I spent the first eight years of my career writing for real live people (if you count ALF and Joan Rivers). However, “once you go toon, you won’t be back soon,” as no one ever said. It is very liberating to write for cartoon characters because they don’t take the jokes personally. Marge’s sister can say, “Am I wrong, or did it just get fatter in here?” and Dan Castellaneta’s feelings are not hurt. Cruel lines fly freely on The Simpsons and our actors never take it to heart.

Only once did a Simpsons actor resist a line. Hank Azaria didn’t want to record Moe’s response to a prank phone caller: “I’m a stupid moron with an ugly face and a big butt and my butt smells and . . . I like to kiss my own butt.” But eventually he did it!

Contrast this with Roseanne, a great TV series about an elephant married to a hippopotamus. For nine seasons, Roseanne insulted everyone in sight, but nobody ever responded, “Shut up, fatso.” No one ever seemed to notice her weight. Why? Because Roseanne was a human being. And it was her show.

So, it was with some trepidation that I went back to the world of writing for human beings. The results were . . . mixed.

Jokes for Bob Hope? Nope, the Pope!

I wrote jokes for Johnny Carson, the Pope of late-night TV. But I also wrote gags for Pope Francis, the Johnny Carson of the Catholic Church. It started with my friend Ed Conlon, who’s from a big Irish family: his aunts are all nuns, his uncles are priests; his mother’s a nun; his father is also a nun. I was at his St. Patrick’s Day party when I met Father Andrew, the Friar Tuck–ish head of Catholic charities for New York. “You wanna see the Pope’s app?” he asked. At least, I think he said “app.”

It was called Joke with the Pope, and had videos of celebrities and nobodies telling jokes to Pope Francis. Through some mechanism I’ve never understood, this would benefit orphans in Cambodia and Venezuela. I could just picture the poor waifs saying, “I sure liked that joke George Lopez told the Pope, but I’d still rather have parents. Or pants.”

Father Andrew emailed me at midnight, later that week: “We need a joke for Al Roker to tell the Pope. It needs to be about religion and weather and it must be clean.” I came up with this: “The California drought is so bad people in Napa are asking the Pope to change the wine into water.”

No one thinks that joke is funny—they always say it’s “cute.” CUTE, I realized, is an acronym for Completely Unable To Entertain. But the joke made it to the app, so every few nights, Father Andrew would email me, requesting jokes for Mayor Bloomberg, Conan O’Brien, David Copperfield, and on and on. There are eight hundred million Catholics on earth, but somehow the church had to bother me. I was a Jew writing jokes for the Pope. For free. That’s two sins. Still, Jesus relied on Jewish writers for his Gospels, too.

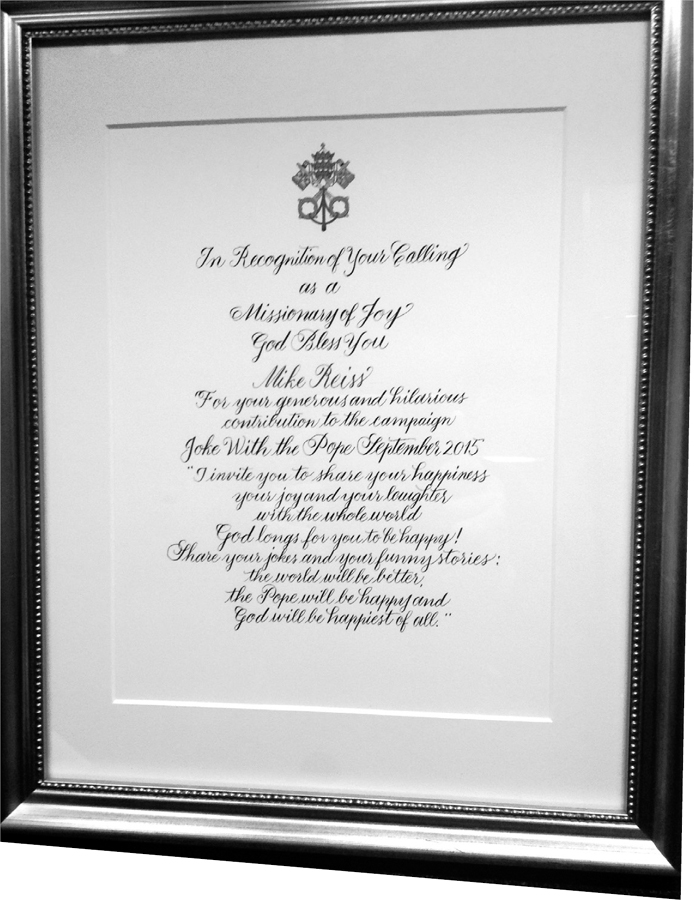

When the project finally wrapped, the charity threw itself a very lavish party. And, to my complete surprise, I was presented with a plaque from Pope Francis, naming me “a Missionary of Joy.”

“Well,” I quipped to the clergymen assembled, “this isn’t the first time a priest has put a man in the missionary position.”

Next time, they should pay me.

See? I really did win an award from Pope Francis. I wouldn’t have believed it, either.

A Half-Life in the Theater

After thirty-five years of working movies and TV, I started writing plays. Why? Because after a while you get tired of earning money and having people see your work.

I fell into theater by accident. My wife and I were in London, and we saw a playhouse showing Waiting for Godot starring Ian McKellen and Michael Gambon (that’s Gandalf and Dumbledore to you). The show was sold out, but we decided to stand on the ticket line, hoping for someone to cancel their tickets. We waited for two hours but never got in. “Couldn’t this be a play?” I asked my wife. “Waiting for ‘Waiting for Godot’?”

My wife said, “No,” but I wrote it anyhow. I even got my friend’s sister, a theater director, to stage the show. The one-act play opens as Dave arrives at a theater showing Waiting for Godot and it’s sold out. He calls his wife as another man listens:

“Honey, I couldn’t get tickets. Is there another show you want to see? What’s that? ‘Go fuck yourself’? It sounded like you said . . . Go Fuck Yourself.” Dave explains to the other man: “That’s the new David Mamet play.”

The opening line got an enormous laugh, much better than it deserved—and I was hooked. Theater was easy, the audiences were generous, and the actors did every line I wrote. I learned this during my first full-length play, I’m Connecticut, which won every award you can win. In Connecticut. The play featured a tough-talking Massachusetts guy: “In Boston, we call a milkshake a frappe. A frappe. What is that? It’s ‘crap’ with a ‘fff’.’ And we call ice cream sprinkles jimmies. Who the hell is Jimmy?”

Every night, the actor would end that speech, “Who’s the hell is Jimmy?” I liked it—it didn’t make much sense, but it was good character.

When the play finally closed, I checked the script—it was a typo. In theater, the actors do your typos.

My Rep in Ruins

After visiting half the countries on earth, I was able to put my world travel to good use: in 2009, I wrote a sweet little romantic comedy film called My Life in Ruins. It was about a bus tour of Greece, and had big laughs, gorgeous scenery, and a simple message: don’t judge others too harshly.

One critic called it “execrable.”

I was fully prepared for bad reviews, but nothing quite this vicious. Sledge Hammer! star David Rasche, who’d been in a critically trashed play, tried to spin it: “‘Execrable’ can mean ‘deserving to be excreted.’ See? ‘Deserving.’ That’s good! Or it can mean ‘of poorest quality.’ Okay, see? ‘Quality.’ That is also very good!”

I was surprised because my film was the highest-testing movie in Fox Searchlight history. Audiences liked it more than, say, Little Miss Sunshine and Slumdog Millionaire. But not the critics. They called it “one big fat Greek disaster”; “wretched”; “thuddingly bad”; “a film that will kill Greek tourism”; and “a steaming pile of stereotypes and sitcomery, a pathetic excuse for a comedy.” That last review sent my wife to a sickbed for three days, with what Victorian doctors used to call “the vapors.”

Roger Ebert, who’d guest-starred on my show The Critic, called me an imbecile. Other critics singled me out, calling me “an idiot” and “sub-literate.” Now, I opened the film with an allusion to Voltaire—a sign reads PANGLOSS TOURS: “THE BEST OF ALL POSSIBLE WORLDS.” In Candide, Dr. Pangloss utters these optimistic words before his group sets out on an utterly disastrous journey. Just like the tourists in my film! Get it? The critics didn’t. Not one caught the allusion. Otherwise, they’d have called me a “sub-literate moron who reads Voltaire.”

We all have to deal with criticism in this world. But only people in entertainment have to deal with critics. You may get a performance review at work that reads, “Jim’s efficiency in processing claims is down 11 percent; needs improvement.” If it read, “Jim’s work recalls a drooling monkey who can’t tell a banana from a ballpoint pen”—well, you’d have grounds for a lawsuit.

I can’t speak for all writers, but for me, bad reviews hurt. I can still quote you every nasty write-up I’ve gotten over the past thirty-five years. Why shouldn’t I? I try my best on everything I do, and my works are my babies. I don’t want Manohla Dargis coming to my home and saying, “Mike Reiss’s newest offering, Mike Jr., is a babbling, bloated sequel to the thoroughly unpleasant original. Avoid this soggy diaper of a child.”

My movie was panned and my book was banned. I needed to retreat to a safe space. It was time to head back to The Simpsons.