Four Episodes That Changed the World (Kinda)

If you Google “Simpsons Best Episode List,” you’ll get 20,100,000 hits. If you Google “Simpsons Worst Episode List,” you’ll get 669,000 more (yeesh!). The point is, the world doesn’t need another list of best episodes. Instead, I’d like to tell the never-before-told stories behind four Simpsons episodes I worked on that broke new ground and changed the series forever.

Seminal Episode Number 1: “Like Father Like Clown”

Often it takes just one joke to clinch an idea. This was the case with Jay Kogen and Wally Wolodarsky’s “Like Father, Like Clown.” It was a take on The Jazz Singer, with Krusty the Clown estranged from his Orthodox rabbi father. The problem was we’d never even said Krusty was Jewish in the show before. But then Al Jean pitched, “His real name should be Krustofsky.” It got a big laugh, particularly from Jim Brooks, and the idea was approved.

The show established a number of precedents:

- IT WAS ABOUT A PERIPHERAL CHARACTER. Bart and Lisa save the day here, but it’s Krusty’s story, going all the way back to his childhood. Since then, we’ve explored almost every character’s backstory, from Sideshow Mel’s acting career to Carl’s Icelandic roots. “Like Father, Like Clown” was a big revelation: The Simpsons doesn’t have to be about the Simpsons.

- OTHER RELIGIONS ARE FUNNY, TOO. This was only episode 41, but we’d already explored the family’s religion, a Protestant sect called Presbylutheranism. But this show explored Judaism in a big way; in years to come, we’d tackle Homer’s conversion to Catholicism, Apu’s Hindu faith, and Lisa’s embrace of Buddhism. We’ve made fun of every religion except Islam. There’s nothing funny about those guys. Don’t hurt us!

- HOMEWORK PAYS OFF. The episode ends with a Talmudic debate between Rabbi Krustofsky and Bart. To write this, we enlisted the help of three real rabbis, as consultants. It remains the most scholarly debate you’ll ever see on the nature of comedy and Judaism. In a cartoon. On Fox. Jay and Wally wrote a terrific script; it was beautifully animated by Brad Bird. And Jackie Mason, a former rabbi himself, was unexpectedly moving as Rabbi Krustofsky—he won an Emmy for the role.

We also learned another lesson—if you want to make a touching TV show, rip off a touching movie. The Jazz Singer has been remade several times—starring, respectively, Al Jolson, Danny Thomas, Jerry Lewis, and Neil Diamond. (It gets worse and worse!) It has always been a lousy movie, and yet the ending—where the rabbi reconciles with his entertainer son—always works.

It worked for us, too. The day after it aired, editorials praised the show. The Fox switchboard was flooded with calls: one man said it moved him to contact his father for the first time in twenty-five years. It was then that we realized our fans truly cared about our characters—all of our characters.

Except Lenny.

Seminal Episode Number 2: “Homer at the Bat”

“Homer at the Bat” changed the tone, the casting, the very reality of the show. It also saved a young boy’s life. Really! What more could you ask for? Homer getting into the National Baseball Hall of Fame? Yeah, that happened, too.

It began when Sam Simon called Al Jean and me into his office to pitch a new story. Sam would explain an episode the way Oliver Hardy would lay out a scheme to Stan Laurel—in tiny, singsongy chunks, with long pauses in between. “Mr. Burns . . . is going to have . . . a softball team! And he’ll hire nine ringers . . . to play on it! And we’ll get nine professional ballplayers . . . to play themselves!”

This was season 3 of the show, and the previous seventeen episodes had covered baseball, mini golf, boxing, soapbox racing, and football. Now we were doing baseball again. As might be expected from a show written primarily by single men, The Simpsons was sports mad. For three months of every year, our office became a football pool that occasionally put out a TV show.

We even had our own bookie.

Everyone on staff loved sports . . . except me. But I served a purpose—I represented everyone’s wives and mothers in the audience. I’d be the lone voice saying, “Will everyone get this joke about Mordecai ‘Three Finger’ Brown?” Yes, I was the Staff Girl. (To this day, I don’t understand the ending of this episode—Homer wins the big game by getting knocked out cold by a pitch. How? Why? Huh? So what?)

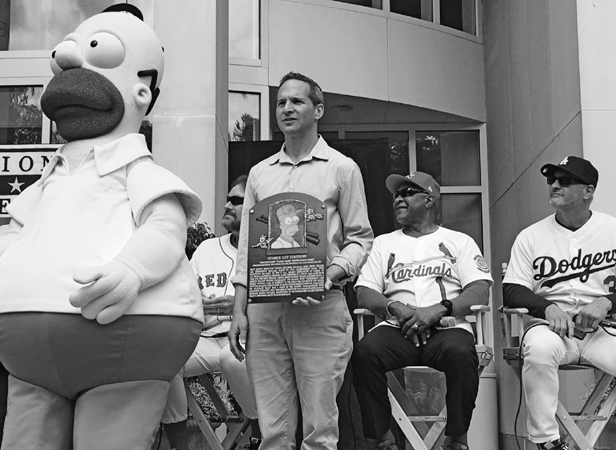

Homer is inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Seated behind are Wade Boggs, Ozzie Smith, and Steve Sax from “Homer at the Bat.”

Virtually any other Simpsons writer could have done this script. Jeff Martin and Jon Vitti had both worked as sportswriters. Al Jean would be the first person every year to buy the latest Bill James Baseball Abstract; by the following day, he had read and memorized the thousand-page doorstop.

But John Swartzwelder was our biggest baseball fan. He owns a huge amount of sports memorabilia, including what he claims is “the first baseball,” which I imagine is made of mastodon hide and autographed by Ruth—not Babe, but the babe from the Old Testament.

We cast nine real-life baseball players (only Rickey Henderson and Ryne Sandberg turned us down), and Swartzwelder created quick, crazy stories for each of them:

- Ozzie Smith visits the Springfield Mystery Spot and plunges into a bottomless pit.

- Roger Clemens gets hypnotized and thinks he’s a chicken.

- Wade Boggs gets into a fistfight over who was a better British prime minister, Lord Palmerston or Pitt the Elder.

- Ken Griffey Jr. overdoses on nerve tonic and gets gigantism. (Is that even a thing?)

- José Canseco does something nice for someone. (This one really stretched credibility.)

Up to this point, The Simpsons had been praised for its authenticity: “They’re realer than most real families on TV,” opined many a blowhard. But this episode didn’t just stretch reality, it snapped it, hacked it to pieces, and left it to die in a drainage ditch. It was a very different Simpsons episode, including the fact that the Simpsons are barely in it. Here, the guest stars were running the asylum.

Needless to say, our cast didn’t like the show. Our table reading of the script bombed utterly. Two of our actors complained about the script, the only time this has ever happened.

The baseball players were much easier to deal with. Don Mattingly had the only gripe: his character makes his first appearance wearing an apron and washing dishes. “Do I have to do this?” he moaned.

“I’m sorry, it’s in the script, it can’t be changed,” Al Jean lied.

“Okay,” Mattingly grumbled.

The players were surprisingly good actors. Mike Scioscia could be a real professional; in voice acting, you never know who’s going to have the gift. (When Aerosmith did our show, their bass player Tom Hamilton had great comic timing and a huge range of funny voices.)

And then there was Ken Griffey Jr. He got angry because he didn’t understand his line “There’s a party in my mouth and everyone’s invited.” (If he had understood it, he’d have been really angry.) Adding to the pressure, his father, Ken Griffey Sr., was there trying to coach him through the line, and it wasn’t helping.

The room was going to implode, so that’s when they called in me, the Staff Girl. Since I didn’t really know who Griffey was, they figured I wouldn’t be intimidated by him. Al shoved me into the tiny recording booth. This instantly became my new worst fear: to be locked in a small glass booth with a large angry man; and I couldn’t get out until I made him say a vaguely homoerotic line.

It took a few takes, but we got the line. Decades later, Griffey appeared in a mockumentary about the episode—he’s become a much better actor.

Despite the misgivings of the cast, “Homer at the Bat” was a huge hit. It was the first time we beat our competition, The Cosby Show. We beat Cosby several more times after that; within two years his show was off the air.

It’s also the show that intoxicated us with guest stars, and helped us realize we could get almost anyone we wanted. The next year, I insisted we do an all-star spectacular with celebrities I’d heard of: it was “Krusty Gets Kancelled,” and it featured Elizabeth Taylor, Johnny Carson, Bette Midler, and many more. (Many more, but not Mandy Moore—I’m not a fan.)

“Homer at the Bat” also stretched the reality of the show, and nobody minded. The series would get a little crazier after that—the next year we’d have Leonard Nimoy beam out of a scene like Mr. Spock. There was no turning back.

A quarter century has passed since “Homer at the Bat” debuted. Our bookie is long dead. We talk much less about sports and much more about tuition costs. Since 1992, our Staff Girl has been a real girl—currently, the brilliant Carolyn Omine.

But the episode is still remembered fondly. In May 2017, Homer was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Wade Boggs, Steve Sax, and Ozzie Smith showed up at the ceremony. Smith said the number one question he gets asked is “How did you escape the Springfield Mystery Spot?” Boggs said he still sticks up for Pitt the Elder.

Oh yeah, and before I forget, the show really did save a kid’s life. The episode opens with Homer choking on a doughnut; his friends ignore a prominently placed poster showing the Heimlich maneuver to study the sign-up sheet for Burns’s softball team. A week later, the Los Angeles news featured an eight-year-old boy who saved his friend who was choking to death. When asked where he learned the Heimlich, he said, “It was on a poster on The Simpsons.” True story.

And the name of the boy whose life was saved? It was Ryan Gosling.

That part’s fake. I just needed an ending.

Seminal Episode Number 3: “Moaning Lisa”

In the first season, we were excited when our hero Jim Brooks wanted to pitch us an episode. His idea? Lisa is sad. That’s it.

Jim would work out the details with us: Lisa is depressed and Marge can’t help her. Then Lisa finds a jazz mentor in Bleeding Gums Murphy, who teaches her it’s okay to be sad—and that cheers her up.

It didn’t sound like a lot of fun, and it certainly didn’t seem like a great use of animation. No one had much faith in the idea at the time. “Oh, you got stuck writing that one,” Matt Groening said with a smirk.

“Jim’s been trying to do this story since Taxi,” Sam Simon told us. “Nobody would let him.”

Jim’s instinct was right, however, because this was the episode that cemented Lisa as a character. Up until then, she’d just been kind of a girl Bart. The first line we ever wrote for her was something she’d never say now: “Let’s go throw rocks at the swans.”

“Moaning Lisa” is the episode that first showed viewers the deep emotional reserves in The Simpsons, that a cartoon had the ability to move you, and even bum you out. Most of all, it showed that we weren’t just a show for boys.

Since then, jazz has become a major element in our show. Not that any of us really like jazz.

I have always proudly thought, There’s never been a sitcom episode quite like “Moaning Lisa.” Then I watched a rerun of Jim Brooks’s old series The Mary Tyler Moore Show—the plot of which is “Murray is sad.” The episode even ends with Mary giving pretty much the same inspiring speech that Marge gives Lisa. But as Judd Apatow points out, “To me, a great Simpsons episode should feel like a great Mary Tyler Moore. There are some silly episodes, too, but I love the ones about people finding ways to connect with something larger. And The Simpsons has done this so many times in so many ways.”

Six years later, Al and I pitched the sequel episode where Bleeding Gums dies. Ron Taylor, the lovable voice of Murphy (he looked exactly like the character) was at the cast reading of the script, and when we got to the point where he passes away, Ron shouted, “I’m dead?” He’d flown in from Colorado for the reading without ever looking at the script.

AL JEAN ON “MOANING LISA”

“People always tried to put labels on Mike and me. As a team, we were known as ‘joke guys’ on The Tonight Show or goofy shows like ALF. But when we got to The Simpsons, we wanted to do more emotional stories, like stories about Lisa, because we wanted to show we could do those kinds of things, too.”

Seminal Episode Number 4: “Treehouse of Horror” (The First One)

The Simpsons’ first season was a cultural phenomenon. Now, two episodes into the second season, we were doing a Halloween show, a trilogy of terror. It was a tremendously risky move. Just minutes into the show, we see a zombified Lisa, carrying a knife, about to murder her whole family. Maggie’s head rotates like a lawn sprinkler.

It was so frightening that we opened the show with a disclaimer: Marge comes out from behind a stage curtain (aping an actual filmed preamble to the original Frankenstein) and warns the audience, “Tonight’s show, which I totally wash my hands of, is really scary. So if you have sensitive children, maybe you should tuck them in early tonight, instead of writing us angry letters tomorrow.”

The warning proved unnecessary: our fans loved the show. We did, too—how often do frustrated writers get to kill off their characters? A tradition was born.

The shows got bloodier and creepier every year, and no one complained. Nobody even cared when we showed it; if it aired anytime between September 12 and November 15, it was a Halloween show.

The show gets harder to write each year; by this point, we’ve had to come up with eighty-seven different horror archetypes. We quickly spoofed every horror film classic and all the great Twilight Zones. Now we’re parodying thrillers (Dead Calm), great arthouse dramas (The Diving Bell and the Butterfly), lousy arthouse dramas (Eyes Wide Shut), even Dr. Seuss. Lately—and this is really scary—we’ve had to come up with original stories! Make it stop!

It’s even tougher on the animators: almost every segment has to be designed from scratch, drawing new characters, costumes, and sets. It’s the first show we produce each season, which means we start the year by blowing out the budget and burning out the animators.

Even coming up with our own Halloween names for the credits has become a chore. I’ve been Murderous Mike Reiss, Macabre Mike Reiss, Dr. Michael & Mr. Reiss, Ms. Iris Eek (an anagram), The Thing from Bristol Connecticut, and The Abominable Dr. Reiss. (Hey, Dad—I finally became a doctor!)

We also learned one thing not to do from that first Halloween show: don’t get pretentious. The third segment of that Treehouse of Horror was a retelling of “The Raven,” starring Bart and Homer. It was literate, gorgeously animated . . . and boring. Edgar Allan Poe is a literary genius—my favorite author, in fact—but nobody ever called him funny. When we saw the finished animation, we realized we had to gag it up. We pieced together odd bits of animation to make new cutaway scenes where Bart makes fun of the poem. It helped, but it’s still pretty stiff.

To this day, professors tell me how much they love that segment. Scholars cite it in academic papers. English teachers show it to their classes.

God, I’m so ashamed.

Special Mention: “Homer and Lisa Exchange Cross Words”

The Simpsons writers love puzzles. As early as our first season, we had Bart anagramming a restaurant sign, changing COD PLATTER TO COLD PET RAT.

Two decades later, we built an entire episode around puzzles, in our Da Vinci Code parody “Gone Maggie Gone”: Maggie is kidnapped (by nuns!) and Lisa must solve a series of riddles to find her. My contribution: Lisa must find “the biggest ring in Springfield.” It’s the letters R-I-N-G in the town’s giant SPRINGFIELD sign.

Crossword puzzles are our writers’ real addiction (well, that and Percocet). Many of us start our day with the New York Times crossword. Our newest addition to the staff, Megan Amram, actually constructed a puzzle for the Times. We have one writer who does nothing but solve crosswords all day long—apparently this is what we pay him for.

I used to do crosswords to get my mind off work, but nowadays you can’t do a puzzle without encountering LISA, MOE, or APU. I recently did one where the clue was “San Francisco mass transit”: the answer was BART. Thank God, I thought. The puzzle constructor could have used a Simpsons clue, but didn’t. Then I got to the final entry: “What you might say if you can’t solve this last clue.” The answer was DOH.

D’oh indeed.

Worlds collided in this great episode, “Homer and Lisa Exchange Cross Words”:

Lisa finds she has an aptitude for crossword puzzles; she enters Springfield’s crossword tournament, where Homer, unforgivably, bets against her. To atone, Homer persuades crossword constructor Merl Reagle and editor Will Shortz (playing themselves) to create a special puzzle for the New York Times; buried in the clues and solution are Homer’s heartfelt apologies to Lisa.

What makes the episode amazing is that the final puzzle Lisa solved in our Sunday-night episode was the same crossword that appeared in that morning’s New York Times. Merl Reagle, a brilliant and funny man, had slipped an elaborate Simpsons message past millions of Times readers.

It’s worth mentioning that the episode’s author, Tim Long, is the rare Simpsons writer who doesn’t give a crap about crossword puzzles. This happens a lot on our show. The Simpsons visit Israel in “The Greatest Story Ever D’ohed”—the Israeli people loved it, and the show was nominated for a Humanitas Award for its “promotion of human dignity.” The episode was written by the rare non-Jew on our staff—Kevin Curran, a product of Catholic schools, who never set foot in Israel.

If you like puzzles half as much as we do, you might like these challenges I’ve created for Will Shortz on NPR’s Weekend Edition Sunday. (Shortz always refers to me on the air as “former Simpsons writer Mike Reiss.” Former? What has he heard that I haven’t?) None of the puzzles involve The Simpsons; they’re mostly about pop culture, and there’s a few sneaky twists thrown in.*

- Think of a two-word phrase you might see on a clothing label. Add two letters to the end of the first word, and one letter to the end of the second word. The result is the name of a famous writer. Who is it?

- Name a well-known TV actress of the past. Put an R between her first and last names. Then read the result backward. The result will be an order Dr. Frankenstein might give to Igor. Who is the actress, and what is the order?

- A famous actress and a famous director share the same last name, although they are unrelated. The first name of one of these is a classic musical. The first name of the other is an anagram of a classic musical. Who are they?

- Take the first name of a famous actress. Drop a letter. Rearrange what’s left, and you’ll get a word used in a particular sport. This actress’s last name, without any changes, is where that sport is played. What actress is it?

- Take the name of a well-known actress. Her first name starts with the three-letter abbreviation for a month. Replace this with the three-letter abbreviation of a different month, and you’ll get the name of a famous poet. Who are these two people?

- Name a famous Greek person from history. Rearrange the letters of the name to get the title of a famous Italian person from history. Who are these two people?

- Name a famous actress whose last name ends in a doubled letter. Drop that doubled letter. Then insert an R somewhere inside the first name. The result will be a common two-word phrase. What is it?

- Take two words that go together to make a familiar phrase in this form: “blank and blank.” Both words are plurals, such as “bells and whistles.” Move the first letter of the second word to the start of the first word. You’ll get two new words that name forms of transportation. What are they?

- Take the two-word title of a TV series. The first word contains a famous actor’s first name in consecutive letters. The second word is a homophone for this actor’s last name. Name the series and the actor.

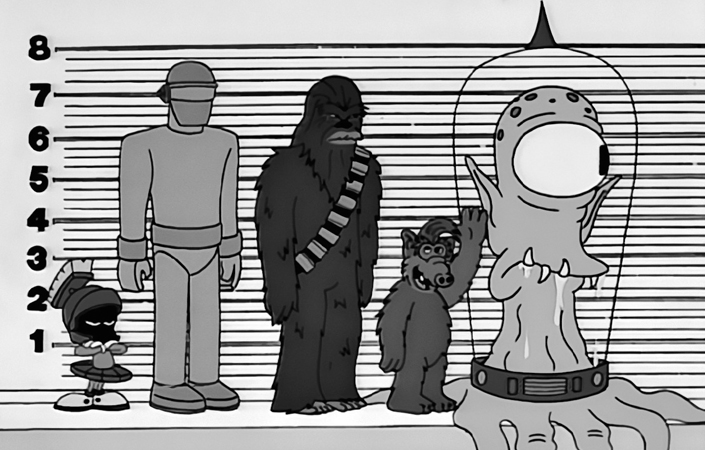

The alien lineup from our X-Files crossover show “The Springfield Files”: Marvin the Martian from Looney Tunes, Gort from The Day the Earth Stood Still, Chewbacca, ALF, and Kang (or Kodos—who can tell?). Al Jean called it “the most illegal shot in Simpsons history”: not only didn’t we get permission to use these characters, we even had Dan Castellaneta say “Yo!” as ALF. The only complaint we got was from Paul Fusco, the creator and voice of the puppet. He said, “Next time you put ALF on the show, let me do the voice!”

- Take the phrase “no sweat.” Using only these seven letters, and repeating them as often as necessary, can you make a familiar four-word phrase? It’s fifteen letters long. What is it?

- Name an occupation in nine letters. It’s an entertainer of sorts—an unusual and uncommon but well-known sort of entertainer. Drop the third letter of the name, and read the result backward. You’ll get two four-letter words that are exact opposites. What are they?

- Think of a ten-letter occupation ending in -er. The first four letters can be rearranged to spell something that a person would study, and the next four letters can be rearranged to spell something else that person would study. What is the occupation?

- What six-letter word beginning with the letter s would be the same if it started with th?

Homer’s Massive Boners

I have only a few regrets about my career, and one of them is titling this section with a boner joke. We have a pretty good sense of what our audience can handle; if you’re easily offended, you probably stopped watching back in 1990. There are only four things we’ve done in the show’s history that I wish we could do over:

- BART’S TOURETTE’S: We wrote a scene where, to get out of taking a test, Bart pretended to have Tourette syndrome. The censors had no problem with this, but thousands of viewers did; it’s the most complaints we ever got about one joke. When the show reran, we changed Bart’s ailment from Tourette syndrome to rabies, the one time we’ve ever altered a line after public outcry. Rabies is still pretty bad, but if you pet a foaming dog, it’s your fault.

- NEW ORLEANS: We did a musical parody of A Streetcar Named Desire that opened with a song making fun of New Orleans. Some of the writers were skittish, but I said, “People in New Orleans have a great sense of humor—they’re going to love it.”

Well, they don’t and they didn’t.

The song began, “New Orleans—home of pirates, drunks, and whores!” That didn’t bother them—that’s on their license plates. But the next line of the couplet was “New Orleans—tacky overpriced souvenir stores!” That’s what pissed them off.

The local Fox affiliate, owned by Quincy Jones, yanked the show off the air for two weeks. To make matters worse, Bart was supposed to be King of Carnival at Mardi Gras that year. A New Orleans reporter called to tell me, “When your friend Bart comes down here . . . we’re gonna kill him.”

I said, “Well, you know, it’s not really going to be Bart. It’ll be a tiny man in a foam rubber suit.”

The reporter replied, “Well then, we’re gonna kill him.”

They probably did.

- ADOPTING LISA: We were doing an episode where Homer’s having a triple bypass and we’d written ourselves into a corner: how does a father say goodbye to his kids, knowing he might die during surgery?

“Oh, that’s easy,” said Jim Brooks, and he pitched a scene off the top of his head: Lisa whispers to Homer all the things he needs to tell Bart; then Bart does the same for Lisa.

It was clever, funny, and exceptionally moving. Except for one line. Jim Brooks had Bart telling Lisa, “I guess this is the time to tell you . . . you’re adopted and I never liked you.”

Many parents of adopted children complained that this is their kids’ worst nightmare.

A decade later, my friend was developing a sitcom about a girl who feels she doesn’t fit in with her family. She said, “We’re calling it Maybe I’m Adopted.”

“No, you’re not,” I said. “You’ll never get away with it.”

“Oh, I will,” my friend said. “The network loves the title.”

When the show eventually came on, it was called Maybe It’s Me.

- KILLING MAUDE: I left The Simpsons for two years to pursue my own projects. When I returned, in 2000, we were working on a Ned Flanders scene and I pitched a line for his wife, Maude. Everyone looked around guiltily, and writer Ian Maxtone-Graham finally admitted, “We killed her.” Why? Because the actress who played her asked for a raise.

Maude died in the 1999 episode “Alone Again, Natura-Diddily”—she was shot in the face with a T-shirt cannon and knocked over the back wall of an auto speedway. Some critics liked the episode, but it also received the full spectrum of knocks, from “harsh and cynical” to “sappy and lame.” One critic even said, “Killing Maude was a sin.” I have to agree with that: we killed the nice wife of a nice guy, leaving his two nice but annoying kids motherless.

When we make a big change like this—Apu having octuplets, Patty and Selma adopting a baby—we always think we’ll get some great episodes out of it. We rarely do.

A few years later, we were doing a show where Krusty gets bar mitzvahed; the episode was supposed to begin with Krusty’s father, Rabbi Krustofsky, dying. Finally, someone asked, “Why are we killing off all our great characters? The bloodshed must stop!”

Krusty’s father was spared.

We killed him ten years later.

BEST EPISODES EVER (IN MY HUMBLE OPINION, WHICH IS BETTER THAN YOURS)

“Marge vs. the Monorail” (season 4): Conan O’Brien came in with this story on his first day at The Simpsons. Script by Conan, directed by Oscar winner Rich “Zootopia” Moore: no wonder it’s a classic.

“The Father, the Son, and the Holy Guest Star” (season 16): Homer becomes a Catholic—why did it take us sixteen years to hit on this idea? And here’s a line you don’t hear often: Liam Neeson was hilarious.

“Radio Bart” (season 3): Matt Groening pitched this great story where Bart falls down a well. Terrific direction, Sting duets with Krusty—we lost our first Emmy Award with this.

“The Seemingly Never-Ending Story” (season 17): A story within a story within a story . . . within a story! You don’t get that on SpongeBob.

“Treehouse of Horror VI” (season 7): For years, one segment of every Halloween show kinda sucked. We usually stuck it in the middle. Treehouse VI was the first to have three great segments. Plus 3-D Homer! And Paul Anka!

“Simpsoncalifragilisticexpiala(Annoyed Grunt)cious” (season 8): Al Jean always wanted to do a Mary Poppins parody. I fought him on this for five years—thank God I lost. It’s the most popular thing we ever wrote together.

“King-Size Homer” (season 7): Fat Homer is funny. Really fat Homer is really funny. Look at Peter Griffin.

“Lisa the Skeptic” (season 9): There are only two seasons of Simpsons episodes I didn’t work on, and I’m afraid the show is smarter and funnier without me. This one is my favorite.

“Last Exit to Springfield” (season 4): I told Jay Kogen, who cowrote this with Wally Wolodarsky, that USA Today had named it the best Simpsons episode ever. He laughed. “It wasn’t even the best one we wrote that month.”

WORST EPISODES—EVER!

“Breitbart/Dumb Bart” (season 27): To impress Milhouse, Bart says that Homer sells nuclear secrets. Calling Milhouse a “high-level source,” this fake news makes it to Breitbart, and ultimately the White House. Homer is sent to Guantanamo, where he goes on a hunger strike. It lasts fifteen minutes.

“Seoul Train!” (season 12): The Simpsons are going to South Korea! They visit an animation house, never realizing it’s the one where they themselves are animated. Bart befriends the other ten-year-olds who work in the studio and convinces them to quit. Also, Maggie crosses into North Korea and launches a missile.

“The Simpsons/SpongeBob Crossover Spectacular” (season 8): After Mr. Burns dumps toxic waste in Springfield Harbor, the whole cast of SpongeBob SquarePants is forced to move in with the Simpsons. Marge immediately warms to Bob as “the best kitchen sponge I ever used.”

“King of the Hillary” (season 28): Severely misjudging the political climate, the Simpsons writers produced this Inauguration Day special where Trump lost the election. The show features Lisa and Bill Clinton playing the sax at Hillary’s inaugural ball, while an embittered Trump becomes Grampa’s new roommate at Springfield Retirement Castle.

“World Cup Sucker” (season 15): Homer reads an obviously fake list of Krusty’s Worst Episodes Ever—and falls for it. What a moron!