ESTABLISHING YOUR CRITERIA FOR FULFILLMENT

“While being a college dean was gratifying, I realized that my heart was really in the classroom, helping educate students in the biology of life.”

—A COLLEGE DEAN RESIGNING HIS POSITION TO RETURN TO CLASSROOM TEACHING

“Why is relationship a top value on my list and not among your top seven?”

—QUESTION ADDRESSED BY WIFE TO HUSBAND IN A VALUES ASSESSMENT PROCESS

“It’s sobering to see how out of kilter my core values are with the way I’ve lived my life.”

—AN EXECUTIVE REFLECTING UPON A VALUES CLARIFICATION PROCESS IN A LEADERSHIP COURSE

Matter of Life Success

Matter of Life SuccessHow do you know if you’re being successful in life? Answering that question is key to having a fulfilling life in your senior years. During your years in full-time work, success was probably determined largely by the imperatives of the workplace and the pressing responsibilities of home life. Success in the workplace, however, tends to leave precious little leeway for individuality. You either perform to the required standards or look for a new situation. Failing to adjust to minimally acceptable standards or acting out of character with company expectations earns condemnation via poor performance evaluations or even loss of a job. Business owners and senior executives in the private sector are clear about what success means. It’s a bottom-line proposition. Failure in that arena means going out of business or being demoted into obscurity.

On the home front, you may have had kids to raise, family expectations to fulfill, or social obligations to meet. More than likely, success in your personal or home life has not been as easy to measure as it was at work. At home, there was no promotion or raise to earn for paying the bills on time or emptying the dishwasher or consoling a disappointed child. Yet at times, you may have felt that success at home was all that really mattered, even if it was intangible. At other times, you may have thought that there was no way you could ever feel successful at home—it was all you could do to keep hanging in day after day. Regardless of how you’ve evaluated your success at home and at work over the years, you will need to come up with some new criteria for feeling successful in senior life.

The Changing Nature of Personal Success

The Changing Nature of Personal SuccessThroughout our early and mature adult years, success is pretty much determined by exterior conditions such as the expectations of the times and the culture in which we live. Either we adapt to the imperatives of our external world or face the stigma and consequences of failure. But this all changes when we reach the senior stage of life and enter the realm of the “retirement years.”

In senior life, our future no longer depends on performance evaluations at work, our dependent kids have become self-supporting adults, and we have achieved at least some degree of financial independence. Having newly acquired the freedom to choose the life we want, we now become confronted with determining what success in this new stage of life will look like.

Is it enough just to get out of bed and be here yet another day without any seriously debilitating ailments? Does success mean getting your golf game down to a low handicap? Or is success setting your own schedule without having to report to anyone else? Isn’t just being alive, having a good cup of coffee and a newspaper (or a TV if you’re more of a watcher than a reader), and a nice place to sit sufficient in itself? Is everything else just frosting on the cake? Why not simply settle for being grateful that your name doesn’t appear in the obituaries on this particular day?

Prior to reaching the senior stage of life, most of us have not spent a lot of time deeply pondering the issue of what constitutes a successful life. Sure, we had some societal expectations guiding our choices about things like career development, marriage, children, a good home, and where to go on vacation. In senior life, however, we are no longer bound by the many standards, expectations, and needs that ruled our earlier years. At some point, probably around fifty-something, we graduate from a life dominated by obligations to a life with more freedom to do as we please and become the person we’ve always wanted to be. But this new freedom also opens us up to the old existential quandary: What is the good life? To answer that, we have to know what we want.

Life Drift Preventative

Life Drift PreventativeAs seniors, we need an internal reference for knowing what leads to a sense of fulfillment and what will enable us to reach the end of our lives with the fewest possible regrets. Having clearly defined criteria for success enables us to live each remaining chapter in our life with the self-reassuring knowledge that we are fulfilling our ultimate purpose in life—achieving self-realization.

It is important to remember here that in this context achieving self-realization does not mean living as a self-centered ingrate. To the contrary, true self-realization means living in full-out awareness of and gratitude for the gifts that we have to share and enjoy. Awareness and gratitude go hand in hand. It’s hard to be thankful for gifts that we are not aware of having received. So as we leave our former obligations behind, we need to develop a new kind of awareness—one that grows out of an internal sense of who we’ve come to be and why we’re here. Otherwise, we could find ourselves in a state of drift, reduced to the brittleness of dried leaves blown about by the cold winds of meaningless existence.

Gratification vs. Fulfillment

Gratification vs. FulfillmentFor many years I served as the director of a career assessment and planning center at a large, urban community college that served both traditional college students and adults in career and life transitions. We also provided counseling services to members of the college community, including professors, administrators, and support staff who were feeling plateaued in their work and were looking for new directions in their careers and lives. To better serve these individuals, I created and delivered a series of life/career-planning seminars. These courses provided students with opportunities for reassessing their aspirations and career directions through various self-assessments, options exploration, and goal-planning activities.

Following one of these courses, the college community was shocked when a dean announced he was resigning from his position to return to classroom teaching. Why, asked his many colleagues, would anyone give up the perks that went with his position—better pay, more prestige, a bigger office, and a designated parking spot? The reason, he told us, was that while being a dean was gratifying, it was not fulfilling. As a result of the career/life-planning seminar, he realized that his heart was in the classroom, not behind an administrative desk guarded by an executive secretary. First and foremost, he said, he was an educator who wanted to turn students on to biology, a subject matter about which he was passionate.

Another example of life-changing awareness grew out of a coaching situation I had with a corporate executive. He had come to see me about a problem that was knotting him into a tangle of indecisiveness. His dilemma was over which of two altogether different courses of action to pursue in his career. On the one hand, he was being pressured to move into senior leadership within the organization. But for that to happen, he would have to diversify his managerial experience, requiring him to take on jobs that had only a modicum of interest for him. On the other hand, he’d been working professionally in a position for which he felt a great deal of passion. The nature of this work involved providing direct assistance to a clientele in critical need of his services. There was also a problem with this path, however. He had been in the same position for too long, according to senior management. The crux of the situation was that he wanted to be an executive but not quit what he loved doing in his current position.

I couldn’t tell him what to do, of course, but I did ask him how long he expected to live. He immediately reacted by saying he didn’t know, and, furthermore, why would I ask such a question? So then I asked him to intuitively give me his best guess as to his age at death and told him that the reason for my question would soon be clear. Okay, he said, he thought he would live until about the age of 87. Next I asked him to envision himself on his last day on earth, at the age of 87. With that as his perspective, I asked him to imagine that he had done what was needed to achieve his promotion to senior executive status and to play that out, like a movie of the mind, through the years right up to his last day on earth. Next, I asked him to mentally play out a second scenario, this one staying with the work he loved. What, I asked, did that feel like over time? Finally, I asked him to check out any other images that might come to mind and again mentally follow such a scenario through to his last day.

When he’d done all that, I asked him to compare all of these scenarios to see which possessed a greater sense of personal fulfillment. After mulling that over a few minutes, he looked me intently in the eye and informed me that he was clear about what he must do. As it turned out, achieving that promotion for him was not the path of ultimate satisfaction. His work was what mattered to him most. But to his surprise, he’d come to realize something else important. Through this process he’d gotten in touch with a strong need for autonomy. He would end up with serious regrets, he feared, if he didn’t resign from his organization to create his own consulting practice. His consulting, however, would focus on the type of work he loved and had been doing.

These two vignettes reveal an important message about what’s involved in living a fully successful life—namely, not to confuse gratification with fulfillment. Gratification is a reaction associated with achieving a need for some fancy that may have been prompted by media advertising. The job of advertising, after all, is to create within us a desire for something we don’t truly need, like a car that will make the neighbors envious or facial cream guarantied to make us appear forever young.

Fulfillment, in contrast, is enduring. It’s associated with a successful experience that leaves us with a rich memory. Gratification and fulfillment both feel good, but they resonate at different levels of the inner world. It’s gratifying to win the lottery, get a promotion, have a great dinner at a fancy restaurant, receive a nice bonus at the year’s end, or hit a lucky shot onto the last green. But our sense of satisfaction from such things usually tends to vanish rather quickly. How long does our excitement about a new car or sofa or golf club last? A week? A month or two? Sooner or later, the novelty wears off and we’re on to something else that has seduced us. Not so with something that is truly fulfilling.

We feel fulfillment when we experience something that connects with our core values. To live a fulfilling life, therefore, we need to listen to the heart—a heart enriched with a good measure of experience, a little bit of wisdom, and a lot of self-knowledge. Fulfillment occurs in the moment and also remains in long-term memory. We know that what we’re doing feels good, deep down in real time, and we remember it with fondness.

For Ginger Rogers, fulfillment must have come from a well-executed step that connected with her need to dance and dance well. For my friend Mary Kaye, fulfillment came when she discovered her core value of creativity and found the right expression for it in making “Indian” jewelry. Now she has another type of fulfillment to deal with—meeting the rapidly increasing demands for her lovely products. Gloria, a counseling psychologist, feels a sense of fulfillment by connecting her core value to meaningful work. She feels energized when she helps individuals resolve issues causing emotional pain and then helps them move on to exciting new directions in their lives.

What do you recall as being life-enriching experiences from the past? What might create fond memories in your future?

Who Determines Your Success?

Who Determines Your Success?Who has determined your success in the past? Has it been your boss, your financial planner, or your friends? From the grand vantage of hindsight, I’ve come to realize that it was my father who I was desperately attempting to please throughout my young adult years. As I’ve mentioned previously, Dad was sole owner of a successful business that kept him preoccupied with business concerns until shortly before he died from prostate cancer at the age of 69. Physically he was a large man who I, and many others, found to be an intimidating presence. This was made all the more pronounced by his generally sullen, detached manner. He was also work-driven—off to his business early in the morning, home late at night, seven-days a week, with little time for involvement in family matters. Family was my mother’s domain. The way I processed all of this left me with a subconscious obsession to please my dad. I wanted him to notice me and give me some attention. So I tried to earn his attention through stellar achievement. How else could I make him proud of me? What else would prove that he loved me?

It took a major failure in my life, which induced me to undergo counseling, for me to become conscious of my obsession and recognize the sheer folly of it. Finally, at the age of 33, I was able to let go of this obsession in favor of a more authentic, inner reference for defining my success. As an interesting side benefit of freeing myself from my old obsession, I realized that it was actually the image of my father that I had in my head that I had been trying to please—not my real father. In reality, my father had loved me all along; he just didn’t show it in a way that I was able to recognize at the time.

It’s not unusual for younger males to think that they must please, exceed, or rebel against their father in order to succeed. The image a person has of his or her mother also may be a benchmark for determining whether one is successful. A mother issue, in fact, was at the source of a problem for a client I counseled a few years back. His presenting, or “surface” issue, was that he wanted help for getting into the CEO track. But, in discussing his aptitude and motivations for that, it became rather obvious, to me at least, that this was a hollow objective. He lacked the fire-in-the gut motivation that such a goal requires. In exploring that with him, it turns out that he’d somehow come to the conclusion, for whatever reason, that the way to make his mother proud was to become a chief executive officer. The essence of his real aspirations, however, was something extremely different. Having understood it was a fantasy mother in his head who he’d been endeavoring to please, he made a rather dramatic shift in his career plan. Instead of trying to become a CEO, he embarked upon a plan to become a disk jockey. I don’t know if he ever realized his new dream, and if so, if that made his mother happy. What I do know is that he left my office unburdened from an unrealistic expectation. He walked out happy with a new, more realistic dream that was more in line with his personality and talents.

Mothers, fathers, and grandparents—they often have strong aspirations for their progeny. Spouses also frequently want their mates to succeed in the dreams that they have for them. How many spouses have urged a mate to do what is necessary to ascend the corporate ladder? How many parents have slaved away at unfulfilling work or extra jobs in order to be able to send their children to expensive colleges or universities? How many, for that matter, have stood in long lines to get their children enrolled in the “right” preschool? Who wants their children left behind in the race for the keys to success in our materialist culture?

A good friend of mine, an ex-Catholic priest, left the church to marry a woman he loved and to pursue a career in a suit rather than a robe. My friend, whom I’ll call J. P., confided in me that he knew his actions would be the death of his mother. J. P.’s life as a Catholic priest fulfilled the lifetime dream his mother had held for him. She simply could not find it in her heart to forgive him for what she considered to be his unpardonable sin in abandoning the priesthood and smashing her pride in his prominent status in the community. His mother was so bitter, in fact, that she refused to attend his wedding. She died shortly after that, perhaps of a broken heart. It took courage for J. P. to break through the pain and disillusionment he felt at his mother’s refusal to grant him the right to his own life. But he knew that he had to live his own life in a way that was fulfilling for him, rather than for his mother and her unfulfilled dreams.

I myself confess to wanting my oldest daughter to become a child psychologist. Fortunately for her, she has had the good sense to follow her own guidance in another direction, one that heeds her own calling rather than her father’s wishes for her. Undertaking a major life transition is the time to reassess who has unduly influenced your quest for success in the past. Once you’ve figured that out, you are ready to decide who it will be in the future.

Use the following checklist for help in getting a clear picture of who has had excessive influence on your quest for success. You might begin by first checking anyone who has served as a defining agent of your success efforts in the past. Next, circle anyone who will serve as a significant inspiration for or judge of your success in the years ahead.

Mother, father or other parental authorities

Mother, father or other parental authorities

Spouse or significant other

Spouse or significant other

Role model(s)

Role model(s)

The boss

The boss

Colleagues at work

Colleagues at work

Professional peers

Professional peers

Former teachers/professors/mentors

Former teachers/professors/mentors

Religious community

Religious community

Contemplative community

Contemplative community

Civic community

Civic community

Children

Children

Grandchildren

Grandchildren

Friends and acquaintances

Friends and acquaintances

Physician

Physician

Work group

Work group

Cultural and/or family heritage

Cultural and/or family heritage

Sports/recreation buddies

Sports/recreation buddies

Pub or tavern buddies

Pub or tavern buddies

Bridge club or other such group

Bridge club or other such group

Historical or legendary heroes

Historical or legendary heroes

A dream idol or famous person

A dream idol or famous person

Neighbors

Neighbors

A spiritual guru

A spiritual guru

Therapist

Therapist

Paramour

Paramour

Ego, sense of personal pride

Ego, sense of personal pride

Authentic self

Authentic self

Other ________________________

Other ________________________

Core Values and Ultimate Success

Core Values and Ultimate SuccessNow that you have focused on those you have chosen or allowed to inspire or judge your efforts at success, let’s explore what’s needed for you to experience fulfillment. I’m not referring to small successes here and there, although they are important and can add up over time to a substantial degree of success. What I’m referring to here is the kind of ultimate success that you want to be thinking about at this stage of life. This kind of success not only entails knowing that you’re living a fulfilling life in the current moment—it provides fulfillment from the perspective of our final life review. Ultimate success is a profoundly personal experience: It can only be distilled from the you that flows directly from your core values.

Could you experience true self-fulfillment if the manner in which you were investing your life’s resources (including energy, time, knowledge, wisdom, money, and personal/profession development) failed to connect with what you value most dearly? Imagine, if you will, someone who abandons a core value of autonomy for the sake of convenient employment in an organization where she reports to others in a role of hierarchical dependency. Certainly the basic need for employment would be met, but it would come at a high cost to well-being.

No matter how well we think we have succeeded in a given situation, success is doubtful when self-motivation is lacking. Self-motivation leads to that critical sense of congruency, of being true to yourself. If autonomy is a high-order priority, you owe it to yourself to find a way of becoming your own boss. My friends Sarah, Dan, and Thad are good examples of people who found ways of doing just that. All three had tried working for others but simply couldn’t deal with being at the beck and call of someone else. They had to do their own thing. For Sara, that involved becoming an independent consultant. For Dan, it was creating a unique, one-man business. And for Thad, it was buying commercial real estate, fixing it up, and selling it at a nice profit.

Have you ever made a remark about someone having no values? The truth is that we all have values; we just don’t share the same set. As individuals, we may be inclined to think of our values as the “right” ones and the different values of someone else as “wrong.” When people with one set of values vie for dominance over people with a different set, we often end up with conflict in families, communities, and the world. But values conflicts also occur within an individual.

If you’ve ever found yourself paralyzed by a choice you needed to make, the likely cause was that two deeply held values were in conflict. The previous story I shared of the executive in a quandary over which course to pursue is an example of an interpersonal values conflict. He was stuck between a desire for promotion and the need for work that was a heartfelt service. He resolved his conflict only when he realized which value outranked the other.

Values form the basic structures of our personal beliefs, determine organizational policies, and define national priorities. Some folks and some factions of like-minded individuals feel so convinced that their values are so supremely “right” that they feel duty-bound to impose them on the world, or at least their world. As we see everyday, there are people who have few qualms about killing those whose values they can’t tolerate. Consequently, we have witnessed all too many examples of ethnic cleansing, religious wars, and deadly family feuds. We also have seen what happens when values issues become so highly charged and propagandized that a Right to Life advocate murders a Right to Choice activist, or when so-called peace demonstrators riot and ransack an urban district.

On a more positive note, we also have seen individuals with shared values coming together to promote good causes. The green movement, Doctors without Borders, and Save the Whales are just a few of the thousands of values-driven associations doing good things on our planet. We can only hope that we will see more individuals, groups, organizations, and countries adopt value systems that are based on compassion, tolerance, and serving the common good.

We all are subject to intensive values programming throughout our early years. In fact, by about the age of 20, our values are pretty much cut, dried, and applied. By then we are convinced that we know what’s good and bad, right and wrong, acceptable and not. We’ve been fed the values for making these determinations by our family, culture, particular environment, education, and religious/spiritual affiliation—not to mention the constant bombardment we receive from the media. Much of our values programming has occurred at the subterranean level, so that we are usually not conscious of the huge amount of indoctrination we’ve absorbed from all these sources.

After the age of 20 our values may change, but not easily. It takes a psychological knock on the head or a significant emotional event to cause us to examine our early programming and values system. Life does, of course, present us with any number of such events, but even then we may resist taking a close look at the values that shape the choices we’ve made. We might be afraid that examining our values system will lead to changes that result in changing our whole life structure.

Let’s say, for example, that we were values-programmed with admonitions to “always work hard, do what you are told, obey proper authority, don’t trust minorities or folks over 50, go about your own business, and stick to your guns.” No matter how much we attempt to live by these values, there is little likelihood of their providing richly satisfying outcomes. Some of us have been fortunate to receive values programming that supports life satisfaction; we may have grown up with revered role models for values like “It’s better to give than to receive,” or “Abide by the golden rule,” or “Follow your dreams.” Virtually none of us, however, has been value programmed so wisely and well that we couldn’t benefit from an examination of what’s at the core of our motivations and feelings and make some adjustments.

Core values serve as operational guidelines for behavior, influence our views of others, and become the basis for our judgments and moral principles. Although values are not the sole impetus for behavior (personality style, habits, and attitudes about life are some other influencing factors), they are a primary determinant in matters both large and small.

Values play a key role in how big a tip you leave, how you treat others, what career path you’ve chosen, and who your heroes are, both in politics and legend. Values influence your judgments about others and become the basis for your self-judgments. The little voice that natters away incessantly in your head may be an indication of how well your actions conform to your values priorities.

For example, I have a little voice in my head right now, as I write this, nattering away about violating my vow to let go of 20 pounds. After I consumed a chunk of dark chocolate and washed it down with a double latte, a little voice piped up and said, “Don’t you have any willpower? You should be ashamed! Unless you can control your eating habits, you’re going to end up pudgy.” If I had snacked on some fruits and nuts instead, no doubt I would have heard a little voice with a self-congratulatory message like, “Good choice! You bypassed instant gratification for long-term satisfaction.” It may be important to listen to that little voice in your head for clues as to the values it speaks to.

Values influence and drive our behaviors in any number of ways, both consciously and unconsciously. I recall a rather humorous example of that. I was standing at a busy intersection in downtown Chicago a few years back while attending a national convention of the American Counseling Association. This was a huge convention attended by several thousand professionals, and scores of presentations were taking place in a number of hotels. In a rush to get from one hotel to another, I was impatiently waiting for a traffic light to switch from red to green so I could cross the street and get to a presentation I really wanted to hear. A quick glance up the street informed me that traffic was conveniently backed up enough to give me enough time to cross the street against the red light. As I began to cross the street, a woman standing next to me saw what I was doing and also began to cross the street. She took only a few steps into the street, however, and then I heard her say out loud, “But it’s red.” With that, she retraced her steps to the curb to wait for the green light she needed to sanction her crossing.

What strikes me most about this little episode is how our values influenced our behaviors. For me in this situation, a value involving intellectual stimulation took precedence over strictures for regulating pedestrian street crossings. I want to be clear here that I consider myself to be a law-abiding citizen. In this situation, however, one of my other values topped the one admonishing me about the risky business of crossing at an intersection against a red light in the downtown traffic of a major city. The woman on the curb also appeared to be attending the conference and may well have been heading to the same presentation. But for her, a personal value of obeying the law took precedence over getting to a presentation in time to hear a leading psychologist whose life work had done much to contribute to a more humane world.

At times we need others to help make us aware of what’s really important. I was reminded of this in a recent coaching situation with a work-obsessed executive who is also a devoted husband and father of two young boys. Our discussion focused on his agenda-driven proclivities that carried over from work into his home life—with some significant benefits and some severe costs. One benefit was that he used a to-do list to help him be handy around the house. He was constantly fixing or improving something. The bad news also dealt with his to-do list. He was so obsessed with getting things done that he found it exceedingly difficult to relax and have fun. Somewhat chagrined with himself, he confided that he had recently been “too busy” to take time out to accommodate his wife’s request to go for a little ride for a few moments of unstructured time together.

Around the same time, his wife intercepted him as he was about to head out the door to purchase some additional materials needed to complete his current project. When she heard that he was off to the hardware store, she blocked his way and insisted he take one of the boys along, to which he consented. Reflecting on that episode, he realized that the short time he spent with his son turned out to be a significant bonding moment. In retrospect, he learned that time with his sons was far more valuable than any satisfaction he would ever get for finishing a project on his to-do list. Thanks to his wife’s timely interventions, he became more aware of his values priorities. He let go of his old programming to be constantly productive and began to be proactive in seeking other opportunities to enjoy his family.

How might your values be influencing your behavior? Does the programming you got about being productive frequently overrule how you respond to situations involving relationship or being in service to others? Has a value for career advancement ever caused you to violate a personal ethics value? Have you ever stood up for your value of a “committed relationship” by taking some action that has jeopardized a friendship or career advancement? Have you had a tendency to let daily routine and the tasks at hand preoccupy your attention to the exclusion of an alternative that might ultimately be more satisfying? If any of these situations fit you, it might be time to reexamine and reorder your core values. Are you ready to act on your deepest values in your daily action?

Entering life as a senior citizen is definitely one of those “significant emotional events” calling for values reassessment. As I enter my seventh decade, I realize that my values priorities are no longer exactly what they were in adolescence—or even in my twenties and thirties, for that matter. Over time, spirituality, generativity, and health have all migrated out of my psychic backwoods to premier spots in my values landscape.

In our earlier days value priorities tended to focus more commonly on concerns around relationship, career, child-rearing and/or home-building, and identity clarification. Significant events may have altered our values priorities over time—maybe without our even being aware of such changes. But the most typical scenario I’ve found in my counseling practice is that when it comes to career and life choices based on our values, most of us have unconsciously cruised along the same roads that we did 20, 30, or even 40 years ago. Moreover, if we haven’t been actively repairing and improving those roads over the years, they are probably in pretty bad shape by now. Over the years, we may have changed jobs, residences, cars, friends, wardrobes, entertainment venues, diets, and, yes, even mates, a number of times. But when, in all that time, have we even given a thought to updating our values?

When, for example, did you first decide to marry, and what were you seeking? Were you looking for companionship, a generous provider, a good-looking mate, someone with compatible religious beliefs? What would you look for today? When did you decide initially to pursue your career, and what was the basis for your decision? Was your choice based on money, fame, power, or the desire to change the world or affiliate with an organization you greatly admired? What would guide your choices today? The values priorities of your youth may have little relevance to the kind of fulfillment you want in senior life.

Over the years I’ve counseled scores of individuals in their senior years who have, in effect, remained prisoners to decisions made early in life, even when it later became apparent that these were poor decisions to begin with. Some remained with an unsuitable partner, career choice, or organization, even in the face of a significant gap between their values priorities and their current life choices.

One such individual was a medical doctor in his late forties who had been encouraged by colleagues to come see me. As a part of the counseling process that followed, he completed an assessment that showed strong proclivities to creativity. In reacting to his assessment results, he confided that in his early years he’d really wanted to pursue a career in the arts. His father, however, put the kibosh on that aspiration. His father refused to pay for an education that was only going to “relegate his son to the ignominy of becoming a starving artist.” Honoring his father’s wishes, he’d gone on to develop a successful medical practice. That, it turned out, was a choice that made him occupationally successful but emotionally unfulfilled. No matter how hard he tried, he simply could not get his heart fully into his work. Unfortunately for him, he felt it was too late in his life to make a change to pursue his passion in the arts. He would have to postpone such aspirations until retirement, he concluded, as he was just too much invested in a successful practice.

This story ends with an interesting twist. A few days after our last session and his decision to let the momentum of his past continue to dictate his future, he came back to see me. But, this time, not for himself. He asked if I could provide him with a couple of the assessments he’d taken to give to his adult kids, who were about to enter graduate school. Handing him the assessments, it occurred to me to ask if, by any chance, his kids were headed into the medical profession. With an ironic grin, he said, “Yes, and guess who was behind their decisions?” His reflections on his own personal experience led him to reprioritize his values about directing his kids’ career choices. He had come to appreciate that personal satisfaction was a higher-order criterion for personal success than a father’s values about security or vanity.

Your Criteria for Personal Success

Your Criteria for Personal SuccessUltimate success depends on making decisions that enable you to live congruently with your most precious values. That, of course, requires clearly knowing what your core values are and getting your values priorities straight. “Assessing Your Criteria for Personal Success” is designed to help you clarify and prioritize those values that are core to determining how successful and fulfilled your life will become in your next chapter of life. It is divided into three parts:

Part I: Assessing What Success Means to You

Part II: Prioritizing Your Personal Success Criteria

Part III: Applying Your Criteria for Personal Success

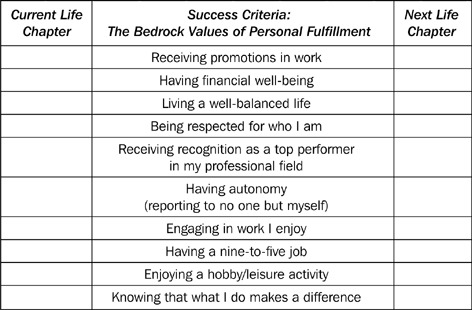

In Part I, you will assess what defines your success in your current life by assigning a rating to each of the items in a list of Success Criteria. Then you will rate each item for how important you want it to be in the next chapter of your life.

As you work through the process in Part I, you may discover that values priorities for your future do not match perfectly with those from your past. Seeing and understanding such differences will enable you to see where there is compatibility and where there’s incongruity. Where there is compatibility between old and new values priorities, you can expect smooth sailing into a new life. It’s where the gaps exist that you will want to pay special attention. It’s there that you will need to make adjustments if you are to accommodate to a new way of being and doing. Part II will help you do this.

For instance, what if “Living a well-balanced life” came out as a top priority for your future but has not been so in the past? You might yearn for better balance but find yourself working against the currents of past obsessions, habits, and programming. Your early life scripting can make a desired lifestyle change so uncomfortable that you simply give up trying to change things and give in to old habits.

I find that rescripting my values programming involves a lot more than my good intentions. This became even more readily apparent to me the other day when I was talking with a friend who retired a few years ago after being a college English professor for 35 years. He was telling me how hard it had been to change his own deeply ingrained programming. In the process, he told me about a recent epiphany he had had.

“You know, David,” he said, “for the first time since retiring, I am no longer feeling driven by the need to be productive.”

Still experiencing the self-generating pressures to be productive, I couldn’t help but be envious of his newfound freedom. How, I asked, did he get to this more relaxed, less obsessive state? His answer: Knowing what he wanted, how he wanted to be different, and acting on that agenda. There is, he added after a moment’s reflection, something else—to be patient with yourself. That seems to be excellent advice, and I’m “working” on it.

Before moving on to Part III, stop and evaluate where you are. What differences do you note in your values priorities from your current life versus those in the next chapter of your life? Note where there are congruencies and differences on your two lists. Comparing the two lists can reveal what’s going to be easy and what might be tough in making the transition to your new life.

Perhaps you see that working for a cause you care deeply about has been and will continue to be a high priority. Or maybe you discovered a mission for which you’ve had a passion, but until now, had little time to devote to it. Such was the case with a client of mine who loved to work at a shelter for injured animals (hawks with broken wings, foxes missing a leg, wounded deer, and such). Before retiring she was able to find only a few hours here and there for this passion, but she was eager to devote a great deal more time to it in retirement when she could align her passion with the way she spent her time.

Where are the differences on your two lists? Is “being creative” a top priority for your future but not to be found on your current list? If that is the case, you may need to decide in what ways you want to be creative. There are many avenues for expressing your creativity, such as creative writing, quilting, watercolor painting, or creating games for Alzheimer patients—all of which were new life directions taken by retirees with whom I’m familiar.

Once you have identified your values for the next chapter of life, you will want to prioritize the core values for your future. A helpful process for achieving this objective is to evaluate aspects of your current life for insights to the future. Part III, “Applying Your Criteria for Personal Success,” will help you with this objective.

As you take the following assessment, and especially as you work through prioritizing your values, you will probably find some comfort zones and some unexplored territory for your senior years. Whatever the results, just remember to be patient with yourself.

The following assessment is designed to help you clarify and prioritize those values that are core to determining how successful and fulfilled your life will become in your next chapter of life. Follow the directions to complete each of the three parts and use your results as a basis for discussion, where appropriate, with your partner or significant others.

Step 1: Assess what defines your success in the current era of your life by assigning a rating to each of the items in the list of Success Criteria.

• Use the following rating scale to record your choices in the left-hand column headed “Current Life Chapter.”

• Use the blank spaces at the end of the assessment to add any additional items that should be on your list.

Assessment Rating Scale for Success Criteria

4 = completely true for me

3 = significant degree of relevance for me

2 = some relevance for me

1 = little relevance for me

0 = absolutely no relevance for me

Step 2: Review the list of Success Criteria again and rate each item for how important you want it to be in the next chapter of your life.

• List your ratings in the right-hand column headed “Next Life Chapter.”

• List any additional criteria you deem important to your future in the blank spaces at the end of the chart.

Part I: Assessing What Success Means to You

Directions for Part II

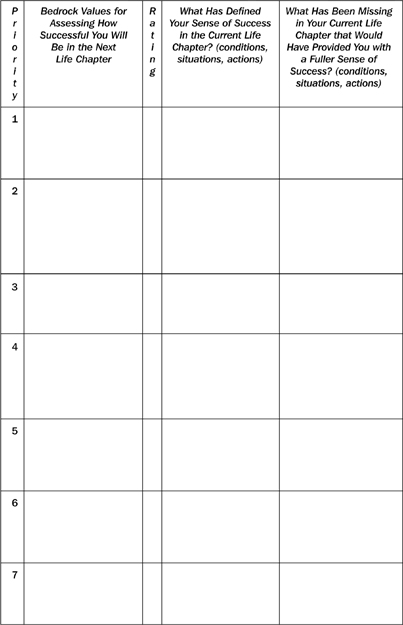

From your assessment results, complete the following chart to determine your values priorities from your current life chapter and those that you intend to establish as your priorities for your next life chapter. As much as possible, identify and list your values in priority order. Which single value do you hold most deeply? Which is next? What’s after that?

This may not be an easy task. You may find many values competing for top billing on the current and futures stages of your life. Should you find that narrowing your list down to the top 10 might be too challenging, you might wonder why you should bother. Don’t give up!

Here are some ways that having clearly defined and prioritized values can benefit your quality of life:

• Making choices and decisions with better prospects can lead to a sense of personal success and fulfillment.

• You can learn to manage your behavior so that it’s congruent with what’s most important to you at this stage of your life.

• You can minimize inner conflict by understanding which inner motivations competing for your attention take precedence over others.

• You can manage stress and conflict with others by knowing what issues connect with values you are willing to go to the mat for, and which issues you can let pass by with minimal engagement on your part. In other words, clarifying your values priorities provides key insights for knowing which battles you are going to fight and why. You will also be more adept at identifying which issues you are going to minimize or ignore, and your reasons for doing so.

Begin the following process by first prioritizing what have been your core values in your “Current Life Chapter.” Then proceed to your desires for the “Next Life Chapter.” You might want to work with pencil and have a good eraser nearby, since you’re likely to be making changes as you think about your choices.

Begin by reviewing those values that you rated 4s in Part I for selecting your “top 10.” Draw on your intuition in completing this process and “trust your gut” in selecting your choices.

Part II: Prioritizing Your Personal Success Criteria

Step 1: From those core values you prioritized in Part II under “ Next Chapter of Your Life,” list your top seven values on the chart in Part III, “Applying Your Criteria for Personal Success.”

• Record your top seven values in the space “Bedrock Values for Assessing How Successful You Will Be in the Your Next Life Chapter.”

• As you transcribe this list, you might want to think through your values priorities again and put them into your own words.

Step 2: This step asks you to determine how fully those values you have identified as top priorities in the next chapter of your life are being met in the current chapter of your life. Use the following scale in making your determination:

Rating Scale

++ value fully satisfied in current situation

+ value mostly satisfied in current situation

+– value moderately satisfied in current situation

– value mostly unsatisfied in current situation

– – value completely unsatisfied in current situation

Step 3: Focus on the column headed “What Has Defined Your Sense of Success in the Current Life Chapter?” Use this column to determine as best as you can the degree to which a core value is currently being satisfied.

• If you have rated the value as being either partially or fully satisfied in your current situation, try to identify the conditions, situations, and actions that have proved satisfying.

• An example is provided for what a completed matrix looks like. For Bernard, for example, completing his personal success matrix helped him examine his current life situation and determine what would provide future fulfillment.

Step 4: Focus on the column headed “What Has Been Missing in Your Current Life Chapter that Would Provide You with a Fuller Sense of Success?”

• Use this column to determine, as best you can, what it would take in your current life situation to more fully satisfy your core values.

• You might again find Bernard’s sample profile to be helpful. It follows the form that you will use for “Applying Your Criteria for Personal Success.”

Part III: Applying Your Criteria for Personal Success

Bernard’s Example

Interpreting the Sample Criteria Application

Interpreting the Sample Criteria ApplicationTake a look at Bernard’s sample for ideas on how a completed report might look. The sample report reveals two ways in which the process was helpful to Bernard and can be for you:

1. Examining your current life situation helps reveal what may satisfy your core values priorities in the future. In that regard, note from Bernard’s sample report that a value of “Using and developing my top talents and strongest interests” has been partially met in his current life situation. He has met these needs by using his coaching abilities in his work with adults and by developing creative abilities through various writing projects. He plans, therefore, to continue with these kinds of activities in the future. It’s just that Bernard will be doing these things on his own from here on, rather than as part of a full-time employment situation.

2. Your current life situation may also provide insights into what’s been missing and what might have provided deeper satisfaction. Bernard, for instance, realized that his top value priority of “spirituality” was being only partially met and concluded that a disciplined meditation practice could more fully support that core value. Based on that realization, he started participating in a local Buddhist meditation group and weekly yoga classes. He also decided to explore more options within his own faith tradition and accepted an invitation to meet with a men’s breakfast group on a monthly basis.

Bernard wanted to make some minor adjustments but felt that he didn’t need to make any major changes at this point. If most of your values priorities are currently being satisfied, you might want to continue in your current situation, perhaps with some fine tuning here and there.

Or if your values priorities are being met but life circumstances have dictated the necessity for change, you might want to recreate something fairly similar to what you already have, as much as is possible within the parameters of your current life situation.

However, should your core values for the next chapter of life be completely unsatisfied in your current life, you would want to look at ways you could restructure your current conditions, situations, and actions.

Planning Together

Planning TogetherIf you are in a committed relationship and intend to remain so, a discussion with your mate about your values priorities assessment is in order. For a fruitful discussion, you would want your partner to complete the core values assessment process before the two of you compare and discuss your results. Both of you should be prepared for a rich and lively conversation!

From my experience in conducting many life-redesigning workshops, I’ve witnessed some rather animated interactions between partners reacting to differences noted in each other’s core values priorities. One such discussion involved a wife demanding to know from her husband why relationship was number one on her list but did not even appear among his top priorities. Surprised by her reaction, he responded that since he was already in a committed relationship, it didn’t occur to him to list it as a priority. His response did nothing to mollify her. In fact, it raised her hackles even more.

“If you don’t think our relationship important enough to identify it as a top priority,” she said, “how likely are you to give it much time, attention, and nurturing commitment?”

The husband finally saw her point and put “relationship” at the top of his core priorities. He had never intended to slight their relationship, but he had taken it for granted in his list of priorities. He had also allowed his introverted nature to blind him to the fact that just having good intentions is not enough. He also needed to let people—especially his highly extroverted wife—know what his intentions were. But, most of all, he needed to be expressly clear with himself about what he valued most. Otherwise, things that were of lesser value to him would slip in and take precedence by default.

If we are not consciously aware of our real values priorities, we tend to overlook them in favor of what has our attention at the moment. Relationship tends to be one of those overlooked areas that don’t make it on our to-do lists. That’s especially true for those of us who’ve been in long-term relationships.

Regardless of how long you’ve been in a particular relationship, if it truly matters, you and your partner could probably benefit from a healthy dose of renewal as part of a senior life rejuvenation effort. Life circumstances change dramatically when your career and family issues no longer demand your full attention. As part of your adjustment to new circumstances, you don’t want to fall into the trap of ignoring or trying to change your partner instead of the two of you working to change your life together. Nor do you want to miss the fun and fulfilling experience of seeing how you both have grown and matured, and how you can find new ways to share your dreams for the future.

Summing Up

Summing UpGraduating from a full-time work commitment invites a life redesign. Undertaking this process confronts us with the challenge of determining what will make our future—especially the next chapter of our future—fulfilling. Living a richly fulfilling life is a matter of making choices and taking actions congruent with our core values. We’re unlikely to feel highly successful if we are not achieving what we value most dearly.

Unfortunately, most of us pay little conscious attention to our personal values in the course of daily life. Most of us have felt pressured to subsume our individual values to those of our social institutions and cultural norms in order to make it in the world.

The transition into senior life offers a rich opportunity for greater freedom of choice. But achieving this new freedom requires that we consciously reassess and clarify our values priorities. Our personal values tend to change and evolve over the years so that few of us in our fifty-plus years are motivated from the same values that motivated our behavior earlier in life.

If you want real satisfaction and fulfillment in the next chapter of your life, you need to place a high value on values clarification.