ten

The Enemies Within

One of the stories later told about Richard the Lionheart was that, as he lay dying, he humorously shed his principal vices, leaving his avarice to the Cistercians, his love of luxury to the mendicant friars, and his pride to the Templar Knights.223 This same sin of pride was also ascribed to the Templars by Richard’s contemporary, Pope Innocent III, one of the most outstanding men to wear the papal tiara in the two-thousand-year history of the Catholic Church.

Elected in 1198 at the young age of thirty-seven, Innocent was the son of the Count of Segni and so a member of the patrician Roman family of Scotti who provided a number of popes in the eleventh and twelfth centuries: Innocent’s uncle, Pope Clement III, had made him a cardinal in 1190, and both a nephew and a great-nephew were to become popes. However, if an element of nepotism had entered into his advancement, it did not mean that Innocent was not the best man for the job. He was exceptionally intelligent, of great integrity, witty, magnanimous, ‘keenly alert to the absurd in the events and people around him’,224 yet utterly convinced that, as supreme pontiff and the ‘Vicar of Christ’ – a term he was the first to use – he had authority over the whole world, ‘lower than God but higher than man: one who judges all, and is judged by no one’.

By training, Innocent was a canon lawyer, the first of a number of lawyer-popes, but his approach was never narrow or pedantic. With extraordinary energy, he promoted the pastoral reform of the Catholic Church and the clarification of its teaching that was codified in the decrees of the Fourth Lateran Council that met in 1215. He insisted upon orthodoxy: it was a time when, beneath the superficial uniformity of the Catholic faith, there were many undercurrents of religious enthusiasm and variant belief. The affluence and worldliness of many of the clergy provoked challenges to the Church. Innocent was sufficiently open-minded to recognise the value of an idealistic innovator like Francis of Assisi but he condemned and set out to extirpate the heretical teaching of the Cathars in Languedoc.

Like all popes since Urban II, Innocent III was an enthusiastic supporter of the war against Islam. In 1198, soon after his accession, he called for a new crusade and in 1199 wrote to the bishops and barons of Outremer to complain that treaties with the Saracens undermined his attempts to persuade Christians in Europe to take the Cross. To finance the crusade he imposed a two-and-a-half-per-cent tax on Church income. He granted a plenary indulgence, the forgiveness of all confessed sins, not just for those who went to Palestine but also those who sent proxies in their place. The waging of a Holy War in the Holy Land now became accepted ‘as an ideal in the daily lives of Western Europeans’;225 but ‘the presence of the crusade in late medieval Europe was perhaps more than anything else that of the armies of collectors, bankers, bureaucrats who busied themselves assembling and distributing money without which nothing could be done’.226

Like Richard the Lionheart, Innocent III had an ambivalent attitude towards the Order of the Temple. He was aware of its failings. The popes, as the overall sovereigns of the military orders, were constantly assailed by complaints against the knights, either from secular leaders such as King Amalric of Jerusalem in the case of the killing of the Assassin envoys by the Templars; or more often from the clergy who felt that their rights had been transgressed. Since most of the chroniclers of the period were clerics, such as William of Tyre, they probably give an exaggerated impression of the opprobrium felt for the Temple by the public at large.

Some of the charges are quite trivial – for example, that the ringing of bells in the Hospitaller compound in Jerusalem disturbed the Patriarch of Jerusalem and confused the canons of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Others stem directly from the privileges that the popes had given to the military orders, in particular exemption from the payment of tithes. At the Third Lateran Council in 1179, a number of decrees were passed curtailing the privileges of the military orders which had later to be annulled by the Pope. In 1196 Pope Celestine III rebuked the Templars for breaking an agreement they had made with the same canons of the Holy Sepulchre over the division of tithes; and in 1207 Pope Innocent III chided them for disobeying his legates, exploiting the privilege of saying Mass in churches placed under interdict, and admitting anyone ‘willing to pay two or three pence to join a Templar confraternity … even if he is excommunicate’ with the result that adulterers and usurers could be assured of a Christian burial. They were, he said, ‘exhaling their greed for money’.227

Few questioned the very existence of the military orders. The Cistercian Abbot of l’Etoile near Poitiers, an Englishman called Isaac, in the mid-twelfth century preached against the ‘new monstrosity’ of the nova militia, a term which echoed Bernard of Clairvaux’s tract in favour of the Templars, De laude novae militiae: he denounced those who used force to convert Muslims and regarded as martyrs those who died while despoiling non-Christians. Later in the twelfth century, two other Englishmen, the chroniclers Walter Map and Ralph Niger, also questioned the use of force to spread the Christian religion. Walter Map, an enemy of the Cistercians, criticised the Templars for their avarice and extravagance, contrasting those vices with the poverty and charity of their founder, Hugh of Payns.

Resentment against the Templars was exacerbated by their culture of secrecy. In the Holy Land there were good military reasons why their deliberations should not be disclosed, but in Europe it was rather that they did not want their failings to become known. It was in chapter that the transgressions of the brothers were confessed and penances imposed; like most institutions, the Templars preferred to hide their shortcomings, and by the middle of the thirteenth century ‘all three [military] orders contained regulations forbidding the brothers to make public the chapter proceedings of the order, or to allow outsiders to see copies of the rule’.228 Great secrecy also surrounded the ceremony of reception into the Order.

A source of envy was the apparent wealth of the Order of the Temple which, given the bad news that came from the Holy Land, made many wonder if they were giving value for money. Unlike the monastic orders, they made only a minor contribution to the medieval welfare state: one of the first critics of the Order, John of Würzburg, conceded that they did give alms to the poor but not as generously as the Knights of the Hospital. As with the Benedictines and the Cistercians, past endowments and successful estate management had made both the Temple and Hospital among the richest corporate bodies in the kingdoms of western Europe. Among the spiritual descendants of Benedict of Nursia and Bernard of Clairvaux, this wealth had led to considerable compromises with their original ideals, with the charism of apostolic poverty passing to the orders of friars such as the Franciscans until they in turn were corrupted by their success.

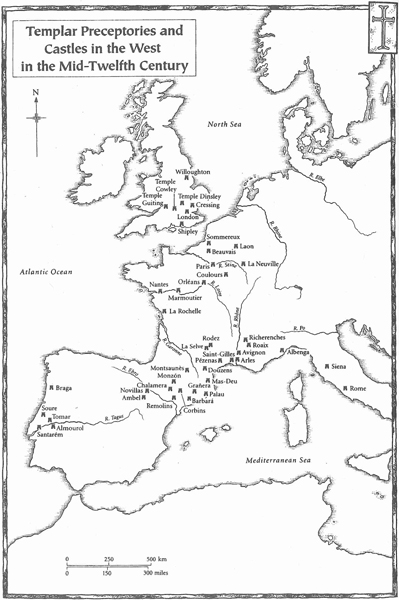

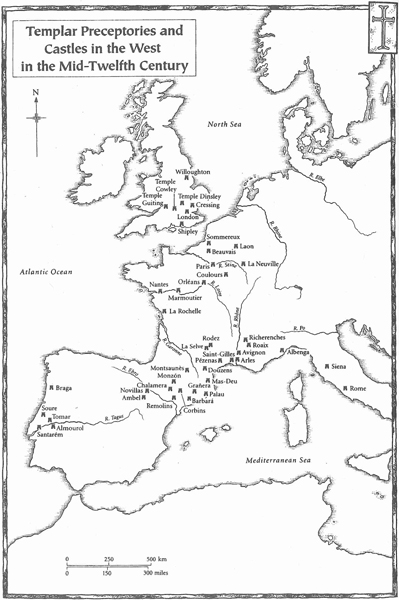

Despite this trend among the religious, the Templars lived in a state of rough frugality. Outside the capital cities, or the territories where they were at war, they did not spend large sums on great castles or magnificent churches: the extant commanderies such as Richerenches appear quite modest, particularly when compared to the splendour of the monastic foundations. The buildings of their commanderies and preceptories were wholly practical: barns to store their corn, stables for the horses, dormitories to house the half-a-dozen or so brothers who staffed them, and modest fortifications to keep out thieves. Their churches were also modest and were built as symbols of their mission: the salient feature of both Templar and Hospitaller churches was the rotunda copied from the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. Both orders ‘vied to associate themselves in the public eye with the defence of the site of the Resurrection’.229

The public perception of the military orders was that they were wealthy, but ‘the orders themselves were at pains to point out to new recruits that life in the orders was not as comfortable as their image might have led them to believe’. Direct accusations of luxure ‘were reserved for Cluniacs and bishops’.230 A more telling charge against the Templars in Europe was that, while all claimed the exemptions that had been given to the Order, only a small proportion actually took up arms against the infidel. The great majority were administrators of the more than 9,000 manors that had been given to the Order by pious benefactors over the years or the labourers who worked on them, the Templars’ ‘men’. The exemptions from feudal justice and obligations enjoyed by even these subordinate members of the Order were inevitably resented by the feudal lords. By and large, since it was the royal courts who upheld their privileged status, relations with royal officials were cordial; but there were instances, for example in the Bulmer Hundred in Yorkshire, when the Templars abused their privileges by enrolling felons and robbers into the Order and preventing royal justices from making arrests.

Like the Cistercians, the Templars managed their own estates. In England, they had holdings as far west as Penzance or in such remote places as the island of Lundy. In Lincolnshire and Yorkshire they contributed significantly to the development of agriculture, and drew recruits from the families who had bequeathed the land. Criticism of the Order was often counterbalanced by praise, particularly from barons returning from the crusades. A great magnate in the north of England, Roger of Mowbray, Earl of Northumberland, after being captured by Saladin at Hattin, had his ransom paid by the Temple and, on his return, expressed his gratitude in a number of benefactions.

The Templars’ reputation for probity meant that they were trusted both to hold the money of others and to transfer it to different locations. It was through the Temple in London that King Henry II built up a crusading fund in Jerusalem that proved so useful at the time of Hattin. The Templars also lent money to individuals and institutions, including the Jews, but their principal clients were kings and their loans frequently staved off the collapse of royal finances. Fortuitously, the Templars thus became the bankers of Christendom and held in their vaults not just the wealth of the Order but the treasure of kings. The Paris Temple became ‘one of the key financial centres of north-west Europe’.231 Its great keep, or donjon, a turreted tower that was to serve as a prison for King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette at the time of the Revolution of 1789, would have had its equivalent in the London Temple where today only the church is extant. In Paris it is estimated that around four thousand men marked with the cross of the Order resided in the Temple, though few of these would be in the white habit of a fully fledged knight.

In the Kingdom of Aragon, the kings were constantly borrowing money from the Temple and in France the order often had difficulty in meeting the royal demands.232 Church institutions were readier to lend money to the Crown if the Temple secured the loan. In Aragon, loans were made on the security of an income from land or a benefice, and ‘it was often agreed that the Order could deduct part of the sum collected to cover its expenses, as was permitted in canon law’. On some loans they charged interest of ten per cent which was ‘two per cent less than the maximum allowed to Christian moneylenders in Aragon and half of the Jewish rate’ and while ‘in a few instances the Templars definitely obtained a direct monetary gain from moneylending, on some other occasions they appear not to have done so’.233

Among the financial services provided by the Templars were the provision of annuities and pensions. Frequently a donation of land or money would stipulate that it should provide for a man and his wife until they died: ‘there were few ways of providing for one’s old age or the welfare of one’s dependants except by making a gift to an ecclesiastical institution’.234 Payment was also made for a package of spiritual and temporal benefits: for the salvation of the donor’s soul and protection by the Temple in a society where violence was endemic, there was much to be said for having a Templar cross on one’s property whether or not one was also under the nominal protection of a liege lord.

This function of the Templars as a form of police force had, of course, been envisaged by their founder, Hugh of Payns: now it was extended from escorting pilgrims in Palestine to safeguarding the transfer of cash. In July 1220, Pope Honorius III told his legate, Pelagius, that he could find no one whom he trusted more to transport a large sum of money.235 Templars also worked as civil servants: brothers of the Temple and Hospital are frequently found serving both popes and kings. As monks, they had the habit of obedience and, as celibates, no dynastic ambitions. Their status as knights gave them authority and qualified them to take on military duties: for example, Pope Urban IV appointed three Templar brothers to take charge of castles in the Papal States, and at Acre the Temple and Hospital were the only bodies trusted by both Richard the Lionheart and Philip Augustus. With their financial acumen, Templars were often made royal almoners by the European kings.

Despite the unitary structure of the military orders, the knights’ vow of obedience to their Grand Master, and their fealty to the Pope, it seems to have been accepted that brothers in the same Order should work for monarchs whose interests diverged from one another, or from those of the Pope. In almost every European kingdom, Templars and Hospitallers were a source of dependable public servants, and as such were in a position to exert influence in favour of their Orders. King John of England, who succeeded his brother Richard, was excommunicated by the Pope and yet was advised by the Templar Master in England, Aimery of Saint Maur: he was almost the only man John trusted. In the same way, the Emperor Frederick II, in his constant conflicts with the Papacy, was counselled and supported by the Hermann of Salza, the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights.

The presence of Templars in the councils of popes and kings puts Innocent III’s criticisms of the Order in perspective. Despite their pride, and the occasional abuse of their privileges, the military orders had become indispensable to the papal governance of Christendom and so received full papal support. Thus, when the Patriarch Fulcher of Jerusalem went to Rome to persuade the Pope to revoke some of the privileges of the Hospital he got nowhere. The chronicler, William of Tyre, put this down to bribery but it seems more likely that the Curia’s attitude reflected the growing disenchantment in Europe with the Latins in Outremer and that it saw in the military orders the most effective means of achieving the Church’s objectives. In the same way, the decrees passed by the third Lateran Council curtailing the privileges of the military orders were reversed by later popes.236

Innocent III was even more emphatic in his defence of the Templars’ privileges and exemptions, insisting upon the Order’s right to build churches, to have their own cemeteries, to collect their own tithes; and he warned the clergy not to interfere with the Templars’ rights by taking tithes from their estates or putting their churches under interdict. He denounced bishops who had imprisoned Templars and insisted that they punish anyone who robbed Templar houses. He suspended the Bishop of Sidon for excommunicating the Grand Master of the Temple in a dispute over the revenues of the diocese of Tiberias; renewed all the privileges given to the Temple by Pope Innocent II’s bull of 1139, Omne datum optimum; and, giving us an insight into the way popular resentment against the Templars found expression, condemned anyone who attacked a Templar knight and dragged him from his horse.

Given that the popes had supreme authority over the military orders, it shows some restraint that there is only one instance where they involved them in their own wars: in 1267, Pope Clement IV asked for Hospitaller help against the Germans in Sicily.237 Clearly, where they were in the service of popes or kings, individual knights belonging to the military orders were expected to take up arms to protect their masters’ interest, and there were instances where the kings of Aragon summoned the Templars’ men, and even the knights themselves, to fight against the Castilians and the French. However, this was the exception, not the rule. ‘The Crown was clearly wary of using the Templars themselves against its Christian enemies’ and the Templars were reluctant so to be used: the kings had to threaten strong measures to ensure that their summons would be obeyed.238

Two other areas where the Templars came into armed conflict with their fellow Christians were Cyprus and Armenian Cilicia. The uprising against the Templars in Nicosia in 1192 had been forcefully put down and, even after the island had been resold to Guy of Lusignan, the Templars held on to the stronghold of Gastria, north of Famagusta, and had fortified estates at Yermasoyia and Khirokitia, and a fortified house in Limassol. In Cilicia, the order came to blows with Leo, the Prince of Lesser Armenia, over the fortress of Gaston overlooking Antioch in the Amanaus Mountains.

* * *

In the two most significant conflicts between Christians in this period, the Templars were only marginally involved. The first was the Fourth Crusade that set out in response to Pope Innocent III’s first appeal on his accession for aid to the Holy Land and, like the First Crusade, was led by a group of secondary rulers with a crusading pedigree such as Count Louis of Blois, Count Baldwin of Flanders and Count Theobald of Champagne.

Since the death of the Emperor Barbarossa in Anatolia, the land route to the East was considered impassable and so envoys of these magnates went to Venice to arrange for passage by sea. The Doge of Venice, Enrico Dandolo, though an old man, was far from senile: he agreed that for the sum of 85,000 silver marks the republic would provide a fleet of fifty galleys and transport for 4,500 knights, 9,000 squires and 20,000 foot-soldiers with sustenance for a year. The date of departure was set for twelve months’ time.

The ostensible aim of this expedition was to liberate Jerusalem because now, as at the time of the First Crusade, Western Christians were only prepared to risk their lives for the Holy City: but in a secret clause to the treaty, it was agreed that the crusade would attack Egypt. Since the Third Crusade a consensus had grown up among the leaders of the Latins, both in Europe and in Outremer, that Jerusalem could never be secure while menaced from Cairo. However, the Venetians, who had profitable trading links with the Ayyubids (sultans descended from Saladin’s father, Ayyub) in Egypt, almost certainly had no intention of aiding an assault on the Nile.

Count Theobald of Champagne died early in 1201 and the high command of this new expedition chose as their new leader Marquis Boniface of Montferrat. However, on the date set for their departure only around 10,000 men had assembled in Venice and there was a deficit of 35,000 marks in the sum that had been promised to the Venetians. The Venetians refused to lower their price but agreed to accept in lieu the help of the crusading army in taking the city of Zara on the Dalmatian coast en route to the East. This was held by the Christian King of Hungary and many of the crusaders objected, among them the Cistercian Abbot of Les-Faux-de-Cernay and a French baron, Simon of Montfort. They were overruled; Zara was taken. Innocent III was so outraged at this attack on a Christian king that he excommunicated the whole army; but, faced with the collapse of the crusade, the sentence was rescinded.

While wintering in Zara, intending to continue east in the spring, the crusading army was approached by a Greek prince, Alexius IV Angelus, who had a claim to the Byzantine throne. He proposed that, if the Western army would return his father to the throne, he could guarantee a reunion of the Orthodox with the Catholic Church, large subventions and ten thousand Byzantine soldiers to join the crusade. The idea appealed to the Doge, Enrico Dandolo, and to Boniface of Montferrat but was opposed by the same parties who had objected to the attack on Zara: Simon of Montfort and the Abbot of Les-Faux-de-Cernay. Again, they were overruled and as a result abandoned the crusade.

The restoration of a legitimate ruler was a just cause in the canon of feudal law, and the bishops accompanying the crusade were persuaded to support it; but when the fleet arrived off Chalcedon opposite Constantinople in June 1203, there were other less creditable emotions in the minds of the Latin warriors. The French remembered the ordeal of King Louis VII and the knights on the Second Crusade as they had marched across Anatolia in 1148, which the King had blamed on the perfidy of the Greeks; and Enrico Dandolo had his own reasons for loathing the Greeks: he had lost his sight during the pogroms against the Latins in Constantinople in 1182.

The memory of this atrocity was still vivid in the minds of the Latins: we can see its effect on the history of William, Archbishop of Tyre. At first his only criticism of the Byzantines is that they are too weak to defend the Holy Places, but he considers them worthwhile as allies against the Saracens. After the pogroms of 1182, his illusions are shattered; he decides that he has been wrong about ‘the deceitful and treacherous Greeks’ whose ‘pseudo-monks and sacrilegious priests’ are not just schismatics but heretics239 – the most damning epithet that a medieval churchman could devise.

Acting on this latent hatred was ‘the medieval soldier’s notorious greed for booty’,240 something which to those living in an age of well-paid and even cosseted armies seems more reprehensible than it did at the time. It was not just that the barbarian passion for plunder was still strong in the Frankish psyche, but also that all military campaigns had to some extent to pay for themselves. What Innocent III had failed to appreciate was that, despite his tax on the clergy, the costs of crusading were beyond the resources of all but the richest kings. By giving the go-ahead to the minor magnates like the counts of Blois, Flanders and Champagne, he may have hoped to keep a greater measure of papal control over the expedition than if he had waited on the kings of England and France; but, as the taking of Zara had demonstrated, his control was tenuous; and the crusade was inadequately funded.

It is also clear that in this, as in all other crusades, the penitential motivation was combined with the hope in the minds of many of the participants that they would both save their souls and make their fortunes: it was wholly accepted among all parties to these incessant conflicts that risk should have its reward. Despite this, however, there can be no doubt that what now followed was ‘a scandalous undertaking’,241 even if it remains unclear who was to blame. In June 1203, soon after their arrival, the crusaders attacked the outskirts of Constantinople, captured the suburb of Galeta and broke the chain that protected the entrance to the city’s harbour, the Golden Horn. On 17 July they mounted an assault on Constantinople itself but were beaten back by the Emperor’s Varangian Guard. This was enough, however, to frighten the Emperor Alexius III into flight and put the crusaders’ candidate Isaac Angelus on the throne.

Despised by his Greek subjects as a stooge of the Latins, the new Emperor was unable to raise the money that had been promised to the crusaders and in January 1204 he was deposed and murdered by the angry populace together with his son. The Emperor who replaced him, Alexius V Ducas, was more to the Greeks’ liking but he antagonised the crusaders. On 12 April 1204 they attacked the city and within a day it was taken. The ancient and as yet unconquered capital of the eastern Roman Empire was subjected to the slaughter of its inhabitants and the pillage of its treasures. Most prized were the repositories of relics that, as magnets to attract pilgrims to churches in Europe, were worth very much more than their weight in gold. One of the chroniclers of the sack of the city, Gunther of Pairis, described how a Latin abbot, finding the store of relics in the Church of Christ the Pantocrator after threatening to kill a Greek priest if he did not tell him where they were hidden, ‘filled the folds of his gown with the holy booty of the Church which, laughing happily, he then carried back to the ship’.242

Not only the treasures of Constantinople but those of the Byzantine Empire itself were shared out among the Latin conquerors. On 16 May Baldwin of Flanders was crowned emperor in the cathedral of Hagia Sofia and was given lands in Thrace, parts of Asia Minor and some of the Cycladic islands. Boniface of Montferrat founded a kingdom in Thessalonika while the Venetians took over the Byzantine possessions on the Adriatic coast, cities on the coast of the Peloponnese, Euboea, some the Ionian islands and Crete. Constantinople was also subdivided into quarters with the Venetians taking almost half the city. Not only had Enrico Dandolo taken his revenge; he had also established Venetian control over the trade routes from the Adriatic to the Black Sea.

None of those who had set out under Boniface of Montferrat went on to the Holy Land. All stayed to stake their claim to fiefs on the carcass of the Byzantine Empire. From now on, potential recruits among the landless knights of western Europe who might have sought their fortunes in Syria and Palestine were diverted by the easier opportunities offered by fiefdoms in Greece. It was therefore not just the Byzantine Greeks who suffered from the conquest of their empire but the beleaguered Christians in the Holy Land whom the crusaders had set out to assist. Even the Templars, though they had played a negligible role in the Fourth Crusade, took part in the conquest of central Greece between 1205 and 1210.243 Together with the Hospitallers and the Teutonic Knights, they acquired lands in the Peloponnese and, ‘although the military service they owed was nominal’,244 did contribute ‘to the defence of the Latin empire of Constantinople’.245

* * *

The second major conflict between Christians which followed soon after the conquest of Byzantium was the Albigensian Crusade, named after the city of Albi in south-west France. This was a centre for the Cathars, a heretical sect that had established itself in the rich territories stretching from the River Rhône to the Pyrenees, known because of its distinctive French dialect as the langue d’oc. The origins of Catharism are found in the ancient Zoroastrian religion of Persia. This held that there were two Gods, a benevolent deity whose realm was pure spirit and a malevolent one who had created the material world. Everything material was therefore intrinsically evil and salvation lay in emancipating oneself from the flesh. Buddhism, Stoicism and Neoplatonism showed a certain affinity with this condemnation of matter, while Christianity, despite its esteem for self-denial, held that God not only approved his material creation but, in Jesus, became part of that material creation as the Word made flesh.

Dualistic concepts affected the belief of Christians from the earliest days of the Church. Part of their appeal lay in the solution they posited to the eternal conundrum: why, if the Devil was God’s creation, did God continue to permit him to exist? Condemnation of the flesh, and all the bestial and selfish passions that it engendered, seemed to accord with the teaching of Christ. To the dualists, celibacy was not a matter of choice. All carnal intercourse was evil and to have children was to co-operate with the Demiurge or Devil in the perpetuation of matter. Marcion, for example, a Christian heretic in the second century, forbade marriage and made celibacy a condition of baptism.

In the third century, a Persian, Mani, taught that to avoid contact with the evil of the material world one should neither work, fight nor marry. After he was martyred for his beliefs by the Zoroastrian hierarchy in 276, Mani’s ideas spread from Persia to the Roman Empire and made converts such as the young Augustine of Hippo. In the fifth century, a vigorous community of Manicheans, the Paulicians, was established in Armenia. They became sufficiently powerful to provoke the Byzantine emperors to send military expeditions against them and, in the tenth century, to deport them en masse to Thrace in northern Greece. From here, their ideas spread into Bulgaria and were adopted by the followers of a Slav priest called Bogomil who founded a dualist church in the Balkans. Like the Paulicians, the Bogomils rejected the Old Testament, Baptism, the Eucharist, the Cross, the sacraments, and the whole structure of the visible church. They too thought that to have children was to collaborate with the Devil in the perpetuation of matter and some avoided it through anal intercourse: the word ‘bugger’ comes from Bulgar.

Despite persecution by the Orthodox emperors, the Bogomil Church survived until the conquest of the Balkans by the Ottoman Turks when many of the Bosnian Bogomils became Muslims. Some pockets of Paulicians were encountered by the forces of the First Crusade in the neighbourhood of Antioch and Tripoli; and it is possible that returning crusaders brought dualist ideas back to western Europe. They were found in the crusaders’ home territories such as Flanders, the Rhineland and Champagne and were vigorously and effectively suppressed.

In southern Europe dualist theories had to compete with other unorthodox ideas, in particular those of a merchant from Lyons called Peter Valdes who, though not a dualist, rejected the idea that sacramental grace was necessary for salvation. He condemned the gross wealth of the clergy and left his wife and possessions to live as a hermit. His view of poverty as a paramount virtue was not so different from that of Francis of Assisi, and it has been said that whether the holy men of the period ‘were revered as saints or excommunicated as heretics seemed to be largely a matter of accident’.246 Clearly, it was not always easy to distinguish between zeal for reform, anticlericalism and the promotion of ideas inimical to Christian teaching: but the success of Islam had shown what could result when heretical ideas went unchecked and were exploited by an emerging social class. The greatest support for those who attacked the wealth of the Church came from the rising class of merchants in the cities of Lombardy, Languedoc and Provence.

In Languedoc there were other factors that favoured the spread of the Cathar religion. As Bernard of Clairvaux had seen when he had preached against Henry of Lausanne, the Church was in a deplorable condition, with negligent, greedy, ignorant priests and bishops more intent on fleecing than guarding their flocks. At the same time, contact with Islamic ideas that came with trade with Moorish Spain, and the prominent role played by the Jews in the economy of the region, created a climate of tolerance towards other beliefs. There was less centralised control because many of the minor principalities were held as freeholds, not fiefs. Even those barons that held fiefs had no single feudal lord: some held them from the Count of Toulouse, others from the kings of Aragon and even, notionally, the German Emperor. Anticlericalism was rife. Much of the wealth enjoyed by the corrupt clergy had been given by the ancestors of the landed nobility who, seeing them now in apparently unworthy hands, did what they could to claw them back. This brought them into constant conflict with both the local bishops and the Pope. It was therefore hardly surprising that a religion that thought the clergy superfluous should have considerable appeal.

What at first sight seems incongruous is that ‘a turbulent, restless, egotistical society’,247 perhaps the most educated, cultured and hedonistic in Europe – a haven for jongleurs and troubadours, the poets of courtly love – should have proved so receptive to the bleak dualism of the Cathars. But it should be remembered that only a few of their number, known as the parfaits, led lives of superhuman self-denial: for the mass of credentes, the mere believers, the Cathar doctrine was that only one sacrament was necessary for salvation, and that the last one, the consolamentum which washed away all sins, made it unnecessary to strive to be virtuous until faced with death. Catharism was also a religion that appealed to women: female parfaits were accorded the same reverence as those who were men. As a French priest was to put it, ‘Les hommes font les hérésies, les femmes leur donnent cours et les rendent immortelles’: men may invent heresies but it is women who spread them and make them immortal.248

* * *

In 1167, the Greek ‘pope’ of the Cathars from Constantinople, Niquinta, presided over a council of the faithful outside a town near Castelnaudary in Languedoc, Saint-Félix-de-Caraman. Already, by this time, there was a Cathar bishop of Albi and now further bishops were appointed to Toulouse, Carcassonne and Agen. The Catholic bishops in Languedoc, horrified by the spread of this heretical sect, tried to counter it with public disputations but to no avail. Reports of its growth and entrenchment reached Rome. When a zealous Castilian, Dominic Guzman, the prior of the canons of the cathedral of Osma, called on Pope Innocent III in 1205 to ask for his permission to preach the Gospel to the pagans on the Vistula, Innocent accepted his mission but redirected it to the south of France. Two years earlier he had appealed to the Cistercians to reconvert the Cathars and, despite their best efforts, they had failed.

Dominic, playing the parfaits at their own game, adopted a lifestyle of abject poverty and rigorous mortification. He joined the Cistercians in preaching the orthodox Catholic faith and debating with the Cathar divines. Again, persuasion failed. Innocent, who recognised perfectly well the grave shortcomings of the Catholic clergy in Languedoc, deposed seven bishops in the region and replaced them with incorruptible Cistercians and repeatedly appealed to the counts of Toulouse to take action; but the counts were unwilling and probably unable to do so because the roots of Catharism had grown too deep. Too many Catholics had Cathar brothers, sisters or cousins who were seen to lead exemplary lives.

The Catholic hierarchy regarded the triumph of this heretical religion with dismay. It was not simply that Catharism removed their raison d’être, though that may well have been a factor among the prelates of Languedoc. It was rather that souls placed by God in their care were being lured to eternal damnation. The Cathars had an especial hatred both for the Cross which they thought blasphemous for its depiction of the suffering divinity, and for the Mass which they thought sacrilegious because it claimed that at the consecration the bread became the flesh of Christ. Rather than live peaceably side by side with Christians, they made no bones about their ambition to destroy the Church: in 1207 the Cathars of Carcassonne ejected the Catholic bishop from the city.

In medieval Europe, however Church and society were coterminous; the year was punctuated with the fasts and feasts of the Christian calendar and life mediated through the sacraments. Vows, which the Cathars condemned, were the basis upon which the whole structure of feudal society was based. Apostasy would lead to anarchy and undermine the most fundamental human institutions. That this was not an extravagant fantasy was confirmed by the Cathar teaching that marriage, in the words of an apostate heretic, Rainier Sacchoni, was ‘a mortal sin … as severely punished by God as adultery or incest’.249

After the failure of repeated campaigns of persuasion, Pope Innocent called upon the principal ruler of the region, Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, to extirpate the heresy by force. In 1205 Raymond promised to do so but did nothing. In 1207, after a meeting with Raymond at Saint-Gilles in Provence, the Papal Legate, Peter of Castelnau, was killed by a man from Raymond’s entourage. This outrage prompted Innocent III to proclaim a crusade. There followed twenty years of warfare with indiscriminate massacres on both sides that only ended with the annexation of Languedoc by the King of France. The Cathars were hunted down and burned, some happily consigning their corrupt bodies to the flames. The heresy was eventually destroyed but with it went what some historians see as a uniquely refined and cultivated civilisation and others ‘a society in an advanced stage of disintegration which still clung to the husk of a civilisation that had all but disappeared’.250

* * *

The first leader of the Albigensian Crusade was Simon of Montfort, the same knight from northern France who had abandoned Boniface of Montferrat and the Venetians at Zara. At one point the whole of Languedoc was within his grasp and, like the Franks in Palestine or the Normans in Antioch, he might have founded a dynasty while in the service of the Church; but with the changing fortunes of the war this prize eluded him and he was eventually killed while besieging Toulouse.

To the native nobility, whether Catholic or Cathar, the crusade was an invasion of their homeland by an enemy from the north; and despite a constant flux of loyalties they fought to defend it. Feudal loyalties and political interests became inextricably entangled with religious zeal leading to paradoxical alliances: King Peter II of Aragon, who had won a major victory against the Muslims in Spain at Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212, was killed in the following year fighting Simon of Montfort outside the walls of Muret.

What was the role of the military orders in this internecine warfare and fratricidal strife? Both the Temple and the Hospital had considerable holdings in the region. Raymond of Saint-Gilles, Count of Toulouse, had been among the leaders of the First Crusade, and both his descendants and those of his vassals had settled substantial benefices on the military orders, particularly the Hospital. However, the preceptory of Mas-Deu in Roussillon was one of the most important strongholds of the Temple. Both orders were also heavily engaged in the Kingdom of Aragon and committed to the war against Islam in Spain.

As a result, a war between Simon of Montfort on behalf of the Pope, and Count Raymond VI and King Peter II of Aragon together with most of the nobility of Languedoc, led to divided loyalties among the military orders. By and large, both attempted to remain neutral and were recognised as such by the Treaty of Paris that eventually brought the conflict to an end. Where the orders were drawn into the conflict, it seems that the Hospital sided with Raymond VI and Pedro II, and the Temple with the crusaders. Templars had fought with Pedro II at Las Navas de Tolosa, but ‘all respected unreservedly their duty towards the pope and the Church … The fidelity of the Knights Templar to Simon of Montfort and the crusades never diminished’:251 in 1215 we find Simon staying in the Templar house outside Montpellier.

However, it seems to have been accepted that the Templars’ primary commitment was to the war against Islam in the East; certainly Pope Innocent III made no attempt to enlist them against the Cathars and the foundation of an order modelled on the Temple by Conrad of Urach in 1221, the Militia of the Faith of Jesus Christ, would seem to confirm this. It was possibly as vassals of the King of France that they are found with Prince Louis at the taking of Marmande in the spring of 1219, witnesses to, if not participants in, the slaughter of the inhabitants of the city. In 1226, King Louis VIII of France, when besieging Avignon, vested full powers in his absence to a Templar knight, Brother Everard, dispatching him to Saint-Antonin to accept the city’s surrender.252

The charge of Templar support for the Cathars, which was to inspire a number of fabulous theories in modern times, is more credible if levelled at the Hospitallers but here again there is no evidence that they showed any sympathy for the heretical religion. From the time of its evolution into a military order, the Hospital had had close links with the counts of Toulouse both in Europe and in Outremer. There were numerous foundations in Languedoc, while in Syria the great fortress of Krak des Chevaliers had been given to the Hospital by Raymond II of Tripoli, a great-grandson of Raymond IV of Toulouse. During the Albigensian Crusade, therefore, their sympathy tended to be for the descendants of their benefactors to whom the knights themselves, unlike the knights of the Temple, were frequently related. Thus we find that some of the most courageous defenders of the Cathars who asked to receive the consolamentum from their parfaits also endowed the Hospital and asked to be admitted as confrères, suggesting that they either had little understanding of theology or that they were hedging their bets.

The Hospital benefited from its links with the enemies of the crusade. After the death of Simon of Montfort at the siege of Toulouse, and the retreat of the crusaders, the Catholic bishops and the Cistercians withdrew from the area and the Templars abandoned their preceptory at Champagne but the Hospitallers and the Benedictines remained: the Benedictines at Alet were later evicted from their abbey for complicity with the Cathars.253 Probably the most overt demonstration of their loyalties came with the death of King Pedro II of Aragon at the Battle of Muret: the Hospitallers asked for and were given permission to retrieve his dead body from the field. Similarly, they admitted Raymond VI as a confrère and after his death in 1222 were given charge of his body which, as that of an excommunicate, could not be buried in hallowed ground. His body stayed outside the priory of the Hospitallers while Raymond VII petitioned successive popes to permit it to be buried in the chapel. It was still there in the fourteenth century, but by the sixteenth, ‘rats had destroyed the wooden coffin and Raymond’s bones had disappeared’.254