ABSOLVO The term employed by a jury when voting for the acquittal of the accused. It was used in the courts, not in the Assemblies.

aedile There were four Roman magistrates called aediles; two were plebeian aediles, two were curule aediles. Their duties were confined to the city of Rome. The plebeian aediles were created first (in 494 B.C.) to assist the tribunes of the plebs in their duties, but, more particularly, to guard the rights of the Plebs to their headquarters, the temple of Ceres in the Forum Boarium. The plebeian aediles soon inherited supervision of the city’s buildings as a whole, as well as archival custody of all plebiscites passed in the Plebeian Assembly, together with any senatorial decrees (consulta) directing the passage of plebiscites. They were elected by the Plebeian Assembly. Then in 367 B.C. two curule aediles were created to give the patricians a share in custody of public buildings and archives; they were elected by the Assembly of the People. Very soon, however, the curule aediles were as likely to be plebeians by status as patricians. From the third century B.C. downward, all four were responsible for the care of Rome’s streets, water supply, drains and sewers, traffic, public buildings, monuments and facilities, markets, weights and measures (standard sets of these were housed in the basement of the temple of Castor and Pollux), games, and the public grain supply. They had the power to fine citizens and non—citizens alike for infringements of any regulation appertaining to any of the above, and deposited the moneys in their coffers to help fund the games. Aedile—plebeian or curule—was not a part of the cursus honorum, but because of its association with the games was a valuable magistracy for a man to hold just before he stood for office as praetor.

Aeneas Prince of Dardania, in the Troad. He was the son of King Anchises and the goddess Aphrodite (Venus to the Romans). When Troy (Ilium to the Romans) fell to the forces of Agamemnon, Aeneas fled the burning city with his aged father perched upon his shoulder and the Palladium under one arm. After many adventures, he arrived in Latium and founded the race from whom true Romans implicitly believed they were descended. His son, variously called Ascanius or Iulus , was the direct ancestor of the Julian family.

aether That part of the upper atmosphere permeated by godly forces, or the air immediately around a god. It also meant the sky, particularly the blue sky of daylight.

Ager Gallicus Literally, Gallic land. The exact location and dimensions of the Ager Gallicus are not known, but it lay on the Adriatic shores of Italy partially within peninsular Italy and partially within Italian Gaul. Its southern border was possibly the Aesis River, its northern border not far beyond Ariminum. Originally the home of the Gallic tribe of Senones who settled there after the invasion of the first King Brennus in 390 B.C., it came into the Roman ager publicus when Rome took control of that part of Italy. It was distributed in 232 B.C. by Gaius Flaminius, and passed out of Roman public ownership.

ager publicus Land vested in Roman public ownership, most of it acquired by right of conquest or confiscated from its original owners as a punishment for disloyalty. This latter was particularly common within Italy itself. Roman ager publicus existed in every overseas province, in Italian Gaul, and inside the Italian peninsula. Responsibility for its disposal (usually in the form of large leaseholds) lay in the purlieus of the censors, though much of the foreign ager publicus lay unused.

Agger An agger was a double rampart bearing formidable fortifications. The Agger was a part of Rome’s Servian Walls, and protected the city on its most vulnerable side, the Campus Esquilinus.

agora The open space, usually surrounded by colonnades or some kind of public buildings, which served any Greek or Hellenic city as its public meeting place and civic center. The ,Roman equivalent was a forum.

Ague The old name for the rigors of malaria.

Allies Any nation or people or individual formally invested with the title “Friend and Ally of the Roman People’’ was an Ally. The term usually carried with it certain privileges in trade, commerce and political activities. (See also Italian Allies, socii).

AMOR Literally, “love.” Because it is “Roma” spelled backward, the Romans of the Republic commonly believed it was Rome’s vital secret name, never to be uttered aloud in that context.

Anatolia Roughly, modern Asian Turkey. It incorporated the ancient regions of Bithynia, Mysia, Asia Province, Phrygia, Pisidia, Pamphylia, Cilicia, Paphlagonia, Galatia, Pontus, Cappadocia, and Armenia Parva.

Ancus Marcius The fourth King of Rome, claimed by the family Marcius (particularly that branch cognominated Rex) as its founder—ancestor; unlikely, since the Marcii were plebeians. Ancus Marcius is said to have colonized Ostia, though there is some doubt as to whether he did this, or whether he took the salt pits at the mouth of the Tiber from their Etruscan owners by force of arms. Rome under his rule flourished. His one lasting public work was the building of the Wooden Bridge, the Pons Sublicius. He died in 617 B.C., leaving sons who did not inherit the throne—a source of later trouble.

animus The Oxford Latin Dictionary has the best definition, so I will quote it: “The mind as opposed to the body, the mind or soul as constituting with the body the whole person.” There are further definitions, but this one is pertinent to the way animus is used herein. One must be careful, however, not to attribute belief in the immortality of the soul to Romans.

arcade A long line of shops on both sides of a narrow walkway within a roofed building. The Covered Bazaar in Istanbul is probably very like (if much larger than) an ancient arcade.

Armenia Magna In ancient times, Armenia Magna extended from the southern Caucasus to the Araxes River, east to the corner of the Caspian Sea, and west to the sources of the Euphrates. It was immensely mountainous and very cold.

Armenia Parva Though called Little Armenia, this small land occupying the rugged and mountainous regions of the upper Euphrates and Arsanius Rivers was not a part of the Kingdom of Armenia. Until taken over by the sixth King Mithridates of Pontus, it was ruled by its own royal house, but always owed allegiance to Pontus, rather than to Armenia proper.

armillae The wide bracelets, of gold or of silver, awarded as prizes for valor to Roman legionaries, centurions, cadets and military tribunes of more junior rank.

Arvernian Pertaining to the Gallic tribe Arverni, who occupied lands in and around the northern half of the central massif of the Cebenna, in Gaul-across-the-Alps.

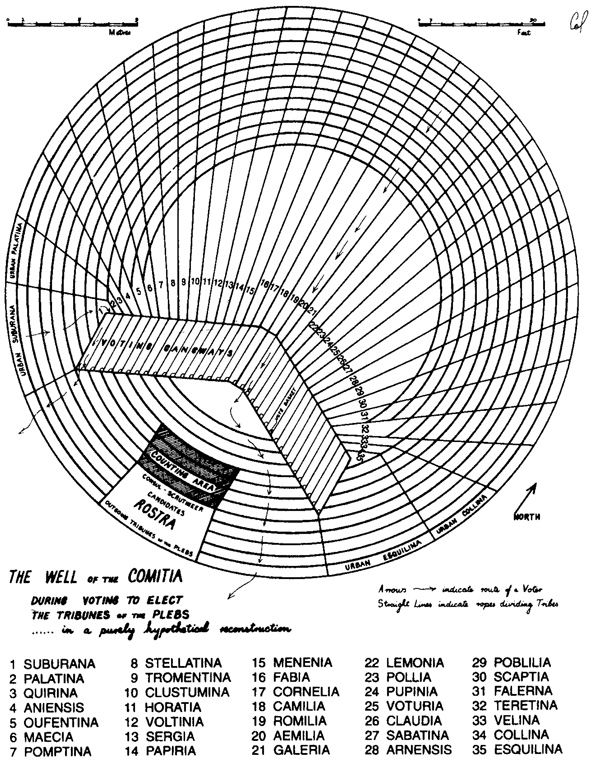

Assembly (comitia) Any gathering of the Roman People convoked to deal with governmental, legislative, judicial, or electoral matters. In the time of Sulla there were three true Assemblies—the Centuries, the People, and the Plebs. The Centuriate Assembly marshaled the People, patrician and plebeian, in their Classes, which were filled by a means test and were economic in nature. As this was originally a military assemblage, each Class gathered in the form of Centuries (which, excepting for the eighteen senior Centuries, by the time of Sulla numbered far in excess of one hundred men per century, as it had been decided to limit the number of Centuries). The Centuriate Assembly met to elect consuls, praetors, and (every five years usually) censors. It also met to hear charges of major treason (perduellio),and could pass laws. Because of its originally military nature, the Centuriate Assembly was obliged to meet outside the pomerium, and normally did so on the Campus Martius at a place called the saepta. It was not usually convoked to pass laws or hear trials. The Assembly of the People (comitia populi tributa) allowed the full participation of patricians, and was tribal in nature. It was convoked in the thirty-five tribes into which all Roman citizens were placed. Called together by a consul or praetor, it normally met in the lower Forum Romanum, in the Well of the Comitia. It elected the curule aediles, the quaestors, and the tribunes of the soldiers. It could formulate and pass laws, and conduct trials until Sulla established his standing courts.The Plebeian Assembly (comitia plebis tributa or concilium plebis) met in the thirty-five tribes, but did not allow the participation of patricians. The only magistrate empowered to convoke it was the tribune of the plebs. It had the right to enact laws (strictly, plebiscites) and conduct trials, though thelatter more or less disappeared after Sulla established his standing courts. Its members elected the plebeian aediles and the tribunes of the plebs. The normal place for its assemblage was in the Well of the Comitia. (See also voting and tribe.)

atrium The main reception room of a Roman domus, or private house. It mostly contained an opening in the roof (the compluvium) above a pool (the impluvium) originally intended as a water reservoir for domestic use. By the time of the late Republic, the pool had become ornamental only.

auctoritas A very difficult Latin term to translate, as it meant far more than the English word “authority” implies. It carried nuances of pre-eminence, clout, public importance and—above all—the ability to influence events through sheer public reputation. All the magistracies possessed auctoritas as an intrinsic part of their nature, but auctoritas was not confined to those who held magistracies; the Princeps Senatus, Pontifex Maximus, other priests and augurs, consulars, and even some private individuals outside the ranks of the Senate also owned auctoritas. Though the King of the Backbenchers, Publius Cornelius Cethegus, never held a magistracy, his auctoritas was formidable.

augur A priest whose duties concerned divination. He and his fellow augurs comprised the College of Augurs, an official State body which had numbered twelve members (usually six patricians and six plebeians) until in 81 B.C. Sulla increased it to fifteen members, always intended thereafter to contain at least one more plebeian than patrician. Originally augurs were co-opted by their fellow augurs, but in 104 B.C. Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus brought in a law compelling election of future augurs by an assembly of seventeen tribes chosen from the thirty-five by lot. Sulla removed election in 81 B.C., going back to co-optation. The augur did not predict the future, nor did he pursue his auguries at his own whim; he inspected the proper objects or signs to ascertain whether or not the projected undertaking was one meeting with the approval of the gods, be the undertaking a contio (q.v.), a war, a new law, or any other State business, including elections. There was a standard manual of interpretation to which the augur referred: augurs “went by the book.” The augur wore the toga trabea (see that entry), and carried a curved staff called the lituus.

auxiliary A legion of non—citizens incorporated into a Roman army was called an auxiliary legion; its soldiers were also known as auxiliaries, and the term extended to cover cavalry units as well. By the time of Sulla’s dictatorship, auxiliary infantry had more or less disappeared, whereas auxiliary cavalry was still very much in evidence.

Bacchic Pertaining to the god Bacchus (in Greek, Dionysos), who was the patron of wine, and therefore by extension the patron of carousing. During the early and middle Republic excesses of a Bacchic nature were frowned upon, and even legislated against; by the time of Sulla, however, some degree of tolerance had crept in.

barbarian Derived from a Greek word having strong onomatopoeic overtones; on first hearing these peoples speak, the Greeks thought they sounded “bar—bar,” like animals barking. It was not a word used to describe any people settled around the Mediterranean Sea, but referred to races and nations deemed uncivilized, lacking in an admirable or desirable culture. Gauls, Germans, Scythians, Sarmatians and other peoples of the Steppes were considered barbarian.

basilica A large building devoted to public activities such as courts of law, and also to commercial activities in shops and offices. The basilica was two—storeyed and clerestory—lit, and incorporated an arcade of shops under what we might call verandah extensions along either length side. Though the aediles looked after these buildings once erected, their actual building was undertaken at the expense of a prominent Roman nobleman. The first basilica was put up by Cato the Censor on the Clivus Argentarius next door to the Senate House, and was known as the Basilica Porcia; as well as accommodating banking institutions, it was also the headquarters of the College of the Tribunes of the Plebs. At the time of this book, there also existed the Basilica Aemilia, the Basilica Sempronia, and the Basilica Opimia, all on the borders of the lower Forum Romanum.

Bellona The Italian goddess of war. Her temple lay outside the pomerium of Rome on the Campus Martius, and was vowed in 296 B.C. by the great Appius Claudius Caecus. A group of special priests called fetiales conducted her rituals. A large vacant piece of land lay in front of the temple, known as Enemy Territory.

bireme A ship constructed for use in naval warfare, and intended to be rowed rather than sailed (though it was equipped with a mast and sail, usually left ashore if action was likely). Some biremes were decked or partially decked, but most were open. It seems likely that the oarsmen did sit in two levels at two banks of oars, the upper bank and its oarsmen accommodated in an outrigger, and the lower bank’s oars poking through ports in the galley’s sides. Built of fir or another lightweight pine, the bireme could be manned only in fair weather, and fight battles only in very calm seas. It was much longer than it was wide in the beam (the ratio was about 7:1), and probably averaged about 100 feet (30 meters) in length. Of oarsmen it carried upward of one hundred. A bronze—reinforced beak made of oak projected forward of the bow just below the waterline, and was used for ramming and sinking other vessels. The bireme was not designed to carry marines or grapple to engage other vessels in land—style combat. Throughout Greek, Republican Roman and Imperial Roman times, all ships were rowed by professional oarsmen, never by slaves. The slave oarsman was a product of Christian times. Boreas The north wind.

Brothers Gracchi See Gracchi.

caelum grave et pestilens Malaria.

Calabria Confusing for modern Italians! Nowadays Calabria is the toe of the boot, but in ancient times Calabria was the heel. Brundisium was its most important city, followed by Tarentum. Its people were the Illyrian Messapii.

Campus Esquilinus The area of flattish ground outside the Servian Walls and the double rampart of the Agger. It lay between the Porta Querquetulana and the Colline Gate, and was the site of Rome’s necropolis.

Campus Lanatarius An area of flattish ground inside the Servian Walls on that part of the Aventine adjacent to the walls. It lay between the Porta Raudusculana and the Porta Naevia. Here were extensive stockyards and slaughtering yards.

Campus Martius The Field of Mars. Situated north of the Servian Walls, the Campus Martius was bounded by the Capitol on its south and the Pincian Hill on its east; the rest of it was enclosed by a huge bend in the Tiber River. In Republican times it was not inhabited as a suburb, but was the place where triumphing armies bivouacked, the young were trained in military exercises, horses engaged in chariot racing were stabled and trained, the Centuriate Assembly met, and market gardening vied with public parklands. At the apex of the river bend lay the public swimming holes called the Trigarium, and just to the north of the Trigarium were medicinal hot springs called the Tarentum. The Via Lata (Via Flaminia) crossed the Campus Martius on its way to the Mulvian Bridge, and the Via Recta bisected it at right angles to the Via Lata. Capena Gate The Porta Capena. One of Rome’s two most important gates in the Servian Walls (the other was the Porta Collina, the Colline Gate). It lay beyond the Circus Maximus, and outside it was the common highway which branched into the Via Appia and the Via Latina about half a mile from the gate.

capite censi Literally, the Head Count. See that entry.

career A dungeon. The other name for the Tullianum was simply Career.

Carinae One of Rome’s more exclusive addresses. Incorporating the Fagutal, the Carinae was the northern tip of the Oppian Mount on its western side; it extended between the Velia and the Clivus Pullius. Its outlook was southwestern, across the swamps of the Palus Ceroliae toward the Aventine.

cartouche The personal hieroglyphs peculiar to each individual Pharaoh of Egypt, enclosed within an oval (or rectangular with rounded corners) framing line. The practice continued through to rulers of the Ptolemaic dynasty.

Cassiterides The Tin Isles. Now known as the Scilly Isles, off the southwestern tip of Cornwall, England. The tin mined in Cornwall was shipped to the Cassiterides, which was used as a way station. Crassus’s father voyaged there in 95 B.C.

Castor The never—forgotten Heavenly Twin. Though the imposing temple in the Forum Romanum was properly the temple of Castor and Pollux (also called the Dioscuri), it was always referred to by Romans as Castor’s. This led to many jokes about dual enterprises in which one of the two prime movers was consistently overlooked. Religiously, Castor and Pollux were among the principal deities worshipped by Romans, perhaps because, like Romulus and Remus, they were twins.

cavalry Horse—mounted soldiers. By the time of the late Republic, all cavalry incorporated into Roman armies was auxiliary in nature: that is, composed of non—citizens. Germans, Gauls, Thracians, Galatians and Numidians commonly formed Roman cavalry units, as these were all peoples numbering horse—riding tribes among them. There seems at most times to have been adequate volunteers to fill cavalry ranks; Gauls and Numidians apparently were the most numerous. The cavalry was formed into regiments of five hundred horsemen, each regiment divided into ten squadrons of fifty troopers. They were led by officers of their own nationality, but the overall commander of cavalry was always Roman.

cavea See the entry on theaters.

cella A room without a specific name (or function, in domestic dwellings). A temple room was always just a cella.

Celtiberian The general term covering the tribes inhabiting northern and north—central Spain. As the name suggests, racially they were an admixture of migratory Celts from Gaul and the more ancient indigenous Iberian stock. Their towns were almost all erected upon easily fortified crags, hills or rocky outcrops, and they were past masters at guerrilla warfare.

censor The censor was the most august of all Roman magistrates, though he lacked imperium and was therefore not entitled to be escorted by lictors. Two censors were elected by the Centuriate Assembly to serve for a period of five years (called a lustrum); censorial activity was, however, mostly limited to the first eighteen months of the lustrum, which was ushered in by a special sacrifice, the suovetaurilia, of pig, sheep and ox. No man could stand for censor unless he had been consul first, and usually only those consulars of notable auctoritas and dignitas bothered to stand. The censors inspected and regulated membership in the Senate and the Ordo Equester, and conducted a general census of Roman citizens throughout the Roman world. They had the power to transfer a citizen from one tribe to another as well as one Class to another. They applied the means test. The letting of State contracts for everything from the farming of taxes to public works was also their responsibility. In 81 B.C. Sulla abolished the office, apparently as a temporary measure.

census Every five years the censors brought the roll of the citizens of Rome up to date. The name of every Roman citizen male was entered on these rolls, together with informationabout his tribe, his economic class, his property and means, and his family. Neither women nor children were formally registered as being Roman citizens, though there are cases documented in the ancient sources that clearly show some women awarded the Roman citizenship in their own right. The city of Rome’s census was taken on the Campus Martius at a special station erected for the purpose; those living elsewhere in Italy had to report to the authorities at the nearest municipal registry, and those living abroad to the provincial governor. There is some evidence, however, that the censors of 97 B.C., Lucius Valerius Flaccus and Marcus Antonius Orator, changed the manner in which citizens living outside Rome but inside Italy proper were enrolled.

centunculus A coat or quilt made out of patches in many colors.

Centuriate Assembly See the entry under Assembly.

centurion The regular professional officer of both Roman citizen and auxiliary infantry legions. It is a mistake to equate him with the modern noncommissioned officer; centurions enjoyed a relatively exalted status uncomplicated by modern social distinctions. A defeated Roman general hardly turned a hair if he lost even senior military tribunes, but tore his hair out in clumps if he lost centurions. Centurion rank was graduated; the most junior commanded an ordinary century of eighty legionaries and twenty noncombatant assistants, but exactly how he progressed in what was apparently a complex chain of progressive seniority is not known. In the Republican army as reorganized by Gaius Marius, each cohort had six centuriones (singular, centurio), with the most senior man, the pilus prior, commanding the senior century of his cohort as well as the entire cohort. The ten men commanding the ten cohorts which made up a full legion were also ranked in seniority, with the legion’s most senior centurion, the primus pilus (this term was later reduced to primipilus), answering only to his legion’s commander (either one of the elected tribunes of the soldiers, or one of the general’s legates). During Republican times promotion to centurion was up from the ranks. The centurion had certain easily recognizable badges of office: he wore greaves on his shins, a shirt of scales rather than chain links, a helmet crest projecting sideways rather than front—to—back, and carried a stout knobkerrie of vine wood. He also wore many decorations.

century Any grouping of one hundred men. Most importantly, the Roman legion was organized in basic units of one hundred men called centuries. The Classes of the Centuriate Assembly were also organized in centuries, but with steadily increasing population these centuries came eventually to contain far more than one hundred men. chlamys The cloaklike outer garment worn b^ Greek men.

chryselephantine A work of art fashioned in gold and ivory.

chthonic Pertaining to the Underworld, and ill—omened.

Cimbri A Germanic people originally inhabiting the upper or northern half of the Jutland peninsula (modern Denmark). Strabo says that a sea—flood drove them out in search of a new homeland about 120 B.C. In combination with the Teutones and a mixed group of Germans and Celts (the Marcomanni—Cherusci—Tigurini) they wandered Europe in search of this homeland until they ran foul of Rome. In 102 and 101 B.C. Gaius Marius utterly defeated them, and the migration disintegrated.

Circus Flaminius The circus situated on the Campus Martius not far from the Tiber and the Forum Holitorium. It was built in 221 B.C., and sometimes served as a place for a comitial meeting, when the Plebs or the People had to meet outside the pomerium. It seems to have been well used as a venue for the games, but for events pulling in smaller attendances than the Circus Maximus. It held about fifty thousand spectators.

Circus Maximus The old circus built by King Tarquinius Priscus before the Republic began. It filled the whole of the Vallis Murcia, a declivity between the Palatine and Aventine Mounts. Even though its capacity was about one hundred and fifty thousand spectators, there is ample evidence that during Republican times freedman citizens were classified as slaves when it came to admission to the Circus Maximus, and were thus denied. Just too many people wanted to go to the circus games. Women were permitted to sit with men.

citizenship For the purposes of this series of books, the Roman citizenship. Possession of it entitled a man to vote in his tribe and his Class (if he was economically qualified to belong to a Class) in all Roman elections. He could not be flogged, he was entitled to the Roman trial process, and he had the right of appeal. The male citizen became liable for military service on his seventeenth birthday. After the lex Minicia of 91 B.C., the child of a union between a Roman citizen of either sex and a non—Roman was forced to assume the citizenship of the non—Roman parent.

citocacia A mild Latin profanity, meaning “stinkweed.”

citrus wood The most prized cabinet wood of the Roman world. It was cut from vast galls on the root system of a cypresslike tree, Callitris quadrivavis vent., which grew in the highlands of North Africa all the way from the Oasis of Ammonium and Cyrenaica to the far Atlas of Mauretania. Though termed citrus, the tree was not botanically related to orange or lemon. Most citrus wood was reserved for making tabletops (usually mounted upon a single chryselephantine pedestal), but it was also turned as bowls. No tabletops have survived to modern times, but enough bowls have for us to see that citrus wood was certainly the most beautiful timber of all time.

Classes These were five in number, and represented the economic divisions of property—owning or steady—income—earning Roman citizens. The members of the First Class were the richest, the members of the Fifth Class the poorest. Those Roman citizens who belonged to the capite censi, or Head Count, were too poor to qualify for a Class status, and so could not vote in the Centuriate Assembly. In actual fact, it was rare for the Third Class to be called upon to vote in the Centuriate Assembly, let alone members of the Fourth or Fifth Class!

client In Latin, cliens. The term denoted a man of free or freed status (he did not have to be a Roman citizen) who pledged himself to a man he called his patron. In the most solemn and binding way, the client undertook to serve the interests and obey the wishes of his patron. In return he received certain favors—usually gifts of money, or a job, or legal assistance. The freed slave was automatically the client of his ex-master until discharged of this obligation—if he ever was. A kind of honor system governed the client’s conduct in relation to his patron, and was adhered to with remarkable consistency. To be a client did not necessarily mean that a man could not also be a patron; more that he could not be an ultimate patron, as technically his own clients were also the clients of his patron. During the Republic there were no formal laws concerning the client—patron relationship because they were not necessary—no man, client or patron, could hope to succeed in life were he known as dishonorable in this vital function. However, there were laws regulating the foreign client—patron relationship; foreign states or client—kings acknowledging Rome as patron were legally obliged to find the ransom for any Roman citizen kidnapped in their territories, a fact that pirates relied on heavily for an additional source of income. Thus, not only individuals could become clients; whole towns and even countries often were.

client—king A foreign monarch might pledge himself as a client in the service of Rome as his patron, thereby entitling his kingdom to be known as a Friend and Ally of the Roman People. Sometimes, however, a foreign monarch pledged himself as the client of a Roman individual, as did certain rulers to Lucullus and Pompey.

clivus A hilly street.

cognomen The last name of a Roman male anxious to distinguish himself from all his fellows possessed of an identical first ] and family [(nomen)] name. He might adopt one for himself, as did Pompey with the cognomen Magnus, or simply continue to bear a cognomen which had been in the family for generations, as did the Julians cognominated Caesar. In some families it became necessary to have more than one cognomen: for example, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius Cornelianus Scipio Nasica, who was the adopted son of Metellus Pius the Piglet. Quintus was his first name ‘, Caecilius his family name ; Metellus Pius were cognomina belonging to his adoptive father; Cornelianus indicated that he was by blood a Cornelian; and Scipio Nasica were the cognomina of his blood father. As things turned out, he was always known as Metellus Scipio, a neat compromise to both blood and adoptive family. The cognomen often pointed up some physical characteristic or idiosyncrasy—jug ears, flat feet, hump back, swollen legs—or else commemorated some great feat—as in the Caecilii Metelli who were cognominated Dalmaticus, Balearicus, Macedonicus, Numidicus, these being related to a country each man had conquered. The best cognomina were heavily sarcastic—Lepidus, meaning a thoroughly nice fellow, attached to a right bastard—or extremely witty—as with the already multiple—cognominated Gaius Julius Caesar Strabo Vopiscus, who earned an additional name, Sesquiculus, meaning he was more than just an arsehole, he was an arsehole and a half.

cohort The tactical unit of the legion. It comprised six centuries, and each legion owned ten cohorts. When discussing troop movements, it was more customary for the general to speak of his army in terms of cohorts than legions, which perhaps indicates that, at least until the time of Caesar, the general deployed or peeled off cohorts in battle. The maniple, formed of two centuries (there were three maniples to the cohort), ceased to have any tactical significance from the time of Marius.

college A body or society of men having something in common. Rome owned priestly colleges (such as the College of Pontifices), political colleges (as the College of Tribunes of the Plebs), civil colleges (as the College of Lictors), and trade colleges (for example, the Guild of Undertakers). Certain groups of men from all walks of life, including slaves, banded together in what were called crossroads colleges to look after the city of Rome’s major crossroads and conduct the annual feast of the crossroads, the Compitalia.

colonnade A roofed walkway flanked by one row of outer columns when attached to a building in the manner of a verandah, or, if freestanding (as a colonnade often was), by a row of columns on either side. comitia See the entry under Assembly. Comitia The large round well in which meetings of the comitia were held. It was located in the lower Forum Romanum adjacent to the steps of the Senate House and the Basilica Aemilia, and proceeded below ground level in a series of steps, forming tiers upon which men stood; comitial meetings were never conducted seated. When packed, the well could hold perhaps three thousand men. The rostra, or speaker’s platform, was grafted into one side.

CONDEMNO The word employed by a jury to deliver a verdict of “guilty.” It was a term confined to the courts; both courts and Assemblies had their own vocabularies.

confarreatio The oldest and strictest of the three forms of Roman marriage. By the time of Sulla, the practice of confarreatio was confined to patricians, and then was not mandatory. One of the chief reasons why confarreatio lost much popularity lay in the fact that the confarreatio bride passed from the hand of her father to the hand of her husband, and thus had far less freedom than women married in the usual way; she could not control her dowry or conduct business. The other main reason for the unpopularity of confarreatio lay in the extreme difficulty of dissolving it; divorce (diffarreatio) was so legally and religiously arduous that it was more trouble than it was worth unless the circumstances left no alternative.

Conscript Fathers When it was established by the Kings of Rome (traditionally by Numa Pompilius), the Senate consisted of one hundred patricians entitled patres—“fathers.” Then when plebeian senators were added during the first years of the Republic, they were said to be conscripti—“chosen without a choice.” Together, the patrician and plebeian members were said to be patres et conscripti; gradually the once—distinguishing terms were run together, and all members of the Senate were simply the Conscript Fathers.

consul The consul was the most senior Roman magistrate owning imperium, and the consulship (modern scholars do not refer to it as the “consulate” because a consulate is a modern diplomatic institution) was the top rung on the cursus honorum. Two consuls were elected each year by the Centuriate Assembly, and served for one year. They entered office on New Year’s Day (January 1). One was senior to the other; he was the one who had polled his requisite number of Centuries first. The senior consul held the fasces (q.v.) for the month of January, which meant his junior colleague looked on. In February the junior consul held the fasces, and they alternated month by month throughout the year. Both consuls were escorted by twelve lictors, but only the lictors of the consul holding the fasces that month shouldered the actual fasces as they preceded him wherever he went. By the last century of the Republic, a patrician or a plebeian could be consul, though never two patricians together. The proper age for a consul was forty-two, twelve years after entering the Senate at thirty, though there is convincing evidence that Sulla in 81 B.C. accorded patrician senators the privilege of standing for consul two years ahead of any plebeian, which meant the patrician could be consul at forty years of age. A consul’s imperium knew no bounds; it operated not only in Rome and Italy, but throughout the provinces as well, and overrode the imperium of a proconsular governor. The consul could command any army.

consular The name given to a man after he had been consul. He was held in special esteem by the rest of the Senate, and until Sulla became dictator was always asked to speak or give his opinion in the House ahead of the praetors, consuls—elect, etc. Sulla changed that, preferring to exalt magistrates in office and those elected to coming office. The consular, however, might at any time be sent to govern a province should the Senate require the duty of him. He might also be asked to take on other duties, like caring for the grain supply.

consultum The term for a senatorial decree, though it was expressed more properly as a senatus consultant. It did not have the force of law. In order to become law, a consultant had to be presented by the Senate to any of the Assemblies, tribal or centuriate, which then voted it into law—if the members of the Assembly requested felt like voting it into law. Sulla’s reformations included a law that no Assembly could legislate a bill unless it was accompanied by a senatus consultum. However, many senatorial consulta (plural) were never submitted to any Assembly, therefore were never voted into law, yet were accepted as laws by all of Rome; among these consulta were decisions about provincial governors, declaration and conduct of wars, and all to do with foreign affairs. Sulla in 81 B.C. gave these senatorial decrees the formal status of laws.

contio This was a preliminary meeting of a comitial Assembly in order to discuss the promulgation of a projected law, or any other comitial business. All three Assemblies were required to debate a measure in contio, which, though no voting took place, had nonetheless to be convoked by the magistrate empowered.

contubernalis A military cadet: a subaltern of lowest rank and age in the hierarchy of Roman military officers, but excluding the centurions. No centurion was ever a cadet, he was an experienced soldier.

corona civica Rome’s second—highest military decoration. A crown or chaplet made of oak leaves, it was awarded to a man who had saved the lives of fellow soldiers and held the ground on which he did this for the rest of the duration of a battle. It could not be awarded unless the saved soldiers swore a formal oath before their general that they spoke the truth about the circumstances. L. R. Taylor argues that among Sulla’s constitutional reforms was one relating to the winners of major military crowns; that, following the tradition of Marcus Fabius Buteo, he promoted these men to membership in the Senate, which answers the vexed question of Caesar’s senatorial status (complicated as it was by the fact that, while flamen Dialis, he had been a member of the Senate from the time he put on the toga virilis). Gelzer agreed with her—but, alas, only in a footnote.

corona graminea or obsidionalis Rome’s highest military decoration. Made of grass (or sometimes a cereal such as wheat, if the battle took place in a field of grain) taken from the battlefield and awarded “on the spot,” the Grass Crown conferred virtual immortality on a man, for it had been won on very few occasions during the Republic. The man who won it had to have saved a whole legion or army by his personal efforts. Both Quintus Sertorius and Sulla were awarded Grass Crowns.

cubit A Greek and Asian measurement of length not popular among Romans; it was normally held to be the distance between a man’s elbow and the tips of his fingers, and was probably about 18 inches (450mm).

cuirass Armor encasing a man’s upper body without having the form of a shirt. It consisted of two plates of bronze, steel, or hardened leather, the front one protecting thorax and abdomen, the other the back from shoulders to lumbar spine. The plates were held together by straps or hinges at the shoulders and along each side under the arms. Some cuirasses were exquisitely tailored to the contours of an individual’s torso, while others fitted any man of a particular size and physique. The men of highest rank—generals and legates—wore cuirasses tooled in high relief and silver—plated (sometimes, though rarely, gold—plated). Presumably as an indication of imperium, the general and perhaps the most senior of his legates wore a thin red sash around the cuirass about halfway between the nipples and waist; the sash was ritual1^ knotted and looped.

cultarius Scullard’s spelling: the O.L.D. prefers cultrarius. He was a public servant attached to religious duties, and his only job appears to have been to cut the sacrificial victim’s throat. However, in Republican Rome this was undoubtedly a full—time job for several men, so many were the ceremonies requiring sacrifice of an animal victim. He probably also helped dispose of the victim and was custodian of his tools. cunnus An extremely offensive Latin profanity—“cunt.” Cuppedenis Markets Specialized markets lying behind the upper Forum Romanum on its eastern side, between the Clivus Orbius and the Carinae/Fagutal. In it were vended luxury items like pepper, spices, incense, ointments and unguents and balms; it also served as the flower market, where a Roman (all Romans loved flowers) could buy anything from a bouquet to a garland to go round the neck or a wreath to go on the head. Until sold to finance Sulla’s campaign against King Mithridates, the actual land belonged to the State.

Curia Hostilia The Senate House. It was thought to have been built by the shadowy third king of Rome, Tullus Hostilius, hence its name: “the meeting—house of Hostilius.”

cursus honorum See the entry on magistrates.

curule chair The sella curulis was the ivory chair reserved exclusively for magistrates owning imperium: at first I thought only the curule aedile sat in one, but it seems that at some stage during the evolution of the Republic, imperium (and therefore the curule chair) was also conferred upon the two plebeian aediles. Beautifully carved in ivory, the chair itself had curved legs crossing in a broad X, so that it could be folded up. It was equipped with low arms, but had no back.

DAMNO The word employed by a comitial Assembly to indicate a verdict of “guilty.” It was not used in the courts, perhaps because the courts did not have the power to execute a death penalty.

decury A group of ten men. The tidy—minded Romans tended to subdivide groups containing several hundred men into tens for convenience in administration and direction. Thus the Senate was organized in decuries (with a patrician senator as the head of each decury), the College of Lictors, and probably all the other colleges of specialized public servants as well. It has been suggested that the legionary century was also divided into decuries, ten men messing together and sharing a tent, but evidence points more to eight soldiers. As a legionary century contained eighty soldiers, not one hundred, this would give ten groups of eight soldiers. But perhaps each eight legionaries were given two of the century’s twenty noncombatants as servants and general factotums, thus bringing each octet up to a decury.

demagogue Originally a Greek concept, the demagogue was a politician whose chief appeal was to the crowds. The Roman demagogue (almost inevitably a tribune of the plebs) preferred the arena of the Comitia well to the Senate House, but it was no part of his policy to “liberate the masses,” nor on the whole were those who flocked to listen to him composed of the very lowly. The term simply indicated a man of radical rather than ultra-conservative bent.

denarius Plural, denarii. Save for a very rare issue or two of gold coins, the denarius was the largest denomination of coin under the Republic. Of pure silver, it contained about 3.5 grams of the metal, and was about the size of a dime—very small. There were 6,250 denarii to one silver talent. Of actual coins in circulation, there were probably more denarii than sesterces.

diadem This was not a crown or a tiara, but simply a thick white ribbon about one inch (25mm) wide, each end embroidered and often finished with a fringe. It was the symbol of the Hellenic sovereign; only King and/or Queen could wear it. The coins show that it was worn either across the forehead or behind the hairline, and was knotted at the back below the occiput; the two ends trailed down onto the shoulders.

dies religiosi Days of the year regarded as ill-omened. On them nothing new ought to be done, nor religious ceremonies conducted. Some dies religiosi commemorated defeats in battle, on three dies religiosi the mundus (underworld gate) was left open, on others certain temples were closed, on yet others the hearth of Vesta was left open. The days after the Kalends, Nones and Ides of each month were dies religiosi, and thought so ill-omened that they had a special name: Black Days.

diffarreatio See the entry on confarreatio.

dignitas Like auctoritas (q.v.), the Latin dignitas has connotations not conveyed by the English word derived from it, “dignity.” It was a man’s personal standing in the Roman world rather than his public standing, though his public standing was enormously enhanced by great dignitas. It gave the sum total of his integrity, pride, family and ancestors, word, intelligence, deeds, ability, knowledge, and worth as a man. Of all the assets a Roman nobleman possessed, dignitas was likely to be the one he was most touchy about, and protective of. I have elected to leave the term untranslated in my text.

diverticulum In the two earlier books, I used this term to mean only the “ring roads” around the city of Rome that linked all the arterial roads together. In Fortune’s Favorites it is also used to indicate sections where an arterial road bifurcated to connect with important towns not serviced by the arterial road itself, then fused together again, as with the two diverticula on the Via Flaminia which must have already existed by the late Republic, though not generally conceded to exist until imperial times. Did the diverticulum to Spoletium not exist, for example, neither Carrinas nor Pompey would have been able to fetch up there so quickly.

divinatio Literally, guesswork. This was a special hearing by a specially appointed panel of judges to determine the fitness of a man to prosecute another man. It was not called into effect unless a man’s fitness was challenged by the defense. The name referred to the fact that the panel of judges arrived at a decision without the presentation of hard evidence—that is, they arrived at a conclusion by guesswork.

doctor The man who was responsible for the training and physical fitness of gladiators.

drachma The” name I have elected to use when speaking of Hellenic currency rather than Roman, because the drachma most closely approximated the denarius in weight at around 4 grams. Rome, however, was winning the currency race because of the central and uniform nature of Roman coins; during the late Republic, the world was beginning to prefer to use Roman coins rather than Hellenic.

Ecastor! Edepol! The most genteel and inoffensive of Roman exclamations of surprise or amazement, roughly akin to “Gee!” or “Wow!” Women used “Ecastor!” and men “Edepol!” The roots suggest they invoked Castor and Pollux.

electrum An alloy of gold and silver. In times dating back to before the Republic electrum was thought to be a metal in itself, and like the electrum rod in the temple of Jupiter Feretrius on the Capitol, it was left as electrum. By the time of the Republic, however, it was known to be an alloy, and was separated into its gold and silver components by cementationwith salt, or treatment with a metallic sulphide.

Epicurean Pertaining to the philosophical system of the Greek Epicurus. Originally Epicurus had advocated a kind of hedonism so exquisitely refined that it approached asceticism on its left hand, so to speak; a man’s pleasures were best sampled one at a time, and strung out with such relish that any excess defeated the exercise. Public life or any other stressful work was forbidden. These tenets underwent considerable modification in Rome, so that a Roman nobleman could call himself an Epicure yet still espouse his public career. By the late Republic, the chief pleasure of an Epicurean was food.

epulones A minor order of priests whose business was to organize senatorial banquets after festivals of Jupiter Optimus Maximus, and also to arrange the public banquets during games and some feast days.

equestrian Pertaining to the knights.

ethnarch The general Greek word for a city or town magistrate. There were other and more specific names in use, but I do not think it necessary to compound confusion in readers by employing a more varied terminology.

Euxine Sea The modern Black Sea. Because of the enormous number of major rivers which flowed into it (especially in times before water volume was regulated by dams), the Euxine Sea contained less salt than other seas; the current through Thracian Bosporus and Hellespont always flowed from the Euxine toward the Mediterranean (the Aegean)—which made it easy to quit the Euxine, but hard to enter it.

exeunt omnes Literally, “Everybody leave!” It has been a stage direction employed by playwrights since drama first came into being.

faction The following of a Roman politician is best described as a faction; in no way could a man’s followers be described as a political party in the modern sense. Factions formed around men owning auctoritas and dignitas, and were purely evidence of that individual’s ability to attract and hold followers. Political ideologies did not exist, nor did party lines. For that reason I have avoided (and will continue to avoid) the terms Optimate and Popularis, as they give a false impression of Roman political solidarity to a party—acclimatized modern reader.

Faesulae Modern Fiesole. Possibly because it was settled by the Etruscans before Rome became a power, it was always deemed a part of Etruria; in actual fact it lay north of the Arnus River, in what was officially Italian Gaul.

fasces The fasces were bundles of birch rods ritually tied together in a crisscross pattern by red leather thongs. Originally an emblem of the Etruscan kings, they passed into the customs of the emerging Rome, persisted in Roman life throughout the Republic, and on into the Empire. Carried by men called lictors (q.v.), they preceded the curule magistrate (and the propraetor and proconsul as well) as the outward symbol of his imperium. Within the pomerium only the rods went into the bundles, to signify that the curule magistrate had the power to chastise, but not to execute; outside the pomerium axes were inserted into the bundles, to signify that the curule magistrate or promagistrate did have the power to execute. The only man permitted to insert the axes into the midst of the rods inside the pomerium was the dictator. The number of fasces indicated the degree of imperium: a dictator had twenty-four, a consul and proconsul twelve, a praetor and propraetor six, and the aediles two. Sulla, incidentally, was the first dictator to be preceded by twenty-four lictors bearing twenty-four fasces; until then, dictators had used the same number as consuls, twelve.

fasti The fasti were originally days on which business could be transacted, but came to mean other things as well: the calendar, lists relating to holidays and festivals, and the list of consuls (this last probably because Romans preferred to reckon up their years by remembering who had been the consuls in any given year). The entry in the glossary to The First Man in Rome contains a fuller explanation of the calendar than space permits me here—under fasti, of course.

fellator Mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa! My fault entirely that in the two previous volumes of this series, I managed to give the man on the receiving end the wrong name! It does happen that one becomes confused, as I do by opposites, left and right, and clockwise versus anticlockwise. A cerebral aberration of sorts. The fact remains that I was wrong. The fellator was the man sucking the penis, the irrumator the man whose penis was being sucked. Fellator sucker, irrumator suckee.

feriae Holidays. Though attendance at public ceremonies on such holidays was not obligatory, feriae traditionally demanded that business, labor and lawsuits not be pursued, and that quarrels, even private ones, should be avoided. The rest from normal labors on feriae extended to slaves and also some animals, including oxen but excluding equines of all varieties. fetiales A special college of priests whose duties were to serve Bellona, the goddess of war. Though it was an honor to be appointed a fetialis, during the late Republic the rites of making war or peace as pertaining to Bellona were much neglected; it was Caesar’s great—nephew, Augustus, who brought the college back to full practice.

filibuster A modern word for a political activity at least as old as the Senate of Rome. It consisted, then as now, of “talking a motion out”: the filibusterer droned on and on about everything from his childhood to his funeral plans, thus preventing other men from speaking until the political danger had passed. And preventing the taking of a vote!

flamen The flamines (plural) were probably the oldest of Rome’s priests in time, dating back at least as far as the Kings. There were fifteen flamines, three major and twelve minor. The three major flaminates were Dialis (Jupiter Optimus Maxi—mus), Martialis (Mars), and Quirinalis (Quirinus). Save for the poor flamen Dialis—his nature is discussed fully in the text—none of the flamines seemed terribly hedged about with prohibitions or taboos, but all three major flamines qualified for a public salary, a State house, and membership in the Senate. The wife of the flamen was known as the flaminica. The flamen and flaminica Dialis had to be patrician in status, though I have not yet discovered whether this was true of the other flamines, major or minor. To be on the safe side, I elected to stay with patrician appointments.

Fortuna One of Rome’s most worshipped and important deities. Generally thought to be a female force, Fortuna had many different guises; Roman godhead was usually highly specific. Fortuna Primigenia was Jupiter’s firstborn, Fors Fortuna was of particular importance to the lowly, Fortuna Virilis helped women conceal their physical imperfections from men, Fortuna Virgo was worshipped by brides, Fortuna Equestris looked after the knights, and Fortuna Huiusque Diei (“the fortune of the present day”) was the special object of worship by military commanders and prominent politicians having military backgrounds. There were yet other Fortunae. The Romans believed implicitly in luck, though they did not regard luck quite as we do; a man made his luck, but was—even in the case of men as formidably intelligent as Sulla and Caesar—very careful about offending Fortuna, not to mention superstitious. To be favored by Fortuna was considered a vindication of all a man stood for.

forum The Roman meeting place, an open area surrounded by buildings, many of which were of a public nature. Forum Boarium The meat markets, situated at the starting—post end of the Circus Maximus, below the Germalus of the Palatine. The Great Altar of Hercules and several different temples to Hercules lay in the Forum Boarium, which was held to be peculiarly under his protection. Forum Holitorium The vegetable markets, situated on the bank of the Tiber athwart the Servian Walls between the river and the flank of the Capitoline Mount. There were three gates in the walls at the Forum Holitorium—the Porta Triumphalis (used only to permit the triumphal parade into the city), the Porta Carmentalis, and the Porta Flumentana. It is generally thought that the Servian Walls of the Forum Holitorium were crumbled away to nothing by the late Republic, but I do not believe this; the threat of the Germans alone caused many repairs to the Servian Walls.

Forum Romanum This long open space was the center of Roman public life, and was largely devoted, as were the buildings around it, to politics, the law, business, and religion. I do not believe that the free space of the Forum Romanum was choked with a permanent array of booths, stalls and barrows; the many descriptions of constant legal and political business in the lower half of the Forum would leave little room for such apparatus. There were two very large market areas on the Esquiline side of the Forum Romanum, just removed from the Forum itself by one barrier of buildings, and in these, no doubt, most freestanding stalls and booths were situated. Lower than the surrounding districts, the Forum was rather damp, cold, sunless—but very much alive in terms of public human activity.

freedman A manumitted slave. Though technically a free man (and, if his former master was a Roman citizen, himself a Roman citizen), the freedman remained in the patronage of his former master, who had first call on his time and services. He had little chance to exercise his vote in either of the two tribal Assemblies, as he was invariably placed into one of two vast urban tribes, Suburana or Esquilina. Some slaves of surpassing ability or ruthlessness, however, did amass great fortunes and power as freedmen, and could therefore be sure of a vote in the Centuriate Assembly; such freedmen usually managed to have themselves transferred into rural tribes as well, and thus exercised the complete franchise.

free man A man born free and never sold into outright slavery, though he could be sold as a nexus or debt slave. The latter was rare, however, inside Italy during the late Republic.

games In Latin, ludi. Games were a Roman institution and pastime which went back at least as far as the early Republic, and probably a lot further. At first they were celebrated only when a general triumphed, but in 336 B.C. the ludi Romani became an annual event, and were joined later by an ever—increasing number of other games throughout the year. All games tended to become longer in duration as well. At first games consisted mostly of chariot races, then gradually came to incorporate animal hunts, and plays performed in specially erected temporary theaters. Every set of games commenced on the first day with a solemn but spectacular religious procession through the Circus, after which came a chariot race or two, and then some boxing and wrestling, limited to this first day. The succeeding days were taken up with theatricals; comedy was more popular than tragedy, and eventually the freewheeling Atellan mimes and farces most popular of all. As the games drew to a close, chariot racing reigned supreme, with animal hunts to vary the program. Gladiatorial combats did not form a part of Republican games (they were put on by private individuals, usually in connection with a dead relative, in the Forum Romanum rather than in the Circus). Games were put on at the expense of the State, though men ambitious to make a name for themselves dug deeply into their private purses while serving as aediles to make “their” games more spectacular than the State—allocated funds permitted. Most of the big games were held in the Circus Maximus, some of the smaller ones in the Circus Flaminius. Free Roman citizen men and women were permitted to attend (there was no admission charge), with women segregated in the theater but not in the Circus; neither slaves nor freedmen were allowed admission, no doubt because even the Circus Maximus, which held 150,000 people, was not large enough to contain freedmen as well as free men.

Gaul, Gauls A Roman rarely if ever referred to a Celt as a Celt; he was known as a Gaul. Those parts of the world wherein Gauls lived were known as some kind of Gaul, even when the land was in Anatolia (Galatia). Before Caesar’s conquests, Gaul-across-the-Alps—that is, Gaul west of the Italian Alps—was roughly divided into two parts: Gallia Comata or Long-haired Gaul, neither Hellenized nor Romanized, and a coastal strip with a bulging extension up the valley of the river Rhodanus which was known as The Province, and both Hellenized as well as Romanized. The name Narbonese Gaul (which I have used in this book) did not become official until the principate of Augustus, though Gaul around the port of Narbo was probably always known as that. The proper name for Gaul-across-the-Alps was Transalpine Gaul. That Gaul more properly known as Cisalpine Gaul because it lay on the Italian side of the Alps I have elected to call Italian Gaul. It too was divided into two parts by the Padus River (the modern Po); I have called them Italian Gaul—across—the—Padus and Italian Gaul—this—side—of—the—Padus. There is also no doubt that the Gauls were racially closely akin to the Romans, for their languages were of similar kind, as were many of their technologies. What enriched the Roman at the ultimate expense of the Gaul was his centuries—long exposure to other Mediterranean cultures.

gens A man’s clan or extended family. It was indicated by his nomen, such as Cornelius or Julius, but was feminine in gender, hence they were the gens Cornelia and the gens Julia.

gig A two—wheeled vehicle drawn by either two or four animals, more usually mules than horses. Within the limitations of ancient vehicles—springs and shock absorbers did not exist—the gig was very lightly and flexibly built, and was the vehicle of choice for a Roman in a hurry because it was easy for a team to draw, therefore speedy. However, it was open to the elements. In Latin it was a cisia. The carpentum was a heavier version of the gig, having a closed coach body.

gladiator There is considerable wordage within the pages of this book about gladiators, so I will not enlarge upon them here. Suffice it to say that during Republican times there were only two kinds of gladiator, the Thracian and the Gaul, and that gladiatorial combat was not usually “to the death.” The thumbs—up, thumbs—down brutality of the Empire crowds did not exist, perhaps because the State did not own or keep gladiators under the Republic, and few of them were slaves; they were owned by private investors, and cost a great deal of money to acquire, train and maintain. Too much money to want them dead or maimed in the ring. Almost all gladiators during the Republic were Romans, usually deserters or mutineers from the legions. It was very much a voluntary occupation.

governor A very useful English term to describe the pro—magistrate—proconsul or propraetor—sent to direct, command and manage one of Rome’s provinces. His term was set at one year, but very often it was prorogued, sometimes (as in the case of Metellus Pius in Further Spain) for many years.

Gracchi The Brothers Gracchi, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus and his younger brother, Gaius Sempronius Gracchus. They were the sons of Cornelia (daughter of Scipio Africanus and Aemilia Paulla) and Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (consul in 177 and 163 B.C., censor in 169 B.C.), and the consulship, high military command and the censorship were thus their birthright. Neither man advanced beyond the tribunate of the plebs, due to a peculiar combination of high ideals, iconoclastic thinking, and a tremendous sense of duty to Rome. Tiberius Gracchus, a tribune of the plebs in 133 B.C., set out to right the wrongs he saw in the way the Roman State was administering its ager publicus; his aim was to give it to the civilian poor of Rome, thus encouraging them by dowering them with land to breed sons and work hard. When the end of the year saw his work still undone, Tiberius Gracchus flouted custom by attempting to run for the tribunate of the plebs a second time. He was clubbed to death on the Capitol. Gaius Gracchus, ten years Tiberius’s junior, was elected a tribune of the plebs in 123 B.C. More able than his brother, he had also profited from his mistakes, and bade fair to alter the whole direction of the ultra-conservative Rome of his time. His reforms were much wider than Tiberius’s, and embraced not only the ager publicus, but also cheap grain for the populace (a measure aimed not only at the poor, for he adopted no means test), regulation of service in the army, the founding of Roman citizen colonies abroad, public works throughout Italy, removal of the courts from the Senate, a new system to farm the taxes of Asia Province, and an enhancement of citizen status for Latins and Italians. When his year as a tribune of the plebs finished, Gaius Gracchus emulated his brother and ran for a second term. Instead of being killed for his presumption, he got in. At the end of his second term he determined to run yet again, but was defeated in the elections. Helpless to intervene, he had to see all his laws and reforms begin to topple. Prevented from availing himself of peaceful means, Gaius Gracchus resorted to violence. Many of his partisans were killed when the Senate passed its first—ever “ultimate decree,” but Gaius Gracchus himself chose to commit suicide before he could be apprehended.

The glossary attached to The Grass Crown contains a much fuller article on the Gracchi.

guild An organized body of professionals, tradesmen, or slaves. One of the purposes behind the organization of guilds lay in protective measures to ensure the members received every advantage in business or trade practices, another to ensure the members were cared for properly in their places of work, and one interesting one, to ensure that the members had sufficient means at their deaths for decent burial.

Head Count The capite censi or proletarii: the lowly of Rome. Called the Head Count because at a census all the censors did was to “count heads.” Too poor to belong to a Class, the urban Head Count usually belonged to an urban tribe, and therefore owned no worthwhile votes. This rendered them politically useless beyond ensuring that they were fed and entertained enough not to riot. Rural Head Count, though usually owning a valuable tribal vote, rarely could afford to come to Rome at election time. Head Count were neither politically aware nor interested in the way Rome was governed, nor were they particularly oppressed in an Industrial Revolution context. I have sedulously avoided the terms “the masses” or “the proletariat” because of post-Marxist preconceptions not applicable to the ancient lowly. In fact, they seem to have been busy, happy, rather impudent and not at all servile people who had an excellent idea of their own worth and scant respect for the Roman great. However, they had their public heroes; chief among them seems to have been Gaius Marius—until the advent of Caesar, whom they adored. This in turn might suggest that they were not proof against military might and the concept of Rome as The Greatest.

Hellenic, Hellenized Terms relating to the spread of Greek culture and customs after the time of Alexander the Great. It involved life—style, architecture, dress, industry, government, commercial practices and the Greek language.

hemiolia A very swift, light bireme of small size, much favored by pirates in the days before they organized themselves into fleets and embarked upon mass raiding of shipping and maritime communities. The hemiolia was not decked, and carried a mast and sail aft, thus reducing the number of oars in the upper bank to the forward section of the ship.

herm A stone pedestal designed to accommodate a bust or small sculpture. It was chiefly distinguished by possessing male genitals on its front side, usually erect.

horse, Nesaean The largest kind of horse known to the ancients. How large it was is debatable, but it seems to have been at least as large as the mediaeval beast which carried an armored knight, as the Kings of Armenia and the Parthians both relied on Nesaeans to carry their cataphracts (cavalry clad in chain mail from head to foot, as were the horses). Its natural home was to the south and west of the Caspian Sea, in Media, but by the time of the late Republic there were some Nesaean horses in most parts of the ancient world.

Horse, October On the Ides of October (this was about the time the old campaigning season finished), the best war—horses of that year were picked out and harnessed in pairs to chariots. They then raced on the sward of the Campus Martius, rather than in one of the Circuses. The right—hand horse of the winning team was sacrificed to Mars on a specially erected altar adjacent to the course of the race. The animal was killed with a spear, after which its head was severed and piled over with little cakes, while its tail and genitalia were rushed to the Regia in the Forum Romanum, and the blood dripped onto the altar inside the Regia. Once the ceremonies over the horse’s cake—heaped head were concluded, it was thrown at two competing crowds of people, one comprising residents of the Subura, the other residents of the Via Sacra. The purpose was to have the two crowds fight for possession of the head. If the Via Sacra won, the head was nailed to the outside wall of the Regia; if the Subura won, the head was nailed to the outside wall of the Tunis Mamilia (the most conspicuous building in the Subura). What was the reason behind all this is not known; the Romans of the late Republic may well not have known themselves, save that it was in some way connected with the close of the campaigning season. We are not told whether the war—horses were Public Horses or not, but we might be pardoned for presuming they were Public Horses.

Horse, Public A horse which belonged to the State—to the Senate and People of Rome. Going all the way back to the Kings of Rome, it had been governmental policy to provide the eighteen hundred knights of the eighteen most senior Centuries with a horse to ride into battle—bearing in mind the fact that the Centuriate Assembly had originally been a military gathering, and the senior Centuries cavalrymen. The right of these senior knights to a Public Horse was highly regarded and defended.

hubris The Greek word for overweening pride in self.

hypocausis In English, hypocaust. A form of central heating having a floor raised on piles and heated from a furnace (the early ones were wood—fired) below. The hypocaust began to heat domestic dwellings about the time of Gaius Marius, and was also used to heat the water in baths, both public and domestic.

ichor The fluid which coursed through the veins of the gods; a kind of divine blood.

Ides The third of the three named days of the month which represented the fixed points of the month. Dates were reckoned backward from each of these points—Kalends, Nones, Ides. The Ides occurred on the fifteenth day of the long months (March, May, July and October), and on the thirteenth day of the other months. The Ides were sacred to Jupiter Optimus Maximus, and were marked by the sacrifice of a sheep on the Arx of the Capitol by the flamen Dialis.

Ilium The Latin name for Homer’s city of Troy.

Illyricum The wild and mountainous lands bordering the Adriatic Sea on its eastern side. The native peoples belonged to an Indo—European race called Illyrians, were tribalized, and detested first Greek and then Roman coastal incursions. Republican Rome bothered little about Illyricum unless boilingtribes began to threaten eastern Italian Gaul, when the Senate would send an army to chasten them.

imago, imagines An imago was a beautifully tinted mask made of refined beeswax, outfitted with a wig, and startlingly lifelike (anyone who has visited a waxworks museum will understand how lifelike wax images can be made, and there is no reason to think a Roman imago was very much inferior to a Victorian wax face). When a Roman nobleman reached a certain level of public distinction, he acquired the ius imaginis, which was the right to have a wax image made of himself. Some modern authorities say the ius imaginis was bestowed upon a man once he attained curule office, which would mean aedile. Others plump for praetor, still others for consul. I plump for consul, also the Grass or Civic Crown, a major flaminate, and Pontifex Maximus. All the imagines belonging to a family were kept in painstakingly wrought miniature temples in the atrium of the house, and were regularly sacrificed to. When a prominent man or woman of a family owning the ius imaginis died, the wax masks were brought out and worn by actors selected because they bore a physical resemblance in height and build to the men the masks represented. Women of course were not entitled to the ius imaginis—even Cornelia the Mother of the Gracchi.

imperator Literally, the commander-in-chief or general of a Roman army. However, the term (first attested to in the career of Lucius Aemilius Paullus) gradually came to be given only to a general who won a great victory; his troops had to have hailed him imperator on the field before he qualified for a triumph. Imperator is the root of the word “emperor.”

imperium Imperium was the degree of authority vested in a curule magistrate or promagistrate. It meant that a man owned the authority of his office, and could not be gainsaid provided he was acting within the limits of his particular level of imperium and within the laws governing his conduct. Imperium was conferred by a lex curiata, and lasted for one year only. Extensions for prorogued governors had to be ratified by the Senate and/or People. Lictors shouldering fasces indicated a man’s imperium; the more lictors, the higher the imperium.

in absentia In the context used in these books, a candidacy for office approved of by Senate (and People, if necessary) and an election conducted in the absence of the candidate himself. He may have been waiting on the Campus Martius because imperium prevented his crossing the pomerium, as with Pompey and Crassus in 70 B.C., or he may have been on military service in a province, as with Gaius Memmius when elected quaestor.

in loco parentis Still used today, though in a somewhat watered-down sense. To a Republican Roman, in loco parentis (literally, in the place of a parent) meant a person assumed the full entitlements of a parent as well as the inherent responsibilities.

insula An island. Because it was surrounded on all sides by streets, lanes or alleyways, an apartment building was known as an insula. Roman insulae were very tall (up to one hundred feet—thirty meters—in height) and most were large enough to incorporate an internal light well; many were so large they contained multiple light wells. The insulae to be seen today at Ostia are not a real indication of the height insulae attained within Rome; we know that Augustus tried fruitlessly to limit the height of Roman city insulae to one hundred feet.

in suo anno Literally, in his year. The phrase was used of men who attained curule office at the exact age the law and custom prescribed for a man holding that office. To be praetor and consul in suo anno was a great distinction, for it meant that a man gained election at his first time of trying—many consuls and not a few praetors had to stand several times before they were successful, while others were prevented by circumstances from seeking office at this youngest possible age. Those who bent the law to attain office at an age younger than that prescribed were also not accorded the distinction of being in suo anno.

interrex “Between the kings.” The patrician senator, leader of his decury, appointed to govern for five days when Rome had no consuls. The term is more fully explained in the text.

Iol Modern Cherchel, in Algeria.

Italia The name given to all of peninsular Italy. Until Sulla regulated the border with Italian Gaul east of the Apennines by fixing it at the Rubico River, the Adriatic side probably ended at the Metaurus River.

Italian Allies Certain states and/or tribes within peninsular Italy were not gifted with the Roman citizenship until after they rose up against Rome in 91 B.C. (a war detailed in The Grass Crown). They were held to be socii, that is, allies of Rome. It was not until after Sulla became dictator at the end of 82 B.C. that the men of the Italian Allies were properly regulated as Roman citizens.

Italian Gaul See the entry under Gaul.

iudex The Latin term for a judge.

iugerum, iugera The Roman unit of land measurement. In modern terms the iugerum consisted of 0.623 (five eighths) of an acre, or 0.252 (one quarter) of a hectare. The modern reader used to acres will get close enough by dividing the number of iugera in two; if more accustomed to hectares, divide the number of iugera by four.

Iulus Strictly speaking, the Latin alphabet owned no J. The equivalent was consonantal /, pronounced more like the English Y. If rendered in English, Iulus would be Julus. Iulus was the son of Aeneas (q.v.) and was believed by the members of the gens Julia to be their direct ancestor. The identity of his mother is of some import. Virgil says Iulus was actually Ascanius, the son of Aeneas by his Trojan wife, Creusa, and had accompanied Aeneas on all his travels. On the other hand, Livy says Iulus was the son of Aeneas by his Latin wife, Lavinia. What the Julian family of Caesar’s day believed is not known. I shall go with Livy; Virgil was too prone to tamper with history in order to please his patron, Augustus.

ius In the sense used in this book, an incontrovertible right or entitlement at law and under the mos maiorum. Hence the ius auxilii ferendi (q.v.), the ius imaginis (see imago), and so forth.

ius auxilii ferendi The original purpose of the tribunate of the plebs was to protect members of the Plebs from discriminatory actions by the Patriciate, this latter group of aristocrats then forming both the Senate and the magistracy. The ius auxilii ferendi was the right of any plebeian to claim to the tribunes of the plebs that he must be rescued from the clutches of a magistrate.

Jupiter Stator That aspect of Jupiter devoted to halting soldiers who were fleeing the field of battle. It was a military cult of generals. The chief temple to Jupiter Stator was on the corner of the Velia where the Via Sacra turned at right angles to run down the slope toward the Palus Ceroliae; it was large enough to be used for meetings by the Senate.

Kalends The first of the three named days of each month which represented the fixed points of the month. Dates were reckoned backward from each of these points—Kalends, Nones, Ides. The Kalends always occurred on the first day of the month. They were sacred to Juno, and originally had been timed to coincide with the appearance of the New Moon.