The death of Sulla had marked the end of amicable relations between the consuls Lepidus and Catulus. Not a pair who by nature were intended to get on together, the actual passing of the Dictator saw the first instance of their falling out; Catulus proposed that Sulla be given a State funeral, whereas Lepidus refused to countenance the expenditure of public funds to bury one whose estate could well afford to bear this cost. It was Catulus who won the ensuing battle in the Senate; Sulla was interred at the expense of the Treasury he had, after all, been the one to succeed in filling.

But Lepidus was not without support, and Rome was starting to see those return whom Sulla had forced to flee. Marcus Perperna Veiento and Cinna’s son, Lucius, were both in Rome shortly after the funeral was over. Somehow Perperna Veiento had succeeded in evading actual proscription despite his tenure of Sicily at the advent of Pompey—probably because he had not stayed to contest possession of Sicily with Pompey, and had not enough money to make him an alluring proscription prospect. Young Cinna, of course, was penniless. But now that the Dictator was dead both men formed the nucleus of factions secretly opposed to the Dictator’s policies and laws, and naturally preferred to side with Lepidus rather than with Catulus.

Not only the senior consul but also armed with a reputation of having stood up to Sulla in the Senate, Lepidus considered himself in an excellent position to lessen the stringency of some of Sulla’s legislation now that the Dictator was dead, for his senatorial supporters actually outnumbered those who were for Catulus.

“I want,” said Lepidus to his great friend Marcus Junius Brutus, “to go down in the history books as the man who regulated Sulla’s laws into a form more acceptable to everyone—even to his enemies.”

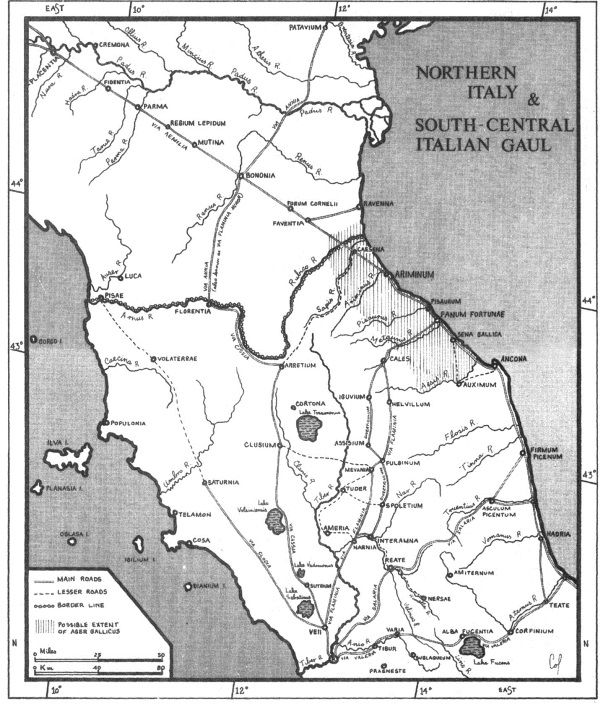

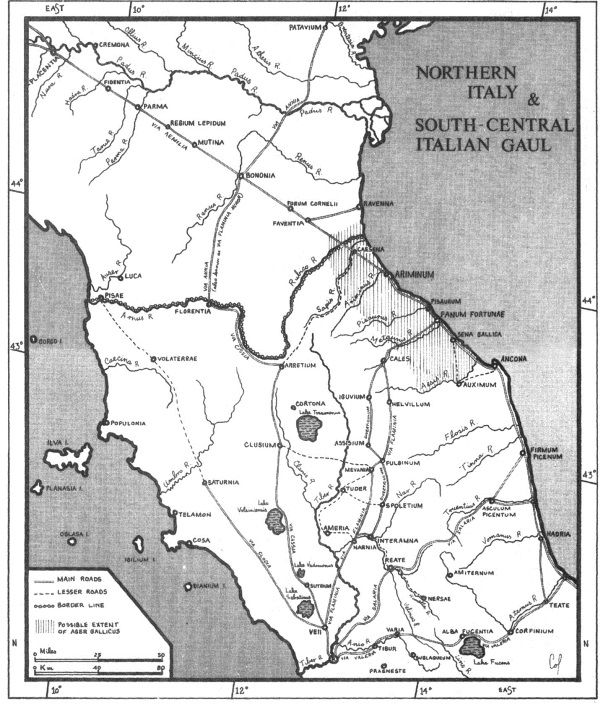

Fortune had favored both of them. Sulla’s last handpicked list of magistrates had included as a praetor the name of Brutus, and when the consuls and praetors had assumed office on the previous New Year’s Day, the lots to determine which provinces would go to which executives had been good to both Lepidus and Brutus; Lepidus had drawn Gaul-across-the-Alps and Brutus Italian Gaul, their terms as governors to commence at the end of their terms in office—that is, on the next New Year’s Day. Gaul-across-the-Alps had not recently been a consul’s province, but two things had changed that: the war in Spain against Quintus Sertorius (not going well) and the state of the Gallic tribes, now stirring into revolt and thus threatening the land route to Spain.

“We’ll be able to work our provinces as a team,” Lepidus had said eagerly to Brutus once the lots were drawn. “I’ll wage war against rebellious tribes while you organize Italian Gaul to send me supplies and whatever other support I might need.”

Thus both Lepidus and Brutus looked forward to a busy and rewarding time as governors next year. Once Sulla was buried, Lepidus had gone ahead with his program to soften the harshest of Sulla’s laws, while Brutus, president of the Violence court, coped with the amendments to Sulla’s laws for that court instituted in the previous year by Sulla’s praetor Gnaeus Octavius. Apparently with Sulla’s consent, Gnaeus Octavius had legislated to compel some of the proscription profiteers to give back property obtained by violence, force, or intimidation—which of course also meant removing the names of the original owners from the lists of the proscribed. Approving of Gnaeus Octavius’s measure, Brutus had continued his work with enthusiasm.

In June, Sulla’s ashes now enclosed in the tomb on the Campus Martius, Lepidus announced to the House that he would seek the House’s consent to a lex Aemilia Lepida giving back some of the land Sulla had sequestrated from towns in Etruria and Umbria in order to bestow it upon his veterans.

“As you are all aware, Conscript Fathers,” Lepidus said to an attentive Senate, “there is considerable unrest to the north of Rome. It is my opinion—and the opinions of many others!—that most of this unrest stems out of our late lamented Dictator’s fixation upon punishing the communities of Etruria and Umbria by stripping from them almost every last iugerum of town land. That the House was not always in favor of the Dictator’s measures, the House clearly showed when it opposed the Dictator’s wish to proscribe every citizen in the towns of Arretium and Volaterrae. And it is to our credit that we did manage to dissuade the Dictator from doing this, even though the incident occurred when he was at the height of his power. Well, do not think that my new law has anything good to offer Arretium and Volaterrae! They actively supported Carbo, which means they will get nothing from me. No, the communities I am concerned about were at most involuntary hosts to Carbo’s legions. I speak about places like Spoletium and Clusium, at the moment seething with resentment against Rome because they have lost their town lands, yet were never traitorous! Just the hapless victims of civil war, in the path of someone’s army.”

Lepidus paused to look along the tiers on both sides of the Curia Hostilia, and was satisfied at what his eyes saw. A little more feeling in his voice, he continued.

“Any place which actively supported Carbo is not at issue here, and the lands of these traitors are more than enough to settle Sulla’s soldiers upon. I must emphasize that. With very few exceptions, Italy is now Roman to the core, its citizens enfranchised and distributed across the full gamut of the thirty-five tribes. Yet many of the districts of Etruria and Umbria in particular are still being treated like rebellious old—style Allies, for during those times it was always Roman practice to confiscate a district’s public lands. But how can Rome usurp the lands of proper, legal Romans? It is a contradiction! And we, Conscript Fathers of Rome’s senior governing body, cannot continue to condone such practices. If we do, there will be yet another rebellion in Etruria and Umbria—and Rome cannot afford to wage another war at home when she is so pressed abroad! At the moment we have to find the money to support fourteen legions in the field against Quintus Sertorius. And obviously this is where our precious money must go. My law to give back their lands to places like Clusium and Tuder will calm the people of Etruria and Umbria before it is too late.”

The Senate listened, though Catulus spoke out strongly against the measure and was followed by the most pro—Sullan and conservative elements, as Lepidus had expected.

“This is the thin end of the wedge!” cried Catulus angrily. “Marcus Aemilius Lepidus intends to pull down our newly formed constitution a piece at a time by starting with measures he knows will appeal to this House! But I say it cannot be allowed to happen! Every measure he succeeds in having sent to the People with a senatus consultant attached will embolden him to go further!”

But when neither Cethegus nor Philippus came out in support of Catulus, Lepidus felt he was going to win. Odd perhaps that they had not supported Catulus; yet why question such a gift? He therefore went ahead with another measure in the House before he had succeeded in obtaining a senatus consultum of approval for his bill to give back the sequestrated lands.

“It is the duty of this House to remove our late lamented Dictator’s embargo upon the sale of public grain at a price below that levied by the private grain merchants,” he said firmly, and with the doors of the Curia Hostilia opened wide so that those who listened outside could hear. “Conscript Fathers, I am a sane, decent man! I am not a demagogue. As senior consul I have no need to woo our poorest citizens. My political career is at its zenith—I am not a man on the rise. I can afford to pay whatever the private grain merchants ask for their wheat. Nor do I mean to imply that our late lamented Dictator was wrong when he fixed the price of public grain to the price asked by the private grain merchants. I think our late lamented Dictator did not realize the consequences, is all. For what in actual fact has happened? The private grain merchants have raised their prices because there is now no governmental policy to oblige them to keep their prices down! After all, Conscript Fathers, what businessman can resist the prospect of greater profits? Do kindness and humanity dictate his actions? Of course not! He’s in business to make a profit for himself and his shareholders, and mostly he is too myopic to see that when he raises the price of his product beyond the capacity of his largest market to pay for it, he begins to erode his whole profit basis.

“I therefore ask you, members of this House, to give my lex Aemilia Lepida frumentaria your official stamp of approval, enabling me to put it before the People for ratification. I will go back to our old, tried—and—true method, which is to have the State offer public grain to the populace for the fixed price of ten sesterces the modius. In years of plenty that price still enables the State to make a good profit, and as years of plenty outnumber years of scarcity, in the long run the State cannot suffer financially.”

Again the junior consul Catulus spoke in opposition. But this time support for him was minimal; both Cethegus and Philippus were in unequivocal favor of Lepidus’s measure. It therefore got its senatus consultum at the same session as Lepidus brought it up. Lepidus was free to promulgate his law in the Popular Assembly, and did. His reputation rose to new heights, and when he appeared in public he was cheered.

But his lex agraria concerning the sequestrated lands was a different matter; it lingered in the House, and though he put it to the vote at every meeting, he continued to fail to secure enough votes to obtain a senatus consultum—which meant that under Sulla’s constitution he could not take it to an Assembly.

“But I am not giving up,” he said to Brutus over dinner at Brutus’s house.

He ate at Brutus’s house regularly, for in truth he found his own house unbearably empty these days. At the time the proscriptions had begun, he, like most of Rome’s upper classes, had very much feared he would be proscribed; he had remained in Rome during the years of Marius, Cinna and Carbo—and he was married to the daughter of Saturninus, who had once attempted to make himself King of Rome. It had been Appuleia herself who had suggested that he divorce her at once. They had three sons, and it was of paramount importance that the family fortunes remain intact for the younger two of these boys; the oldest had been adopted into the ranks of Cornelius Scipio and was bound to prosper, that family being closely related to Sulla and uniformly in Sulla’s camp. Scipio Aemilianus (namesake of his famous ancestor) was fully grown at the time Appuleia suggested the divorce, and the second son, Lucius, was eighteen. The youngest, Marcus, was only nine. Though he loved Appuleia dearly, Lepidus had divorced her for the sake of their sons, thinking that at some time in the future when it was safe, he would remarry her. But Appuleia was not the daughter of Saturninus for nothing; convinced that her presence in the lives of her ex-husband and her sons would always place them in jeopardy, she committed suicide. Her death was a colossal blow to Lepidus, who never really recovered emotionally. And so whenever he could he spent his private hours in the house of another man: especially the house of his best friend, Brutus.

“Exactly right! You must never give up,” said Brutus. “A steady perseverance will wear the Senate down, I’m sure of it.”

“You had better hope that senatorial resistance crumbles quickly,” said the third diner, seated on a chair opposite the lectus medius.

Both men looked at Brutus’s wife, Servilia, with a concern tempered by considerable respect; what Servilia had to say was always worth hearing.

“What precisely do you mean?’’ asked Lepidus.

“I mean that Catulus is girding himself for war.”

“How did you find that out?” asked Brutus.

“By keeping my ears pricked,” she said with expressionless face. Then she smiled in her secretive, buttoned—up way. “I popped around to visit Hortensia this morning, and she’s not the sister of our greatest advocate for no reason—like him, she’s an inveterate talker. Catulus adores her, so he talks to her too much—and she talks to anyone with the skill to pump her.”

“And you, of course, have that skill,” said Lepidus.

“Certainly. But more importantly I have the interest to pump her. Most of her female visitors are more fascinated by gossip and women’s matters, whereas Hortensia would far rather talk politics. So I make it my business to see her often.”

“Tell us more, Servilia,” said Lepidus, not understanding what she was saying. “Catulus is girding himself for what war? Nearer Spain? He’s to go there as governor next year, complete with a new army. So I suppose it’s not illogical that he’s—er, girding himself for war, as you put it.”

“This war has nothing to do with Spain or Sertorius,” said Brutus’s wife. “Catulus is talking of war in Etruria. According to Hortensia, he’s going to start persuading the Senate to arm more legions to deal with the unrest there.”

Lepidus sat up straight on the lectus medius. ”But that’s insanity! There is only one way to keep the peace in Etruria, and that’s to give its communities back a good proportion of what Sulla took away from them!”

“Are you in touch with any of the local leaders in Etruria?” asked Servilia.

“Of course.”

“The diehards or the moderates?”

“The moderates, I suppose, if by diehards you mean the leaders of places like Volaterrae and Faesulae.”

“That’s what I mean.”

“I thank you for your information, Servilia. Rest assured, I will redouble my efforts to settle matters in Etruria.”

*

Lepidus did redouble his efforts, but could not prevent Catulus from exhorting the house to start recruiting the legions he believed would be necessary to put down the brewing revolt in Etruria. Servilia’s timely warning, however, enabled Lepidus to canvass support among the pedarii and the senior backbenchers like Cethegus; the House, listening to Catulus’s impassioned diatribe, was lukewarm.

“In fact, Quintus Lutatius,” said Cethegus to Catulus, “we are more concerned about the lack of amity between you and our senior consul than we are about hypothetical revolts in Etruria. It seems to us that you have adopted an inflexible policy of opposing whatever our senior consul wants. I find that sad, especially so soon after Lucius Cornelius Sulla went to so much trouble to forge new bonds of co-operation between the various members and factions within the Senate of Rome.”

Squashed, Catulus subsided. Not, as it turned out, for very long. Events conspired to make him seem right and to kill any chance Lepidus had of obtaining that elusive senatus consultum for his law giving back much of the sequestrated lands. For at the end of June the dispossessed citizens of Faesulae attacked the soldier settlements all around it, threw the veterans off their allotments, and killed those who resisted.

The deaths of several hundred loyal Sullan legionaries could not be ignored, nor could Faesulae be allowed to get away with outright rebellion. At a moment when the Senate should have been turning its attention toward preparing for the elections to be held in Quinctilis, the Senate forgot all about elections. The lots had been cast to determine which consul would conduct the curule balloting (they fell upon Lepidus), this being a new part of Sulla’s constitution, but nothing further was done. Instead, the House instructed both consuls to recruit four new legions each and proceed to Faesulae to put the insurrection down.

The meeting was preparing to break up when Lucius Marcius Philippus rose and asked to speak. Lepidus, who held the fasces for the month of Quinctilis, made his first major mistake: he decided to allow Philippus to have his say.

“My dear fellow senators,” said Philippus in stentorian tones, “I beg you not to put an army into the hands of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus! I do not request. I do not ask. I beg! For it is plain to me that our senior consul is plotting revolution—has been plotting revolution ever since he was inaugurated! Until our beloved Dictator died, he did and said nothing. But the moment our beloved Dictator died, it started. He refused to countenance the voting of State funds to bury Sulla! Of course he lost—but I for one never believed he thought he could win! He used the funeral debate as a signal to all his supporters that he was about to legislate treasonous policies. And he proceeded to legislate treasonous policies! He proposed to give back sequestrated lands to people who had deserved to lose them! And when this body stalled, he sought the adulation of every Class lower than the Second by a trick every demagogue has used, from Gaius Gracchus to Lepidus’s father-in-law Saturninus—he legislated cheap State grain! Rome was not supposed to vote money to honor the dead body of her greatest citizen—oh, no! But Rome was supposed to spend far more of her public money to dower her worthless proletarii with cheap grain—oh, yes!”

Lepidus was not the only man stunned by this attack; the whole House was sitting bolt upright in shock. Philippus swept on.

“Now, my fellow senators, you want to give this man four legions and send him off to Etruria? Well, I refuse to let you do that! For one thing, the curule elections are due to be held shortly and the lot fell upon him to hold them. Therefore he must remain in Rome to do his duty, not go haring off to raise an army! I remind you that we are about to hold our first free elections in some years, and that it is imperative we hold them on time and with due legality. Quintus Lutatius Catulus is perfectly capable of recruiting and waging war against Faesulae and any other Etrurian communities which may choose to side with Faesulae. It is against Sulla’s laws for both consuls to be absent from Rome in order to wage war. Indeed, it was to prevent that from happening that our beloved Dictator incorporated his clause about the specially commissioned command into his opus! We have been provided with the constitutional means to give command in our wars to the most competent man available, even if he is not a member of the Senate. Yet here I find you giving a vital command to a man who has no decent war record! Quintus Lutatius is tried and true, we know him to be competent in military matters. But Marcus Aemilius Lepidus? He’s unversed and unproven! He is also, I maintain, a potential revolutionary. You cannot give him legions and send him to wage war in an area where the words out of his own mouth have indicated a treasonous interest in favoring that area over Rome!”

Lepidus had listened slack—jawed to the opening sentences of this speech, but then with sudden decision had turned to his clerk and snatched the wax tablet and stylus from those hands; for the remainder of the time Philippus spoke he took notes. Now he rose to answer, the tablet held where he could refer to it.

“What is your motive in saying these things, Philippus?” he asked, not according Philippus the courtesy of his full name. “I confess myself at a loss to divine your motive—but you have one, of that I am sure! When the Great Tergiversator rises in this House to deliver one of his magnificently worded and delivered speeches, rest assured there is always a hidden motive! Some fellow is paying him to turn his toga yet again! How rich he has become!—how fat!—how contented!—how sunk in a private mire of voluptuousness!—and always in the pay of some creature who needs a senatorial mouthpiece!”

The wax tablet was lifted a little; Lepidus glared sternly across its top at the silent senators. Even Catulus, a glance in his direction showed, was flabbergasted by Philippus’s speech. Whoever was behind him, it was definitely not Catulus or any member of his faction.

“I will deal with Philippus’s points in order, Conscript Fathers. One, my passivity before the Dictator died. That is not true! As everyone here knows! Cast your minds back!

“Two, the voting of public funds to pay for the Dictator’s funeral. Yes, I was opposed. So were many other men. And why not? Are we to have no voices?

“As for—three—my opposition being a signal to my—do I have any?—supporters that I would undo everything Lucius Cornelius Sulla knitted up—what absolute rubbish! I have attempted to have two laws enacted and succeeded with one alone. But have I given the slightest indication to anybody that I intend to overturn Sulla’s entire body of laws? Have you heard me criticizing the new court system? Or the new regulations governing the public servants? The Senate? The election process? The new treason laws restraining the actions of provincial governors? The restricted functions of the Assemblies? Even the severely curtailed tribunate of the plebs? No, Conscript Fathers, you have not! Because I do not intend to tamper with these provisions!’’

The last sentence was thundered out, so much so that not a few of the men who listened jumped. He paused to allow everyone to recover, then pressed on.

“Four, the allegation that my law returning some sequestrated lands—some, not all!—to their original owners is a treasonous one. That too is rubbish. My lex Aemilia Lepida does not say that any confiscated lands belonging to genuinely treasonous towns or districts should be given back. It concerns only lands belonging to places whose participation in the war against Carbo was innocent or involuntary.”

Lepidus dropped his voice, put much feeling into it. “My fellow senators, stop to think for a moment, please! If we are to see a truly united and properly Roman Italy, we must cease to inflict the old penalties we imposed upon the Italian Allies upon men who under the law are now as Roman as we are ourselves! If Lucius Cornelius Sulla erred anywhere, it was in that. In a man of his age it was perhaps understandable. But it is unpardonable for the majority of us, at least twenty years his junior, to think along the same lines he did. I remind you that Philippus here is also an old man, with an old man’s outmoded prejudices. When he was censor he displayed his prejudices flagrantly by refusing to do what Sulla in actual fact did do—distribute the new Roman citizens right across the thirty-five tribes.”

He was beginning to sway them, for indeed this was a much younger body than it had been ten years ago. Feeling the worst of his anxiety lift, Lepidus continued.

“Five, my grain law. That too righted a very manifest wrong. I believe that had Lucius Cornelius Sulla stayed on as the Dictator for a longer period of time, he would have seen this for himself and done what I did—legislated to return cheap grain to the lower classes. The grain merchants were greedy. None can deny it! And indeed this body was wise enough to see the good sense behind my grain law, for you authorized its passage, and thus removed the likelihood that with this coming harvest Rome might have seen violence and riots. For you cannot take away from the common people a privilege that has been with them long enough for them to assume it is a right!

“Six, my function as the consul chosen by lot to supervise the curule elections. Yes, the lot did fall upon me, and under our new constitution that means I alone can officiate at the curule elections. But, Conscript Fathers, it was not I who asked to be directed to take four legions and put down the revolt at Faesulae as my first order of business! It was you directed me! Of your own free will! Unsolicited by me! It did not occur to you—nor did it occur to me!—that business of the nature of the curule elections should take precedence over open revolt within Italy. I confess that I assumed I was first to help put down open revolt, and only then hold the curule elections. There is plenty of time before the end of the year for elections. After all, it is only the beginning of Quinctilis.

“Seven, it is not expressly against the laws of Sulla that both consuls should be absent from Rome in order to wage war. Even to wage war outside Italy. According to Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the first duty of the consuls is to care for Rome and Italy. Neither Quintus Lutatius Catulus nor I will be exceeding his authority. The clause providing for the specially commissioned non—senatorial commander can only be brought into being if the legally elected magistrates and all other competent senators are not available to wage war.

“And finally, point number eight,” said Lepidus. “How am I less qualified to command in a war than Quintus Lutatius Catulus? Each of us last saw service during the Italian War, as legates. Neither of us left Rome during the years of Cinna and Carbo. Both of us maintained an honest and obdurate neutrality which Lucius Cornelius Sulla most definitely did not punish us for—after all, here we are, his last pair of personally chosen consuls! Our military experience is much of a muchness. There is nothing to say which of us may shine the brighter in the field against Faesulae. It is in Rome’s interests to hope that both of us shine with equal brightness, is it not?

Normal Roman practice says that if the consuls are willing to assume the mantle of military command at the directive of the Senate, then the consuls must do so. The consuls were so directed by the Senate. The consuls have done so. There is no more to be said.”

But Philippus was not done. Displaying neither frustration nor anger, smoothly and reasonably he turned the debate around into a lament against the obvious enmity which had flared between the consuls, and labored this point through what seemed like half a hundred concrete examples from mere asides to major clashes. The sun had set (which meant that technically the Senate had to end its deliberations), but both Catulus and Lepidus were unwilling to postpone a decision until the following day, so the clerks of the House kindled torches and Philippus droned on. It was very well done. By the time that Philippus reached his peroration, the senators would have agreed to practically anything to be allowed to go home for food and sleep.

“What I propose,” he said at last, “is that each of the consuls swears an oath to the effect that he will not turn his army into an instrument of personal revenge against the other. Not a very big thing to ask! But I for one would rest easier if I knew such an oath had been taken.”

Lepidus rose to his feet wearily. “My personal opinion of your proposal, Philippus, is that it is without a doubt the silliest thing I have ever heard of! However, if it will make the House any happier and allow Quintus Lutatius and me to go about our tasks more expeditiously, then I for one am willing to swear.”

“I am in full accord, Marcus Aemilius,” said Catulus. “Now may we all go home?”

*

“What do you think Philippus was up to?” asked Lepidus. of Brutus over dinner the following day.

“Truly I do not know,” said Brutus, shaking his head.

“Have you any idea, Servilia?” the senior consul asked.

“Not really, no,” she answered, frowning. “My husband gave me a general outline of what had been said last night, but I might be able to learn more if you could possibly provide me with a copy of the verbatim proceedings—that is, if the clerks took them down.”

So high had Lepidus’s opinion of Servilia’s political acumen become that he saw nothing untoward in this request, and agreed to give her the document on the morrow before he left Rome to recruit his four legions.

“I am beginning to think,” said Brutus, “that you stand no chance to improve the lot of the Etrurian and Umbrian towns which weren’t directly involved in Carbo’s war. There are just too many men like Philippus in the Senate, and they don’t want to hear what you have to say.”

The pacifying of at least some of the Umbrian districts mattered to Brutus, who was the largest landowner in Umbria after Pompey; he wanted no soldier settlements adjoining his own lands. These were mostly around Spoletium and Iguvium, two areas already sequestrated. That they had not yet received any veteran settlers was due to two factors: the torpor of the commissions set up to deal with apportionment, and the departure of fourteen of Sulla’s old legions for service in the Spains twenty months ago. It was only this second factor had enabled Lepidus to bring on his legislation; had all twenty-three of Sulla’s legions remained in Italy to be demobilized as originally planned, then Spoletium and Iguvium would have seen their full complement of veterans already.

“What Philippus had to say yesterday was an absolute shock,” said Lepidus, flushing with anger at the memory of it. “I just can’t believe those idiots! I truly thought that when I answered Philippus, I would win them around—I spoke good sense, Servilia, plain good sense! And yet they let Philippus bluff them into extracting that ridiculous oath we all had to swear this morning up in Semo Sancus Dius Fidius!”

“Which means they’re ready to be swayed even more,” she said. “What worries me is that you won’t be in the House to counter the old mischief—maker the next time he speaks—and speak, he will! He’s hatching something.”

“I don’t know why we call him old,” said Brutus, who was prone to digress. “He isn’t really that old—fifty-eight. And though he looks as if he might be carried off tomorrow by an apoplexy, it’s my guess he won’t be. That would be too good to be true!”

But Lepidus was tired of digressions and speculations, and suddenly got down to serious business. “I’m off to Etruria to recruit,” he said, “and I’d like you to join me as soon as possible, Brutus. We had planned to work as a team next year, but I think it behooves us to start now. There’s nothing coming up in your court which won’t wait until next year and a new judge, so I shall ask that you be seconded to me as my senior legate immediately.”

Servilia looked concerned. “Is it wise to recruit your men in Etruria?” she asked. “Why not go to Campania?”

“Because Catulus got in ahead of me and took Campania for himself. Anyway, my own lands and contacts are in Etruria, not south of Rome. I’m comfortable there, I know many more people.”

“But that’s what perturbs me, Lepidus. I suspect Philippus might make much of it, continue to throw doubts into everyone’s minds as to your ultimate intentions. It doesn’t look good to be recruiting in an area seething with potential revolt.”

“Let Philippus!” said Lepidus scornfully.

*

The Senate let Philippus. As Quinctilis passed into Sextilis and recruitment proceeded at a great rate, Philippus made it his duty to keep a watchful eye upon Lepidus through, it seemed, an amazingly large and efficient network of agents. No time did he waste upon watching Catulus in Campania; his four legions were filling up rapidly with Sulla’s oldest retainers, bored with civilian life and farming, eager for a new campaign not too far from home. The trouble was that the men enlisting in Etruria were not Sulla’s veterans. Rather they were green young men of the region, or else veterans who had fought for Carbo and his generals and managed to be missing from the ranks when surrender occurred. Most of Sulla’s men resettled in Etruria elected to remain on their allotments to protect them, or else hied themselves off to Campania to enlist in the legions of Catulus.

All through September did Philippus roar in the House while both Catulus and Lepidus, their enlistments filled, bent their energies to training and refining their armies. Then at the very beginning of October, Philippus managed to weary the Senate into demanding that Lepidus return to hold the curule elections in Rome. The summons went north to Lepidus’s camp outside Saturnia, and Lepidus’s answer came back by the same courier.

“I cannot leave at this juncture,” it said baldly. “You must either wait for me or appoint Quintus Lutatius in my stead.”

Quintus Lutatius Catulus was ordered to return from Campania—but not to hold the elections; it was no part of Philippus’s plan to allow Lepidus this grace, and Cethegus had allied himself with Philippus so firmly that whatever Philippus wanted was assented to by three quarters of the House.

In all this no move had yet been made against Faesulae, which had locked its gates and sat back to see what happened, very pleased that Rome could not seem to agree upon what to do.

A second summons was dispatched to Lepidus demanding that he return to Rome at once to hold the elections; again Lepidus refused. Both Philippus and Cethegus now informed the senators that Lepidus must be considered to be in revolt, that they had proof of his dealings and agreements with the refractory elements in Etruria and Umbria—and that his senior legate, the praetor Marcus Junius Brutus, was equally involved.

Said Servilia in a letter to Lepidus:

I believe I have finally managed to work out what is behind Philippus’s conduct, though I have been able to find no definite proof of my suspicions. However, you may take it that whatever and whoever is behind Philippus is also behind Cethegus.

I studied the verbatim text of that first speech Philippus made over and over again, and had many a cozy chat with every woman in a position to know something. Except for the loathsome Praecia, who is now queening it in the Cethegus menage, it would appear exclusively. Hortensia knows nothing because I believe Catulus her husband knows nothing. However, I finally obtained the vital clue from Julia, the widow of Gaius Marius—you perceive how far I have extended my net pursuing my enquiries!

Her once—upon—a—time daughter-in-law, Mucia Tertia, is now married to that young upstart from Picenum, Gnaeus Pompeius who has the temerity to call himself Magnus. Not a member of the Senate, but very rich, very brash, very anxious to excel. I had to be extremely careful that I did not give Julia any impression that I might be sniffing for information, but she is a frank person once she reposes her trust in someone, and she was inclined to do so from the outset because of my husband’s father’s loyalty to Gaius Marius—whom, you might remember, he accompanied into exile during Sulla’s first consulship.

It turns out too that Julia has detested Philippus ever since he sold himself to Gaius Marius many years ago; apparently Gaius Marius despised the man even as he used him. So when at my third visit (I thought it wise to establish Julia’s full trust before mentioning Philippus in more than a passing fashion) I drew the conversation around to the present situation and Philippus’s possible motives in making you his victim, Julia mentioned that she thought from something Mucia Tertia had said to her during her last visit to Rome that Philippus is now in the employ of Pompeius! As is none other than Cethegus!

I enquired no further. It really wasn’t necessary. From the time of that initial speech, Philippus has harped tirelessly upon Sulla’s special clause authorizing the Senate to look outside its own ranks for a military commander or a governor should a good man not be available within its own ranks. Still puzzled as to what this could have to do with the present situation? I confess I was! Until, that is, I sat and mentally reviewed Philippus’s conduct over the past thirty-odd years.

I concluded that Philippus is simply working for his master, if his master be in truth Pompeius. Philippus is not a Gaius Gracchus or a Sulla; he has no grand strategy in mind whereby he will manipulate the Senate into dismissing all of you currently embroiled in this campaign against Faesulae and appointing Pompeius in your stead. He probably knows quite well that the Senate will not do that under any circumstances—there are too many capable military men sitting on the Senate’s benches at the moment. If both the consuls should fail—and at this stage it is difficult to see why either of you should—there is none other than Lucullus ready to step into the breach, and he is a praetor this year, so has the imperium already.

No, Philippus is merely making as big a fuss as he can in order to have the opportunity to remind the Senate that Sulla’s special commission clause does exist. And presumably Cethegus is willing to support him because he too somehow is caught in Pompeius’s toils. Not from want of money, obviously! But there are other reasons than money, and Cethegus’s reasons could be anything.

Therefore, my dear Lepidus, it seems to me that you are to some extent an incidental victim, that your courage in speaking up for what you believe even though it runs counter to most of the Senate has presented Philippus with a target he can use to justify whatever colossal amount it is that Pompeius is paying him. He’s simply lobbying for a man who is not a senator but deems it worthwhile to have a strong faction within the Senate against the day when hi§ services might be needed.

In fairness, I could be completely wrong. However, I do not think I am.

“It makes a great deal more sense than anything else I’ve heard,” said Lepidus to his correspondent’s husband after he had read her letter out loud for Brutus’s benefit.

“And I agree with Servilia,” said Brutus, awed. “I doubt she’s wrong. She rarely is.”

“So, my friend, what do I do? Return to Rome like a good boy, hold the curule elections and pass then into obscurity—or do I attempt what the Etrurian leaders want of me and lead them against Rome in open rebellion?”

It was a question Lepidus had asked himself many times since he had reconciled himself to the fact that Rome would never permit him to restore Etruria and Umbria to some semblance of normality and prosperity. Pride was in his dilemma, and a certain driving need to stand out from the crowd, albeit that crowd be composed of Roman consulars. Since the death of his wife the value of his actual life had diminished in his own eyes to the point where he held it of scant moment; he had quite lost sight of the real reason for her suicide, which was that their sons should be freed from political reprisals at any time in the future. Scipio Aemilianus and Lucius were with him wholeheartedly and young Marcus was still a child; he it was who fulfilled the Lepidus family’s tradition by being the male child born with a caul over his face, and everyone knew that phenomenon meant he would be one of Fortune’s favorites throughout a long life. So why ought Lepidus worry about any of his sons?

For Brutus the dilemma was somewhat different, though he did not fear defeat. No, what attracted Brutus to the Etrurian scheme was the culmination of eight years of marriage to the patrician Servilia: the knowledge that she considered him plain, humdrum, unexciting, spineless, contemptible. He did not love her, but as the years went by and his friends and colleagues esteemed her opinions on political matters more and more, he came to realize that in her woman’s shell there resided a unique personage whose approval of him mattered. In this present situation, for instance, she had written not to him but to the consul, Lepidus. Passing him over as unimportant. And that shamed him. As he now understood it shamed her also. If he was to retrieve himself in her eyes, he would have to do something brave, high—principled, distinctive.

Thus it was that Brutus finally answered Lepidus’s question instead of evading it. He said, “I think you must attempt what the elders want of you and lead Etruria and Umbria against Rome.”

“All right,” said Lepidus, “I will. But not until the New Year, when I am released from that silly oath.”

*

When the Kalends of January arrived, Rome had no curule magistrates; the elections had not been held. On the last day of the old year Catulus had convened the Senate and informed it that on the morrow it would have to send the fasces to the temple of Venus Libitina and appoint the first interrex. This temporary supreme magistrate called the interrex held office for five days only as custodian of Rome; he had to be patrician, the leader of his decury of senators, and in the case of the first interrex, the senior patrician in the House. On the sixth day he was succeeded as interrex by the second most senior patrician in the House also leader of his decury; the second interrex was empowered to hold the elections.

So at dawn on New Year’s Day the Senate formally appointed Lucius Valerius Flaccus Princeps Senatus the first interrex and those men who intended to stand for election as consuls and praetors went into a flurry of hasty canvassing. The interrex sent a curt message to Lepidus ordering him to leave his army and return to Rome forthwith, and reminding him that he had sworn an oath not to turn his legions upon his colleague.

At noon on the third day of Flaccus Princeps Senatus’s term, Lepidus sent back his reply.

I would remind you, Princeps Senatus, that I am now proconsul, not consul. And that I kept my oath, which does not bind me now I am proconsul, not consul. I am happy to give up my consular army, but would remind you that I am now proconsul and was voted a proconsular army, and will not give up this proconsular army. As my consular army consisted of four legions and my proconsular army also consists of four legions, it is obvious that I do not have to give up anything.

However, I am willing to return to Rome under the following circumstances: that I am re-elected consul; that every last iugerum of sequestrated land throughout Italy be returned to its original owner; that the rights and properties of the sons and grandsons of the proscribed be restored to them; and that their full powers be restituted to the tribunes of the plebs.

“And that,” said Philippus to the members of the Senate, “should tell even the densest senatorial dunderhead what Lepidus intends! In order to give him what he demands, we would have to tear down the entire constitution Lucius Cornelius Sulla worked so hard to establish, and Lepidus knows very well we will not do that. This answer of his is tantamount to a declaration of war. I therefore beseech the House to pass its senatus consultant de re publica defendenda.”

But this required impassioned debate, and so the Senate did not pass its Ultimate Decree until the last day of Flaccus’s term as first interrex. Once it was passed the authority to defend Rome against Lepidus was formally conferred upon Catulus, who was ordered to return to his army and prepare for war.

On the sixth day of January, Flaccus Princeps Senatus stood down and the Senate appointed its second interrex, who was Appius Claudius Pulcher, still lingering in Rome recovering from his long illness. And since Appius Claudius was actually feeling much better, he flung himself into the task of convening the Centuriate Assembly and holding the curule elections. These would occur, he announced, within the Servian Walls on the Aventine in two days’ time, this site being outside the pomerium but adequately protected from any military action by Lepidus.

“It’s odd,” said Catulus to Hortensius just before he left for Campania, “that after so many years of not enjoying the privilege of free choice in the matter of our magistrates, we should find it so difficult to hold an election at all. Almost as if we were drifting into the habit of allowing someone to do everything for us, like a mother for her babies.”

“That,” said Hortensius in freezing tones, “is sheer fanciful claptrap, Quintus! The most I am prepared to concede is that it is an extraordinary coincidence that our first year of free choice in the matter of our magistrates should also throw up a consul who ignored the tenets of his office. We are now conducting these elections, I must point out to you, and the governance of Rome will proceed in future years as it was always intended to proceed!”

“Let us hope then,” said Catulus, offended, “that the voters will choose at least as wisely as Sulla always did!”

But it was Hortensius who had the last word. “You are quite forgetting, my dear Quintus, that it was Sulla chose Lepidus!”

On the whole the leaders of the Senate (including Catulus and Hortensius) professed themselves pleased with the wisdom of the electors. The senior consul was an elderly man of sedentary habit but known ability, Decimus Junius Brutus, and the junior consul was none other than Mamercus. Clearly the electors held the same high opinion of the Cottae as Sulla had, for last year Sulla had picked Gaius Aurelius Cotta as one of his praetors, and this year the voters returned his brother Marcus Aurelius Cotta among the praetors; the lots made him praetor peregrinus.

Having remained in Rome to see who was returned, Catulus promptly offered supreme command in the war against Lepidus to the new consuls. As he expected, Decimus Brutus refused on the grounds of his age and lack of adequate military experience; it was Mamercus who was bound to accept. Just entering his forty-fourth year, Mamercus had a fine war record and had served under Sulla in all his campaigns. But unforeseen events and Philippus conspired against Mamercus. Lucius Valerius Flaccus the Princeps Senatus, colleague in the second—last consulship of Gaius Marius, dropped dead the day after he stepped down from office as first interrex, and Philippus proposed that Mamercus be appointed as a temporary Princeps Senatus.

“We cannot do without a Leader of the House at this present time,” Philippus said, “though it has always been the task of the censors to appoint him. By tradition he is the senior patrician in the House, but legally it is the right of the censors to appoint whichever patrician senator they consider most suitable. Our senior patrician senator is now Appius Claudius Pulcher, whose health is not good and who is proceeding to Macedonia anyway. We need a Leader of the House who is young and robust—and present in Rome! Until such time as we elect a pair of censors, I suggest that we appoint Mamercus Aemilius Lepidus Livianus as a caretaker Princeps Senatus. I also suggest that he should remain within Rome until things settle down. It therefore follows that Quintus Lutatius Catulus should retain his command against Lepidus.”

“But I am going to Nearer Spain to govern!” cried Catulus.

“Not possible,” said Philippus bluntly. “I move that we direct our good Pontifex Maximus Metellus Pius, who is prorogued in Further Spain, to act as governor of Nearer Spain also until we can see our way clear to sending a new governor.”

As everyone was in favor of any measure which kept the stammering Pontifex Maximus a long way from Rome and religious ceremonies, Philippus got his way. The House authorized Metellus Pius to govern Nearer Spain as well as his own province, made Mamercus a temporary Princeps Senatus, and confirmed Catulus in his command against Lepidus. Very disappointed, Catulus took himself off to form up his legions in Campania, while an equally disappointed Mamercus remained in Rome.

*

Three days later word came that Lepidus was mobilizing his four legions and that his legate Brutus had gone to Italian Gaul to put its two garrison legions at Bononia, the intersection of the Via Aemilia and the Via Annia, where they would be perfectly poised to reinforce Lepidus. Still toying with revolt because they had suffered the loss of all their public lands, Clusium and Arretium could be expected to offer Brutus every assistance in his march to join Lepidus—and to block any attempt by Catulus to prevent his joining up with Lepidus.

Philippus struck.

“Our supreme commander in the field, Quintus Lutatius Catulus, is still to the south of Rome—has not in fact yet left Campania. Lepidus is moving south from Saturnia already,” said Philippus, “and will be in a position to stop our commander-in-chief sending any of his troops to deal with Brutus in Italian Gaul. Besides which, I imagine our commander-in-chief will need all four of his legions to contain Lepidus himself. So what can we possibly do about Brutus, who holds the key to Lepidus’s success in his hands? Brutus must be dealt with—and dealt with smartly! But how? At the moment we have no other legions under the eagles in Italy, and the two legions of Italian Gaul belong to Brutus. Not even a Lucullus—were he still in Rome instead of on his way to govern Africa Province—could assemble and mobilize at least two legions quickly enough to confront Brutus.”

The House listened gloomily, having finally been brought to realize that the years of civil strife were not over just because Sulla had made himself Dictator and striven mightily with his laws to stop another man from marching on Rome. With Sulla not dead a year yet, here was another man coming to impose his will upon his hapless country, here were whole tracts of Italy in arms against the city the Italians had wantedto belong to so badly in every way. Perhaps there were some among the voiceless ranks who were honest enough to admit that it was largely their own fault Rome was brought to this present pass; but if there were, not one of them spoke his thoughts aloud. Instead, everyone gazed at Philippus as if at a savior, and trusted to him to find a way out.

“There is one man who can contain Brutus at once,” said Philippus, sounding smug. “He has his father’s old troops—and indeed his own old troops!—working for him on his estates in northern Picenum and Umbria. A much shorter march to Brutus than from Campania! He has been Rome’s loyal servant in the past, as was his father Rome’s loyal servant before him. I speak, of course, of the young knight Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus. Victor at Clusium, victor in Sicily, victor over Africa and Numidia. It was not for nothing that Lucius Cornelius Sulla permitted this young knight to triumph! This young knight is our brightest hope! And he is in a position to contain Brutus within days!”

The newly appointed temporary Princeps Senatus and junior consul shifted on his curule chair, frowning. “Gnaeus Pompeius is not a member of the Senate,” Mamercus said, “and I cannot like the idea of giving any kind of command to someone outside our own.”

“I agree with you completely, Mamercus Aemilius!” said Philippus instantly. “No one could like it. But can you offer a better alternative? We have the constitutional power in times of emergency to look outside the Senate for our military answer, and this power was given to us by none other than Sulla himself. No more conservative man than Sulla ever lived, nor a man more attached to the perpetuation of the mos maiorum. Yet he it was who foresaw just this present situation—and he it was who provided us with an answer.”

Philippus stayed by his stool (as Sulla had directed all speakers must), but he turned around slowly in a circle to look at the tiers of senators on both sides of the House. As orator and presence he had grown in stature since the time when he had set out to ruin Marcus Livius Drusus; these days there were no ludicrous temper tantrums, no storms of abuse.

“Conscript Fathers,” he said solemnly, “we have no time to waste in debate. Even as I speak, Lepidus is marching on Rome. May I respectfully ask the senior consul Decimus Junius Brutus to put a motion before the House? Namely, that this body authorize the knight Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus to raise his old legions and march to contend with Marcus Junius Brutus in the name of the Senate and People of Rome. Further, that this body confer a propraetorian status upon the knight Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus.”

Decimus Brutus had opened his mouth to consent when Mamercus prevented him, one hand on the senior consul’s arm. “I will agree to your putting that motion before the House for a vote, Decimus Junius,” he said, “but not until Lucius Marcius Philippus has clarified one phrase he used in wording his motion! He said, ‘to raise his old legions’ instead of specifying how many legions! No matter how stellar Gnaeus Pompeius’s military record might be, he is not a member of the Senate! He cannot be given the authority to raise legions in Rome’s name to however many he may himself consider enough. I say that the motion must specify the exact number of legions this House authorizes Gnaeus Pompeius to raise, and I say further that the number of legions be limited to two. Brutus the governor of Italian Gaul has two legions of relatively inexperienced soldiers, the permanent garrison of that province. It ought not to take more than two legions of hoary old Pompeian veterans to deal with Brutus.”

This perceptive opposition did not please Philippus, but he deemed it wise to accede; Mamercus was of that slow and steady kind who somehow always managed to accumulate a lot of senatorial clout—and he was married to Sulla’s daughter.

“I beg the House’s pardon!” cried Philippus. “How sloppy of me! And I thank our esteemed Princeps Senatus and junior consul for his timely intervention. I meant to say two legions, of course. Let the motion be put to the House, Decimus Junius, with that exact number of legions.”

The motion was put, and the motion was passed without one single dissenting voice. Cethegus had raised his arms above his head in a stretch and a yawn, the signal to all his followers on the back benches that they were to vote in the affirmative. And because the motion dealt with war, the senatorial resolution carried the force of law with it; in war and in foreign matters the various Assemblies of the Roman People no longer had a say.

*

It was, after all that political maneuvering, a hasty and pathetic little war, hardly deserving of the name. Even though Lepidus had started out to march on Rome considerably earlier than Catulus left Campania, still Catulus beat him to Rome and occupied the Campus Martius. When Lepidus did appear across the river in Transtiberim (he had come down the Via Aurelia), Catulus barred and garrisoned all the bridges, and thereby forced Lepidus to march north to the Mulvian Bridge. Thus it was that the two armies came to grips on the northeastern side of the Via Lata under the Servian Walls of the Quirinal; in that place most of the fighting occurred. Some fierce clashes of arms elevated the battle beyond a rout, but Lepidus turned out to be a hopeless tactician, incapable of deploying his men logically and quite incapable of winning.

An hour after the two sides met, Lepidus was in full retreat back to the Mulvian Bridge, with Catulus in hot pursuit. North of Fregenae he turned and fought Catulus again, but only to secure his flight to Cosa. From Cosa he managed to escape to Sardinia, accompanied by twenty thousand of his foot soldiers and fifteen hundred cavalry troopers. It was his intention to restructure his army in Sardinia, then return to Italy and try again. With him went his middle son, Lucius, the Carboan ex-governor Marcus Perperna Veiento, and Cinna’s son. But Lepidus’s eldest son, Scipio Aemilianus, declined to leave Italy. Instead he barricaded himself and his legion inside the old and formidable fortress on the Alban Mount above Bovillae, and there withstood siege.

The much-publicized return to Italy from Sardinia never came to pass. The governor of Sardinia was an old ally of Lucullus’s, one Lucius Valerius Triarius, and he resisted Lepidus’s occupation bitterly. Then in April of that unhappy year Lepidus died still in Sardinia; his troops maintained that what killed him was a broken heart, mourning for his dead wife. Perperna Veiento and Cinna’s son took ship from Sardinia to Liguria, and thence marched their twenty thousand foot and fifteen hundred horse along the Via Domitia to Spain and Quintus Sertorius. With them went Lucius, Lepidus’s middle son.

The eldest son, Scipio Aemilianus, proved the most militarily competent of the rebels, and held out in Alba Longa for some time. But eventually he was forced to surrender; following orders from the Senate, Catulus executed him.

If ignominy was to set the standard of events, Brutus fared far the worst. While ever he heard nothing from Lepidus he held his two legions in Italian Gaul at the major intersection of Bononia; and thus allowed Pompey to steal a march on him. That young man (now some twenty-eight years old) had of course already been mobilized when Philippus secured him his special commission from the Senate. But instead of bringing his two legions up from Picenum to Ariminum and then inland along the Via Aemilia, Pompey chose to go down the Via Flaminia toward Rome. At the intersection of this road with the Via Cassia north to Arretium and thence to Italian Gaul, he turned onto the Via Cassia. By doing this he prevented Brutus from joining Lepidus—had Brutus ever really thought he might.

When he heard of Pompey’s approach up the Via Cassia, Brutus retreated into Mutina. This big and extremely well-fortified town was stuffed with clients of the Aemilii, Lepidus as well as Scaurus. It therefore welcomed Brutus gladly. Pompey duly arrived; Mutina was invested. The city held out until Brutus heard of the defeat and flight of Lepidus, and his death in Sardinia. Once it became clear that Lepidus’s troops were now absolutely committed to Quintus Sertorius in Spain, Brutus despaired. Rather than put Mutina through any further hardship, he surrendered.

“That was sensible,” said Pompey to him after Pompey had entered the city.

“Both sensible and expedient,” said Brutus wearily. “I fear, Gnaeus Pompeius, that I am not by nature a martial man.”

“That’s true.”

“I will, however, go to my death with grace.”

The beautiful blue eyes opened even wider than usual. ‘ To your death?’’ asked Pompey blankly. ‘ There is no need for that, Marcus Junius Brutus! You’re free to go.”

It was Brutus’s turn to open his eyes wide. “Free? Do you mean it, Gnaeus Pompeius?”

“Certainly!” said Pompey cheerfully. “However, that does not mean you’re free to raise fresh resistance! Just go home.”

“Then with your permission, Gnaeus Pompeius, I will proceed to my own lands in western Umbria. My people there need calming.”

“That’s fine by me! Umbria is my patch too.”

But after Brutus had ridden out of Mutina’s western gate, Pompey sent for one of his legates, a man named Geminius who was a Picentine of humble status and inferior rank; Pompey disliked subordinates whose station in life was equal to his own.

“I’m surprised you let him go,” said Geminius.

“Oh, I had to let him go! My standing with the Senate is not yet so high that I can order the execution of a Junius Brutus without overwhelming evidence. Even if I do have a propraetorian imperium. So it’s up to you to find that overwhelming evidence.”

“Only tell me what you want, Magnus, and it will be done.”

“Brutus says he’s going to his own estates in Umbria. Yet he’s chosen to head northwest on the Via Aemilia! I would have said that was the wrong way, wouldn’t you? Well, perhaps he’s heading cross—country. Or perhaps he’s looking for more troops. I want you to follow him at once with a good detachment of cavalry—five squadrons ought to be enough,” said Pompey, picking his teeth with a thin sliver of wood. “I suspect he’s looking for more troops, probably in Regium Lepidum. Your job is to arrest him and execute him the moment he seems treasonous. That way there can be no doubt that he’s a double traitor, and no one in Rome can object when he dies. Understood, Geminius?’’

“Completely.”

What Pompey did not explain to Geminius was the ultimate reason for this second chance for Brutus. Kid Butcher was aiming for the command in Spain against Sertorius, and his chances of getting it were much greater if he could find an excuse for not demobilizing. Could he make it appear that Italian Gaul was potentially rebellious right along the length of the Via Aemilia, then he had every excuse for lingering there with his army now that the war was over. He would be far enough away from Rome not to seem to present any threat to the Senate, yet he would still be under arms. Ready to march for Spain.

Geminius did exactly as he was told. When Brutus arrived in the township of Regium Lepidum some distance to the northwest of Mutina, he was welcomed joyfully. As the name of the place indicated, it was populated by clients of the Aemilii Lepidi, and naturally it offered to fight for Brutus if he wished. But before Brutus could answer, Geminius and his five squadrons of cavalry rode in through the open gates. There in the forum of Regium Lepidum, Geminius publicly adjudged Marcus Junius Brutus an enemy of Rome, and cut his head off.

Back went the head to Pompey in Mutina, together with a laconic message from Geminius to the effect that he had surprised Brutus in the act of organizing a fresh insurrection, and that in Geminius’s opinion Italian Gaul was unstable.

Off went Pompey’s report to the Senate:

For the time being I consider it my duty to garrison Italian Gaul with my two legions of veterans. The troops Brutus commanded I disbanded as disloyal, though I did not punish them beyond removing their arms and armor. And their two eagles of course. I consider the conduct of Regium Lepidum a symptom of the general unrest north of the border, and hope this explains my decision to stay.

I have not dispatched the head of the traitor Brutus with this record of my deeds because he was at the time of his death a governor with a propraetorian imperium, and I don’t think the Senate would want to pin it up on the rostra. Instead, I have sent the ashes of body and head to his widow for proper interment. In this I hope I have not erred. It was no part of my intentions to execute Brutus. He brought that fate upon himself.

May I respectfully request that my own imperium be permitted to stand for the time being? I can perform a useful function here in Italian Gaul by holding the province for the Senate and People of Rome.

The Senate under Philippus’s skillful guidance pronounced those men who had taken part in Lepidus’s rebellion sacer, but because the horrors of the proscriptions still lingered, did not exact any reprisals against their families; the crude pottery jar containing his ashes in her lap, the widow of Marcus Junius Brutus could relax. Her six-year-old son’s fortune was safe, though it would be up to her to ensure that he did not suffer political odium when he grew up.

Servilia told the child of his father’s death in a way which gave him to understand that he was never to admire or assist his father’s murderer, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, the Picentine upstart. The boy listened, nodding solemnly. If the news that he now had no father upset him or grieved him, he gave no sign.

He had not yet sprung into speedy growth, but remained a weedy, undersized little boy with spindly legs and a pouting face. Very dark of hair and eye and olive of skin, he had produced a certain juvenile prettiness which his besotted mama saw as permanent beauty, and his tutor spoke highly of his ability to read and write and calculate (what the tutor did not say, however, was that little Brutus entirely lacked an original bent, and imagination). Naturally Servilia had no intention of ever sending Brutus to school with other boys; he was too sensitive, too intelligent, too precious—someone might pick on him!

Only three members of her family had come to pay their condolences to Servilia, though two of those were, strictly speaking, not close relatives.

After the last of their various parents, grandparents and others had died, the only surviving person linked to them by blood, Uncle Mamercus, had placed the six orphaned children of his brother and sister in the charge of a Servilius Caepio cousin and her mother. These two women, Gnaea and Porcia Liciniana, now came to call—a courtesy Servilia could well have done without. Gnaea remained the dour and silent subordinate of her overpowering mother; at almost thirty years of age, she was even plainer and flatter of chest than she had been in her late adolescence. Porcia Liciniana dominated the conversation. As she had done all of her life.

“Well, Servilia, I never thought to see you a widow at such an early age, and I’m sorry for you,” said this formidable lady. “It always seemed remarkable to me that Sulla spared your husband and his father from the proscription lists, though I assumed that was because of you. It might have been awkward—even for Sulla!—to proscribe the father-in-law of his own son-in-law’s niece, but he really ought to have done so. Old Brutus stuck to Gaius Marius and then Carbo like a moth melted into a wax candle. It had to have been his son’s marriage to you saved them both. And you would think the son would have learned, wouldn’t you? But no! Off he went to serve an idiot like Lepidus! Anyone with any sense could have seen that business would never prosper.”

“Quite so,” said Servilia colorlessly.

“I’m sorry too,” said Gnaea gruffly, contributing her mite.

But the glance Servilia bestowed upon this poor creature held neither love nor pity; Servilia despised her, though she did not loathe her as she did the mother.

“What will you do now?’’ asked Porcia Liciniana.

“Marry again as soon as I can.”

“Marry again! That is not fitting for one of your rank. I did not remarry after I was widowed.”

“I imagine no one asked you,” said Servilia sweetly.

Thick—skinned though she was, Porcia Liciniana nonetheless felt the sting of the acid in this statement, and rose majestically to her feet. “I’ve done my duty and paid my condolences,” she said. “Come, Gnaea, it’s time to go. We mustn’t hinder Servilia in her search for a new husband.”

“And good riddance to you, you old verpa!” said Servilia to herself after they had gone.

Quite as unwelcome as Porcia Liciniana and Gnaea was her third visitor, who arrived shortly afterward. The youngest of the six orphans, Marcus Porcius Cato was Servilia’s half brother through their common mother, sister to Drusus and Mamercus.

“My brother Caepio would have come,” said young Cato in his harsh and unmelodic voice, “except that he’s out of Rome with Catulus’s army—a contubernalis, if you know that term.”

“I know it,” said Servilia gently.

But the thickness of Porcia Liciniana’s skin was as air compared to Marcus Porcius Cato’s, so this sally was ignored. He was now sixteen years old and a man, but he still lived in the care of Gnaea and her mother, as did his full sister, Porcia.

Mamercus had sold Drusus’s house as too large some time ago; they all occupied Cato’s father’s house these days.

Though the massive size of his blade—thin eagle’s nose would never allow him to be called handsome, Cato was actually a most attractive youth, clear—skinned and wide—shouldered. His large and expressive eyes were a soft grey, his closely cropped hair an off—red that shaded to chestnut, and his mouth quite beautiful. To Servilia, however, he was an absolute monster—loud, slow to learn, insensitive, and so pugnaciously quarrelsome that he had been a thorn in the side of his older siblings from the time he began to walk and talk.

Between them lay ten years of age and different fathers, but more than that; Servilia was a patrician whose family went back to the time of the Kings of Rome, whereas Cato’s branch of his family went back to a Celtiberian slave, Salonia, who had been the second wife of Cato the Censor. To Servilia, this slur her mother had brought upon her own and her husband’s families was an intolerable one, and she could never set eyes upon any of her three younger siblings without grinding her teeth in rage and shame. For Cato these feelings were undisguised, but for Caepio, supposed to be her own full brother (she knew he was not), what she felt had to be suppressed. For decency’s sake. Rot decency!

Not that Cato felt any social stigma; he was inordinately proud of his great—grandfather the Censor, and considered his lineage impeccable. As noble Rome had forgiven Cato the Censor this second marriage (founded as it had been in a sly revenge against his snobbish son by his first wife, a Licinia), young Cato could look forward to a career in the Senate and very likely the consulship.

“Uncle Mamercus turned out to have picked you an unsuitable husband,” said Cato.

“I deny that,” said Servilia in level tones. “He suited me well. He was, after all, a Junius Brutus. Plebeian, perhaps, but absolutely noble on both sides.”

“Why can you never see that ancestry is far less important than a man’s deeds?” demanded Cato.

“It is not less important, but more.”

“You’re an insufferable snob!”

“I am indeed. I thank the gods for it.”

“You’ll ruin your son.”

“That remains to be seen.”

“When he’s a bit older I’ll take him under my wing. That will knock all the social pretensions out of him!”

“Over my dead body.”

“How can you stop me? The boy can’t stay plastered to your skirts forever! Since he has no father, I stand in loco parentis.”

“Not for very long. I shall remarry.”

“To remarry is unbecoming for a Roman noblewoman! I would have thought you would have set out to emulate Cornelia the Mother of the Gracchi.”

“I am too sensible. A Roman noblewoman of patrician stock must have a husband to ensure her pre-eminence. A husband, that is, who is as noble as she is.”

He gave vent to a whinnying laugh. “You mean you’re going to marry some overbred buffoon like Drusus Nero!”

“It’s my sister Lilla who is married to Drusus Nero.”

“They dislike each other.”

“My heart bleeds for them.”

“I shall marry Uncle Mamercus’s daughter,” said Cato smugly.

Servilia stared, snorted. “You will not! Aemilia Lepida was contracted to marry Metellus Scipio years ago, when Uncle Mamercus was with his father, Pius, in Sulla’s army. And compared to Metellus Scipio, Cato, you’re a complete mushroom!”

“It makes no difference. Aemilia Lepida might be engaged to Metellus Scipio, but she doesn’t love him. They fight all the time, and who does she turn to when he makes her unhappy? To me, of course! I shall marry her, be sure of it!”

“Is there nothing under the sun that can puncture your unbelievable complacence?” she demanded.

“If there is, I haven’t met it,” he said, unruffled.

“Don’t worry, it’s lying in wait somewhere.”

Came another of those loud, neighing laughs. “You hope!”

“I don’t hope. I know.”

“My sister Porcia is all settled,” Cato said, not wanting to change the subject, simply imparting fresh information.

“To an Ahenobarbus, no doubt. Young Lucius?”

“Correct. To young Lucius. I like him! He’s a fellow with the right ideas.”

“He’s almost as big an upstart as you are.”

“I’m off,” said Cato, and got up.

“Good riddance!” Servilia said again, but this time to its object’s face rather than behind his back.

Thus it was that Servilia went to her empty bed that night plunged into a mixture of gloom and determination. So they did not approve of her intention to remarry, did they? So they all considered her finished as a force to be reckoned with, did they?

“They’re wrong!” she said aloud, then fell asleep.

In the morning she went to see Uncle Mamercus, with whom she had always got on very well.

“You are the executor of my husband’s will,” she said. “I want to know what becomes of my dowry.”

“It’s still yours, Servilia, but you won’t need to use it now you’re a widow. Marcus Junius Brutus has left you sufficient money in your own right to live comfortably, and his son is now a very wealthy young boy.”

“I wasn’t thinking of continuing to live alone, Uncle. I want to remarry if you can find me a suitable husband.”

Mamercus blinked. “A rapid decision.”

“There is no point in delaying.”

“You can’t marry again for another nine months, Servilia.”

“Which gives you plenty of time to find someone for me,” said the widow. “He must be at least as wellborn and wealthy as Marcus Junius, but preferably somewhat younger.”

“How old are you now?”

“Twenty-seven.”

“So you’d like someone about thirty?”

“That would be ideal, Uncle Mamercus.”

“Not a fortune—hunter, of course.”

She raised her brows. “Not a fortune—hunter!”

Mamercus smiled. “All right, Servilia, I’ll start making enquiries on your behalf. It ought not to be difficult. Your birth is superlative, your dowry is two hundred talents, and you have proven yourself fertile. Your son will not be a financial burden for any new husband, nor will you. Yes, I think we ought to be able to do quite well for you!”

“By the way, Uncle,” she said as she rose to go, “are you aware that young Cato has his eye on your daughter?”

“What?”

“Young Cato has his eye on Aemilia Lepida.”

“But she’s already engaged—to Metellus Scipio!”

“So I told Cato, but he seems not to regard this engagement as an impediment. I don’t think, mind you, that Aemilia Lepida has any idea in her mind of exchanging Metellus Scipio for Cato. But I would not be doing my duty to you, Uncle, if I failed to inform you what Cato is going around saying.”

“They’re good friends, it’s true,” said Mamercus, looking perturbed, “but he’s exactly Aemilia Lepida’s age! That usually means girls aren’t interested.”

“I repeat, I don’t know that she is interested. All I’m saying is that Cato is interested. Nip it in the bud, Uncle—nip it in the bud!”

And that, said Servilia to herself as she emerged into the quiet street on the Palatine where Mamercus and Cornelia Sulla lived, will put you in your place, Marcus Porcius Cato! How dare you look as high as Uncle Mamercus’s daughter! Patrician on both sides!

Home she went, very pleased with herself. In many ways she was not sorry that life had served this turn of widowhood upon her; though at the time she married him Marcus Junius Brutus had not seemed too old, eight years of marriage had aged him in her eyes, and she had begun to despair of bearing other children. One son was enough, but there could be no denying several girls would contribute much; if well dowered they would find eligible husbands who would prove of use politically to her son. Yes, the death of Brutus had been a shock. But a grief it was not.

Her steward answered the door himself.

“What is it, Ditus?”

“Someone has called to see you, domina.”

“After all these years, you Greek idiot, you ought to know better than to phrase your announcement that way!” she snapped, enjoying his involuntary shiver of fear. “Who has called to see me?’’

“He said he was Decimus Junius Silanus, lady.”

“He said he was Decimus Junius Silanus. Either he is who he says he is, or he is not. Which is it, Epaphroditus?”

“He is Decimus Junius Silanus, lady.”

“Did you put him in the study?”

“Yes, lady.”

Off she went still wrapped in her black palla, frowning as she strove to place a face together with the name Decimus Junius Silanus. The same Famous Family as her late husband, but of the branch cognominated Silanus because the original bearer of that nickname had been, not ugly like the leering Silanus face which spouted water into every one of Rome’s drinking and washing fountains, but apparently too handsome. Owning the same reputation as the Memmii, the Junii Silani men continued to be too handsome.

He had called, he said, extending his hand to the widow, to give her his condolences and offer her whatever assistance he might. “It is very difficult for you, I imagine,” he ended a little lamely, and blushed.

Certainly from his face he could not be mistaken for any but a Junius Silanus, for he was fair of hair and blue of eye and quite startlingly handsome. Servilia liked blond men who were handsome. She placed her hand in his for exactly the proper length of time, then turned and shed her palla upon the back of her late husband’s chair, revealing herself clad in more black. The color suited her because her skin was clear and pale, yet her eyes and hair were as jet as her widow’s weeds. She also had a sense of style which meant she dressed smartly as well as becomingly, and she looked to the dazzled man as elegantly perfect in the flesh as she had in his memory.

“Do I know you, Decimus Junius?” she asked, gesturing that he sit on the couch, and herself taking up residence on a chair.

“You do, Servilia, but it was some years ago. We met at a dinner party in the house of Quintus Lutatius Catulus in the days before Sulla became Dictator. We didn’t talk for long, but I do remember that you had recently given birth to a son.”

Her face cleared. “Oh, of course! Please forgive me for my rudeness.” She put a hand to her head, looked sad. “It’s just that so much has happened to me since then.”

“Think nothing of it,” he said warmly, then sat without a thing to say, his eyes fixed upon her face.

She coughed delicately. “May I offer you some wine?”

“Thank you, no.”

“I see you have not brought your wife with you, Decimus Junius. Is she well?”

“I have no wife.”

“Oh!”

Behind her closed and alluringly secretive face, the thoughts were racing. He fancied her! There could be no doubt about it, he fancied her! For some years, it seemed. An honorable man too. Knowing she was married, he had not ventured to increase his acquaintance with her or with her husband. But now that she was a widow he intended to be the first and stave off competition. He was very wellborn, yes—but was he wealthy? The eldest son, since he bore the first name of Decimus: Decimus was the first name of the eldest son in the Junii Silani. He looked to be about thirty, and that was right also. But was he wealthy? Time to fish.

“Are you in the Senate, Decimus Junius?”

“This year, actually. I’m a city quaestor.”

Good, good! He had at least a senatorial census. “Where are your lands, Decimus Junius?”

“Oh, all over the place. My chief country estate is in Campania, twenty thousand iugera fronting onto the Volturnus between Telesia and Capua. But I have river frontage lands on the Tiber, a very big place on the Gulf of Tarentum, a villa at Cumae and another at Larinum,” he said eagerly, keen to impress her.

Servilia leaned back infinitesimally in her chair and exhaled very cautiously. He was rich. Extremely rich.

“How is your little boy?” he asked.

That obsession she could not conceal, it flamed behind her eyes and suffused her face with a passion that sat ill upon her naturally enigmatic features. “He misses his father, but I think he understands.”

Decimus Junius Silanus rose to his feet. “It is time I went, Servilia. May I come again?”

Her creamy lids fell over her eyes, the black lashes fanning upon her cheeks. A faint pink came into them, a faint smile turned up the corners of her little folded mouth. “Please do, Decimus Junius. It would please me greatly,” she said.