating.

She stopped, feeling the heat at the core of her all this anger had caused to boil up. Her lips were bitten, she could taste a little bead of blood. On fire. On fire.

There was a slave…. One of those Greeks from Samothrace with hair so black it shone blue in the light, brows which met across the bridge of his nose in unashamed luxuriance, and eyes the color of a mountain lake … Skin so fine it begged to be kissed … Bastia clapped her hands.

When the steward came, she looked at him with her chin up and her bitten lips as plump and red as strawberries. “Are the gentlemen in the dining room content?”

“Yes, domina.”

“Good. Continue to look after them, please. And send Hippolytus to me here. I’ve thought of something he can do for me,” she said.

The steward’s face remained expressionless; as his master Mutilus did not care to live in Teanum Sidicinum, whereas his mistress Bastia did, his mistress Bastia mattered more to him. She must be kept happy. He bowed. “I will send Hippolytus to you at once, domina,” he said, and did many obeisances as he extricated himself carefully from her room.

In the triclinium Bastia had been forgotten the moment she departed for her own quarters.

“Carbo assures me that he has Sulla tied down at Clusium,” Mutilus said to his legates.

“Do you believe that?” asked Lamponius.

Mutilus frowned. “I have no reason to think otherwise, but I can’t be absolutely sure, of course. Do you have any reason to think otherwise?”

“No, except that Carbo’s a Roman.”

“Hear, hear!” cried Pontius Telesinus.

“Fortunes change,” said Tiberius Gutta of Capua, face shining from the grease of a capon roasted with chestnut stuffing and a skin—crisping glaze of oil. “For the moment, we fight on Carbo’s side. After Sulla is defeated, we can turn on Carbo and every other Roman and rend them.”

“Absolutely,” agreed Mutilus, smiling.

“We should move on Praeneste at once,” said Lamponius.

“Tomorrow, in fact,” said Telesinus quickly.

But Mutilus shook his head emphatically. “No. We rest the men here for five more days. They’ve had a hard march, and they still have to cover the length of the Via Latina. When they get to Ofella’s siegeworks, they must be fresh.”

These things decided—and given the prospect of relative leisure for the next five days—the dinner party broke up far earlier than Mutilus’s steward had anticipated. Busy among the kitchen servants, he saw nothing, heard nothing. And was not there when the master of the house ordered his massive German attendant to carry him to the mistress’s room.

She was kneeling naked upon the pillows of her couch, legs spread wide apart, and between her glistening thighs a blue—black head of hair was buried; the compact and muscular body which belonged to the head was stretched across the couch in an abandonment so complete it looked as if it belonged to a sleeping cat. In no other place than where the head was buried did the two bodies touch; Bastia’s arms were extended behind her, their hands kneading the pillows, and his arms lolled alongside the rest of him.

The door had opened quietly; the German slave stood with his master in his hold like a bride being carried across the threshold of her new home, and waited for his next instructions with all the dumb endurance of such fellows, far from home, almost devoid of Latin or Greek, permanently transfixed with the pain of loss, unable to express that pain.

The eyes of husband and wife met. In hers there flashed a shout of triumph, of jubilation; in his an amazement without the dulling anodyne of shock. Of its own volition his gaze fell to rest upon her glorious breasts, the sleekness of her belly, and was blurred by a sudden rush of tears.

The young Greek’s utter absorption in what he was doing now caught a change, a tension in the woman having nothing to do with him; he began to lift his head. Like two striking snakes her hands locked in the blue—black hair, pressed the head down and held it there.

“Don’t stop!’’ she cried.

Unable to look away, Mutilus watched the blood—gorged tissue in her nipples begin to swell them to bursting; her hips were moving, the head riding upon them. And then, beneath her husband’s eyes, Bastia screeched and moaned the power of her massive orgasm. It seemed to Mutilus to last an eternity.

Done, she released the head and slapped the young Greek, who rolled over and lay faceup; his terror was so profound that he seemed not to breathe.

“You can’t do anything with that,” said Bastia, pointing to the slave’s diminishing erection, “but there’s nothing wrong with your tongue, Mutilus.”

“You’re right, there isn’t,” he said, every last tear dried. “It can still taste and feel. But it isn’t interested in carrion.”

The German got him out of the room, carried him to his own sleeping cubicle, and deposited him with care upon his bed. Then after he had completed his various duties he left Gaius Papius Mutilus alone. No comment, no sympathy, no acknowledgment. And that, reflected Mutilus as he turned his face into his pillow, was a greater mercy than all else. Still in his mind’s eye the image of his wife’s body burned, the breasts with their nipples popping out, and that head—that head! That head … Below his waist nothing stirred, could never stir again. But the rest of him knew torments and dreams, and longed for every aspect of love. Every aspect!

“I am not dead,” he said into the pillow, and felt the tears come. “I am not dead! But oh, by all the gods, I wish I were!”

*

At the end of June, Sulla left Clusium. With him he took his own five legions and three of Scipio’s; he left Pompey in command, a decision which hadn’t impressed his other legates at all. But, since Sulla was Sulla and no one actively argued with him, Pompey it was.

“Clean this lot up,” he said to Pompey. “They outnumber you, but they’re demoralized. However, when they discover that I’m gone for good, they’ll offer battle. Watch Damasippus, he is the most competent among them. Crassus will cope with Marcus Censorinus, and Torquatus ought to manage against Carrinas.”

“What about Carbo?’’ asked Pompey.

“Carbo is a cipher. He lets his legates do his generaling. But don’t fiddle, Pompeius! I have other work for you.”

No surprise then that Sulla took the more senior of his legates with him; neither Vatia nor the elder Dolabella could have stomached the humiliation of having to ask a twenty-three-year-old for orders. His departure came on the heels of news about the Samnites, and made Sulla’s need to reach the general area around Praeneste urgent; dispositions would have to be finished before the Samnite host drew too near.

Having scouted the whole region on that side of Rome with extreme thoroughness, Sulla knew exactly what he intended to do. The Via Praenestina and the Via Labicana were now unnegotiable thanks to Ofella’s wall and ditch, but the Via Latina and the Via Appia were still open, still connected Rome and the north with Campania and the south. If the war was to be won, it was vital that all military access between Rome and the south belong to Sulla; Etruria was exhausted, but Samnium and Lucania had scarcely been tapped of manpower or food resources.

The countryside between Rome and Campania was not easy. On the coast it deteriorated into the Pomptine Marshes, through which from Campania the Via Appia traveled a mosquito—ridden straight line until near Rome it ran up against the flank of the Alban Hills. These were not hills at all, but quite formidable mountains based upon the outpourings of an old volcano which had cut up and elevated the original alluvial Latin plain. The Alban Mount itself, center of that ancient subterranean disturbance, reared between the Via Appia and the other, more inland road, the Via Latina. South of the Alban Hills another high ridge continued to separate the Via Appia from the Via Latina, thus preventing interconnection between these two major arteries all the way from Campania to a point very near Rome. For military travel the more inland Via Latina was always preferred over the Via Appia; men got sick when they marched the Via Appia.

It was therefore preferable that Sulla station himself on the Via Latina—but at a place where he could, if necessary, transfer his forces rapidly across to the Via Appia. Both roads traversed the outer flanks of the Alban Hills, but the Via Latina did so through a defile which chopped a gap in the eastern escarpment of the ridge and allowed the road to travel onward to Rome in the flatter space between this high ground and the Alban Mount itself. At the point where the defile opened out toward the Alban Mount, a small road curved westward round this central peak, and joined the Via Appia quite close to the sacred lake of Nemi and its temple precinct.

Here in the defile Sulla sat himself down and proceeded to build immense fortified walls of tufa blocks at each end of the gorge, enclosing the side road which led to Lake Nemi and the Via Appia within his battlements. He now occupied the only place on the Via Latina at which all progress could be stopped from both directions. And, his fortifications completed within a very short time, he posted a series of watches on the Via Appia to make sure no enemy tried to outflank him by this route, from Rome as well as from Campania. All his provisions were brought along the side road from the Via Appia.

*

By the time the Samnite/Lucanian/Capuan host reached the site of Sacriportus, everyone was calling this army “the Samnites” despite its composite nature (enhanced because remnants’ of the legions scattered by Pompey and Crassus had tacked themselves on to such a strong, well-led force). At Sacriportus the host chose the Via Labicana, only to discover that Ofella had by now contained himself within a second line of fortifications, and could not be dislodged. Shining from its heights with a myriad colors, Praeneste might as well have been as far away as the Garden of the Hesperides. After riding along every inch of Ofella’s walls, Pontius Telesinus, Marcus Lamponius and Tiberius Gutta could discern no weakness, and a cross—country march by seventy thousand men with nowhere positive to go was impossible. A war council resulted in a change of strategy; the only way to draw Ofella off was to attack Rome herself. So to Rome on the Via Latina the Samnite army would go.

Back they marched to Sacriportus, and turned onto the Via Latina in the direction of Rome. Only to find Sulla sitting behind his enormous ramparts in complete control of the road. To storm his position seemed far easier than storming Ofella’s walls, so the Samnite host attacked. When they failed, they tried again. And again. Only to hear Sulla laughing at them as loudly as had Ofella.

Then came news at once cheering and depressing; those left at Clusium had sallied out and engaged Pompey. That they had gone down in utter defeat was depressing, yet seemed not to matter when compared to the message that the survivors, some twenty thousand strong, were marching south under Censorinus, Carrinas and Brutus Damasippus. Carbo himself had vanished, but the fight, swore Brutus Damasippus in his letter to Pontius Telesinus, would go on. If Sulla’s position were stormed from both sides at once at the exact same moment, he would crumble. Had to crumble!

“Rubbish, of course,” said Sulla to Pompey, whom he had summoned to his defile for a conference as soon as he had been notified of Pompey’s victory at Clusium. “They can pile Pelion on top of Ossa if they so choose, but they won’t dislodge me. This place was made for defense! Impregnable and unassailable.”

“If you’re so confident, what need can you have for me?” the young man asked, his pride at being summoned evaporating.

The campaign at Clusium had been short, grim, decisive; many of the enemy had died, many were taken prisoner, and those who got away were chiefly distinguished for the quality of the men who led their retreat; there had been no senior legates in the ranks of those who surrendered, a great disappointment. The defection of Carbo himself had not been known to Pompey until after the battle was over, when the story of his nocturnal flight was told with tears and bitterness to Pompey’s men by tribunes, centurions and soldiers alike. A great betrayal.

Hard on the heels of this had come Sulla’s summons, which Pompey had received with huge delight. His instructions were to bring six legions and two thousand horse with him; that Varro would tag along, he took for granted, whereas Crassus and Torquatus were to remain at Clusium. But what need had Sulla for more troops in a camp already bursting at the seams? Indeed, Pompey’s army had been directed into a camp on the shores of Lake Nemi and therefore adjacent to the Via Appia!

“Oh, I don’t need you here,” said Sulla, leaning his arms on the parapet of an observation tower atop his walls and peering vainly in the direction of Rome; his vision had deteriorated badly since that illness in Greece, though he disliked owning up to it. “I’m getting closer, Pompeius! Closer and closer.”

Not normally bashful, Pompey found himself unable to ask the question he burned to ask: what did Sulla intend when the war was over? How could he retain his authority, how could he possibly protect himself from future reprisals? He couldn’t keep his army with him forever, but the moment he disbanded it he would be at the mercy of anyone with the strength and the clout to call him to account. And that might be someone who at the present moment called himself a loyal follower, Sulla’s man to the death. Who knew what men like Vatia and the elder Dolabella really thought? Both of them were of consular age, even if circumstances had conspired to prevent their becoming consul. How could Sulla insulate himself? A great man’s enemies were like the Hydra—no matter how many heads he succeeded in cutting off, there were always more busily growing, and always sporting bigger and better teeth.

“If you don’t need me here, Sulla, where do you need me?” Pompey asked, bewildered.

“It is the beginning of Sextilis,” said Sulla, and turned to lead the way down the many stairs.

Nothing more was said until they emerged at the bottom into the controlled chaos beneath the walls, where men busied themselves in carrying loads of rocks, oil for burning and throwing down upon the hapless heads of those trying to scale ladders, missiles for the onagers and catapults already bristling atop the walls, stocks of spears and arrows and shields.

“It is the beginning of Sextilis?’’ Pompey prompted once they were out of the activity and had begun to stroll down the side road toward Lake Nemi.

“So it is!” said Sulla in tones of surprise, and fell about laughing at the look on Pompey’s face.

Obviously he was expected to laugh too; Pompey laughed too. “Yes, it is,” he said, and added, “the beginning of Sextilis.”

Controlling himself with an effort, Sulla decided he had had his fun. Best put the young would—be Alexander out of his misery by telling him.

“I have a special command for you, Pompeius,” he said curtly. “The rest will have to know about it—but not yet. I want you well away before the storm of protest breaks—for break, it will! You see, what I want you to do is something I ought not to ask of any man who has not been at the very least a praetor.”

Excitement growing, Pompey stopped walking, put his hand on Sulla’s arm and turned him so that his face was fully visible; bright blue eyes stared into white—blue eyes. They were now standing in a rather pretty dell to one side of the unsealed road, and the noise of so much industry to front and back was muted by great flowering banks of summer brambles, roses and blackberries.

“Then why have you chosen me, Lucius Cornelius?” Pompey asked, tones wondering. “You have many legates who fit that description—Vatia, Appius Claudius, Dolabella—even men like Mamercus and Crassus would seem more appropriate! So why me?”

“Don’t die from curiosity, Pompeius, I will tell you! But first, I must tell you exactly what it is I want you to do.”

“I am listening,” said Pompey with a great show of calm.

“I told you to bring six legions and two thousand cavalry. That’s a respectable army. You are going to take it at once to Sicily, and secure the coming harvest for me. It’s Sextilis, the harvest will begin very soon. And sitting for the most part in Puteoli harbor is the grain fleet. Hundreds upon hundreds of empty vessels. Ready—made transports, Pompeius! Tomorrow you will take the Via Appia and march for Puteoli before the grain fleet can sail. You will bear my mandate and have sufficient money to pay for the hiring of the ships, and you will have a propraetorian imperium. Post your cavalry to Ostia, there’s a smaller fleet there. I’ve already sent out messengers to ports like Tarracina and Antium, and told all the little shipowners to gather in Puteoli if they want to be paid for what would under normal circumstances be an empty voyage out. You’ll have more than enough ships, I guarantee you.”

Had he once dreamed of a meeting between himself and an equally godlike man called Lucius Cornelius Sulla? And been crushed to abject misery because he had found a satyr, not a god? But what did the look of a man matter, when he held in both hands such a store of dreams? The scarred and drunken old man whose eyes were not even good enough to see Rome in the distance was offering him the whole conduct of a war! A war far away from interference, against an enemy he would have all to himself… Pompey gasped, held out his freckled hand with its short and slightly crooked fingers, and clasped Sulla’s beautiful hand.

“Lucius Cornelius, that’s wonderful! Wonderful! Oh, you can count on me! I’ll drive Perperna Veiento out of Sicily and give you more wheat than ten armies could eat!”

“I’m going to need more wheat than ten armies could eat,” said Sulla, releasing his hand; despite his youth and undeniable attractions, Pompey was not a type who appealed to Sulla physically, and he never liked to touch men or women who didn’t appeal to him physically. “By the end of this year, Rome will be mine. And if I want Rome to lie down for me, then I’ll have to make sure she’s not hungry. That means the Sicilian grain harvest, the Sardinian grain harvest—and, if possible, the African grain harvest too. So when you’ve secured Sicily, you’ll have to move on to Africa Province and do what you can there. You won’t be in time to catch the loaded fleets from Utica and Hadrumetum—I imagine you’ll be many months in Sicily before you can hope to deal with Africa. But Africa must be subdued before you can come home to Italy. I hear that Fabius Hadrianus was burned to death in the governor’s palace during an uprising in Utica, but that Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus—having escaped from Sacriportus!—has taken over and is holding Africa for the enemy. If you’re in western Sicily, it’s a short distance from Lilybaeum to Utica by sea. You ought to be able to wrap up Africa. Somehow you don’t have the look of a failure about you.”

Pompey was literally shivering in excitement; he smiled, gasped. “I won’t fail you, Lucius Cornelius! I promise I will never fail you!”

“I believe you, Pompeius.” Sulla sat down on a log, licked his lips. “What are we doing here? I need wine!”

“Here is a good place, there’s no one to see us or listen to us,” said Pompey soothingly. “Wait, Lucius Cornelius. I’ll fetch you wine. Just sit there and wait.”

As it was a shady spot, Sulla did as he was told, smiling at some secret joke. Oh, what a lovely day it was!

Back came Pompey at a run, yet breathing as if he hadn’t run at all. Sulla grabbed at the wineskin, squirted liquid into his mouth with great expertise, actually managing to swallow and take in air at the same time. Some moments elapsed before he ceased to squeeze, put the skin down.

“Oh, that’s better! Where was I?”

“You may fool some people, Lucius Cornelius, but not me. You know precisely where you were,” said Pompey coolly, and sat himself on the grass directly in front of Sulla’s log.

“Very good! Pompeius, you’re as rare as an ocean pearl the size of a pigeon’s egg! And I can truly say that I am very glad I’ll be dead long before you become a Roman headache.” He picked up the wineskin again, drank again.

“I’ll never be a Roman headache,” said Pompey innocently. “I will just be the First Man in Rome—and not by mouthing a lot of pretentious rubbish in the Forum or the Senate, either.”

“How then, boy, if not through stirring speeches?”

“By doing what you’re sending me off to do. By beating Rome’s enemies in battle.”

“Not a novel approach,” said Sulla. “That’s the way I’ve done it. That’s the way Gaius Marius did it too.”

“Yes, but I’m not going to need to snatch my commissions,” said Pompey. “Rome is going to give me every last one on her very knees!”

Sulla might have interpreted that statement as a reproach, or even as an outright criticism; but he knew his Pompey by this, and understood that most of what the young man said arose out of egotism, that Pompey as yet had no idea how difficult it might be to make that statement come true. So all Sulla did was to sigh and say, “Strictly speaking, I can’t give you any sort of imperium. I’m not consul, and I don’t have the Senate or the People behind me to pass my laws. You’ll just have to accept that I will make it possible for you to come back and be confirmed with a praetor’s imperium.”

“I don’t doubt that.”

“Do you doubt anything?”

“Not if it concerns me directly. I can influence events.”

“May you never change!” Sulla leaned forward, clasped his hands between his knees. “All right, Pompeius, the compliments are over. Listen to me very carefully. There are two more things I have to tell you. The first concerns Carbo.”

“I’m listening,” said Pompey.

“He sailed from Telamon with Old Brutus. Now it’s possible that he headed for Spain, or even for Massilia. But at this time of year, his destination was more likely Sicily or Africa. While ever he’s at large, he is the consul. The elected consul. That means he can override the imperium of a governor, commandeer the governor’s soldiers or militia, call up auxiliaries, and generally make a thorough nuisance of himself until his term as consul runs out. Which is some months off. I am not going to tell you exactly what I plan to do after Rome is mine, but I will tell you this—it is vital to my plans that Carbo be dead well before the end of his year in office. And it is vital that I know Carbo is dead! Your job is to track Carbo down and kill him. Very quietly and inconspicuously—I would like his death to seem an accident. Will you undertake to do this?”

“Yes,” said Pompey without hesitation.

“Good! Good!” Sulla turned his hands over and inspected them as if they belonged to someone else. “Now I come to my last point, which concerns the reason why I am entrusting this overseas campaign to you rather than to one of my senior legates.” He peered at the young man intently. “Can you see why for yourself, Pompeius?’’

Pompey thought, shrugged. “I have some ideas, perhaps, but without knowing what you plan to do after Rome is yours, I am mostly likely wrong. Tell me why.”

“Pompeius, you are the only one I can entrust with this commission! If I give six legions and two thousand horse to a man as senior as Vatia or Dolabella and send that man off to Sicily and Africa, what’s to stop his coming back with the intention of supplanting me? All he has to do is to remain away long enough for me to be obliged to disband my own army, then return and supplant me. Sicily and Africa are not campaigns likely to be finished in six months, so it’s very likely that I will have had to disband my own army before whoever I send comes home. I cannot keep a permanent standing army in Italy. There’s neither the money nor the room for it. And the Senate and People of Rome would never consent. Therefore I must keep every man senior enough to be my rival under my eye. Therefore it is you I am sending off to secure the harvest and make it possible for me to feed ungrateful Rome.”

Pompey drew a breath, linked his arms around his knees and looked at Sulla very directly. “And what’s to stop me doing all of that, Lucius Cornelius? If I’m capable of running a campaign, am I not capable of thinking I can supplant you?”

A question which plainly didn’t send a single shiver down Sulla’s spine; he laughed heartily. “Oh, you can think it all you like, Pompeius! But Rome would never wear you! Not for a single moment. She’d wear Vatia or Dolabella. They have the years, the relations, the ancestors, the clout, the clients. But a twenty-three-year-old from Picenum that Rome doesn’t know? Not a chance!”

And so they left the matter, walked off in opposite directions. When Pompey encountered Varro he said very little, just told that indefatigable observer of life and nature that he was to go to Sicily to secure the harvest. Of imperium, older men, the death of Carbo and much else, he said nothing at all. Of Sulla he asked only one favor—that he might be allowed to take his brother-in-law, Gaius Memmius, as his chief legate. Memmius, several years older than Pompey but not yet a quaestor, had been serving in the legions of Sulla.

“You’re absolutely right, Pompeius,” said Sulla with a smile. “An excellent choice! Keep your venture in the family.”

*

The simultaneous attack on Sulla’s fortifications from north and south came to pass two days after Pompey had departed with his army for Puteoli and the grain fleet. A wave of men broke on either wall, but the waves ebbed and died away harmlessly. Sulla still owned the Via Latina, and those attacking from the north could find no way to join up with those attacking on the south. At dawn on the second morning after the attack, the watchers in the towers on either wall could see no enemy; they had packed up and stolen off in the night. Reports came in all through that day that the twenty thousand men belonging to Censorinus, Carrinas and Brutus Damasippus were marching down the Via Appia toward Campania, and that the Samnite host was marching down the Via Latina in the same direction.

“Let them go,” said Sulla indifferently. “Eventually I suppose they’ll come back—united. And when they do come back it will be on the Via Appia. Where I will be waiting for them.”

By the end of Sextilis, the Samnites and the remnants of Carbo’s army had joined forces at Fregellae, and there moved off the Via Latina eastward through the Melfa Gorge.

“They’re going to Aesernia to think again,” said Sulla, and did not instruct that they be followed further. “It’s enough to post lookouts on the Via Latina at Ferentinum, and the Via Appia at Tres Tabernae. I don’t need more warning than that, and I’m not going to waste my scouts sending them to sneak around Samnites in Samnite territory like Aesernia.”

*

The action shifted abruptly to Praeneste, where Young Marius, restless and growing steadily more unpopular within the town, emerged from the gates and ventured out into No Man’s Land. At the westernmost point of the ridge, where the watershed divided Tolerus streams from Anio streams, he began to build a massive siege tower, having judged that at this point Ofella’s wall was weakest. No tree had been left standing to furnish materials for this work anywhere within reach of those defending Praeneste; it was houses and temples yielded up the timber, precious nails and bolts, blocks and panels and tiles.

The most dangerous work was to make a smooth roadway for the tower to be moved upon between the spot where it was being built and the edge of Ofella’s ditch, for these laborers were at the mercy of marksmen atop Ofella’s walls; Young Marius chose the youngest and swiftest among his helpers to do this, and gave them a makeshift roof under which to shelter. Out of harm’s reach another team toiled with pieces of timber too small to use in constructing the tower, and made a bridge of laminated planking to throw across the ditch when it came time to push the tower right up against Ofella’s wall. Once work upon the tower had progressed enough to create a shelter inside it for those who labored upon building it, the thing seemed to grow from within, up and up and up, out and out and out.

In a month it was ready, and so were the causeway and the bridge along which a thousand pairs of hands would propel it. But Ofella too was ready, having had plenty of time to prepare his defenses. The bridge was put across the ditch in the darkest hours of night, the tower rolled heaving and groaning upon a slipway of sheep’s fat mixed with oil; dawn saw the tower, twenty feet higher than the top of Ofella’s wall, in position. Deep in its bowels there hung upon ropes toughened with pitch a mighty battering ram made from the single beam which had spanned the Goddess’s cella in the temple of Fortuna Primigenia, who was the firstborn daughter of Jupiter, and talisman of Italian luck.

But it was many a year before tufa stone hardened to real brittleness, so the ram when brought to bear on Ofella’s wall roared and boomed and pounded in vain; the elastic tufa blocks shook, even trembled and vibrated, but they held until Ofella’s catapults firing blazing missiles had set the tower on fire, and driven the attackers hurling spears and arrows fleeing with hair in flames. By nightfall the tower was a twisted ruin collapsed in the ditch, and those who had tried to break out were either dead or back within Praeneste.

Several times during October, Young Marius tried to use the bridged ditch filled with the wreckage of his tower as a base; he roofed a section between Ofella’s wall and the ditch to keep his men safe and tried to mine his way beneath the wall, then tried to cut his way through the wall, and finally tried to scale the wall. But nothing worked. Winter was close at hand, seemed to promise the same kind of bitter cold as the last one; Praeneste knew itself short of food, and rued the day it had opened its gates to the son of Gaius Marius.

*

The Samnite host had not gone to Aesernia at all. Ninety thousand strong, it sat itself down in the awesome mountains to the south of the Fucine Lake and whiled away almost two months in drills, foraging parties, more drills. Pontius Telesinus and Brutus Damasippus had journeyed to see Mutilus in Teanum, come away armed with a plan to take Rome by surprise—and without Sulla’s knowledge. For, said Mutilus, Young Marius would have to be left to his fate. The only chance left for all right—thinking men was to capture Rome and draw both Sulla and Ofella into a siege which would be prolonged and filled with a terrible doubt—would those inside Rome elect to join the Samnite cause?

There was a way across the mountains between the Melfa Gorge and the Via Valeria. This stock route—for so it was better termed than road—traversed the ranges between Atina at the back of the Melfa Gorge—a wilderness—went to Sora on the elbow of the Liris River, then to Treba, then to Sublaquaeum, and finally emerged on the Via Valeria a scant mile east of Varia, at a little hamlet called Mandela. It was neither paved nor even surveyed, but it had been there for centuries, and was the route whereby the many shepherds of the mountains moved their flocks each summer season between pastures at the same altitude. It was also the route the flocks took to the sale yards and slaughterhouses of the Campus Lanatarius and the Vallis Camenarum adjoining the Aventine parts of Rome.

Had Sulla stopped to remember the time when he had marched from Fregellae to the Fucine Lake to assist Gaius Marius to defeat Silo and the Marsi, he might have remembered this stock route, for he had actually followed a part of it from Sora to Treba, and had not found it impossible going. But at Treba he had left it, and had not thought to ascertain whereabouts it went north of Treba. So the one chance Sulla might have had to circumvent Mutilus’s strategy was overlooked. Thinking that the only route open to the Samnites if they planned to attack Rome was the Via Appia, Sulla remained in his defile on the Via Latina and kept watch, sure he could not be taken by surprise.

And while he sat in his defile, the Samnites and their allies toiled along the stock route, secure in the knowledge that they were passing through country whose inhabitants had no love of Rome, and well beyond the outermost tentacles of Sulla’s intelligence network. Sora, Treba, Sublaquaeum, and finally onto the Via Valeria at Mandela. They were now a scant day’s march from Rome, a mere thirty miles of superbly kept road as the Via Valeria came down through Tibur and the Anio valley, and terminated on the Campus Esquilinus beneath the double rampart of Rome’s Agger.

But this was not the best place from which to launch an attack on Rome, so when the great host drew close to the city, Pontius Telesinus and Brutus Damasippus took a diverticulum which brought them out on the Via Nomentana at the Colline Gate. And there outside the Colline Gate—waiting for them,as it were—was the stout camp Pompey Strabo had built for himself during Cinna’s and Gaius Marius’s siege of Rome. By nightfall of the last day of October, Pontius Telesinus, Brutus Damasippus, Marcus Lamponius, Tiberius Gutta, Censorinus and Carrinas were comfortably ensconced within that camp; on the morrow they would attack.

*

The news that ninety thousand men were occupying Pompey Strabo’s old camp outside the Colline Gate was brought to Sulla after night had fallen on the last day of October. It found him a little the worse for wine, but not yet asleep. Within moments bugles were blaring, drums were rolling, men were tumbling from their pallets and torches were kindling everywhere. Icily sober, Sulla called his legates together and told them.

“They’ve stolen a march on us,” he said, lips compressed. “How they got there I don’t know, but the Samnites are outside the Colline Gate and ready to attack Rome. By dawn, we march. We have twenty miles to cover and some of it’s hilly, but we have to get to the Colline Gate in time to fight tomorrow.” He turned to his cavalry commander, Octavius Balbus. “How many horses have you got around Lake Nemi, Balbus?”

“Seven hundred,” said Balbus.

“Then off you go right now. Take the Via Appia, and ride like the wind. You’ll reach the Colline Gate some hours before I can hope to get the infantry there, so you’ve got to hold them off. I don’t care what you have to do, or how you do it! Just get there and keep them occupied until I arrive.”

Octavius Balbus wasted no time speaking; he was out of Sulla’s door and roaring for a horse before Sulla could turn back to his other legates.

There were four of them—Crassus, Vatia, Dolabella and Torquatus. Shocked, but not bereft of their wits.

“We have eight legions here, and they will have to do,” said Sulla. “That means we’ll be outnumbered two to one. I’ll make my dispositions now because there may not be the time for conferences after we reach the Colline Gate.”

He fell silent, studying them. Who would fare best? Who would have the steel to lead in what was going to be a desperate encounter? By rights it ought to be Vatia and Dolabella, but were they the best men? His eyes dwelt upon Marcus Licinius Crassus, huge and rock—solid, never anything save calm—eaten up with avarice, a thief and a swindler—not principled, not ethical, perhaps moral. And yet of the four of them he had the most to lose if this war was lost. Vatia and Dolabella would survive, they had the clout. Torquatus was a good man, but not a true leader.

Sulla made up his mind. “I will move in two divisions of four legions each,” he said, slapping his hands on his thighs. “I will retain the high command myself, but I will not command either division. For want of a better way to distinguish them, I’ll call them the left and the right, and unless I change my orders after we arrive, that is how they’ll fight. Left and right of the field. No center. I haven’t enough men. Vatia, you will command the left, with Dolabella as your second-in-command. Crassus, you’ll command the right, with Torquatus as your second-in-command.”

As he spoke, Sulla’s eyes rested upon Dolabella, saw the anger and outrage; no need to look at Marcus Crassus, he would not betray his feelings.

“That is what I want,” he said harshly, spitting out the words because they shaped themselves poorly without teeth. “I don’t have time for argument. You’ve all thrown in your lots with me, you’ve given me the ultimate decisions. Now you’ll do as you’re told. All I expect of you is the will to fight in the way I command you to fight.”

Dolabella stood back at the door and allowed the other three to precede him; then he turned back. “A word with you alone, Lucius Cornelius,” he said.

“If it’s quick.”

A Cornelius and a remote relation of Sulla’s, Dolabella was not from a branch of that great family which had managed to acquire the luster of the Scipiones—or even of the Sullae; if he had anything in common with most of the Cornelii, it was his homeliness—plump cheeks, a frowning face, eyes a little too close together. Ambitious and with a reputation for depravity, he and his first cousin, the younger Dolabella, were determined to win greater prominence for their branch of the family.

“I could break you, Sulla,” Dolabella said. “All I have to do is make it impossible for you to win tomorrow’s fight. And I imagine you understand that I’ll change sides so fast the opposition will end in believing I was always with them.”

“Do go on!” said Sulla in the most friendly fashion when Dolabella paused to see how this speech had been received.

“However, I am willing to lie down under your decision to promote Marcus Crassus over my head. On one condition.”

“Which is?”

“That next year, I am consul.”

“Done!” cried Sulla with the greatest goodwill.

Dolabella blinked. “You’re not put out?” he asked.

“Nothing puts me out anymore, my dear Dolabella,” said Sulla, escorting his legate to the door. “At the moment it makes little odds to me who is consul next year. What matters at the moment is who commands on the field tomorrow. And I see that I was right to prefer Marcus Crassus. Good night!”

*

The seven hundred horsemen under the command of Octavius Balbus arrived outside Pompey Strabo’s camp about the middle of the morning on the first day of November. There was absolutely nothing Balbus could have done had he been put to it; his horses were so blown that they stood with heads hanging, sides heaving and white with sweat, mouths dripping foam, while their riders stood alongside them and tried to comfort them by loosening girths and speaking soft endearments. For this reason Balbus had not halted too close to the enemy—let them think his force was ready for action! So he arranged it in what appeared to be a charge formation, had his troopers brandish their lances and pretend to shout messages back to an unseen army of infantry in their rear.

It was evident that the attack upon Rome had not yet begun. The Colline Gate stood in majestic isolation, its portcullis down and its two mighty oak doors closed; the battlements of the two towers which flanked it were alive with heads, and the walls which ran away on either side were heavily manned. Balbus’s arrival had provoked sudden activity within the enemy camp, where soldiers were pouring out of the southeastern gate and lining up to hold off a cavalry onslaught; of enemy cavalry there was no sign, and Balbus could only hope that none was concealed.

Each trooper on the march carried a leather bucket tied to his left rear saddle horn to water his horse; while the front rank carried on with the farce of a coming charge and an invisible army of foot soldiers behind, other troopers ran with the buckets to various fountains in the vicinity and filled them. As soon as the horses could safely be watered, Octavius Balbus intended that the business should be finished in short order.

So successful was this mock show of aggression that nothing further had happened when Sulla and his infantry arrived some four hours later, in the early afternoon. His men were in much the same condition as Balbus’s horses had been; exhausted, blown, legs trembling with the effort of marching at the double across twenty miles of sometimes steep terrain.

“Well, we can’t possibly attack today,” said Vatia after he and Sulla had ridden with the other legates to inspect the ground and see what sort of battle was going to develop.

“Why not?” asked Sulla.

Vatia looked blank. “They’re too tired to fight!”

“Tired they may be, but fight they will,” said Sulla.

“You can’t, Lucius Cornelius! You’d lose!”