“You’ll have to go to Spain,” said Sulla to Metellus Pius. “Quintus Sertorius is rapidly taking the whole place over.”

Metellus Pius gazed at his superior somewhat reprovingly. “Surely not!” he said in reasonable tones. “He has fruh—fruh—friends among the Lusitani and he’s quite strong west of the Baetis, buh—buh—but you have good governors in both the Spanish provinces.”

“Do I really?” asked Sulla, mouth turned down. “Not anymore! I’ve just had word that Sertorius has trounced Lucius Fufidius after that fool was stupid enough to offer him battle. Four legions! Yet Fufidius couldn’t beat Sertorius in command of seven thousand men, only a third of whom were Roman!”

“He bruh—bruh—brought the Romans with him from Mauretania last spring, of course,” said Metellus Pius. “The rest are Lusitani?”

“Savages, dearest Piglet! Not worth one hobnail on the sole of a Roman caliga! But quite capable of beating Fufidius.”

“Oh… Edepol!”

For some reason beyond the Piglet, this delightfully mild expletive sent Sulla into paroxysms of laughter; some time elapsed before the Dictator could compose himself sufficiently to speak further upon the vexing subject of Quintus Sertorius.

“Look, Piglet, I know Quintus Sertorius of old. So do you! If Carbo could have kept him in Italy, I might not have won at the Colline Gate because I may well have found myself beaten long before then. Sertorius is at least Gaius Marius’s equal, and Spain is his old stamping ground. When Luscus drove him out of Spain last year, I’d hoped to see the wretched fellow degenerate into a Mauretanian mercenary and trouble us never again. But I ought to have known better. First he took Tingis off King Ascalis, then he killed Paccianus and stole his Roman troops. Now he’s back in Further Spain, busy turning the Lusitani into crack Roman troops. It will have to be you who goes to govern Further Spain—and at the start of the New Year, not in spring.” He picked up a single sheet of paper and waved it at Metellus Pius gleefully. “You can have eight legions! That’s eight less I have to find land for. And if you leave late in December, you can sail direct to Gades.”

“A great command,” said the Pontifex Maximus with genuine satisfaction, not at all averse to being out of Rome on a long campaign—even if that meant he had to fight Sertorius. No religious ceremonies to perform, no sleepless nights worrying as to whether his tongue would trip him up. In fact, the moment he got out of Rome, he knew his speech impediment would disappear—it always did. He bethought himself of something else. “Whom will you send to govern Nearer Spain?”

“Marcus Domitius Calvinus, I think.”

“Not Curio? He’s a guh—guh—guh—good general.”

“I have Africa in mind for Curio. Calvinus is a better man to support you through a major campaign, Piglet dear. Curio might prove too independent in his thinking,” said Sulla.

“I do see what you mean.”

“Calvinus can have a further six legions. That’s fourteen altogether. Surely enough to tame Sertorius!”

“In no time!” said the Piglet warmly. “Fuh—fuh—fear not, Lucius Cornelius! Spain is suh—suh—safe!”

Again Sulla began to laugh. “Why do I care? I don’t know why I care, Piglet, and that’s the truth! I’ll be dead before you come back.”

Shocked, Metellus Pius put out his hands in protest. “No! Nonsense! You’re still a relatively young man!”

“It was foretold that I would die at the height of my fame and power,” said Sulla, displaying no fear or regret. “I shall step down next Quinctilis, Pius, and retire to Misenum for one last, glorious fling. It won’t be a long fling, but I am going to enjoy every single moment!”

“Prophets are un—Roman,” said Metellus Pius austerely. “We both know they’re more often wrong than right.”

“Not this prophet,” said Sulla firmly. “He was a Chaldaean, and seer to the King of the Parthians.”

Deeming it wiser, Metellus Pius gave the argument up; he settled instead to a discussion of the coming Spanish campaign.

*

In truth, Sulla’s work was winding down to inertia. The spate of legislation was over and the new constitution looked as if it would hold together even after he was gone; even the apportioning of land to his veterans was beginning to arrive at a stage where Sulla himself could withdraw from the business, and Volaterrae had finally fallen. Only Nola—oldest and best foe among the cities of Italy—still held out against Rome.

He had done what he could, and overlooked very little. The Senate was docile, the Assemblies virtually impotent, the tribunes of the plebs mere figureheads, his courts a popular as well as a practical success, and the future governors of provinces hamstrung. The Treasury was full, and its bureaucrats mercilessly obliged to fall into proper practices of accounting. If the Ordo Equester didn’t think the loss of sixteen hundred knights who had fallen victim to Sulla’s proscriptions was enough of a lesson, Sulla drove it home by stripping the knights of the Public Horse of all their social privileges, then directed that all men exiled by courts staffed by knight juries should come home.

He had crotchets, of course. Women suffered yet again when he forbade any female guilty of adultery to remarry. Gambling (which he abhorred) was forbidden on all events except boxing matches and human footraces, neither of which drew a crowd, as he well knew. But his chief crotchet was the public servant, whom he despised as disorganized, slipshod, lazy, and venal. So he regulated every aspect of the working lives of Rome’s secretaries, clerks, scribes, accountants, heralds, lictors, messengers, the priestly attendants called calatores, the men who reminded other men of yet other men’s names—nomenclatores—and general public servants who had no real job description beyond the fact that they were apparitores. In future, none of these men would know whose service they would enter when the new magistrates came into office; no magistrate could ask for public servants by name. Lots would be drawn three years in advance, and no group would consistently serve the same sort of magistrate.

He found new ways to annoy the Senate, having already banned every noisy demonstration of approbation or disapproval and changed the order in which senators spoke; now he put a law on the tablets which severely affected the incomes of certain needy senators by limiting the amount of money provincial delegations could spend when they came to Rome to sing the praises of an ex-governor, which meant these delegations could not (as they had in the past) give money to certain needy senators.

It was a full program of laws which covered every aspect of Roman public life as well as much Roman life hitherto private. Everyone knew the parameters of his lot—how much he could spend, how much he could take, how much he paid the Treasury, who he could marry, whereabouts he would be tried, and what he would be tried for. A massive undertaking executed, it seemed, virtually single—handed. The knights were down, but military heroes were up, up, up. The Plebeian Assembly and its tribunes were down, but the Senate was up, up, up. Those closely related to the proscribed were down, but men like Pompey the Great were up, up, up. The advocates who had excelled in the Assemblies (like Quintus Hortensius) were down, but the advocates who excelled in the more intimate atmosphere of the courts (like Cicero) were up, up, up.

“Little wonder that Rome is reeling, though I don’t hear a single voice crying Sulla nay,” said the new consul, Appius Claudius Pulcher, to his colleague in the consulship, Publius Servilius Vatia.

“One reason for that,” said Vatia, “lies in the good sense behind so much of what he has legislated. He is a wonder!”

Appius Claudius nodded without enthusiasm, but Vatia didn’t misinterpret this apathy; his colleague was not well, had not been well since his return from the inevitable siege of Nola which he seemed to have supervised on and off for a full ten years. He was, besides, a widower burdened with six children who were already notorious for their lack of discipline and a distressing tendency to conduct their tempestuous and deadly battles in public.

Taking pity on him, Vatia patted his back cheerfully. “Oh, come, Appius Claudius, look at your future more brightly, do! It’s been long and hard for you, but you’ve finally arrived.”

“I won’t have arrived until I restore my family’s fortune,” said Appius Claudius morosely. “That vile wretch Philippus took everything I had and gave it to Cinna and Carbo—and Sulla has not given it back.”

“You should have reminded him,” said Vatia reasonably. “He has had a great deal to do, you know. Why didn’t you buy up big during the proscriptions?”

“I was at Nola, if you remember,” said the unhappy one.

“Next year you’ll be sent to govern a province, and that will set all to rights.”

“If my health holds up.”

“Oh, Appius Claudius! Stop glooming! You’ll survive!”

“I can’t be sure of that” was the pessimistic reply. “With my luck, I’ll be sent to Further Spain to replace Pius.”

“You won’t, I promise you,” soothed Vatia. “If you won’t ask Lucius Cornelius on your own behalf, I will! And I’ll ask him to give you Macedonia. That’s always good for a few bags of gold and a great many important local contracts. Not to mention selling citizenships to rich Greeks.”

“I didn’t think there were any,” said Appius Claudius.

“There are always rich men, even in the poorest countries. It is the nature of some men to make money. Even the Greeks, with all their political idealism, failed to legislate the wealthy man out of existence. He’d pop up in Plato’s Republic, I promise you!”

“Like Crassus, you mean.”

“An excellent example! Any other man would have plummeted into obscurity after Sulla cut him dead, but not our Crassus!”

They were in the Curia Hostilia, where the New Year’s Day inaugural meeting of the Senate was being held because there was no temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, and the size of the Senate had grown sufficiently to render places like Jupiter Stator and Castor’s too small for a comfortable meeting that was to be followed by a feast.

“Hush!” said Appius Claudius. “Sulla is going to speak.”

“Well, Conscript Fathers,” the Dictator commenced, voice jovial, “basically it is all done. It was my avowed intention to set Rome back on her feet and make new laws for her that fulfilled the needs of the mos maiorum. I have done so. But I will continue as Dictator until Quinctilis, when I will hold the elections for the magistrates of next year. This you already know. However, I believe some of you refuse to credit that a man endowed with such power would ever be foolish enough to step down. So I repeat that I will step down from the Dictatorship after the elections in Quinctilis. This means that next year’s magistrates will be the last personally chosen by me. In future years all the elections will be free, open to as many candidates as want to stand. There are those who have consistently disapproved of the Dictator’s choosing his magistrates, and putting up only as many names for voting as there are jobs to fill. But—as I have always maintained!—the Dictator must work with men who are prepared to back him wholeheartedly. The electorate cannot be relied upon to return the best men, nor even the men who are overdue for office and entitled to that office by virtue of their rank and experience. So as the Dictator I have been able to ensure I have both the men I wish to work with and to whom office was morally and ethically owed. Like my dear absent Pontifex Maximus, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius. He continues to be worthy of my favor, for he is already on the way to Further Spain, there to contend with the outlawed felon, Quintus Sertorius.”

“He’s rambling a bit,” said Catulus clinically.

“Because he has nothing to say,” said Hortensius.

“Except that he will stand down in Quinctilis.”

“And I am actually beginning to believe that.”

*

But that New Year’s Day, so auspiciously begun, was to end with some long—delayed bad news from Alexandria.

Ptolemy Alexander the Younger’s time had finally come at the beginning of the year just gone, the second year of Sulla’s reign. Word had arrived then from Alexandria that King Ptolemy Soter Chickpea was dead and his daughter Queen Berenice now ruling alone. Though the throne came through her, under Egyptian law she could not occupy it without a king. Might, the embassage from Alexandria humbly asked, Lucius Cornelius Sulla grant Egypt a new king in the person of Ptolemy Alexander the Younger?

“What happens if I deny you?’’ asked Sulla.

“Then King Mithridates and King Tigranes will win Egypt,” said the leader of the delegation. “The throne must be occupied by a member of the Ptolemaic dynasty. If Ptolemy Alexander is not made King and Pharaoh, then we will have to send to Mithridates and Tigranes for the elder of the two bastards, Ptolemy Philadelphus who was called Auletes because of his piping voice.”

“I can see that a bastard might be able to assume the title of King, but can he legally become Pharaoh?” asked Sulla, thus revealing that he had studied the Egyptian monarchy.

“Were he the son of a common woman, definitely not’’ was the answer. “However, Auletes and his younger brother are the sons of Ptolemy Soter and Princess Arsinoe, the royal concubine who was the eldest legitimate daughter of the King of Nabataea. It has long been the custom for all the small dynasts of Arabia and Palestina to send their oldest daughters to the Pharaoh of Egypt as his concubines, for that is a more august and respectable fate than marriage to other small dynasts—and brings greater security to their fathers, who all need Egyptian co-operation to carry on their trading activities up the Sinus Arabicus and across the various deserts.”

“So you’re saying that Alexandria and Egypt would accept one of the Ptolemaic bastards because his mother was royal?’’

“In the event that we cannot have Ptolemy Alexander, that is inevitable, Lucius Cornelius.”

“Mithridatid and Tigranic puppets,” said Sulla thoughtfully.

“As their wives are the daughters of Mithridates, that too is inevitable. Tigranes is now too close to the Egyptian border for us to insist the Ptolemy bastards divorce these girls. He would invade in the name of Mithridates. And Egypt would fall. We are not militarily strong enough to deal with a war of that magnitude. Besides which, the girls have sufficient Ptolemaic blood to pass on the throne. In the event,” said the delegation’s leader suavely, “that the child of Ptolemy Soter and his concubine the daughter of the King of Idumaea fails to grow up and provide Auletes with a wife of half—Ptolemaic blood.”

Sulla looked suddenly brisk and businesslike. “Leave it with me, I’ll attend to the matter. We can’t have Armenia and Pontus in control of Egypt!”

His own deliberations were already concluded long since, so without delay Sulla set off for the villa on the Pincian Hill and an interview with Ptolemy Alexander.

“Your day has arrived,” said the Dictator to his hostage, no longer such a very young man; he had turned thirty-five.

“Chickpea is dead?” asked Ptolemy Alexander eagerly.

“Dead and entombed. Queen Berenice rules alone.”

“Then I must go!” Ptolemy Alexander squawked, agitated. “I must go! There is no time to be wasted!”

“You can go when I say you can go, not a moment before,” said Sulla harshly. “Sit down, Your Majesty, and listen to me.”

His Majesty sat with his draperies flattening limply around him like a pricked puffball, his eyes very strange between the solid lines of stibium he had painted on both upper and lower lids, extended out toward the temples in imitation of the antique Eye of Egypt, the wadjet; as he had also painted in thick black brows and whitened the area between them and the black line of the upper lids, Sulla found it absolutely impossible to decide what Ptolemy Alexander’s real eyes held. The whole effect, he decided, was distinctly sinister—and probably intended to be.

“You cannot talk to a king as to an inferior,” said His Majesty stiffly.

“There is no king in all the world who is not my inferior,” Sulla answered contemptuously. “I rule Rome! That makes me the most powerful man between the Rivers of Ocean and Indus. So you will listen, Your Majesty—and without interrupting me! You may go to Alexandria and assume the throne. But only upon certain conditions. Is that understood?”

“What conditions?’’

“That you make your will and lodge it with the Vestal Virgins here in Rome. It need only be a simple will. In the event that you die without legitimate issue, you will bequeath the Kingdom of Egypt to Rome.”

Ptolemy Alexander gasped. “I can’t do that!”

“You can do anything I say you must do—if you want to rule in Alexandria. That is my price. Egypt to fall to Rome if you die without legitimate issue.”

The unsettling eyes within their embossed ritual framework slid from side to side, and the richly carmined mouth—full and self-indulgent—worked upon itself in a way which reminded Sulla of Philippus. “All right, I agree to your price.” Ptolemy Alexander shrugged. “I don’t subscribe to the old Egyptian religion, so what can it matter to me after I’m dead?”

“Excellently reasoned!” said Sulla heartily. “I brought my secretary with me so you’d be able to make out the document here and now. With every royal seal and your personal cartouche attached, of course. I want no arguments from the Alexandrians after you’re dead.” He clapped for a Ptolemaic servant, and asked that his own secretary be summoned. As they waited he said idly, “There is one other condition, actually.”

“What?” asked Ptolemy Alexander warily.

“I believe that in a bank at Tyre you have a sum of two thousand talents of gold deposited by your grandmother, the third Queen Cleopatra. Mithridates got the money she left on Cos, but not what she left at Tyre. And King Tigranes has not yet managed to subdue the cities of Phoenicia. He’s too busy with the Jews. You will leave those two thousand talents of gold to Rome.”

One look at Sulla’s face informed His Majesty that there could be no argument; he shrugged again, nodded.

Flosculus the secretary came, Ptolemy Alexander sent one of his own slaves for his seals and cartouche, and the will was soon made and signed and witnessed.

“I will lodge it for you,” said Sulla, rising, “as you cannot cross the pomerium to visit Vesta.”

Two days later Ptolemy Alexander the Younger departed from Rome with the delegation, and took ship in Puteoli for Africa; it was easier to cross the Middle Sea at this point and then to hug the African coast from the Roman province to Cyrenaica, and Cyrenaica to Alexandria. Besides which, the new King of Egypt wanted to go nowhere near Mithridates or Tigranes, and did not trust to his luck.

In the spring an urgent message had come from Alexandria, where Rome’s agent (a Roman ostensibly in trade) had written that King Ptolemy Alexander the Second had suffered a disaster. Arriving safely after a long voyage, he had immediately married his half sister cum first cousin, Queen Berenice. For exactly nineteen days he had reigned as King of Egypt, nineteen days during which, it seemed, he conceived a steadily increasing hatred of his wife. So early on the nineteenth day of his reign, apparently considering this female creature a nonentity, he murdered his forty-year-old wife/sister/cousin/queen. But she had reigned for a long time in conjunction with her father, Chickpea; the citizens of Alexandria adored her. Later during the nineteenth day of his reign the citizens of Alexandria stormed the palace, abducted King Ptolemy Alexander the Second, and literally tore him into small pieces—a kind of free—for—all fun—for—all celebration staged in the agora. Egypt was without king or queen, and in a state of chaos.

“Splendid!” cried Sulla as he read his agent’s letter, and sent off an embassage of Roman senators led by the consular and ex-censor Marcus Perperna to Alexandria, bearing King Ptolemy Alexander the Second’s last will and legal testament. His ambassadors were also under orders to call in at Tyre on the way home, there to pick up the gold.

From that day to this New Year’s Day of the third year of Sulla’s reign, nothing further had been heard.

“Our entire journey has been dogged by ill luck,” said Marcus Perperna. “We were shipwrecked off Crete and taken captive by pirates—it took two months for the cities of Peloponnesian Greece to raise our ransoms, and then we had to finish the voyage by sailing to Cyrene and hugging the Libyan coast to Alexandria.”

“In a pirate vessel?” asked Sulla, aware of the gravity of this news, but nonetheless inclined to laugh; Perperna looked so old and shrunken—and terrified!

“As you so shrewdly surmise, in a pirate vessel.”

“And what happened when you reached Alexandria?”

“Nothing good, Lucius Cornelius. Nothing good!” Perperna heaved a huge sigh. “We found the Alexandrians had acted with celerity and efficiency. They knew exactly whereabouts to send after King Ptolemy Alexander was murdered.”

“Send for what, Perperna?”

“Send for the two bastard sons of Ptolemy Soter Chickpea, Lucius Cornelius. They petitioned King Tigranes in Syria to give them both young men—the elder to rule Egypt, and the younger to rule Cyprus.”

“Clever, but not unexpected,” said Sulla. “Go on.”

“By the time we reached Alexandria, King Ptolemy Auletes was already on the throne, and his wife—the daughter of King Mithridates—was beside him as Queen Cleopatra Tryphaena. His younger brother—whom the Alexandrians have decided to call Ptolemy the Cyprian—was sent to be regent of Cyprus. His wife—another daughter of Mithridates—went with him.”

“And her name is?”

“Mithridatidis Nyssa.”

“The whole thing is illegal,” said Sulla, frowning.

“Not according to the Alexandrians!”

“Go on, Perperna, go on! Tell me the worst.”

“Well, we produced the will, of course. And informed the Alexandrians that we had come formally to annex the Kingdom of Egypt into the empire of Rome as a province.”

“And what did they say to that, Perperna?”

“They laughed at us, Lucius Cornelius. By various methods their lawyers proceeded to prove that the will was invalid, then they pointed to the King and Queen upon their thrones and showed us that they had found legitimate heirs.”

“But they’re not legitimate!”

“Only under Roman law, they said, and denied that it applied to Egypt. Under Egyptian law—which seems to consist largely of rules made up on the spur of the moment to support whatever the Alexandrians have in mind—the King and Queen are legitimate.”

“So what did you do, Perperna?”

“What could I do, Lucius Cornelius? Alexandria was crawling with soldiers! We thanked our Roman gods that we managed to get out of Egypt alive, and with our persons intact.”

“Quite right,” said Sulla, who did not bother venting his spleen upon unworthy objects. “However, the fact remains that the will is valid. Egypt now belongs to Rome.” He drummed his fingers on his desk. “Unfortunately there isn’t much Rome can do at the present time. I’ve had to send fourteen legions to Spain to deal with Quintus Sertorius, and I’ve no wish to add to the Treasury’s expenses by mounting another campaign at the opposite end of the world. Not with Tigranes riding roughshod over most of Syria and no curb in the vicinity now that the Parthian heirs are so embroiled in civil war. Have you still got the will?”

“Oh yes, Lucius Cornelius.”

“Then tomorrow I’ll inform the Senate what’s happened and give the will back to the Vestals against the day when Rome can afford to annex Egypt by force—which is the only way we’re going to come into our inheritance, I think.”

“Egypt is fabulously rich.”

“That’s no news to me, Perperna! The Ptolemies are sitting on the greatest treasure in the world, as well as one of the world’s richest countries.” Sulla assumed the expression which indicated he was finished, but said, it appeared as an afterthought, “I suppose that means you didn’t obtain the two thousand talents of gold from Tyre?’’

“Oh, we got that without any trouble, Lucius Cornelius,” said Perperna, shocked. “The bankers handed it over the moment we produced the will. On our way home, as you instructed.”

Sulla roared with laughter. “Well done for you, Perperna! I can almost forgive you the debacle in Alexandria!” He got up, rubbing his hands together in glee. “A welcome addition to the Treasury. And so the Senate will see it, I’m sure. At least poor Rome didn’t have to pay for an embassage without seeing an adequate financial return.”

*

All the eastern kings were being troublesome—one of the penalties Rome was forced to endure because her internecine strife had made it impossible for Sulla to remain in the east long enough to render both Mithridates and Tigranes permanently impotent. As it was, no sooner had Sulla sailed home than Mithridates was back intriguing to annex Cappadocia, and Lucius Licinius Murena (then governor of Asia Province and Cilicia) had promptly gone to war against him—without Sulla’s knowledge or permission, and in contravention of the Treaty of Dardanus. For a while Murena had done amazingly well, until self-confidence had led him into a series of disastrous encounters with Mithridates on his own soil of Pontus. Sulla had been obliged to send the elder Aulus Gabinius to order Murena back to his own provinces. It had been Sulla’s intention to punish Murena for his cavalier behavior, but then had come the confrontation with Pompey; so Murena had had to be allowed to return and celebrate a triumph in order to put Pompey in his place.

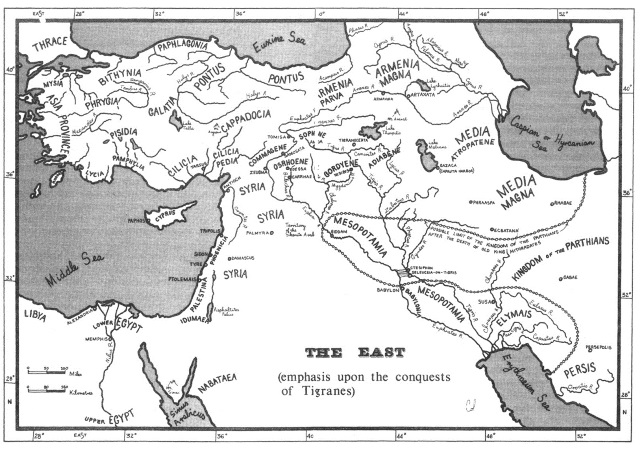

In the meantime, Tigranes had used the six years just gone by to expand his kingdom of Armenia southward and westward into lands belonging to the King of the Parthians and the rapidly disintegrating Kingdom of Syria. He had begun to see his chance when he learned that old King Mithradates of the Parthians was too ill to proceed with a projected invasion of Syria—and too ill to prevent the barbarians called Massagetae from taking over all his lands to the north and east of Parthia itself, as well as to prevent one of his sons, Gotarzes, from usurping Babylonia.

As Tigranes himself had once predicted, the death of King Mithradates of the Parthians had provoked a war of succession complicated by the fact that the old man had had three official queens—two his paternal half sisters, and the third none other than a daughter of Tigranes called Automa. While various sons of various mothers fought over what remained, yet another vital satrapy seceded—fabulously rich Elymais, watered by the eastern tributaries of the Tigris, the rivers Choaspes and Pasitigris; the silt—free harbors to the east of the Tigris—Euphrates delta were lost, as was the city of Susa, one of the Parthian royal seats. Uncaring, the sons of old King Mithradates warred on.

So did Tigranes. His first move (in the year Gaius Marius died) was to invade in succession the petty kingdoms of Sophene, Gordyene, Adiabene, and finally Osrhoene. These four little states conquered, Tigranes now owned all the lands bordering the eastern bank of the Euphrates from above Tomisa all the way down to Europus; the big cities of Amida, Edessa and Nisibis were now also his, as were the tolls levied along the great river. But rather than entrust such commercial enterprises as toll collecting to his own Armenians, Tigranes wooed and won over the Skenite Arabs who controlled the arid regions between the Euphrates and the Tigris south of Osrhoene, and exacted tolls on every caravan which passed across their territory. Nomad Bedouins though they were, Tigranes moved the Skenite Arabs into Edessa and Carrhae and appointed them the collectors of Euphrates tolls at Samosata and Zeugma. Their king—whose royal title was Abgar—was now the client of Tigranes, and the Greek—speaking populations of all the towns the King of Armenia had overcome were forced to emigrate to those parts of Armenia where the Greek language was hitherto unknown. Tigranes desperately wanted to be the civilized ruler of a Hellenized kingdom—and what better way to Hellenize it than to implant colonies of Greek speakers within its borders?

As a child Tigranes had been held hostage by the King of the Parthians and had lived in Seleuceia—upon—Tigris, far away from Armenia. At the time of his father’s death he was the only living son, but the King of the Parthians had demanded a huge price for releasing the youth Tigranes—seventy valleys in the richest part of Armenia, which was Media Atropatene. Now Tigranes marched into Media Atropatene and took back the seventy valleys, stuffed with gold, lapis lazuli, turquoise and fertile pastures.

He now found, however, that he lacked sufficient Nesaean horses to mount his growing numbers of cataphracts. These strange cavalrymen were clad from head to foot in steel—mesh armor—as were their horses, which needed to be large to carry the weight. So in the following year Tigranes invaded Media itself, the home of the Nesaean horse, and annexed it to Armenia. Ecbatana, summer royal seat of the Kings of the Parthians—and before them, the summer royal seat of the Kings of Media and Persia, including Alexander the Great—was burned to the ground, and its magnificent palace sacked.

Three years had gone by. While Sulla marched slowly up the Italian peninsula, Tigranes had turned his attention to the west and crossed the Euphrates into Commagene. Unopposed, he occupied all the lands of northern Syria between the Amanus Mountains and the Libanus Mountains, including mighty Antioch and the lower half of the valley of the Orontes River. Even a part of Cilicia Pedia fell to him, around the eastern shore of the Sinus Issicus.

Syria was genuine Hellenized territory, its populace a fully Greek—speaking one powerfully under the influence of Greek customs. No sooner had he established his authority in Syria than Tigranes uplifted whole communities of these hapless Greek—speakers and sent them and their families to live in his newly built capital of Tigranocerta. Most favored were the artisans, not one of whom was allowed to remain in Syria. However, the King understood the need to protect his Greek imports from his Median—speaking native peoples, who were directed under pain of death to treat the new citizens with care and kindness.

And while Sulla was legislating to have himself appointed Dictator of Rome, Tigranes formally adopted the title he had hungered for all his life—King of Kings. Queen Cleopatra Selene of Syria—youngest sister and at one time wife of Ptolemy Soter Chickpea—who had managed to rule Syria through several Seleucid husbands, was taken from Antioch and made to live in the humblest circumstances in a tiny village on the Euphrates; her place in the palace at Antioch was taken by the satrap Magadates, who was to rule Syria in the name of Tigranes, King of Kings.

King of Kings, thought Sulla cynically; all those eastern potentates thought themselves King of Kings. Even, it seemed, the two bastard sons of Ptolemy Soter Chickpea, who now ruled in Egypt and Cyprus with their Mithridatid wives. But the will of the dead Ptolemy Alexander the Second was genuine; no one knew that better than Sulla did, for he was its witness. Sooner or later Egypt would belong to Rome. For the moment Ptolemy Auletes must be allowed to reign in Alexandria; but, vowed Sulla, that puppet of Mithridates and Tigranes would never know an easy moment! The Senate of Rome would send regularly to Alexandria demanding that Ptolemy Auletes step down in favor of Rome, the true owner of Egypt.

As for King Mithridates of Pontus—interesting, that he had lost two hundred thousand men in the freezing cold of the Caucasus—he would have to be discouraged yet again from trying to annex Cappadocia. Complaining by letter to Sulla that Murena had plundered and burned four hundred villages along the Halys River, Mithridates had proceeded to take the Cappadocian bank of the Halys off poor Cappadocia; to make this ploy look legitimate, he had given King Ariobarzanes of Cappadocia a new bride, one of his own daughters. When Sulla discovered that the girl was a four-year-old child, he sent yet another messenger to see King Mithridates and order him in Rome’s name to quit Cappadocia absolutely, bride or no bride. The messenger had returned very recently, bearing a letter from Mithridates promising to do as he was told—and informing Sulla that the King of Pontus was going to send an embassage to Rome to ratify the Treaty of Dardanus into watertight legality.

“He’d better make sure his embassage doesn’t dawdle,” said Sulla to himself as he terminated all these thoughts of eastern kings by going to find his wife. It was in her presence—for she wasn’t very far away—that he ended his audible reflections by saying, “If they do dawdle, they won’t find me here to dicker with them—and good luck dickering with the Senate!”

“I beg your pardon, my love?” asked Valeria, startled.

“Nothing. Give me a kiss.”

*

Her kisses were nice enough. Just as she was nice enough, Valeria Messala. So far Sulla had found this fourth marriage a pleasant experience. But not a stimulating one. A part of that was due to his age and his illnesses, he was aware; but a larger part of it was due to the seductive and sensuous shortcomings of aristocratic Roman women, who just could not relax sufficiently in bed to enter into the kind of sexual cavorting the Dictator hankered after. His prowess was flagging: he needed to be stimulated! Why was it that women could love a man madly, yet not enter wholeheartedly into his sexual wants?

“I believe,” said Varro, who was the hapless recipient of this question, “that women are passive vessels, Lucius Cornelius. They are made to hold things, from a man’s penis to a baby. And the one who holds things is passive. Must be passive! Otherwise the hold is not stable. It is the same with animals. The male is the active participant, and must rid himself of his excessive desires by rutting with many different females.”

He had come to inform Sulla that Pompey was coming to Rome on a brief visit, and to enquire whether Sulla would like to see the young man. Instead of being given an audience, however, he found himself the audience, and had not yet managed to find the right moment to put his own query forward.

The darkened brows wriggled expressively. “Do you mean, my dear Varro, that a decently married man must rut with half of female Rome?”

“No, no, of course not!” gasped Varro. “All females are passive, so he could not find satisfaction!”

“Then do you mean that if a man wants his fleshly urges gratified to complete satiation, he ought to seek his sexual partners among men?” Sulla asked, face serious.

“Ooh! Ah! Um!” squeaked Varro, writhing like a centipede pinned through its middle. “No, Lucius Cornelius, of course not! Definitely not!”

“Then what is a decently married man to do?’’

“I am a student of natural phenomena, I know, but these are questions I am not qualified or skilled enough to answer!” babbled Varro, wishing he had not decided to visit this uncomfortable, perplexing man. The trouble was that ever since the months during which he, Varro, had anointed Sulla’s disintegrating face, Sulla had displayed a great fondness for him, and tended to become offended if Varro didn’t call to pay his respects.

“Calm down, Varro, I’m teasing you!” said Sulla, laughing.

“One never knows with you, Lucius Cornelius.” Varro wet his lips, began to formulate in his mind the words which would put his announcement of Pompey’s advent in the most favorable light; no fool, Varro was well aware that the Dictator’s feelings toward Pompey were ambivalent.

“I hear,” said Sulla, unconscious of all this mental juggling of a simple sentence, “that Varro Lucullus has managed to get rid of his adoptive sister—your cousin, I believe.”

“Terentia, you mean?” Varro’s face lit up. “Oh, yes! A truly wonderful stroke of luck!”

“It’s a long time,” said the smiling Sulla, who adored all sorts of gossip these days, “since a woman as rich as Terentia has had so much trouble finding a husband.”

“That’s not quite the situation,” said Varro, temporizing. “One can always find a man willing to marry a rich woman. The trouble with Terentia—who is Rome’s worst shrew, I grant you!—has forever been that she refused to look at any of the men her family found for her.”

Sulla’s smile had become a grin. “She preferred to stay at home and make Varro Lucullus’s life a misery, you mean.”

“Perhaps. Though she likes him well enough, I think. Her nature is at fault—and what can she do about that, since it was given to her at her birth?”

“Then what happened? Love at first sight?”

“Certainly not. The match was proposed by our swindling friend, Titus Pomponius who is now called Atticus because of his affection for Athens. Apparently he and Marcus Tullius Cicero have known each other for many years. Since you regulated Rome, Lucius Cornelius, Atticus visits Rome at least once a year.’’

“I am aware of it,” said Sulla, who didn’t hold Atticus’s financial flutterings against him any more than he did Crassus’s—it was the way Crassus had manipulated the proscriptions for his own gain caused his fall from Sulla’s grace.

“Anyway, Cicero’s legal reputation has soared. So have his ambitions. But his purse is empty. He needed to marry an heiress, though it looked as if she would have to be one of those abysmally undistinguished girls our less salubrious plutocrats seem to produce in abundance. Then Atticus suggested Terentia.” Varro stopped to look enquiringly at Sulla. “Do you know Marcus Tullius Cicero at all?” he asked.

“Quite well when he was a lad. My late son—who would be about the same age had he lived—befriended him. He was thought a prodigy then. But between my son’s death and the case of Sextus Roscius of Ameria, I saw him only as a contubernalis on my staff in Campania during the Italian War. Maturity hasn’t changed him. He’s just found his natural milieu, is all. He’s as pedantic, talkative, and full of his own importance as he ever was. Qualities which stand him in good stead as an advocate! However, I admit freely that he has a magnificent turn of phrase. And he does have a mind! His worst fault is that he’s related to Gaius Marius. They’re both from Arpinum.”

Varro nodded. “Atticus approached Varro Lucullus, who agreed to press Cicero’s suit with Terentia. And much to his surprise, she asked to meet Cicero! She had heard of his courtroom prowess, and told Varro Lucullus that she was determined to marry a man who was capable of fame. Cicero, she said, might be such a one.”

“How big is her dowry?”

“Enormous! Two hundred talents.”

“The line of her suitors must stretch right round the block! And must contain some very pretty, smooth fellows. I begin to respect Terentia, if she’s been proof against Rome’s most expert fortune hunters,” said Sulla.

“Terentia,” said her cousin deliberately, “is ugly, sour, cantankerous and parsimonious. She is now twenty-one years old, and still single. I know girls are supposed to obey their paterfamilias and marry whomsoever they are told to marry, but there is no man—alive or dead!—who could order Terentia to do anything she didn’t want to do.”

“And poor Varro Lucullus is such a nice man,” said Sulla, highly entertained.

“Precisely.”

“So Terentia met Cicero?”

“She did indeed. And—you could have bowled all of us over with a feather!—consented to marry him.”

“Lucky Cicero! One of Fortune’s favorites. Her money will come in very handy.”

“That’s what you think,” said Varro grimly. “She’s made up the marriage contract herself and retained complete control of her wealth, though she did agree to dower any daughters she might have, and contribute toward funding the careers of any sons. But as for Cicero—he’s not the man to get the better of Terentia!”

“What’s he like as a person these days, Varro?”

“Pleasant enough. Soft inside, I think. But vainglorious. Insufferably conceited about his intellect and convinced it has no peer. An avid social climber … Hates to be reminded that Gaius Marius is his distant relative! If Terentia had been one of those abysmally undistinguished daughters of our less salubrious plutocrats, I don’t think he would have looked at her. But her mother was a patrician and once married to Quintus Fabius Maximus, which means Fabia the Vestal Virgin is her half sister. Therefore Terentia was ‘good enough,’ if you know what I mean.” Varro pulled a face. “Cicero is an Icarus, Lucius Cornelius. He intends to fly right up into the realm of the sun—a dangerous business if you’re a New Man without a sestertius.”

“Whatever is in the air of Arpinum, it seems to breed such fellows,” said Sulla. “As well for Rome that this New Man from Arpinum has no military skills!”

“Quite the opposite, I have heard.”

“Oh, I know it! When he was my contubernalis he acted as my secretary. The sight of a sword made him ashen. But I’ve never had a better secretary! When is the wedding?”

“Not until after Varro Lucullus and his brother celebrate the ludi Romani in September.” Varro laughed. “There’s no room in their world at the moment for anything except planning the best games Rome has seen in a century—if at all!”

“A pity I won’t be in Rome to see them,” said Sulla, who did not look brokenhearted.

A small silence fell, which Varro took advantage of before Sulla could think of some other subject. “Lucius Cornelius, I wondered if you knew that Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus is coming to Rome shortly?” he asked diffidently. “He would like to call to see you, but understands how busy you are.”

“Never too busy to see Magnus!” said Sulla cheerfully. He directed a keen look at Varro. “Still running round after him with a pen and paper to record his every fart, Varro?”

A deep red suffused Varro’s skin; when dealing with Sulla one didn’t always know how he would see even the most innocent things. Did he, for example, think that Varro’s time would be better spent recording the deeds (or farts) of Lucius Cornelius Sulla? So he said, very humbly, “I do from time to time. It started as an accident because we were together when war broke out, and I was not proof against Pompeius’s enthusiasm. He said I should write history, not natural history. And that is what I do. I am not Pompeius’s biographer!”

“Very well answered!”

Thus it was that when Varro left the Dictator’s house on the Palatine, he had to pause to wipe the sweat from his face. They talked endlessly about the lion and the fox in Sulla; but personally Varro thought the worst beast he harbored was a common cat.

He had done well, however. When Pompey arrived in Rome with his wife and took up residence in his family’s house on the Carinae, Varro was able to say that Sulla would be glad to see Pompey, and would allocate him sufficient time for a cozy chat. That was Sulla’s phrase—but uttered with tongue in cheek, Varro knew. A cozy chat with Sulla could turn out to be a walk along a tightrope above a pit of burning coals.

Ah, but the self-confidence and conceit of youth! Pompey, still some months short of his twenty-seventh birthday, breezed off to see Sulla with no misgivings whatsoever.

“And how’s married life?” asked the Dictator blandly.

Pompey beamed. “Wonderful! Glorious! What a wife you found for me, Lucius Cornelius! Beautiful—educated—sweet. She’s pregnant. Due to drop my first son later this year.”

“A son, eh? Are you sure it will be a son, Magnus?”

“Positive.”

Sulla chuckled. “Well, you’re one of Fortune’s favorites, Magnus, so I suppose it will be a son. Gnaeus Junior … The Butcher, Kid Butcher, and Baby Butcher.”

“I like that!” exclaimed Pompey, not at all offended.

“You’re establishing a tradition,” said Sulla gravely.

“We certainly are! Three generations!”

Pompey sat back, pleased. Then, noted the watching Sulla, a different look came into the wide blue eyes; the happiness fled, replaced by a wary and thoughtful calculation as Pompey turned something over in his mind. Sulla waited without speaking until it came out.

“Lucius Cornelius…”

“Yes?”

“That law you promulgated—the one about making the Senate look outside of its own ranks if no military commander could be found among the senators …”

“The special commission, you mean?”

“That’s the one.”

“What about it?”

“Would it apply to me?”

“It could do.”

“But only if no one within the Senate volunteered.”

“It doesn’t quite say that, Magnus. It says if no capable and experienced commander within the Senate volunteers.”

“And who—decides that?”

“The Senate.”

Another silence fell. Then Pompey said, idly it seemed, “It would be nice to have lots of clients within the Senate.”

“It is always nice to have those, Magnus.”

At which point Pompey transparently decided to change the subject. “Who will be the consuls for next year?” he asked.

“Catulus, for one. Though I haven’t decided yet whether he’s to be senior or junior consul. A year ago, it seemed a clear—cut decision. Now I’m not so sure.”

“Catulus is like Metellus Pius—a stickler.”

“Perhaps. Neither as old nor as wise, unfortunately.”

“Do you think Metellus Pius can beat Sertorius?”

“At first, probably not,” said Sulla, smiling. “However, don’t hold my Piglet too lightly, Magnus. It takes him a while to get into stride. But once he finds his stride he’s very good.”

“Pah! He’s an old woman!” said Pompey contemptuously.

“I’ve known some doughty old women in my time, Magnus.”

Back to the changed subject: “Who else will be consul?’’

“Lepidus.”

“Lepidus?” Pompey gaped.

“Don’t you approve?”

“I didn’t say I didn’t approve, Lucius Cornelius. As a matter of fact, I think I do! I just didn’t think your mind was inclined his way. He hasn’t been obsequious enough.”

“Is that what you believe? That I give the big jobs only to men willing to wash my arse?”

Give Pompey his due, he was never afraid. So, much to Sulla’s secret amusement, he continued. “Not really. But you certainly haven’t given the big jobs to men who have made it as obvious as Lepidus has that he doesn’t approve of you.”

“Why should I?” asked Sulla, looking amazed. “I’m not fool enough to give the big jobs to men who might undermine me!”

“Then why Lepidus?”

“I’m due to retire before he takes office. And Lepidus,” said Sulla deliberately, “is aiming high. It has occurred to me that it might be better to make him consul while I’m still alive.”

“He’s a good man.”

“Because he questioned me publicly? Or despite that?”

But “He’s a good man” was as far as Pompey was prepared to go. In truth, though he found the appointment of Lepidus not in character for Sulla, he was only mildly interested. Of far more interest was Sulla’s provision for the special commission. When he had heard of it he had wondered what he himself might have had to do with it, but it had been no part of Pompey’s plans at that stage to ask Sulla. Now, almost two years since the law had been passed, he thought it expedient to enquire rather than ask. The Dictator was right, of course. A man found it hard enough to gain his objectives as a member of the Senate; but seeking his objectives from that body when a man was not a member of it would prove extremely difficult indeed.

Thus after Pompey took his leave of Sulla and commenced the walk home, he strolled along deep in thought. First of all, he would have to establish a faction within the Senate. And after that he would have to create a smaller group of men willing—for a price, naturally—to intrigue actively and perpetually on his behalf, even engage in underhand activities. Only—where to begin?

Halfway down the Kingmakers’ Stairs, Pompey halted, turned, took them lithely two at a time back up onto the Clivus Victoriae, no mean feat in a toga. Philippus! He would begin with Philippus.

Lucius Marcius Philippus had come a long way since the day he had paid a visit to the seaside villa of Gaius Marius and told that formidable man that he, Philippus, had just been elected a tribune of the plebs, and what might he do for Gaius Marius?—for a price, naturally. How many times inside his mind Philippus had turned his toga inside out and then back again, only Philippus knew for certain. What other men knew for certain was that he had always managed to survive, and even to enhance his reputation. At the time Pompey went to see him, he was both consular and ex-censor, and one of the Senate’s elders. Many men loathed him, few genuinely liked him, but he was a power nonetheless; somehow he had succeeded in persuading most of his world that he was a man of note as well as clout.

He found his interview with Pompey both amusing and thought—provoking, never until now having had much to do with Sulla’s pet, but well aware that in Pompey, Rome had spawned a young man who deserved watching. Philippus was, besides, financially strapped again. Oh, not the way he used to be! Sulla’s proscriptions had proven an extremely fruitful source of property, and he had picked up several millions’ worth of estates for several thousands. But, like a lot of men of his kind, Philippus was not a handy manager; money seemed to slip away faster than he could gather it in, and he lacked the ability to supervise his rural money—making enterprises—as well as the ability to choose reliable staff.

“In short, Gnaeus Pompeius, I am the opposite of men like Marcus Licinius Crassus, who still has his first sestertius and now adds them up in millions upon millions. His people tremble in their shoes whenever they set eyes on him. Mine smile slyly.”

“You need a Chrysogonus,” said the young man with the wide blue gaze and the frank, open, attractive face.

Always inclined to run to fat, Philippus had grown even softer and more corpulent with the years, and his brown eyes were almost buried between swollen upper lids and pouched lower ones. These eyes now rested upon his youthful adviser with startled and wary surprise: Philippus was not used to being patronized.

“Chrysogonus ended up impaled on the needles below the Tarpeian Rock!”

“Chrysogonus had been extremely valuable to Sulla in spite of his fate,” said Pompey. “He died because he had enriched himself from the proscriptions—not because he enriched himself by stealing directly from his patron. Over the many years he worked for Sulla, he worked indefatigably. Believe me, Lucius Marcius, you do need a Chrysogonus.”

“Well, if I do, I have no idea how to find one.”

“I’ll undertake to find one for you if you like.”

The buried eyes now popped out of their surrounding flesh. “Oh? And why would you be willing to do that, Gnaeus Pompeius?”

“Call me Magnus,” said Pompey impatiently.

“Magnus.”

“Because I need your services, Lucius Marcius.”

“Call me Philippus.”

“Philippus.”

“How can I possibly serve you, Magnus? You’re rich beyond most rich men’s dreams—even Crassus’s, I’d venture! You’re—what?—in your middle twenties somewhere?—and already famous as a military commander, not to mention standing high in Sulla’s favor—and that is hard to achieve. I’ve tried, but I never have.”

“Sulla is going,” said Pompey deliberately, “and when he goes I’ll sink back into obscurity. Especially if men like Catulus and the Dolabellae have anything to do with it. I’m not a member of the Senate. Nor do I intend to be.”

“Curious, that,” said Philippus thoughtfully. “You had the opportunity. Sulla put your name at the top of his first list. But you spurned it.”

“I have my reasons.”

“I imagine you do!”

Pompey got up from his chair and strolled across to the open window at the back of Philippus’s study, which, because of the peculiar layout of Philippus’s house (perched as it was near the bend in the Clivus Victoriae) looked not onto a peristyle garden but out across the lower Forum Romanum to the cliff of the Capitol. And there above the pillared arcade in which dwelt the magnificent effigies of the Twelve Gods, Pompey could see the beginnings of a huge building project; Sulla’s Tabularium, a gigantic records house in which would repose all of Rome’s accounts and law tablets. Other men, thought Pompey contemptuously, might build a basilica or a temple or a porticus, but Sulla builds a monument to Rome’s bureaucracy! He has no wings on his imagination. That is his weakness, his patrician practicality.

“I would be grateful if you could find a Chrysogonus for me, Magnus,” said Philippus to break the long silence. “The only trouble is that I am not a Sulla! Therefore I very much doubt that I would succeed in controlling such a man.”

“You’re not soft in anything except appearance, Philip—pus,” said the Master of Tact. “If I find you just the right man, you will control him. You just can’t pick staff, that’s all.”

“And why should you do this for me, Magnus?”

“Oh, that’s not all I intend to do for you!” said Pompey, turning from the window with a smile all over his face.

“Really?”

“I take it that your chief problem is maintaining a decent cash flow. You have a great deal of property, as well as several schools for gladiators. But nothing is managed efficiently, and therefore you do not enjoy the income you ought. A Chrysogonus will go far toward fixing that! However, it’s very likely that—as you’re a man of famously expensive habits—even an expanded income from all your estates and schools will not always prove adequate for your needs.”

“Admirably stated!” said Philippus, who was enjoying this interview, he now discovered, enormously.

“I’d be willing to augment your income with the gift of a million sesterces a year,” said Pompey coolly.

Philippus couldn’t help it. He gasped. “A million?”

“Provided you earn it, yes.”

“And what would I have to do to earn it?’’

“Establish a Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus faction within the Senate of sufficient power to get me whatever I want whenever I want it.” Pompey, who never suffered from bashfulness or guilt or any kind of self-deprecation, had no difficulty in meeting Philippus’s gaze when he said this.

“Why not join the Senate and do it for yourself? Cheaper!”

“I refuse to belong to the Senate, so that’s not possible. Besides which, I’d still have to do it. Much better then to do it behind the scenes. I won’t be sitting there to remind the senators that I might have any interest in what’s going on beyond the interest of a genuine Roman patriot—knight.”

“Oh, you’re deep!” Philippus exclaimed appreciatively. “I wonder does Sulla know all the sides to you?”

“Well, I’m why, I believe, he incorporated the special commission into his laws about commands and governorships.”

“You believe he invented the special commission because you refused to belong to the Senate?”

“I do.”

“And that is why you want to pay me fatly to establish a faction for you within the Senate. Which is all very well. But to build a faction will cost you far more money than what you pay me, Magnus. For I do not intend to disburse sums to other men out of my own money—and what you pay me is my own money.”

“Fair enough,” said Pompey equably.

“There are plenty of needy senators among the pedarii. They won’t cost you much, since all you need them for is a vote. But it will be necessary to buy some of the silver—tongues on the front benches too, not to mention a few more in the middle.” Philippus looked thoughtful. “Gaius Scribonius Curio is relatively poor. So is the adopted Cornelius Lentulus—Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus. They both itch for the consulship, but neither has the income to attain it. There are a number of Lentuli, but Lentulus Clodianus is the senior of the branch. He controls the votes of those backbenchers in the Lentulus clientele. Curio is a power within himself—an interesting man. But to buy them will take a considerable amount of money. Probably a million each. If Curio will sell himself. I believe he will for enough, but not blindly, and not completely. Lucius Gellius Poplicola would sell his wife, his parents and his children for a million, however.”

“I’d rather,” said Pompey, “pay them an annual income, as I will you. A million now might buy them, yes, but I think they would be happier if they knew that there was a regular quarter million coming in every year. In four years, that’s the million. But I am going to need them for longer than four years.”

“You’re generous, Magnus. Some might say foolishly so.”

“I am never foolish!” snapped Pompey. “I will expect to see a return for my money in keeping with the amount of it!”

For some time they discussed the logistics of payments and the amounts necessary to people the back benches with willing—nay, eager!—Pompeian voters. But then Philippus sat back with a frown, and fell silent.

“What is it?” asked Pompey a little anxiously.

“There’s one man you can’t do without. The trouble is he’s already got more money than he knows what to do with. So he can’t be bought and he makes great capital out of that fact.”

“You mean Cethegus.”

“I do indeed.”

“How can I get him?”

“I haven’t the faintest idea.”

Pompey rose, looking brisk. “Then I’d better see him.”

“No!” cried Philippus, alarmed. “Cethegus is a patrician Cornelian, and such a smooth and syrupy sort of man that you’d make an enemy out of him—he can’t deal with the direct approach. Leave him to me. I’ll sound him out, find what he wants.”

Two days later, Pompey received a note from Philippus. It contained only one sentence: “Get him Praecia, and he’s yours.”

Pompey held the note within the flame of a lamp until it kindled, shaking with anger. Yes, that was Cethegus! His payment was his future patron’s humiliation! He required that Pompey should become his pimp.

*

Pompey’s approach to Mucia Tertia was very different from his tactics in dealing with Aemilia Scaura—or Antistia, for that matter. This third wife was infinitely above numbers one and two. First of all, she had a mind. Secondly, she was enigmatic; he could never work out what she was thinking. Thirdly, she was quite wonderful in bed—what a surprise! Luckily he hadn’t made a fool of himself at the outset by calling her his wee pudding or his delectable honeypot; such terms had actually teetered on the tip of his tongue, but something in her face had killed them before he articulated them. Little though he had liked Young Marius, she had been Young Marius’s wife, and that had to count for much. And she was Scaevola’s daughter, Crassus Orator’s niece. Six years of living with Julia had to count for something too. So all Pompey’s instincts said Mucia Tertia must be treated more like an equal, and not at all like a chattel.

Therefore when he sought Mucia Tertia out, he did as he always did; gave her a lingering tongue—seeking kiss accompanied by a light and appreciative fondling of one nipple. Then—going away to sit where he could see her face, a smile of enslaved love and devotion. And after that—straight to the subject.

“Did you know I used to have a mistress in Rome?” he asked.

“Which one?” was her answer, solemn and matter—of—fact; she rarely smiled, Mucia Tertia.

“So you know of them all,” he said comfortably.

“Only of the two most notorious. Flora and Praecia.”

Clearly Pompey had forgotten Flora ever existed; he looked perfectly blank for several moments, then laughed and held his hands out. “Flora? Oh, she was forever ago!”

“Praecia,” said Mucia Tertia in a level voice, “was my first husband’s mistress too.”

“Yes, I knew that.”

“Before or after you approached her?”

“Before.”

“You didn’t mind?”

He could be quick, as he was now: “If I haven’t minded his widow, why should I mind his ex-mistress?”

“True.” She drew several skeins of finest woolen thread further into the light, and inspected them carefully. Her work, a piece of embroidery, lay in her swelling lap. Finally she chose the palest of the various purplish shades, broke off a length, and after sucking it to moisten it and rolling it between her fingers, held it up to ease it through the large eye of a needle. Only when the chore was done did she return her attention to Pompey. “What is it you have to say about Praecia?”

“I’m establishing a faction in the Senate.”

“Wise.” The needle was poked through the coarse fabric on which a complicated pattern of colored wools was growing, from wrong side to right side, then back again; the junction, when it was finished, would be impossible to detect. “Who have you begun with, Magnus? Philippus?”

“Absolutely correct! You really are wonderful, Mucia!”

“Just experienced,” she said. “I grew up surrounded by talk of politics.”

“Philippus has undertaken to give me that faction,” Pompey went on, “but there’s one person he couldn’t buy.”

“Cethegus,” she said, beginning now to fill in the body of a curlique already outlined with deeper purple.

“Correct again. Cethegus.”

“He’s necessary.”

“So Philippus assures me.”

“And what is Cethegus’s price?”

“Praecia.”

“Oh, I see.” The curlique was filling in at a great rate. “So Philippus has given you the job of acquiring Praecia for the King of the Backbenchers?”

“It seems so.” Pompey shrugged. “She must speak well of me, otherwise I imagine he’d have given the job to someone else.”

“Better of you than of Gaius Marius Junior.”

“Really?” Pompey’s face lit up. “Oh, that’s good!”

Down went work and needle; the deep green eyes, so far apart and doelike, regarded their lord and master inscrutably. “Do you still visit her, Magnus?”

“No, of course not!” said Pompey indignantly. His small spurt of temper died, he looked at her uncertainly. “Would you have minded if I had said yes?”

“No, of course not.” The needle went to work again.

His face reddened. “You mean you wouldn’t be jealous?”

“No, of course not.”

“Then you don’t love me!” he cried, jumping to his feet and walking hastily about the room.

“Sit down, Magnus, do.”

“You don’t love me!” he cried a second time.

She sighed, abandoned her embroidery. “Sit down, Gnaeus Pompeius, do! Of course I love you.”

“If you did you’d be jealous!” he snapped, and flung himself back into his chair.

“I am not a jealous person. Either one is, or one is not. And why should you want me to be jealous?’’

“It would tell me that you loved me.”

“No, it would only tell you that I am a jealous person,” she said with magnificent logic. “You must remember that I grew up in a very troubled household. My father loved my mother madly, and she loved him too. But he was always jealous of her. She resented it. Eventually his moods drove her into the arms of Metellus Nepos, who is not a jealous person. So she’s happy.”

“Are you warning me not to become jealous of you?”

“Not at all,” she said placidly. “I am not my mother.”

“Do you love me?”

“Yes, very much.”

“Did you love Young Marius?’’

“No, never.” The pale purple thread was all used up; a new one was broken off. “Gaius Marius Junior was not uxorious. You are, delightfully so. Uxoriousness is a quality worthy of love.”

That pleased him enough to return to the original subject. “The thing is, Mucia, how do I go about something like this? I am a procurer—oh, why dress it up in a fancy name? I am a pimp!”

She chuckled. Wonder of wonders, she chuckled! “I quite see how difficult a position it puts you in, Magnus.”

“What ought I to do?”

“As is your nature. Take hold of it and do it. You only lose control of events when you stop to think or worry how you’ll look. So don’t stop to think—and stop worrying about how you’ll look. Otherwise you’ll make a mess of it.”

“Just go and see her and ask her.”

“Exactly.” The needle was threaded again, her eyes lifted to his with another ghost of a smile in them. “However, there is a price for this advice, my dear Magnus.”

“Is there?”

“Certainly. I want a full account of how your meeting with Praecia goes.”

*

The timing of this negotiation, it turned out, was exactly right. No longer possessed of either Young Marius or Pompey, Praecia had fallen into a doldrums wherein both stimulus and interest were utterly lacking. Comfortably off and determined to retain her independence, she was now far too old to be a creature of driving physical passions. As was true of so many of her less well-known confederates in the art of love, Praecia had become an expert in sham. She was also an astute judge of character and highly intelligent. Thus she went into every sexual encounter from a superior position of power, sure of her capacity to please, and sure of her quarry. What she loved was the meddling in the affairs of men that normally had little or nothing to do with women. And what she loved most was political meddling. It was balm to intellect and disposition.

When Pompey’s arrival was announced to her, she didn’t make the mistake of automatically assuming he had come to renew his liaison with her, though of course it crossed her mind because she had heard that his wife was pregnant.

“My dear, dear Magnus!” she said with immense affability when he entered her study, and held out her hands to him.

He bestowed a light kiss on each before retreating to a chair some feet away from where she reclined on a couch, heaving a sigh of pleasure so artificial that Praecia smiled.

“Well, Magnus?” she asked.

“Well, Praecia!” he said. “Everything as perfect as ever, I see—has anyone ever found you and your surroundings less than perfect? Even if the call is unexpected?’’

Praecia’s tablinum —she gave it the same name a man would have—was a ravishing production in eggshell blue, cream, and precisely the right amount of gilt. As for herself—she rose every day of her life to a toilet as thorough as it was protracted, and she emerged from it a finished work of art.

Today she wore a quantity of tissue—fine draperies in a soft sage—green, and had done up her pale gold hair like Diana the Huntress, in disciplined piles with straying tendrils which looked absolutely natural rather than the result of much tweaking with the aid of a mirror. The beautiful cool planes of her face were not obviously painted; Praecia was far too clever to be crude when Fortune had been so kind, even though she was now forty.

“How have you been keeping?” Pompey asked.

“In good health, if not in good temper.”

“Why not good temper?”

She shrugged, pouted. “What is there to mollify it? You don’t come anymore! Nor does anyone else interesting.”

“I’m married again.”

“To a very strange woman.”

“Mucia, strange? Yes, I suppose she is. But I like her.”

“You would.”

He searched for a way into saying what he had to say, but could find no trigger and thus sat in silence, with Praecia gazing at him mockingly from her half—sitting, half—lying pose. Her eyes—which were held to be her best feature, being very large and rather blindly blue—positively danced with this derision.

“I’m tired of this!” Pompey said suddenly. “I’m an emissary, Praecia. Not here on my own behalf, but on someone else’s.”

“How intriguing!”

“You have an admirer.”

“I have many admirers.”

“Not like this one.”

“And what makes him so different? Not to mention how he managed to send you to procure my services!’’

Pompey reddened. “I’m caught in the middle, and I hate it! But I need him and he doesn’t need me. So I’m here on his behalf.”

“You’ve already said that.”

“Take the barb out of your tongue, woman! I’m suffering enough. He’s Cethegus.”

“Cethegus! Well, well!” said Praecia purringly.

“He’s very rich, very spoiled, and very nasty,” said

Pompey. “He could have done his own dirty work, but it amuses him to make me do it for him.”

“It’s his price,” she said, “to make you act as his pimp.”

“It is indeed.”

“You must want him very badly.”

“Just give me an answer! Yes or no?”

“Are you done with me, Magnus?”

“Yes.”

“Then my answer to Cethegus is yes.”

Pompey rose to his feet. “I thought you’d say no.”

“In other circumstances I would have loved to say no, but the truth is that I’m bored, Magnus. Cethegus is a power in the Senate, and I enjoy being associated with men of power. Besides, I see a new kind of power in it for me. I shall arrange it so that those who seek favors from Cethegus will have to do so through cultivating me. Very nice!”

“Grr!” said Pompey, and departed.

He didn’t trust himself to see Cethegus; so he saw Lucius Marcius Philippus instead.

“Praecia is willing,” he said curtly.

“Excellent, Magnus! But why look so unhappy?”

“He made me pimp for him.”

“Oh, I’m sure it wasn’t personal!”

“Not much it wasn’t!”

*

In the spring of that year Nola fell. For almost twelve years that Campanian city of Samnite persuasion had held out against Rome and Sulla, enduring one siege after another, mostly at the hands of this year’s junior consul, Appius Claudius Pulcher. So it was logical that Sulla ordered Appius Claudius south to accept Nola’s submission, and logical too that Appius Claudius took great pleasure in telling the city’s magistrates the details of Sulla’s unusually harsh conditions. Like Capua, Faesulae and Volaterrae, Nola was to keep no territory whatsoever; it all went to swell the Roman ager publicus. Nor were the men of Nola to be given the Roman citizenship. The Dictator’s nephew, Publius Sulla, was given authority in the area, an added gall in view of last year’s mission to sort out the tangled affairs of Pompeii, where Publius Sulla’s brand of curt insensitivity had only ended in making a bad situation worse.

But to Sulla the submission of Nola was a sign. He could depart with his luck intact when the place where he had won his Grass Crown was no more. So the months of May and June saw a steady trickle of his possessions wending their way to Misenum, and a team of builders toiled to complete certain commissions at his villa there—a small theater, a delightful park complete with sylvan dells, waterfalls and many fountains, a huge deep pool, and several additional rooms apparently designed for parties and banquets. Not to mention six guest suites of such opulence that all Misenum was talking: who could Sulla be thinking of entertaining, the King of the Parthians?

Then came Quinctilis, and the last in the series of Sulla’s mock elections. To Catulus’s chagrin, he was to be the junior consul; the senior was Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, a name no one had expected to hear in the light of his independent line in the Senate since Sulla had assumed the Dictatorship.

At the beginning of the month Valeria Messala and the twins left for the Campanian countryside; everything at the villa was ready. In Rome, no one anticipated surprises. Sulla would go—as he had come and as he had prevailed—in an aura of dense respectability and ceremony. Rome was about to lose her first dictator in a hundred and twenty years, and her first—ever dictator who had held the office for longer than six months.

The ludi Apollinares, games first staged by Sulla’s remote ancestor, came and went; so did the elections. And the day after the curule elections a huge crowd gathered in the lower Forum Romanum to witness Sulla’s laying down of his self-inflicted task. He was going to do this in public rather than within the Curia Hostilia of the Senate—from the rostra, an hour after dawn.

He did it with dignity and an impressive majesty, first dismissing his twenty-four lictors with extreme courtesy and (for Sulla) costly gifts, then addressing the crowds from the rostra before going with the electors to the Campus Martius, where he oversaw the repeal of Flaccus Princeps Senatus’s law appointing him Dictator. He went home from the Centuriate Assembly a private citizen, shorn of imperium and official auctoritas.

“But I should like some of you to see me leave Rome,” he said to the consuls Vatia and Appius Claudius, to Catulus, Lepidus, Cethegus, Philippus. “Be at the Porta Capena an hour after dawn tomorrow. Nowhere else, mind! Watch me say goodbye to Rome.”

They obeyed him to the letter, of course; Sulla might now be a privatus stripped of all magisterial power, but he had been the Dictator for far too long for any man to believe he truly lacked power. Sulla would be dangerous as long as he lived.

Everyone bidden to the Porta Capena therefore came, though the three most favored Sullan protégés—Lucullus, Mamercus and Pompey—were not in Rome. Lucullus was on business for his games in September and Mamercus was in Cumae, while Pompey had gone back to Picenum to await the birth of his first child. When Pompey later heard of the events at the Capena Gate, he was profoundly thankful for his absence; Lucullus and Mamercus felt exactly the opposite.

The marketplace inside the gate was jammed with busy folk going about their various activities—selling, buying, peddling, teaching, strolling, flirting, eating. Of course the party in uniformly purple-bordered togas was eyed with great interest; the usual volley of loud, anti—upper—class, derogatory insults was thrown from every direction, but the curule senators had heard it all before, and took absolutely no notice. Positioning themselves close to the imposing arch of the gate, they waited, talking idly.

Not long afterward came the strains of music—pipes, little drums, tuneful flutes, outlining and filling in an unmistakably Bacchic lay. A flutter ran through the marketplace throng, which separated, stunned, to permit the progress of the procession now appearing from the direction of the Palatine. First came flower—decked harlots in flame—colored togas, thumping their wrists against jingling tambourines, dipping their hands into the swollen sinuses of their togas to strew the route with drifts of rose petals. Then came freaks and dwarves, faces pugged or painted, some in horn—bedecked masks sewn with bells, capering on malformed legs and clad in the motley of centunculi, vividly patched coats like fragmented rainbows. After them came the musicians, some wearing little more than flowers, others tricked out like prancing satyrs or fanciful eunuchs. In their midst, hedged about by giggling, dancing children, staggered a fat and drunken donkey with its hooves gilded, a garland of roses about its neck and its mournful ears poking out of holes in a wide—brimmed, wreathed hat. On its purple-blanketed back sat the equally drunken Sulla, waving a golden goblet which slopped an endless rain of wine, robed in a Tyrian purple tunic embroidered with gold, flowers around his neck and atop his head. Beside the donkey walked a very beautiful but obviously male woman, his thick black hair just sprinkled with white, his unfeminine physique draped in a semi—transparent saffron woman’s gown; he bore a large golden flagon, and every time the goblet in Sulla’s right hand descended in his direction he topped up its splashing purple contents.

Since the slope toward the gate was downward the procession gained a certain momentum it could not brake, so when the archway loomed immediately before it and Sulla started shouting blearily for a halt, everyone fell over squealing and shrieking, the women’s legs kicking in the air and their hairy, red-slashed pudenda on full display. The donkey staggered and cannoned into the wall of a fountain; Sulla teetered but was held up by the travestied flagon—bearer alongside him, then toppled slowly into those strong arms. Righted, the Dictator commenced to walk toward the stupefied party of curule senators, though as he passed by one wildly flailing pair of quite lovely female legs, he bent to puddle his finger inside her cunnus, much to her hilarious and apparently orgasmic delight.

As the escort regained its feet and clustered, singing and playing music and dancing still—to the great joy of the gathering crowd—Sulla arrived in front of the consuls to stand with his arm about his beautiful supporter, waving the cup of wine in an expansive salute.

“Tacete!” yelled Sulla to the dancers and musicians. They quietened at once. But no other voices filled the silence.

“Well, it’s here at last!” he cried—to whom, no one could be sure: perhaps to the sky. “My first day of freedom!”

The golden goblet described circles in the air as the richly painted mouth bared its gums in the broadest and happiest of smiles. His whole face beneath the absurd ginger wig was painted as white as the patches of intact skin upon it, so that the livid areas of scar tissue were gone. But the effect was not what perhaps he had hoped, as the red outline of his mouth had run up into the many deep fissures starting under nose and on chin and foregathering at the lips; it looked like a red gash sewn loosely together with wide red stitches. But it smiled, smiled, smiled. Sulla was drunk, and he didn’t care.

“For thirty years and more,” he said to the slack—featured Vatia and Appius Claudius, “I have denied my nature. I have denied myself love and pleasure—at first for the sake of my name and my ambition, and later—when these had run their course—for the sake of Rome. But it is over. Over, over, over! I hereby give Rome back to you—to all you little, cocksure, maggot—minded men! You are at liberty once more to vent your spleen on your poor country—to elect the wrong men, to spend the public moneys foolishly, to think not beyond tomorrow and your own gigantic selves. In the thirty years of one generation I predict that you and those who succeed you will bring ruin beyond redemption upon Rome’s undeserving head!”

His hand went up to touch the face of his supporter, very tenderly and intimately. “You know who this is, of course, any of you who go to the theater. Metrobius. My boy. Always and forever my boy!” And he turned, pulled the dark head down, kissed Metrobius full upon the mouth.

Then with a hiccough and a giggle he allowed himself to be helped back to his drunken ass, and hoisted upon it. The tawdry procession re-formed and weaved off through the gate down the common line of the Via Latina and the Via Appia, with half the people from the marketplace following and cheering.