The Puzzle of the Hobbit People

(100,000 to 10,000 BCE)

Flores is part of a chain of Indonesian islands that includes Sumatra and Java. It was there, in Ling Bua cave, in 2004, that a team of archaeologists discovered a female skeleton that they labeled “the Hobbit.” Like J. R. R. Tolkien’s invention, this creature was tiny: when she died about 18,000 years ago at about 30 years old, she had stood only a little higher than 3 feet and weighed about 55 pounds—about the size of a 3-year-old modern human. These tiny creatures, named Homo floresiensis, likely evolved from another early species of human, Homo erectus, which arrived on Flores about 850,000 years ago.

Soon archaeologists had unearthed additional Hobbit bones in Ling Bua cave. These bones confirmed that this early human had a skull the size of a grapefruit. It looked as though its kind might even be the origin of our legends of “little people”—fairies, dwarfs, elves, leprechauns, and the rest.

Homo floresiensis

The Little People

The dates do seem to leave open the possibility that the Hobbit people gave rise to little people folklore. The Hobbit people came to Flores about 100,000 years ago and were around until about 13,000 years ago. Our species, Homo sapiens, has been in Asia and Europe about 40,000 years.

Indonesian folklore describes a creature called Ebu Gogo, which means “meat-eating grandmother.” This race of little, hairy people had potbellies and ears that stuck out. Were the Ebu Gogo really Homo floresiensis?

The people of Flores believe that these creatures existed as recently as 400 years ago—when the first Portuguese traders arrived on the island in their quest for spices. Others contend that the Ebu Gogo were still around a mere 100 years ago. The local population evidently regarded these little people as scavenging nuisances.

Ling Bua cave on the Indonesian island of Flores. This limestone cave has yielded numerous specimens of Homo floresiensis, also known as the Hobbit people.

Did the Flores locals find the Ebu Gogo so annoying that they eventually exterminated them? An October 30, 2004, article in New Scientist magazine included this account of the Ebu Gogo.

The Nage people of central Flores tell how, some 300 years ago, villagers disposed of the Ebu Gogo by tricking them into accepting gifts of palm fiber to make clothes. When the Ebu Gogo took the fiber into their cave, the villagers threw in a firebrand to set it alight. The story goes that all the occupants were killed, except perhaps for one pair, who fled into the deepest forest, and whose descendants may be living there still.

The article also tells us that such tales are common in Indonesia, according to anthropologist Gregory Forth. Folktale abound about the Ebu Gogo kidnapping human children, hoping to learn from them how to cook. The children always easily outwit them.

Skull of Homo floresiensis

Speech and Intelligence

All this raises an interesting question about our human ancestry. How did we humans begin to develop intelligence? The probable answer: when we learned to speak.

In 1997, while exploring an ancient lake bed at Mata Menge, on the island of Flores, a group of paleoanthropologists from the University of New England in New South Wales, Australia, found stone tools. Mike Morwood and his colleagues found the tools in a bed of volcanic ash dated from more than 800,000 years ago, the time of Homo erectus. Animal bones from nearby gave the same date. What was unusual is that Flores is a relatively small island and was not known to be a site of ancient humans. The nearest such site is the far larger island of Java, the home of Java Man, who also belongs to the species Homo erectus.

To reach Flores, these primitive humans would have had to sail from island to island, making crossings of around a dozen miles. This sounds a modest distance, but members of the species Homo erectus are regarded as little more than “glorified chimps,” as Morwood puts it. But if they were able to sail the seas, they must have been rather more than that. Moreover, Morwood argues, the organizing ability required by a fairly large group to cross the sea suggests that Homo erectus possessed some kind of linguistic ability. In other words, ancestors of nearly a million years ago were intelligent enough to collaborate on the building of rafts.

But if the Ebu Gogo of Flores were actually Hobbit people, descendants of those island-hopping Homo erectus, then they have helped us to solve this interesting scientific puzzle, and we can say with confidence that Homo erectus could speak. The description of Ebu Gogo earlier, after mentioning that Ebu Gogo walked awkwardly and had prominent ears, adds: “They . . . often murmured in their own language and could repeat what is said to them in parrot-like fashion.” And if, as the above story tells us, two of them escaped the fire that destroyed their kind, then it is possible that we may yet have a chance to study them and discover whether they had language or could merely parrot responses.

Did the Stone Age French Discover America?

(15,000 to 19,000 BCE)

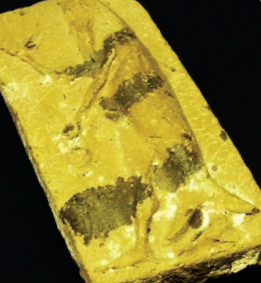

In 1933 a flint spearhead was discovered in a dried-up riverbed near the town of Clovis, New Mexico. The find was remarkable in a number of ways. First, it lay among the bones of a mammoth, having presumably been used to kill the animal. Second, it was beautifully made: double-bladed and double-faced, light and aerodynamic, and intricately flint-knapped—chipped out using sophisticated bone tools. It was also 11,500 years old.

A Clovis spearhead

Clovis People

The Clovis spearhead was the first discovered artifact from the oldest known settlers of the Americas, who are now commonly referred to as the Clovis people. But soon Clovis spearheads—all dating to about 11,500 years ago—were cropping up all over North America.

Based on the geographical spread of the unearthed spearheads and other evidence, scientists concluded that the Clovis people crossed the Bering Strait into northwest North America from Siberia during the last ice age. And it became scientific dogma that the Clovis people were the first human inhabitants of the Americas and the sole ancestors of all modern American Indians.

But were they really the first?

European Settlers?

There is no evidence of Clovis technology in Siberia at the time of the Bering Strait migration, which leads us to ask, where did the skill develop to create such spearheads? The obvious answer is in the Americas, after the migration.

But another people had acquired flint-knapping skills identical to those of the Clovis during the last ice age. These were the Solutrean hunter-gatherers of what is now western France. One of the most highly creative early cultures, the Solutreans invented the eyed needle, made carvings and cave paintings, and used flint-knapping techniques intricate enough to construct stone fishhooks and barbed arrowheads. They also made spearheads almost identical to the Clovis spearheads found in the Americas. But the Solutreans were making their spearheads between 17,000 and 21,000 years ago—at least 5,500 years before the Clovis people. Despite this, there was apparently no intermediate link between the two cultures, until very recently.

During the last 30 years, an archaeological dig at Meadowcroft, Pennsylvania, has started to provide clear evidence of human activity between 16,000 and 19,000 years ago—before the Clovis people migrated to North America. And at another dig in Cactus Hill, Virginia, researchers discovered Clovis/Solutrean–style spearheads dating from about 15,000 to 17,000 years ago.

A bone needle (left) and a bone fishhook (right) from a Solutrean tool kit.

Gone Fishing

Perhaps it was the European Solutreans who were the first to arrive in North America. The theory is controversial because it controverts more than 70 years of scientific orthodoxy: that the Clovis people from Siberia were the first to reach the New World around 12,000 years ago.

How, opponents of the “Solutrean-first” theory ask, did Stone Age hunter-gatherers manage to cross the 3,000, storm-wracked miles of the Atlantic Ocean during an ice age?

During the last ice age the northern hemisphere was covered by solid ice sheets as far south as northern France in Europe and the Great Lakes in North America. But far from being an impediment to the traveling Solutreans, the resulting ice packs in the North Atlantic would have formed easy stepping-stones for canoe-based travel. In fact Inuit tribes living on the modern northern ice sheets regularly traveled in this way up to a few decades ago, camping on ice floes and living on trapped fish and seals.

The Solutrean invention of the eyed needle shows that they were the first people able to make such a journey; sewn leather clothes and boat hulls would have been essential to keep out the freezing water of the Atlantic.

Solutrean First

The “Solutrean-first” theory has met with opposition from American Indians as well as conservative archaeologists. Given what the second wave of post-Columbus European settlers did to American Indians, it is not surprising that many dislike the thought that some of their remotest ancestors might have been European colonizers.

Genetic Footprints

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is part of the human genome, one that mutates at an exact, regular pace. Studying mtDNA mutation markers and comparing differences among population groups allows scientists to reconstruct early human migration. That’s because every human shares mtDNA markers from the early African period of human history, but groups that migrated west and those that migrated east after leaving Africa have different subsequent mtDNA markers. This shows that this is where the human population branched at that time.

Initial studies of mtDNA seemed to back the Solutrean-first theory, indicating a typically European strain in certain groups of northeastern American Indians dating back to between 15,000 to 30,000 years ago. But a subsequent genome study has shown the same strain in modern native Siberians as well. This, opponents of the Solutrean-first theory claim, shows that all American Indians descend from the Siberian/Clovis stock.

In fact, nothing could be further from the case. It is a grim fact that East Coast American Indian tribes were those that came closest to obliteration at the hands of post-Columbus European colonists. If there had been a Solutrean DNA strain in American Indians, it might well have been wiped from the slate of history.

The Cactus Hill and Meadowcroft archaeological sites prove that humans inhabited North America millennia before the influx of the Clovis people from Siberia. The only questions left to be answered are: who were the pre-Clovis Americans and where did they come from?

The Dogon and the Ancient Astronauts: Evidence of Visitors from Outer Space?

(3200 BCE)

The theory that Earth has been visited, perhaps even colonized, by beings from outer space has been a part of popular folklore since the 1968 release of Stanley Kubrick’s cult movie 2001: A Space Odyssey (written by Arthur C. Clarke). But it had already been in the air for many years—in fact, since 1947. That’s when a businessman named Kenneth Arnold was flying his private plane near Mount Rainier in Washington State and reported seeing nine shining disks traveling at an estimated speed of 1,000 miles per hour. Arnold called them “flying saucers.” Soon, sightings of unidentified flying objects (UFOs) were occurring all over the world.

A Dogon wearing a traditional tribal mask

Flying Saucers Everywhere

In 1960 a book appeared in France: The Morning of the Magicians (Le matin des magicians) by Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergier. It became an instant best-seller. It also may claim the dubious credit of having initiated the occult boom of the 1960s. The book included speculations about the Great Pyramid, the statues of Easter Island, Hans Hoerbiger’s theory that the moon is covered with ice (soon to be disproved by the moon landings), and the reality of alchemical transformation. There was also the obligatory section on the famous Piri Reis map (see pages 24–25), in which the authors succeed in confusing the sixteenth-century pirate Piri Reis with a Turkish naval officer who presented a copy of the map to the Library of Congress in 1959. They conclude the discussion of this map with: “Were these copies of still earlier maps? Had they been traced from observations made on board a flying machine or space vessel of some kind? Notes taken by visitors from Beyond?”

The Swiss writer Erich von Daniken developed the “ancient astronaut” theme in a book called Chariots of the Gods? (1963), but an almost willful carelessness about facts finally destroyed his creditability as a serious scholar.

These speculations caused excitement because the world was in the grip of flying-saucer mania. Books by people who claimed to be “contactees” became best-sellers. And though many “sightings” could be dismissed as hysteria—or as what Carl Jung called “projections” (meaning religious delusions)—a few were too well authenticated to fit that simplistic theory.

After an American pilot described the mysterious objects he saw speeding through the sky as “flying saucers,” reports of similar sightings began pouring in from observers around the world.

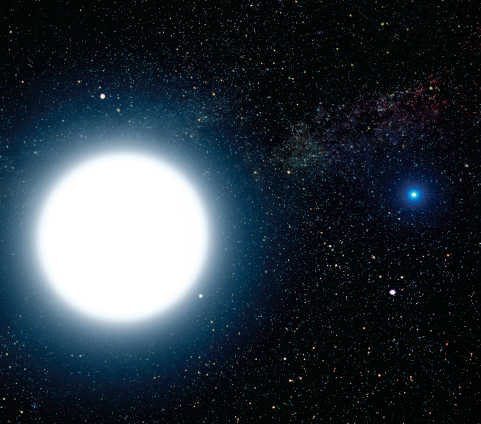

The “ancient astronaut” theorists have at least one extremely powerful piece of evidence on their side. Members of an African tribe called the Dogon, who live some 300 miles south of Timbuktu in the Republic of Mali, possess knowledge of astronomy that some claim was transmitted to them by “spacemen” from the star Sirius A, which lies 8.7 light-years away from Earth. Dogon mythology insists that the “Dog Star” Sirius A (so-called because it is in the constellation Canis) has a dark companion that is dense, very heavy, and invisible to the naked eye. This is correct: Sirius A does indeed have a dark companion, which is known as Sirius B. Changes in Sirius A’s motion led a German astronomer to predict the existence of Sirius B in 1844, and in 1862 an American telescope maker finally observed it—although it was not described in detail until the 1920s. Astronomers concluded that it was a white dwarf star.

An artist’s impression shows the binary star system of Sirius A and its diminutive blue companion, Sirius B. Sirius A, the large, bluish white star at left, appears to overwhelm Sirius B, the small but very hot and blue white-dwarf star on the right.

The Dog Star

Two French anthropologists, Marcel Griaule and Germaine Dieterlen, first revealed the “secret of the Dogon” in an obscure paper in 1950; it was entitled “A Sudanese Sirius System” and was published in the Journal de la Societe des Africainistes.

The two anthropologists had lived among the Dogon since 1931, and in 1946 Griaule was initiated into the religious secrets of the tribe. He was told that fishlike creatures called the Nommo had come to Earth from Sirius A to civilize its people. The Dogon called Sirius B po tolo (naming it after the seed that forms the staple part of their diet, and whose botanical name is Digitaria).

Sirius B is made of matter heavier than any on Earth and moves in an elliptical orbit, taking 50 years to do so. It was not until 1928 that Sir Arthur Eddington postulated the theory of white dwarfs—stars whose atoms have collapsed inward, so that a piece the size of a pea could weigh half a ton.

Griaule and Dieterlen went to live among the Dogon three years later. Is it likely that some traveler carried a new and complex astronomical theory to a remote African tribe—one that had never possessed telescopes—in the three years between 1928 and 1931?

A ground-based image of the constellation Canis Major shows how bright Sirius A, at center, appears in the night sky. Sirius B, however, is invisible to the naked eye.

In the mid-1960s an American scholar named Robert Temple traveled to Paris to study the Dogon with Germaine Dieterlen. He soon concluded that the knowledge shown by the Dogon could not be explained away as coincidence.

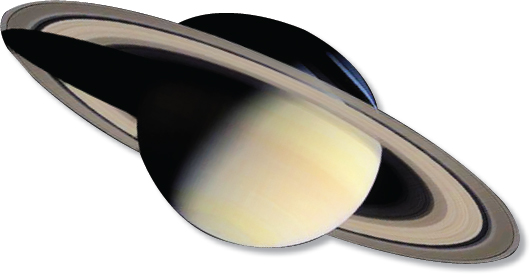

The Dogon appeared to have an extraordinarily detailed knowledge of our solar system. They said that the moon was “dry and dead” and drew Saturn with a ring around it (Saturn’s rings are visible only with the aid of a telescope). The Dogon knew that the planets revolved around the sun. They knew about the moons of Jupiter (first seen through a telescope by Galileo). They had recorded the movements of Venus in their temples. They knew that the earth rotates and that the number of stars is infinite. And when they drew the elliptical orbit of Sirius, they showed the star off center, not in the middle of the orbit—as someone without knowledge of astronomy would naturally conclude.

Saturn, photographed by the Cassini orbiter. Although the Dogon people did not have telescopes when European researchers studied their culture in the 1930s, they knew that Saturn had its distinctive rings.

The Nommo

The Dogon insist the amphibious Nommo brought their knowledge to them from a “star,” which, like Sirius B, rotates around Sirius A and whose weight is only a quarter of Sirius B’s.

The Dogon worshipped the Nommo as gods. They drew diagrams to portray the spinning of the craft in which these creatures landed and were precise about the landing location.

Our telescopes have not revealed the “planet” of the Nommo, but that is hardly surprising. Astronomers discovered Sirius B only because its weight caused perturbations in the orbit of Sirius A. The Dog Star is 35.5 times as bright (and hot) as our sun, so any planet capable of supporting life would have to be in the far reaches of its solar system and would almost certainly be invisible to telescopes. Temple surmises that the planet of the Nommo would be hot and steamy and that this probably explains why intelligent life evolved in its seas, which would be cooler. These fish-people would spend much of their time on land but close to the water; they would need a layer of water on their skins to be comfortable, and if their skins dried, it would be as agonizing as severe sunburn. Temple sees them as a kind of dolphin.

A Dogon village in Mali. The remote, arid land inhabited by the Dogon people seems a surprising place to inspire myths about amphibious creatures like the Nommo.

But what were such creatures as the Nommo doing in the middle of the desert, near Timbuktu? In fact, the idea seemed obviously absurd to Temple. For many reasons, he is inclined to believe that the landing of the Nommo took place in Egypt, not Mali.

Temple also points out that a Babylonian historian named Berossus—a contemporary and apparently an acquaintance of Aristotle (fourth century BCE)—claims in his history, of which only fragments survive, that Babylonian civilization was founded by alien amphibians, the chief of whom is called Oannes—the Philistines knew him as Dagon. The Greek grammarian Apollodorus (about 140 BCE) had apparently read more of Berossus, for he criticizes another Greek writer, Abydenus, for failing to mention that Oannes was only one of the “fish-people”; he calls these aliens “Annedoti” (“repulsive ones”) and says they are “semi-demons” from the sea.

An ancient plaque depicts the Babylonian god Oannes. Greek texts recount how Oannes came out of the sea to teach the Babylonians the arts of civilization. Oannes appeared as half human and half fish, and he spoke in a human voice.

Stars in the Sky

Why should the Dogon pay any particular attention to Sirius A, even though it was one of the brightest stars in the sky? After all, it was merely one among thousands of stars. There, at least, the skeptics can produce a persuasive answer. Presumably the Dogon learned from the Egyptians, and for the ancient Egyptians, Sothis (as they called Sirius A) was the most important star in the heavens—at least, after 3200 BCE, when it began to rise just before the dawn, at the beginning of the Egyptian New Year, and signaled that the Nile was about to rise.

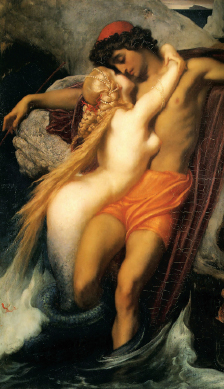

Temple suggests that the ancients may have looked toward the Canis Major constellation for Sirius B and mistaken it for Al Wazn, another star in the constellation. He also suggests that Homer’s Sirens—part mermaidlike, part birdlike creatures who are all-knowing and who try to lure men to their deaths—are actually “Sirians,” amphibious goddesses. He furthermore points out that the famous boat of Greek mythology, Jason’s Argo, is associated with the goddess Isis and that it has 50 rowers—50 being the number of years it takes Sirius B to circle Sirius A. There are many fish-bodied aliens in Greek mythology, including the Telchines of Rhodes, who were supposed to have come from the sea and to have introduced humans to various arts, including metalwork. Significantly, the Telchines had dogs’ heads.

A nineteenth-century illustration of a Siren. Were these mythological water spirits inspired by creatures from Sirius?

Evidence in Africa

Temple published his theories about the Dogon’s source of knowledge in the book The Sirius Mystery in 1976. The Sirius Mystery is full of “evidence” based on his reading of mythology. Critics have attacked his theories as examples of stretching interpretation too far. Yet what remains when all the arguments have been considered is the curious fact that members of a remote African tribe had some precise knowledge of an entire star system not visible to the human eye alone and that they attribute this knowledge to aliens from that star system. That single fact suggests that in spite of von Daniken’s absurdities, we should remain open-minded about the possibility that alien visitors once landed on our planet.

(1922)

On November 26, 1922, the English archaeologist Howard Carter made a fabulous discovery in the Valley of the Kings, near ancient Thebes (modern Luxor). He peered through a small opening above the door of an ancient pharaoh’s tomb, holding a candle in front of him. What he saw dazzled him: “everywhere the glint of gold.” He and Lord Carnarvon had made the greatest find in the history of archaeology. Thrilled, they pressed on with their excavation, undeterred by a clay tablet with the hieroglyphic inscription, DEATH WILL SLAY WITH HIS WINGS WHOEVER DISTURBS THE PEACE OF THE PHARAOH.

Tutankhamun’s mask

Disturbing the Peace

By 1929, 22 people who had been involved in opening the tomb had died prematurely. Other archaeologists dismissed talk about ‘“the curse of the pharaohs” as journalistic sensationalism. Yet it is difficult to imagine that this long series of deaths was merely a frightening coincidence.

Relief of Akhenaten and his wife, Nefertiti, with two of their children. Prominent in the background is the sun. Tutankhamun may have been one of the royal couple’s children.

King Tut

The tomb Carter discovered belonged to Tutankhamun, heir of the “great heretic” Akhenaten. Ruling from about 1353 to 1336 BCE, Akhenaten was the first monotheistic king in history.

Akhenaten abandoned the capital at Thebes, with all its temples to Egypt’s numerous gods, and built himself a new capital, also called Akhenaten (Horizon of Aten), at a place now called Amarna, or Tel el-Amarna. He worshipped only one god, the sun god Aten. His people disliked this new religion and were relieved when Akhenaten died young. (So were the priests.) Tutankhamun, either Akhenaten’s son or son-in-law, was a mere child when he came to the throne, and died from a blow to the head at the age of 18. No one knows the circumstances surrounding his death, only that his skull was cracked. Historically speaking, Tutankhamun is virtually a nonentity, whose short reign deserves little attention. His only achievement was to restore the old religion and move his capital back to Thebes.

At the time of Tutankhamun’s death, Egypt’s high priest was a man called Ay. Ay quickly seized power and married Tutankhamun’s 15-year-old widow, Ankhesenamun. He had reigned for fewer than four years when once again a usurper seized the throne, this time a general named Horemheb. As soon as Horemheb became pharaoh, he set out to erase the memory of Akhenaten and Tutankhamun from history; he had their names chiseled off all hieroglyphic inscriptions and used the stones of the great temple of the sun at Amarna to build three pyramids in Thebes.

Yet he neglected to do the most obvious thing of all: destroy the tomb of Tutankhamun. Why? Horemheb must have had some very persuasive reason for deciding to leave the tomb of his enemy inviolate.

The Play’s the Thing

The first signs of trouble relating to Akhenaten and his progeny—known to the modern world at least—occurred even before Carter opened Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922. In 1909 Joe Linden Smith worked on excavations in the Valley of the Kings. He was married to an attractive 28-year-old woman named Corinna. Among their closest friends were Arthur and Hortense Weigel. One day when they were descending the slope into the Valley of the Queens, Joe Smith and Arthur Weigel came upon a natural amphitheater. They decided to present their own play and invite most of the archaeological community from Luxor. Their aim was not pure entertainment; they intended nothing less than to intercede with the ancient gods to lift an ancient curse that had consigned Akhenaten’s spirit to wander for all eternity.

Smith and Weigel decided to present their play on January 26, 1909, the presumed anniversary of Akhenaten’s death. On January 23 they held their dress rehearsal. In the play, the god Horus appeared and conversed with the wandering spirit of Akhenaten, offering to grant him a wish. Akhenaten asked to see his mother, Queen Tiy. The queen, played by Corinna, was summoned by a magical ceremony. Akhenaten told her that even in his misery he still drew comfort from the thought of the god Aten and asked his mother to recite his hymn to the sun god.

As Corinna began to recite the hymn, the rising wind drowned out her words. Suddenly a violent storm, blowing sand and hailstones, was upon them, forcing a dramatic end to the rehearsal.

Later that evening Corinna complained of a pain in her eyes, and Hortense of cramps in her stomach. That night both had similar dreams; they were in the nearby temple of Amen, standing before the statue of the god. This came to life and struck them with its flail—Corinna in the eyes, Hortense in the stomach. The next day Corinna had to be rushed to a specialist in Cairo, who diagnosed one of the worst cases of trachoma—a debilitating eye disease often resulting in blindness—that he had ever seen. Twenty-four hours later, Hortense joined Corinna in the same nursing home; during the stomach operation that followed, she nearly died. The play had to be abandoned.

The Valley of the Kings is a valley in Luxor, Egypt, where, for nearly 500 years, from the sixteenth to eleventh century BCE, kings, queens, and other nobles had their tombs constructed. It was here that Carter found the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922. Although there are at least 63 tombs and chambers in the valley, Tut’s may be the most famous.

Howard Carter, the man who finally discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb, was born in 1873 and had moved to Egypt as a teenager. Carter became Chief Inspector of Monuments for Upper Egypt and Nubia while still in his 20s. Later Carter advised Theodore Davis, a wealthy American, to finance the excavation of the Valley of the Kings, which he agreed to do in 1902. This now-famous valley houses the remains of kings, queens, and nobles from Egypt’s New Kingdom (c. 1550 to 1100 BCE). Carter himself, however, landed in some trouble surrounding a dispute between site guards and unruly tourists; he lost his job in 1905.

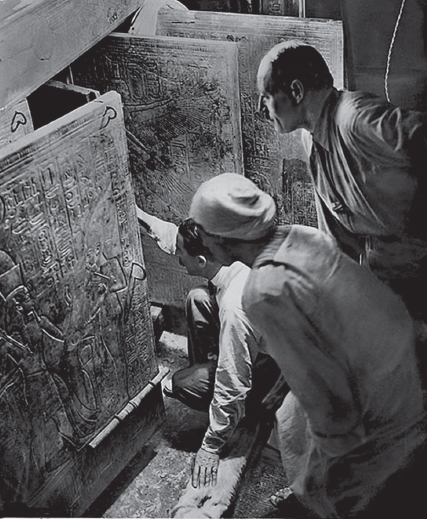

Carter, kneeling at center above, opens Tutankhamun’s tomb. The opening was the culmination of years of dedicated effort. Carter, who had become somewhat obsessed with finding the burial place of an obscure young pharaoh, saw his efforts pay off. It would take 10 years just to catalog all of the artifacts from this one magnificent tomb, which are currently in the Egyptian Antiquities Museum in Cairo.

The Second Door

By 1914 Theodore Davis had abandoned his excavations, and Lord Carnarvon, an English aristocrat, snapped up the concession. Interested in financing digs in the Valley of the Kings, he and Carter made a perfect pair.

World War I made it impossible to begin work until 1917. Then Carter began to dig, moving hundreds of tons of rubble left from earlier digs, but to no avail: the pharaohs held their secrets close. By 1922 Carnarvon felt he had poured enough money into the Valley of the Kings. Carter begged for one more chance.

On November 4, 1922, Carter began new excavations, digging a ditch southward from the tomb of Rameses IV. Just days later, on November 7, the workmen uncovered a step, below the foundations of some huts Carter had discovered in an earlier dig. By the evening 12 steps had been revealed, leading to a sealed stone gate. Carter sent a telegram to Carnarvon in England, and Carnarvon arrived just over two weeks later. Together Carnarvon and Carter broke their way through the sealed gate, now in a state of increasing excitement as they realized that this tomb had gone unnoticed (and thus unplundered) by grave robbers. Thirty feet below the gate, they came upon a second door.

At left, Carter and a helper work beside Tut’s coffin, removing the consecration oils, which covered the third, or innermost coffin.

With trembling hands, Carter scraped a hole in the debris in the doorway’s upper corner and peered through; the candlelight showed him an antechamber with strange animal statues and objects of gold. It was here that they found the tablet with the inscription: DEATH WILL SLAY WITH HIS WINGS WHOEVER DISTURBS THE PEACE OF THE PHARAOH. Carter recorded the discovery, but the pair, afraid rumors of the inscription would terrify the workmen, removed it. A statue of the god Horus also carried an inscription, stating that it was the protector of the grave. On February 17, 1923, it took two hours to chisel a hole into the burial chamber. Though only two sets of folding doors separated them from the magnificent gold sarcophagus—soon to become world-famous—they decided to leave it until later.

Carnarvon’s Strange Death

Lord Carnarvon was never to see the golden resting place of Tutankhamun’s body, for that April he fell ill, possibly due to a mosquito bite. At breakfast one morning in late March he had a 104° temperature, and it continued for 12 days. Howard Carter was sent for. Carnarvon died just before 2:00 AM on April 5, 1923. As the family came to his bedside, summoned by a nurse, all the lights suddenly went out, and they were forced to light candles. Later they discovered that the power failure had affected all of Cairo.

According to Carnarvon’s son, another peculiar event took place that night; back in England, Carnarvon’s favorite fox terrier began to howl, then died.

Lord Carnarvon

The Curse of the Pharaohs

The newspapers quickly began printing stories about the “curse of the pharaohs.” Arthur Mace, the American archaeologist who had helped unseal the tomb, began to complain of exhaustion soon after Carnarvon’s death; he fell into a coma and died not long after Carnarvon. George Jay Gould, son of the famous American financier, came to Egypt when he heard of Carnarvon’s death, and Carter took him to see the tomb. The next day Gould had a fever; by evening he was dead. Joel Wool, a British industrialist who visited the grave site, died of fever on his way back to England. Archibald Douglas Reid, a radiologist who x-rayed Tutankhamun’s mummy, suffered attacks of feebleness and died on his return to England in 1924.

George Jay Gould

Over the next few years 13 people who had helped open the grave also died, and by 1929 the figure had risen to 22. In 1929 Lady Carnarvon died of an “insect bite,” and Carter’s secretary Richard Bethell was found dead of a circulatory collapse. Professor Douglas Derry, one of two scientists who performed the autopsy on Tutankhamun’s mummy, had died of circulatory collapse in 1925; the other scientist, Alfred Lucas, died of a heart attack at about the same time.

Lady Carnarvon

Was the curse of the pharaohs a reality? Given the number of unexpected deaths, it is hard not to consider the possibility.

The one man who seemed to have escaped the curse of the pharaohs: Harold Carter