Gamma said he knew the direction of the lake. He had seen flat blue water through the door of the luggage wagon. He led us through the high weeds, jumping every now and then to check his bearings. He made sure that we walked around the outskirts of the town and not through it.

Because I had convinced my wife that my experience with the train guard’s boot was trivial, she concerned herself with keeping the family together. If the truth be known, I could have used a little sympathy for my poor tail. It dragged behind, reminding me of my injury every time it encountered a small obstacle such as a dandelion bush or a dried twig. Roger walked beside me, full of cheerful talk.

“That’s the worst part of the journey over, Spinny, me lad.”

I did not respond to his prattle, and I wished he would move away. I lifted my tail over the roots of willow trees, and in a mood of blackness, I hoped that the luggage guard would get a thousand flea bites on the most tender parts of his body.

Roger went on: “After that train ride, a trip across the lake will be a piece of cheese.”

Alpha turned. “You’re forgetting about the giant eels, Uncle Roger.”

Jolly Roger snorted. “Pirate rats eat eels for breakfast.”

My tail may have been sore, but my nose was in excellent working order, and I sniffed the weeds and long grass for any sign of hidden cat. In several places I noted old dog pee and some mouse droppings, but there was no cat odour, and no nasty surprises. Past the willow trees, the earth smell suggested dampness, and I knew we were somewhere near the shore of the lake.

It was Alpha who had been given the memory task for Sunsweep Lake, and she, too, was sniffing the earth. “Don’t go near the water,” she said to her brothers and sister. She glanced back at Roger. “These eels eat rats for breakfast.”

We came to a clearing that was some kind of humming-bean camp on the shore of the lake. Through the last grass stalks we saw two houses on wheels and a small fabric house pinned to the earth with poles and ropes. There were no humming beans to be seen, but some of their coloured skins were hanging on a line between the two houses on wheels. The lake was as Delta had described it, calm and bright blue, with a shore on the other side at a distance of one city street—not far at all. If the water was full of rat-eating giant eels, they were well hidden below the smooth surface.

Alpha stepped out into the clearing and at once there was the shrill loudness of a barking dog. She jumped back into the grass. This was the worst kind of dog: a terrier that specialised in the extermination of rats and rabbits. But the noise stayed at the same distance, and when I put out my head to investigate, I saw a sharp-faced terrier jumping up and down on a rope fastened to a wooden kennel. The animal was tied and couldn’t reach us. We were in no danger.

We all came out to the shore of damp earth and grass that had been given a haircut. From our shadows, I estimated middle day. The sun overhead gleamed on the water and the air was still. Further along our side of the lake was a small colony of houses on wheels and a wooden jetty that looked as though a road had waded into the water and stopped, perhaps afraid of the eels. I suggested this to Alpha but she merely said, “Oh Papa, you’ve become very fanciful in your old age.” I realised then that my ratlets were growing up and could no longer relate to my funny baby rat stories. That fact, together with the pain in my tail and the barking dog, made me rather sad.

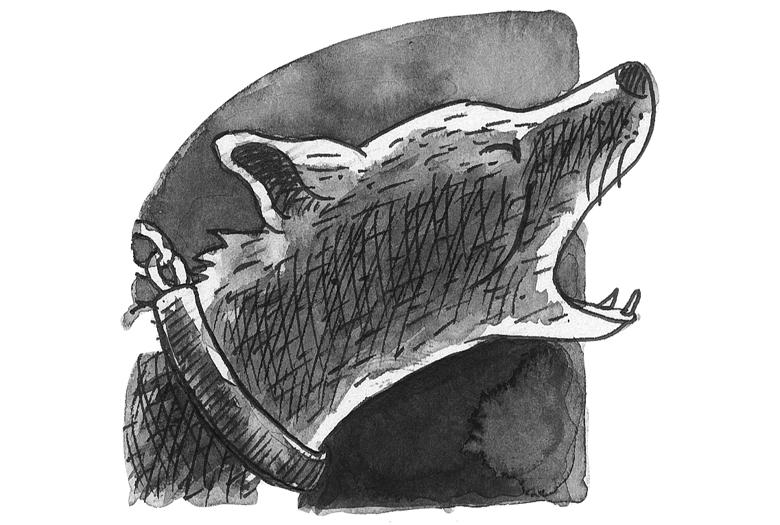

I was in a melancholy daydream and didn’t notice that Beta had gone to the water’s edge. She was thirsty, and as she bent to put her nose into the water, Alpha and Retsina shrieked. On the water in front of Beta there appeared a V-shaped ripple. She didn’t see it, but I did. I sprang forward, a great leap, grabbed Beta’s tail between my teeth and yanked her away from the lake’s edge. As I did so, a head broke the surface. I swear to you, my friend, that head was bigger than the head of a mature humming bean. It was shining greenish-black with pale, round eyes, a wide-open mouth and sharp teeth that sloped back into its mouth. The mouth snapped shut where Beta’s head had been. There was a great splashing in the shallows as a dark body as long and thick as a tree trunk turned in a semicircle. The tail scraped the bottom, stirring up mud, then the giant eel headed back to the depths.

Beta was shaking all over and squeaking with every breath. Poor little ratlet! No doubt, I was not the only one who now had a sore tail, but I had snatched her from certain death.

Retsina and Delta comforted Beta. Alpha said, “I told you not to go near the water!” Her voice was severe because she was also in shock. It had all been so sudden.

Delta informed us, “We shouldn’t be surprised that it almost came ashore. In wet weather, eels can travel over land from—”

“Stop! Stop!” Roger put his front paws over his ears. His mouth was drawn back from his teeth and his eyes were closed. “That’s enough! There’s no way you’ll get me over that lake. If you want to be eel bait, that’s your business. I’m setting sail for Sunsweep town and a cosy nest at the back of a tavern. Bye, shipmates! It’s been nice knowing you.”

He wasn’t bluffing. He was leaving us. He ran towards the long grass and, without so much as a word or wave of his tail, he disappeared. I was surprised, but without regret. The journey to Ratenburg would be much easier without Roger.

Delta looked thoughtful. “He had a point, Papa. How do we get across that lake? Are we capable of building an eel-proof boat?”

We were quiet for a while, all except Beta, who was still making an occasional sobbing hiccup, and the crazy dog that leapt on the end of its rope. “I’ll get you!” it was barking. “I’ll bite your heads off and spit out your brains!”

I ignored it. In my opinion, even pedigree terriers are ill bred. My concern was the giant eels. In good conditions, rats are capable swimmers, but none of us would last ten seconds in that water. A boat was needed. But what boat?

Alpha sat beside me. “Papa, the lake is my responsibility. Remember? I’m going over there.” She pointed her nose at the camping place. “I’ll find a boat for us.”

“Sweetheart, what would six rats do with a humming-bean boat?”

“I didn’t mean that kind of boat,” she said. “Something that will float. You know, like a big balloon.”

“Eels have sharp teeth,” I reminded her.

She patted me on the back. “I know that, Papa. I’ll return soon.”

I called after her, “Don’t go near the dog!”

Retsina and I watched Alpha run through the shadows to the houses on wheels. We knew that our daughter had much good sense, but she was also the one who took risks and we didn’t like the way the terrier’s barking changed to a coaxing growl. The dog was daring her to come closer.

After a while, Beta recovered from her frightening experience. I saw the marks made by my teeth on her tail, but at least her tail was still straight and not broken like mine. She did not mention the hurt. “Thank you, Papa,” she said.

Retsina also sat next to me. “Spinnaker, I’m anxious. Do you think Roger had the right idea? Consider our ratlets! Surely a nest in the town is safer than attempting to cross that water.”

“Darling wife, it’s you who has always had the dream of living in Ratenburg.”

She nodded. “I know. I’ve heard about it ever since I was a tiny ratlet, but I never imagined it would be so difficult to go there.”

“What if it wasn’t difficult? Think about that! If the way to Ratenburg was easy, that perfect city would be overrun with rats. Everyone would go there! Because the way is difficult, only the strong and intelligent—like us—can survive the journey.”

My dear wife still looked worried. “I hope you’re right.”

“I know I’m right. Look, my dear, look at my whiskers! Are they twitching? No! That means we’ll get safely across the lake.”

“It might mean that we’ll find a safe nest in the town,” she said, and I realised she was deeply disturbed. This morning she believed she had lost me and Alpha at a foreign railway station. Then her gentle Beta had been almost eaten by a giant eel. It was all too much for a motherly rat who’d been born at the back of a first-class Greek restaurant. I licked behind her left ear. “Don’t worry, my love. Think of our family star. We’ll be safely guided.”

When Alpha came back, she seemed very excited. “I’ve found a boat!”

“What kind of boat?” Retsina asked.

“Where?” I said.

Alpha answered both questions. “It’s a humming-bean cooking pot. Come! I’ll show you!”

Retsina stayed with the other three while I followed Alpha to the space between the two houses with wheels. Under the cloth-skin line was a fireplace, and nearby on a shelf was a large pot and cooking tools. Alpha pointed to the pot. “No eel will bite that!”

I considered it: a strong metal pot with a handle on each side. Certainly it would contain a family of six. But there was a problem. “How will we propel it across the lake?”

“With oars!” said Alpha, indicating two cooking tools: a wooden spoon and a long-handled food scraper. She stood on her hind paws to touch a handle on the pot. “The oars can fit through these loops.”

I was pleased that she had done so well. “My clever ratlet!” I cried.

When we told Retsina, she was still anxious. “How will we get it to the water?”

“That’s what family is for,” Alpha replied.

It did take all of us to push the pot down the slope to the water’s edge, and the closer we got, the more cautious we became. Poor Beta was terrified. But no eel came into the shallows to investigate. I suspect that a metal saucepan was less attractive than a plump little rat.

All the while, the terrible terrier was barking its anger with a madness that had it straining at the end of the rope. We took no notice but kept well out of its reach when we went back for the tools that would be our oars. I dragged one and Retsina dragged the other. Now we had a boat sitting on the edge of the water, two oars in place, but how would we launch it? I suggested we get the ratlets on board first. That was a simple matter. Each climbed up my back and over the top of the pot. Their weight inside it, however, anchored it firmly in the mud. I looked beyond it, checking the surface of the lake for threatening ripples. All was calm. The only threats came from the dog dancing at the end of its tether and telling us what it would do with us.

“Push!” I said to Retsina.

We both pushed as hard as we could. The pot moved a little but was still aground.

“Another push!” I said. “One, two, three!” The pot moved a paw space so that it was half in the water.

“Try again!” said Retsina.

We were both so occupied with launching our pot boat that we hadn’t noticed that the dog had stopped barking. It was Alpha who told us why. “Papa! Mama! Hurry! The dog is biting through its rope.”

I glanced back. It was true. The terrier was chewing the tether that kept us safe. “Push!” I yelled at Retsina.

How we strained against the pot! It was stubbornly slow but each push was a little easier, as the water took some of the pot’s weight.

“Hurry, Papa!” Alpha screamed.

One more heave and the pot bobbed a little. I knew that when Retsina and I got on board, it would go aground again. We needed to take it out further, but that risked us becoming eel bait.

“The dog’s loose! It’s coming!”

We waded deeper, steering the pot out, then I helped Retsina up the side. She tumbled over and reached for my paw. Meanwhile, Alpha and Gamma had taken an oar each. Barking furiously, the dog raced down the beach, but by the time it got to the water’s edge, our pot was bobbing nicely and moving with strokes of the cooking tools. Retsina and I took control of the oars because we were stronger and taller on our hind legs. We were now too deep for wading, and the angry dog was yelling insults from the rim of water. “I’ll get you! I’ll bite out your eyes! I’ll bite off your tails!”

I laughed. “Do your worst, you stupid mongrel!”

I should not have taunted it. In the heat of the moment, I had forgotten that dogs are good swimmers. The terrier made a determined leap into the water and came after us with strong, sure strokes. Its paws were much faster than our makeshift oars.

“Go back!” I yelled at it. “Come any closer and I’ll hit you with this paddle!”

My threat was feeble and the dog knew it. Although it was not a big dog, it was certainly bigger than a family of rats. It would tip the pot over and we’d all find ourselves in the stomachs of hungry eels.

Now the terrier was almost upon us. Its paws paddled fast and it grinned up at me, certain of victory. I looked at the sharp teeth embedded in that smile. Then I observed a disturbance in the water behind the dog’s short tail. The dog’s expression suddenly changed. It turned its head, but before it could yelp, it went under the water and disappeared.

Our pot rocked slightly in small waves and then became steady again, as though nothing had happened. Only Beta cried for the dog. I may have mentioned that Beta is very tender-hearted. The rest of us were too relieved to feel any sympathy for a terrier taken by a giant eel. I glanced over Retsina’s shoulder and saw we were nearly at the opposite shore. It was indeed a narrow lake.

“You were right,” Retsina said to me.

“Right?” I looked at her. “About what?”

“Everything!” She smiled. “We were safe. Your whiskers didn’t twitch once.”