(1698–1703)

On Thursday, September 18, 1698, Lieutenant Étienne du Junca, an official of the Bastille in Paris, noted in his journal the arrival of the prison’s new governor, Bénigne d’Auvergne de Saint-Mars. Du Junca also noted that with Saint-Mars was a longtime prisoner from his previous post. Du Junca wrote that Saint-Mars “brought with him, in a litter, [a man] whom he had in custody in Pinerolo, and whom he kept always masked, and whose name has not been given to me, nor recorded.” Knowing that Saint-Mars had served at Pinerolo, a French-held fortress-prison near Turin, Italy, from 1665 to 1681, du Junca calculated that the masked man had been in prison for at least 18 years and possibly as long as 33.

The mysterious Man in the Iron Mask

Name Unknown

During his years in the Bastille, his jailers allowed the prisoner to attend Mass, but he always kept his face covered. When, five years after his arrival, on November 19, 1703, the prisoner died in the Bastille, du Junca, still Louis XIV’s chief jailer, still did not know the identity of the mysterious masked prisoner. He merely noted in his journal that the “unknown prisoner, who has worn a black velvet mask since his arrival here in 1698,” was dead and buried.

Mask of Velvet

Despite the popular misconception, the prisoner wore a mask made not of iron, but of black velvet. Alexandre Dumas was mainly responsible for propagating the inaccuracy with his 1847 novel The Man in the Iron Mask. According to the novel the prisoner was the twin brother of Louis XIV, born several hours later than the future king of France. That version of the story first appeared in Memoirs of the Duc de Richelieu, which is known to be a forgery by the duke of Richelieu’s secretary, the Abbé Soulavie, so the tale is probably an invention.

The masked prisoner aroused the public’s curiosity almost immediately. The first published account of the man in the mask was by Voltaire, who included it in his 1751 historical work The Century of Louis the Fourteenth. Voltaire recounts that in 1661, when the king was 23, a tall, aristocratic young man was incarcerated. He wore a riveted mask with a chin composed of steel springs, so that he could raise it to eat. But the king kept two musketeers posted to the prisoner’s side, ready to shoot him if he even made a move to remove the mask.

King Louis’s own sister-in-law, the Princess Palatine, shown left, was intrigued by the prisoner, writing to her aunt in 1711 that the prisoner had “two musketeers at his side to kill him if he removed his mask.” She had never met the prisoner before his death eight years earlier, but court rumors led her to believe that he was a refined man, who’d been treated well.

So who was the masked prisoner? Obviously he had to be someone against whom the king held a deep grudge and someone who would be recognized without the mask. In the nineteenth century one favorite theory proposed that he was Antonio Ercole Mattioli, an Italian courtier who had indiscreetly “leaked” the fact that the king was hoping to increase his Italian possessions. Louis concealed his rage at this piece of treachery and had Mattioli lured to Pinerolo. There he was seized and imprisoned for the rest of his life. That theory has to be abandoned, though. When Saint-Mars, the prison governor of Pinerolo, transferred to the Bastille, he took the mysterious prisoner with him. Records clearly show that Mattioli remained behind, locked in Pinerolo.

Antonio Ercole Mattioli.

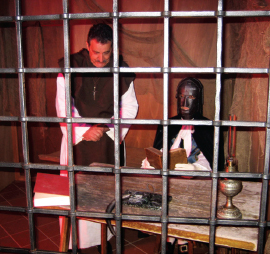

Although the famous prisoner wore a mask of velvet, every year the Italian town of Pinerolo hosts a festival celebrating the mystery of the Man in the Iron Mask. The festival includes reenactments inside the cell where the man spent his imprisonment in the Pinerolo fortress.

Over the years several historians have suggested one particularly interesting candidate for the man in the mask: the well-known playwright Molière.

This initially seems unlikely: Louis XIV had admired Molière from the time that he saw the playwright’s farce The Amorous Doctor presented at court in October 1658. The king also approved the staging of Molière’s Tartuffe, in spite of the disapproval of a religious faction (who were shocked by its presentation of a preacher as a hypocrite and lecher). But Molière won this battle in 1664—if Voltaire is right, three years after the man in the mask entered prison.

Molière died in 1673, at the age of 51, but we do not know with certainty when the man in the mask was actually imprisoned. It could even have been after Molière’s death. Yet it must be admitted that Voltaire’s description of the prisoner as being of “majestic height . . . and noble figure” hardly seems to fit the playwright in his 50s.

Playwright Molière

The Clue: The Mask

The likeliest key to the mystery is the necessity of the mask—no matter what it was made of. Why was the king so anxious that no one should see the prisoner’s face? In the days before cameras, when accurate likenesses of even the most famous people were not widely seen, to be assumed instantly recognizable to the public meant that someone was very high in the pecking order. And no one in those days was higher or more recognizable than Louis XIV himself. This explains why the twin brother theory has always been so popular.

Furthering the case for the look-alike relative were the long-standing tales about Louis XIV’s birth. His father, Louis XIII, did not like his wife, Anne of Austria, and, because he was not known to take mistresses, rumors floated that he must be either impotent or homosexual. There was therefore some anxiety about his ability to produce an heir to carry on the line. The queen’s lover, many believed, was the great Cardinal Mazarin. Some suspect that the notorious Cardinal Richelieu was also her lover.

When Anne conceived the child who became Louis XIV, everyone was astonished. After 23 years of marriage and four stillborn infants, the birth of Louis was so astonishing, in fact, that many contemporaries believed the true father to be Cardinal Richelieu or another “stud” who had impregnated her for the good of the royal line. And what better stud could there have been than the handsome young captain of Richelieu’s musketeers, François Dauger de Cavoye, who would demonstrate his potency by fathering six healthy sons on his wife?

Louis XIV, king of France

The Third Suspect: Eustace Dauger de Cavoye

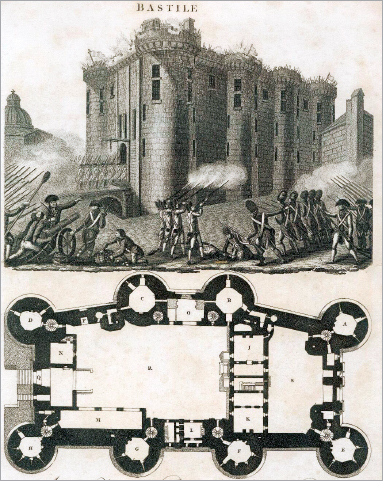

After the fall of the Bastille in July 1789, a commission searching for information about the masked prisoner studied its archives. Certain letters from prison officials seemed to point to the eldest son of François de Cavoye. Eustace Dauger de Cavoye had earned a reputation as a hell-raiser early in his adult life.

Eustace got in his first serious trouble in 1659, when he was 22, for being present at a black mass where a pig was christened and then eaten. The regard in which his mother was held at court averted serious consequences for the youth. But when Eustace killed a page boy in a quarrel six years later, he was forced to sell his commission. Several years after that, he landed in Pinerolo prison, but no one knows why.

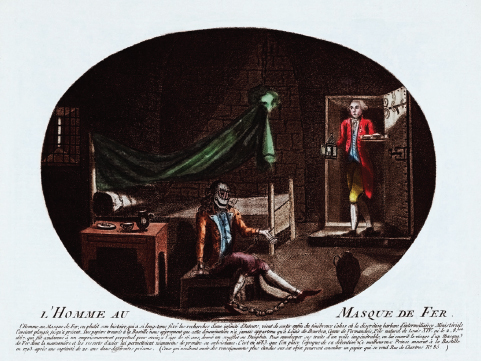

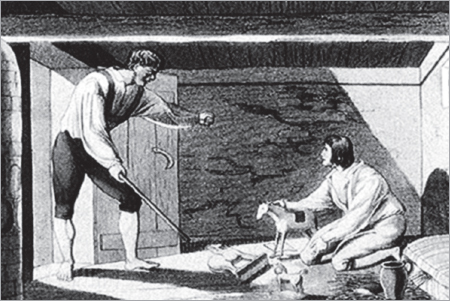

L’homme au masque de fer, or The Man in the Iron Mask. A French political cartoon from 1789 shows an iron-masked prisoner in chains sitting on a bench while a guard enters his cell in the Bastille carrying a tray of food. Its original caption identified the prisoner as Louis de Bourbon, comte de Vermandois, an illegitimate son of Louis XIV, who had died in 1683 at the age of 16. There is no evidence to support this claim, and historians posit that revolutionaries spread stories such as these to show how decadent nobles ill treated their own.

The Motive

If Eustace were the Man in the Iron Mask, then it looks as if he indulged in a folly that turned out to be the last straw. Is it conceivable that Eustace tried to exert pressure on the king to release his younger brother, also named Louis, who had been imprisoned for four years in the Bastille? But what pressure? What did he know that the king would have wanted to keep secret?

Surely the great secret must have been that he and King Louis had the same father. Consequently the king was illegitimate and had no right to the throne. If Eustace dared to even hint at it, Louis would have made sure that he never talked. That would explain why the prison governor had orders to kill the prisoner if he tried to speak with anyone.

There remains one obvious question: if it were Eustace, why did the king not simply have him executed? The answer must surely be that the sons of the captain of the guard were the king’s childhood playmates, and Louis must have had a certain feeling of affection for them. Eustace was safe . . . so long as he could not speak.

Drawing of the exterior and an interior floor plan of the Bastille

The Man Who Was Dr. Frankenstein

(1837)

June 16, 1816, had been a rather cool and cloudy spring day on Lake Geneva, Switzerland, and the five people on holiday at the Villa Diodati had built a large fire and lit all of the candles. With little else to do to entertain themselves—in those days people ate dinner at four in the afternoon—they decided to relax with an evening of scary tales.

The host, poet George Gordon, Lord Byron, never traveled without a small leather-bound volume of ghost stories, mostly German, called Fantasmagoriåa. He opened the book and began to read aloud a story about a bridegroom whose bride turns into a rotting corpse as he tries to embrace her.

Andrew Crosse

The Vampire

Byron’s “The Vampire” concerned a Greek aristocrat who undergoes a mock death and swears his traveling companion to secrecy. Later the companion witnesses his former friend doing some highly immoral things but feels bound by his oath of silence . . .

The physician Polidori—who was envious of Byron—stole the piece. He turned Byron’s work into a short novel called The Vampyr, which was published in a monthly magazine—and attributed to Byron. Later, the story was turned into a play that enjoyed immense success in London and Paris. (Polidori never made a penny.) London became mad for vampires, and novelist Bram Stoker capitalized. Polidori committed suicide a few years later.

Fertile Minds

Byron’s audience consisted of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley; Shelley’s future wife, 19-year-old Mary Godwin; Mary’s stepsister, Claire Clairmont; and Byron’s personal physician, John William Polidori. Claire was carrying Byron’s child—she had seduced him by the simple expedient of writing to him and offering to go to bed with him.

When they were all ready to retire, Byron had a suggestion for them: each should try to write a ghost story. The suggestion proved extra-ordinarily fruitful, for it not only led Mary to write a disturbing tale of a reanimated corpse (inspired by a dream), but it also induced Byron to write a story fragment called “The Vampire,” which triggered a literary trend that culminated, at the century’s end, in Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

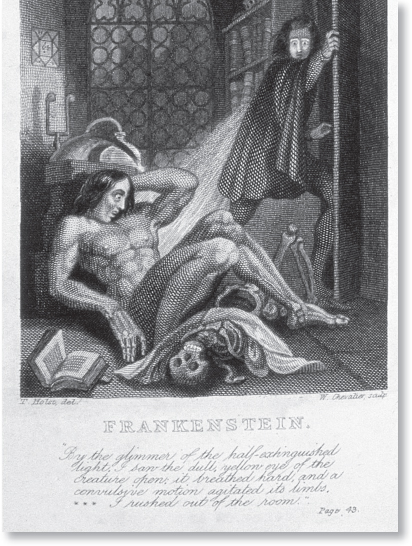

As for Mary, she developed her famous dream of a mad scientist who created a horrible monster with yellow eyes. The tale became a great success when published (anonymously at first) as Frankenstein, or, the Modern Prometheus in 1818.

Villa Diodati, “birthplace” of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

In 1823 H. M. Miller turned Frankenstein into a play. The stage monster looked so horrible that ladies fainted on opening night, and the monster’s makeup had to be toned down. The play went on to enjoy immense success at the Lyceum Theatre. Mary Shelley was not even consulted.

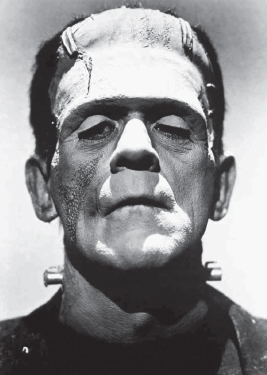

The Edison Stock Company made the first film version of Frankenstein in 1910. It was 10 minutes long. In 1915 the Ocean Film Corporation made a 60-minute version. But it was not until 1931 that Shelley’s story finally came into its own with the Boris Karloff film, made in Hollywood by Universal Studios and directed by an Englishman, James Whale. Whale had already filmed Dracula with Hungarian actor Bela Lugosi. It was an instant success, and Frankenstein was an obvious choice as a sequel. Lugosi was the main candidate to star as the monster, but he disliked the idea of playing a grunting brute after the articulate and sinister Count Dracula.

Frontispiece of the 1831 edition of Frankenstein

The Most Famous Frankenstein

James Whale, fresh from Lugosi’s refusal, happened to walk into the studio cafeteria at lunchtime when he spotted an English actor called William Pratt. Pratt was tall and in his mid-40s, with deep-set eyes and a strong face. He agreed to test for the part. The brilliant makeup artist James Pierce immediately saw possibilities in that powerful face and created from it the ghoulish and shambling creature we all know so well.

Pratt had already adopted the stage name Boris Karloff to shield his siblings, who worked in the foreign service, from the ignominy of having an actor in the family—and the name certainly suited the monster better than plain Bill Pratt.

As the monster Karloff was a sensation, fitting perfectly into a background of Gothic castles and bleak Teutonic landscapes. For the remaining 38 years of his life, Karloff was Hollywood’s best-known villain.

What Mary Shelley (who died in 1851) would have felt about Hollywood’s transformation of her best-known character into a symbol of evil is not difficult to guess. Her monster is a tragic, tormented human being, whose ambition—to love his fellow humans—is thwarted by his ugliness. Her monster is in no way evil.

As to the monster’s creator, Victor Frankenstein, Shelley never intended him to be the mad scientist of the Hollywood films, but a kind of tragic, poetic idealist, more like Mary’s husband than the frenetic genius Colin Clive played in the movie.

Boris Karloff in the 1931 film version of Frankenstein. Makeup artist James Pierce defined modern concepts of Shelley’s monster with the look he created for Karloff’s character.

The Man from Castle Frankenstein

Was Shelley’s tragic mad scientist merely a creature of nightmare? Not entirely. She apparently based him upon two real “mad” scientists: Johann Konrad Dippel, an alchemist and inventor who was actually born in Castle Frankenstein, near Darmstadt, Germany, in 1673, and Andrew Crosse, an Englishman who claimed to have created life in his laboratory.

The son of several generations of Lutheran pastors, Johann Dippel reportedly questioned the catechism at the age of 9. As a student of theology he earned high regard as a brilliant thinker. This, according to one biographer, made him conceited and self-willed and caused his later problems. In his 20s he discovered alchemy and set out to earn riches by making gold (in which, predictably, he failed). But one can gauge his skill as a chemist by the fact that he invented the dye called Prussian blue. In 1707 Dippel studied medicine at Leyden in southern Holland. He became a doctor and achieved considerable success in Amsterdam.

Dippel made the mistake of getting involved in politics, and authorities eventually had him imprisoned for seven years for heresy. He moved to Norway, where the duke of Wittgenstein provided him with an alchemical laboratory. He became convinced that he had discovered an elixir of long life, which led him to prophesy in early 1734, when he was 51, that he would live until 1808. Unfortunately he died, probably of a stroke, in April of the same year.

The ruins of Castle Frankenstein

The Other Frankenstein

Although the experiments that made him notorious took place more than two decades after Mary Godwin Shelley conceived her tale, she and her future husband had met the other candidate for the title of the “real” Dr. Frankenstein. Mary knew the man—Andrew Crosse—through a mutual friend. She and Shelley even attended Crosse’s lecture on the results of his experiments with atmospheric electricity two years before she began writing her book.

Andrew Crosse became one of the most hated men in England because of his attempts to create life in his laboratory. In this endeavor he apparently succeeded, but at great cost. Shunned by the academy and his neighbors, he became a virtual prisoner in his own home. When he died 18 years later, the secret of how he had created life died with him. And the episode remains one of the strangest and most baffling in the annals of science.

Mary Shelley, creator of the Frankenstein monster

Andrew Crosse, born in 1774, had inherited wealth and the beautiful manor house Fyne Court, near Broomfield, in Somerset, England. As a schoolboy he became fascinated by electricity, and he spent most of his adult life experimenting with it.

It was 21 years after Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein that Crosse performed the experiments that would make him famous—or infamous—throughout Europe and which earned him an entry in the Dictionary of National Biography.

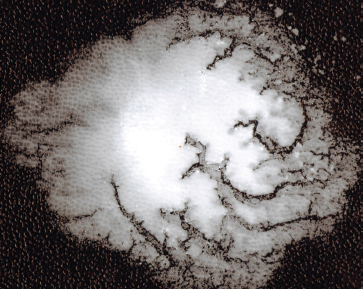

Crosse was attempting nothing more blasphemous than creating crystals of silica. He made glass out of ground flint and potassium carbonate, and then dissolved it in hydrochloric acid. His idea was to allow this fluid to drip slowly through a lump of porous stone that had been “electrified” by a battery and to see whether it formed crystals.

After two weeks he observed something odd happening to the lump of red-colored stone (it was, in fact, a piece of iron oxide from the slopes of Mount Vesuvius, chosen merely because it was porous). Small white “nipples” began to appear on it. These nipples began to grow tiny hairs, or filaments. They resembled minute insects, but Crosse knew that this was impossible. On the 28th day, he examined the rock through a magnifying glass and was staggered to see that the filaments were moving. And after a few more days, there could be no possible doubt: the minuscule creatures were walking around. Under a microscope, he could see that they were tiny bugs, the smaller of which had six legs, while the larger ones had eight.

Silica crystals

A New Species?

Crosse described his creatures as “the perfect insect, standing erect on a few bristles which formed its tail.” They looked to him to be part of the genus Acarus. Further experiments showed that the tiny organisms were able to reproduce themselves, but none of them lived beyond the first autumn frost.

Crosse sent off a paper about his experiments to the London Electrical Society. An electrician named W. H. Weeks, who lived at Sandwich in Kent, repeated the experiments and announced his results in Annals of Electricity as well as in the Transactions of the Society: he too had “grown” the mites.

Crosse spoke of his results to a local newspaper editor, who published a friendly report in the Western Gazette. In no time at all, for better or for worse, Crosse’s name was known throughout Europe.

Electron microscope image of a mite of the Acarus genus. Crosse thought that the “perfect insects” he’d spotted under his microscope were from this genus.

Let There Be Life

One of the most famous scenes in the film version of Frankenstein may be when flashes of lightning generate electricity that sparks life into the monster. That scene has as much in common with Crosse, who used electricity in his experiments, as it does with the Shelley book. In the novel, Dr. Frankenstein uses a combination of chemistry, alchemy, and electricity to produce life in his creature.

Most people were inclined to believe that Crosse was some kind of magician. He was even blamed for a potato blight that swept England’s West Country that year. Clergymen denounced him as an atheist and blasphemer, a “reviler of our holy religion,” who had presumptuously set himself up as a rival to the God in whom he disbelieved.

Crosse did his best to defend himself, pointing out that he was a “humble and lowly reverencer of that Great Being” and insisting that he had made his discovery by pure chance. It made no difference. Indignant locals destroyed his fences. One outraged clergyman, the Rev. Philip Smith, led his congregation to a hilltop above Fyne Court and proceeded to read the ceremony of exorcism. Crosse’s arrival on a horse interrupted the incensed preacher: the crowd instantly dispersed, no doubt convinced that Crosse could blight them with his magical powers.

Faraday, Too

In 1837 one of the greatest scientists of his day, Michael Faraday, defended Crosse at the Royal Institution. Faraday also claimed to have duplicated Crosse’s experiments and produced the mites. Yet even this sterling recommendation failed to silence the critics.

When it dawned on Crosse that it was now practically impossible to make the public aware of what he had really said and done, he decided that the simplest course was to withdraw in dignified silence.

Faraday in his laboratory. Faraday attempted to defend Crosse and his work to the British science academy, but even this well-respected scientist could not quell Crosse’s detractors.

“Surrounded by Death and Disease”

For the next 10 years Crosse led a bitter life. Both his wife and his brother fell ill and died in 1846. Crosse was a lonely man; most of his neighbors still shunned him. He was beset by financial worries—not, according to his own account, due to extravagance or excessive spending on scientific apparatus, but to his failure to pay enough attention to household expenditure, which he claimed had led to his being cheated. In a letter to the feminist writer Harriet Martineau in 1849—she wanted to write about his experiments—he described himself gloomily as “surrounded by death and disease.” Yet it was in that year, when he was 65 years old, that he accepted an invitation to dinner and found himself sitting next to a pretty, dark-haired girl in her 20s who was fascinated by science and by Crosse himself. Cornelia Burns became his second wife soon after they met.

The last six years of his life were relatively happy; he went to visit Faraday in London and received friends at Fyne Court. But a deep streak of pessimism persisted; one day he told his wife that he was convinced that this world was hell and that we are sent here because of sins committed in a previous existence. At that moment there was a violent flash of electricity in the room. This was not God rebuking him for his lack of faith, but merely the result of falling snow causing a short circuit in some of his electrical equipment.

Crosse died of a stroke, at the age of 71, in 1855.

Why Did It Work?

One of the great puzzles of science is why some experiments work for some people but not for others. Wilhelm Reich (1897–1957) once placed dry sterile hay in distilled water. After a day or two it was full of tiny living organisms, some even visible to the naked eye. When Reich studied the experiment through a microscope he found that the cells at the edge of the hay disintegrated into “bladders” and that the bladders tended to cluster together. He became convinced that the bladders were the basic unit of life and called them “bions.” Reich alleged that he was able to produce bions not only from organic substances like hay and egg white, but also from inorganic substances like earth and coke.

To silence skeptics who insisted that germs or minute living organisms from the air had contaminated his culture, he took the same precautions that Crosse took in his own experiments. He heated coke until it was red hot and then immersed it in a solution of potassium chloride; he claimed that the bions began to form immediately. These bions, he demonstrated, had an electrical charge, and were attracted to the anode or cathode of his apparatus. Reich finally concluded that his bions were not living cells but an intermediate form of life between dead and living matter.

Other scientists dismissed Reich as a crank, and he eventually landed in jail, where he died in 1957. Clearly, things had not changed much in the century between Crosse’s death and Reich’s.

Wilhelm Reich

Kaspar Hauser: The Boy from Nowhere

(1828–1833)

On Monday afternoon, May 26, 1828, a weary-looking youth appeared in the streets of Nuremberg, Bavaria. He was well built, but poorly dressed, and walked in a curious, stiff-limbed manner. He carried a letter addressed to the captain of the Fourth Squadron of the Sixth Cavalry Regiment. The shoemaker who found him took him to the regiment headquarters, but the youth was unable to answer questions, replying in a curious mumble. When Captain Wessenig arrived a few hours later, he found the place alive with excitement. No one could make heads or tails of their mysterious visitor. The youth had tried to touch a candle flame and screamed when his fingers burned. Offered beer and meat, he had stared at them uncomprehendingly, yet he had fallen ravenously on a meal of black bread and water. The only words the boy seemed to know were Weiss nicht (“I don’t know”). Asked his name, the boy wrote, “Kaspar Hauser.”

Kaspar Hauser

An Unlikely Visitor

The youth’s letter read: “Honored Captain. I send you a lad who wishes to serve his king in the army. He was brought to me on October 7, 1812. I am but a poor laborer with children of my own to rear. Since then I have never let him go outside the house.” The letter was unsigned.

Confounded, the cavalrymen locked him in a cell. Kaspar seemed perfectly content to sit there for hours without moving. He seemed to have no sense of time and only knew a few words. He could say that he wanted to become a Reiter (cavalryman) like his father—a phrase he had obviously been taught as if he were a parrot. Kaspar called every animal a horse, and when a visitor—one of the crowd who flocked to stare at him every day—gave him a toy horse, he adorned it with ribbons, played with it for hours, and pretended to feed it at every meal. He did not seem to know the difference between men and women, referring to both sexes as Jungen (boys).

Entrance to the house of Kaspar Hauser in Nuremberg, above, in a photograph taken in about 1860. At right, a contemporary illustration shows the shoemaker who found the boy presenting Kaspar to soldiers of the Fourth Squadron.

As he learned to speak, Kaspar gradually revealed his story. He stated that for as long as he could remember, he had lived in a small room, about 7 feet by 4 feet, with boarded-up windows. There was no bed, only a bundle of straw on the bare earth. The ceiling was so low that he could not stand upright. He saw no one. He would find bread and water in his cell each day. Sometimes his water had a bitter taste. If he drank this, he fell into a deep sleep, and when he woke up, he noticed that someone had changed his straw and cut his hair and nails while he had slept.

Kaspar’s only toys had been three wooden horses. A man had once entered his room and taught him to write his name and to repeat phrases such as “I want to be a soldier” and “I don’t know.” One day Kaspar woke up to find himself wearing the old clothes in which he was later found; the same man who had taught him to speak came and led him outside. The man promised him a big, live horse when he became a soldier and had abandoned him somewhere near the gates of Nuremberg.

At left, an 1839 painting of Hauser

Reading in the Dark

One of the most curious things about Kaspar was his incredible physical acuteness. He began to vomit if coffee or beer was in the same room; the sight or smell of meat produced nausea. The scent of wine literally made him drunk, and a single drop of brandy in his water made him sick. His hearing and eyesight were abnormally acute; he could even see in the dark and would later demonstrate his ability by reading from a Bible in a completely black room. He could feel different magnetic charges and identify them with the north or south pole. He could distinguish different metals by passing his hand over them, even when they were covered with a cloth.

At first Kaspar had seemed to be intellectually impaired. But the attention of visitors made him visibly more alert day by day—exactly like a baby learning from experience. His vocabulary increased and his physical clumsiness vanished. He learned to use scissors, quill pens, and matches. And as his intelligence increased, his features altered. He had struck most people as coarse, lumpish, clumsy, and oddly repulsive; now his facial characteristics changed and become more refined.

A contemporary illustration shows Kaspar in his cell with his wooden horses when a man arrives to teach him rudimentary German.

Suddenly Kaspar was famous, his case discussed throughout Germany. This must have worried whoever was responsible for turning him loose; his captor, or captors, had hoped that he would vanish quietly into the army and be forgotten; but now he was a national celebrity.

The town council decided he should be fed and clothed at the municipal expense, and housed him with the local schoolmaster, Friedrich Daumer. The town paid for thousands of handbills appealing for clues to his identity, even offering a reward. The police carefully searched the local countryside for his place of imprisonment, which was obviously within walking distance, but they found nothing.

A double statue of Kaspar Hausers in the old city center of Ansbach depicts him as the shuffling youth bearing his letter of introduction, foreground, and as a well-dressed gentleman, background left.

Trials and Tribulations

Then someone tried to kill him. On the afternoon of October 7, 1829, Kaspar was found in Daumer’s cellar, bleeding from a head wound, with his shirt torn to the waist. Later he described being attacked by a man wearing a silken mask, who had struck him either with a club or a knife.

Kaspar was moved to a new address, with two policemen to guard him. But now the novelty had worn off, and many in Nuremberg objected to supporting Kaspar.

One day a wealthy Englishman, Lord Stanhope, came to interview Kaspar. The two seemed to take an instant liking to one another; they began to dine out in restaurants, and Kaspar was often seen in Lord Stanhope’s carriage. Stanhope was convinced that Kaspar was of royal blood, and from 1831 to 1833 Stanhope presented Kaspar at many minor courts in Europe, where he never failed to arouse interest.

In 1833, back in Nuremberg, Stanhope asked permission to lodge him in the town of Ansbach, 25 miles away, where he would be tutored by Stanhope’s friend, Dr. Johann Meyer, and guarded by a certain Captain Hickel. Stanhope himself disappeared back to England.

Kaspar was miserable. He hated lessons and longed for the old life of courts and dinner parties. He seems to have felt that Ansbach was hardly better than the cell in which he had spent his early years.

Philip Henry Stanhope, Fourth Earl Stanhope. Lord Stanhope gained custody of Kaspar late in 1831 and spent a great deal of time trying to trace the young man’s origins. Even after he abandoned Kaspar in Ansbach, Stanhope continued to pay for Hauser’s living expenses.

On December 14, 1833, Kaspar staggered in from the snow to Meyer’s house gasping: “Man stabbed . . . knife . . . Hofgarten . . . gave purse . . . Go look quickly.” A hastily summoned doctor discovered that someone had stabbed Kaspar just below the ribs. Hickel rushed to the park where Kaspar had been walking, and found a silk purse containing a note, written in mirror writing. It said: “Hauser will be able to tell you how I look, whence I came and who I am. To spare him from that task I will tell you myself. I am from . . . on the Bavarian border . . . on the River . . . My name is M. L. O.”

But Kaspar could not tell them anything about the man’s identity. He could only explain that a laborer had delivered a message asking him to go to the Hofgarten. A tall, bewhiskered man wearing a black cloak had asked him, “Are you Kaspar Hauser?” and when he had nodded, the man handed him the purse. As Kaspar took it, the man stabbed him and then ran off.

Hickel revealed a fact that threw doubt on this story; there had only been one set of footprints—Kaspar’s—in the snow. But when two days later, on December 17, Kaspar slipped into a coma, his last words were: “I didn’t do it myself.” A few days before Christmas, Kaspar died.

A contemporary print illustrates the death of Kaspar Hauser

Who Was He?

One of the many learned men who examined Kaspar while he was alive was the lawyer and criminologist Anselm Ritter von Feuerbach. He concluded that Kaspar must be of royal blood. The favorite royal suspect was Karl, grand duke of Baden. The story claims that Karl’s stepmother, the Countess von Hochberg kidnapped Karl’s only male progeny to secure the throne for her own son. Could Kaspar have been the son of the grand duke’s?

Surely a more likely answer is that he was the illegitimate child of a respectable farmer’s daughter, terrified that her secret would become local gossip. In that case, who was behind the attacks? It is possible that they just never happened? After the first attack, in Daumer’s cellar, Nuremberg gossip suggested Kaspar’s wound was self-inflicted. By the time of the second attack, his fame was in decline, and he was desperately unhappy about his situation.

Kaspar had emerged from obscurity to find himself the center of attention. But although he was 17 years old, he was developmentally a 2-year-old boy. And undoubtably, certain aspects of his story are unlikely. Would a masked man find his way into the basement of Daumer’s house, then merely hit Kaspar on the head with a club? As to the second attack, Hickel’s assertion that there was only one set of footprints in the snow seems conclusive. And why was the mysterious letter written in mirror writing? Was it because Kaspar wrote it with his left hand, looking in a mirror, in order to disguise his writing? It is also unlikely that a paid assassin would write a letter at all. Is it not more likely that Kaspar, in a desperate state of unhappiness, decided to inflict a harmless wound but stabbed himself too deeply?

If so, Kaspar at least achieved what he wanted—universal sympathy and a place in history.

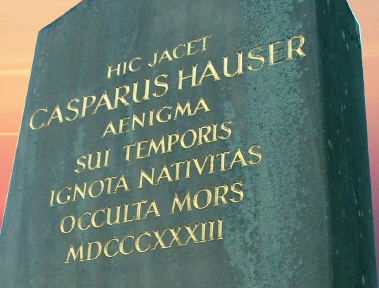

Kaspar’s gravestone reads, in Latin: Here lies Kaspar Hauser, riddle of his time. His birth was unknown, his death mysterious 1833. Another monument to him reads, “Here a mysterious one was killed in a mysterious manner.”

(1888)

The five Jack the Ripper murders, which occurred between August 31 and November 9, 1888, achieved worldwide notoriety. They also presented police with a new kind of horror: a killer who struck at random. When the biggest police operation in London’s history failed to catch the killer, the public hysteria was unprecedented. In the history of serial killer victims, Jack’s five barely makes a blip; subsequent killers have murdered dozens before getting caught or disappearing. But Jack himself continues to present an irresistible mystery for one simple reason: his identity is still unknown.

Jack the Ripper: identity unknown

The Victims

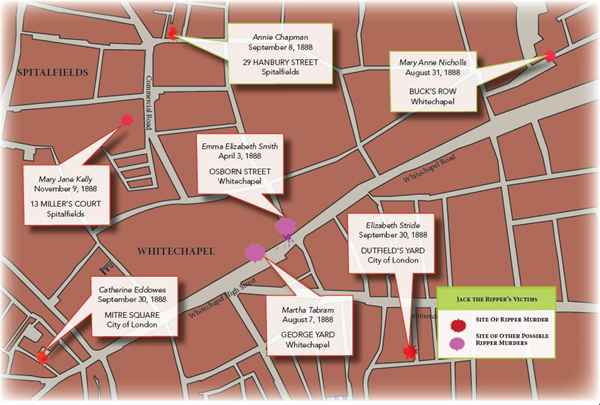

Although several other murders of women occurred in or near the Whitechapel district of London’s impoverished East End that summer and fall of 1888, nearly all “Ripperologists” agree that five particular murders were definitely the work of the single killer who called himself Jack the Ripper.

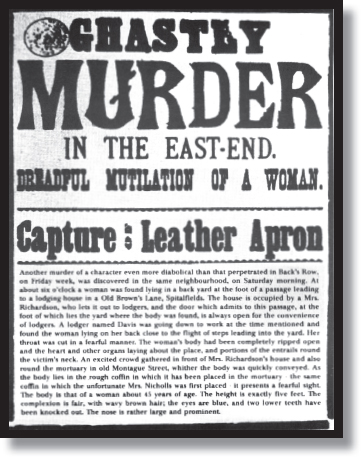

The first victim, a 43-year-old prostitute named Mary Anne Nicholls, was found in the early hours of August 31, 1888, in Buck’s Row, a slum street in Whitechapel. Her throat had been cut; in the mortuary doctors discovered that she had also been disemboweled.

The next victim was another prostitute, 47-year-old Annie Chapman. She was found a week after Nicholls, on September 8, spread-eagled in the backyard of a slum dwelling in the adjacent Spitalfields district. Her killer had ripped open her abdomen and removed her uterus. He’d also arranged the contents of her pockets around her in a curiously ritualistic manner—a characteristic act that forensics profilers have found to be typical of many serial killers.

The two murders engendered nationwide shock and outrage—nothing of this sort had ever happened before. That shock and outrage increased when, on the morning of September 30, 1888, the killer murdered two women in one night: Elizabeth Stride, 45, and Catherine Eddowes, 46. Within hours of the murders, someone claiming that he was the killer sent a letter to the London Central News Agency boasting of the “double event.” He signed the letter, “Jack the Ripper.”

As if in response to the sensation he was causing, the Ripper’s next murder was by far the most gruesome. He killed and disemboweled a 24-year-old prostitute named Mary Jane Kelly; the mutilation that followed must have taken several hours.

And then the murders ceased. Most people believed that the killer had committed suicide or had been confined to a mental home.

The body of the final victim—Mary Jane Kelly—was completely eviscerated.

From the point of view of the general public, the most alarming element about the murders was that the killer—almost certainly sexually motivated—seemed able to strike with impunity, and the police appeared to be completely helpless.

In 1988, a century after the Ripper murders, a television company in the United States produced a two-hour live special on the case. Two profilers from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), John Douglas and Roy Hazelwood, participated.

The Suspects

Douglas and Hazelwood sorted through a vast amount of evidence, including coroner’s reports, witness statements, police files, and photographs. In addition they were presented with a list of five prime suspects, which included Queen Victoria’s physician, Sir William Gull; heir to the throne, Prince Albert Victor; Roslyn Donston, a Satanist and occultist who lived in Whitechapel; Montague John Druitt, a melancholic schoolmaster who drowned himself a month after the last murder; and a psychotic Polish immigrant named Aaron Kosminski. Sir Melville Macnaghten, who became assistant chief constable at Scotland Yard soon after the murders, had listed the latter two as leading suspects in a memorandum dated February 23, 1894.

The FBI profilers dismissed most of these suspects on various grounds—for example, Gull had suffered a stroke that paralyzed his right side a year before the murders and would have been in no condition to prowl the streets. Prince Albert Victor had solid alibis: he wasn’t even in London at the time of the murders.

After analyzing the evidence Douglas and Hazelwood drew a forensics profile of the suspect, a technique now used regularly in law enforcement.

John Douglas explained that Jack was like a predatory animal who would be out nightly looking for weak and susceptible victims for his grotesque sexual fantasies. With such a killer, he said, one does not expect to see a definite time pattern because the murderer kills as opportunity presents itself. He added that such killers return to the scenes of their successful crimes.

Douglas also surmised that Jack was a white male in his mid-to-late 20s and of average intelligence. Douglas and Hazelwood agreed that Jack the Ripper wasn’t nearly as clever as he was lucky. Hazelwood thought that Jack was single, never married, and probably did not socialize with women at all. He would have had a great deal of difficulty interacting appropriately with anyone, but particularly women.

Hazelwood also conjectured that Jack lived very near the crime scenes—such offenders generally start killing within close proximity to their homes. Hazelwood also rejected theories that draw a picture of an educated doctor or surgeon who carved up his victims with a skill that belied his medical training. He assumed that if Jack were employed, it would have been at menial work requiring little or no contact with others.

He went on to say that, as a child, Jack probably set fires and abused animals and that as an adult his erratic behavior would have brought him to the attention of the police at some point.

Douglas added that Jack seemed to have come from a broken home, where a dominant female raised him. She physically abused him, possibly even sexually abused him. Jack would have internalized this abuse rather than act it out toward those closest to him.

A graffiti portrait of Jack the Ripper graces a wall in Spitalfields. The puzzling riddle of the Ripper’s identity still intrigues us today.

Filling Out the Profile

Douglas and Hazelwood continued filling in the details of Jack’s character and habits. Douglas described Jack as socially withdrawn, a loner, having poor personal hygiene and a disheveled appearance. Such characteristics are hallmarks of this type of offender. He said that people who know this type of person often report that he is nocturnal, preferring the hours of darkness to daytime. When he is out at night, he typically covers great distances on foot.

Hazelwood said that Jack simultaneously hated and feared women. They intimidated him, and his feeling of inadequacy was evident in the way he killed. Hazelwood noted that the Ripper had subdued and murdered his victims quickly. There was no evidence that he savored this part of his crime; he didn’t torture the women or prolong their deaths. He attacked suddenly and without warning, quickly cutting their throats.

The psychosexually pleasurable part came for him in the acts following death. By displacing or removing his victims’ sexual and internal organs, Jack was neutering or desexing them so that they were no longer women to be feared.

Poster warning area residents of the murders in the East End

The comments of the FBI profilers are fascinating in part because of the number of suspects they exclude. The first book about the case, The Mystery of Jack the Ripper (1929), hypothesized that the killer was a certain Dr. Stanley, who committed the murders because his son had died of venereal disease acquired from the last victim, Mary Kelly. But Mary Kelly was suffering from no sexually transmitted diseases. And no medical register of the period lists a “Dr. Stanley.”

In fact the murderer’s methods showed no signs of medical skill. And Hazelwood and Douglas’s theory of a mentally unstable, possibly psychotic, killer certainly fits the facts far better.

Knife believed to belong to the real Jack the Ripper. The murderer’s modus operandi showed no technical skill that would indicate that he was a surgeon or had any particular knowledge of anatomy.

The Arsenic Suspect

One of the most popular suspects of recent years was James Maybrick, the Liverpool cotton merchant who died of arsenic poisoning the year after the murders. A diary found in Liverpool in 1992 describes the events in gruesome detail, and its unnamed writer, who hints at being Maybrick, takes responsibility for the murders of Nicholls, Chapman, Stride, Eddowes, and Kelly, as well as two other women. Published as The Diary of Jack the Ripper, the entries certainly make Maybrick seem like a plausible Ripper. He was an arsenic addict (arsenic is a powerful stimulant in small quantities), and his frantic jealousy over his possibly unfaithful wife, Florence, 23 years his junior, might have unhinged him enough to make him strike out at any woman. But the handwriting of the diary was not remotely like Maybrick’s, and that seems to exclude him as a suspect.

James Maybrick

School’s Out

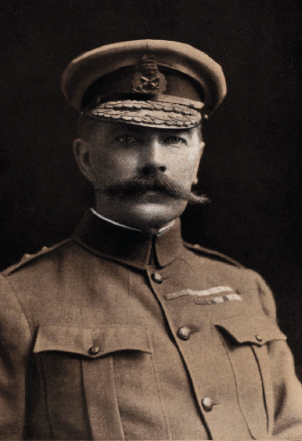

Another major suspect was Montague John Druitt, mentioned earlier as the “melancholic schoolmaster” who drowned himself in the Thames. Druitt’s name appears in Mysteries of Police and Crime (1898), a classic survey by Major Arthur Griffiths. Griffiths had known Sir Melville Macnaghten of Scotland Yard. In his memoirs Macnaghten mentions that there were three chief suspects, the leading one being the schoolmaster who drowned himself. Macnaghten does not name him, but a television interviewer, Dan Farson, succeeded in tracking down Macnaghten’s notes on the case and learned the name of the suspect: M. J. Druitt.

But the notes, to Farson, seemed to exclude rather than point the finger at Druitt. “When I looked up the passage in Macnaghten,” he explained, “I soon realized that he was totally ignorant of the facts. He said Druitt was a doctor who lived with his family; in fact, he was a schoolmaster and a failed barrister who lived in chambers. He also said that Druitt drowned himself the day after the murder of Mary Kelly.” Farson cites evidence against this, noting that the suicide took place three weeks later. He also cites a more plausible reason for Druitt’s suicide: “His mother had gone insane, and he believed he was going the same way.” So we must also dismiss Macnaghten and his suspect.

In pruning the list of suspects, Hazelwood and Douglas have come closer than anyone else has to solving the mystery of Jack the Ripper’s identity.

Sir Melville Macnaghten of Scotland Yard

Lord Kitchener’s Death—Accident or Murder?

(June 5, 1916)

He was one of the most visible and controversial figures of World War I. The United Kingdom’s secretary of war Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener, First Earl Kitchener, died on June 5, 1916, when the ship he was aboard, the HMS Hampshire, struck a mine and sank. Kitchener was en route to a meeting with the tsar of Russia to discuss plans to counteract some of the disasters suffered by the Russian armies in the previous year. One of the survivors, Fred Sims, recalled Kitchener standing impassively on deck, dressed in a greatcoat, awaiting the inevitable end. His body was never found.

Lord Kitchener

A Famous Face

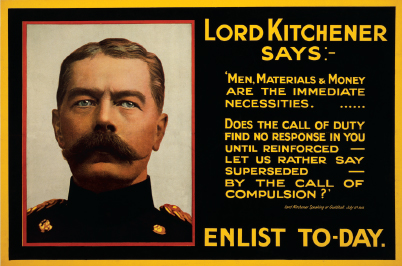

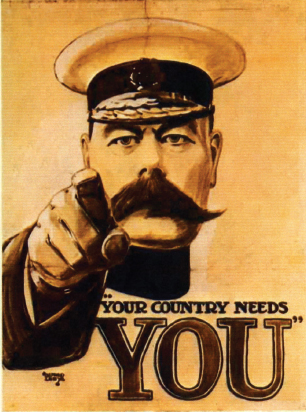

Kitchener’s face—with its heavy drooping moustache and piercing eyes—was iconic in Great Britain, where it had appeared on various recruiting posters (“Your Country Needs You!”). Kitchener had been one of the country’s great war heroes ever since he reconquered the Sudan in 1896 and avenged the death of General Gordon at Khartoum. After his conquest of the followers of the Mahdi in 1898 at Omdurman, Sudan, he was raised to the peerage as Baron Kitchener of Khartoum and Aspall. In the Boer War (1900–1902) Kitchener used fortified blockhouses and the systematic denudation of Boer lands to wear down the resistance of the guerrillas. His methods were severely criticized, but he was made a viscount and awarded $50,000 and the Order of Merit.

By the beginning of the war in 1914, Kitchener had been made an earl for distinguished services in India and Egypt. Appointed head of the War Office, he immediately laid plans to expand the British army from 20 to 70 divisions by recruiting men rather than the institution of a draft—hence the famous recruiting posters.

Kitchener, who was a strong believer in recruiting soldiers rather than drafting them, lent his image to enlistment posters.

Many had predicted that the “war to end all wars” would be over by Christmas 1914. Kitchener was one of few who predicted otherwise, foreseeing a long conflict. Kitchener was a difficult man and not easy to work with: he also had at least one political enemy. Chancellor David Lloyd George disliked Kitchener and felt that the British munitions industry needed a radical overhaul to compete with Germany in the war. He thought Kitchener was poorly suited to his role as overseer of munitions production, so he encouraged a powerful newspaper publisher, Lord Northcliffe, to play up the so-called Shell Scandal in the London Times and the Daily Mail.

Meanwhile, by Christmas 1914, incompetence and corruption had almost cost Russia the war. In June 1916 Russia was in serious trouble; money that should have been spent on munitions went into the pockets of government ministers. That summer Kitchener was dispatched to Russia to rein in Russia’s spending. But first he stopped at Scotland’s Scapa Flow—the United Kingdom’s primary naval base during the Great War—to meet with Admiral Sir John Rushworth Jellicoe, who had recently led the British Fleet to victory in the Battle of Jutland. By now Kitchener was a tired and worried man who may have had presentiments of death.

A Fateful Journey

The HMS Hampshire was to depart Scotland on June 5 for northern Russia. But when the weather deteriorated, it seemed advisable to postpone sailing for 24 hours. Kitchener would not hear of it and the route was changed.

So the doomed cruiser Hampshire set sail at 4:40 PM with Kitchener in a cheerful mood. He had declined to wait while minesweepers swept the channel. Soon after the ship left Scapa Flow the storm struck, and a northwest gale whipped the sea to a fury.

At about 7:45 PM the noise of the storm almost drowned out an explosion; one survivor later compared it to the sound of a lightbulb bursting. Then the lights failed, and the hiss of escaping steam filled the air. Rushing water trapped men in the engine room; some were scalded to death. Mutilated men staggered up onto the deck. The Hampshire had struck a mine. Witness saw Kitchener make his way to the deck, where he was last seen alive.

The news shocked Britain; homeowners drew their blinds and shops closed for the day. Army officers were ordered to wear mourning bands. When journalist Hannen Swaffer telephoned Lord Northcliffe to tell him of Kitchener’s death, Northcliffe replied, “Good. Now we can get on with winning the war.”

HMS Hampshire

Sabotage?

The most popular theory called the ship’s sinking sabotage. In February 1916, five months earlier, the Hampshire had been refitted in Belfast, Ireland. Kitchener had refused to allow Irish troops to wear a harp symbol on their uniforms, and it was reported that the Irish Republican Army had vowed to kill him.

In 1985 biographer Trevor Royle gained access to naval intelligence records. What he discovered confirmed the rumors that Kitchener’s death had not been simply bad luck. In spring 1916 a German listening post at Neuminster had picked up a naval signal from a British destroyer to the Admiralty declaring that a channel west of Orkney had been swept clear of mines. When the same signal was repeated twice, the Germans realized that the navy must have some important reason for sweeping the channel and reporting to the Admiralty. Admiral von Scheer of the German navy sent a U-boat commanded by Oberleutenant Kurt Beitzen to lay new mines in the recently cleared channel. One of these mines sank the Hampshire.

Royle discovered that naval intelligence had intercepted and read this signal from von Scheer (the British broke the German secret code). Also, on the day Kitchener was to sail, naval intelligence learned that the German submarine was still lurking in the area. Although three signals to this effect were sent to Admiral Jellicoe, for some reason Jellicoe allowed Kitchener to sail to almost certain death.

Was Lloyd George’s scheming part of a plot to send a rival to his death? The evidence undoubtedly establishes that Kitchener’s death can be laid at the door of Lloyd George and Jellicoe. But it seems unlikely that we can ever know for sure.

The Case of the Disappearing Mystery Writer

(1926)

In 1926 Agatha Christie became embroiled in a bizarre mystery that sounds like the plot of one of her own novels. But unlike the fictional crimes unraveled by Hercule Poirot or Jane Marple, this puzzle has never been satisfactorily solved.

At the age of 36, Agatha Christie seemed an enviable figure. An attractive redhead, she lived with her husband, Colonel Archibald Christie, in a magnificent country house that she once described as “a sort of millionaire-style Savoy suite transferred to the country.”

Dame Agatha Christie

The Queen of Crime

The “Queen of Crime,” as she came to be known, had been born Agatha Mary Clarissa Miller in Devon, England, in 1890. At the age of 24 she married Archibald Christie, an aviator in the Royal Flying Corps. During World War I, while Archie earned a reputation as a flying ace, Agatha worked in a hospital and a pharmacy. Shortly after the war ended, she gave birth to her only child, Rosalind, and a year after that she published her first novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles. By 1926 the Christies looked to the world to be a happy couple, living comfortably in Sunningdale, Berkshire. Yet that year the couple’s relationship—always a tumultuous one—hit a crisis.

A teenaged Christie in Paris, 1906

The Lady Vanishes

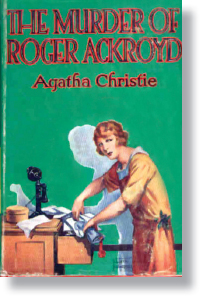

By this time, Christie had already authored several more volumes of detective fiction, but her latest, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, a best-seller, had caused some controversy because of its “unfair” ending. Much to her readers’ frustration, she used a plot device called an “unreliable narrator,” who turns out to be the assistant to Hercule Poirot, Dr. James Sheppard. Although Sheppard does not lie throughout the novel, he omits information that later reveals his guilt. Nevertheless, the clues are imbedded in the novel for readers to find. Critics loved it.

Although a moderately well-known author, Christie was hardly a celebrity yet; few of her books achieved sales of more than a few thousand. Then, on the freezing cold night of December 3, 1926, she left her home and disappeared. Suddenly the entire country was speculating about her whereabouts.

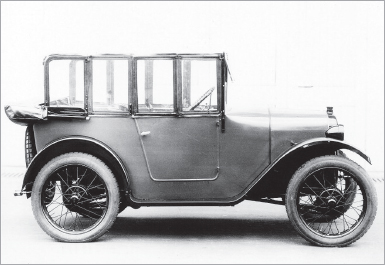

At 11:00 the next morning, a superintendent of the Surrey police received a report on a road accident at Newlands Corner, just outside Guildford. Agatha Christie’s car, a Morris two-seater, had been found halfway down a grassy bank with its bonnet buried in a clump of bushes. There was no sign of the driver, but Christie had clearly not intended to go far, because she had left her fur coat in the car.

By midafternoon the press had heard of the disappearance and besieged the Christie household. From the start the police hinted that they suspected suicide. Her husband dismissed this theory, sensibly pointing out that most people commit suicide at home, and do not drive off in the middle of the night. But the police organized an extensive search of the area around Newlands Corner and deep-sea divers investigated the Silent Pool, a seemingly bottomless lake in the vicinity.

Christie’s car, above, was found abandoned, with some of her possessions still inside but few clues as to her whereabouts.

Secret Stress

What nobody knew was that Christie’s life was not as enviable as it looked. Her husband had recently fallen in love with a girl who was 10 years younger than Christie, Nancy Neele. Earlier that year Archie told Agatha that he wanted a divorce. To make matters worse, Christies’s mother had recently died. Agatha was also sleeping badly, eating erratically, and moving furniture around the house haphazardly. She was obviously distraught, possibly on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

Agatha and Archibald Christie in 1919. Newspapers initially suspected Archie of foul play.

The Search Is On

The next two or three days produced no clues to her whereabouts. A report of women’s clothes in a lonely hut near Newlands Corner, together with a bottle labeled “opium,” caused a stampede of journalists. But it proved to be a false alarm; the opium turned out to be a harmless stomach remedy. Some newspapers hinted that Archibald Christie stood to gain much from the death of his wife, but he had a perfect alibi: he was at a weekend party in Surrey. Other journalists theorized that the disappearance was a publicity stunt. One acquaintance, Peter Ritchie-Calder, suspected that she had disappeared to spite her husband and bring his affair with Nancy Neele out into the open. Ritchie-Calder then read her novels to try to predict her next move. When the Daily Mirror offered a reward, reports of Christie sightings poured in. But they all proved to be false alarms.

The mystery deepened when Christie’s brother-in-law revealed that he had received a letter from her whose postmark indicated that it had been posted in London at 9:45 AM on the day after her disappearance, when she was presumably wandering around in the woods of Surrey.

An interview with her husband appeared in the Daily Mirror the following Sunday, in which he admitted, “that my wife had discussed the possibility of disappearing at will. Some time ago she told her sister, ‘I could disappear if I wished and set about it carefully . . .’” It began to look as if the disappearance, after all, might not be a matter of suicide or foul play.

Newspapers closely chronicled Christie’s disappearance, with some of them, such as the Daily Mirror, giving full front-page space to the story.

Lost and Found

On December 14, 11 days after her disappearance, the headwaiter in the Swan Hydropathic Hotel in Harrogate, North Yorkshire, looked closely at a female guest and recognized her from newspaper photographs as the missing novelist. He telephoned the Yorkshire police, who contacted her home. Colonel Christie took an afternoon train from London to Harrogate and learned that his wife had been staying in the hotel for a week and a half. She had taken a good room on the first floor at seven guineas a week and had apparently seemed “normal and happy,” and “sang, danced, played billiards, read the newspaper reports of the disappearance, chatted with her fellow guests, and went for walks.”

Agatha was reading a newspaper story about her own disappearance when her husband approached her. “She only seemed to regard him as an acquaintance whose identity she could not quite fix,” said the hotel’s manager. Archibald Christie told the press: “She has suffered from the most complete loss of memory, and I do not think she knows who she is.” A doctor later confirmed that she was suffering from amnesia. But Ritchie-Calder later remembered how little her behavior corresponded with the usual condition of amnesia. When she vanished, she had been wearing a green knitted skirt, a gray cardigan, and a velour hat, and carried a few pounds in her purse. When she was found, she was stylishly dressed and had £300 on her. She had told other guests in the hotel that she was a visitor named Teresa Neele from South Africa.

The Old Swan Hotel, formerly known as the Swan Hydropathic Hotel

There were unpleasant repercussions. A public outcry, orchestrated by the press, wanted to know who was to pay the £3,000, which the search was estimated to have cost, and Surrey taxpayers blamed the next big increase on her. Her next novel, The Big Four, received unfriendly reviews, but nevertheless sold 9,000 copies—more than twice as many as The Murder of Roger Ackroyd. And from then on (as Elizabeth Walter has described in an essay called “The Case of the Escalating Sales”), her books sold in increasing quantities. By 1950 all of her books were enjoying a regular sale of more than 50,000 copies, and the final Miss Marple story, Sleeping Murder, had a first printing of 60,000.

The twist ending, such as the one Christie used in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, greatly influenced the detective novel genre.

Agatha Christie at work on a novel during the 1950s. Cynics say that Christie’s disappearing act boosted her sales and kept her writing.

Christie’s second husband, archaeologist Max Mallowan

The Mystery of Success

Agatha Christie divorced her husband (who wed Nancy Neele) and in 1930 married Professor Sir Max Mallowan. But for the rest of her life she refused to discuss her disappearance and would only grant interviews on condition that it was not mentioned. Her biographer, Janet Morgan, accepts that Christie had a nervous breakdown, followed by amnesia. Yet this is difficult to fully accept. Where did she obtain the clothes and money to go to Harrogate? Why did she register under the surname of her husband’s mistress? And is it possible to believe that her amnesia was so complete that, while behaving normally, she was able to read accounts of her own disappearance, look at photographs of herself, and still not even suspect her identity?

Ritchie-Calder, who got to know her very well later in life, remains convinced that “her disappearance was calculated in the classic style of her detective stories.” A television play produced after her death even speculated that the disappearance was part of a plot to murder Nancy Neele. The only thing that is certain about “the case of the disappearing mystery writer” is that it may have helped her become the best-selling fiction author of all time.