(1400s to present)

On the morning of July 2, 1951, Pansy Carpenter, owner of the Allamanda Apartments in Saint Petersburg, Florida, noticed a strange odor. She tried the door of a tenant’s apartment—67-year-old Mary Reeser—and shrieked: the metal doorknob was searingly hot. Stepping through the open door, Carpenter saw, through the haze of superheated air, what was left of Mary Reeser.

Can a human spontaneously ignite?

Mary Reeser

Fire had reduced Reeser, a robust woman; the well-stuffed armchair in which she had been sitting; and the side table beside it to a pile of fine ashes interspersed with blackened, heat-eroded chair springs. The carpet bore a 6-foot circle burned away around the woman’s remains. The ashes still glowed red-hot.

A moist, slightly sticky black soot coated everything above a line 4 feet from the floor. Below that demarcation, the room was virtually undamaged—heat had slightly darkened only the paint on the wall immediately behind the armchair.

Plastic fittings above the smoke-line had melted like candle wax, but a pile of newspapers, just outside the scorched circle, was not even browned. And just outside the area of burned carpet lay a severed, but wholly untouched left foot, still inside its slipper.

Reeser had simply turned to ash, evidently burning not like a bonfire, but like a smoldering cigar.

Explaining the Impossible

There was no sign of gasoline or any other accelerant on Reeser’s remains—in fact there was no evidence of suicide or any foul play in the strange burning.

The official explanation was that Reeser had dropped a cigarette onto her rayon nightclothes, which had ignited, killing her within seconds. The fat in her body then fueled the fire until she was just ash.

But this explanation created more questions than it answered. Chief among its critics was Wilton Krugman, professor of physical anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania. He wrote:

I find it hard to believe that a human body, once ignited, will literally consume itself. . . . [It will] burn itself out, as does a candlewick, guttering in the last residual pool of melted wax.

Only at 30,000°F-plus (over 16,600°C) have I seen bones fuse—or melt, so that it ran and became volatile. These are very great heats—they would sear, char, scorch, or otherwise mar or affect everything within a considerable radius. What I’m driving at is this: The terrific destruction of Mrs. Reeser’s body (bones included) must have been accompanied by such heat that the room itself should have been burned much more than it was.

Investigators sift through the ashy remains of Mary Reeser.

It may be that spontaneous human combustion (SHC)—human beings bursting into flame for no traceable reason—has occurred repeatedly, if very rarely, throughout history. Some of our ancestors thought that people who turned to a pile of ashes had incurred the anger of the gods and been struck by a thunderbolt. But could they have actually been victims of an unknown physical process within the body?

Documented examples of apparent SHC are rare, yet they crop up in history books with disturbing regularity. Indeed there are dozens of recorded cases.

For example, Thomas H. Bartholini’s 1654 pamphlet, Historiarum Anatomicarrum Rariorum, mentions “a knight [called] Polonus, during the time of good Queen Bona Sforza [who reigned in Milan from 1469 to 1476], consumed two ladles of strong wine, vomited a flame and was thereupon totally consumed.”

Nichole Millet, the alcoholic wife of an innkeeper in Rheims, France, had spontaneously combusted on February 20, 1725. A contemporary report noted that “a part of the head only, with a portion of the lower extremities and a few of the vertebrae, had escaped combustion. A foot and a half of the flooring under the body had been consumed, but a kneading-trough and a powder tub, which were very near the body, had sustained no injury.”

More recently, in 1997, in County Kerry, Ireland, the community nurse who regularly visited him found the charred remains of 76-year-old John O’Connor in his living room. His head, upper torso, and feet were unburned, and there was almost no fire or smoke damage to the furniture.

Witnessing the Flames

Rarely it seems, does anyone witness another person spontaneously combust. One case is that of Jeannie Saffin of Edmonton, London. On the afternoon of September 15, 1982, 82-year-old Jack Saffin noticed a flash of light as he and his daughter, 61-year-old Jeannie, sat in their kitchen. When he turned to ask Jeannie if she’d seen it too, he saw that flames had enveloped her face and hands. He dragged her to the sink in an effort to douse the flames and shouted to his son-in-law to come help. When EMTs arrived to take Jeannie to the hospital they saw that flames had not damaged the kitchen.

Jeannie, who was mentally disabled, died of severe burns eight days later. The police who investigated the case found no evidence of accelerants or even a reasonable source for the flames—in fact they could find no cause at all for Jeannie’s combustion.

Theories

Charles Dickens, in his 1853 novel Bleak House, killed off the villainous miser Krook with spontaneous combustion. Although heavily criticized by some scientists for “giving currency to vulgar error,” Dickens was unrepentant. He had reported on a case of apparent SHC as a young journalist and felt the subject needed proper scientific investigation.

Unfortunately, given the rarity of apparent SHC cases (and its downright weirdness), little scientific research has been conducted on the subject. It has been noted that being elderly, overweight, and alcoholic seems to increase one’s risk of such a death, but this is by no means always the case.

Suggested explanations range from ball-lightning strikes to static electricity buildup to, of course, the perennial wrath of God. But no conclusive proof exists.

At present the only theory to enjoy any level of scientific acceptance is the “wick effect.” It suggests that something—such as a cigarette—ignites the victim’s clothes. The resulting flame releases melted fat from the dead victim’s flesh into the cloth of the clothes, and this then burns steadily, like a candlewick, until fire reduces all of the fat, and the body, to greasy ashes.

Illustration of the fiery death of Krook, a rag and bottle merchant, in Dickens’s Bleak House

Crop Circles: UFOs, Whirlwinds, or Hoaxers?

(1678 to present)

On August 14, 1980, farmer John Scull, of Westbury in Wiltshire, England, found a field of his oats crushed to the ground in three large circles, each 60 feet in diameter. Close examination of the flattened cereal revealed that the circles had not been made at the same time—that in fact, the damage had been spread over a period of two or three months, probably between May and the end of July of that year. The edges of the circles were sharply defined, and all the grain within the circles was flattened in the same direction, creating a clockwise swirling effect around the centers. None of the oats had been cut—merely flattened. The effect might have been produced by a very tall, strong man standing in the center of each circle and swinging a heavy weight around on a long piece of rope.

Inside a crop circle

A Hoax Unearthed

Now the national press began to cover the phenomena, and the British public soon became familiar with the strange circle formations. Unidentified Flying Object (UFO) enthusiasts appeared on television explaining their view: that the phenomena could be explained only by flying saucers. Skeptics preferred the notion of fraud. This latter view seemed to be confirmed when circles found at Bratton turned out to be a hoax sponsored by the Daily Mirror; a family named Shepherd had been paid to duplicate other Bratton circles. They did this by entering the field on stilts and trampling the crops underfoot. But, significantly, the hoax was quickly detected by Bob Rickard, the editor of an anomaly magazine, the Fortean Times, who noted the telltale signs of human intruders.

One of the many Wiltshire, England, crop circles

Dr. Terence Meaden, an atmospheric physicist, suggested that the circles had been produced by a summer whirlwind. Such wind effects are not uncommon on open farmland. But Dr. Meaden had to admit that he had never seen or heard of a whirlwind creating circles.

Moreover, it was noted that the center point on all three circles was off center by as much as 4 feet. The swirling patterns around these points were therefore oval, not circular. This seemed to contradict another theory, namely that vandals had caused the damage; vandals would hardly go to the trouble of creating precise ellipses.

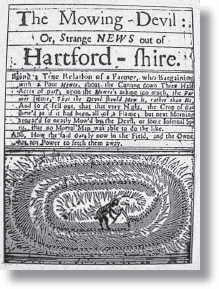

The Mowing Devil

Did crop circles first appear in 1678? This British pamphlet, or “chapbook,” tells a fable about a miserly farmer, too cheap to pay a laborer to cut his oats. “That the Devil himself should Mow his oats before he [the worker] should have anything to do with them!” said the farmer. But he would pay for invoking the name of the wicked one. That night, the oat field seemed to be on fire, but the next morning, the oats had been cut in circles, with every stem placed neatly. This frightened the cheap farmer so much that he was too afraid to gather the harvest.

A Pattern Forms

On August 19, 1981, another three-circle formation appeared in a wheat field below Cheesefoot Head, near Winchester in Hampshire. These circles had been created simultaneously and, unlike the widely dispersed circles in Wiltshire, were in close formation—one circle measured 60 feet across with two 25-foot circles on either side. But the sides of these circles had the same precise edges as the Wiltshire circles, and again, the swirl of the flattened plants was slightly off center, creating ellipses.

A group of three circles appeared in a wheat field in the Hampshire village of Cheesefoot Head in 1981, and many others have since formed there. One researcher spoke to a retired area farmer who said that crop circles have been appearing in Cheesefoot Head fields since 1922.

Over the next two years the number of circles in Great Britain increased, as did their complexity. And in the next decades, the circles would show up in more places and in many forms. There were crop circles with “rings” around them—flattened pathways several feet wide that ran around the outer edge in neat circles. Some even appeared with two or three such rings. Quintuplet formations and “singletons” also continued to appear.

It began to look as if whoever—or whatever—was creating the circles took pleasure in taunting the investigators. When believers in the whirlwind theory pointed out that the swirling had so far been clockwise, a counterclockwise circle promptly appeared. When it was suggested that a hoaxer might be making the circles with the aid of a helicopter, a crop circle was found directly beneath a power line. When an aerial photographer named Busty Taylor mentioned that he would like to see a formation in the shape of a Celtic cross, a Celtic cross appeared the next day. And, as if to rule out all possibility of natural causes, one “sextuplet” in Hampshire in 1990 had keylike objects sticking out of the sides, producing the impression of an ancient pictogram.

An aerial view of the crop circle formation at Avebury Manor, Wiltshire, which appeared in July 2008. Some observers interpret the pattern as if it were an ancient pictogram depiction of our solar-system as it will appear December 21, 2012—the date many believe is the last day of the Maya calendar.

What Can They Mean?

In a 1990 symposium, The Crop Circle Enigma, John Michell made the important suggestion that the crop circles have a meaning, which “is to be found in the way people are affected by them.” In conjunction with this idea, Michell noted that “Jung discerned the meaning of UFOs as agents and portents of changes in human thought patterns, and that function has been clearly inherited by crop circles.”

Crop circles originally cropped up in Great Britain, but they now appear all over the world, such as this one in the Vaud canton of Switzerland, in 2008. The mysterious circle of unknown origin swirls through a wheat field, attracting the curious to come investigate its patterns.

The Culprits Revealed?

In 1999 a gentleman from Southampton, England, came forward to take credit for at least some crop circles. Douglas Bower told the BBC that he, along with his friend David Chorley, had used a wooden plank to flatten crops and create the circles. He also said that the two men had been making the circles since 1991. Bower even demonstrated his technique for the cameras.

But rather than putting the matter to rest, Bower’s confession ignited the fury of some who remained convinced that the circles were the work of extraterrestrial beings.

Their Range Expands

Today it seems that an entire industry has grown up around crop circles. Web sites and books about the subject abound. Those who want to learn more can watch one of several documentaries and at least one feature-length film—the 2002 Signs, starring Mel Gibson. Enthusiasts can also participate in any of several conferences around the world, including the annual Glastonbury Symposium in the United Kingdom or the Independent Crop Circle Researchers’ Association conference in the United States.

The most recent development in the world of crop circles has nothing to do with their origin, but rather with commerce: today, companies ranging from Nike and Microsoft to Shredded Wheat have advertised their wares in fields across the world.

(1855)

On the morning of February 8, 1855, Albert Brailsford, the principal of the village school in Topsham, Devon, walked out of his front door to find that it had snowed in the night. He was intrigued to notice a line of footprints—or rather hoofprints—running down the village street. At first glance they looked like the ordinary hoofprints of a shod horse. A closer look revealed that this was impossible: the prints ran in a continuous line, one in front of the other. If it had been a horse, then it must have had only one leg and hopped along the street. And if the unknown creature had two legs, then it must have placed one carefully in front of the other, as if walking along a tightrope. Odder still, the prints—each about 4 inches long—were only about 8 inches apart. Each print was very distinct, as if it had been branded into the frozen snow with a hot iron.

The Devil’s cloven hooves

Over Hill, Over Dale

Brailsford alerted his neighbors, and soon a party of villagers was following the tracks southward through the snow. The villagers halted in astonishment when the hoofprints ended at a brick wall. They were even more baffled when someone discovered that the prints continued on the other side of the wall and that the snow atop the wall was undisturbed. The tracks also approached a haystack and continued on the other side of that, although the hay remained neat and tidy. The prints passed under gooseberry bushes and were even seen on rooftops. It looked as if some practical joker had decided to set the village of Topsham an insoluble puzzle.

The excited investigators tracked the prints for mile after mile over the Devon countryside. The prints wandered erratically through a number of small towns and villages. If it had been a practical joker, he would have had to cover about 100 miles, much of it through deep snow. Moreover, he would surely have hurried forward to cover the greatest distance possible. Yet the steps wandered, often approaching front doors, then going away again. At some point the creature had crossed the estuary of the river Exe; it looked as if it crossed between Lympstone and Powderham. Yet there were also footprints in Exmouth, farther south, as if it had turned back on its tracks. There was no logic in its meandering course.

The Devil’s Hoof

In places it looked as though the horseshoe had a split in it, suggesting a cloven hoof. There had been rumors at that time of a “devil-like” figure on the prowl in Devon. In the middle of the Victorian era, few country people doubted the existence of the Devil. Men armed with guns and pitchforks followed the trail; when night came villagers locked their doors and kept loaded shotguns at hand.

The Story Hits the Papers

A week later the story reached the newspapers. The London Times of February 16, 1855, carried an account of the hoofprints. The next day the Plymouth Gazette followed suit and mentioned one clergyman’s theory that the creature had been a kangaroo—he was apparently unaware that a kangaroo has claws. A report in the Exeter Flying Post made the slightly more plausible suggestion that the animal was a bird. Nevertheless, a correspondent in the Illustrated London News pointed out that no bird leaves a horseshoe-shaped print.

Also in the Illustrated London News, on March 3, the great naturalist and anatomist Richard Owen announced dogmatically that the footmarks were those of hind foot of a badger, without explaining why the badger hopped acrobatically on one hind foot. Another correspondent, who signed himself “Ornither,” was quite certain that a huge bird called the great bustard, whose outer toes were rounded, made the prints. But that still failed to explain why it walked 100 miles.

Great bustards

A Runaway Balloon?

Many theories arose to account for the hooflike prints, but for the superstitious, a simple, but far-fetched, answer was the most persuasive: the cloven hooves of the Devil himself had burned their marks into the snow. Nonetheless perhaps the likeliest hypothesis is one put forward by author Geoffrey Household, who edited a small book on the matter:

I think that Devonport dockyard released, by accident, some sort of experimental balloon. It broke free from its moorings, and trailed two shackles on the end of ropes. The impression left in the snow by these shackles went up the sides of houses, over haystacks, etc. . . . A Major Carter, a local man, tells me that his grandfather worked at Devonport at the time, and that the whole thing was hushed up because the balloon destroyed a number of conservatories, greenhouses, windows, etc.

Household goes on to say that the balloon finally came down at Honiton.

But a glance at the map of the footprints shows that they meandered in a kind of circle between Topsham and Exmouth. Would an escaped balloon drift so erratically? Surely its route would tend to follow a more or less straight line, in the direction of the prevailing wind—which, moreover, was blowing from the east.

The fact that it took a week for the first report to appear in print means that certain vital clues were lost forever. Now the only certainty seems to be that the mystery will never be solved.

What source would account for the hoofprints on rooftops?

(1871)

In the nineteenth century the Midwestern “Bible Belt” of the United States had more than its share of hell-and-damnation preachers, and many of them were predicting that the judgment and punishment visited on Sodom and Gomorrah would soon fall on all sinners. At the same time, the rolling farmlands and prairies of the Midwest have often been called “God’s own country,” largely because of the ubiquity and fervency of Christian worship in those states.

Strange, then, that it was not New York, San Francisco, or some other “Godless metropolis” that saw a catastrophe of both unexplained cause and Biblical destructiveness. It was the Midwest—at the height of the nineteenth-century Christian revival—that saw Hell come to Earth.

The Great Chicago Fire, view from the west

Jack-in-the-Box Inferno

The autumn of 1871 was hot and dry across the Midwest. From July into October the region had suffered a relentless drought. In the prairies to the south and west, from the booming new city of Chicago to the dense forests of northern Michigan, no rain had fallen, and in spite of the Great Lakes, humidity was at an all-time low. The desiccated atmosphere was dusty and harsh, the plants were parched brown, and Chicago’s ever-present wind offered no relief. City dwellers, unprepared for a drought lasting into the winter months, could only hope for rain, and they prayed that no fires would break out before the weather broke.

At 9:25 PM on the evening of October 8, 1871, Fire Marshall Williams and his crew were called to a blaze on DeKoven Street in Chicago’s lumber district. Although only a single barn, belonging to Patrick O’Leary, was on fire, Williams had good reason to fear that the conflagration might spread. Just the previous day, four whole blocks of the city had burned down, the wooden buildings igniting like dry tinder. As the firemen fought the O’Leary blaze they noticed the wind beginning to rise and worked frantically to bring the flames under control before sparks spread it far and wide.

Williams later reported that when the fire was halted “it would not have gone a foot further; but the next thing I knew they came and told me that St. Paul’s Church, about two blocks north, was on fire.” Once again, Williams doused the blaze before it could spread to neighboring buildings, but “the next thing I knew the fire was in Bateham’s planing-mill.”

Chicago residents streamed onto city bridges as they tried to escape the flames engulfing entire buildings.

The fire spread relentlessly: sparks from existing fires sometimes leapt whole blocks to settle on some distant building. The firefighters were familiar with this pattern, but this time the “leaps” seemed impossibly long. It was almost, said one, as if the sparks were coming down from the sky rather than from the burning houses.

The increasing gale fanned the fires, spread the sparks, and eventually grew strong enough to turn the water jets from the fire hoses into ineffectual drizzles. As the number of fires increased, any hope of getting them under control was finally abandoned. The Great Chicago Fire soon engulfed entire districts. Six-story buildings were reduced to ashes in less than five minutes. The hair, eyebrows, and clothes of firefighters smoldered in the heat. Temperatures climbed high enough to melt stone blocks, while several hundred tons of pig iron, piled on the riverbank 200 feet from the flames, fused into a solid mass.

While many people streamed out of the city, others, trapped by walls of flame, were forced to take shelter in the cold waters of Lake Michigan. At the same time thousands of terrified animals, penned in Chicago’s huge stockyards, broke free and stampeded through the streets, adding to the panic and confusion. Many of the scorched and blinded residents of Chicago were convinced that Judgment Day had arrived.

Map of Chicago, 1871. The darker area shows the destroyed districts.

Unnumbered Deaths

The unprecedented conditions produced unlikely phenomena: an onrushing wall of fire turned due south and ran half a mile into the howling gale; reporters noted that some buildings seemed to catch fire from the inside rather than the outside. One newspaperman said it looked “as though a regiment of incendiaries were at work. What latent power enkindled the inside of these advanced [distant] buildings while externally they were untouched?” One witness later said he believed that there was some unknown “food for fire in the air, something mysterious as yet and unexplainable. Whether it was atmospheric or electric is yet to be determined.”

For 27 hours the fire burned unchecked. Flames destroyed more than 17,500 of the city’s tightly packed wooden buildings, and 100,000 people were made homeless. The lost property was eventually estimated at $200 million—a near unimaginable figure in the nineteenth-century United States, when a house could be purchased for $50. Yet, incredibly, only 250 bodies were recovered. Even so, as historian Herbert Asbury later pointed out, this figure did not represent the final death toll: “At least as many more were believed to have been consumed by the fire, which in places reached temperatures as high as 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit.” Those temperatures can reduce a body to ash and bits of bone.

The Great Chicago Fire was the worst city blaze in U. S. history, but it was not the worst fire disaster. The near total destruction of a major metropolis (started, it was rumored, by Mrs. O’Leary’s cow kicking over a lamp) has, in the history books, almost entirely eclipsed a firestorm that ravaged eight states, destroyed countless acres of farmland, forest, and prairie, and killed more than 2,000 people. It is doubly strange that historians have neglected this disaster because it took place on the same night as the Great Chicago Fire, across most of the surrounding states.

Late in the evening, a little before O’Leary’s Chicago barn caught fire, a gale began to blow across the prairie from the southwest. Over the next few hours high winds pushed fires across Illinois, Iowa, Indiana, Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota, North Dakota, and South Dakota. Witnesses spoke of torrents of flame cascading from above and suffocating fogs of thick, black smoke that poured from a howling, crimson sky.

The luckiest of the stricken states were the Dakotas, Indiana, Illinois (outside Chicago), and Iowa. Here no human casualties were reported, but the loss of timberland and crops to flash fire was devastating.

Given the conditions, that there were no known fatalities in these states was little short of miraculous. Near the town of Yankton in South Dakota, for example, a wall of flame 30 feet high was seen sweeping before the wind as fast as a “fleet horse could run,” devouring everything in its path.

Scorched Earth

Minnesota was less fortunate. The counties of Carver, Wright, Meecher, and McLeod were inundated with flame, and the cities of Saint Paul and Minneapolis were both under dire threat during the night. Fifty state residents were reported killed by burning or suffocation.

Michigan, with its great forests, was half destroyed by fire. To the east of the state, between Saginaw Bay and Lake Huron, the fire reduced an area of some 1,400 square miles to scorched earth. Blazing forests cut off the towns along the shores of this area, and their inhabitants were forced to take to the water to escape. (Rescue boats out of Detroit were still picking up survivors several days later.) Eleven townships were partially destroyed and 12 more were completely lost in this area alone. Searchers later dug 50 bodies from the ashes.

To the west, down the shore of Lake Michigan, the towns of Muskegon, Manistee, Glen Haven, and Holland were set ablaze. The latter two towns were all but destroyed, and, around Holland, more than 200 farmsteads saw their land reduced to a burned waste.

In the center of Michigan, the city of Saginaw suffered $100,000 worth of fire damage, and the whole of the Saginaw Valley, south to Flint, was set ablaze. Only the combined male populations of Midland, Bay City, and Lansing managed to keep the blaze in check. Nonetheless the counties of Gratiot, Iosco, Alpena, and Alcona were devastated.

Dry prairie grass burns easily. In fact occasional fires play an important ecological role by removing trees and clearing dead grasses. In autumn 1871, however, conditions were ripe for unprecedented catastrophe.

Nowhere to Hide

Wisconsin was hardest hit. An area of at least 400 square miles between Brown County in the north and Marinette on Green Bay in the south was devastated, losing nine towns and four entire counties. Although this was less than a quarter the land damage suffered by Michigan, more than 1,000 people lost their lives in this area. About half of these were later found to have died not from burns, but from asphyxiation. The fires were so tremendous that they sucked the oxygen from the atmosphere and filled one of the greatest open prairies in the world with enough smoke to kill.

The Heart of the Firestorm

Of the 78 inhabitants of the village of Williamsonville, Wisconsin, only 4 survived that night. In the town of Menekaune, dozens of people who could not reach the relative safety of the bay died amid the blazing houses. At Williamson’s Mills almost every member of 14 families perished; 32 people desperately threw themselves down the settlement’s well—all were found dead. In the Sugar Bush settlements more than 260 people were killed; many were found suffocated but otherwise unmarked in areas some distance from the flames.

It was, however, in the town of Peshtigo that the most terrible losses of the night were incurred. In 1871, Peshtigo was a growing metropolis of more than 2,000 people. It maintained 15 hotels and shops, several factories, and 350 homes. By the morning of October 9, not a single building remained.

Survivors later told of a cloudless evening with a wind strong enough to shake the wooden houses. Around 9:30 PM a red glare came into view to the southwest; it expanded and filled the sky as it approached with the storm. A swelling rumble that soon reached the pitch of continuous thunder accompanied the crimson light. In the last moments before the catastrophe, sharp reports like distant cannon shots were heard—these were later identified as explosions of methane as the firestorm passed over neighboring marshes. In the last seconds the whoosh and crash of igniting and falling trees filled the air. Then the firestorm engulfed Peshtigo.

An illustration from the November 25, 1871, edition of Harper’s Weekly magazine shows the confusion and chaos as frantic humans and terrified animals try to find shelter from the fast-moving inferno.

One of the few survivors of the great blaze in Peshtigo gave this description of the first few moments of the destruction:

In one awful instant a great flame shot up in the western heavens, and in countless fiery tongues struck downward into the village, piercing every object that stood in the town like a red-hot bolt. A deafening roar, mingled with blasts of electric flame, filled the air and paralyzed every soul in the place. There was no beginning to the work of ruin; the flaming whirlwind swirled in an instant through the town. All heard the first inexplicable roar, some aver that the earth shook, while a few avow that the heavens opened and the fire rained down from above. The tornado was but momentary, but was succeeded by maelstroms of fire, smoke, cinders and red-hot sand that blistered the flesh.

The superheated blast ripped the roofs from the houses, setting them ablaze before they hit the ground. Unshielded buildings, animals, and people exploded into flame where they stood. Even the citizens who were protected from the direct blast of the storm were choked by black whirlwinds of smoke or suffocated as the burning air seared their lungs.

One house on the edge of town was whipped straight up into the air. Witnesses said that the walls of flame around the town met to form a dome of fire, and that at about 100 feet above the ground the flying house burst into flames and was torn to pieces.

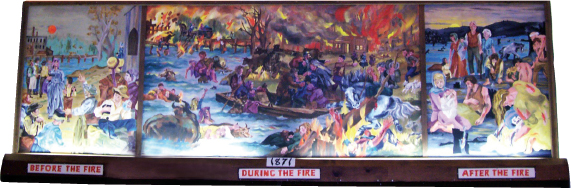

Below, the Peshtigo River, which runs through the town. The mural at left, which can be seen at the Peshtigo Fire Museum, shows the town residents jumping into the river during the height of the firestorm.

Panic

After the first onslaught, Peshtigo’s firestorm slackened a little. Several firefighters even tried to deploy a fire hose, but it burst into flames and was reduced to melted rubber before they could start pumping the water.

For those who were not already dead or incapacitated, the only hope of survival was reaching the watery safety of the Peshtigo River, which ran through the center of the town. Finding a way there, however, was a problem. Nearly every town landmark was ablaze. Smoke filled the rushing air like black fog. Nowhere in the open was safe, as wild gusts of wind hurled tongues of fire as if from a flamethrower. Finally, those who did not cover their mouths when they breathed risked scorching their lungs too badly to ever take another breath.

Two mobs of terrified evacuees met in the middle of the wooden bridge that spanned the river. In the grim confusion the groups fought to pass one another, both convinced that the far side must be safer than the inferno that they were trying to escape. As panicked people strove to find a path to safety, the bridge, which was itself in flames, buckled and collapsed.

One man managed to keep his head in the surrounding panic. Seeing that his sick wife could never make it to the river on foot, he and their five children pushed her, bed and all, out of the house and into the rushing water. They had trouble keeping her head above the surface, but the entire family survived.

Those who made it to the river were not out of danger. In those days, when bathing in public was still considered indecent, few men and almost no women knew how to swim. The flaming, smoke-laden air above the water was difficult to breathe, and the current swept burning debris toward the bobbing heads. Because this was a rural community, terrified horses and cows ran loose; many people died from trampling.

Outside the town an impenetrable wall of burning woodland blocked escape. Many people sought refuge in the few brick buildings, but these quickly turned into ovens, and the bones of the dead were later found amid the heat-shattered rubble. Only one group, which staggered into the swampy ground to the east of the town, managed to escape by lying flat in the hot and brackish, but protecting, water.

One farmer on the edge of town shot his family and then himself before the surrounding flames could close in. In another area, a desperate mother dug a hole in the earth with her bare hands, placed her baby in it, and then shielded the child with her own body. She burned to death; her baby suffocated.

In the early morning hours the firestorm abated. By dawn most of the fires were dying, but only because almost everything in the area had been reduced to ash or slag. Survivors suffering from burns, lacerations, and exposure saw a blackened landscape stretching as far as the eye could see. The final death count in Peshtigo was 1,152—more than half the town’s population.

A chunk of blackened white pine, which survived the Peshtigo Fire

Burning Air

Because the Great Chicago Fire commanded all national attention, it was several weeks before anything other than local help was offered to survivors in the rural areas. The governors of Michigan and Wisconsin were both forced to issue special proclamations begging for assistance. It was months before the terrible damage could be fully assessed. Indeed in some areas fires continued to burn for more than three weeks. Ashes from the conflagration were blown as far eastward as the Azores in the mid-Atlantic Ocean.

The official explanation for the calamity was a windstorm that carried sparks—originally from bush fires in the southern prairies, then from the fires caused by the storm itself.

Yet this theory seemed somehow inadequate. It failed to explain the sheer violence of the firestorm. Over recent centuries droughts have been recorded worldwide—some going on for decades—but nowhere have high winds and flying sparks created a conflagration like the one that struck the Midwest in 1871. Accounts such as that of Peshtigo seem to imply that the very air was ablaze. Witnesses of spontaneously combusting buildings in Chicago could only suggest invisible incendiaries or a mysterious “food for fire in the air,” as a cause. Moreover, the high incidence of death by suffocation, not only outdoors, but often far from burning areas, suggested to many that there may have been some deadly quality in the wind itself . . .

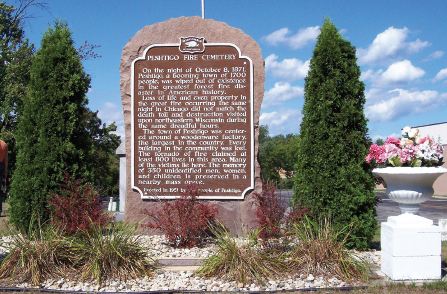

The State Historical Society of Wisconsin erected a memorial to the victims of the Peshtigo Fire at the Peshtigo Fire Cemetery.

Could there be any basis for suspecting that the catastrophic fires of autumn 1871 were caused by some rare atmospheric event? Or any of the other several unexplained heat blasts that have been recorded since the Great Midwest Firestorm?

The Spanish province of Almeria suffered a plague of bizarre fires, beginning on June 16, 1945. Throughout that day, around the town of La Roda, white clothing spread out to dry suddenly burst into flames. This had never been known to happen before, nor was any other shade or color of cloth affected.

During the next 20 days, more than 300 unexplained fires broke out in the area. Not just laundry, but farmhouses, barns, threshing bins—even the clothes on people’s backs burst into flame without visible cause. What was remarkable, though, was that in almost every case the object damaged had been white.

The government dispatched a team of scientists to the area, but when they unpacked a box containing their instruments it burst into flame. The rather disgruntled experts eventually reported that the fires might have been triggered by Saint Elmo’s fire (a harmless and heatless electrical discharge) or underground mineral deposits. The director of Spain’s National Geographic Institute connected the two theories when he noted that “the land [around La Roda] is a particularly good conductor of electricity.” He could not, however, explain why the area had only recently been plagued by incidents of spontaneous combustion if it were naturally prone to them. Obviously, even if they were on the right track, some unknown catalytic force was at work.

The intense heat blast that sent temperatures skyrocketing in Spain’s Almeria province seemed to affect only white objects or fabrics. Laundry spread to dry on the ground and hung on lines burst into flames with no visible source of ignition.

The Portuguese Furnace Blast

On July 6, 1949, something described as “an inferno-like blast” hit the town of Figueira, approximately 235 miles north of Lisbon on the central coast of Portugal. It took place was early morning—a time when most Portuguese housewives were out doing the day’s shopping, and few others were about. Suddenly, without warning or any apparent cause, the air temperature soared to an unbearable level: a naval officer who was working near the harbor reported a thermometer leaping from 100°F to 158°F in only a few seconds.

The heat blast was reported to have felt like “tongues of flame.” Hundreds of people were knocked senseless, while others prayed in terror or searched fruitlessly for somewhere cooler. Cattle and donkeys panicked, and thousands of poultry fell dead. The Mondego River, which discharges into the Atlantic at Figueira, steamed and even dried up at several shallow points. The Spanish press reported that in one place “millions of fish died in the mud that was rapidly becoming a sand bed.” Then, approximately two minutes after it hit, the heat wave passed like the lifting of a curtain.

But the mystery inferno had merely moved inland. Thirty miles from the coast, the town of Coimbra was roasted a short while later; there the scorching again lasted two minutes before passing, this time for good. No unusual winds, sun effects, or tectonic movements were noted immediately before, during, or after the event. The searing heat simply swept in from the clear sky over the sea, then vanished.

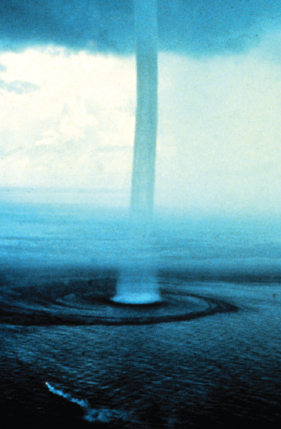

The Spanish press reported that on July 5, 1949—the day before the Portuguese heat blast in Figueira—a “great column of whirling wind of a luminous brown color struck a small settlement with a violent roar and kindled flames that leapt 30 feet high.” Unfortunately the newspaper did not give the name of the settlement, and the report therefore cannot be confirmed.

This event, however, seems to have been the climax of the spontaneous combustion plague in the Iberian Peninsula. Several minor fires were reported over the next few days, but by July 10, the phenomenon had apparently ceased altogether.

These stories might remind the modern reader of the heat blast that devastated Hiroshima after the dropping of the atomic bomb, minus, of course, the following air blast and radiation sickness. Indeed, UFOlogists have speculated that the Figueira and Almeria heat blasts might have been caused by aliens demonstrating their super-weapons for inscrutable reasons of their own. Certainly no known human technology at that time could have produced such short-lived, but intense heat waves. Even today, orbital lasers that could create such effects are only at the theoretical stage of development.

Discounting these unverifiable notions, there is still the possibility of freak atmospheric effects or even of another kind of intruder from space . . .

The Lashing Tail From Space

A few years after the Great Chicago Fire, Minnesota congressman and author Ignatius Donnelly made an interesting observation in his book Ragnarok. He noted that Biela’s comet, during its close brush with the earth’s gravity field in 1846, had split into two parts. The shattered comet was due to return in 1866, but, to the astonishment of astronomers, it failed to appear. Then in November 1872 (just over a year after the Great Midwest Firestorm), it reappeared unexpectedly in a spectacular and meteoric display. This might seem irrelevant to the events of 1871, except that the comet was missing its tail during the 1872 visit.

A comet is made up of a head of solid ice and a long tail of gases, ice particles, and space dust resembling the wake of a ship. Donnelly suggested that the 1846 brush with the earth had detached Biela’s tail, and that after the split, the comet’s head had been diverted into a slightly different orbital path, and the material of the tail continued orbiting the sun. Donnelly’s theory was that, 25 years later, on the night of October 8, 1871, the remains of the tail returned and plunged into the atmosphere over the Midwest. The burning, demon wind that ravaged eight states, he suggested, was a direct result of the atmospheric impact and superheating of a cloud of space debris.

Comet Biela, illustrated in 1846 by an observer

(1908)

On June 30, 1908, the inhabitants of Nizhut-Karelinsk, a small village in central Siberia, watched a bluish white streak of fire cut vertically across the sky. What began as a bright point of light lengthened over a period of 10 minutes until it seemed to split the sky in two. Then it shattered to form a monstrous cloud of black smoke. Seconds later a terrific roaring detonation set buildings to trembling.

They did not know it at the time, but those villagers had witnessed the greatest natural disaster in earth’s recorded history. If the object that caused what is now known as “the Great Siberian Explosion” had arrived a few hours earlier or later it might have landed in more heavily populated regions, taking millions of lives.

Trees flattened by the Tunguska explosion

The Aftershocks

As it later turned out, the village of Nizhut-Karelinsk, was actually 200 miles away from the “impact point,” and yet the explosion had shaken debris from the roofs of buildings. A Trans-Siberian express train stopped because the driver was convinced that the cars had derailed; seismographs in the town of Irkutsk indicated that an earthquake had struck.

The shock wave traveled around the globe twice before it died out, and its general effect on the weather in the northern hemisphere was far-reaching. During the rest of June it was so light out that it was quite possible to read the small print in the London Times at midnight.

For some months the world was treated to spectacular dawns and sunsets, as impressive as those that had been seen after the great Krakatoa eruption in 1883. From this, as well as the various reports of unusual cloud formations over the following months, it was clear that the event had thrown a good deal of dust into the atmosphere.

Kulik Investigates

It was not until World War I had been fought and the Russian Revolution had overthrown the tsarist regime that news of the extraordinary events of that June day finally reached the general public. In 1921, as part of Lenin’s general plan to place the Soviet Union at the forefront of world science, the Soviet Academy of Sciences commissioned mineralogist Leonid Kulik to investigate meteorite falls on Soviet territory. It was Kulik who stumbled upon the few brief reports in 10-year-old Siberian newspapers that finally led him to suspect that something extraordinary had happened in central Siberia in summer 1908.

In 1999 a team from the Russian Academy of Sciences plotted a new map of the fallen tree coordinates. From this image it determined that at least one, and possibly two, massive objects exploded over Siberia in 1908.

Kulik found the newspaper accounts of the event confusing and contradictory.

The reports described the ground opening up to release a great pillar of fire and smoke that burned brighter than the sun. Distant huts were blown down and reindeer herds scattered. A man plowing in an open field felt his shirt burning on his back, and others described being badly sunburned on one side of the face but not the other. Many people claimed that the noise had temporarily deafened them, others suffered the long-term effects of shock. Yet, almost unbelievably, not a single person had been killed or seriously injured. Whatever it was that produced the explosion had landed in one of the few places on earth where its catastrophic effect was minimized. A few hours later, and it could have obliterated Saint Petersburg, London, or New York. Even if it had landed in the sea, tidal waves might have destroyed whole coastal regions. On that June day the human race had escaped the greatest disaster in its history—and didn’t even know it.

Finally Kulik discovered that a local meteorologist had made an estimate of the point of impact, and in 1927 the Academy of Sciences gave him the necessary backing to find the site where the “great meteorite” had fallen.

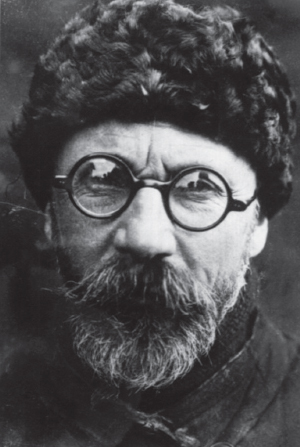

Leonid Kulik, the Russian mineralogist who first investigated the mysterious Tunguska event

Journey into Siberia

The Siberian forest is one of the least accessible places on Earth. Even today it remains largely unexplored; whole areas have been surveyed only from the air. What settlements there are can be found along the banks of its mighty rivers, some of them miles in width. The winters are ferociously cold; in the summer the ground becomes boggy, and the hum of mosquitoes fills the air. Kulik was faced with an almost impossible task: to travel by horses, sleds, and rafts with no idea of exactly what he was looking for or where to find it.

In March 1927 he reached the tiny village of Vanovara, about 100 miles from the estimated blast site. From there he set off, accompanied by two local guides who had witnessed the event. After many setbacks the three men arrived in April on the banks of the Mekirta River—the closest river to the impact point. In 1927 it formed a boundary between untouched forest and almost total devastation.

Even today, more than a century after the explosion, the Tunguska area is oddly barren

On that April day Kulik stood on a low hill and surveyed the destruction caused by the Tunguska explosion. For as far as he could see to the north, perhaps a dozen miles, not a single full-grown tree of what had once been dense forest remained standing. Every single one of them had been flattened by the blast. He also noticed an important fact: the flattened trees all lined up precisely facing the same direction, pointing southeast toward the horizon. It was obvious to him that this was just the edge of the devastation; the blast must have been far larger than even the wildest reports had suggested.

Kulik was eager to continue his exploration of the disaster and to search out its epicenter, but his two guides were terrified and refused to go on. So Kulik was forced to return to Vanovara with them. It was not until June that he managed to return with two new guides.

Even in 1927, nearly two decades after the event, rows of downed trees covered thousands of square miles of formerly dense forest.

The Cauldron

The second expedition followed the line of broken trees for several days until they came to a natural amphitheater in the hills and pitched camp there. They spent the next few days surveying the surrounding area; Kulik reached the conclusion that “the cauldron” as he called it, was the center of the blast. All around, the fallen trees faced away from it, and yet, incredibly, some trees actually remained standing although stripped and charred, at the very heart of the explosion.

The full extent of the desolation was now apparent: from the river to its central point was a distance of 37 miles. So the blast, Kulik calculated, had flattened more than 4,000 square miles of forest.

Still working on the supposition that a large meteorite had caused the explosion, Kulik began searching the area for its remains. He thought he had achieved his objective when he discovered a number of pits filled with water; he naturally assumed that fragments of the exploding meteorite had made them. But the holes were drained and found to be empty. One even had a tree stump at the bottom, proving it had not been made by a blast.

No Crater

Kulik was to make four expeditions to the area of the explosion, and until his death he remained convinced that an unusually large meteorite had caused it. Yet he never found the iron or rock fragments that would provide him with the evidence he needed. In fact he never succeeded in proving that anything had even struck the ground. There was evidence of two blast waves—the original explosion and the ballistic wave—and even of brief flash fires, yet there was no crater.

The lack of a crater only deepened the riddle. A 1938 aerial survey showed that only 770 square miles of forest had been flattened and that original trees were still standing in the spot where the crater should have been. This evidence suggested that the explosion was caused not by an enormous meteor but rather by a bomb.

Aerial photo of the area around the Tunguska site. Scientists at the University of Bologna now suspect a small lake, Cheko, to be the impact crater that Kulik couldn’t find.

Mysterious Meteorite

Even the way that the object fell to Earth was disputed. More than 700 eyewitnesses claimed that it changed course as it fell, saying that it was originally moving toward Lake Baikal before it swerved. Falling heavenly bodies have never been known to do this, nor is it possible to explain how it could have happened in terms of physical dynamics.

Another curious element about the explosion was its effect on the trees and insect life in the blast area. Trees that had survived the explosion had either stopped growing, or were shooting up at a greatly accelerated rate. Later studies revealed new species of ants and other insects that are peculiar to the Tunguska blast region.

A meteoroid pierces the earth’s atmosphere.

The Sky is Falling

It was not until some years after Kulik’s death in a German prisoner-of-war camp that scientists began to see similarities between the Tunguska event and two other, more catastrophic, explosions: the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki with thermonuclear devices. Our knowledge of the atom bomb helps us to understand many of the mysteries that baffled Kulik.

There was no crater at Tunguska because the explosion had taken place above the ground, as is the case with an atomic bomb. The standing trees at the central point of the explosion confirmed this. At both Nagasaki and Hiroshima buildings directly beneath the blast remained standing, because the blast spread sideways. Genetic mutations in the flora and fauna around the Japanese cities resemble those witnessed in Siberia, while blisters found on dogs and reindeer in the Tunguska area can now be recognized as radiation burns.

Atomic explosions produce disturbances in the earth’s magnetic field, and even today the area around the Tunguska explosion has been described as being in “magnetic chaos.”

Professor Alexis Zolotov, leader of the 1959 expedition to Tunguska, calculated that, whatever the object was—a meteor or comet—it was about 130 feet in diameter, and exploded approximately 3 miles above the ground with a force of 40 megatons—2,000 times greater than the atomic bomb at Hiroshima.

(1947 to present)

The history of modern UFOlogy, or the study of unidentified flying objects, begins on June 24, 1947. That’s when Kenneth Arnold was flying his private plane near Mount Rainier in Washington State and saw nine shining disks moving against the background of the mountain. He estimated their speed at about 1,000 miles per hour and later said that the disks swerved in and out of the peaks of the Cascades with “flipping, erratic movements.” Arnold told a reporter that the objects moved as a saucer would “if you skipped it across the water.”

The next day Arnold’s story appeared in newspapers all over the United States. Soon reports flooded in of other “flying saucer” sightings, and the U.S. Air Force initiated an investigation, known as Project Sign. Ten days after the sighting, the air force announced confidently that Arnold had been hallucinating.

Then, on January 7, 1948, Captain Thomas Mantell—who was piloting a P-51 fighter jet, chased a round, white object in the sky. At 30,000 feet, Mantell seems to have blacked out and his plane went into a fatal dive. This episode probably did more than any other to publicize UFOs in the late 1940s.

Pilot Kenneth Arnold

Project Blue Book

Air force investigations of UFO sightings continued, and in 1952 Project Blue Book was born. Although this project lasted nearly 20 years and collected more than 12,600 reports of UFOs, its attitude throughout the life of the investigation remained skeptical. Project Blue Book dismissed all but 6 percent of the reports as explainable by natural causes. J. Allen Hynek, an astrophysicist asked to take part in the project, began as skeptic but became convinced that this residue of cases that could not be dismissed as hoaxes, illusions, or honest mistakes. “Blue Book,” says Hynek in The UFO Experience, “was a cover-up.”

It struck early students that Arnold’s UFO sighting was surely not the first-ever sighting of strange objects in the sky. A search of newspaper files revealed many older ones. As early as 1800 an “airship” was seen hovering over Baton Rouge. Charles Fort’s 1919 Book of the Damned devotes a chapter to reports of strange lights in the sky; these include the famous “False Lights of Durham,” seen over the city of Durham in northeast England in 1866. A commission headed by Admiral Collinson investigated the lights. Typically, it “reached no conclusion.”

One important feature of the sightings that later emerged was that the objects were often cigar-shaped, rather than circular; and the cigar-shaped objects were larger than the smaller saucers. In fact many observers have reported seeing the small saucers emerging from the cigar-shaped object, implying that this latter object is the parent craft.

Hynek was one of a small number of serious, responsible students of the UFO phenomenon who emerged in the early 1950s; others included Jacques Vallee, Donald Keyhoe, M. K. Jessup, and Aimé Michel. Keyhoe, who inaugurated his own study project, was convinced that beings from other planets who had been studying Earth for the past 200 years piloted the saucers. He and many others suggested that the first sighting occurred soon after the explosion of the first atomic bomb.

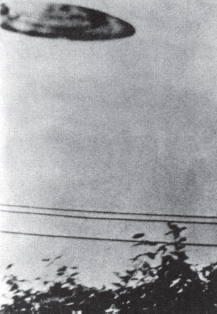

From the files of Project Blue Book: a 15-year-old boy shot this photo of a UFO flying over his San Bernadino, California, home in the 1950s.

The Roswell Incident is one of the most hotly disputed stories in UFO mythology. On a July evening in 1947, a fast-moving, glowing object hurtled through the sky above ranch foreman Mac Brazel as he rode out to check his sheep. The object seemed to crash, and the following day Brazel found shiny metal foil and wreckage in a desert area north of Roswell, New Mexico. The U.S. Air Force soon moved in and removed the debris, then announced that it had been merely a crashed weather balloon. This caused widespread incredulity, and rumors spread that an alien spaceship had crashed and been seized by the government.

A sign marks the UFO crash site near Roswell, New Mexico, and also advertises the UFO Museum in Roswell. The area has become famous as the nexus of UFOlgists.

A Biblical Basis?

Josef F. Blumrich, a NASA engineer, was intrigued by Erich von Daniken’s assertion that Ezekiel, in the Bible’s Book of Ezekiel, had described something very like a spaceship (“a great cloud, with brightness round about it, and fire flashing forth continually, and in the midst of the fire, as it were gleaming bronze.”). Blumrich made a careful study of the passage and concluded that Ezekiel’s description is remarkably like that of a spaceship.

But Where Did They Come From?

Renowned British astrologer Sir Fred Hoyle claimed that the saucers had been around since the beginning of time. This view is taken by Raymond Drake as well, whose books Gods and Spacemen in the Ancient East and Gods and Spacemen in the Ancient West, examine ancient texts for mentions of objects that sound like Ezekiel’s wheel of fire.

Some writers are convinced that UFOs are hostile. Their view is that sightings are of reconnaissance vehicles preparing an invasion of Earth. Others, including noted UFOlogist Brinsley Le Poer Trench, believe that there could be two groups of “sky people,” one very ancient and friendly, the other more recent and sinister in its intentions. The “antis” like to point out that car engines and other electrical equipment seem to stall in the presence of UFOs—one writer blames them for the massive New York power failure of 1965.

Inevitably some of the speculation seems to cross the line into pure fantasy. For instance Frank Scully, a Hollywood journalist who wrote for the magazine Variety, suggested that the saucers came from Venus and were driven by magnetic propulsion (a book he wrote was later denounced as a hoax by True magazine). UFO researcher George Adamski claimed he had shaken hands with a charming Venusian in the California desert and was taken for a trip into space. Antonio Boas, a Brazilian farmer, claims that he was taken aboard a saucer where two “little men” took blood samples, and a beautiful naked “girl” with no lips seduced him—obviously for scientific purposes. Adamski himself states that most “contactee” claims are pure fantasy—giving precise figures of 800 “genuine” cases out of 3,000.

Many contactees have reported hearing the voices of spacemen inside their heads. Dr. George Hunt Williamson’s Secret Places of the Lion describes how spacemen contacted him through automatic writing, telling him they arrived on Earth 8 million years ago and built the Great Pyramid 24,000 years ago; a spacecraft is hidden under its base, according to Williamson.

As UFO reports continue, many from ordinary people with no desire for publicity, there has been increasing acceptance of the phenomena. Carl Jung, who began by advancing a theory that the saucers were “projections” from the collective unconscious, ended by recognizing that the saucers seemed to be more “factual” than that. In 1969 Air Marshal Sir Victor Goddard lectured in London and suggested that UFOs could come from a parallel world; this view has become increasingly popular.

The famous Lubbock Lights UFO incident. During August 1951, on at least 14 occasions, lights hovered over the town of Lubbock, Texas. Hundreds of witnesses saw them, including four respected college professors: a geologist, a chemist, a physicist, and a petroleum engineer. Four photographs of the lights exist. Project Blue Book proclaimed that there was a perfectly natural explanation for the lights—but it never revealed what that “natural” cause was.

Collective Memories and Lines of Energy

Many writers have pointed out that UFOs are seen most frequently at the crossing point of ley lines (lines where Earth’s energy is allegedly concentrated). For example, there have been hundreds of sightings over Warminster, in the United Kingdom. In fact an entire book, The Warminster Mystery by Arthur Shuttlewood, published in 1973, is devoted to those sightings. Shuttlewood’s book, like John Michell’s 1969 book The Flying Saucer Vision, points out the association between UFO sightings and ancient sacred sites. In the 1973 book The Dragon and the Disc, F. W. Holiday notes the similarity between the shape of disc barrows—Bronze-Age burial mounds that are common in Wiltshire in the United Kingdom—and saucers. He also suggests how frequently UFO sightings are associated with “ghosts”—as when a blood-soaked figure staggered out of a hedge near Warminster and vanished. In his 1978 book, The Undiscovered Country, Stephen Jenkins conducts a lengthy and highly convincing investigation into the connection between UFOs, ley lines, and supernatural occurrences. Holiday, too, believes that saucers, like lake monsters, should be regarded as some kind of partly supernatural phenomenon, associated with racial memory, as it is called by Jung.

UFO crash simulation. Perhaps an alien craft will someday crash on Earth—and finally provide irrefutable evidence of extraterrestrial life.

One of the most striking elements of UFOs is the ambiguity of the whole phenomenon. The evidence looks very convincing; yet all hopes of reaching some final, positive conclusion recede when we try to pin it down. Case in point: medical and parapsychological researcher Andrija Puharich describes how psychic Uri Geller went periodically into trances. In these trances, voices of “extraterrestrials” spoke through his mouth, identifying themselves as members of “The Nine,” a group of space people whose aim, they said, was to guide the Earth through a difficult period in its history and prevent humankind from destroying itself. There is much solid evidence that the phenomena really took place, and Puharich himself is a highly regarded scientific investigator; yet the events seem so weird and inconsequential that it is difficult to take them seriously. Puharich broke with Geller, and afterward the communications continued, as recounted by Stuart Holroyd in his 1977 book Prelude to a Landing on Planet Earth. The “alien communicators” declared that they intended to land on Earth in force and were eager to prepare humankind for this event . . . but the date for the landing passed without incident. John Keel, another investigator of UFO phenomena, speaks a great deal about the “men in black” who often warn people to keep silent about their glimpses of UFOs. His books are full of “hard evidence,” including names, dates, and signed statements. It seems clear that something is going on, but whether that something is contact with extraterrestrial intelligence seems doubtful.

In The Invisible College, published in 1975, Jacques Vallee suggested that the phenomena may be basically “heuristic,” that is, intending to educate the human race about a new consciousness. He points out that it is impossible to decide whether UFOs are genuine and, if they are genuine, where they originate: in outer space, in other dimensions, or in the human mind itself. Yet the repetitiveness of the phenomenon and its unpredictability seem to prepare the human mind for something startling; or, at the very least, to remain open-minded. Alternatively, it could be a manifestation of right-brained human unconscious trying to prevent us from becoming jammed in a two-dimensional left-brain reality.

Are They Out There?

By the end of the 1970s much of the public curiosity about UFOs had dissipated, but research into the phenomenon continues. In France SEPRA (Service of Expertise on Atmospheric Phenomena) was set up in 1983 to officially study UFOs. After the organization folded in 2004, its head, Jean-Jacques Velasco, published UFOs . . . the Evidence, in which he states unambiguously that UFOs do exist. In fact of the approximately 5,800 cases SEPTRA studied, Velasco reports that at least 14 percent were extraterrestrial in origin.

A model of an alien that was allegedly autopsied by the U.S. government after the 1947 Roswell, New Mexico, incident. If UFOs are real, one must conclude that extraterrestrial beings, the creators and operators of the UFOs, also exist.

(1953 to present)

Have you been abducted by aliens? The question is less absurd than it sounds, for there are thousands of people who believe they have been taken to alien spacecraft but had their memories tampered with so that they no longer recall what happened.

In 1989 the late John Mack, a psychiatrist and professor at Boston University, had been asked by a psychiatrist friend if he would like to meet Budd Hopkins. Mack asked, “Who’s he?” When told that Hopkins was a New York artist who tried to help people who believed they had been taken into spaceships, Mack replied that Hopkins must be crazy, and so must the “abductees.”

But Mack was a reasonable, open-minded sort of person, and a few months later he agreed to meet Hopkins. And Mack learned, to his amazement, that all over the United States there are people who claim that they have been taken from their beds by little gray-skinned aliens with huge black eyes, transported aboard a UFO, subjected to medical examination, and then released with the memory of the experience obliterated. But under hypnosis, they could frequently recall the experience in great detail.

Are they trying to contact us?

Is It Mental Illness?

Mack’s natural suspicion was that their “memories” of the abduction were somehow implanted by the leading questions asked by the hypnotist. He also suspected that such people were neurotics who needed some drama to brighten their lives, and that they had probably derived their ideas about little gray aliens from television or books like Whitley Strieber’s 1987 best-seller Communion. But when he met some of the abductees, he was struck by their normality; none of them seemed psychiatrically disturbed. Moreover a large percentage of these people had no previous knowledge about abductees and little gray men. There was an interesting sameness about their descriptions of the inside of the spacecraft, their captors, and what happened to them. Clearly they were telling what they felt to be the truth.

When Hopkins suggested that he should refer cases from the Boston area to Mack, Mack agreed. Between spring 1990 and the publication of Abduction four years later, Mack saw more than 100 “abductees” who ranged in age from 2 to 57. They came from every group of society: students, housewives, writers, business people, computer industry professionals, musicians, even psychologists.

Dr. John Mack, perhaps more than anyone else, lent credibility to stories of alien abductions.

A typical case was that of Catherine, a 22-year-old music student and nightclub receptionist. One night in February 1991, she suddenly decided to go for a drive after working at the nightclub. When she arrived home, she was puzzled to discover that it was so late: 45 minutes seemed to be missing. She was also suffering from a nosebleed—the first in her life. The next day she saw on television that a UFO had been seen in the Boston area. Someone recommended that she see John Mack.

After several sessions of hypnosis, memories of abduction began spontaneously to emerge. She recalled that her first abduction had occurred when she was 3, and another when she was 7. Finally she recalled what had happened in the missing three-quarters of an hour. She had found herself driving into some woodland, where she experienced a kind of paralysis. Aliens took her out of her car and guided her into a UFO, where her abductors began to remove her clothes. When she asked them angrily why they didn’t just rent some pornography, they looked blank, and it dawned on her that they didn’t know what pornography was.

Her abductors took her into an enormous room in which there were many tables upon which were lying human beings. She was made to lie on a table, and an instrument was inserted into her vagina. When the instrument was removed, there was, on the end of it, what seemed to be a three-month-old fetus. (Three months earlier, she had found herself driving along deserted roads in the middle of the night. She pulled in at a rest stop and, although she had no further memory of what happened, she believes she may have been impregnated at that time and that the aliens may have been engaged in some kind of breeding experiments.

Her attitude toward the aliens was at this time one of rage, but, during the course of the sessions with Mack, she came to take a more balanced view, suspecting that the aliens may be “more advanced spiritually and emotionally than we are.” She finally became one of the most active members of Mack’s support group, reassuring others who found the abductee experience terrifying.

A Compelling Story

If some abduction tales sound wildly implausible, others are oddly convincing. In September 1961 Betty and Barney Hill were driving to their New Hampshire home from Canada when they spotted a UFO. Both of them blacked out and, two hours later, woke up in the car. Under hypnosis, both recalled being taken aboard a “saucer” where they were examined. John G. Fuller’s book about their experience, The Interrupted Journey, is one of the more convincing contactee records and includes precise transcripts of hypnotic sessions.

Betty and Barney Hill of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, above, claimed that on a trip home from Canada in 1961 they were abducted and held aboard a UFO.

We might conclude from all these abductions that the Earth may be in some imminent danger to which we all must be immediately awakened. But Mack’s view was that the abduction experience “opens the consciousness” of those concerned, and that his own experience of working with abductees “provides a rich body of evidence to support the idea that the cosmos, far from being devoid of meaning and intelligence, is informed by some kind of universal intelligence, one to which human intelligence is akin and in which it can participate.”

Coverage in the Press

In December 2005 a couple from Houston, Texas, said that they were abducted by aliens on more than one occasion. Clayton Lee claimed to have been probed by the aliens, which took some of his DNA and left him with a scar on his side. Donna Lee contended that the aliens also removed a fetus from her body. A local television station broadcast a session that Donna Lee had with a hypnotist who was trying to help her retrieve memories of the incident. During the session Lee became upset, screaming, “They’re touching me! Quit touching me!”

This was not the first, nor would it be the last time alien abductions were explored on television. Several documentaries, including one broadcast on the highly regarded science show NOVA, which included interviews with Carl Sagan and John Mack.

Common Threads

If alien abductions are nothing more than hokum, then why do the abductees’ personal accounts share so many common elements? In a 1998 article in Skeptical Inquirer magazine, psychologist Dr. Susan Blackmore discussed some of those shared attributes:

The experience begins most often when the person is at home in bed (Wright 1994) and most often at night (Spanos, Cross, Dickson, and DuBreuil 1993). . . . There is an intense blue or white light, a buzzing or humming sound, anxiety or fear, and the sense of an unexplained presence. A craft with flashing lights is seen and the person is transported or “floated” into it. Once inside the craft, the person may be subjected to various medical procedures, often involving the removal of eggs or sperm and the implantation of a small object in the nose or elsewhere. Communication with the aliens is usually by telepathy. The abductee feels helpless and is often restrained, or partially or completely paralyzed.

What could explain these shared experiences?

Nearly every abductee who has recall of the abduction has described a similar experience, including seeing a blindingly intense light and feeling afraid before being transported to the alien spacecraft for seemingly biological experimentation.

In her 2005 book, Abducted: How People Come to Believe They Were Kidnapped by Aliens, psychologist Dr. Susan Clancy argues that the abduction memories actually come from our popular culture—television shows, movies, comic books, newspapers. In addition she explains that alien abduction stories began to emerge only after such stories were featured on television and in movies, starting in about 1953.

Dr. Susan Clancy, a Harvard University psychologist, interviewed many people who claimed to have been abducted by aliens and concludes that their experiences are not real.

How Many?

Unlike the UFO issue—which most feel does not really concern nonbelievers—the idea of abduction has all the signs of being something that should concern everyone. A poll conducted over three months by the Roper organization in 1991 indicated that hundreds of thousands of Americans believed they had undergone the abduction experience.

Sleep Paralysis

Some researchers of abduction incidents posit that people who have claimed to have been abducted by aliens were actually suffering from a condition called sleep paralysis, a state in which a person is awake and can see and hear, but cannot move. Sleep paralysis is common among those suffering from narcolepsy—a condition in which a person falls asleep unexpectedly and uncontrollably. The paralysis can trigger anxiety, fear, and even hallucinations in which the sufferer feels that someone is in the room with them.

Take the Survey

For those who suspect that they may have been abducted, the Web site of the Alien Abduction Experience and Research Organization offers an online quiz. Here are just a few of the 25 questions: Do you secretly feel you are special or chosen? Do you dream about seeing UFOs, being inside UFOs, or interacting with UFO occupants? Have x-rays or other procedures revealed unexplainable foreign objects lodged in your body?

(1970s to present)

In 1979 Barbara Herbert, a 39-year-old woman from Dover, England, approached social worker John Stroud for help in searching for her twin sister. Their mother had abandoned the girls at the beginning of World War II, and they had been separately adopted. With John Stroud’s help, she traced the midwife who had delivered them. Eventually Herbert learned that her twin was named Daphne Goodship and lived in Wakefield, Yorkshire.

When Barbara and Daphne finally met, both were wearing a beige dress and a brown velvet jacket. This proved to be merely the first of an astonishing series of coincidences. Both women were local government workers, as were their husbands; both had met their husbands at a dance at the age of 16 and married in their early 20s in the autumn; both had suffered miscarriages with their first baby, and then had two boys followed by a girl; both had fallen downstairs at the age of 15 and suffered from weak ankles as a result; both had taken lessons in ballroom dancing; and both had the same favorite authors. Altogether, John Stroud listed 30 coincidences of this sort. Some of them were likely due to identical genetic predispositions. But accidents like falling downstairs or miscarriages could hardly be explained by their genes.

Identical twins

The Jim Twins

Around the same time, a pair of identical male twins appeared on The Johnny Carson Show. When Jim Lewis of Lima, Ohio, was nine years old, he discovered that he had an identical twin who had been adopted at birth. Thirty years later, he set out to find him and learned his twin, Jim Springer, lived in Dayton, Ohio. As soon as they met, they discovered a string of the same kind of preposterous coincidences that had amazed Barbara and Daphne.

Both had been named Jim; both had married a girl named Linda, then divorced and married a girl named Betty; both had called their sons James Allan, although Lewis spelled the name with only one “l”; both had owned dogs named Toy; both had worked part-time as deputy sheriffs; both had worked for McDonald’s and as gas-station attendants; both spent their holidays at the same seaside resort in Florida and used the same beach—a mere 300 yards long; both drove a Chevrolet; both had a tree in the garden with a white bench around it; both had basement workshops where they built frames and furniture; both had had vasectomies; both drank the same beer and chain-smoked the same cigarettes; both had gained 10 pounds at the same point in their teens, and lost it again; and finally, both enjoyed stock-car racing but disliked baseball.

Their case was published in Science, the journal of the American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Not Clones

A clone has identical DNA to its original, but recent studies have revealed that identical twins do not share identical genes or DNA.

Professor Tim Bouchard, a psychologist who had been studying twins at the University of Minnesota, was so fascinated by the Jim twins that he raised a grant to study identical twins separated at birth. John Stroud soon heard about his research, and sent some of his identical twins to America. (John Stroud and Tim Bouchard acquired the same number of identical twins to study—sixteen pairs.) Bouchard quickly realized that the coincidences in the lives of the “Jim twins” were the rule, rather than the exception.

The “Jim twins,” James Lewis, left and James Springer, right, with Professor Tom Bouchard at the University of Minnesota. After they were reunited in 1979, at the age of 29, the twins agreed to take part in a research study on the environment’s effect on development.

Deep Connection

Recent research provides more fodder for speculation about the bond between identical twins. For instance, identical twins who grew up separately have similar IQs, even closer (on average) than those of fraternal twins who grow up together. When one of a pair of identical twins dies, the remaining twin often experiences deep survivor’s guilt and prolonged grief. They may also have difficulties in forming intimate relationships. The kind of suffering felt by surviving twins is so specific that in 1986, Florida therapist Michael Caruso formed a support group called Twinless Twins.

The Power of Twins

Twins have always been a part of myth and legend. Greek and Roman mythology gave us several sets of twins: Castor and Pollux were Greek gods who aided shipwrecked sailors. Their names were also given to the twin stars in constellation Gemini. In Roman mythology, twin brothers Romulus and Remus—sons of Mars, god of war—founded Rome.

Destinies in Duplicate?