Having been freed from his flaminate and ordered to do military duty under the governor of Asia Province, Marcus Minucius Thermus, Gaius Julius Caesar left for the east a month short of his nineteenth birthday, accompanied by two new servants and his German freedman, Gaius Julius Burgundus. Though most men heading for Asia Province sailed, Caesar had decided to go by land, a distance of eight hundred miles along the Via Egnatia from Apollonia in western Macedonia to Callipolis on the Hellespont. As it was summer by the calendar and the seasons, the journey was not uncomfortable, though devoid for the most part of the inns and posting houses so prevalent throughout Italy; those who went overland to Asia camped.

Because flamen Dialis was not allowed to travel, Caesar had been obliged to travel in his mind, which had devoured every book set in foreign parts, and imagined what the world might look like. Not, he soon learned, as it really was; but the reality was so much more satisfying than imagination! As for the act of travel—even Caesar, so eloquent, could not find the words to describe it. For in him was a born traveler, adventurous, curious, insatiably eager to sample everything. As he went he talked to the whole world, from shepherds to salesmen, from mercenaries looking for work to local chieftains. His Greek was Attic and superlative, but all those odd tongues he had picked up from infancy because his mother’s insula contained a polyglot mixture of tenants now stood him in good stead; not because he was lucky enough to find people who spoke them as he went along, but because his intelligence was attuned to strange words and accents, so he was able to hear the Greek in some strange patois, and discern foreign words in basic Greek. It made him a good traveler, in that he was never lost for means of communication.

It would have been wonderful to have had Bucephalus to ride, of course, but young and trusty Flop Ears the mule was not a contemptuous steed in any way save appearance; there were times when Caesar fancied it owned claws rather than hooves, so surefooted was it on rough terrain. Burgundus rode his Nesaean giant, and the two servants rode very good horses—if he himself was on his honor not to bestride any mount except Flop Ears, then the world would have to accept this as an eccentricity, and understand from the caliber of his servants’ horses that he was not financially unable to mount himself well. How shrewd Sulla was! For that was where it hurt—Caesar liked to make a good appearance, to dazzle everyone he encountered. A little difficult on a mule!

The first part of the Via Egnatia was the wildest and most inhospitable, for the road, unpaved but well surveyed, climbed the highlands of Candavia, tall mountains which probably hadn’t changed much since well before the time of Alexander the Great. A few flocks of sheep, and once in the distance a sight of mounted warriors who might have been Scordisci, were all the evidence of human occupation the travelers saw. From Macedonian Edessa, where the fertile river valleys and plains offered a better livelihood, men became more numerous and settlements both larger and closer together. In Thessalonica, Caesar sought and was given accommodation in the governor’s palace, a welcome chance to bathe in hot water—ablutions since leaving Apollonia had been in river or lake, and very cold, even in summer. Though invited to stay longer, Caesar remained only one day there before journeying on.

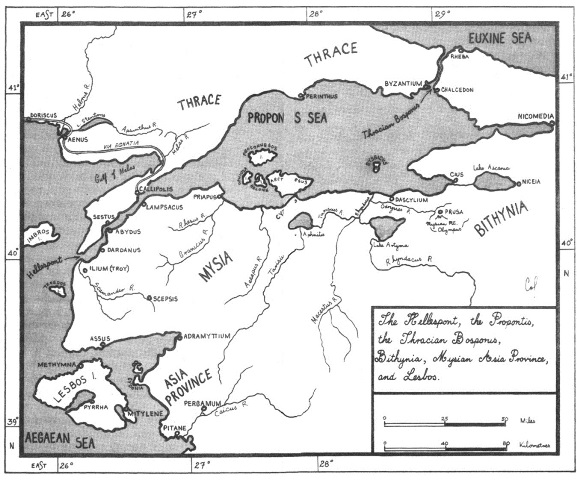

Philippi—the scene of several battles of fame and recently occupied by one of the sons of King Mithridates—he found interesting because of its history and its strategic position on the flanks of Mount Pangaeus; though even more interesting was the road to the east of it, where he could see the military possibilities inherent in the narrow passes before the countryside flattened a little and the terrain became easier again. And finally there lay before him the Gulf of Melas, mountain—ringed but fertile; a crust of ridge beyond it and the Hellespont came into view, more than merely a narrow strait. It was the place where Helle tumbled from the back of the Golden Ram and gave her name to the waters, it was the site of the Clashing Rocks which almost sank the Argo, it was the place where armies of Asiatic kings from Xerxes to Mithridates had poured in their thousands upon thousands from Asia into Thrace. The Hellespont was the true crossroads between East and West.

In Callipolis, Caesar took ship at last for the final leg of his journey, aboard a vessel which had room to accommodate the horses, the mule and the pack animals, and which was sailing direct to Pergamum. He was hearing now of the revolt of Mitylene and the siege which was under way, but his orders were to report in Pergamum; he could only hope he would be posted to a war zone.

But the governor, Marcus Minucius Thermus, had other duties in mind for Caesar. “It’s vital that we contain this rebellion,” he said to this new junior military tribune, “because it’s caused by the new system of taxation the Dictator has put into Asia Province. Island states like Lesbos and Chios were very well off under Mithridates, and they’d love to see the end of Rome. Some cities on the mainland feel much the same. If Mitylene succeeds in holding out for a year, we’ll have other places thinking they can revolt too. One of the difficulties in containing Mitylene is its double harbor, and the fact that we don’t have a proper fleet. So you, Gaius Julius, are going to see King Nicomedes in Bithynia and levy a fleet from him. When you’ve gathered it, I want you to sail it to Lesbos and put it at the disposal of my legate, Lucullus, who is in charge of the investment.”

“You’ll have to forgive my ignorance, Marcus Minucius,” said Caesar, “but how long does it take to gather a fleet, and how many vessels of what kind do you want?’’

“It takes forever,” said Thermus wearily, “and you’ll get whatever the King can scrape together—or it might be more accurate to say that you’ll get as little as the King can escape with. Nicomedes is no different from any other oriental potentate.”

The nineteen-year-old frowned, not pleased at this answer, and proceeded to demonstrate to Thermus that he owned a great deal of natural—though not unattractive—arrogance. “That’s not good enough,” he said. “What Rome wants, Rome must have.”

Thermus couldn’t help himself; he laughed. “Oh, you have a lot to learn, young Caesar!” he said.

That didn’t sit well. Caesar compressed his lips and looked very like his mother (whom Thermus didn’t know, or he might have understood Caesar better). “Well, Marcus Minucius, why don’t you tell me your ideal delivery date and your ideal fleet composition?” he asked haughtily. “Then I will take it upon myself to deliver your ideal fleet on your ideal date.”

Thermus’s jaw dropped, and for a moment he genuinely didn’t know how best to answer. That this superb self-confidence did not provoke a fit of anger in him, he himself found interesting; nor this time did the young man’s arrogance provoke laughter. The governor of Asia Province actually found himself believing that Caesar truly thought himself capable of doing what he said. Time and King Nicomedes would rectify the mistake, but that Caesar could make it was indeed interesting, in view of the letter from Sulla which Caesar had presented to him.

He has some claim on me through marriage, this making him my nephew, but I wish to make it abundantly clear that I do not want him favored. In fact, do not favor him! I want him given difficult things to do, and difficult offices to occupy. He owns a formidable intelligence coupled with high courage, and it’s possible he’ll do extremely well.

However, if I exclude Caesar’s conduct during the course of two interviews with me, his history to date has been uninspiring, thanks to his being the flamen Dialis. From this he is now released, legally and religiously. But it means that he has not done military service, so his valor may simply be verbal.

Test him, Marcus Minucius, and tell my dear Lucullus to do the same. If he breaks, you have my full permission to be as ruthless as you like in punishing him. If he does not break, I expect you to give him his due.

I have a last, if peculiar, request. If at any time you witness or learn that Caesar has ridden a better animal than his mule, send him home at once in disgrace.

In view of this letter, Thermus, recovering from his utter stupefaction, said in even tones, “All right, Gaius Julius, I’ll give you a time and a size. Deliver the fleet to Lucullus’s camp on the Anatolian shore to the north of the city on the Kalends of November. You won’t stand a chance of prising one vessel but of old Nicomedes by then, but you asked for a delivery date, and the Kalends of November would be ideal—we’d be able to cut off both harbors before the winter—and give them a hard one. As to size: forty ships, at least half of which should be decked triremes or larger. Again, you’ll be lucky if you get thirty ships, and of those, about five decked triremes.”

Thermus looked stern. “However, young Caesar, since you opened your mouth, I feel it my duty to warn you that if you are late or if the fleet is less than ideal, it will go against you in my report to Rome.”

“As it should,” said Caesar, undismayed.

“You may have rooms here in the palace for the time being,” said Thermus cordially; despite Sulla’s giving him permission, it was no part of Thermus’s policy to antagonize someone related to the Dictator.

“No, I’m off to Bithynia today,” said Caesar, moving toward the door.

“There’s no need to overdo it, Gaius Julius!”

“Perhaps not. But there’s every need to get going,” said Caesar, and got going.

It was some time before Thermus went back to his endless paperwork. What an extraordinary fellow! Very well mannered, but in that inimitable way only patricians of the great families seemed to own; the young man left it in no doubt that he liked all men and felt himself superior to none, while at the same time knowing himself superior to all save (perhaps) a Fabius Maximus. Impossible to define, but that was the way they were, especially the Julians and the Fabians. So good-looking! Having no sexual liking for men, Thermus pondered about Caesar in that respect; looks of Caesar’s kind very often predisposed their possessors toward a sexual liking for men. Yet, he decided, Caesar had not behaved preciously at all.

The paperwork reproached silently and Thermus went back to it; within moments he had forgotten all about Gaius Julius Caesar and the impossible fleet.

*

Caesar went overland from Pergamum without permitting his tiny entourage a night’s rest in a Pergamum inn. He followed the course of the Caicus River to its sources before crossing a high ridge and coming down to the valley of the Macestus River, known as the Rhyndacus closer to the sea; the latter, it seemed from talking to various locals, he would do better not to aim for. Instead he turned off the Rhyndacus parallel to the coast of the Propontis and went to Prusa. There was, he had been told, just a chance that King Nicomedes was visiting his second—largest city. Prusa’s position on the flanks of an imposing snow—covered massif appealed to Caesar strongly, but the King was not in residence. On went Caesar to the Sangarius River, and, after a short ride to the west of it, came to the principal royal seat of Nicomedia dreaming upon its long, sheltered inlet.

So different from Italy! Bithynia, he had discovered, was soft in climate rather than hot, and amazingly fertile thanks to its series of rivers, all flowing more strongly at this time of year than Italian rivers. Clearly the King ruled a prosperous realm, and his people wanted for nothing. Prusa had contained no poverty—stricken inhabitants; nor, it turned out, did Nicomedia.

The palace stood upon a knoll above the town, yet within the formidable walls. Caesar’s initial impression was of Greek purity of line, Greek colors, Greek design—and considerable wealth, even if Mithridates had ruled here for several years while the Bithynian king had retreated to Rome. He never remembered seeing the King in Rome, but that was not surprising; Rome allowed no ruling king to cross the pomerium, so Nicomedes had rented a prohibitively expensive villa on the Pincian Hill and done all his negotiating with the Senate from that location.

At the door of the palace Caesar was greeted by a marvelously effeminate man of unguessable age who eyed him up and down with an almost slavering appreciation, sent another effeminate fellow off with Caesar’s servants to stable the horses and the mule, and conducted Caesar to an anteroom where he was to wait until the King had been informed and his accommodation decided upon. Whether Caesar would succeed in obtaining an immediate audience with the King, the steward (for so he turned out to be) could not say.

The little chamber where Caesar waited was cool and very beautiful, its walls unfrescoed but divided into a series of panels formed by plaster moldings, the cornices gilded to match the panel borders and pilasters. Inside the panels the color was a soft shell—pink, outside them a deep purplish—red.

The floor was a marble confection in purples and pinks, and the windows—which looked onto what seemed to be the palace gardens—were shuttered from the outside, thus loomed as framed landscapes of exquisite terraces, fountains, blooming shrubs. So lush were the flowers that their perfumes seeped into the room; Caesar stood inhaling, his eyes closed.

What opened them was the sound of raised voices coming from beyond a half—opened door set into one wall: a male voice, high and lisping, and a female voice, deep and booming.

“Jump!” said the woman. “Upsy—daisy!”

“Rubbish!” said the man. “You degrade it!”

“Oozly—woozly—soozly!” said the woman, and produced a huge whinny of laughter.

“Go away!” from the man.

“Diddums!” from the woman, laughing again.

Perhaps it was bad manners, but Caesar didn’t care; he moved to a spot from which his eyes could see what his ears were already hearing. The scene in the adjacent chamber—obviously some sort of private sitting room—was fascinating. It involved a very old man, a big woman perhaps ten years younger, and an elderly, roly—poly dog of some smallish breed Caesar didn’t recognize. The dog was performing tricks—standing on its hind legs to beg, lying down and squirming over, playing dead with all four feet in the air. Throughout its repertoire it kept its eyes fixed upon the woman, evidently its owner.

The old man was furious. “Go away, go away, go away!” he shouted. As he wore the white ribbon of the diadem around his head, the watcher in the other room deduced he was King Nicomedes.

The woman (the Queen, as she also wore a diadem) bent over to pick up the dog, which scrambled hastily to its feet to avoid being caught, ran round behind her, and bit her on her broad plump bottom. Whereupon the King fell about laughing, the dog played dead again, and the Queen stood rubbing her buttock, clearly torn between anger and amusement. Amusement won, but not before the dog received her well-aimed foot neatly between its anus and its testicles. It yelped and fled, the Queen in hot pursuit.

Alone (apparently he didn’t know the next—door room was occupied, nor had anyone yet told him of Caesar’s advent), the King’s laughter died slowly away. He sat down in a chair and heaved a sigh, it would seem of satisfaction.

Just as Marius and Julia had experienced something of a shock when they had set eyes upon this king’s father, so too did Caesar absorb King Nicomedes the Third with considerable amazement. Tall and thin and willowy, he wore a floor—length robe of Tyrian purple embroidered with gold and sewn with pearls, and flimsy pearl—studded golden sandals which revealed that he gilded his toenails. Though he wore his own hair—cut fairly short and whitish—grey in color—he had caked his face with an elaborate maquillage of snow—white cream and powder, carefully drawn in soot—black brows and lashes, artificially pinkened his cheeks, and heavily carmined his puckered old mouth.

“I take it,” said Caesar, strolling into the room, “that Her Majesty got what she deserved.”

The King of Bithynia goggled. There before him stood a young Roman, clad for the road in plain leather cuirass and kilt. He was very tall and wide—shouldered, but the rest of him looked more slender, except that the calves of his legs were well developed above finely turned ankles wrapped around with military boots. Crowned by a mop of pale gold hair, the Roman’s head was a contradiction in terms, as its cranium was so large and round that it looked bulbous, whereas its face was long and pointed. What a face! All bones—but such splendid bones, stretched over with smooth pale skin, and illuminated by a pair of large, widely spaced eyes set deep in their sockets. The fair brows were thinnish, the fair lashes thick and long; the eyes themselves could be, the King suspected, disquieting, for their light blue irises were ringed with a blue so dark it appeared black, and gave the black pupils a piercing quality softened at the moment by amusement. To the individual taste of the King, however, all else was little compared to the young man’s mouth, full yet disciplined, and with the most kissable, dented corners.

“Well, hello!” said the King, sitting upright in a hurry, his pose one of bridling seductiveness.

“Oh, stop that!” said Caesar, inserting himself into a chair opposite the King’s.

“You’re too beautiful not to like men,” the King said, then looked wistful. “If only I were even ten years younger!”

“How old are you?” asked Caesar, smiling to reveal white and regular teeth.

“Too old to give you what I’d like to!”

“Be specific—about your age, that is.”

“I am eighty.”

“They say a man is never too old.”

“To look, no. To do, yes.”

“Think yourself lucky you can’t rise to the occasion,” said Caesar, still smiling easily. “If you could, I’d have to wallop you—and that would create a diplomatic incident.”

“Rubbish!” scoffed the King. “You’re far too beautiful to be a man for women.”

“In Bithynia, perhaps. In Rome, certainly not.”

“Aren’t you even tempted?”

“No.”

“What a disgraceful waste!”

“I know a lot of women who don’t think so.”

“I’ll bet you’ve never loved one of them.”

“I love my wife,” said Caesar.

The King looked crushed. “I will never understand Romans!” he exclaimed. “You call the rest of the world barbarian, but it is you who are not civilized.”

Draping one leg over the arm of his chair, Caesar swung its foot rhythmically. “I know my Homer and Hesiod,” he said.

“So does a bird, if you teach it.”

“I am not a bird, King Nicomedes.”

“I rather wish you were! I’d keep you in a golden cage just to look at you.”

“Another household pet? I might bite you.”

“Do!” said the King, and bared his scrawny neck.

“No, thanks.”

“This is getting us nowhere!” said the King pettishly.

“Then you have absorbed the lesson.”

“Who are you?”

“My name is Gaius Julius Caesar, and I’m a junior military tribune attached to the staff of Marcus Minucius Thermus, governor of Asia Province.”

“Are you here in an official capacity?”

“Of course.”

“Why didn’t Thermus notify me?”

“Because I travel faster than heralds and couriers do, though why your own steward hasn’t announced me I don’t know,” said Caesar, still swinging his foot.

At that moment the steward entered the room, and stood aghast to see the visitor sitting with the King.

“Thought you’d get in first, eh?” asked the King. “Well, Sarpedon, abandon all hope! He doesn’t like men.” His head turned back to Caesar, eyes curious. “Julius. Patrician?”

“Yes.”

“Are you a relative of the consul who was killed by Gaius Marius? Lucius Julius Caesar?”

“He and my father were first cousins.”

“Then you’re the flamen Dialis!”

“I was the flamen Dialis. You’ve spent time in Rome.”

“Too much of it.” Suddenly aware the steward was still in the room, the King frowned. “Have you arranged accommodation for our distinguished guest, Sarpedon?”

“Yes, sire.”

“Then wait outside.”

Bowing severally, the steward eased himself out backward.

“What are you here for?’’ asked the King of Caesar.

The leg was returned to the floor; Caesar sat up squarely. “I’m here to obtain a fleet.”

No particular expression came into the King’s eyes. “Hmm! A fleet, eh? How many ships are you after, and what kind?”

“You forgot to ask when by,” said this awkward visitor.

“Add, when by.”

“I want forty ships, half of which must be decked triremes or larger, all collected in the port of your choice by the middle of October,” said Caesar.

“Two and a half months away? Oh, why not just cut off both my legs?” yelled Nicomedes, leaping to his feet.

“If I don’t get what I want, I will.”

The King sat down again, an arrested look in his eyes. “I remind you, Gaius Julius, that this is my kingdom, not a province of Rome,” he said, his ridiculously carmined mouth unable to wear such anger appropriately. “I will give you whatever I can whenever I can! You ask! You don’t demand.”

“My dear King Nicomedes,” said Caesar in a friendly way, “you are a mouse caught in the middle of a path used by two elephants—Rome and Pontus.” His eyes had ceased to smile, and Nicomedes was suddenly hideously reminded of Sulla. “Your father died at an age too advanced to permit you tenure of this throne before you too were an old man. The years since your accession have surely shown you how tenuous your position is—you’ve spent as many of them in exile as you have in this palace, and you are only here now because Rome in the person of Gaius Scribonius Curio put you back. If Rome, which is a great deal further away from Pontus than you are, is well aware that King Mithridates is far from finished—and far from being an old man!—then you too must know it. The land of Bithynia has been called Friend and Ally of the Roman People since the days of the second Prusias, and you yourself have tied yourself inextricably to Rome. Evidently you’re more comfortable ruling than in exile. That means you must co-operate with Rome and Rome’s requests. Otherwise, Mithridates of Pontus will come galumphing down the path toward Rome galumphing the opposite way—and you, poor little mouse, will be squashed flat by one set of feet—or the other.”

The King sat without a thing to say, crimson lips agape, eyes wide. After a long and apparently breathless pause, he took air into his chest with a gasp, and his eyes filled with tears. “That isn’t fair!” he said, and broke down completely.

Exasperated beyond endurance, Caesar got to his feet, one hand groping inside the armhole of his cuirass for a handkerchief; he walked across to the King and thrust the piece of cloth at him. “For the sake of the position you hold, compose yourself! Though it may have commenced informally, this is an audience between the King of Bithynia and Rome’s designated representative. Yet here you sit bedizened like a saltatrix tonsa, and snivel when you hear the unvarnished truth! I was not brought up to chastise venerable grandfathers who also happen to be Rome’s client kings, but you invite it! Go and wash your face, King Nicomedes, then we’ll begin again.”

Docile as a child, the King of Bithynia got up and left.

In a very short time he was back, face scrubbed clean, and accompanied by several servants bearing trays of refreshments.

“The wine of Chios,” said the King, sitting down and beaming at Caesar without, it seemed, resentment. “Twenty years old!”

“I thank you, but I’d rather have water.”

“Water?”

The smile was back in Caesar’s eyes. “I am afraid so. I have no liking for wine.”

“Then it’s as well that the water of Bithynia is renowned,” said the King. “What will you eat?”

Caesar shrugged indifferently. “It doesn’t matter.”

King Nicomedes now bent a different kind of gaze upon his guest; searching, unaffected by his delight in male beauty. So he looked beyond what had previously fascinated him in Caesar, down into the layers below. “How old are you, Gaius Julius?”

“I would prefer that you call me Caesar.”

“Until you begin to lose your wonderful head of hair,” said the King, betraying the fact that he had been in Rome long enough to learn at least some Latin.

Caesar laughed. “I agree it is difficult to bear a cognomen meaning a fine head of hair! I’ll just have to hope that I follow the Caesars in keeping it into old age, rather than the Aurelians in losing it.” He paused, then said, “I’m just nineteen.”

“Younger than my wine!” said the King in a voice of wonder. “You have Aurelius in you too? Orestes or Cotta?”

“My mother is an Aurelia of the Cottae.”

“And do you look like her? I don’t see much resemblance in you to Lucius Caesar or Caesar Strabo.”

“I have some characteristics from her, some from my father. If you want to find the Caesar in me, think not of Lucius Caesar’s younger brother, but his older one—Catulus Caesar. All three of them died when Gaius Marius came back, if you remember.”

“Yes.” Nicomedes sipped his Chian wine pensively, then said, “I usually find Romans are impressed by royalty. They seem in love with the philosophy of being Republican, but susceptible to the reality of kingship. You, however, are not a bit impressed.”

“If Rome had a king, sire, I’d be it,” said Caesar simply.

“Because you’re a patrician?”

“Patrician?” Caesar looked incredulous. “Ye gods, no! I am a Julian! That means I go back to Aeneas, whose father was a mortal man, but whose mother was Venus—Aphrodite.”

“You are descended from Aeneas’s son, Ascanius?”

“We call Ascanius by the name Iulus,” said Caesar.

“The son of Aeneas and Creusa?”

“Some say so. Creusa died in the flames of Troy, but her son did escape with Aeneas and Anchises, and did come to Latium. But Aeneas also had a son by Lavinia, the daughter of King Latinus. And he too was called Ascanius, and Iulus.”

“So which son of Aeneas are you descended from?”

“Both,” said Caesar seriously. “I believe, you see, that there was only one son—the puzzle lies in who mothered him, as everyone knows his father was Aeneas. It is more romantic to believe that Iulus was the son of Creusa, but more likely, I think, that he was the son of Lavinia. After Aeneas died and Iulus grew up, he founded the city of Alba Longa on the Alban Mount—uphill from Bovillae, you might say. Iulus died there, and left his family behind to continue to rule—the Julii. We were the Kings of Alba Longa, and after it fell to King Servius Tullius of Rome, we were brought into Rome as her foremost citizens. We are still Rome’s foremost citizens, as is demonstrated by the fact that we are the hereditary priests of Jupiter Latiaris, who is older by far than Jupiter Optimus Maximus.”

“I thought the consuls celebrated those rites,” said King Nicomedes, revealing more knowledge of things Roman.

“Only at his annual festival, as a concession to Rome.”

“Then if the Julii are so august, why haven’t they been more prominent during the centuries of the Republic?’’

“Money,” said Caesar.

“Oh, money!” exclaimed the King, looking enlightened. “A terrible problem, Caesar! For me too. I just haven’t the money to give you your fleet—Bithynia is broke.”

“Bithynia is not broke, and you will give me my fleet, O king of mice! Otherwise—splosh! You’ll be spread as thin as a wafer under an elephant’s foot.”

“I haven’t got it to give you!”

“Then what are we doing sitting wasting time?” Caesar stood. “Put down your cup, King Nicomedes, and start up the machinery!” A hand went under the King’s elbow. “Come on, up with you! We will go down to the harbor and see what we can find.”

Outraged, Nicomedes shook himself free. “I wish you would stop telling me what to do!”

“Not until you do it!”

“I’ll do it, I’ll do it!”.

“Now. There’s no time like the present.”

“Tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow might see King Mithridates appear over the hill.”

“Tomorrow will not see King Mithridates! He’s in Colchis, and two thirds of his soldiers are dead.”

Caesar sat down, looking interested. “Tell me more.”

“He took a quarter of a million men to teach the savages of the Caucasus a lesson for raiding Colchis. Typical Mithridates! Couldn’t see how he could lose fielding so many men. But the savages didn’t even need to fight. The cold in the high mountains did the work for them. Two thirds of the Pontic soldiers died of exposure,” said Nicomedes.

“Rome doesn’t know this.” Caesar frowned. “Why didn’t you inform the consuls?”

“Because it’s only just happened—and anyway, it is not my business to tell Rome!”

“While you’re Friend and Ally, it most definitely is. The last we heard of Mithridates, he was up in Cimmeria reshaping his lands at the north of the Euxine.”

“He did that as soon as Sulla ordered Murena to leave Pontus alone,” nodded Nicomedes. “But Colchis had been refractory with its tribute, so he stopped off to rectify that and found out about the barbarian incursions.”

“Very interesting.”

“So as you can see, there is no elephant.”

Caesar’s eyes twinkled. “Oh yes there is! An even larger elephant. It’s called Rome.”

The King of Bithynia couldn’t help it; he doubled up with laughter. “I give in, I give in! You’ll have your fleet!”

Queen Oradaltis walked in, the dog at her heels, to find her ancient husband without his face painted, and crying with laughter. Also decently separated by some feet from a young Roman who looked just the sort of fellow who would be sitting in much closer proximity to one like King Nicomedes.

“My dear, this is Gaius Julius Caesar,” said the King when he sobered a little. “A descendant of the goddess Aphrodite, and far better born than we are. He has just maneuvered me into giving him a large and prestigious fleet.”

The Queen (who had no illusions whatsoever about Nicomedes) inclined her head regally. “I’m surprised you haven’t just given him the whole kingdom,” she said, pouring herself a goblet of wine and taking up a cake before she sat down.

The dog bumbled over to Caesar and dumped itself on his feet, gazing up adoringly. When Caesar bent to give it a resounding pat, it collapsed, rolled over, and presented its fat belly to be scratched.

“What’s his name?” asked Caesar, who clearly liked dogs.

“Sulla,” said the Queen.

A vision of her sandaled toe administering a kick to Sulla’s private parts rose up before Caesar’s inner gaze; it was now his turn to double up with laughter.

Over dinner he learned of the fate of Nysa, only child of the King and Queen, and heir to the Bithynian throne.

“She’s fifty and childless,” said Oradaltis sadly. “We refused to allow Mithridates to marry her, naturally, but that meant he made it impossible for us to find a suitable husband for her elsewhere. It is a tragedy.”

“May I hope to meet her before I leave?” asked Caesar.

“That is beyond our power,” sighed Nicomedes. “When I fled to Rome the last time Mithridates invaded Bithynia, I left Nysa and Oradaltis here in Nicomedia. So Mithridates carried our girl off as a hostage. He still has her in his custody.”

“And did he marry her?”

“We think not. She was never a beauty, and she was even then too old to have children. If she defied him openly he may have killed her, but the last we heard she was alive and being held in Cabeira, where he keeps women like the daughters and sisters he won’t permit to marry,” said the Queen.

“Then we’ll hope that when next the two elephants collide on that path, King Nicomedes, the Roman elephant wins the encounter. If I’m not personally a part of the war, I’ll make sure whoever is in command knows whereabouts Princess Nysa is.”

“By then I hope I’ll be dead,” said the King, meaning it.

“You can’t die before you get your daughter back!”

“If she should ever come back it will be as a Pontic puppet, and that is the reality,” said Nicomedes bitterly.

“Then you had better leave Bithynia to Rome in your will.”

“As the third Attalus did with Asia, and Ptolemy Apion with Cyrenaica? Never!” declared the King of Bithynia.

“Then it will fall to Pontus. And Pontus will fall to Rome, which means Bithynia will end up Roman anyway.”

“Not if I can help it.”

“You can’t help it,” said Caesar gravely.

*

The next day the King escorted Caesar down to the harbor, where he was assiduous in pointing out the complete absence of ships rigged for fighting.

“You wouldn’t keep a navy here,” said Caesar, not falling for it. “I suggest we ride for Chalcedon.”

“Tomorrow,” said the King, more enchanted with his difficult guest in every passing moment.

“We’ll start today,” said Caesar firmly. “It’s—what? Forty miles from here? We won’t do it in one ride.”

“We’ll go by ship,” said the King, who loathed traveling.

“No, we’ll go overland. I like to get the feel of terrain. Gaius Marius—who was my uncle by marriage—told me I should always journey by land if possible. Then if in future I should campaign there, I would know the lie of the land. Very useful.”

“So both Marius and Sulla are your uncles by marriage.”

“I’m extraordinarily well connected,” said Caesar solemnly.

“I think you have everything, Caesar! Powerful relatives, high birth, a fine mind, a fine body, and beauty. I am very glad I am not you.”

“Why?”

“You’ll never not have enemies. Jealousy—or envy, if you prefer to use that term to describe the coveting of characteristics rather than love—will dog your footsteps as the Furies did poor Orestes. Some will envy you the beauty, some the body or its height, some the birth, some the mind. Most will envy you all of them. And the higher you rise, the worse it will become. You will have enemies everywhere, and no friends. You will be able to trust neither man nor woman.”

Caesar listened to this with a sober face. “Yes, I think that is a fair comment,” he said deliberately. “What do you suggest I do about it?”

“There was a Roman once in the time of the Kings. His name was Brutus,” said the King, displaying yet more knowledge of Rome. “Brutus was very clever. But he hid it under a facade of brutish stupidity, hence his cognomen. So when King Tarquinius Superbus killed men in every direction, it never once occurred to him to kill Brutus. Who deposed him and became the first consul of the new Republic.”

“And executed his own sons when they tried to bring King Tarquinius Superbus back from exile and restore the monarchy to Rome,” said Caesar. “Pah! I’ve never admired Brutus. Nor will I emulate him by pretending I’m stupid.”

“Then you must take whatever comes.”

“Believe me, I intend to take whatever comes!”

“It’s too late to start for Chalcedon today,” said the King slyly. “I feel like an early dinner, then we can have some more of this wonderfully stimulating conversation, and ride at dawn.”

“Oh, we’ll ride at dawn,” said Caesar cheerfully, “but not from here. I’m leaving for Chalcedon in an hour. If you want to come, you’ll have to hurry.”

Nicomedes hurried, for two reasons: the first was that he knew he had to keep a strict eye on Caesar, who was highhanded; and the second that he was fathoms deep in love with the young man who continued to profess that he had no weakness for men.

He found Caesar being thrown up into the saddle of a mule.

“A mule?”

“A mule,” said Caesar, looking haughty.

“Why?”

“It’s an idiosyncrasy.”

“You’re on a mule, and your freedman rides a Nesaean?”

“So your eyes obviously tell you.”

Sighing, the King was helped tenderly into his two—wheeled carriage, which followed Caesar and Burgundus at a steady walk. However, when they paused for the night under the roof of a baron so old he had never expected to see his sovereign again, Caesar apologized to Nicomedes.

“I’m sorry. My mother would say I didn’t stop to think. You’re very tired. We ought to have sailed.”

“My body is devastated, that’s true,” said Nicomedes with a smile. “However, your company makes me young again.”

Certainly when he joined Caesar to break his fast on the morning after they had arrived in Chalcedon (where there was a royal residence), he was bright and talkative, seemed well rested.

“As you can see,” he said, standing on the massive mole which enclosed Chalcedon’s harbor, “I have a neat little navy. Twelve triremes, seven quinqueremes, and fourteen undecked ships. Here, that is. I have more in Chrysopolis and in Dascylium.”

“Doesn’t Byzantium take a share of the Bosporan tolls?”

“Not these days. The Byzantines used to levy the tolls—they were very powerful, used to have a navy almost the equal of the Rhodians. But after the fall of Greece and then Macedonia, they had to keep a large land army to repel the Thracian barbarians, who still raid them. Simply, Byzantium couldn’t afford to keep a navy as well as an army. So the tolls passed to Bithynia.”

“Which is why you have several neat little navies.”

“And why I have to retain my neat little navies! I can donate Rome ten triremes and five quinqueremes altogether, from what is here and what is elsewhere. And ten undecked ships. The rest of your fleet I’ll hire.”

“Hire?” asked Caesar blankly.

“Of course. How do you think we raise navies?”

“As we do! By building ships.”

“Wasteful—but then you Romans are that,” said the King. “Keeping your own ships afloat when you don’t need them costs money. So we Greek—speaking peoples of Asia and the Aegean keep our fleets down to a minimum. If we need more in a hurry, we hire them. And that is what I’ll do.”

“Hire ships from where?” asked Caesar, bewildered. “If there were ships to be had along the Aegean, I imagine Thermus would have commandeered them already.”

“Of course not from the Aegean!” said Nicomedes scornfully, delighted that he was teaching something to this formidably knowledgeable youth. “I’ll hire them from Paphlagonia and Pontus.”

“You mean King Mithridates would hire ships to his enemy?”

“Why would he not? They’re lying idle at the moment, and costing him money. He doesn’t have all those soldiers to fill them, and I don’t think he plans an invasion of Bithynia or the Roman Asian province this year—or next year!”

“So we will blockade Mitylene with ships belonging to the kingdom Mitylene so badly wants to ally itself with,” said Caesar, shaking his head. “Extraordinary!”

“Normal,” said Nicomedes briskly.

“How do you go about the business of hiring?”

“I’ll use an agent. The most reliable fellow is right here in Chalcedon.”

It occurred to Caesar that perhaps if ships were being hired by the King of Bithynia for Rome’s use, it ought to be Rome paying the bill, but as Nicomedes seemed to regard the present situation as routine, Caesar wisely held his tongue; for one thing, he had no money, and for another, he wasn’t authorized to find the money. Best then to accept things as they were. But he began to see why Rome had problems in her provinces, and with her client kings. From his conversation with Thermus, he had assumed Bithynia would be paid for this fleet at some time in the future. Now he wondered exactly how long Bithynia would have to wait.

“Well, that’s all fixed up,” said the King six days later. “Your fleet will be waiting in Abydus harbor for you to pick it up on the fifteenth day of your October. That is almost two months away, and of course you will spend them with me.”

“It is my duty to see to the assembling of the ships,” said Caesar, not because he wished to avoid the King, but because he believed it ought to be so.

“You can’t,” said Nicomedes.

“Why?”

“It isn’t done that way.”

Back to Nicomedia they went, Caesar nothing loath; the more he had to do with the old man, the more he liked him. And his wife. And her dog.

*

Since there were two months to while away, Caesar planned to journey to Pessinus, Byzantium, and Troy. Unfortunately the King insisted upon accompanying him to Byzantium, and upon a sea journey, so Caesar never did get to either Pessinus or Troy; what ought to have been a matter of two or three days in a ship turned into almost a month. The royal progress was tediously slow and formal as the King called into every tiny fishing village and allowed its inhabitants to see him in all his glory—though, in deference to Caesar, without his maquillage.

Always Greek in nature and population, Byzantium had existed for six hundred years upon the tip of a hilly peninsula on the Thracian side of the Bosporus, and had a harbor on the horn—shaped northern reach as well as one on the southern, more open side. Its walls were heavily fortified and very high, its wealth manifest in the size and beauty of its buildings, private as well as public.

The Thracian Bosporus was more beautiful than the Hellespont—and more majestic, thought Caesar, having sailed through the Hellespont. That King Nicomedes was the city’s suzerain became obvious from the moment the royal barge was docked; every man of importance came flocking to greet him. However, it did not escape Caesar that he himself got a few dark looks, or that there were some present who did not like to see the King of Bithynia on such good terms with a Roman. Which led to another dilemma. Until now Caesar’s public associations with King Nicomedes had all been inside Bithynia, where the people knew their ruler so well that they loved his whole person, and understood him. It was not like that in Byzantium, where it soon became obvious that everyone assumed Caesar was the King of Bithynia’s boyfriend.

It would have been easy to refute the assumption—a few words here and there about silly old fools who made silly old fools of themselves, and what a nuisance it was to be obliged to dicker for a fleet with a silly old fool. The trouble was, Caesar couldn’t bring himself to do that; he had grown to love Nicomedes in every way except the one way Byzantium assumed he did, and he couldn’t hurt the poor old man in that one place he himself was hurting most—his pride. But there were cogent reasons why he ought to make the true situation clear, first and foremost because his own future was involved. He knew where he was going—all the way to the top. Bad enough to attempt that hard climb hiding a part of his nature which was real; but worse by far to attempt it knowing that the inference was quite unjustified. If the King had been younger he might have decided upon a direct appeal, for though Nicomedes condemned the Roman intolerance of homosexuality as un—Hellenic, barbarian even, he would out of his naturally warm and affectionate nature have striven to dispel the illusion. But at his advanced age, Caesar couldn’t be sure that the hurt this request would produce would not also be too severe. In short, life, Caesar was discovering after that enclosed and sheltered adolescence he had been forced to endure, could hand a man conundrums to which there were no adequate answers.

Byzantine resentment of Romans was due, of course, to the occupation of the city by Fimbria and Flaccus four years earlier, when they—appointed by the government of Cinna—had decided to head for Asia and a war with Mithridates rather than for Greece and a war with Sulla. It made little difference to the Byzantines that Fimbria had murdered Flaccus, and Sulla had put paid to Fimbria; the fact remained that their city had suffered. And here was their suzerain fawning all over another Roman.

Thus, having arrived at what decisions he could, Caesar set out to make his own individual impression on the Byzantines, intending to salvage what pride he could. His intelligence and education were a great help, but he was not so sure about that element of his nature that his mother so deplored—his charm. It did win over the leading citizens of the city and it did much to mollify their feelings after the singular boorishness and brutishness of Flaccus and Fimbria, but he was forced in the end to conclude that it probably strengthened their impressions of his sexual leanings—male men weren’t supposed to be charming.

So Caesar embarked upon a frontal attack. The first phase of this consisted in crudely rebuffing all the overtures made to him by men, and the second phase in finding out the name of Byzantium’s most famous courtesan, then making love to her until she cried enough.

“He’s as big as a donkey and as randy as a goat,” she said to all her friends and regular lovers, looking exhausted. Then she smiled and sighed, and stretched her arms voluptuously. “Oh, but he’s wonderful! I haven’t had a boy like him in years!”

And that did the trick. Without hurting King Nicomedes, whose devotion to the Roman youth was now seen for what it was. A hopeless passion.

Back to Nicomedia, to Queen Oradaltis, to Sulla the dog, to that crazy palace with its surplus of pages and its squabbling, intriguing staff.

“I’m sorry to have to go,” he said to the King and Queen at their last dinner together.

“Not as sorry as we are to see you go,” said Queen Oradaltis gruffly, and stirred the dog with her foot.

“Will you come back after Mitylene is subdued?’’ asked the King. “We would so much like that.”

“I’ll be back. You have my word on it,” said Caesar.

“Good!” Nicomedes looked satisfied. “Now, please enlighten me about a Latin puzzle I have never found the answer to: why is cunnus masculine gender, and mentula feminine gender?’’

Caesar blinked. “I don’t know!”

“There must surely be a reason.”

“Quite honestly, I’ve never thought about it. But now that you’ve drawn it to my attention, it is peculiar, isn’t it?”

“Cunnus should be cunna—it’s the female genitalia, after all. And mentula should be mentulus—it’s a man’s penis, after all. Below so much masculine bluster, how hopelessly confused you Romans are! Your women are men, and your men, women.” And the King sat back, beaming.

“You didn’t choose the politest words for our private parts,” said Caesar gravely. “Cunnus and mentula are obscenities.” He kept his face straight as he went on. “The answer is obvious, I would have thought. The gender of the equipment indicates the sex it is intended to mate with—the penis is meant to find a female home, and a vagina is meant to welcome a male home.”

“Rubbish!” said the King, lips quivering.

“Sophistry!” said the Queen, shoulders shaking.

“What do you have to say about it, Sulla?” asked Nicomedes of the dog, with which he was getting on much better since the advent of Caesar—or perhaps it was that Oradaltis didn’t use the dog to tease the old man so remorselessly these days.

Caesar burst out laughing. “When I get home, I will most certainly ask him!”

*

The palace was utterly empty after Caesar left; its two aged denizens crept around bewildered, and even the dog mourned.

“He is the son we never had,” said Nicomedes. “No!” said Oradaltis strongly. “He is the son we could never have had. Never.”

“Because of my family’s predisposition?”

“Of course not! Because we aren’t Romans. He is Roman.”

“Perhaps it would be better to say, he is himself.”

“Do you think he will come back, Nicomedes?’’ A question which seemed to cheer the King up. He said very firmly, “Yes, I believe he will.”

*

When Caesar arrived in Abydus on the Ides of October, he found the promised fleet riding at anchor—two massive Pontic sixteeners, eight quinqueremes, ten triremes, and twenty well-built but not particularly warlike galleys.

“Since you wish to blockade rather than pursue at sea,” said part of the King’s letter to Caesar, “I have given you as your minor vessels broad—beamed, decked, converted merchantmen rather than the twenty undecked war galleys you asked for. If you wish to keep the men of Mitylene from having access to their harbor during the winter, you will need sturdier vessels than lightweight galleys, which have to be drawn up on shore the moment a storm threatens. The converted merchantmen will ride out all but gales so terrible no one will be on the sea. The two Pontic sixteeners I thought might come in handy, if for no other reason than they look so fearsome and daunting. They will break any harbor chain known, so will be useful when you attack. Also, the harbor master at Sinope was willing to throw them in for nothing beyond food and wages for their crews (five hundred men apiece), as he says the King of Pontus can find absolutely no work for them to do at the moment. I enclose the bill on a separate sheet.”

The distance from Abydus on the Hellespont to the Anatolian shore of the island of Lesbos just to the north of Mitylene was about a hundred miles, which, said the chief pilot when Caesar applied to him for the information, would take between five and ten days if the weather held and every ship was genuinely seaworthy.

“Then we’d better make sure they all are,” said Caesar.

Not used to working for an admiral (for such, Caesar supposed, was his status until he reached Lesbos) who insisted that his ships be gone over thoroughly before the expedition started, the chief pilot assembled Abydus’s three shipwrights and inspected each vessel closely, with Caesar hanging over their shoulders badgering them with ceaseless questions.

“Do you get seasick?’’ asked the chief pilot hopefully.

“Not as far as I know,” said Caesar, eyes twinkling.

Ten days before the Kalends of November the fleet of forty ships sailed out into the Hellespont, where the current—which always flowed from the Euxine into the Aegean—bore them at a steady rate toward the southern mouth of the strait at the Mastusia promontory on the Thracian side, and the estuary of the Scamander River on the Asian side. Not far down the Scamander lay Troy—fabled Ilium, from the burning ruins of which his ancestor Aeneas had fled before Agamemnon could capture him. A pity that he hadn’t had a chance to visit this awesome site, Caesar thought, then shrugged; there would be other chances.

*

The weather held, with the result that the fleet—still keeping well together—arrived off the northern tip of Lesbos six days early. Since it was no part of Caesar’s plan to get to his destination on any other day than the Kalends of November, he consulted the chief pilot again and put the fleet snugly into harbor within the curling palm of the Cydonian peninsula, where it could not be seen from Lesbos. The enemy on Lesbosdid not concern him: he wanted to surprise the besieging Roman army. And cock a snook at Thermus.

“You have phenomenal luck,” said the chief pilot when the fleet put out again the day before the Kalends of November.

“In what way?”

“I’ve never seen better sailing conditions for this time of the year—and they’ll hold for several days yet.”

“Then at nightfall we’ll put in to whatever sheltering bay we can find on Lesbos. At dawn tomorrow I’ll take a fast lighter to find the army,” said Caesar. “There’s no point in bringing the whole fleet down until I find out whereabouts the commander wants to base it.”

*

Caesar found his army shortly after the sun had risen on the following day, and went ashore to find Thermus or Lucullus, whoever was in command. Lucullus, as it turned out. Thermus was still in Pergamum.

They met below the spot where Lucullus was supervising the construction of a wall and ditch across the narrow, hilly spit of land on which stood the city of Mitylene.

It was Caesar of course who was curious; Lucullus was just testy, told no more than that a strange tribune wanted to see him, and deeming all unknown junior officers pure nuisances. His reputation in Rome had grown over the years since he had been Sulla’s faithful quaestor, the only legate who had agreed to the march on Rome that first time, when Sulla had been consul. And he had remained Sulla’s man ever since, so much so that Sulla had entrusted him with commissions not usually given to men who had not been praetor; he had waged war against King Mithridates and he had stayed in Asia Province after Sulla went home, holding it for Sulla while the governor, Murena, had busied himself conducting an unauthorized war against Mithridates in the land of Cappadocia.

Caesar saw a slim, fit-looking man of slightly more than average height, a man who walked a little stiffly—not, it seemed, because there was anything wrong with his bones, but rather because the stiffness was in his mind. Not a handsome man—but definitely an interesting-looking one—he had a long, pale face surmounted by a thatch of wiry, waving hair of that indeterminate color called mouse—brown. When he came close enough to see his eyes, Caesar discovered they were a clear, light, frigid grey.

The commander’s brows were knitted into a frown. “Yes?”

“I am Gaius Julius Caesar, junior military tribune.”

“Sent from the governor, I presume?”

“Yes.”

“So? Why did you have to ask for. me? I’m busy.”

“I have your fleet, Lucius Licinius.”

“My fleet?”

“The one the governor told me to obtain from Bithynia.”

The cold regard became fixed. “Ye gods!”

Caesar stood waiting.

“Well, that is good news! I didn’t realize Thermus had sent two tribunes to Bithynia,” said Lucullus. “When did he send you? In April?”

“As far as I know, I’m the only one he sent.”

“Caesar—Caesar … You can’t be the one he sent at the end of Quinctilis, surely!”

“Yes, I am.”

“And you have a fleet already?”

“Yes.”

“Then you’ll have to go back, tribune. King Nicomedes has palmed you off with rubbish.”

“This fleet contains no rubbish. I have forty ships I have personally inspected for seaworthiness—two sixteeners, eight quinqueremes, ten triremes, and twenty converted merchantmen the King said would be better for a winter blockade than light undecked war galleys,” said Caesar, hugging his delight inside himself so secretly not a scrap of it showed.

“Ye gods!” Lucullus now inspected this junior military tribune as minutely as he would a freak in a sideshow at the circus. A faint turn began to work at tugging the left corner of his mouth upward, and the eyes melted a little. “How did you manage that?”

“I’m a persuasive talker.”

“I’d like to know what you said! Nicomedes is as tight as a miser’s clutch on his last sestertius.”

“Don’t worry, Lucius Licinius, I have his bill.”

“Call me Lucullus, there are at least six Lucius Liciniuses here.” The general turned to walk toward the seashore. “I’ll bet you have the bill! What is he charging us for sixteeners?”

“Only the food and wages of their crews.”

“Ye gods! Where is this magical fleet?”

“About a mile upshore toward the Hellespont, riding at anchor. I thought it would be better to come ahead myself and ask you whether you want it moored here, or whether you’d rather it went straight on to blockade the Mitylene harbors.”

Some of the stiffness had gone from Lucullus’s gait. “I think we’ll put it straight to work, tribune.” He rubbed his hands together. “What a shock for Mitylene! Its men thought they’d have all winter to bring in extra provisions.”

When the two men reached the lighter and Lucullus stepped nimbly on board, Caesar hung back.

“Well, tribune? Aren’t you coming?”

“If you wish. I’m a little new to military etiquette, so I don’t want to make any mistakes,” said Caesar frankly.

“Get in, man, get in!”

It was not until the twenty oarsmen, ten to a side, had turned the open boat into the north and commenced the long, easy strokes which ate up distance that Lucullus spoke again.

“New to military etiquette? You’re well past seventeen, tribune, are you not? You didn’t say you were a contubernalis.’’

Stifling a sigh (he could see that he would be tired of explaining long before explanations were no longer necessary), Caesar said in matter—of—fact tones, “I am nineteen, but this is my first campaign. Until June I was the flamen Dialis.’’

But Lucullus never wanted lavish details; he was too busy and too intelligent. So he nodded, taking for granted all the things most men wanted elaborated. “Caesar … Was your aunt Sulla’s first wife?”

“Yes.”

“So he favors you.”

“At the moment.”

“Well answered! I am his loyalest follower, tribune, and I say that as a warning I owe to you, considering your relationship to him. I do not permit anyone to criticize him.”

“You’ll hear no criticisms from me, Lucullus.”

“Good.”

A silence fell, broken only by the uniform grunt of twenty oarsmen dipping simultaneously into the water. Then Lucullus spoke again, with some amusement.

“I would still like to know how you prised such a mighty fleet out of King Nicomedes.”

And that secret delight suddenly popped to the surface in a manner Caesar had not yet learned to discipline; he said something indiscreet to someone he didn’t know. “Suffice it to say that the governor annoyed me. He refused to believe that I could produce forty ships, half of them decked, by the Kalends of November. I was injured in my pride, and undertook to produce them. And I have produced them! The governor’s lack of faith in my ability to live up to my word demanded it.”

This answer irritated Lucullus intensely; he loathed having cocksure men in his army at any level, and he found the statement detestably arrogant. He therefore set out to put this cocksure child in his place. “I know that painted old trollop Nicomedes extremely well,” he said in a freezing voice. “Of course you are very pretty, and he is very notorious. Did he fancy you?’’ But, as he had no intention of permitting Caesar to reply, he went on immediately. “Yes, of course he fancied you! Oh, well done for you, Caesar! It isn’t every Roman who has the nobility of purpose to put Rome ahead of his chastity. I think we’ll have to call you the face that launched forty ships. Or should that be arse?”

The anger flared up in Caesar so quickly that he had to drive his nails into his palms to keep his arms by his sides; in all his life he had never had to fight so hard to keep his head. But keep it he did. At a price he was never to forget. His eyes turned to Lucullus, wide and staring. And Lucullus, who had seen eyes like that many times before, lost his color. Had there been anywhere to go he would have stepped back out of reach; instead he held his ground. But not without an effort.

“I had my first woman,” said Caesar in a flat voice, “at about the time I had my fourteenth birthday. I cannot count the number I have had since. This means I know women very well. And what you have just accused me of, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, is the kind of trickery only women need employ. Women, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, have no other weapon in their arsenal than to use their cunni to get what they want—or what some man wants them to get for him. The day I need to resort to sexual trickery to achieve my ends, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, is the day that I will put my sword through my belly. You have a proud name. But compared to mine it is less than the dust. You have impugned my dignitas. I will not rest until I have extirpated that stain. How I obtained your fleet is not your affair. Or Thermus’s! You may rest assured, however, that it was obtained honorably and without my needing to bed the King—or the Queen, for that matter. The sex of the one being exploited is of little moment. I do not reach my goals by such methods. I reach them by using my intelligence—a gift which, it seems to me, few men own. I should therefore go far. Further, probably, than you.”

Having finished, Caesar turned his back and looked at the receding siegeworks which were making a ruin of the outskirts of Mitylene. And Lucullus, winded, could only be thankful that the verbal exchange had taken place in Latin; otherwise the oarsmen would have spread its gist far and wide. Oh, thank you, Sulla! What a hornet you have sent to enliven our placid little investment! He will be more trouble than a thousand Mitylenes.

The rest of the trip was accomplished in a stony silence, Caesar withdrawn into himself and Lucullus cudgeling his brains to think of a way by which he could retrieve his position without sacrificing his good opinion of himself—for it was absolutely inconceivable that he, the commanding officer of this war, could lower himself to apologize to a junior military tribune. And, as a satisfactory solution continued to elude him, at the end of the short journey he scaled the ladder up onto the deck of the nearest sixteener having to pretend Caesar didn’t exist.

When he was standing firmly on the deck he held his right hand, palm outward, to halt Caesar’s progress up the ladder.

“Don’t bother, tribune,” he said coldly. “Return to my camp and find your quarters. I don’t want to see you.”

“Am I at liberty to find my servants and horses?”

“Of course.”

*

If Burgundus, who knew his master as well as anyone, was sure that something had gone very wrong during the time Caesar had been away from the fleet, he was wise enough not to remark upon Caesar’s pinched, glazed expression as they set off by land toward Lucullus’s camp.

Caesar himself remembered nothing of the ride, nor of the layout of the camp when he rode into it. A sentry pointed down the via principalis and informed the new junior military tribune that he would find his quarters in the second brick building on the right. It was not yet noon, but it felt as if the morning had contained a thousand hours, and the kind of weariness Caesar now found in himself was entirely new—dark, frightful, blind.

As this was a permanent camp not expected to be struck before the next spring, its inhabitants were housed more solidly and comfortably than under leather. For the rankers, endless rows of stout wooden huts, each containing eight soldiers; for the noncombatants, bigger wooden huts each containing eighty men; for the general, a proper house almost big enough to be called a mansion, built of sun—dried bricks; for the senior legates, a similar house; for the middle rank of officers, a squarer mud—brick pile four storeys in height; and for the junior military tribunes, the same kind of edifice, only smaller.

The door was open and voices issued from within when Caesar loomed there, hesitating, his servants and animals waiting in the road behind him.

At first he could see little of the interior, but his eyes were quick to respond to changes in the degree of available light, so he was able to take in the scene before anyone noticed him. A big wooden table stood in the middle of the room, around which, their booted feet on its top, sat seven young men. Who they were he didn’t know; that was the penalty for being the flamen Dialis. Then a pleasant—faced, sturdily built fellow on the far side of the table glanced at the doorway and saw Caesar.

“Hello!” he said cheerfully. “Come in, whoever you are.”

Caesar entered with far more assurance than he felt, the effect of Lucullus’s accusation still lingering in his face; the seven who stared at him saw a deadly Apollo, not a lyrical one. The feet came down slowly. After that initial welcome, no one said a word. Everyone just stared.

Then the pleasant—faced fellow got to his feet and came round the table, his hand outstretched. “Aulus Gabinius,” he said, and laughed. “Don’t look so haughty, whoever you—are! We’ve got enough of those already.”

Caesar took the hand, shook it strongly. “Gaius Julius Caesar,” he said, but could not answer the smile. “I think I’m supposed to be billeted here. A junior military tribune.”

“We knew they’d find an eighth somewhere,” said Gabinius, turning to face the others. “That’s all we are—junior military tribunes—the scum of the earth and a thorn in our general’s side. We do occasionally work! But since we’re not paid, the general can’t very well insist on it. We’ve just eaten dinner. There’s some left. But first, meet your fellow sufferers.”

The others by now had come to their feet.

“Gaius Octavius.” A short young man of muscular physique, Gaius Octavius was handsome in a rather Greek way, brown of hair and hazel of eye—except for his ears, which stuck straight out like jug handles. His handshake was nicely firm.

“Publius Cornelius Lentulus—plain Lentulus.” One of the haughty ones, obviously, and a typical Cornelian—brown of coloring, homely of face. He looked as if he had trouble keeping up, yet was determined to keep up—insecure but dogged.

“The fancy Lentulus—Lucius Cornelius Lentulus Niger. We call him Niger, of course.” Another of the haughty ones, another typical Cornelian. More arrogant than plain Lentulus.

“Lucius Marcius Philippus Junior. We call him Lippus—he’s such a snail.” The nickname was an unkindness, as Lippus did not have bleary eyes; rather, his eyes were quite magnificently large and dark and dreamy, set in a far better-looking face than Philippus owned—from his Claudian grandmother, of course, whom he resembled. He gave an impression of easygoing placidity and his handshake was gentle, though not weak.

“Marcus Valerius Messala Rufus. Known as Rufus the Red.” Not one of the haughty ones, though his patrician name was very haughty. Rufus the Red was a red man—red of hair and red of eye. He did not, however, seem to be red of disposition.

“And, last as usual because we always seem to look over the top of his head, Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus.”

Bibulus was the haughtiest one of all, perhaps because he was by far the smallest, diminutive in height and in build. His features lent themselves to a natural expression of superiority, for his cheekbones were sharp, as was his bumpy Roman nose; the mouth was discontented and the brows absolutely straight above slightly prominent, pale grey eyes. Hair and brows were white—fair, having no gold in them, which made him seem older than his years, numbering twenty-one.

Very occasionally two individuals upon meeting generate in that first glance a degree of dislike which has no foundation in fact or logic; it is instinctive and ineradicable. Such was the dislike which flared between Gaius Julius Caesar and Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus in their first exchange of glances. King Nicomedes had spoken of enemies—here was one, Caesar was sure.

Gabinius pulled the eighth chair from its position against the wall and set it at the table between his own and Octavius’s.

“Sit down and eat,” he said.

“I’ll sit, gladly, but forgive me if I don’t eat.”

“Wine, you’ll have some wine!”

“I never touch it.”

Octavius giggled. “Oh, you’ll love living here!” he cried. “The vomit is usually wall to wall.”

“You’re the flamen Dialis!” exclaimed Philippus’s son.

“I was the flamen Dialis,” said Caesar, intending to say no more. Then he thought better of that, and went on, “If I give you the details now, no one need ever ask about it again.” He told the story crisply, his words so well chosen that the rest of them—no scholars, any—soon realized the new tribune was an intellectual, if not a scholar.

“Quite a tale,” said Gabinius when it was over.

“So you’re still married to Cinna’s daughter,” said Bibulus.

“Yes.”

“And,” said Octavius, giving a whoop of laughter, “we are now hopelessly locked in the ancient combat, Gabinius! Caesar makes it four patricians! War to the death!”

The rest gave him withering glances, and he subsided.

“Just come out from Rome, have you?” asked Rufus.

“No, from Bithynia.”

“What were you doing in Bithynia?” asked plain Lentulus.

“Gathering a fleet for the investment of Mitylene.”

“I’ll bet that old pansy Nicomedes liked you,” sneered Bibulus. Knowing that it was a breach of manners calculated to offend most of those in the room, he had tried not to say it; but somehow his tongue could not resist.

“He did, as a matter of fact,” said Caesar coolly.

“Did you get your fleet?” Bibulus pressed.

“Naturally,” said Caesar with a haughtiness Bibulus could never have matched.

The laughter was sharp, like Bibulus’s face. “Naturally? Don’t you mean, un—naturally?”

No one actually saw what happened next. Six pairs of eyes only found focus after Caesar had moved around the table and picked Bibulus up bodily, holding him at arm’s length, feet well clear of the floor. It looked ridiculous, comedic; Bibulus’s arms were swinging wildly at Caesar’s smiling face but were too short to connect—a scene straight out of an inspired mime.

“If you were not as insignificant as a flea,” said Caesar, “I would now be outside pounding your face into the cobbles. Unfortunately, Pulex, that would be tantamount to murder. You’re too insignificant to allow me to beat you to a pulp. So stay out of my way, fleabite!” Still holding Bibulus clear of the floor, he looked about until he found something that would do—a cabinet six feet tall. Without seeming to exert much effort, he popped Bibulus on top, gracefully avoiding the boot Bibulus aimed at him. “Kick your feet up there for a while, Pulex.”

Then he was gone, out into the road.

“Pulex really suits you, Bibulus!” said Octavius, laughing. “I shall call you Pulex from now on, you deserve it. How about you, Gabinius? Going to call him Pulex?”

“I’d rather call him Podex!” snapped Gabinius, red-faced with anger. “What possessed you to say that, Bibulus? It was utterly uncalled for, and it makes every one of us look bad!” He glared at the others. “I don’t care what the rest of you do, but I’m going out to help Caesar unload.”

“Get me down!” said Bibulus from the top of the cabinet.

“Not I!” said Gabinius scornfully.

In the end no one volunteered; Bibulus had to drop cleanly to the floor, for the flimsy unit was too unstable to permit of his lowering himself by his hands. In the midst of his monumental rage he also knew bewilderment and mortification—Gabinius was right. What had possessed him? All he had succeeded in doing was making a churl of himself—he had lost the esteem of his companions and could not console himself that he had won the encounter, for he had not. Caesar had won it easily—and with honor—not by striking a man smaller than himself, but rather by showing that man’s smallness up. It was only natural that Bibulus should resent size and muscularity in others, as he had neither; the world, he well knew, belonged to big and imposing men. Just the look of Caesar had been enough to set him off—the face, the body, the height—and then, to cap those physical advantages, the fellow had produced a spate of fluent, beautifully chosen words! Not fair!

He didn’t know whom he hated most—himself, or Gaius Julius Caesar. The man with everything. Bellows of mirth were floating in from the road, too intriguing for Bibulus to resist. Quietly he crept to the side of the doorway and peered around it furtively. There stood his six fellow tribunes holding their sides, while the man who had everything sat upon the back of a mule! Whatever he was saying Bibulus could not hear, but he knew the words were witty, funny, charming, likable, irresistible, fascinating, interesting, superbly chosen, spellbinding.

“Well,’’ he said to himself as he slunk toward the privacy of his room, “he will never, never, never be rid of this flea!”

*

As winter set in and the investment of Mitylene slowed to that static phase wherein the besiegers simply sat and waited for the besieged to starve, Lucius Licinius Lucullus finally found time to write to his beloved Sulla.

I hold out high hopes for an end to this in the spring, thanks to a very surprising circumstance about which I would rather tell you a little further down the columns. First, I would like you to grant me a favor. If I do manage to end this in the spring, may I come home? It has been so long, dear Lucius Cornelius, and I need to set eyes on Rome—not to mention you. My brother, Varro Lucullus, is now old enough and experienced enough to be a curule aedile, and I have a fancy to share the curule aedileship with him. There is no other office a pair of brothers can share and earn approbation. Think of the games we will give! Not to mention the pleasure. I am thirty-eight now, my brother is thirty-six—almost praetor time, yet we have not been aediles. Our name demands that we be aediles. Please let us have this office, then let me be praetor as soon afterward as possible. If, however, you feel my request is not wise or not deserved, I will of course understand.

Thermus seems to be managing in Asia Province, having given me the siege of Mitylene to keep me busy and out of his hair. Not a bad sort of fellow, really. The local peoples all like him because he has the patience to listen to their tales of why they can’t afford to pay the tribute, and I like him because after he’s listened so patiently, he insists they pay the tribute.

These two legions I have here are composed of a rough lot of fellows. Murena had them in Cappadocia and Pontus, Fimbria before him. They have an independence of mind which I dislike, and am busy knocking out of them. Of course they resent your edict that they never be allowed to return to Italy because they condoned Fimbria’s murder of Flaccus, and send a deputation to me regularly asking that it be lifted. They get nowhere, and by this know me well enough to understand that I will decimate them if they give me half an excuse. They are Rome’s soldiers, and they will do as they are told. I become very testy when rankers and junior tribunes think they are entitled to a say—but more of that anon.

It seems to me at this stage that Mitylene will have softened to a workable consistency by the spring, when I intend a frontal assault. I will have several siege towers in place, so it ought to succeed. If I can beat this city into submission before the

summer, the rest of Asia Province will lie down tamely.

The main reason why I am so confident lies in the fact that I have the most superb fleet from—you’ll never guess!—Nicomedes! Thermus sent your nephew by marriage, Gaius Julius Caesar, to obtain it from Nicomedes at the end of Quinctilis. He did write to me to that effect, though neither of us expected to see the fleet before March or even April of next year. But apparently, if you please, Thermus had the audacity to laugh at young Caesar’s confidence that he would get the fleet together quickly. So Caesar pokered up and demanded a fleet size and delivery date from Thermus in the most high—handed manner possible. Forty ships, half of them decked quinqueremes or triremes, delivered on the Kalends of November. Such were Thermus’s orders to this haughty young fellow.

But would you believe it, Caesar turned up in my camp on the Kalends of November with a far better fleet than any Roman could ever have expected to get from the likes of Nicomedes? Including two sixteeners, for which I have to pay no more than food and wages for their crews! When I saw the bill, I was amazed—Bithynia will make a profit, but not an outrageous one. Which makes me honor—bound to return the fleet as soon as Mitylene falls. And to pay up. I hope to pay up out of the spoils, of course, but if these should fail to be as large as I expect, is there any chance you could persuade the Treasury to make me a special grant?

I must add that young Caesar was arrogant and insolent when he handed the fleet over to me. I was obliged to put him in his place. Naturally there is only one way he could possibly have extracted such a magnificent fleet in such a short time from old pansy Nicomedes—he slept with him. And so I told him, to put him in his place. But I doubt there is any way in the world to put Caesar in his place! He turned on me like a hooded snake and informed me that he didn’t need to resort to women’s tricks to obtain anything—and that the day he did was the day he would put his sword through his belly. He left me wondering how to discipline him—not usually a problem I have, as you know. In the end I thought perhaps his fellow junior military tribunes might do it for me. You remember them—you must have seen them in Rome before they set out for service. Gabinius, two Lentuli, Octavius, Messala Rufus, Bibulus, and Philippus’s son.

I gather tiny Bibulus did try. And got put up on top of a tall cabinet for his pains. The ranks in the junior tribunes’ quarters have been fairly split since—Caesar has acquired Gabinius, Octavius, and Philippus’s son—Rufus is neutral—and the two Lentuli and Bibulus loathe him. There is always trouble among young men during siege operations, of course, because of the boredom, and it’s difficult to flog the young villains to do any work. Even for me. But Caesar spells trouble above and beyond the usual. I detest having to bother myself with people on this low level, but I have had no choice on several occasions. Caesar is a handful. Too pretty, too self-confident, too aware of what is, alas, a very great intelligence.

However, to give Caesar his due, he’s a worker. He never stops. How I don’t quite know, but almost every ranker in the camp seems to know him—and like him, more’s the pity. He just takes charge. My legates have taken to avoiding him because he won’t take orders on a job unless he approves of the way the job is being done. And unfortunately his way is always the better way! He’s one of those fellows who has it all worked out in his mind before the first blow is struck or the first subordinate ordered to do a thing. The result is that all too often my legates end up with red faces.

The only way so far that I have managed to prick his confidence is in referring to how he obtained his wonderful fleet from old Nicomedes at such a bargain price. And it does work, to the extent that it angers him hugely. But will he do what I want him to do—physically attack me and give me an excuse to court—martial him? No! He’s too clever and too self-controlled. I don’t like him, of course. Do you? He had the impudence to inform me that my birth compared to his is less than the dust!

Enough of junior tribunes. I ought to find things to say about grander men—senior legates, for example. But I am afraid that about them I can think of nothing.