I got the Simpsons job the same way I got a wife: I was not the first choice, but I was available.

I was working at It’s Garry Shandling’s Show, the second-lowest-rated show on TV. (The lowest-rated was The Tracey Ullman Show, which featured short cartoons about these ugly little yellow people.) The Shandling show was going on summer break and showrunner Alan Zweibel was launching a new show, The Boys, a sitcom set at the Friars Club. Man, I wanted that job, where I would have been writing jokes for Norm Crosby and Norman Fell, two of my favorite Normans!

But Zweibel opted to hire my old friends Max Pross and Tom Gammill, so my writing partner, Al Jean, and I had to settle for the job they turned down: The Simpsons.

Nobody wanted to work on The Simpsons. There hadn’t been a cartoon in prime time since The Flintstones, a generation before. Worse yet, the show would be on the Fox network, a new enterprise that no one was even sure would last.

I took the job . . . but didn’t tell anyone what I was doing. After eight years writing for films, sitcoms, and even Johnny Carson, I was now working on a cartoon. I was twenty-eight years old and I thought I’d hit rock bottom.

Still, I’d been a fan of Matt Groening and executive producer Sam Simon for years. They were having fun creating the show, and it was infectious. It was a summer job and it felt like the summer jobs I’d had in the past (selling housewares, filing death certificates): we knew we wouldn’t be doing this forever, so no one took it too seriously. We didn’t even have a real office at the time. The studio had so little faith in us, they housed us in a trailer. I assumed that if the show failed, they’d slowly back the trailer up to the Pacific and drown the writers like rats.

Al Jean and I quickly churned out three of the first eight episodes of the show: “There’s No Disgrace Like Home,” which ends with the Simpsons electrocuting each other during family therapy; “Moaning Lisa,” in which a depressed Lisa meets jazz great Bleeding Gums Murphy; and “The Telltale Head,” where Bart saws the head off the Jebediah Springfield statue. This is also the episode in which Sideshow Bob, Reverend Lovejoy, Krusty the Clown, and bullies Jimbo, Dolph, and Kearney first appear.

But the whole time I was writing, I groused, “I’d rather be doing jokes for Norman Fell.” Since so few writers wanted to work on the series, we wound up with a very eclectic writing staff: except for Al and me, none of them had ever written a sitcom script before. They’d come from the world of sketches, late-night TV, even advertising. One day before the series premiered, I was sitting in the trailer with the other writers. After Matt Groening left the room, I asked the question that was on all our minds: “How long do you actually think this show will last?”

Every writer had the same answer. Six weeks. Six weeks, six weeks, six weeks. Only Sam Simon was optimistic. “I think it will last thirteen weeks,” he said. “But don’t worry. No one will ever see it. It won’t hurt your career.”

Maybe that’s the secret of the show’s success: since we thought no one would be watching, we didn’t make the kind of show we saw on TV; we made the kind of show we wanted to see on TV. It was unpredictable; one week we wrote a whodunit, and in another we parodied the French film Manon of the Spring. The only rule was one we made for ourselves—don’t be boring. The scenes were snappy and packed with jokes, in the dialogue, in the foreground, and in the background. When Homer went to a video arcade in episode 6, Al and I filled the place with funny games like Pac-Rat, Escape from Grandma’s House, and Robert Goulet Destroyer. And if you missed a joke the first time, no problem; everyone in America was starting to get VCRs, so they could tape the show and watch it again.

Remember, this was 1988, and the number one TV series was The Cosby Show. It was a great show . . . but it was slooooow. Nothing ever happened on The Cosby Show. (A lot happened after The Cosby Show . . .)

It’s no joke to say that the fastest-paced, most irreverent comedy on TV around this time was The Golden Girls, a show about three corpses and a mummy. (I broke into sitcoms writing a script for The Golden Girls. Now I am one.)

DAN CASTELLANETA ON THE SIMPSONS’ PROSPECTS

“When I read the first script, I was blown away. I really thought it was well written. I didn’t know whether or not the show would be successful, but if we only had thirteen episodes, we would at least have a cult following. The scripts were that good.”

Sam Simon taught me everything I know. About boxing.

The Simpsons Speak

After a year spent preparing thirteen scripts, it was time for a table read. This is when the writers and producers get together in a conference room to hear the actors perform the script for the first time. It’s probably the most important part of the process. How do the characters sound and interact? Does the story flow? Do the jokes get laughs from the fifty or sixty people in the room?

Our first table read was in early 1989—it was the first time the Simpsons cast was gathered in one place, the first time they acted out a full episode of the show. I recognized Dan Castellaneta (Homer) from The Tracey Ullman Show; as for Julie Kavner (Marge), I’d had a crush on her since she played Brenda Morgenstern on Rhoda. Still do. Even though I’d cowritten three episodes by this point, I had no idea the children’s voices were done by adult women. I’d assumed Bart was played by a young boy, not thirty-two-year-old Nancy Cartwright; it was even weirder that Yeardley Smith, a grown woman, barely changed her voice to play Lisa Simpson.

Oh, that poor girl, going through life stuck with that voice, I thought. That “poor girl” has since earned an Emmy and $65 million with that voice.

Hank Azaria hadn’t been cast yet; at that time, his character Moe was played by comedian Christopher Collins. (When Hank was later hired, he went back and re-recorded all of Moe’s lines). Cartoon legend June Foray (Rocky the Flying Squirrel!) also did a few parts at that first reading, but she sounded too cartoony for our show. A local radio personality played psychiatrist Dr. Marvin Monroe, but he was fired at the end of the reading. (We later killed off the character of Marvin Monroe. And the real radio shrink we based him on committed suicide. All in all, kind of a cursed character.)

Comedy writer Jerry Belson, considered one of the funniest men in the world, was brought in to punch up the script with new jokes. He offered only one: a psychiatric patient we described as “Nail-biter (not his own)” was changed by Jerry to “Bedwetter (not his own).”

I didn’t realize what a momentous occasion this table read was because, frankly, it wasn’t. The whole thing played a little flat. Kind of slow. A few laughs. No one would ever have guessed from that first table read that we’d be doing six hundred more of them. The prospects for The Simpsons weren’t great, and they were about to get even bleaker . . .

We Almost Get Canceled . . . Before We Come On

Fox had to take a giant leap of faith when the network picked up The Simpsons for the first season. With an animated show, a studio can’t just do a pilot and then decide later to pick up the rest of the series. It’s prohibitively expensive to make only one episode of a cartoon. Animation is also a slow process: there would be a one-year gap between the pilot and the first episode. By that time, half the network executives who’d bought the show would have been fired, forced out of the business, and possibly become fugitives from justice.

So Fox had to pick up a whole season of The Simpsons and paid something like $13 million for thirteen episodes without seeing one frame of animation.

Our first finished, full-color episode, the pilot, “Some Enchanted Evening,” had just come in from overseas. While our basic creative animation is done in Hollywood, the actual drawing and hand-painting of over twenty-four thousand cels in each episode is done in Korea. South Korea. The nice Korea. The plot of the pilot has the notorious Babysitter Bandit trying to rob the Simpsons’ house while Homer and Marge are having a romantic night away from the kids.

When the writers and Fox executives got together and watched it, they thought it was terrible. A total disaster. The script was clumsy—pilots often are—but it was the animation that felt completely wrong: the Simpson house was bendy, Homer was wiggly, all of Springfield seemed to be made of rubber.

When the screening ended there was dead silence. The small audience in attendance gaped at the screen like it was the first act of Springtime for Hitler. Someone had to break the silence. Finally, writer Wally Wolodarsky shouted with ironic glee, “Show it again!”

Fox was up in arms. It’s possible this would have been the end of The Simpsons. But the next week, a second episode, “Bart the Genius,” came in, where Bart cheats on an IQ test and ends up getting sent to a school for gifted children—and that episode, thankfully, was just great. It was directed with a sure hand by David Silverman, and the script was by one of our best writers, Jon Vitti. It reaffirmed everybody’s faith in the series.

This forced us into switching around the original order of how the episodes were to be aired. And so The Simpsons premiered, three months late, with episode 9, “Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire,” as a Christmas special. “Bart the Genius” would be the first regular episode; and the original pilot became our season finale, giving us time to fix the animation.

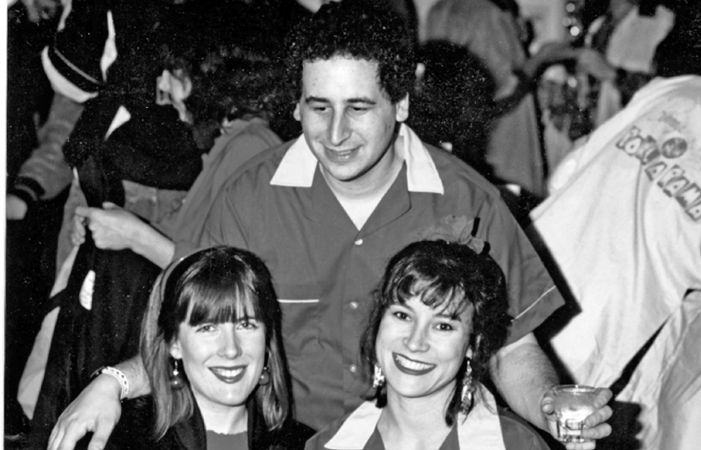

In December 1989, we had a premiere party for the Christmas show in a bowling alley. It was pretty low-rent as premiere parties go, but then Fox wasn’t eager to throw more money at our expensive little series.

And then, at eight P.M., the show aired. We all stopped bowling to watch it on overhead monitors. And . . . it was funny, touching, smart, and sweet; none of us saw it coming.

Soon after, someone from Fox’s publicity team came in with a packet of reviews from newspapers across the country: the critics not only loved the show, they recognized it as “ground-breaking,” and a “game-changer.” The next morning, we learned that The Simpsons had debuted to the highest rating in the history of the Fox network. We were a success right out of the gate, and we were all over the moon. Except for one man.

Sam Simon stood at the back of the bowling alley, flipping through the packet of reviews with a wry smile on his face. At last, he said with a rueful laugh, “They don’t mention me once.”

It’s not as petty as it may sound. The Simpsons was the greatest thing Sam had done in an already great career that included Taxi and Cheers. Sam had hired all the Simpsons writers, set the tone of the show, worked out all the stories, and supervised every script . . . and, to his surprise, Matt Groening got all the acclaim.

Matt never hogged the credit. Whenever he did an interview, he would mention all of us by name. When he went on The Tonight Show, I remember, he kept bringing up the other writers . . . but Jay Leno cut him off.

Why?

The Simpsons’ premiere party, at a bowling alley, in 1989. Me; my wife, Denise; and Sam Simon’s first wife, actress Jennifer Tilly. This was the night everything fell apart.

It made for a great story: “TV is being changed by this underground cartoonist who’s breaking all the rules. . .” instead of “TV’s been changed by an underground cartoonist . . . and a veteran TV producer (Sam Simon).”

And so The Simpsons was launched. The public loved us. The critics loved us. And the creators were beginning to hate each other.

Simpsonsmania!

Months after our premiere, The Simpsons was not just in the papers every day; it was in every section of the newspaper! News, Entertainment, Sports, Business: editors realized a cartoon of Bart was more eye-catching than, say, a photo of Secretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger. And 90 percent of what I read about The Simpsons was wrong, which made me realize 90 percent of everything I read in the paper was probably wrong.

Example: When blues guitarist Stevie Ray Vaughan died in a helicopter crash, one newspaper reported that his last act had been to record a song for the upcoming The Simpsons Sing the Blues album. In truth, Mr. Vaughn’s last act was to say something like “Fuck The Simpsons! I’m not recording a song for their stupid album.”

In 1990, Matt Groening wound up on a list as one of the ten most admired men in America, while Sam Simon was the answer to a trivia question on a Simpsons bubble gum card. The world kept forcing all the credit on Matt, and it made Sam miserable. He could be a wraith in the office, stomping around like Salieri in Amadeus.

Sam was still running the show and turning out classic scripts; he could be great fun to be around. But when Matt came into the room Sam would glower at him and make nasty asides till Matt walked out.

I sympathized with Sam, but I felt bad for Matt, too. Here was the crowning achievement of his life . . . and he was unwelcome in his own office. One day, I went to Matt privately and told him, “Not everybody hates you.”

When Matt told Sam a writer had said that, Sam got furious: You’re lying! Who was it? I never fessed up and I never will.

Oh crap! I just did.

Amazingly, Sam turned his bitterness into a great episode. He pitched a story where Homer, like Sam, creates something truly extraordinary . . . and Moe gets all the credit for it. Homer becomes twisted with rage and destroys them both. The show is called “Flaming Moe’s” and is considered one of the best Simpsons episodes ever.

This cold war went all the way through the first two seasons. By the end, Sam and Matt were not talking, casting a pall over what should have been happy, glorious years. So how was it resolved? They told Sam to stop running the show, and put two saps in charge: me and Al Jean. Up until that point, the biggest thing I’d ever run was a dishwasher.

AL JEAN ON TAKING OVER THE SIMPSONS

“Mike and I were so intimidated because we knew this was a great show, a classic. We had left ALF after season 2, and by season 4 it was already off the air. So I was really scared that if The Simpsons was canceled while we were running it, we’d be blamed for ruining this incredible thing. And there was a history of shows that appeal mostly to kid audiences, like Mork & Mindy or ALF, that shoot up and then shoot back down very quickly. They become evanescent. So Mike and I worked on The Simpsons nonstop to make sure that didn’t happen to us.”

Who’s the Genius?

Decades after the Matt and Sam conflicts, fans still ask: who’s the one genius responsible for The Simpsons? It’s a show with twenty writers, dozens of animators, forty-seven producers, and ten regular or semiregular voice actors, but everyone wants to find the one guy responsible. It’s understandable—everyone loves a hero story.

For years, the title went to Matt Groening. He did, after all, create the little buggers. Then the honor shifted to Sam Simon, and then to writer George Meyer, after he was written up in The New Yorker, that gut-bustingly funny magazine. Strangely, no one has ever given the credit to me . . . including me.

Who’s the genius? My answer to the question narrows it down to three people. Actually four. No, five. Make that thirteen.

Matt Groening definitely created the Simpsons, and the story of how he did it is truly unbelievable. Matt was a Los Angeles underground cartoonist when he was called in for a meeting at The Tracey Ullman Show. The series had one-minute animated bumpers (as well as live novelty acts), but no one was particularly enamored with them. Matt was told this was a “get-acquainted meeting”—he wasn’t expected to pitch anything. But shortly before the meeting, someone said to him, “We’re very excited to hear about your new project!” Matt didn’t have one. And so, five minutes before the meeting, he sketched out the Simpson family.

It took him five minutes to create one of the most-honored shows in TV history. Just imagine if he’d spent half an hour.

How did he come up with it so fast? For starters, he named the characters after his family: his parents, Homer and Marge; his sisters Lisa and Maggie. He claims Bart is just an anagram of brat, but I think the name may have been inspired by his brother, Mark.

The Simpsons shorts are crudely made—so crude, in fact, that they’ve never been released on DVD; so crude that even Fox has never tried to make a buck on them. But they quickly evolved, thanks to Matt’s graphic genius. He once told me, “The key to the Simpsons is that each character is recognizable in silhouette.” It’s an amazing insight, one I never heard from any other cartoonist. In the earliest days of the show, when we’d be screening rough animation, he’d stop tape every few seconds: “I hate those lines around Bart’s eyes! That napkin holder is too small!” I thought he was nuts, but watching those old shows now, I see that he was creating the precise look of the show as he went along. Also, the napkin holder was too small.

When the call came to turn the shorts into a half-hour series, Matt was paired with Sam Simon. Sam was a TV prodigy, having run the show Taxi at age twenty-three, before moving on to Cheers and It’s Garry Shandling’s Show. Sam supervised the writing of The Simpsons’ first two seasons and developed the show’s signature mix of highbrow and low, all moving at warp speed.

So if Matt is Thomas Edison inventing the lightbulb, Sam is George Westinghouse, building the factory to crank the bulbs out.

Then there’s James L. Brooks. (I call him Jim—you don’t get to.) Jim gave the characters soul and pitched the long, heartfelt monologues that gave the Simpsons unexpected depth. To continue the metaphor, Jim Brooks gave the lightbulb heart. Okay, let’s drop the metaphor.

There’s a simple mnemonic to remember it all: Matt did the art; Sam made it smart; Jim gave it heart. Easy, but wrong, because Matt and Jim also pitch great jokes, and Sam was no slouch at art. He was a college cartoonist who went on to design Mr. Burns and Bleeding Gums Murphy.

Speaking of art, let’s not forget David Silverman, the animation supervisor of the show for decades. He first pitched the idea to Jim of turning the one-minute Simpsons shorts into a half-hour show. David had to reinvent how to produce a weekly animated series—it had been twenty years since The Flintstones was in prime time, and no one remembered how it was done. Silverman refined the style of the show and set a high standard for the animation. (Even as a kid watching The Flintstones I thought, “They keep running past the same goddamn palm tree!”) David had brilliant animators working under him, including future Oscar winners Brad Bird (Ratatouille, The Incredibles) and Rich Moore (Zootopia).

And we can’t ignore Al Jean, who has had the soul-crushing job of showrunner on The Simpsons for twenty of its thirty seasons. Nor can you forget our six main cast members—Dan Castellaneta, Julie Kavner, Nancy Cartwright, Yeardley Smith, Hank Azaria, and Harry Shearer—who created the voices of not only the Simpson family but the other two hundred residents of Springfield as well.

That’s the answer—those thirteen men and women are the one guy who is most responsible for The Simpsons.

That’s All, Folks!

In 1993, midway through season 4, Sam Simon was asked to leave the show he helped create; in 2015, he passed away at the young age of fifty-nine. He retained his executive producer credit (and salary) on The Simpsons through the end of his life, although he hadn’t worked on the show, or even set foot in the office, for more than two decades. As for Matt, Futurama later proved that even without Sam’s help he could create a smart, visionary show.

In the end, Sam got over his anger, saying, “I’ve gone from getting too little credit for The Simpsons to too much.” Matt said something similar to LA Weekly in 2007: “I’m one of those people who gets more credit than I deserve.”

There you have it: the one dark secret of our show, the lone bruise on the Simpsons banana. That’s all the gossip I’ve got. (Okay, there’s a little bit more ugliness in chapter 12, during the Simpsons/Critic crossover.)

Maybe that’s the key to the show’s longevity—there’s no drama at our comedy show. The Simpsons keeps rolling along because everyone gets along: the cast, the animators, and the writers all respect each other. There are still plenty of stories and secrets to tell about the show, but if you want dirt, dig a hole.

Now, let’s step back a little to how I got here . . .