seven

Outremer

The disillusion in Europe that followed the fiasco of the Second Crusade obliged the Latins in the Holy Land to reach the kind of accommodation with the infidel that would have seemed sacrilegious to the previous generation of crusaders. This was also the consequence of a process of cultural acclimatisation that had occurred over half a century of living in the East. The early crusaders had expected to encounter wild savages and depraved pagans in Syria and Palestine: but those who had remained in the Middle East had been obliged to recognise that the culture of Arab Palestine – Muslim, Christian, and Jewish – was more evolved and sophisticated than that at home.

Some had quickly adopted Eastern customs. Baldwin of Le Bourg, having married an Armenian wife, took to wearing an Eastern kaftan and dined squatting on a carpet; while the coins minted by Tancred showed him with the head-dress of an Arab. The Damascene chronicler and diplomat, Usamah Ibn-Munqidh, describes a Frankish knight reassuring a Muslim guest that he never allowed pork to enter his kitchen and that he employed an Egyptian cook.159

The Franks employed Syrian doctors, cooks, servants, artisans, labourers. They clothed themselves in eastern garments, included in their diets the fruits and dishes of the country. They had glass in their windows, mosaics on their floors, fountains in the courtyards of their houses, which were planned on the Syrian model. They had dancing girls at their entertainments; professional mourners at their funerals; took baths; used soap; ate sugar.160

Coming from a cold climate where fresh produce was unavailable during winter, and where even the potato was as yet unknown, the encounter not just with sugar but also with figs, pomegranates, olives, rice, hummus, peaches, oranges, lemons and bananas, the spices indigenous to the region, and delicacies such as sherbet whose names have since entered the gastronomic vocabulary of the West, must have convinced the crusaders that it was not just in a spiritual sense that this was the promised land. Certainly, the hot climate was debilitating and indeed in some cases proved fatal; but among those who survived, many adopted the scented, sensuous lifestyle which they had thought effete in the Byzantines.

Not only were the Franks softened by the style of life they encountered in Syria and Palestine; they were also obliged to reach a modus vivendi with the Muslims who remained a majority of the population. As long as they paid their taxes, the Frankish overlords were prepared to permit the Muslim communities to choose their own administration. As in the reconquered territories in Spain, there were insufficient Christian immigrants to replace the Muslims; it was therefore important for the fief-holders to persuade them to stay. A baron’s wealth depended upon their prosperity. Nor did his principal revenue come from the land, as in Europe. ‘The Holy Land was an urbanised area par excellence’161 and a baron’s income came from rents on properties, tolls, licences for public baths, ovens and markets, port dues and levies on goods.162

By the standards of the day – and even by those of today – these charges and exactions were not severe: the tax on a peasant’s produce (terrage) was fixed at around one-third. Although the Muslims’ first loyalty was always to Islam, there is evidence that they were not dissatisfied with Latin rule. The rule of Frankish overlords was in fact lighter than in the former period of Muslim domination.163 The Franks’ respect for feudal law contrasted favourably with the capricious demands of Muslim princes. Certainly, Muslims were second-class citizens; they were forbidden to wear Frankish dress; but they had their own courts and officials. Conversion to Christianity brought with it full civil rights and led to assimilation into the Christian Syrian population. Among the Franks themselves there were no serfs, a fact that distinguished it from the feudal societies in western Europe. ‘Though hierarchic, it was a society of free men, where even the poorest and most destitute were not only free, but enjoyed a higher legal standing than the richest among the conquered native population.’164

Despite the anti-Semitic atrocities that had accompanied the First Crusade, there was a large measure of tolerance of the Jews in the crusader states: they were treated much better than their counterparts in western Europe and could practise their religion in relative freedom.165 Jewish pilgrimages to the holy places and Jerusalem became more frequent from as far off as Byzantium, Spain, France and Germany.166 No attempt was made by the Catholic Latins to convert the Muslims or the Jews: there was a remarkable lack of any kind of missionary activity. The religious disputes that did take place were rather between the Catholics and Orthodox Christians, exacerbated by Latin rivalry with Byzantium; or between both Catholic and Orthodox and the Jacobite, Armenian, Nestorian and Maronite churches.

The indigenous population – both Muslim and Christian – also benefited from the prosperity that came with the increase in trade. Prior to conquest by the crusaders, a small flow of commerce in oriental products such as silks and spices found its way to the West via the merchants of Amalfi. With the capture of the ports on the Mediterranean coast and the granting of concessions to the growing maritime powers from Italy – Venice, Genoa and Pisa – considerable trade was stimulated with the Muslim hinterland financed by a Latin currency, the besant – ‘the first Christian coin in wide circulation, struck a hundred years before the florins and ducats of Italy’.167

The Templars benefited from this prosperity through their fiefs, and they also came to extend a tolerance to the indigenous Muslims which shocked those newly arrived from Europe. There was a celebrated incident when Usamah Ibn-Munqidh came to Jerusalem to negotiate a pact against Zengi, the Saracen governor of Aleppo.

When I was visiting Jerusalem, I used to go to the al-Aqsa mosque, where my Templar friends were staying. Along one side of the building was a small oratory in which the Franj had set up a church. The Templars placed this spot at my disposal that I might say my prayers. One day I entered, said Allahu akbar and was about to begin my prayer, when a man, a Franj, threw himself upon me, grabbed me, and turned me toward the east, saying, ‘Thus do we pray.’ The Templars rushed forward and led him away. I then set myself to prayer once more, but this same man, seizing upon a moment of inattention, threw himself upon me yet again, turned my face to the east, and repeated once more, ‘Thus do we pray.’ Once again, the Templars intervened, led him away, and apologised to me, saying, ‘He is a foreigner. He has just arrived from the land of the Franj and he has never seen anyone pray without turning to face the east.’168

Despite his friendship with the Templars, the attitude of Usamah towards the Franks was one of contempt. He ridicules trial by combat and trial by ordeal as a form of justice, and is scornful of their medical practices. In fact, the Franks developed a pragmatic approach towards disease: the kind of religious hysteria provoked by the epidemic in Antioch during the First Crusade was not repeated, ‘perhaps because prayer and penance had not worked’; and subsequently the crusaders ‘seem to have approached medicine in a very practical way, and may have had less to learn from the native practitioners than had been assumed’.169 By and large, the only Latin quality deemed worthy of respect by Muslims was their military prowess. They despised the Christians’ culture and beliefs. ‘According to the Bahr al-Fava‘id, the books of foreigners were not worth reading … [and] anyone who believes that his God came out of a woman’s privates is quite mad; he should not be spoken to, and he has neither intelligence nor faith.’170

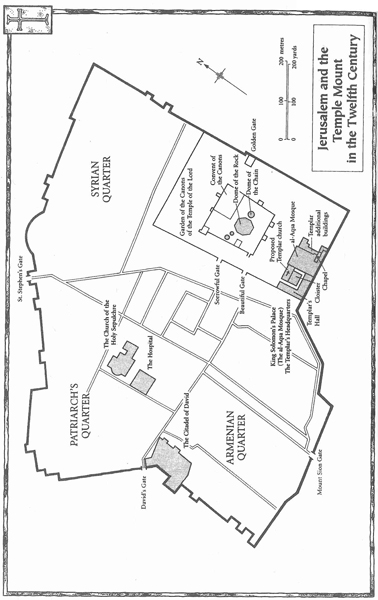

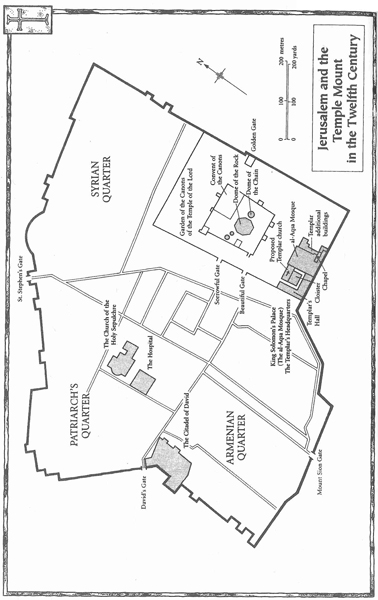

This contempt for the religious beliefs of the enemy was, by and large, returned. The Templars might have permitted their Muslim guest to pray in their chapel, but they used the al-Aqsa mosque as an administrative centre and a store. Theoderich, a German monk on pilgrimage to Jerusalem in the 1170s, calling it the palace of Solomon, describes how it was used for ‘stores of arms, clothing and food they always have ready to guard the province and defend it’. Below the mosque were the Templars’ stables ‘erected by King Solomon’ with space, he estimated, for ten thousand horses. Adjacent to the al-Aqsa was the palace originally occupied by King Baldwin I, and a number of other:

houses, dwellings and outbuildings for every kind of purpose, and it is full of walking-places, lawns, council-chambers, porches, consistories and supplies of water in splendid cisterns … On the other side of the palace, that is on the west, the Templars have built a new house, whose height, length and breadth, and all its cellars and refectories, staircase and roof are far beyond the custom of this land … There indeed they have constructed a new Palace, just as on the other side they have the old one. There too they have founded on the edge of the outer court a new church of magnificent size and workmanship.171

It is difficult to know how many lived in this compound. At most, there were probably around 300 knights in the Kingdom of Jerusalem and around 1,000 sergeants.172 There would have been an irregular and indeterminate number of knights serving for a set period in the Order, and there were the Templar Turcopoles – native Syrian light cavalry employed by the Order. Beyond this, there would been a large number of auxiliaries of one sort or another – armourers, grooms, blacksmiths, stonemasons and sculptors: Templar sculptors ‘prepared the most elaborately decorated of all royal tombs’ for King Baldwin IV.173 The Templars therefore participated in the extraordinary boom in building that took place in the Holy Land under the crusaders – fortresses, palaces and above all churches: ‘not even Herod built as much’.174 Among the major architectural accomplishments were the new Church of the Holy Sepulchre, dedicated in 1149, and the redecoration of the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem – ‘a milestone in crusader artistic development because many artists from a variety of backgrounds took part’.175

Despite this cultural refinement, and the sensuous blandishments that came with the climate, the Templars appear to have kept to their Rule and retained a quasi-monastic way of life. When not in the field, the Templars followed the same kind of timetable as Benedictine or Cistercian monks. At four in the morning, they rose for matins after which they went to take care of their horses before returning to bed. The further offices of Prime, Terce and Sext preceded their breakfast which, like all their other meals, was eaten in silence while listening to a reading from the Bible. At 2.30 p.m. there was Nones and their evening meal followed Vespers which was at 6.00 p.m. They retired to bed after Compline and remained silent until the next day. Orders were given after each office except Compline. When in the field, every attempt was made to follow the same regime.

There were more than six hundred clauses in the Templar statutes, some elaborations on those of the primitive Rule, others drawn up to deal with questions that had arisen since the Council of Troyes. The original seal of the Order had shown two knights riding on a single horse. Now, the Master was permitted to have four horses, and could have in his entourage one chaplain, one clerk, one sergeant and one valet with a horse to carry his shield and lance. He should also be accompanied by a blacksmith, an interpreter, a turcopole and a cook. There were clear limits to his powers: he was not to have the key to the treasury, and he could only lend large sums with the consent ‘of a group of the worthy men of the house’. Limits were also set to his munificence: he could give a noble friend of the house a gold or silver goblet, a squirrel-hair robe or some other item worth no more than one hundred besants, and these gifts should only be made with the consent of his companions and for the benefit of the house.

The Rule reflects some of the prejudices of the period; for example, despite the commitment to humility, it became necessary by the mid-twelfth century for a Templar knight to be ‘the son of a knight or descended from the son of a knight’ (rule 337). The white habit that had been chosen to symbolise purity now became a mark of prestige: the tunics of the squires and sergeants were brown or black. The knights ate at the first sitting, the sergeants and squires at the second. Given the fact that almost none of the knights or sergeants could read, it seems likely that most of the statutes simply reflected the practices that had evolved, and were picked up by new recruits like new boys at a public school. And like the punishments meted out in public schools in the past, the penances inflicted on erring Templars seem savage – whipping, being put in irons, or being obliged to eat like a dog off the floor. Such penances were similar to those imposed on monks, and were normal for the time.

Every aspect of the Templar’s daily life was regulated down to the smallest detail. When he should eat, how much he should eat, how he should comport himself while eating – even how he should cut cheese (371) – is specified in the Rule. He could not rise from table without permission unless he had a nosebleed, there was a call to arms (and then he had to be sure that the call was made by a brother or ‘a worthy man’), a fire or a disturbance among the horses. He had no private property: ‘all things of the house are common, and let it be known that neither the Master nor anyone else has the authority to give a brother permission to have anything of his own…’ If any money was found in a brother’s possession on his death, he was not to be buried in hallowed ground.

The care of horses was clearly of cardinal importance: the number allocated to the Master is stated in the first statute and horses are mentioned in around a hundred of those that follow. There were several different sorts: warhorses for the knights; lighter, swifter steeds for the turcopoles; palfreys; mules; packhorses and rouncies – transport for men-at-arms. Each knight was allowed his own horse, while the others were kept in a general pool in the charge of the Marshal of the Order. Horses were bred on stud farms both in the Kingdom of Jerusalem and in western Europe – for example, at the Temple commandery at Richerenches in northern Provence. There were precise regulations for the care of the horses, and one of the only excuses for missing prayers was taking a horse to the blacksmith for shoeing.176

Few clauses in the Rule pertain to training: a knight was expected to be adept at mounted combat before he joined the Order. Given the weight of the accoutrements of combat, each must have been immensely strong. A knight was expected to bring his own horse and equipment. If he was serving as a confrère for a limited term, they would be returned when it ended or, if his horse died in Templar service, he would be given another from the pool. True to the spirit of Bernard of Clairvaux, saddles and bridles were not to be adorned; permission had to be obtained to race and the placing of wagers on the outcome was forbidden.

Although the way of life suggested by the Templar Rule is imbued with Christian religiosity, and the monastic practices given an equal standing to the military regulations, there is a shift in emphasis in comparison with the primitive Rule from the quest for individual salvation to a regimental esprit de corps. ‘Each brother should strive to live honestly and to set a good example to secular people and other orders in everything…’ (340): the unspecified ‘other orders’ were principally the Hospitallers and later the Teutonic knights. The Temple’s two-pointed black-and-white banner, the confanon baucon, was their rallying point in battle. It was held by the Marshal and ten knights were assigned to guard it, one of whom kept a spare banner furled on his lance. While this banner was still held aloft, no Templar could leave the field of battle. If a knight was cut off from his contingent, he was allowed to regroup around the Hospitaller or another Christian banner (167).

The monastic vow of obedience was invaluable in a military context: severe penalties were imposed on a knight who succumbed to the impetuosity so common among the Frankish knights and charged at the enemy on his own initiative. The only occasions upon which he was permitted to break rank were to make a brief sortie to ensure that his saddle and harness were secure or if he saw a Christian being attacked by a Saracen. In any other circumstances, the punishment was to be sent back to the camp on foot (163).

In the same way no distinction was made between military and religious transgressions. Of the nine ‘Things for which a Brother of the House of the Temple may be Expelled from the House’, four were sins that had nothing as such to do with life under arms: simony, murder, theft and heresy. Revealing the proceedings of the Temple chapter, conspiracy between two or more brothers, and leaving a Templar house other than by the prescribed gates are infringements that would have applied to any monastic institution. Only the punishment of cowardice and desertion to the enemy relate specifically to conditions of war.

Thus the regimental ethos was never distinct from the Christian ethos of the Temple as a religious community. The regulations governing fasts and feast-days, the saying of office and prayers for the dead, were quite as precise as those concerned with saddles and bridles. The Templars showed a particular devotion to Mary, the Mother of Jesus: ‘And the hours of Our Lady should always be said first in this house … because Our Lady was the beginning of our Order, and in her and in her honour, if it please God, will be the end of our lives and the end of our Order, whenever God wishes it to be’ (306). A number of beliefs arose which linked Mary with the Temple: for example, it was said that the Annunciation had taken place in the Temple of the Lord (the Dome of the Rock) and a stone on which Mary rested was outside the Templar fortress of Castle Pilgrim. There were Lady chapels in many of the Templar churches and a number of their houses, such as that at Richerenches, were dedicated to Mary: Richerenches was referred to by a number of donors not as the Temple but as ‘the house of the Blessed Mary’.177

One of the more revealing clauses in the Templar Rule (325) concerns the wearing of leather gloves, which was allowed only to the chaplain brothers, ‘who are permitted to wear them in honour of Our Lord’s body, which they often hold in their hands’; and to the ‘mason brothers … because of the great suffering they endure and so that they do not easily injure their hands; but they should not wear them when they are not working’.178 The number of these mason brothers is not known, but because of the importance of the fortresses in Outremer their skills would have been highly valued. A castle built by the Templars or the Hospitallers ‘showed itself as a fortress without, while within it was a monastery’.179 With a relatively small garrison, a well-provisioned castle could withstand a siege of a considerable army. Should that army ignore it, it could make sorties to attack its rear. Sieges tied down large armies which could often only be held together for a limited period of time. Non-mercenary troops had to think of the harvest and the protection of their families from marauders who took advantage of their absence: and in the case of the Franks, the feudal levy was restricted to a period of forty days. The conflict between Christians and Muslims in the Holy Land ‘rarely afforded the spectacle of two armies bent on mutual destruction; the true end of military activity was the capture and defence of fortified places’.180

A prime example was the great fortress of Ascalon, held by the Fatimid caliphs in Egypt. Supplied by land across the Sinai peninsula and by sea from Alexandria, it protected the coastal road leading to Egypt and provided a base for raids against Christian settlements. In an attempt to contain Ascalon, King Fulk had surrounded it with a ring of fortresses at Ibelin, Blanchegarde and Bethgibelin: Bethgibelin had been assigned to the Hospitallers and Ibelin to a knight, probably of Italian extraction, who came to be known as ‘Balian the Old’.

In 1150, the encirclement was completed with the construction of a fortress on the ruins of Gaza, the city to the south of Ascalon where in the Old Testament Samson had been imprisoned by the Philistines. This was given to the Templars, who successfully repelled an attempt by the Egyptians to take it. The south of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was now secure and King Baldwin III could proceed to besiege Ascalon itself. In January 1153, he assembled his forces before the city, including a force of Hospitallers under their Master, Raymond of Le Puy, and Templars under Bernard of Trémélay: Bernard was a Burgundian from near Dijon, no doubt known to Bernard of Clairvaux, who had been chosen to replace Everard des Barres as Grand Master when, the year before, Everard had retired to Clairvaux as a monk.

Supplied from the sea, the Egyptians in Ascalon could not be starved into surrender: the city had to be taken by assault. The Franks built a wooden tower that rose higher than the ramparts which was positioned at the sector manned by the Templars. On the night of 15 August, a group of the defenders made a sortie from the city and set fire to this tower; but when it was ablaze, the wind changed direction and blew the flames against the walls. The masonry cracked and crumbled and part of the wall collapsed. Bernard of Trémélay, the Master of the Templars, seized this opportunity and led forty of his men through the breach: however, the main force failed to follow them and the Templars were surrounded and cut down by the defenders. The next day, their headless bodies were dangled from the walls – among them, that of the Grand Master, Bernard of Trémélay.

In his account of this misfortune, the Latin chronicler, William of Tyre, wrote that the Templars had fallen victim to their own greed: Bernard of Trémélay had ordered his knights to prevent anyone else from joining them in this initial assault because he wanted to reserve for his Order the glory of taking the city and a lion’s share of the booty. The most recent research suggests, however, that ‘William’s version of this incident seems to be distorted,’ being based on the defensive accounts of the Latin commanders who had been criticised ‘for failing to follow the Templars into the breach’:181 however, the calumny was widely circulated and damaged the Order’s reputation in western Europe.

The loss of the Templars did not affect the outcome of the siege. On 19 August the city surrendered to King Baldwin and was evacuated by the Egyptians, its inhabitants being permitted to take their moveable belongings with them. Prodigious amounts of treasure and supplies of arms were left behind. For King Baldwin, Ascalon was a remarkable prize and its capture marked the high point of his reign. It was given as a fief to his brother Amalric, Count of Jaffa. The mosque was consecrated as a cathedral dedicated to the apostle Paul.

To replace Bernard of Trémélay, the Templar chapter elected Andrew of Montbard, the uncle of Bernard of Clairvaux who until then had held the office of Seneschal of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Despite the loss of forty knights, they continued to garrison their fortress at Gaza, using it as a base from which to patrol the routes taken by caravans travelling between Cairo and Damascus. In 1154, the year after the fall of Ascalon, a Templar contingent ambushed an Egyptian force that was escorting the Egyptian Vizir, Abbas, and his son Nasir al-Din – both fleeing with a large amount of treasure after the failure of a coup against the Caliph. Abbas was killed in the attack but Nasir al-Din was taken prisoner by the Templars. It was later claimed by William of Tyre that in their custody he learned Latin and was ready to become a Christian but that this was not thought a good enough reason for the Templars to forgo the substantial sum of money offered for him by his enemies in Egypt. He was duly returned to the partisans of the Caliph and once in Cairo was first ‘personally mutilated’ by the Caliph’s four widows,182 then ‘torn to pieces by the mob’.183

Such charges of greed against the Templars were made by chroniclers who had an axe to grind, such as William of Tyre and Walter Map, and are difficult either to verify or to refute from this distance in time. It should also be borne in mind that booty was considered a legitimate form of income and provided the means to further the work of their Order. The costs incurred by the military orders were stupendous: the Hospitallers faced bankruptcy in the 1170s.

* * *

Andrew of Montbard died in 1156 after only three years as Grand Master. In 1158, his successor, Bertrand of Blanquefort, with 87 brothers and 300 secular knights, was ambushed by a Saracen force as they passed down the Jordan valley and Bertrand captured.

Because of the mountainous terrain in Syria and Palestine, and because the Saracens’ intelligence was generally better than the Christians’ (they used carrier pigeons and the rural population was mostly Muslim), it was difficult to guard against setbacks of this kind. Despite their occasionally insensate courage, no doubt inspired by confidence that God would weigh in on their side, the Templars in particular, and the Frankish knights in general, became more circumspect in battle as time went on. They had learned from experience that the Saracens were also skilled fighters who often exploited the Franks’ courage with their guile. They appreciated ‘that they must stand firm in the face of archery and encirclement, ignore the temptation offered by … simulated flight, preserve their solidarity and cohesion until they could choose the moment at which to deliver their charge with the certainty of striking into the main body of the enemy…’184 Gone was the wild impetuosity of the early crusaders. ‘Of all men,’ wrote the Damascene diplomat Usamah, ‘the Franks are the most cautious in warfare.’

The same circumspection was apparent in the diplomacy of King Baldwin III, the most sagacious of the kings of Jerusalem. His father Fulk had been killed out hunting when Baldwin was still a child and, although crowned king in 1143 at the insistence of the barons, he had only broken loose from the tutelage of his mother Melisende with great difficulty. The eldest of the three formidable daughters of King Baldwin II of Jerusalem, Melisende, like her sister Alice in Antioch, had refused to accept that as a woman she lacked the competence to rule. In the 1140s she had brought the Kingdom of Jerusalem to the brink of civil war in a struggle with her husband, Fulk of Anjou, preferring her childhood friend, the handsome Lord of Jaffa, Hugh of Le Puiset, to the ‘short, wiry, red-haired, middle aged man whom political advantage had forced upon her’.185 It was also said that, as a favour to her sister Hodierna, she had commissioned the poisoning of Alfonso-Jordan, the young Count of Toulouse, who had died suddenly at Caesarea at the time of the Second Crusade: he had a better hereditary claim to the County of Tripoli than Hodierna’s husband, Count Raymond.

In 1152 it was the turn of Melisende’s son, King Baldwin III, to antagonise his mother when, nine years after his coronation, he tried to govern on his own. Melisende was no more willing to abdicate her share of power to her son than she had been to her husband. Their differences led to a breach with, first, a de facto division of the kingdom and, subsequently, open conflict between mother and son. Besieged by Baldwin’s forces in the citadel in Jerusalem, Melisende was eventually persuaded to surrender and live with her sister, the Abbess Joveta, in her convent in Bethany.

Both Melisende’s contemporaries and later historians have been impressed by this ‘truly remarkable woman who for over thirty years exercised considerable power in a kingdom where there was no previous tradition of any woman holding public office’.186 William of Tyre judged that ‘she was a very wise woman, full experienced in almost all spheres of state business, who had completely triumphed over the handicap of her sex so that she could take charge of important affairs … she ruled the kingdom with such ability that she was rightly considered to have equalled her predecessors in that regard.’ Baldwin himself came to recognise her qualities and, his confidence bolstered by the capture of Ascalon, treated his mother with considerable respect and involved her in state affairs.

Even before the fall of Ascalon, she was summoned to join the principal dignitaries of Outremer to consider the future of her niece Constance, the widowed Princess of Antioch. Three years before, her handsome husband Raymond of Poitiers, the uncle and reputed lover of Eleanor of Aquitaine, had been killed while on a raid to the north of his principality, and it was deemed vital that Constance should marry a credible leader in war: the widower brother-in-law of the Byzantine Emperor, a Norman, John Roger, was proposed. It was also hoped that she might reconcile her sister Hodierna to her husband, Count Raymond II of Tripoli, but in the event she failed on both counts: Constance refused to consider the middle-aged John Roger and Raymond II was murdered as he rode into his city of Tripoli.

* * *

Raymond’s murderer was a member of a fanatic sect of Shia Muslims, the Assassins, who, like the Sicarii among the Jewish Zealots, pursued their objectives by the covert killing of their enemies. Their name comes from the word hashish, the narcotic which, according to the crusaders, induced a trance which made the killers oblivious to danger. The Shia were originally a political faction who believed that Ali, Muhammad’s son-in-law, was his true successor; but after the death of Ali in 661 it had developed into a radical Islamic sect dedicated to the overthrow of the Sunni caliphate in Baghdad. Persecuted for their beliefs, the Shia developed mystical notions, revolutionary methods and messianic aspirations, and split into further factions, the most radical being the Ismailis who ‘elaborated a system of religious doctrine on a high philosophic level and produced a literature which, after centuries of eclipse, is only now once again beginning to achieve recognition at its true worth’.187

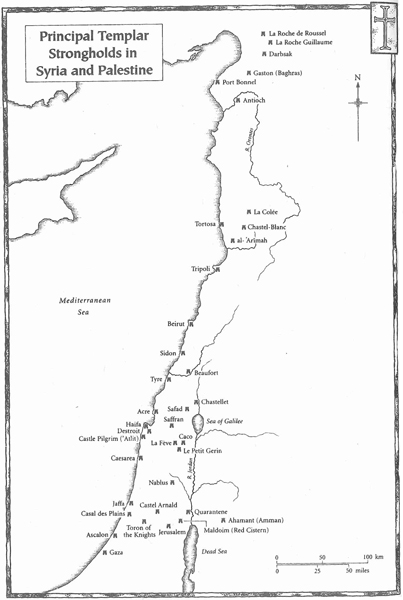

Central to the Ismaili system was the idea of the Imam, the inspired and infallible descendant of Ali and Fatima through Ismail. He had access to special knowledge and was to be obeyed without question. In the early tenth century, a claimant to this descent seized power in North Africa and established the Fatimid (after Fatima) caliphate in Cairo in rivalry to the Sunni caliphate in Baghdad. By the time of the crusades the Fatimid empire was in decline. However, in the Elburz Mountains in northern Persia, overlooking the shore of the Caspian Sea, a group of intransigent Ismailis under Hasan-Sabbah established themselves in the impregnable fortress of Alamut. From here Hasan sent out his devotees to murder the Sunni sultans and their vizirs. He also sent missionaries to Syria to win converts but also to take fortresses as bases for his campaign of terror. In 1133 the Assassins purchased the castle of Qadmus from the Muslims who had taken it from the Franks. Shortly afterwards, they acquired al-Kahf; in 1137 they took Khariba from the Franks; and in 1142 the major stronghold of Masyaf was taken from the Damascenes. Other fortresses fell into their hands at around the same time and brought them face to face with the castles of the military orders at Kamel, La Colée and Krak de Chevaliers, and in the coastal cities of Valania and Tortosa.

The hatred of the Assassins for their Muslim enemies made them amenable to forming alliances with the Franks. At the Battle of Inab in 1149, an Assassin leader, Ali ibn-Wafa, died fighting alongside Raymond of Poitiers: yet only three years later a member of the same sect murdered Raymond II of Tripoli for no known reason. Since Queen Melisende was suspected of ordering the poisoning of the young Alfonso-Jordan, Count of Toulouse, it is not impossible that she also commissioned the Assassins to get rid of Hodierna’s difficult husband.

In this way, theological differences among the followers of Muhammad, combined with the passions of strong-willed women, came to affect the destiny of the Latins in Outremer. The most fateful instance of the latter came in 1153 when Constance returned to the principality of Antioch. Now it became clear why she had turned down the bridegroom proposed by the King of Jerusalem and Emperor of Byzantium. Her eye had fallen on another man – a French knight, Reginald of Châtillon. Reginald was the younger son of Geoffrey, Count of Gien-sur-Loire, and took his title from Châtillon-sur-Loire. Thought to have come east with King Louis VII on the Second Crusade, he had remained in the retinue of King Baldwin III. To judge from his subsequent behaviour, he was ruthless, audacious, exceptionally brave and almost certainly handsome – qualities that won the love of Constance and led to the mésalliance of the century: it was quite astonishing, wrote the Archbishop of Tyre, ‘that such a famous, powerful and well-born woman, the widow of such an outstanding husband, should condescend to marry a kind of mercenary knight’.188

Baldwin III, acknowledging Reginald’s abilities as a soldier, recognised him as Prince of Antioch. So too, albeit with reluctance, did the Byzantine Emperor Manuel in exchange for Reginald’s help against the Armenians in Cilicia. Aided by the Templars, Reginald marched north and took the port of Alexandretta which he gave to the Templars. He now quarrelled with the Emperor Manuel over the subsidies he felt were his due. Encouraged by the Templars, he made peace with the Armenians and decided to recover from the Byzantines what he felt was his due by plundering the island of Cyprus. He needed funds for this expedition and decided to extract them from Aimery, the Latin Patriarch of Antioch, whom Reginald loathed because Aimery had vociferously opposed his marriage to Constance. Aimery refused to give him any money, whereupon Reginald had him thrown into prison, brutally beaten, then pinioned on the roof of the citadel with honey rubbed into his wounds to attract the flies.

This treatment had the desired effect: the Patriarch gave over his money to Reginald who used it to equip a fleet. In the spring of 1156, with the Armenian King Thoros, he landed with an army on Cyprus, until then one of the most peaceful provinces of the Byzantine Empire and the source of supplies to the starving army of the First Crusade. Defeating and capturing the island’s governor, the Emperor’s nephew John Comnenus, and its military leader, Michael Branas, the army of Reginald and Thoros proceeded to pillage the island ‘on a scale that the Huns and Mongols might have envied’.189 Indifferent to the fact that the Cypriots were Christian, their women were raped, their children and old people murdered, their churches and convents robbed, their cattle and crops sequestered. The prisoners either bought their own freedom, were taken in chains to Antioch, or were mutilated and sent to Byzantium as a living gesture of defiance and disdain.

Reginald’s brutal and piratical behaviour caused consternation in Jerusalem. On hearing of the incarceration of the Patriarch Aimery, King Baldwin III sent emissaries to insist upon his release and, once it was secured, to bring him to Jerusalem. The plunder of Cyprus was even more grave because it placed in jeopardy Baldwin’s policy of an alliance with the Byzantine Empire. To seal the pact, Baldwin had been promised a Byzantine princess, Theodora, the Emperor’s fifteen-year-old niece, with a huge dowry that would replenish the depleted treasury of the kingdom. The wedding took place in Jerusalem in 1158.

The diplomatic objective of this alliance was Byzantine assistance against Nur ed-Din and, for the Emperor Manuel, the punishment of Thoros and Reginald. At the approach of a powerful Byzantine army, Thoros fled into the mountains while Reginald made an abject submission. Before an assembly of visiting princes and courtiers gathered before the walls of Mamistra, Reginald advanced, barefooted and bareheaded, and prostrated himself in the dust before the Byzantine Emperor. After savouring his enemy’s humiliation, and imposing certain conditions, Manual permitted the penitent to rise and return to Antioch.

This degradation of Reginald, although recognised by the Latins as well deserved, was felt as a humiliation to them all. Baldwin had hoped that Reginald would not be so easily forgiven. For Manuel, however, it was better to have Antioch ruled by a man who, when Manuel made his triumphal entry into the city, was prepared to walk beside him leading his horse than another prince less amenable and certainly less visibly his vassal. Though Manuel developed a warm personal regard for Baldwin, his nephew by marriage, the two men’s strategic priorities were not the same, as Manuel demonstrated by making a pact with the Latins’ arch-enemy, Nur ed-Din, against the Seljuk Turks in Anatolia. To the Latins, this was yet another instance of Greek perfidy; however, among the benefits of this treaty to the Latins was the release of Christian captives, among them the Master of the Temple, Bertrand of Blanquefort.

Any expectation among the Christian princes that Reginald of Châtillon would have learned by his mistakes would soon be shown to be misplaced. In November 1160, Reginald had set out on a raid on the herds of cattle mostly owned by Christian Syrians. On his way back to Antioch with his four-footed booty, he was ambushed by a Muslim force under the governor of Aleppo. Reginald was captured and taken on the back of a camel to Aleppo. No one came forward to offer a ransom. He was to remain incarcerated for the next sixteen years.

* * *

In February 1160, King Baldwin III died at the age of only thirty-three – a man of great charm, intelligence and learning who was mourned even by his Muslim subjects and by the governor of Aleppo, Nur ed-Din. He had no heir: his wife, Queen Theodora, was still only sixteen and now retired to Acre, given to her as part of the marriage settlement.

Baldwin was succeeded by his brother Amalric, aged twenty-five, as tall and good-looking as Baldwin but lacking both his learning and his charm. Amalric, who had been Lord of Jaffa and Ascalon, was content to leave the Byzantines to protect the northern frontiers of his kingdom and directed his attention south towards Egypt. There, as a result of a sequence of sanguinary coups and counter-coups, the Fatimid caliphate was disintegrating and the government of the country was in confusion. Few of the cities in Sinai or the Nile Delta were fortified and the potential booty was stupendous; but there was also the more pressing strategic reason for moving against Cairo; for if the Latins did not fill the vacuum, then Nur ed-Din surely would.

In 1160, a projected invasion by Baldwin III had been bought off by the promise of a yearly tribute that was never paid. Using this default as a pretext, Amalric led a force into Egypt in the autumn of 1163 which included a large contingent of Templars; but by breaching dykes in the Nile Delta the Egyptians forced the Franks to retire. In the following year, to pre-empt a take-over in Cairo by Nur ed-Din’s protégé, Shawar, Amalric was back in Egypt: he reached an agreement with Shawar that both armies should retire.

Taking advantage of Amalric’s absence, Nur ed-Din had attacked the principality of Antioch, laying siege to the fortress of Harenc. Bohemond, the young son of Constance and Raymond of Poitiers, now reigning as Prince Bohemond III, set off with a combined Antiochene, Armenian and Byzantine army to relieve Harenc. In this force there was a contingent of Templar knights and their accompanying sergeants, squires and turcopoles. At its approach, Nur ed-Din raised the siege and retired. Against the advice of his more experienced companions, Bohemond went after this much larger army. He caught up with them on 10 August. Using their favourite tactic, the Muslims feigned retreat. Bohemond and his knights charged after them, were ambushed and either taken prisoner or killed. Of the Templar knights, sixty fell in the battle and only seven escaped.

This setback was no doubt one of the factors that led the Templars to prefer their own judgement on military matters to that of the Latin princes. Although committed by their statutes to the defence of the Holy Land, the Grand Master was subject to the Pope, not the King of Jerusalem. To Amalric, however, the autonomy of the military orders hampered his conduct of the war against Islam. In 1166, a cave-fortress in TransJordan, garrisoned by the Templars and said to be impregnable, was besieged by the forces of Nur ed-Din. It had probably formed part of the bequest made by Philippe of Nablus, the Lord of Oultrejourdain, when he joined the Order in January 1166.

On hearing of the siege, Amalric assembled an army to relieve it but on reaching the River Jordan he met the twelve Templars who had surrendered the stronghold without a fight. Amalric was so angry that he had the knights hanged. This episode, recorded in the history of William of Tyre, could well have been one of the factors that soured relations between the Temple and the King. In 1168, when Amalric decided upon a full-scale invasion of Egypt, he was supported by the Grand Master of the Hospital, Gilbert of Assailly, and most of the lay barons, but the Grand Master of the Temple, Bertrand of Blanquefort, refused point-blank to take part.

Low motives were ascribed to the Templars for this decision: it was said that it was because the plan had been promoted by their rivals, the Hospitallers; or that they had profitable financial dealings with the Italian merchants who traded with Egypt. But the near bankruptcy of the Hospital, which no doubted prompted Gilbert of Assailly to try and recoup its losses on the Nile, was also an object lesson to the Temple which had sustained heavy losses in Antioch and was fully committed to the defence of the Holy Land, both in the north in the Amanus march and in the south around Gaza. There was also Amalric’s treaty with Shawar: newcomers from France, such as Count William IV of Nevers, who counselled King Amalric, might not understand the value of keeping faith with an infidel, but the Templars already had sufficient appreciation of local conditions to recognise that diplomacy could on occasion be more efficacious than force.

A further example of the Templars’ independence, and their willingness to thwart the plans of the King, came in 1173 when Amalric entered into negotiations with the chief of the Assassins in Syria, known to the crusaders as ‘The Old Man of the Mountain’. This was Sinan ibn-Salman ibn-Muhammad who came originally from a village near Basra in Iraq. A protégé of Hasan, the Assassin Imam in Alamut, Sinan became the ruler of the Assassins’ enclave in Syria and pursued a policy of his own. For thirty years, every ruler in both the Islamic caliphates and every Christian state was at risk from a murderous attack by one of Sinan’s Ismaili devotees: exempt were the Grand Masters of the military orders because the Assassins realised that if one was killed there would always be another to take his place.

On the whole, because they were the enemies of their enemies, the Assassins were tolerated by the Franks. The Templars, who might have moved against them from their bases in Tortosa, La Colée and Chastel-Blanc, were paid an annual ‘tribute’ of 2,000 besants by the Assassins to leave them alone. In the 1160s, the millennial tendencies inherent in Ismaili teaching exploded when Hasan, the leader in Almut, abrogated the Law of Muhammad and proclaimed the Resurrection. Sinan promulgated the new dispensation in Syria and, like the Anabaptists in Münster many centuries later, the elect then gave themselves over to an orgy of debauchery. ‘Men and women mingled in drinking sessions, no man abstained from his sister or daughter, the women wore men’s clothes, and one of them declared that Sinan was God.’190

It was some years after Hasan’s abrogation of Islam that Sinan sent word to King Amalric and the Patriarch of Jerusalem that he was interested in conversion to faith in Christ. To this end Hasan sent an envoy, Abdullah, to negotiate a settlement with the King. After a satisfactory conclusion to these preliminary talks, Abdullah started on his journey back from Jerusalem to Massif with a safe-conduct from King Amalric. Shortly after passing Tripoli, his party was attacked by a group of Templars led by a one-eyed knight, Walter of Mesnil.

This outrage infuriated King Amalric who ordered the arrest of the culprits. The Grand Master of the Temple was now Odo of Saint-Amand who had replaced Philip of Nablus in 1168. Odo had been a royal official, holding a number of important posts before joining the Order: he had been a captive of the Muslims between 1157 and 1159. His choice as Grand Master had almost certainly been to further good relations with King Amalric; but now Odo insisted upon the legal rights accorded to the Templars by the papal bull Omne datum optimum. His knights were exempt from secular jurisdiction: Walter of Mesnil had been punished by the Order for his transgression and it would now send him for final judgement to Rome. Ignoring these niceties, Amalric rode to Sidon where the Templar chapter was in session, and seized the offending Walter of Mesnil. He was imprisoned in Tyre and Sinan was persuaded by Amalric’s profuse apologies that the attack on his ambassador was not of his doing. However, the incident irrevocably alienated the King from the Temple and his plan to petition the Pope and the European monarchs to dissolve the Order was only frustrated by his death in 1174.

What was behind the attack on the Assassin ambassador by Walter of Mesnil? Odo of Saint-Amand never took responsibility for his action; but given the vow of obedience taken by each brother knight it seems improbable that Walter was acting wholly on his own initiative. The motive given by the contemporary chronicler, William of Tyre, is greed: the Templars were unwilling to lose the annual tribute of 2,000 besants which would have lapsed with the Assassin’s conversion. A later chronicler, Walter Map, suggests that they were afraid that peace would destroy their raison d’être, killing the Assassins’ envoy ‘lest (it is said) the belief of the infidels should be done away and peace and union reign’.191

Modern historians192 suggest that since the Templars had just received a substantial donation from Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony, they would not have defied the King for a mere 2,000 besants. More probably, living in proximity to the Assassins, they thought that Amalric was being hood-winked. Nor were they alone in their mistrust of the Assassins: after Amalric’s death, Raymond III, Count of Tripoli, whose father had been killed by the Assassins, was made regent of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Negotiations with Sinan were not reopened, and there was no further talk of his conversion to the faith of Christ.