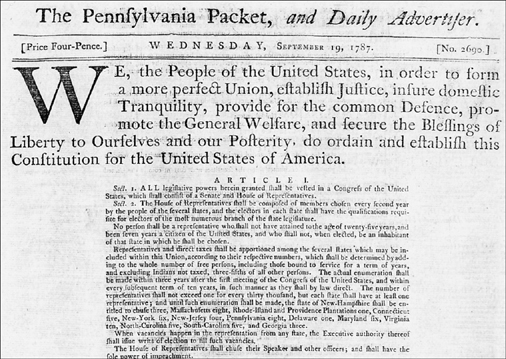

THE PENNSYLVANIA PACKET, AND DAILY ADVERTISER (SEPTEMBER 19, 1787).

When, after a summer of closed meetings in Philadelphia, America’s leading statesmen went public with their proposed Constitution on September 17, 1787, newspapers rushed to print the proposal in its entirety. In several printings, the dramatic words of the Preamble appeared in particularly large type. (Illustration Credit 1.1)

It started with a bang. Ordinary citizens would govern themselves across a continent and over the centuries, under rules that the populace would ratify and could revise. By uniting previously independent states into a vast and indivisible nation, New World republicans would keep Old World monarchs at a distance and thus make democracy work on a scale never before dreamed possible.

With simple words placed in the document’s most prominent location, the Preamble laid the foundation for all that followed. “We the People of the United States, … do ordain and establish this Constitution …”

These words did more than promise popular self-government. They also embodied and enacted it. Like the phrases “I do” in an exchange of wedding vows and “I accept” in a contract, the Preamble’s words actually performed the very thing they described. Thus the Founders’ “Constitution” was not merely a text but a deed—a constituting. We the People do ordain. In the late 1780s, this was the most democratic deed the world had ever seen.

Behind this act of ordainment and establishment stood countless ordinary American voters who gave their consent to the Constitution via specially elected ratifying conventions held in the thirteen states beginning in late 1787. Until these ratifications took place, the Constitution’s words were a mere proposal—the text of a contract yet to be accepted, the script of a wedding still to be performed.

The proposal itself had emerged from a special conclave held in Philadelphia during the summer of 1787. Twelve state governments—all except Rhode Island’s—had tapped several dozen leading public servants and private citizens to meet in Philadelphia and ponder possible revisions of the Articles of Confederation, the interstate compact that Americans had formed during the Revolutionary War. After deliberating behind closed doors for months, the Philadelphia conferees unveiled their joint proposal in mid-September in a document signed by thirty-nine of the continent’s most eminent men, including George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, James Wilson, Roger Sherman, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Gouverneur Morris, John Rutledge, and Nathaniel Gorham. When these notables put their names on the page, they put their reputations on the line.

An enormous task of political persuasion lay ahead. Several of the leaders who had come to Philadelphia had quit the conclave in disgust, and others who had stayed to the end had refused to endorse the final script. Such men—John Lansing, Robert Yates, Luther Martin, John Francis Mercer, Edmund Randolph, George Mason, and Elbridge Gerry—could be expected to oppose ratification and to urge their political allies to do the same. No one could be certain how the American people would ultimately respond to the competing appeals. Prior to 1787, only two states, Massachusetts and New Hampshire, had ever brought proposed state constitutions before the people to be voted up or down in some special way. The combined track record from this pair of states was sobering: two successful popular ratifications out of six total attempts.

In the end, the federal Constitution proposed by Washington and company would barely squeak through. By its own terms, the document would go into effect only if ratified by specially elected conventions in at least nine states, and even then only states that said yes would be bound. In late 1787 and early 1788, supporters of the Constitution won relatively easy ratifications in Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Georgia, and Connecticut. Massachusetts joined their ranks in February 1788, saying “we do” only after weeks of debate and by a close vote, 187 to 168. Then came lopsided yes votes in Maryland and South Carolina, bringing the total to eight ratifications, one shy of the mark. Even so, in mid-June 1788, a full nine months after the publication of the Philadelphia proposal, the Constitution was still struggling to be born, and its fate remained uncertain. Organized opposition ran strong in all the places that had yet to say yes, which included three of America’s largest and most influential states. At last, on June 21, tiny New Hampshire became the decisive ninth state by the margin of 57 to 47. A few days later, before news from the North had arrived, Virginia voted her approval, 89 to 79.

All eyes then turned to New York, where Anti-Federalists initially held a commanding lead inside the convention. Without the acquiescence of this key state, could the new Constitution really work as planned? On the other hand, was New York truly willing to say no and go it alone now that her neighbors had agreed to form a new, more perfect union among themselves? In late July, the state ultimately said yes by a vote of 30 to 27. A switch of only a couple of votes would have reversed the outcome. Meanwhile, the last two states, North Carolina and Rhode Island, refused to ratify in 1788. They would ultimately join the new union in late 1789 and mid-1790, respectively—well after George Washington took office as president of the new (eleven!) United States.

Although the ratification votes in the several states did not occur by direct statewide referenda, the various ratifying conventions did aim to represent “the People” in a particularly emphatic way—more directly than ordinary legislatures. Taking their cue from the Preamble’s bold “We the People” language, several states waived standard voting restrictions and allowed a uniquely broad class of citizens to vote for ratification-convention delegates. For instance, New York temporarily set aside its usual property qualifications and, for the first time in its history, invited all free adult male citizens to vote.1 Also, states generally allowed an especially broad group of Americans to serve as ratifying-convention delegates. Among the many states that ordinarily required upper-house lawmakers to meet higher property qualifications than lower-house members, none held convention delegates to the higher standard, and most exempted delegates even from the lower. All told, eight states elected convention delegates under special rules that were more populist and less property-focused than normal, and two others followed standing rules that let virtually all taxpaying adult male citizens vote. No state employed special election rules that were more property-based or less populist than normal.2

In the extraordinarily extended and inclusive ratification process envisioned by the Preamble, Americans regularly found themselves discussing the Preamble itself. At Philadelphia, the earliest draft of the Preamble had come from the quill of Pennsylvania’s James Wilson,3 and it was Wilson who took the lead in explaining the Preamble’s principles in a series of early and influential ratification speeches. Pennsylvania Anti-Federalists complained that the Philadelphia notables had overreached in proposing an entirely new Constitution rather than a mere modification of the existing Articles of Confederation. In response, Wilson—America’s leading lawyer and one of only six men to have signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution—stressed the significance of popular ratification. “This Constitution, proposed by [the Philadelphia draftsmen], claims no more than a production of the same nature would claim, flowing from a private pen. It is laid before the citizens of the United States, unfettered by restraint.… By their fiat, it will become of value and authority; without it, it will never receive the character of authenticity and power.”4 James Madison agreed, as he made clear in a mid-January 1788 New York newspaper essay today known as The Federalist No. 40—one of a long series of columns that he wrote in partnership with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay under the shared pen name “Publius.” According to Madison/Publius, the Philadelphia draftsmen had merely “proposed a Constitution which is to be of no more consequence than the paper on which it is written, unless it be stamped with the approbation of those to whom it is addressed. [The proposal] was to be submitted to the people themselves, [and] the disapprobation of this supreme authority would destroy it forever; its approbation blot out antecedent errors and irregularities.” Leading Federalists across the continent reiterated the point in similar language.5

With the word fiat, Wilson gently called to mind the opening lines of Genesis. In the beginning, God said, fiat lux, and—behold!—there was light. So, too, when the American people (Publius’s “supreme authority”) said, “We do ordain and establish,” that very statement would do the deed. “Let there be a Constitution”—and there would be one. As the ultimate sovereign of all had once made man in his own image, so now the temporal sovereign of America, the people themselves, would make a constitution in their own image.6

All this was breathtakingly novel. In 1787, democratic self-government existed almost nowhere on earth. Kings, emperors, czars, princes, sultans, moguls, feudal lords, and tribal chiefs held sway across the globe. Even England featured a limited monarchy and an entrenched aristocracy alongside a House of Commons that rested on a restricted and uneven electoral base. The vaunted English Constitution that American colonists had grown up admiring prior to the struggle for independence was an imprecise hodgepodge of institutions, enactments, cases, usages, maxims, procedures, and principles that had accreted and evolved over many centuries. This Constitution had never been reduced to a single composite writing and voted on by the British people or even by Parliament.

The ancient world had seen small-scale democracies in various Greek city-states and pre-imperial Rome, but none of these had been founded in fully democratic fashion. In the most famous cases, one man—a celebrated lawgiver such as Athens’s Solon or Sparta’s Lycurgus—had unilaterally ordained his countrymen’s constitution. Before the American Revolution, no people had ever explicitly voted on their own written constitution.7

Nor did the Revolution itself immediately inaugurate popular ordainments and establishments. True, the 1776 Declaration of Independence proclaimed the “self-evident” truth that “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just Powers from the Consent of the Governed.” The document went on to assert that “whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of [its legitimate] Ends, it is the Right of the People to alter and abolish it, and to institute new Government.” Yet the Declaration only imperfectly acted out its bold script. Its fifty-six acclaimed signers never put the document to any sort of popular vote.

Between April and July 1776, countless similar declarations issued from assorted towns, counties, parishes, informal assemblies, grand juries, militia units, and legislatures across America.8 By then, however, the colonies were already under military attack, and conditions often made it impossible to achieve inclusive deliberation or scrupulous tabulation. Many patriots saw Crown loyalists in their midst not as fellow citizens free to vote their honest judgment with impunity, but rather as traitors deserving tar and feathers, or worse. (Virtually no arch-loyalist went on to become a particularly noteworthy political leader in independent America. By contrast, many who would vigorously oppose the Constitution in 1787–88—such as Maryland’s Samuel Chase and Luther Martin, Virginia’s Patrick Henry and James Monroe, and New York’s George Clinton and John Lansing—moved on to illustrious post-ratification careers.)9

Shortly before and after the Declaration of Independence, new state governments began to take shape, filling the void created by the ouster of George III. None of the state constitutions ordained in the first months of the Revolution was voted on by the electorate or by a specially elected ratifying convention of the people. In many states, sitting legislatures or closely analogous Revolutionary entities declared themselves solons and promulgated or revised constitutions on their own authority, sometimes without even waiting for new elections that might have given their constituents more say in the matter, or at least advance notice of their specific constitutional intentions.10

In late 1777, patriot leaders in the Continental Congress proposed a set of Articles of Confederation to govern relations among the thirteen states. This document was then sent out to be ratified by the thirteen state legislatures, none of which asked the citizens themselves to vote in any special way on the matter.

Things began to change as the Revolution wore on. In 1780, Massachusetts enacted a new state constitution that had come directly before the voters assembled in their respective townships and won their approval. In 1784, New Hampshire did the same. These local dress rehearsals (for so they seem in retrospect) set the stage for the Preamble’s great act of continental popular sovereignty in the late 1780s.11

As Benjamin Franklin and other Americans had achieved famous advances in the natural sciences—in Franklin’s case, the invention of bifocals, the lightning rod, and the Franklin stove—so with the Constitution America could boast a breakthrough in political science. Never before had so many ordinary people been invited to deliberate and vote on the supreme law under which they and their posterity would be governed. James Wilson fairly burst with pride in an oration delivered in Philadelphia to some twenty thousand merrymakers gathered for a grand parade on July 4, 1788. By that date, enough Americans had said “We do” so as to guarantee that the Constitution would go into effect (at least in ten states—the document was still pending in the other three). The “spectacle, which we are assembled to celebrate,” Wilson declared, was “the most dignified one that has yet appeared on our globe,” namely, a

people free and enlightened, establishing and ratifying a system of government, which they have previously considered, examined, and approved! …

… You have heard of Sparta, of Athens, and of Rome; you have heard of their admired constitutions, and of their high-prized freedom.… But did they, in all their pomp and pride of liberty, ever furnish, to the astonished world, an exhibition similar to that which we now contemplate? Were their constitutions framed by those, who were appointed for that purpose, by the people? After they were framed, were they submitted to the consideration of the people? Had the people an opportunity of expressing their sentiments concerning them? Were they to stand or fall by the people’s approving or rejecting vote?12

The great deed was done. The people had taken center stage and enacted their own supreme law.

FROM ANOTHER ANGLE, the drama was just beginning. Preamble-style popular sovereignty was an ongoing principle. No liberty was more central than the people’s liberty to govern themselves under rules of their own choice;13 and the Preamble promised to secure this and other “Blessings of Liberty” not just to the Founding generation, but also, emphatically, to “our Posterity.”

As Wilson explained in Pennsylvania’s ratification debates, the people’s right to “ordain and establish” logically implied their equal right “to repeal and annul.” The people “retain the right of recalling what they part with.… WE [the people] reserve the right to do what we please.” Leading Federalists in sister states echoed this exposition. North Carolina’s James Iredell, who would one day sit on the Supreme Court alongside Wilson, reminded his listeners that in America “our governments have been clearly created by the people themselves. The same authority that created can destroy; and the people may undoubtedly change the government.” Not content to leave the matter implicit, Virginia ratified the Constitution on the express understanding that “the powers granted under the Constitution, being derived from the people of the United States, may be resumed by them, whensoever the same shall be perverted to their injury or oppression.”14

Similar ideas surfaced in New York. Writing as Publius in The Federalist No. 84, Alexander Hamilton explained that “here, in strictness, the people … retain everything [and] have no need of particular reservations. ‘WE THE PEOPLE …, to secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution.…’ Here is a [clear] recognition of popular rights.” By “popular rights” Publius meant rights of the people qua sovereign, including their right to revise what they had created. Following Virginia’s lead, New York used its ratification instrument to underscore its understanding of the Preamble’s principles: “All power is originally vested in, and consequently derived from, the people.… The powers of government may be reassumed by the people whensoever it shall become necessary to their happiness.”15

These assorted speeches, essays, and ratification texts emphasizing the “popular rights” that “the people” “retain” and “reserve” and may “resume” and “reassume” exemplified what the First Congress had centrally in mind in 1789 when it proposed certain amendments as part of a general bill of rights. With its last three words proudly paralleling the Preamble’s first three, the sentence that eventually became the Ninth Amendment declared rights implicitly “retained by the people,” such as their right to alter what they had ordained. Similarly, the Tenth Amendment declared powers “reserved … to the people,” and the First Amendment guaranteed “the right of the people peaceably to assemble” in constitutional conventions and elsewhere. In all these places, the phrase “the people” gestured back to the Constitution’s first and most prominent use of these words in the Preamble.16

In the First Congress, lawmakers pointed not just to the Preamble’s words but also to its more immediate “practical” effect concerning the right to amend.17 By ordaining the federal Constitution, Americans had in practice altered their state constitutions and abolished the Articles of Confederation. For example, most state constitutions in place before 1787 had given state legislatures power to issue paper money and emit bills of credit.18 The federal Constitution abrogated these and other powers by fastening a new regulatory framework upon state governments.19 In deed as well as word, the Preamble stood for ongoing popular sovereignty—the people’s right to change their mind as events unfolded.

Even more dramatically, the Preamble by its very deed implicitly affirmed that the people’s right to amend ultimately required only a simple majority vote, at least within a state. In Massachusetts, a two-thirds vote of the electorate had been required to launch the 1780 state constitution; and the document had provided for an amendment process to begin in 1795 if endorsed by “two-thirds of the qualified voters … who shall assemble and vote.” Yet the federal Constitution drafted at Philadelphia proposed to modify this state constitution well before 1795, and to do so by a mere majority of a specially elected Massachusetts convention, which in the end voted 187 to 168 for the new legal order—far short of two-thirds, and not by a direct tally of all the qualified voters. Even so, once this vote occurred, Massachusetts Anti-Federalists immediately acquiesced, acknowledging that the people had truly spoken, albeit not in the precise manner that had been set out in 1780. In essence, Bay Staters in 1788 reconceptualized their earlier amendment clause as merely one way, rather than the only way, by which the sovereign people might alter their government.20 Ratification of the federal Constitution broke similar new ground in several of Massachusetts’s sister states, where analogous state constitutional issues arose.

Preamble-style ratification also broke new ground by establishing that the people’s right to alter government did not require proof of past tyranny. When the Declaration of Independence trumpeted “the Right of the People to alter or abolish” governments, it had limited this right (as had the influential English philosopher John Locke)21 to situations in which governments had grossly abused their powers—“whenever any Form of Government bec[ame] destructive” of its legitimate ends. The longest section of the Declaration aimed precisely to detail the insufferable “Evils,” the “long Train of Abuses and Usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinc[ing] a design to reduce [Americans] under absolute Despotism.” Such a clear pattern of “repeated Injuries and Usurpations, all having in direct Object the Establishment of an absolute Tyranny” justified a people in exercising their right to change government, even if the consequence would be all-out war against the king.

By the late 1780s, Americans had toppled the old order of George III, and the right to alter could now operate far more freely. Unlike the Declaration, the Constitution did not purport to show—because it did not need to show—that the regime it was amending was tyrannical. The people could properly amend whenever they deemed the status quo outdated or imperfect. If reformers proposed a change, ballots rather than bullets would decide the contest. In contrast to Old World monarchs, New World public servants would accept the people’s constitutional verdict without waging war on them.

Americans understood this transformation even as they were doing the transforming and marveling at their own handiwork. “The people may change the constitutions whenever and however they please,” explained Wilson. “It is a power paramount to every constitution, inalienable in its nature.”22 By their very act of assembling in ratifying conventions to debate the Philadelphia plan, the people were making these words flesh. “Under the practical influence of this great truth, we are now sitting and deliberating, and under its operation, we can sit as calmly and deliberate as coolly, in order to change a constitution, as a legislature can sit and deliberate under the power of a constitution, in order to alter or amend a law.”23

Outside Pennsylvania, other Federalists followed Wilson’s cue. North Carolina’s Iredell contrasted “other countries,” where the people could rightfully change their government only if the king either consented or acted tyrannically (and thus forfeited his right to rule), with America, where “the people may undoubtedly change the government, not because it is ill exercised, but because they conceive another form will be more conducive to their welfare.” In New York, Publius likewise pushed beyond the Declaration in championing “the right of the people to alter or abolish the established Constitution, whenever they find it inconsistent with their happiness.”24

In going a step beyond the Declaration, the Preamble also went several steps beyond ancient republics and the British constitution. In seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England, constitutional reformers often claimed, with varying degrees of accuracy and sincerity, that they were merely restoring good old rules unearthed from a hallowed past rather than minting entirely new rules for a modern era. Shrouding their founding moments in myth and superstition, ancient Greek republics had been even less open to progressive alteration. Solon had stipulated that his constitution for Athens could not be amended for a hundred years, and Lycurgus had contrived to render his Spartan constitution wholly unamendable.25 Contrasting the Preamble with these models from antiquity, Madison/Publius in The Federalist No. 38 took pride in the remarkable “improvement made by America on the ancient [Greek] mode of preparing and establishing regular plans of government.”26

AMERICA’S FOUNDING GAVE the world more democracy than the planet had thus far witnessed. Yet many modern Americans, both lawyers and laity, have missed this basic fact. Some mock the Founding Fathers as rich white men who staged a reactionary coup, while others laud the framers as dedicated traditionalists rather than democratic revolutionaries. A prominent modern canard is that the very word “democracy” was anathema to the Founding generation.27 When today’s scholars quote the framers on how America’s Constitution broke with ancient Greek practices, the standard quotation comes not from Wilson’s July 4 oration or Madison’s similar Federalist No. 38, but rather from a passage in Madison’s Federalist No. 63 that is brandished to prove that the framers were less democratic than the ancients, and proudly so: “The true distinction between [ancient democracies] and the American governments, lies in the total exclusion of the people, in their collective capacity, from any share in the latter.… The distinction … must be admitted to leave a most advantageous superiority in favor of the United States.”

This conventional account misreads both Madison and the Constitution. True, Madison did harbor strong anxieties about the ability of a large mass of people to meet together to legislate. In another unfavorable comment on Greek-style democracy, he observed in The Federalist No. 55 that in “all very numerous assemblies, of whatever character[s] composed, passion never fails to wrest the sceptre from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob.” However, Madison was not an antidemocrat scoffing at the limited capacities of ordinary folk, but rather a republican proceduralist pondering how best to structure lawmaking institutions. Even if every citizen were a philosopher king, how could a legislature function if composed of “six or seven thousand” (Madison’s hypothetical) all clamoring to be heard?

In his view, thousands of people could not have immediately and equally participated in the countless specific decisions implicated in drafting a proposed Constitution in Philadelphia, clause by clause. On the other hand, the issue of ratifying a completed, 4,500-word proposal was a simpler one more fit for democratic judgment. Should the document be approved, yes or no? Thus Madison and the other Philadelphia drafters proposed that their handiwork come before the American people, organized in specially elected statewide conventions. These conventions would be deliberative forums facilitating extended democratic discussion. Largescale direct referenda would have prevented the ultimate ratification votes from benefiting from detailed presentation of competing arguments on issues large and small. In each state, the convention debate process might properly take several weeks. Would it be fair to ask every voter in America to drop everything for so long a period? Wouldn’t it make more sense to ask ordinary voters to read the document on their own, discuss it with friends, and then deputize persons they most trusted to think like themselves to attend a special convention on their behalf? Such specially deputized delegates could then act as ordinary voters themselves would have done had they been present to hear all the extended analysis pro and con.

Nevertheless, the decision to ratify the Constitution via conventions rather than by direct popular votes did risk introducing distortions into the Founding process. Convention delegates might be systematically malapportioned, giving some regions within a state far more than their fair share of influence; delegates might betray the explicit or implicit instructions of ordinary voters; and so on. We shall revisit these possible distortions later in our story, after we have had occasion to examine more general issues of apportionment and representation in Revolutionary America. For now, let us simply note that conventions offered the promise of democratic deliberation that direct statewide popular votes would have lacked.

Similarly, as Madison and other Federalists saw the matter, judicial decisions should not occur via mass society-wide votes of guilty or innocent, liable or not liable, and in this sense The Federalist No. 63 correctly observed that the Constitution excluded the people “in their collective capacity” from day-to-day judicial governance in America. Yet clusters of ordinary citizens—juries—would indeed make crucial decisions after hearing presentations from different sides. Though far smaller than Greek juries (some five hundred jurors had sat in judgment of Socrates), American grand juries, criminal petit juries, and civil juries would enable ordinary Americans to participate directly and daily in American government.

In fact, the Constitution infused some form of democracy into each of its seven main Articles. Echoing the Preamble’s first three words, Article I promised that all members of the new House of Representatives would be elected directly “by the People.” No constitutional property qualifications would limit eligibility to vote for or serve in Congress; nor could Congress add any qualifications by statute. Also, Article I prohibited both state and federal governments from creating hereditary government positions via titles of nobility. Under Articles II and III, the presidency and federal judgeships would be open to men of merit regardless of wealth or lineage. Government servants in all three branches would receive government salaries, lest the right to hold office or public trust be restricted to the independently wealthy. Military hierarchies would answer to democratically elected leaders, not vice versa. Juries of ordinary people would counterbalance professional judges in the judicial branch, as militias of ordinary people would check professional armies in the executive branch. Article IV guaranteed every state a “Republican Form of Government”—that is, a government ultimately derived from the people, as opposed to an aristocracy or monarchy. (The word “republican” came from the same etymological roots—publica, poplicus—as the pivotal Preamble word “people,” whose Greek counterpart, demos, in turn underlay the word “democracy.”) If ordinary legislatures clogged necessary reforms, Article V enabled Americans to bypass these legislatures with specially elected conventions to propose and ratify new constitutional rules. Article VI banned Old World religious hierarchies from formally entrenching themselves in the federal government or excluding adherents of competitor religions from federal service. Finally, Article VII specified how the Preamble’s ordainment and establishment would take place.

The Federalist reflected these populist themes from start to finish. The first paragraph of Publius’s first essay reminded ordinary citizens that “you are called upon to deliberate on a new Constitution” and by an “election” set a new example in world history. The last paragraph of his last essay reiterated the point. “The establishment of a Constitution, in time of profound peace, by the voluntary consent of a whole people, is a prodigy.” Between these bookend paragraphs, Publius repeatedly extolled and elaborated the Preamble’s enactment of popular sovereignty.28 Indeed, in The Federalist No. 39, Madison/Publius wrote that the “first question” to be asked about the Constitution as a whole was whether “the government be strictly republican”—essentially, “a government which derives all its powers directly or indirectly from the great body of the people,” as opposed to an aristocracy or monarchy. Why was this the first question? Because “no other form would be reconcilable with the genius of the people of America [and] the fundamental principles of the Revolution.” Throughout the rest of The Federalist, Publius linked this idea of republicanism to the Constitution’s defining characteristics—its extensive geographic and demographic reach; the interior design of each of its three main branches; its limits on state governments; and so on.29 Similarly, in both his opening and concluding speeches before the Pennsylvania ratifying convention, Wilson pronounced the Constitution “purely democratical,” and in yet another speech he boasted that “the DEMOCRATIC principle is carried into every part of the government.”30

Although some modern readers have tried to stress property protection rather than popular sovereignty as the Constitution’s bedrock idea, the words “private property” did not appear in the Preamble, or anywhere in the document for that matter. The word “property” itself surfaced only once, and this in an Article IV clause referring to government property. Above and beyond the Constitution’s plain text, its clear commitment to people over property shone through in its direct act: As we have seen, the Founders generally set aside ordinary property qualifications in administering the special elections for ratification-convention delegates.

The Founders’ decisions to waive these property rules in the special elections of 1787–88 built upon conceptual and practical foundations laid by several states when framing their state constitutions. In 1776, Pennsylvania militiamen who were unable to meet the property threshold for electing colonial legislators nevertheless voted for delegates to a special constitutional convention, which then drafted and promulgated (without any ratifying vote by the electorate) a remarkably democratic state constitution. By historian Pauline Maier’s estimate, Pennsylvania’s “constitutional convention [was] chosen under rules that expanded the electorate by as much as 50 to 90 percent.” Several years later, the framing and ratification of the Massachusetts Constitution featured even more direct participation by otherwise ineligible propertyless men. In essence, the Massachusetts experience drove a wedge between property qualifications for ordinary legislative elections—qualifications that the document raised compared to colonial rules still in operation in the late 1770s—and property qualifications for adopting the new constitution itself, qualifications that the new constitution eliminated altogether. Thus, the very document adding new property qualifications for ordinary elections was framed by a convention elected by all adult freemen regardless of property, and was then directly submitted to these freemen for ratification. (All freemen were also eligible to serve as delegates at the convention that drafted the proposed constitution.) Constitutional elections, the Massachusetts experience seemed to suggest, were different from ordinary elections and should rest on the broadest popular foundation. In neighboring New Hampshire, the state constitution of 1784 and its three previous unsuccessful incarnations were submitted to an expansive electorate that included all taxpaying New Hampshiremen—an electorate the state legislature in its implementing legislation referred to as “the People” with a capital P.31

Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire were the three states whose constitution-ordaining procedures, going well beyond simple promulgation by the sitting legislature or its equivalent, most closely foreshadowed what the Preamble would call for at the federal level in 1787.32 At Philadelphia, Massachusetts’s Nathaniel Gorham explicitly drew upon his state’s experience when he declared that “many of the ablest men are excluded from the [state] Legislatures, but may be elected into a Convention.” For example, men “of the Clergy” were formally barred from serving in most state legislatures and elsewhere could not serve unless they owned real estate in their own names. Yet Gorham believed that such ordinarily ineligible men had proved “valuable in the formation & establishment” of the Massachusetts Constitution, and that the federal Constitution should likewise be ordained by conventions that would waive ordinary eligibility rules. Fellow Bay Stater Rufus King agreed, and predicted that such conventions would “draw[] forth the best men in the States.” Along with the inclusive ordainment experiences in Pennsylvania and New Hampshire, the high-profile Massachusetts precedent thus pointed those who drafted and implemented the Preamble toward the widest imaginable participation rules for the continental ordainment process.33

THE WIDEST RULES imaginable in the eighteenth century, of course. From a twenty-first-century perspective, the idea that the Constitution was truly established by “the People” might seem a bad joke. What about slaves and freeborn women?

The question is particularly pointed in modern America because it reflects more than some purely subjective or theoretical definition of democracy. Rather, the sensibility underlying the question is itself a constitutional sensibility, informed by the very vision of democracy embodied in the United States Constitution. The Constitution as amended, that is. Later generations of the American people have surged through the Preamble’s portal and widened its gate. Like constitutions, amendments are not just words but deeds—flesh-and-blood struggles to redeem America’s promise while making amends for some of the sins of our fathers.

In both word and deed, America’s amendments have included many of the groups initially excluded at the Founding. In the wake of the Civil War, We the People abolished slavery in the Thirteenth Amendment, promised equal citizenship to all Americans in the Fourteenth Amendment, and extended the vote to black men in the Fifteenth Amendment. A half-century later, We guaranteed the right of woman suffrage in the Nineteenth Amendment, and during a still later civil-rights movement, We freed the federal election process from poll taxes and secured the vote for young adults in the Twenty-fourth and Twenty-sixth Amendments, respectively. No amendment has ever cut back on prior voting rights or rights of equal inclusion. (If this be Whiggism, Americans should make the most of it.)

Previously excluded groups have played leading roles in the amendment process itself, even as amendments have promised these groups additional political rights. Black voters, already enfranchised in many states, propelled the federal Fifteenth Amendment forward; women voters helped birth the Nineteenth; and the poor and the young spearheaded movements to secure their own constitutionally protected suffrage. Through these dramatic acts and texts of amendment, We the People of later eras have breathed new life into the Preamble’s old prose.

WHICH BRINGS US BACK to the Constitution as it looked in the eighteenth century. It’s worth remembering that the Founding generation had fought a revolution against one of the world’s most powerful monarchies, and that the most staunchly conservative elements of colonial society had fled America during the 1760s and 1770s. True, the act of constitution fell far short of universal suffrage as modern Americans understand the idea, but where had anything close to universal suffrage ever existed prior to 1787? Ancient democracies had excluded women and slaves. In classic republican theory, the rights of collective self-government stood shoulder to shoulder with the responsibilities of collective self-defense.34 As a rule, women did not serve in the military; neither should they vote, the argument went. According to eighteenth-century political theory, their interests in both war and politics would find representation through their fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons. Slaves—widely viewed not as part of “the People” but rather as aliens who in war might be more likely to aid the enemy than to defend the polity—were even more obvious candidates for disenfranchisement.35 Also, in a time of widespread voice voting in public, married women and slaves could hardly have voted their own minds, knowing that their husbands and masters retained broad powers of physical chastisement over them.

It is scarcely surprising, then, that no Revolutionary-era state witnessed expansive woman suffrage (although New Jersey apparently did allow a few propertied widows to vote)36 or that no regime either before or after the Revolution ever gave the vote to slaves (as distinct from ex-slaves). In failing to immediately enfranchise slaves or freeborn women in its own ratification process, the Constitution was not backsliding. It was simply not leaping forward.

And yet … in important ways the document did worsen the plight of those most cruelly denied the blessings of liberty. Slavery was the original sin in the New World garden, and the Constitution did more to feed the serpent than to crush it.

During the 1770s, soaring rhetoric of liberty and earnest debate about the sources of legitimate authority pulled many Americans toward abolition. The world’s first antislavery society was born in Philadelphia in 1775. By 1787, Massachusetts judges and juries, reflecting the evolving practices and norms in their local environment, had effectively outlawed slavery in the Bay State. Elsewhere, systems of gradual emancipation began to emerge, aiming to put slavery on what Lincoln would later call a path of “ultimate extinction.” In 1780, Pennsylvania enacted a law under which all children born to slave mothers after the enactment date would be released from service on their twenty-eighth birthdays. Connecticut and Rhode Island passed similar laws in the early 1780s, and several other Northern states would join the crusade over the next two decades. In 1784, the Confederation Congress came close to prohibiting slavery in Western lands after 1800, and in 1787 it barred slavery in the Northwest Territory. By 1788, the ten most northerly states had effectively banned further importation of African slaves, North Carolina had imposed a tax on slave imports, and even South Carolina had temporarily suspended its participation in this transatlantic traffic.37

In sharp contrast, nothing in the original Constitution aimed to eliminate slavery, even in the long run. No clause in the Constitution declared that “slavery shall cease to exist by July 4, 1876, and Congress shall have power to legislate toward this end.” Although many slave children were the flesh-and-blood offspring of the men who ordained and established the Constitution, the blessings of liberty were hardly secured to this posterity, or to the millions of other slave children yet unborn.

In fact, many of the Constitution’s clauses specially accommodated or actually strengthened slavery, although the word itself appeared nowhere in the document. Article I temporarily barred Congress from using its otherwise plenary power over immigration and international trade to end the importation of African and Caribbean slaves. Not until 1808 would Congress be permitted to stop the inflow of slave ships; even then, Congress would be under no obligation to act. Another clause of Article I, regulating congressional apportionment, gave states perverse incentives to maintain and even expand slavery. If a state freed its slaves and the freedmen then moved away, the state might actually lose House seats; conversely, if it imported or bred more slaves, it could increase its congressional clout. Article II likewise handed slave states extra seats in the electoral college, giving the South a sizable head start in presidential elections. Presidents inclined toward slavery could in turn be expected to nominate proslavery Article III judges. Article IV obliged free states to send fugitive slaves back to slavery, in contravention of background choice-of-law rules and general principles of comity. That Article also imposed no immediate or long-run constitutional restrictions on slaveholding in federal territory. Article V gave the international slave trade temporary immunity from constitutional amendment, in seeming violation of the people’s inalienable right to amend at any time, and came close to handing slave states an absolute veto over all future constitutional modifications under that Article.

In the near term, such compromises made possible a continental union of North and South that provided bountiful benefits to freeborn Americans. But in the long run, the Founders’ failure to put slavery on a path of ultimate extinction would lead to massive military conflict on American soil—the very sort of conflict whose avoidance was, as we shall now see, literally the primary purpose of the Constitution of 1788.

“We the People of the United States …” United how? When? Few questions have cast a longer shadow across American history. Jefferson Davis had one set of answers, Abraham Lincoln another. And the war came.

In word and deed, the Constitution yielded its own answers to these epic questions. The very process by which Americans in thirteen distinct states ordained the Constitution in the late 1780s and early 1790s confirmed that they were not a single indissolubly united people prior to the act of ordainment. But that act, along with key words in the Preamble and companion language later in the document, put all concerned on fair notice: After ordainment, Americans from consenting states would indeed “form a more perfect Union” that prohibited unilateral exit. Thus, the establishment of “this Constitution” was not just the world’s most democratic moment, but also, in a manner of speaking, the world’s largest corporate merger.

To put that merger in context, we must recall how the New World took shape in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. British North America grew up not as one continental legal entity but rather as juridically separate colonies founded over a span of many decades. Each colony had its own unique legal charter or other founding instrument—its proto-constitution—and its own laws, governmental institutions, and customary usages. The precise location of the geographic and jurisdictional lines dividing the provinces sometimes blurred or shifted over the years. Nevertheless, it was clear during the century before 1776 that, say, Massachusetts, Maryland, and Virginia were three quite distinct political societies—tied to a common Crown, but as legally separate from one another as India and Ireland.38

The thirteen colonies that ultimately revolted were not the only British outposts in the new continent. As of 1763, these thirteen were nestled between the British West Indies and Floridas to the south, British Nova Scotia to the northeast, and British Quebec to the northwest. Prior to 1776, it was hardly foreordained that these thirteen, and only these thirteen, would eventually unite to form a single legal entity. To be sure, as children of the same Mother England living in adjoining lands far from their parent country, the British North American provinces had much in common, culturally, ethnically, and geostrategically. In the years following the French and Indian War, England began to pay increasing and often unwanted attention to her American brood, adopting a series of stern measures applicable or potentially applicable to all, and thereby driving many of them closer together in resistance. In 1774, representatives of twelve colonies from New England through the Carolinas met in Philadelphia as part of a Continental Congress, which was structured as a kind of international conclave, with each colonial delegation voting as an equal unit. The Congress ended with a public message to Quebec urging it to send delegates to a second Congress to begin in May 1775, and private letters to the colonies of St. John’s, Nova Scotia, Georgia, East Florida, and West Florida asking them to stand together with the twelve in boycotting British goods.39 None of these invitees came in May, but Georgia showed up later. Ultimately, in July 1776, thirteen colonies declared themselves independent of the British Crown and the British Empire.

But did they remain independent of one another? The Declaration of Independence was issued in the name of “the Representatives of the united States of America, in general Congress,” but exactly how were these long-distinct states “united”? Were they more legally “united” than, say, the modern United Nations? Was the word “united” part of the name of a new indivisible nation, or simply an adjective describing thirteen states, acting in unanimous coordination?

In the pivotal sentence of the famous hand-signed 1776 parchment, the word “united” appeared in lowercase, describing the plural and capitalized noun, “States.”40 In the banner stretching across the top, the various fonts and capitalizations also could be read to suggest an alliance more than an indivisible nation:

The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America

The only place where the Declaration capitalized the adjective so as to make it look like part of a legal name was in a phrase describing “these United Colonies,” but strictly speaking, as British colonies the thirteen had never been united as a distinct continental entity.41 Twice the Declaration proclaimed the thirteen to be “Free and Independent States”—perhaps implying by its plural noun, though never quite stating, that the thirteen were independent even of one another, save as they chose to coordinate their actions.42 When the Connecticut assembly met for its regular session in the fall of 1776, it quoted Congress’s “Free and Independent States” language, resolved to “approve of the Declaration of Independence published by said Congress,” and then further resolved “that this Colony is and of right ought to be a free and independent State.”43

The very act of the declaration, and the structure of the body doing the declaring, seemed to confirm the qualified independence of each state. Each colony in the Congress voted as a unit—the colonies were unanimous in July 1776, but not the individual delegates, whose individual votes were never tallied across different colonies. Each delegation routinely obeyed “instructions” issued by its home colony; and in the formal decision to declare independence, each delegation acted on the specific instruction or authorization of its home regime.44 Unlike the newly emerging state legislatures, each of which claimed a right to bind all within the state, patriot and loyalist alike, the Declaration did not purport to bind any state or colony absent its consent. Quebec, Nova Scotia, and the Floridas, for instance, were left out.

The legislative history behind the Declaration is also suggestive. In mid-May 1776, the Congress styled its most important statement yet not as an “order” or “instruction,” but as a “recommend[ation]” that individual colonies adopt new governments wherever the old Crown-linked regimes had lapsed. Three weeks later, delegates from several colonies remained unwilling to vote for independence and reminded the others that Congress had no right to bind any dissenting province, “the colonies being as yet perfectly independent of each other.” If independence were prematurely agreed to by the others, these unready delegates threatened to “retire”—that is, quit Congress—and warned that “possibly their colonies might secede from the Union.” In response, delegates from colonies eager for immediate independence openly conceded that each colony remained free to stay in the budding alliance or to secede from it.45

Over the next few weeks, however, wavering colonies moved toward independence, and the alliance held firm. Events were rushing forward furiously. American patriots were already locked in armed combat with British regulars, and George III had recently dispatched a massive assault force—some thirty thousand men—to crush all rebellion. In the grim words of the Declaration, the king “is at this Time, transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the Works of Death, Desolation, and Tyranny, already begun.” Practically speaking, once a colony formally declared its independence from the Crown, there could be no going back. Without a sizable cadre of colonies willing to plunge ahead together, military and diplomatic prospects looked bleak. If some colonies strayed too far ahead of the rest politically, the vanguard would become a tempting military target. Indeed, if any foot-dragging colony ultimately sided with Britain, it could provide staging grounds for the king’s soldiers, who would be aided by local loyalists controlling the levers of colonial government.46 Better, then, for each colony to stay in tight formation with the others than to break ranks. Thus, the thirteen colonies took care to synchronize their decisions as they headed uncertainly toward independence. Yet mere synchronization hardly meant that the thirteen necessarily became one indivisible nation in July 1776. (No one thinks that the tight synchronization of the D-Day invasion somehow united Britain, America, and Canada as one indivisible nation in June 1944.)

Clearly, the thirteen states were “united” in unanimously declaring independence and pledging to fight together.47 This unanimity, however, said little about the general legal authority of the Continental Congress in any future situation in which the newly independent states might strongly disagree among themselves, or where one or more states might seek to leave the alliance after independence had been won. Nor did the Declaration’s text commit the thirteen states to anything other than independence. Fairly construed, the Declaration and other decisions made in Congress did call upon the thirteen to hang together during the campaign for independence. Beyond this, much of the future relationship among the states—or put differently, between the individual states and the continental collectivity—had yet to be hammered out.

For instance, how would future nonunanimous rules be made? By simple majority vote, or something more? Would some issues require more consensus than others? Would each state count equally, or would more populous states have more votes?48 If the latter, would slaves count, and if so, how much? How would the burdens of raising men and materiel be allocated among the several states? By what procedures would disputes between states be resolved? If a state found itself unhappy with its partners after independence had been won, under what conditions, if any, could it withdraw from its sister states and go its own way?

WELL BEFORE IT ADOPTED the Declaration, the Continental Congress understood that such questions had to be addressed in some future legal instrument that each new state would need to ratify. On June 7, 1776, when Richard Henry Lee, seconded by John Adams, famously moved the magic words “Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States,” he concluded his motion with a proposal “that a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective Colonies for their consideration and approbation.” Four days later—weeks before it finally approved the Lee-Adams independence language—the Congress voted to appoint a committee “to prepare and digest the form of a confederation to be entered into between these colonies.”49

When such a plan ultimately emerged from the post-independence Congress, it underscored in word and deed the sovereignty of each individual state. The opening passages of the Articles of Confederation variously described the arrangement among the states as a “confederacy,” a “confederation,” and a “firm league of friendship with each other” in which “each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence.” Legally, the words “confederacy,” “confederation,” and “league” all connoted the same thing: The “United States” would be an alliance, a multilateral treaty of sovereign nation-states.50 Moreover, the word “retains” strongly suggested that each state was already sovereign and had been so since independence. So, too, the words “freedom, and independence” echoed the Lee-Adams motion and Jefferson’s Declaration itself while making it clear, as the earlier language had not, that each state was “free and independent.”51 The 1780 Massachusetts Constitution further reinforced the point in a clause that reworked the language of the Articles: “The people of this commonwealth have the sole and exclusive right of governing themselves, as a free, sovereign, and independent state.”52 The New Hampshire Constitution of 1784 featured a virtually identical clause.53

The act of confederation confirmed the text of Confederation. The Articles did not formally go into effect until ratified by each and every state. Thus, no state was bound absent its own consent. Historian Jack Rakove has observed that during debates over the drafting of the proposed Articles—debates after the Declaration of Independence—“threats of disunion flowed freely. James Wilson warned that Pennsylvania would never confederate if Virginia clung to its western claims. The Virginia delegates replied that … their constituents would never accept a confederation that required their sacrifice.” South Carolina’s Thomas Lynch, Jr., sternly advised his fellow congressmen on July 30, 1776, that “if it is debated, whether … slaves are [our] property, there is an end of the confederation.”54 If independence in early July had given birth to one indivisible nation rather than thirteen sovereign states working together, how could so many of the Declaration’s signers speak so freely of quitting the union? Why was each state’s consent even necessary to formally activate the Articles?

The Articles further provided that any subsequent amendment would require the states’ unanimous approval—the hallmark of a multilateral treaty regime based on the sovereignty of each state, as opposed to a national regime founded on a truly national people. If the people retained an inalienable right to amend, why should an overwhelming majority of Americans be thwarted simply because a single state—perhaps a tiny one—refused?55 The obvious answer was that both before and after ratifying the Articles, the people of each state—and not the people of America as a whole—were sovereign. A state populace would no more be bound by confederate amendments agreed to in sister states than it would be obliged to obey laws enacted in Geneva or Amsterdam. As Philadelphia delegate William Paterson (who would one day serve on the U.S. Supreme Court) explained these defining traits of the Articles, “This is the nature of all treaties. What is unanimously done, must be unanimously undone.”56

The Confederation’s provisions governing daily relations among the states further reinforced its basic structure as a multilateral treaty. Each state would appoint a delegation of up to seven members, with each delegation casting a single state vote regardless of the delegation’s overall size or the state’s underlying population. Delegates would receive their pay from state governments, which could alter salaries at will to keep delegates in line. State governments also routinely instructed their delegations on how to vote, and retained the right to “recall” and replace their ambassadorial delegates “at any time.”57

Given the clarity of the Confederation’s foundational premise of state sovereignty, its classic international architecture, and its self-description as a “league,” how could so many Americans in ensuing eras—Lincoln most famously—have denied that individual states were sovereign prior to 1787? Partly by mistakenly reading later history back into an earlier period. The Constitution itself set a trap for the unwary by using old legal words in new legal ways without clear warning. Just as the word “Congress” under the Constitution described a different and more powerful institution than did the word “Congress” under the Articles,58 so the phrase “United States” in the Constitution meant something different and much stronger than did the same syllables in the earlier document. It is only a happy coincidence that the same thirteen “United States” from the Declaration and the Articles became the first thirteen “United States” in the Constitution. We must remember that when George Washington took office, North Carolina and Rhode Island were not part of the “United States” as the Constitution used the term. Thus the Preamble spoke precisely of its purpose to “form” a new—more perfect—union rather than simply “continue” or “improve” the old union.

Further confusion about the pre-1787 location of sovereignty has arisen because later readers have often misunderstood what sovereignty did and did not mean to late-eighteenth-century American lawyers. Sovereign states under traditional legal principles were free to enter multilateral treaties, leagues, federations, and confederations without surrendering their ultimate sovereignty. In the words of Swiss jurist Emmerich de Vattel, whose Law of Nations was widely read and cited in Revolutionary America, “Several sovereign and independent states may unite themselves together by a perpetual confederacy, without each in particular ceasing to be a perfect state. They will form together a federal republic: the deliberations in common will offer no violence to the sovereignty of each member.” In his influential Second Treatise, Locke had offered a similar account of the ongoing sovereignty of governments merely “in league” with one another, who had not combined “to make one body politic.” William Blackstone’s Commentaries also affirmed the continuing sovereignty of nation-states that merely joined together in “foederate alliance.”59 Hence, the mere fact that each of the thirteen states agreed to what the Articles called a “perpetual” “union” in no way negated each state’s continuing sovereign status.

Nor was each state’s ultimate legal sovereignty undermined by the fact that Congress—basing its authority initially on the Declaration and de facto alliance and later on the formal Articles—acted and spoke on behalf of the individual states in diplomatic dealings with foreign powers.60 Classic leagues of sovereign states, such as the eighteenth-century Dutch and Swiss confederacies, often coordinated the military and diplomatic affairs of the individual member states. Vis-à-vis the rest of the world, the thirteen American states could act as a unit, so long as their league held together and each state consented to be represented by Congress. Yet this apparent external unity while the Confederation continued intact said little about whether and how a formally “sovereign” state might one day lawfully exit the league.61

What, then, did each state’s ultimate “sovereignty” mean, and how was a “confederation” or “league” any different than a single sovereign nation-state? Within the interior of daily arrangements, a very strong confederacy might well approximate a decentralized nation-state. A confederacy might give important powers, including all powers over foreign affairs, to its common council, while a nation might leave many issues to be decided by local subunits. But at crucial junctures of system creation, amendment, and abolition, the differences could be dramatic. A confederacy essentially rested on the ongoing voluntary participation of its sovereign member states. Each sovereign member of a classic confederacy was free not to join at the moment of creation, typically free to refuse to accede to any later proposed amendment, and ultimately free to leave if, in its good-faith judgment, the core purposes of the confederation were going unfulfilled. Based on the Latin foedus (meaning treaty or covenant) and its cognate fides (faith), a traditional “confederated” union ultimately depended on the good faith and voluntary compliance of member states.62 Thus the precise language of the Articles’ closing clause—in which the delegates of sovereign states agreed to “solemnly plight and engage the faith of our respective constituents”—confirmed the basic structure announced in the document’s opening words.

Alas, plighted faith did not always translate into actual performance. Although on paper the Congress under the Articles enjoyed some important powers, it had no effective means of carrying them out. It could not directly tax individuals or legislate upon them; it had no explicit “legislative” or “governmental” power to make binding “law” enforceable in state courts; it lacked broad authority to set up its own general courts; and it could raise troops and money only by “requisitioning” contributions from each state. On paper, such requisitions were “binding.” In practice, they were mere requests. As one wag put it, Congress “may declare every thing, but do nothing.” By 1787, the Confederation was in shambles. Various states failed to honor requisitions, enacted laws violating duly ratified treaties, waged unauthorized local wars against Indian tribes, and maintained standing armies without congressional permission—all in plain contravention of the Articles.63

America needed a new system. But how to launch it?

THE ANSWER LAY in the Preamble’s matching bookend, Article VII. The Preamble began the proposed Constitution; Article VII ended it. The Preamble said that Americans would “establish this Constitution”; Article VII said how we would “Establish[] this Constitution.” The Preamble said this deed would be done by “the People”; Article VII clarified that the people would act via specially elected “Conventions.” The Preamble invoked the people of “the United States”; Article VII defined what that phrase meant both before and after the act of constitution. The Preamble consisted of a single sentence; so did Article VII. The conspicuous complementarity of these two sentences suggests that they might sensibly have been placed side by side, but the Philadelphia architects preferred instead to erect them at opposite ends of the grand edifice so that both the document’s front portal and rear portico would project the message of popular sovereignty, American style.

According to Article VII, “The Ratification of the Conventions of nine States, shall be sufficient for the Establishment of this Constitution between the States so ratifying the Same.”

The last seven words clinch the case for the sovereignty of each state prior to 1787. The very act of constitution itself began with the premise that each state prior to ratification was free and independent—free to decide for itself whether to “form a more perfect Union” with its sister states or instead go its own way. No state could be bound by the new plan unless it chose that fate for itself; hence Rhode Island and North Carolina found themselves outside the new United States when George Washington took his oath of office on April 30, 1789.

Thus, the text of the Constitution did not say, and the act of constitution did not do, something like the following: “Because the United States is [sic] already one sovereign and indivisible nation, the ratification of nine states shall suffice to establish this Constitution in all thirteen United States.” Instead, the text and act of constitution envisioned a possible dissolution of the old union, with nine or more states going one way while a minority of free and independent sovereign states veered off. In effect, the very act of constitution amounted to a mass secession from the old, confederated united states.

The prospect that some subset of states might secede from the Confederation and reunite under a new Constitution came into view in the opening days of the Philadelphia drafting convention, when Wilson floated the idea that the Constitution could be ratified on the footing of a “partial union, with a door open for the accession of the rest” of the states at some later time. Wilson meant to remind smaller states of the precariousness of their position in the event they were left behind. Small-state men like Paterson were quick to call the bluff. Alluding to “the hint thrown out heretofore by Mr. Wilson of the necessity to which the large States might be reduced of confederating among themselves, by a refusal of the others to concur,” Paterson welcomed them to “unite if they please, but let them remember that they have no authority to compel the others to unite.” Long after the large-state/small-state wrangling had ended, the point of legal principle remained. In Wilson’s words: “As the Constitution stands, the States only which ratify can be bound.”64

But how could such a secession and partial reunion be squared with the Articles of Confederation? The closing section of that document provided that “the Articles of this Confederation shall be inviolably observed by every state, and the union shall be perpetual; nor shall any alteration at any time hereafter be made in any of them; unless such alteration be agreed to in a Congress of the United States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every state.” If the proposed Constitution were an amendment of the Articles (an amendment of the form, “Delete everything thus far and replace it as follows …”), then how could only nine states suffice? Alternatively, if the proposed Constitution were a flat repudiation of the Articles, then how could nine or more ratifying states justify abandoning their supposedly “perpetual” union with the remaining states?65

A strong realpolitik answer was that sovereign states sometimes broke their pledges in order to safeguard their vital interests.66 If repudiation of the Articles would violate the niceties of international law, so be it. The very violation of the Articles implicit in the Constitution’s ratification by a supermajority of nine or more states would only prove that the Confederation was a failed experiment.

A more legalistic answer was that the material breaches of promised state performance under the Articles gave each compacting party—each state—a right to rescind the agreement under general principles of contractual and international law. Blackstone’s influential Commentaries had noted that in the case of a nonconfederate, “incorporate union” such as the 1707 union of England and Scotland (the very kind of more perfect union that, as we shall see, the Constitution would later propose) no rescission option existed: “The two contracting states are totally annihilated [qua sovereign states], without any power of revival; and a third arises from their conjunction, in which all the rights of sovereignty … must necessarily reside.” But in the case of a simple “foederate alliance”—that is, a mere confederation or league of sovereign states—an infringement of fundamental conditions “would certainly rescind the compact.”67

Nor did the language in the Articles of Confederation that “the union shall be perpetual” doom this legal analysis. This language was itself yoked to a mandate that the Articles “shall be inviolably observed by every state.” Under standard principles of international law, each of these yoked mandates was a condition of the other. When inviolable observation lapsed, so did the obligation of perpetual union. Indeed, international law principles helped explain why perpetuity and inviolability were so pointedly paired. As the influential jurist Vattel made clear, “Treaties contain promises that are perfect and reciprocal. If one of the allies fails in his engagements, the other may … disengage himself from his promises, and … break the treaty.”68 Thus, the legalistic argument went, the decisive fact about the Confederation was that it was a self-described league, a multilateral treaty. The word “perpetual” merely specified what kind of league it would be: the firmest of leagues, but a league nonetheless.

When pressed, leading Federalists at times resorted to this legalist defense of the act of constitution as embodied in Article VII. Having privately penned the breached-treaty argument in the months before Philadelphia,69 Madison repeatedly advanced this claim in the closed-door deliberations. “As far as the articles of Union were to be considered as a Treaty only of a particular sort, among the Governments of Independent States,” the writings of various “Expositors of the law of Nations” clearly suggested that “a breach of any one article, by any one party, leaves all the other parties at liberty, to consider the whole [compact] as dissolved.”70 Several months later, Madison/Publius went public with the idea in The Federalist No. 43:

A compact between independent sovereigns, founded on ordinary acts of legislative authority, can pretend to no higher validity than a league or treaty between the parties. It is an established doctrine on the subject of treaties, that all the articles are mutually conditions of each other; that a breach of any one article is a breach of the whole treaty; and that a breach, committed by either of the parties, absolves the others, and authorizes them, if they please, to pronounce the compact violated and void. Should it unhappily be necessary to appeal to these delicate truths for a justification for dispensing with the consent of particular States to a dissolution of the federal pact, will not the complaining parties find it a difficult task to answer the MULTIPLIED and IMPORTANT infractions with which they may be confronted?

Other leading Federalists, including South Carolina’s Charles Cotesworth Pinckney (who had studied law at Oxford under Blackstone himself) and North Carolina’s James Iredell (a future justice), mustered similar public defenses of Article VII in their home states.71

For sound rhetorical reasons, the Federalists tended to whisper this legalistic defense rather than shout it from the rooftops.72 Few friends of the Constitution were as forthright on the issue as Madison/Publius, who himself put the point as softly as possible—calling the question “very delicate,” prefacing his exposition with a capitalized “PERHAPS,” and admitting that he raised the breached-treaty defense “unhappily.” A breached treaty was voidable, not void ab initio. A state had a right to withdraw, but it also had a right to stay and demand full performance. Even if it was legally permissible, was withdrawal wise? What if the Constitution failed to win the assent of nine states? Even a tottering alliance might be better than none, and Madison was not the kind of man to pull down his only shelter, however ramshackle, before fitting up his new abode. Hence his closing comment: “The time has been when it was incumbent on us all to veil the ideas which this paragraph exhibits.”

Conclusively establishing the requisite breaches would have required lots of ugly finger-pointing—hardly the kind of thing conducive to launching a new nation in the spirit of harmony. Any direct references to specific state violations of the Articles risked causing offense to particular persons or states that the Federalists were seeking to woo.73 As a rule, the best Federalist strategy was to blame everything on the tiny, ill-governed, and obstreperous state of Rhode Island, which had first thwarted needed reforms of the Confederation and then boycotted the Philadelphia Convention. Additionally, the precise details of any ultimate breached-treaty defense would depend on which state or states might choose to both reject the Constitution and then complain about the dissolution of the old confederacy, and also on how the new union treated the new outsider(s)—yet another exceptionally delicate set of issues (which Madison explicitly ducked in The Federalist No. 43). The states abandoning the old confederacy would be on firmest ground if the nonratifying complainant itself had ranked among the league’s most flagrant laggards. In the midst of the ratification process, however, no one could know which states, if any, might ultimately refuse to ratify.

This uncertainty was one of the reasons that the Preamble spoke generally of “the United States” rather than listing the thirteen states seriatim, as Wilson had done in his first draft.74 Such a list would have unwisely counted thirteen ratifications by name before any had materialized—and in a section of the document whose special visibility might prove particularly embarrassing if one or more states failed to say yes.

THE PROMINENCE OF THE PREAMBLE also made it a perfect place to renounce the basic structure of the Articles. Although states would enter the Constitution as true sovereigns, they would not remain so after ratification. The formation of a “more perfect Union” would itself end each state’s sovereign status and would prohibit future unilateral secession, in plain contrast to the decidedly less-than-perfect union under the Articles. True, the Preamble did not expressly proclaim that its new, more perfect union would be “perpetual”—and for good reason: Why borrow a word from the Articles of Confederation that did not quite mean what it said in that document, a word that was being thrust aside by the very act of constitution itself? Thus, the Constitution signaled its decisive break with the Articles’ regime of state sovereignty and false federal perpetuity in other ways.

One notable Preamble word marking the metamorphosis was “Constitution.” Not a “league,” however firm; not a “confederacy” or a “confederation”; not a compact among “sovereign” states—all these high-profile and legally freighted words from the Articles were conspicuously absent from the Preamble and every other operative part of the Constitution. The new text proposed a fundamentally different legal framework. Henceforth America would have a written “Constitution” deriving from a continental people, unmistakably styled after earlier state prototypes, like the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. As these state constitutions, exalted texts in confederate America, had exemplified state-based popular sovereignty under the Articles, so now a new United States Constitution—the new supreme law of the land—would shape a new continental nation whose sovereign would be a truly continental people. Lest there be any doubt, later parts of the document precisely defined the status of “this Constitution,” a self-referential phrase that appeared several more times—most importantly in Articles V and VI (the only places where the phrase popped up more than once) and in Article VII, the Preamble’s matching bookend.75