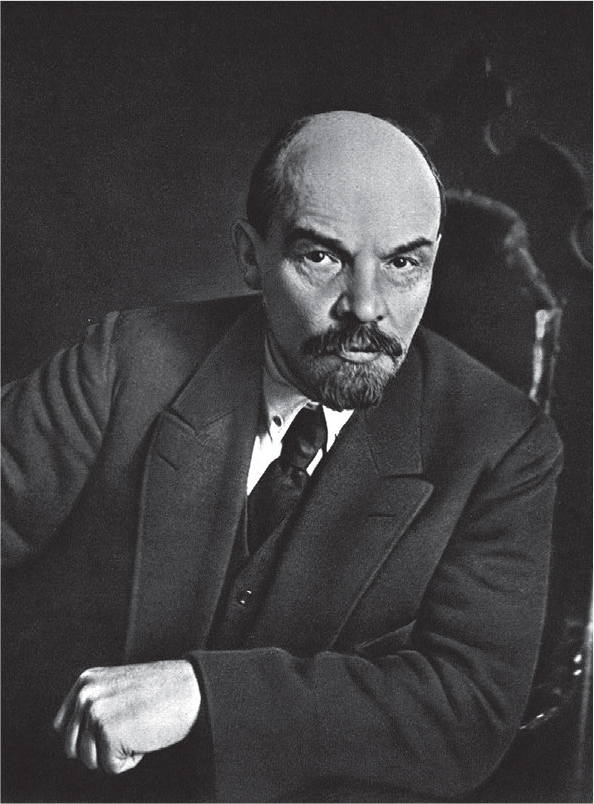

Vladimir Lenin

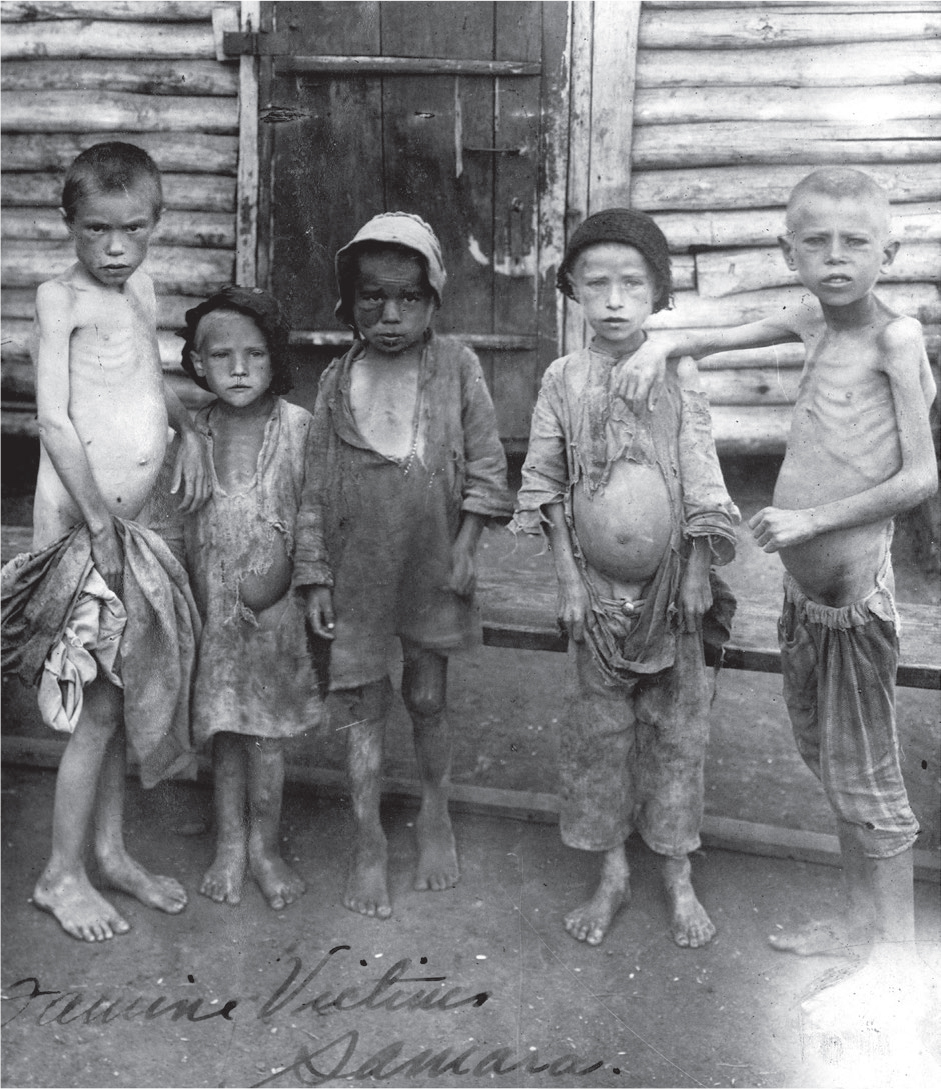

THE RAINS DIDN’T COME IN THE SPRING OF 1920. It was unusually hot, and by planting season the ground had been baked hard. The dry weather carried on throughout the summer and into the autumn. The harvests proved small. That winter saw scant snow covering the land, followed by a second parched spring. The worst drought in thirty years gripped much of Soviet Russia in its deadly grasp: nearly the entire length of the Volga River Basin, from Nizhny-Novgorod in the north all the way to the Caspian Sea in the south, and from Ukraine in the west to the edge of the Ural Mountains in Asia. Villages were starving. Over a hundred thousand peasants left their homes in search of food. Russia was facing a catastrophe.

Life for the Russian peasant had never been easy, even after the end of serfdom in 1861. The peasants eked out a meager existence not much beyond subsistence levels. Farming methods were primitive, the land was overcrowded, taxes were heavy. In the late 1880s, the Russian state began a massive program of industrialization, to be financed by the sale of grain abroad. Ne doedim, no vyvezem—we may not eat enough, but we’ll export—became the motto of the effort to bring tsarist Russia up to the modern lifestyle of the West. Tax collectors were sent out into the countryside to redouble their efforts; peasant farmers were forced to hand over an ever larger share of their rye, wheat, and barley. Between 1881 and 1890, the average yearly export of major grains almost doubled.

And then, in the late summer of 1891, the crops failed following a horrendous drought. Peasants ran out of food and survived on what they called goly khleb, hunger bread: an odious loaf made from a small dose of flour mixed with some sort of food substitute, usually lebeda—saltbush or orache—that when consumed for any length of time causes serious illness. By December, the Ministry of the Interior estimated more than ten million people would need government relief. Leo Tolstoy, the conscience of the nation, publicized the extent of the famine and organized relief, thus helping to let the world know of the full scale of the disaster. America was among the countries to come to Russia’s aid. A group of Minnesotans sent a ship full of Midwestern grain that was greeted by fireworks and a jubilant crowd when it arrived at the Baltic port of Libau* in March 1892. In the end, the people of Minnesota donated over 5.4 million pounds of flour and $26,000 worth of supplies to combat the famine on the other side of the globe. The generosity of the Americans was commemorated by the artist Ivan Aivazovsky, the great master of Romantic seascapes, in two paintings that he himself delivered to America in 1893 along with other gifts of thanks from Tsar Alexander III. The paintings hung for decades in the Corcoran Gallery until First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy saw them and had them moved to the White House.

The Russian government mounted its own relief effort, which, though bedeviled by setbacks and inefficiencies, at its peak provided more than eleven million people with supplemental food. The state was joined in its efforts by a great many in educated society. Moved by the plight of the hungry masses, Anna Ulyanova, a twenty-seven-year-old nobleman’s daughter from the town of Simbirsk on the Volga River, distributed food and medicine to the needy, like so many others of her background. Her brother Vladimir, however, was an exception. Not only did he refuse to aid the suffering, he welcomed the famine, since he believed it would help destroy the people’s faith in God and the tsar. Revolution, not charity, would save the peasants, he said. “The overthrow of the tsarist monarchy, this bulwark of the landowners, is their only hope for some sort of decent life, for an escape from hunger, from unending poverty.” Vladimir, better known as Lenin, his revolutionary nom de guerre, understood even as a young man the connection between food and power.

Vladimir Lenin

Russia in 1921 was confronting more than a drought. Indeed, the lack of rain played only a secondary role in the famine. Much more important had been seven years of war and revolution. By the end of 1916, after two years of brutal fighting in the First World War, Russia was experiencing grain shortages and bread riots in major cities. In February 1917, factory women protesting the high cost and lack of bread in the capital of Petrograd sparked the revolution that led to the fall of the tsarist regime the next month. The food crisis and the state’s inability to address it had been directly responsible for the death of the three-hundred-year-old Romanov dynasty.

After overthrowing the interim Provisional Government in October, the Bolsheviks set about establishing a monopoly of power, arresting and killing their political opponents. Their actions plunged Russia into a civil war of unspeakable barbarism that would last several years. Foreign forces—including the British, French, Americans, and Japanese—landed on Russian territory, first in the hope of keeping Russia in the war against Germany, and then offering nominal support to the White armies fighting against the Bolshevik Red Army. Complicating matters still further, Great Britain’s Royal Navy established a blockade in the Baltic Sea that isolated the new Soviet government from the West for many months.

The Bolsheviks knew from the start that bread was crucial to their survival. If they didn’t solve the food problem, the revolution would fail. Leon Trotsky, the great revolutionary and prominent Soviet official who, among other things, was then head of the Extraordinary Commission for Food and Transport, told the Central Executive Committee of the Soviets in April 1918: “I say it quite openly; we are now at war, and it is only with guns that we will get the grain we need. Our only choice now is civil war. Civil war is the struggle for bread [. . .] Long live the civil war!” A key tactic in the effort to seize the grain was to stoke class warfare in the villages. The Bolsheviks created Committees of Poor Peasants (Kombedy) to confiscate the grain of the wealthier peasants, the so-called kulaks, and hand it over to the state. Often composed of outsiders, the Kombedy terrorized the local population, stealing their personal property, making summary arrests, and further destabilizing rural life, an effort Lenin endorsed as part of a larger goal of destroying age-old and, in his eyes, backward peasant culture. A Provisioning Army (Prodovol’stvennaya armiya or Prodarmiya), consisting largely of unemployed Petrograd workers, was also created and sent out into the countryside, both to spread Bolshevik propaganda and to help in the requisitioning of grain. Fyodor Dan, a leader of the Menshevik Party,* called it “a crusade against the peasantry.”

Lenin, however, was only getting started. In August 1918, he ordered that wealthy peasants be taken hostage and executed should the requisition targets not be met. He sent this directive to the Penza Soviet:

The kulak uprising in your five districts must be crushed without pity [. . .] You must make an example of these people. (1) Hang (I mean hang publicly, so that people see it) at least 100 kulaks, rich bastards, and known bloodsuckers. (2) Publish their names. (3) Seize all their grain. (4) Single out the hostages per my instructions [. . .] Do all this so that for miles around people see it all, understand it, tremble.

Even fellow Bolsheviks were aghast at what was being done to the peasants. “The measures of extraction are reminiscent of a medieval inquisition,” commented one official after witnessing a requisition brigade at work in southern Russia. “They make the peasants strip and kneel on the ground, whip or beat them, sometimes kill them.” In June 1918, Joseph Stalin traveled to Tsaritsyn* with two armored trains carrying 450 Red Army soldiers to secure food for the capital. His initial success was not enough for Lenin, who felt Stalin had been soft and ordered him to “be merciless” toward their enemies in the hunt for food. “Be assured our hand will not tremble,” Stalin replied. “We won’t show mercy to anyone [. . .] We will bring you bread.”

The grain quota established by the central government grew ever higher. By 1920, it had risen from eighteen to twenty-seven million poods.* The peasants called that year’s requisition campaign “The Iron Broom,” for it swept the villages clean of practically every last kernel of grain, leaving the peasants with almost nothing. Local authorities could not believe what they were seeing and sent back reports to their bosses in Moscow that such actions were “senseless and futile.” Even though the war against the White armies had largely ended with the defeat of General Pyotr Wrangel’s forces in late 1920, still the campaigns against the peasants raged on.

Peasants responded to the brutal policies of the Bolsheviks in a number of ways. One was to hide their grain, be it under the floor, down the well, stuffed in thatched roofs, or behind fake walls and secret compartments in their huts. The men of the Prodarmiya soon caught on to the peasants’ tricks and became relentless in ferreting out their hidden stores, regardless of the damage they caused. A second response was to reduce the land under cultivation and grow only the bare minimum necessary for their own survival, thus denying any surplus for the state. Between 1917 and 1921, as much as a third of the arable land in the main agricultural regions of Russia was removed from production. The harvest of 1920 was just barely over half that of 1913.

And some peasants decided to fight back. Revolts against grain requisitioning first erupted in the summer of 1918 and grew as time went on. The uprisings turned into an actual war in the summer of 1920, when a former factory worker and schoolteacher by the name of Alexander Antonov organized the Partisan Army of the Tambov region. Eventually growing to some fifty thousand men, many of them Red Army deserters, Antonov’s peasant army swept out of Tambov and soon spread into the lower Volga region—Samara, Saratov, Tsaritsyn, and Astrakhan—and even into western Siberia. “Banditry has overwhelmed the whole province,” wrote terrified Bolshevik leaders in Saratov in a telegram to Moscow. “The peasants have seized all the stocks—3 million poods—from the grain stores. They are heavily armed, thanks to all the rifles from the deserters. Whole units of the Red Army have simply vanished.” The fire of revolt seemed unstoppable, and the Soviet government was losing control over ever more territory.

Toward the end of 1920, the Cheka—the Soviet political police, precursor to the KGB—admitted that, except for areas around Moscow, Petrograd, and the Russian north, the entire country was convulsed with unrest. The situation grew worse in early 1921. The chairman of the Samara Province Cheka wrote to his superiors in Moscow in a top-secret memorandum: “The masses now have a hostile attitude to the communists [. . .] Cholera and scurvy are raging [. . .] Desertions from the garrison are growing.” Lenin was beside himself. The peasant war, he warned his colleagues, was “far more dangerous to us than all the Denikins, Kolchaks, and Yudeniches put together.”* The key to the fate of the Soviet government, in other words, lay with the country’s rebellious peasants.

And it wasn’t just the peasants. The Bolsheviks began to lose support in the cities, too, among workers and soldiers, once their most devoted followers. In January 1921, bread rations were cut by as much as 30 percent in a number of cities. Angry and hungry, the workers of Petrograd went on strike. Demonstrations quickly devolved into riots. Cheka detachments had to be dispatched to restore order; martial law was declared in late February 1921. The following month, the sailors at the Kronstadt naval base rebelled against what they called the “Communist autocracy,” characterizing the country’s rulers as “worse than [Tsar] Nicholas” and issuing a call for their own “third revolution.” Lenin saw to it that the mutiny was crushed. Over two thousand men were sentenced to death, more than six thousand sent off to prison.

To save the regime, Lenin announced at the Tenth Party Congress in March a strategic retreat from the extremist policies of the past. “War Communism,” as the initial phase of the revolution came to be known, was to be replaced by the New Economic Policy (NEP), a concession to capitalism and market forces that allowed for private property and ownership of retail trade and small industry. Most important, NEP ended the forced grain requisitions in favor of a tax in kind (i.e., grain or other agricultural products). Henceforth, peasants would know exactly what their obligation to the state was, thus giving them the incentive to grow as much as possible, keeping any surplus for themselves.

Meanwhile, the war against Antonov’s peasant army raged on into the summer of 1921. An army of one hundred thousand led by General Mikhail Tukhachevsky mounted a campaign of ruthless terror that included the use of heavy artillery and airplanes against what the state called “bandits.” Soldiers were given orders to shoot on sight any person who refused to give his name. Families guilty of harboring bandits were to be arrested and deported from the province. Their property was to be seized, and their eldest son executed forthwith. Tukhachevsky’s army took thousands of hostages and interned them in kontsentratsionnye lageria—concentration camps. By August, ten camps in Tambov Province alone held over thirteen thousand prisoners. Lenin ordered his general to suffocate the enemy: “The forests where the bandits are hiding must be cleared with poison gas. Careful calculations must be made to ensure that the cloud of asphyxiating gas spreads throughout the forest and exterminates everything hidden there.”

Eventually, the Red Army gained the upper hand. Although Antonov would not be caught—and killed—until June 1922, the last of the rebels were being mopped up by the autumn of 1921.

The Bolsheviks, however, had vanquished one foe only to face another, much more dangerous one. In terms of sheer numbers, the famine of 1921 was the worst Europe had ever known. The Soviet government estimated that some thirty million people were facing death. The concessions to the peasants made in March at the party congress had come too late to alter the situation. Lenin had said then: “If there is a harvest, then everybody will hunger a little, and the government will be saved. Otherwise, since we cannot take anything from people who do not have the means of satisfying their own hunger, the government will perish.” Two years of drought, and several more of war and senseless cruelty, meant whatever harvest there might be would never come close to feeding a hungry Russia.

THE GOVERNMENT HAD been receiving reports of the growing crisis since the beginning of 1921. One Cheka report from January described the famine sweeping over Tambov Province, which it attributed to the “orgy” of requisitioning in 1920. The waves of refugees fleeing hunger throughout the Volga Basin became too large to ignore.

Yet that is just what the government did. Any official mention of the famine was forbidden until July 2, 1921, when the newspaper Pravda published the following notice on the back page: “This year the grain harvest will be lower than the average for the last decade.” It went on to add that there had been “a feeding problem on the agricultural front.” Orwellian language if ever there was. Ten days later, Pravda printed a fuller and more honest story that characterized the famine as “a catastrophe for all of Russia that is having an influence on every aspect of the country’s economic and political life.” It instructed readers in the famine zone to stay where they were and not to add to the “wave of refugees” or give in to the panic and rumors that represented such a “very large danger” to the country at present. The bourgeois West had been informed of the famine, Pravda went on, but it cautioned readers against placing any hope in the “capitalist predators,” who would not only be overjoyed to see the working people of Russia starve, but would use their suffering as a opportunity to organize a counterrevolution against the Soviet government.

A family of refugees in search of food

The West had indeed been made aware of the catastrophe early that month, in two separate appeals for help. One had been issued by Tikhon, patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, addressed to the pope, the archbishop of Canterbury, and other world religious leaders. The other had been made by the writer Maxim Gorky. Apparently, the idea had not belonged to Gorky, who was no great champion of the peasantry. (He even published a book the following year called The Russian Peasant in which he wrote of “the half-savage, stupid, and heavy people of the Russian villages” and expressed the hope that they would die out and be replaced by “a new tribe” of “literate, sensible, hearty people.”) Friends of the writer convinced him to use his considerable moral authority to speak with the Kremlin about issuing an open appeal to the world. Lenin, it seems, did not take much convincing.

In “To All Honest People,” dated July 13, Gorky wrote: “Gloomy days have come for the land of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Mendeleev, Pavlov, Mussorgsky, Glinka and other world-prized men [. . .] Russia’s misfortunes offer humanitarians a splendid opportunity to demonstrate the vitality of humanitarianism [. . .] I ask all honest European and American people for prompt aid to the Russian people. Give bread and medicine.” He included mention of the unprecedented drought afflicting his country, but said nothing about capitalist predators or counterrevolutionaries. Gorky sent the appeal initially to Fridtjof Nansen, the famous Norwegian explorer, scientist, and humanitarian, but Nansen replied that the Russians would be better advised to concentrate their efforts on the Americans, for they alone had the resources to help.

On July 22, 1921, a copy of Gorky’s appeal published in the American press landed on the desk of Herbert Hoover, the U.S. secretary of commerce. As soon as he had read it, Hoover knew what had to be done.

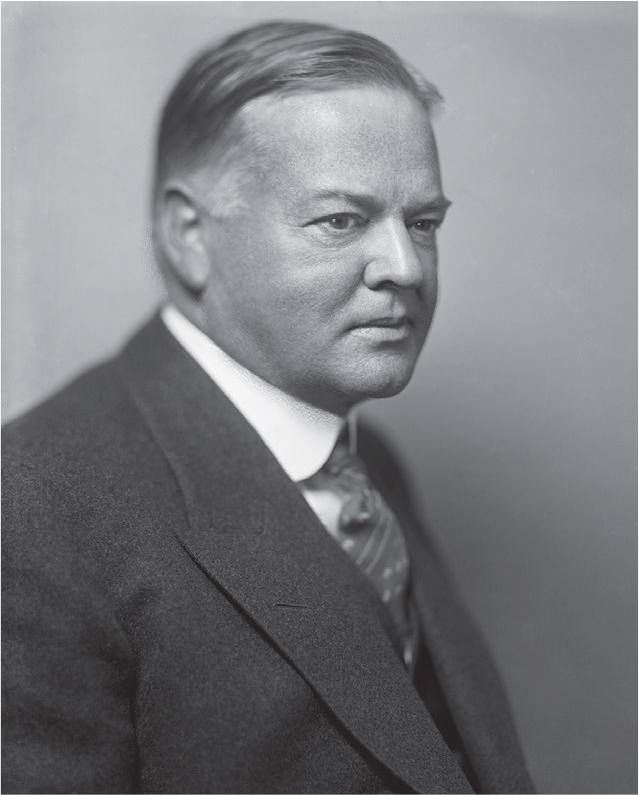

THE HUBERS LEFT THEIR NATIVE SWITZERLAND for the American colonies in the first half of the eighteenth century. At some point they anglicized their name to “Hoover” and abandoned the Lutheran Church for the Religious Society of Friends, the Quakers, drawn to the Friends’ revulsion to slavery. The family moved west with the young nation, eventually settling in a small cottage by Wapsinonoc Creek, in the rolling farm country of eastern Iowa. It was here, in August 1874, that Herbert Hoover was born.

Jesse Hoover was the blacksmith in the village of West Branch; Hulda, his wife, taught Sunday school and served as secretary in the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. They were simple, industrious folk. The family motto was “What matter if we descended from the highest unless we are something ourselves. Get busy.” Little Bertie, as he was called, was a sickly boy, often afflicted with the croup. Once, they thought he had died and laid him out on the table, a dime over each eye. Suddenly, Bertie stirred. “God has a great work for that boy to do,” said his amazed grandmother; “that is why he was brought back to life.” In 1880, Jesse died, followed by Hulda four years later. At the age of nine, Bertie became an orphan.

He was sent off to live with his uncle in Oregon. Life there was as serious as in his parents’ home. A fellow Quaker, Bertie’s uncle impressed upon the boy the importance of individual responsibility, hard work, and self-improvement. At school, Bertie was asked by his teacher to consider questions such as whether more men’s lives had been destroyed by liquor or by war. In 1888, Bertie, now just fourteen years old, was sent to Salem to be an office boy for the Oregon Land Company, where he acquired the fundamentals of business and proved an excellent worker. In 1891, he joined the inaugural incoming class at the new Leland Stanford Junior University, dedicated, in the words of its founder, “to promote the public welfare by exercising an influence in behalf of humanity and civilization.” When Hoover graduated four years later, with average grades and a B.A. in geology, none of his classmates held out any great hopes for his future. Yet the fundamental elements of his character that would make him a successful businessman and then a great humanitarian—a keen mind, boundless energy, a nascent sense of his uncommon talents, undeniable ambition, and a commitment to duty and service—were already in place.

Hoover set off to work as a mining engineer in the gold fields of the Australian outback (what he called “hell”) and then moved on to China, where he managed to put together what was perhaps the largest mining transaction in the country’s history, all before the age of thirty. He was in Tianjin in 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion. Refusing to be evacuated to safety, he delivered food and supplies on his bicycle to other members of the foreign settlement, with bullets whizzing past his ears. This marked young Hoover’s first relief mission, which, though modest, was not free of personal danger.

He was made a partner in the British engineering firm Bewick, Moreing and Company two years later and traveled about the world setting up and reorganizing mining operations in sixteen countries. He had a knack for making lackluster operations profitable and discovering new opportunities. In 1905, Hoover invested his own money into an abandoned mine in Burma, and under his management it quickly became one of the world’s richest sources of silver, zinc, and lead. He gained an international reputation for his administrative talent, technological understanding, and way with finances. After a few years, he parted company with the firm and went off on his own, operating simply as “Herbert C. Hoover,” with offices in New York, San Francisco, London, Paris, and St. Petersburg.

Hoover first visited Russia in 1909, and over the next several years he invested considerable time and money in the country. He was involved in oil fields around the Black Sea, copper mines in the Kazakh Steppes, gold and iron mines in the Ural Mountains. At one point, he was even asked to manage the Romanov Imperial Cabinet’s mines. He returned to Russia two years later to check on his investments. Although pleased with the state of his various operations, Hoover was disturbed by what he saw of Tsar Nicholas II’s Russia. He described as “hideous” the social tensions rumbling just beneath the surface. The sight of a chain gang being marched off into Siberian exile made him shudder. The brutality of the tsarist system haunted Hoover: he couldn’t shake the feeling that, in his words, “some day the country would blow up.” Hoover sold off his investments before the country exploded under the joint pressures of war and revolution. Russia, for Hoover, was a land filled with “annoyance and worry.”

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 found Hoover and his wife and children living in luxury in London. Forty years old, Hoover had amassed a fortune and now commanded the highest engineering fees in the world, but the fun had gone out of it. He retired from business. It appears that Hoover had undergone some sort of crisis. Money and worldly success were no longer enough for him; he wanted something different, something more. The old family values of doing good, being of service, aiding one’s fellow man pricked his conscience.

That year, Hoover was approached by the U.S. consul in Britain and asked to help Americans trapped in Europe by the war. Hoover set to work immediately and managed to arrange safe passage home for 120,000 people. Hoover’s career in public life had begun.

He next turned his attention to the crisis in Belgium. Ignoring its neighbor’s neutrality, Germany had invaded Belgium early in the war. In what became known as the Rape of Belgium, the German Army massacred thousands of civilians and burned their homes. The international outcry was enormous. With the country occupied by the Germans and cut off from supplies by a British naval blockade, the people of Belgium were soon running low on food. Mass starvation looked like a horrifying possibility.

Hoover set up the Commission for Relief in Belgium to bring food and supplies to the approximately nine million people living under German occupation in Belgium and northern France. But first he had to convince the warring nations to agree to his plan. The British, led by Minister of War Lord Kitchener, First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, and Prime Minister David Lloyd George, objected to the idea, fearful the Germans would take the food for themselves and thus prolong the war. Hoover, however, managed to convince them that the CRB’s agents would control the transport, storage, and distribution of all supplies, thus minimizing the possibility that the food would end up in German hands. At the same time, he also convinced both Britain and Germany that it was in their own best interest to allow the aid to go through, since this would go a long way to improving public opinion in America—still a neutral party—and so, perhaps, help to win the United States to their side in the conflict. Although no one in London or Berlin cared to listen to the arguments of some American businessman, in the end they all agreed.

For the next two and a half years, the CRB distributed over 2.5 million tons of food to the people of Belgium and northern France. There had never been an organization like it before. The CRB was the biggest, most ambitious relief effort in history, run by an outfit that was neither wholly private nor wholly public. One British Foreign Office official called it “a piratical state organized for benevolence.” It had its own fleet of ships, and even its own flag. The men of the CRB had been gathered from among Hoover’s business associates, Rhodes scholars, and U.S. Army officers, all of whom served with unquestioned devotion the man they called “The Chief.” His agents had complete freedom from the various European governments to operate as they saw fit, and their boss entrusted them with enormous leeway in their day-to-day operations.

At the same time, Hoover insisted on complete control over the entire operation. An undertaking of this size and complexity demanded the organizational skills of an exceptional businessman and the absolute power of a dictator. “Famine fighting is a gigantic economic and governmental operation handled by experts,” he insisted, “and not ‘welfare’ work of benevolently handing out food hit or miss to bread lines [. . .] Some individual with great powers must direct and coordinate all this.” “Some individual” meant, naturally, Hoover himself. With every minute of the day devoted to famine relief, Hoover had no time left to manage his personal financial affairs, but he didn’t worry. “Let the fortune go to hell,” he said. He wrung money out of everyone he could to support the CRB. He even managed to talk Britain and France into subsidizing his effort, to the tune of over $300 million. Not everyone was impressed by Hoover’s efforts. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts deemed the CRB a criminal act by an individual citizen who was usurping the authority of official United States diplomacy. He threatened an investigation.

Herbert Hoover

In the end, the CRB proved an enormous success. It disbursed over $880 million in aid, more than the typical annual budget of the United States government before the war, and saved millions of lives. “The Savior of Belgium,” as Hoover became known on both sides of the Atlantic, had won the admiration of people across Europe and America.

After the United States entered the war in April 1917, Hoover gave up his position at the CRB and returned home, where President Woodrow Wilson made him the head of the United States Food Administration established that summer. Dubbed “the food dictator” by the press, he was now in charge of the food chain for the entire nation. With singular focus, he pushed efficiency, standardization, and measurement to minimize waste. Every American learned to “Hooverize” for the sake of the war effort. At war’s end, Wilson invited Hoover to join him at the Paris Peace Conference as an unofficial adviser. To help sustain the hungry, war-torn continent and begin the process of economic reconstruction, Hoover urged the president to create the American Relief Administration, funded by a $100 million appropriation from Congress early in 1919. As its general director, Hoover undertook relief operations in thirty-two countries, not only offering food and clothing but rebuilding devastated infrastructure and acting as a quasi-intelligence and diplomatic organization for the Allied powers. Upon learning that Europe’s telephone and telegraph systems had been largely destroyed, Hoover created an effective wireless network using U.S. Navy vessels and experts from the Army Signal Corps. Nothing would stand in the way of accomplishing the mission. Over the course of nine months, the ARA distributed over $1 billion in aid.

The establishment of the ARA symbolized the arrival of the United States on the international stage. Its creation was an expression of Americans’ growing confidence in their ability to project American power and values around the globe. Hoover shared Wilson’s belief in America’s mission to improve the world. Yet, unlike the president, whose practical knowledge of life abroad was quite limited, Hoover had lived outside the United States for many years and so had a much better understanding of the world and how difficult improving it was going to be.

Wilson, like many presidents after him, mistakenly believed America could redeem humanity; a wiser, more knowledgeable Hoover was content to ease its suffering. “The sole object of relief,” Hoover remarked in December 1918, “should be humanity. It should have no other political objective or aim other than the maintenance of life and order.”

That said, he was convinced that neither life nor order could be secured in nations that fell to the new threat: Bolshevism. He made it clear in a memorandum in November 1918 that the first order of business in the reconstruction of Europe was the need “to stem the tide of Bolshevism,” which could only be achieved through the peace and stability that adequate food made possible. Wilson agreed, writing to the chairman of the House Appropriations Committee in early 1919: “Bolshevism is steadily advancing westward, is poisoning Germany. It cannot be stopped by force, but it can be stopped by food.” Food, the two men correctly understood, was a weapon.

Many in the United States, intent on “making the Hun pay” for the war, were not so clear-sighted. The U.S. Senate went out of its way to forbid the use of any of the appropriation for the ARA in the defeated enemy states. Hoover had fought against the restriction, and had also spoken out against the Versailles Treaty’s harsh treatment of Germany. Forcing the Germans to accept the blame for the war and to pay punitive reparations, the treaty, in his opinion, reeked of “hate and revenge” and was bound to lead to resentment and political instability. Not to be stymied by the small minds of the Senate, Hoover outwitted his own government by moving aid through a byzantine network of organizations, thus making it impossible to follow exactly what the ARA was up to. In the end, Hoover managed to direct over 40 percent of the ARA’s relief supplies to Germany and the former Austro-Hungarian Empire.

The economist John Maynard Keynes, representative of the British Treasury to the peace talks, stood in awe of Hoover and the ARA:

Never was a nobler work of disinterested goodwill carried through with more tenacity and sincerity and skill, and with less thanks either asked or given. The ungrateful Governments of Europe owe much more to the statesmanship and insight of Mr. Hoover and his band of American workers than they have yet appreciated or will ever acknowledge [. . .] It was their efforts, their energy, and the American resources placed by the President at their disposal, often acting in the teeth of European obstruction, which not only saved an immense amount of human suffering, but averted a widespread breakdown of the European system.

Keynes and Hoover, who met at the conference, were of the same mind about the treaty. Keynes was convinced that had there been more diplomats in possession of Hoover’s “knowledge, magnanimity, and disinterestedness,” they would have been able to secure “the Good Peace.”

ALTHOUGH HOOVER UNDERSTOOD how Bolshevism spoke to the Russian people after centuries of oppression, he was an unbending foe of communism, and would remain so for his entire life. He was against official recognition of Lenin’s Soviet state, what he called “this murderous tyranny,” not only since he believed this would encourage radicalism in the West, but also given the Soviets’ refusal to assume tsarist debts* and his conviction that the Bolsheviks would never protect American lives or property—views shared by Wilson.

Nevertheless, Hoover did not support military action by the United States. He wrote in a memorandum to Wilson on March 28, 1919: “No greater fortune can come to this world than that these foolish ideas should have an opportunity somewhere of bankrupting themselves.” In the meantime, however, he was not against offering aid to those then waging war against Lenin and the new Soviet Russia. He wrote Secretary of State Robert Lansing from Paris in August 1919 that the ARA should support the White Army forces of General Nikolai Yudenich, convinced that the Whites represented Russia’s best hope for a constitutional government and the defense of personal liberty. When Yudenich marched on Petrograd in the autumn, Hoover supplied him with food, clothing, and gasoline. The grateful general wrote to thank “Mr. Hoover, Food-Dictator of Europe,” and informed him that his army was “now existing practically upon American flour and bacon,” which was no less important for their success than “ rifles and ammunition.”

Hoover later tried to cover up his support of the Whites, but Lenin and the rest of the Soviet leadership knew about it. Understandably, the true motives of America’s great humanitarian remained under a cloud of suspicion.

AFTER READING GORKY’S appeal on July 22, 1921, Hoover, now secretary of commerce under the new president, Warren G. Harding, wrote to Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes: “I feel very deeply that we should go to the assistance of the children and also provide some medical relief generally.” He stated that he wished to reply to Gorky’s appeal. “I believe it is a humane obligation upon us to go in if they comply with the requirements set out; if they do not accede we are released from all responsibility.”

Hoover could not have been surprised by Gorky’s appeal. In the first week of June, the ARA received reports on the severity of the Russian crisis. Hoover communicated to his top subordinates in the ARA that operations in other countries were to be halted so that they could begin building up supplies for a possible mission to Russia. He wanted to be ready, should the Soviet government collapse or be overthrown, to show Russia the goodwill of the American people. His motives were twofold: the desire to fight both hunger and Bolshevism.

On July 23, Hoover wired a lengthy telegram to Gorky, explaining that he had been moved by the suffering of the Russian people and laying out what had to happen before any aid might be considered, as well as a necessary general understanding of principles. First, he noted, all American prisoners in Russia had to be released immediately. Next, the following items had to be agreed to: (1) that the Soviet government must officially state that it was requesting the assistance of the American Relief Administration; (2) that Mr. Hoover was acting not as secretary of commerce but in an unofficial capacity, as the head of a relief agency, so that help from the ARA in no way signaled official U.S. government recognition of the Soviet state; (3) that the ARA would operate in Russia as it did in all other countries: namely, its workers would have complete liberty to come and go and travel about, free of interference; that they would have permission to set up local aid committees as they best saw fit; and that the Soviet government would cover all costs associated with the transportation, storage, and handling of ARA supplies. In return, the ARA promised to give food, medical supplies, and clothing to one million children “without regard to race, creed, or social status.” Finally, Hoover affirmed that the representatives of the ARA would refrain from any political activity.

If the Soviet leadership had any doubts, reports from the provinces that month may well have convinced them to put them aside. In the middle of July, the vice-chairman of the Samara Province Executive Committee sent a secret telegram to Lenin, outlining in clear terms just how dire the situation had become: “ There are no more grain reserves in the district capitals. State dining halls are all closing. Children are starving in the orphanages [. . .] The cholera epidemic has taken on terrifying proportions [. . .] Samara is now the breeding ground of a contagion, the consequences of which threaten the entire republic [. . .] The population is fleeing from Samara Province, the train stations and wharfs are over-flowing with refugees. Famine, epidemic.”

From the start, the ARA mission to Russia was subject to political pressure back at home. When word of Hoover’s reply to Gorky became public, the ACLU objected in the pages of The New York Times to linking the offer of aid to any political conditions. The Nation criticized Hoover along similar lines, noting that surely there were Soviet citizens in U.S. jails, and so who were we to expect the Soviets to release Americans if we did not do the same to Russians. Some on the right saw in the famine the opportunity to strike a blow against Bolshevism. John Spargo, an erstwhile socialist turned rabid Republican anti-Red crusader, wrote Secretary of State Hughes, “The present crisis presents an opportunity which, if rightly used, may lead to the liquidation of the Bolshevist regime and the beginning of a restoration.” He recommended they work together with the newly created All-Russian Committee for Aid to the Starving, an organization that included many anti-Bolshevik intellectuals and prerevolutionary political and cultural leaders, which Lenin had reluctantly agreed to sanction, although chiefly for cynical public-relations efforts in the West. Lenin let the other Soviet leaders know that a close watch would be kept on the committee, and that as soon as it had served its function, it would be closed and its members dealt with. As for Spargo, he, like some other opponents of the Soviet regime, thought the committee could become the basis of a representative government in Russia once the Bolsheviks had fallen.

Paul Ryabushinsky, an adviser to the embassy of the Russian Provisional Government in Washington, D.C., met with Hoover’s assistant Christian Herter to tell him in secret that Russian émigrés were prepared to provide money and supplies to the ARA that it could funnel to the All-Russian Committee for Aid to the Starving. Their goal was to use the ARA to help undermine the Soviet government and replace it with the committee once the Soviets had been overthrown. Herter declined to endorse Ryabushinsky’s plan.

All of this was taking place in the shadow of the Red Scare that had gripped the United States in 1919–20. After the war, the country had experienced a wave of strikes and worker agitation, and there was the fear that Bolshevik influence might spread outward from Russia to destabilize the West. The U.S. Senate organized a subcommittee to investigate the threat of the “Red Menace” to civilization. In the spring of 1919, anarchists began a bombing campaign against key politicians, state officials, and businessmen, including John D. Rockefeller. One bomb was mailed to the home of U.S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer. An enraged Palmer responded with the so-called Palmer Raids. By December, 249 radicals had been caught and placed on a ship leaving for Finland, whence they would be free to make their way to Bolshevik Russia. Among them was the “Red Queen,” Emma Goldman. One of the young agents hired by Palmer to hunt down the radicals was a nineteen-year-old civil servant by the name of J. Edgar Hoover. In the end, thousands of suspected radical subversives were deported. Palmer announced that the Reds planned to overthrow the U.S. government on May 1, 1920. When the day came and went with no revolution, Palmer’s credibility took a hit. Still, the violence, and the hysteria, continued. On September 16, a bomb exploded on Wall Street, killing thirty-eight people.

Staunch anti-Bolshevik though he was, Hoover appears to have looked upon the hysteria of the Red Scare as misguided and overblown. Even though the Red Scare had calmed down by the summer of 1921, many Americans still saw no difference between the Bolsheviks and the Russians, so that helping one was helping the other. But Hoover always insisted on keeping the two separate: “We must make some distinction between the Russian people and the group who have seized the Government.” Moreover, Hoover’s reputation as an enemy of Bolshevism was just the thing for an American trying to win support for a relief operation to Russia: it immunized him against the charge that his ultimate goal was to help save the young Soviet regime.

On July 26, a mere three days after sending his list of conditions, Hoover received a reply from Gorky stating that the Soviet government looked favorably on his offer. Two days later, Lev Kamenev, an old Bolshevik, a longtime comrade of Lenin, chairman of the Moscow Soviet, and head of the Committee for Aid to the Starving, sent Hoover an official letter of acceptance of relief on behalf of the government. He promised that the American prisoners would be freed and proposed that the two sides immediately sit down to agree on the conditions necessary to begin the enormous task of feeding the hungry.

NEGOTIATIONS BEGAN IN THE BALTIC CITY of Riga, capital of the newly independent state of Latvia, on August 7. Walter Lyman Brown, the London-based director of the ARA for Europe, represented the American delegation, together with his assistants Cyril J. Quinn, head of the ARA in Poland, and Philip Carroll, ARA chief in Germany. The Soviet team was led by Maxim Litvinov, deputy chairman of the People’s Commissariat for Foreign Affairs. The chain-smoking Litvinov spoke fluent English and was an intelligent and highly skilled negotiator—persuasive, wily, and tough. Once, Litvinov’s revolver fell from his coat pocket and crashed onto the negotiating table. Quinn worried that if all Bolsheviks were like Litvinov, they were in big trouble.

Two days before the negotiators met, Lenin instructed Kamenev to hurry up with the release of the American prisoners, and the Soviet government did manage to accomplish this in time. But no sooner had the two sides sat down than Litvinov pushed back on two of the ARA’s key demands: a voice in determining which regions to serve, and the right to set up local relief committees without Soviet interference. Disagreements also arose over questions concerning the ARA’s freedom of movement about the country and who would have ultimate control over the distribution of food and other relief: the ARA or the Soviet authorities. As for the Americans, Brown wanted to backtrack on Hoover’s reference, in his telegram to Gorky, to helping one million children, proposing instead that they drop any mention of a specific number and promise only to feed as many as possible. He also added the stipulation that, as in other countries served by the ARA, all warehouses, offices, vehicles, trains, and kitchens be prominently marked as belonging to the “American Relief Administration” and that, wherever possible, these identifications include the image of their boss, Herbert Hoover. If the ARA was going to go to the considerable trouble of aiding the people of Russia, it was going to make certain everyone there knew just who it was who was helping them.

A wall of mistrust divided the two sides. The Americans worried about compromising the independence of the operation and simply handing over relief supplies to the Soviets to disperse as they saw fit, without American control. They would offer aid on their own terms, feeding as best they could everyone in need, not just loyal supporters of the regime, and were careful not to let themselves be used by the Soviet government for their own designs. The Soviets worried about a good many things, chiefly that the true goal of the operation was the overthrow of their government.

Lenin, in declining health and suffering from insomnia and horrible headaches, nervously followed the talks from Moscow. He sent Litvinov a radiogram on August 11: “Be careful. Try to gauge their intentions. Do not let them get insolent with you.” He insisted on being kept informed of every detail during the talks. Lenin seethed with anger when he heard the Americans’ demands, especially about noninterference with the ARA men once they were inside Russia. Hoover and Brown were “impudent liars,” he wrote the same day to Vyacheslav Molotov, secretary of the Communist Party throughout the 1920s and then foreign minister under Stalin. Lenin insisted, “Hoover must be punished, he must be publicly slapped in the face so the whole world can see.” He demanded Litvinov set “very strict conditions: for the slightest interference in internal matters—expulsion and arrest.” The Red Newspaper captured the mood with an article titled “The Greek Hoover and His Gifts”: the ARA was a modern-day Trojan horse presented to foment counterrevolution; if the ARA was permitted into Soviet Russia, the newspaper demanded, it would have to be not only watched but placed under tight government control.

The most fanciful comment on the ARA came from Leon Trotsky, the brilliant Marxist theorist and ultimate master of spin, in a speech before the Moscow Soviet. While acknowledging that Russia was facing a serious famine, Trotsky assured his audience that the government could handle it without outside help. No, he proclaimed, it wasn’t Soviet Russia that needed the West, but the other way around: the capitalist world was facing a commercial and industrial crisis of unprecedented scale (the depression of 1920–21 had indeed been bad, but the worst was over by then), and its only chance at survival was in finding a way to draw Russia back into the world economy. “What is at stake is the very basis of bourgeois rule,” Trotsky told his audience. In other words, America would not save Russia, but Russia might well save America. The offer of relief by the ARA had nothing to do with a real concern for human welfare; rather, it amounted to nothing more than an aggressive move by the missionaries of American capital, who were certain to be followed by businessmen, traders, and bankers.

There was one gaping hole, however, in Trotsky’s depiction of the current situation: if the government truly could handle the famine without Western help, why, then, was it willing to make “big concessions,” as he characterized them, to the ARA, especially if the Americans posed such a serious counterrevolutionary threat? To this, the great Marxist dialectician had no answer. In fact, Russia could not get by without outside help, as Kamenev had made quite plain in a speech the month before, admitting, with all seriousness: “We know that our resources aren’t enough to even begin to halt this disaster. We must have help from abroad, especially help from foreign workers and also all kinds of public organizations in Europe and America that are able to recognize the necessity of help regardless of our political differences.”

An article titled “Stemming the Red Tide” that had appeared that spring in the journal The World’s Work seemed to validate Soviet suspicions of the ARA. The author, T.T.C. Gregory, a brash lawyer from San Francisco with an inflated sense of his role in world events, had served in the ARA in Central Europe after the war. Gregory described how he and Hoover had hatched a plan to overthrow the communist government of Béla Kun in Hungary by withholding food relief to Budapest in the summer of 1919. “Way down in my heart,” Gregory wrote, “I knew that we were not only feeding people but also were fighting Bolshevism.” His actions had shown the incredible power of food “as modern weapons.” After his cunning maneuver to stop the spread of the “Red Menace,” as Gregory saw it, no one could deny that “Bread is mightier than the sword!”

Though it’s true that Hoover could not stomach the Kun regime, Gregory’s boast was pure fancy. (The imaginative Gregory also claimed he prevented the Habsburg restoration after the fall of Kun: “My blood was up . . . A member of the Habsburg family? Not while I could have a word to say, at any rate!”) The Hungarian Soviet Republic, which lasted a mere 133 days, collapsed of its own making, largely because of the regime’s military aggression toward its neighbors, and not the derring-do of T.T.C. Gregory, attorney-at-law. Nevertheless, the article, soon reprinted in Soviet Russia, confirmed the Russians’ darkest fears about Hoover and the ARA.

Gregory’s piece gave ammunition to the American left as well. The Nation took up the story and accused Hoover of putting politics ahead of people. Another left-wing magazine commented, “Everything that is known about Mr. Hoover [. . .] conveys ample assurance that he would use his position in Russia for political purposes.” While negotiations were under way in Riga, the American Labor Alliance held a rally in New York City at which the main speaker openly accused Hoover of planning to overthrow the Soviet government by taking control of the country’s food supply.

Attacks also came from the right. Henry Ford’s Dearborn Independent maligned the mission and attacked the ARA as poorly administered and venal. There were nasty suggestions that the ARA was controlled by Jews and Bolsheviks. Another Midwestern newspaper asked why America should “interest itself in perpetuating a dynasty of darkness that is dying because of its incompetence.” Criticized by both left and right, Hoover let his men know that the ARA would avoid politics at all costs. He sent a cable to Brown in Riga on August 6, a day after Herter’s meeting with Ryabushinsky:

I wish to impress on each one of them [employees of the ARA] the supreme importance of their keeping entirely aloof not only from action but even from discussion of political and social questions. Our people are not Bolsheviks but our mission is solely to save lives and any participation even in discussions will only lead to suspicion of our objects. In selection of local committees and Russian staff we wish to be absolutely neutral and neutrality implies appointment from every group in Russia and a complete insistence that children of all parentage have equal treatment.

Along with instructions to his agents, Hoover also maintained an ARA public-relations department, led by George Barr Baker in New York, that put out a steady stream of uplifting press releases, maintained good relations with the Western press, and sought to counter any negative publicity. Hoover was not about to let anyone tarnish his reputation or that of the American Relief Administration if he could help it.

IN RIGA, TALKS had reached an impasse. On August 12, the local newspaper published an interview with Litvinov in which he affirmed that the Soviets would “never agree to any conditions that may have the slightest effect of discrediting our government. We will never let any foreign administration use the terrible conditions in the Volga District to force the Workers’ and Peasants’ Government to accept conditions that are against our honor.” The following day, he sent a cable to his boss, Georgy Chicherin, people’s commissar for foreign affairs: “I have the impression that the ARA has come to us without any ulterior motives, but still we’re going to have plenty of trouble with them.” The two sides had had no success in coming to any sort of agreement over the ARA’s autonomy and who would be in charge of handing out the food. Litvinov kept reminding Brown and the other Americans, in his heavily accented English, “Gentlemen, food iz a veppon.” Of course, Litvinov knew this well from recent history. The Soviet government had given extra rations to social groups that supported the regime and denied food to its enemies, both real and imagined. They had used food as a weapon in the struggle to win the revolution and create the first communist state. And they needed food now to prevent the state from collapsing, but the question was: if food was a weapon, whose finger was going to be on the trigger?

Brown wired Hoover on August 15 that the talks were deadlocked and they would have to make some concessions. At first Hoover refused, but he soon realized it would be best to do whatever he could to make a deal. He agreed that the ARA would not hire any non-Americans without the approval of the Soviet authorities, and that the ARA would fire from its staff anyone the Soviet government complained about, if there was the least bit of evidence of any political or counterrevolutionary activity on that person’s part. The Americans also agreed to permit the Soviets to expel any person caught engaging in political or commercial activity and granted them the right to search premises in which they believed a crime had taken place, and reinstated the reference to feeding one million children first made in Hoover’s telegram to Gorky. Nonetheless, the Americans refused to concede the point about the Soviets’ obligation to cover all the costs of transporting, storing, and administering the aid, as well as the ARA’s right to work in those terrorities it deemed needing assistance. Litvinov, after hearing of Hoover’s concessions, had no trouble agreeing to this: “Money, gentlemen, ve vill give you a carload; if necessary, ve can put the printing presses on an extra shift.”

After almost two weeks of negotiations, the two sides agreed to terms on August 20. The following day, at a ceremony presided over by the president of Latvia and attended by various officials and members of the world press, the Riga Agreement was signed. Litvinov told the gathering that this was an occasion of great political significance, expressing the hope that it signaled the rapprochement between the United States and Soviet Russia. Brown chose to ignore Litvinov’s comments in his own remarks. As Hoover had insisted, the ARA mission to Russia was to be above all politics.

LENIN HAD FOLLOWED the talks closely. Having to accept help from capitalist America was a bitter pill. On August 23, he sent a secret letter to Molotov: “In light of the agreement with the American Hoover we are facing the arrival of Americans. We must take care of surveillance and intelligence.” He instructed the Politburo to set up a special commission that could come up with a plan. “The main thing is to identify and mobilize the maximum number of communists who speak English so that they can be inserted into the Hoover commission, as well as coming up with other forms of surveillance and intelligence.” Two weeks later, Lenin, now even more alarmed at the thought of so many Americans entering the country, wrote Chicherin: “As for the ‘Hooverites,’ we must shadow them with all our might [. . .] and we ought to ‘catch’ and entrap the worst of them (a certain Lowrie?*) in such a way as to produce a scandal around them. This calls for war, a brutal, unrelenting war.”

As a way of deflecting attention away from the ARA, Lenin created the International Workers’ Committee for Aid to the Starving in Russia (Mezhrabpom, in Russian) that same month. The appeal to the world proletariat to come to the aid of the first communist state did little to help the starving—its total relief effort amounting to a mere 1 percent of that marshaled by the ARA—but Mezhrabpom did function as a useful propaganda tool, especially in the United States, where it operated as the Friends of Soviet Russia. In the middle of August, a meeting was convened in Geneva by a number of Red Cross societies to discuss the possibility of organizing aid to Russia. They established the International Committee for Russian Relief and elected Fridtjof Nansen, to whom Gorky had first sent his appeal for help, as its high commissioner. The Nansen mission, as it was known, brought together relief organizations from over twenty countries. Among the groups that came to Russia’s aid were the British Society of Friends, the Save the Children Fund, the Red Cross of Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, Czechoslovakia, and Belgium, and His Holiness the Pope.

Nansen left Geneva for Moscow, where he was warmly embraced by top Soviet officials, in large part because he was much more cooperative than Hoover and the ARA. Nansen had no serious experience in relief operations, nor did he have a large organization at his disposal, and so he offered to turn over to the Soviet government whatever supplies he managed to gather. The Soviets could not have been happier. The relief provided by the Nansen mission was significant, although modest when compared with what the ARA provided: approximately 90 percent of all aid delivered to Russia came from the Americans. Nevertheless, Nansen was fêted by the Kremlin as a true friend of the Soviet state on both of his two brief visits to Russia. Some in the West viewed the Norwegian as a naïve tool of the Soviet regime, and the exaggerated praise showered on Nansen—and his associate Vidkun Quisling, the notorious president of Norway during the years of Nazi occupation—drove the ARA men mad. Nansen’s being awarded the Noble Peace Prize was but more salt in the wounds.

After the troubles dealing with the Americans in Riga, Lenin was in no mood to bargain with Nansen. He wrote to Stalin, then both commissar for nationalities and commissar for the workers’ and peasants’ inspectorate (Rabkrin), on August 26: “Nansen will be given a clear ‘ultimatum.’ We’ll put an end to this game (with fire).” To show Nansen in no uncertain terms that he was not playing around and that the Soviet leadership was in complete command of the situation, Lenin also instructed Stalin to shut down the All-Russian Committee for Aid to the Starving before the Norwegian left Russia. On August 27, Cheka agents moved on the committee, arresting its non-Bolshevik members and charging the group with secretly negotiating with “foreign powers” behind the government’s back and even trying to establish contacts with the remnants of Antonov’s peasant army. Two of the committee’s leaders were sentenced to death ( later commuted), and the rest were exiled from Moscow—to towns without any rail connections—and placed under surveillance. Lenin ordered that the committee be denounced in the harshest terms in the press no less than once a week for the next two months. Foreigners were arriving in Moscow, and Lenin was going to make certain no critics of the government would be there to meet them.

Indeed, around 6:00 p.m. that same evening of the 27th, the first group of ARA men arrived by train in the Soviet capital. The mission had begun. As the Americans were approaching Moscow, Walter Lyman Brown wrote to Hoover: “It is going to be by far the biggest and most difficult job we have yet tackled and the potentialities of it are enormous, but I think we can pull it through.” Neither Brown nor anyone else in the ARA had any idea just how big or difficult the Russian job was going to be.

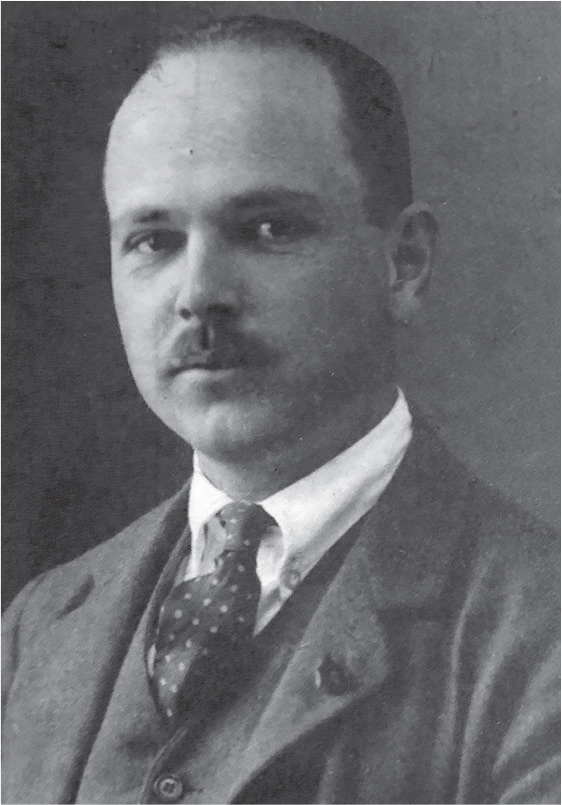

LATE ONE AFTERNOON IN JULY during the sweltering summer of 1921, two young American men sat whiling away the day at the Café du Commerce in the small French town of Château-Thierry. Charles Veil—fighter pilot for the Lafayette Flying Corps in the war, turned playboy-adventurer in peacetime—was reading the Paris edition of the Chicago Tribune when he looked up at his friend and casually remarked: “ There’s a famine in Russia and an appeal has been made to America for aid. It seems the American Relief Administration may go in.” J. Rives Childs took the paper and read Gorky’s appeal. In an instant, Childs was seized with the idea of signing up and heading off to Russia. “If the deal goes through, there will be big news,” a grinning Childs told Veil. “Right now Russia is a closed book.”

Childs was a son of the South, born in Lynchburg in 1893 to an old Virginia family. His father had served as a messenger for General Lee in the Civil War and then went on to a career in business that ended badly, in a bank failure. His mother was the stronger, more influential of his parents. A college graduate, she was the first white woman in Lynchburg to teach in a school for black children, much to the displeasure of the local white superintendent. She made sure her son got an education, sending him to the Virginia Military Institute, then Randolph-Macon College, and finally on to Harvard College for a master’s degree in English. Young Childs had dreams of becoming a writer. One day, the radical journalist John Reed came and spoke to the class about his dangerous experiences on the Eastern Front. Childs’s head was filled with the allure of foreign adventures.

Soon after, in the summer of 1915, he and a friend volunteered for the American Ambulance Corps and sailed for Europe. For several months, he ferried wounded French soldiers under the distant rumble of heavy guns from Compiègne to the College of Juilly, not far outside Paris. After the United States joined the war, Childs was commissioned as a second lieutenant and sent to intelligence school, then served with the American Expeditionary Force in the Bureau of Enemy Ciphers in Chaumont, France. In December 1918, he was assigned to the American delegation to the Paris Peace Conference as a radio intelligence officer. There he watched his hero, President Wilson, parade down the Champs-Élysées amid wildly cheering crowds. Wilson’s idealism, his progressive political agenda, and his vision of a new world order based on democracy and national self-determination inspired Childs and would become signposts in his life. As Wilson rode past, Childs was so overcome with emotion he had to walk away from the crowd and try to collect himself in private.

Childs fell in love with Europe, and when his job in Paris ended, he began looking about for anything that would keep him from having to return to the States. He heard about the newly established American Relief Administration and was hired on to help feed hungry children in Yugoslavia. It was just the posting he had been looking for. “The Balkans were remote and romantic,” he later recalled. The job ran until the autumn of 1919, when he reluctantly returned home. His disappointment was somewhat lessened after he won a job as the White House correspondent for the Associated Press. He met his idol on a few occasions, but then was nearly crushed with despair at the 1920 election of the Republican Warren G. Harding, whom he characterized as “a ponderous piece of flesh” and “a great tragedy for the American people.” Childs’s choice for president had been Eugene V. Debs of the Socialist Party of America. He was now more eager than ever to get back to Europe. In the spring of 1921, Childs managed to land a writing assignment that would take him to France for several months. He jumped at the opportunity.

ON AUGUST 1, Childs made his way to the American Express Office at 11 rue Scribe in Paris. In the Visitors’ Writing Room, he wrote a letter to Walter Lyman Brown in London, reminding Brown how the two had met back in 1919, before Childs shipped off for Yugoslavia, and offering his services for the job the ARA was preparing to undertake in Russia. He told Brown that serving with the ARA had been a great honor and no other work in his life had given him such satisfaction. He was prepared to come to London at a moment’s notice to discuss with him in person the chance of going to Russia. He closed his letter by remarking that he already possessed a fair conversational knowledge of the Russian language. This was a lie, but, then, Childs was willing to do just about anything to return to the ARA.

Two days later, Brown cabled Childs, inviting him to come to London. Childs was overjoyed. He immediately wrote his mother: “ There seems to be the prospect of a spirited adventure in Russia and you may be sure that if it is possible I shall be heading that way before returning home.” He made no mention of the famine, or of communism, or of potential business opportunities, only that a job with the ARA would provide him with “some interesting material for stories.” Childs’s motivation for heading off to Russia—the prospect of adventure, the lure of the exotic and the unknown, a motivation shared by many, if not most, of the young Americans who signed up for the ARA mission—never once crossed the minds of Soviet officials. After three revolutions and three wars in two decades, the Russians had had plenty of “adventures,” more than most nations experience in the course of a century or two. They could not even conceive of a country where life was so steady that its young men sought out the world’s troubled spots merely in the hopes of quickening their pulse. A cloud of misunderstanding obscured the Americans from the Russians, and it never lifted, not even after years of close work together in the fight against the famine. Childs was in Vienna on the 20th when he received a wire informing him an agreement had been made with the Soviet government and instructing him to head to Riga by the shortest possible route. He nearly burst with excitement. “It will be a tremendously big job and one which any man should be proud to have a hand in. To be among the first expedition I consider a boon sent directly from Heaven,” he wrote his mother. He had a sense based on his previous work for Hoover that they’d be engaged in more than just famine relief. Hoover’s true aim, he seemed certain, was “the ultimate economic reconstruction of the country.” Childs hadn’t felt so alive since his days in Yugoslavia. “The old fever to be among stirring scenes and a part of great events is once more about to be satisfied.”

J. Rives Childs

Armed with a Russian dictionary, Childs set off for Riga by way of Berlin. He asked his mother to send him his wool socks, three suits of heavy underwear, and a carton of Camel cigarettes. On the 27th, he reached Riga. There he met Emmett Kilpatrick, a friend from his Paris days. Kilpatrick had been taken prisoner by the Red Army while serving with the Red Cross in southern Russia and spent nearly a year in Moscow’s Lubyanka Prison, much of it in solitary confinement. Childs seemed shocked that his old pal was no longer the fun-loving prankster of former days. Over lunch, Kilpatrick told him of the horrors he had gone through in prison—the filth, the lice, the cold, hunger, and brutality. He had stayed sane by repeating the famous lines of Richard Lovelace’s “To Althea, from Prison”—“Stone walls do not a prison make, nor iron bars a cage.” Childs noticed how his “eyes roved restlessly about him like those of a hunted animal.” Late on the night of the 29th, Childs left for the station and boarded his train for Moscow. At last, he was on his way into what he called “that strange, mysterious world” of Soviet Russia.

Among the small party of Americans with Childs was a middle-aged professor of Russian history from Stanford. Frank Golder had been born in Odessa and immigrated to America as a boy with his family, most likely soon after the bloody pogroms of the early 1880s. As Jews, the Golders hoped for a better life across the ocean, but getting by in New Jersey proved a struggle. Frank’s father, a Talmudic scholar, made little money, and Frank was forced to sell household wares on the street to support the family. One day, he met a Baptist minister who was so impressed by the boy’s work ethic that he persuaded the Golder family to let him give them money to allow Frank to go to school.

As a teenager, Golder studied philosophy at Bucknell University and then went on to Harvard, from which he graduated in 1903, before enrolling in graduate studies in Russian history. After earning his doctorate in history in 1909, he took a position at Washington State College, in the town of Pullman, amid the rolling hills of the Palouse. Golder dreamed of working in Russia’s archives, and he managed to travel to St. Petersburg in the summer of 1914, just as war was breaking out across Europe. He was back again in March 1917, and witnessed the collapse of the Romanov dynasty with his own eyes. Like many, he greeted the February Revolution as a necessary step toward a freer, more just Russia, only to be disillusioned at the chaos and violence that soon followed. He could not believe how quickly a country could go to pieces.

In 1920, Golder was hired by the new Hoover War Collection ( later the Hoover War Library and now the Hoover Institution Library and Archives) at Leland Stanford Junior University to help build a collection of documents on the history of the Great War. Stanford would become his home for the rest of Golder’s life, both as a professor and as director of the Hoover Library. Golder traveled all over Europe, buying up manuscripts, libraries, and ephemera for Hoover. Everywhere he went, he was met with open arms. Modest, soft-spoken, a good listener who never tried to impose his views on others, Golder developed an enormous network of contacts among the continent’s intellectual elite, including in Russia. Few if any Americans in 1921 could boast of a more thorough knowledge of Russia—its history, culture, and politics—than Frank Golder, and it was for this reason that his employer, Herbert Hoover, sent him back to Russia that summer, to continue his collecting and to assess the famine as a special investigator for the ARA. “Doc” Golder, as he was affectionately called by the ARA men—all a good deal younger, and almost all a good deal less educated than he—would cover more ground over the next two years than any other American in his search to discover the full extent of the famine.

Frank Golder

The electricity on the train had gone out, so the men rode through the night by candlelight. When they crossed the frontier, Childs was shocked to see that everyone was dressed in rags. The faces of the Russians seemed to betray a dull-wittedness the likes of which he had never seen before in Europe. Trains loaded with refugees from Moscow passed them along the way. Their locomotive was so underpowered that it failed to summit a few small hills along the route. Twice the engineer had to back up the train a good ways and give it all she had to get over the gentle inclines. After a forty-hour trip, the train finally pulled into Moscow on the afternoon of August 31; here they were met by Philip Carroll.

The first group of ARA men had “gone in,” as one called it then, several days earlier. Russia had been almost completely cut off from the rest of the world for over three years. A palpable sense of excitement, mixed with foreboding, had filled their car as they crossed the border. They were entering a strange new land and had little idea what lay ahead. A man from Universal News came along to film their progress behind the Red Curtain. There were seven of them, led by Carroll, acting chief of the Russian mission, a longtime ARA man from Hood River, Oregon. He’d been sent in with no specific instructions from either the New York office or Hoover. As would be the case in much of the mission to come, the men on the ground had to make it up as they went along. The Soviet officials meeting them at the station were shocked: they’d been told to expect only three men and had no idea where they were going to put up an extra four. It seemed a bad omen. With a bit of work, Carroll managed to secure a large gray stone mansion at 30 Spiridonovka, just blocks from Patriarch’s Ponds, later made famous by Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita. Once the luxurious, state-of-the-art residence of a wealthy Armenian sugar baron, its thirty rooms had been reduced, in Carroll’s words, to “an absolute state of filthiness.” The central heating was kaput, the electricity dead, and the plumbing, one ARA man put it, “only a memory.” No one bothered to remove their heavy coats or gloves after moving in. Fifty portable oil-burner heaters were immediately ordered from London.

At the station, Carroll picked up Childs, Golder, and four others on the team in one of the ARA’s freshly painted Cadillacs. Childs noticed how the Muscovites stared as they drove through the city. When they pulled up at their new home, Childs thought Spiridonovka had the look of a dark and massive prison. Carroll seems to have read Childs’s mind, commenting as they went in, “It should be able to withstand a long siege.”

The next day, Childs went out to explore. “I wish that I might give a faithful picture of my impressions of this strange unreal city of Moscow,” he wrote his mother, “but for the difficult portrayal the extraordinary emotions which it awakens there is demanded the morbidly-minded genius of a Poe or E. T. Hoffmann. It is like some great city upon which a pestilence has settled and in which the population moves in hourly expectation of death.” Everywhere were signs of artillery and machine-gun fire, craters where once had been buildings, formerly exquisite shops all now boarded up and cobwebbed. Several years’ worth of trash lay in the streets, and the ground floors of the abandoned structures served as public toilets. Yet more striking than the physical image of the city was the sight of its inhabitants. Childs could not get over “the apparent absence of a heart and soul with which one is struck so forcibly and pathetically. I think that perhaps the briefest and most just characterization of Moscow would be to say that it is a city without love.” Nowhere did he encounter a laugh, or even a smile, as he walked along. There was “rust and corrosion upon the heart and a pall of fear upon the soul.”

ARA headquarters in Moscow, on Spiridonovka Street, with its fleet of Cadillacs and their drivers. The automobile assigned to Colonel William Haskell, who arrived in Moscow in late September to replace Philip Carroll as head of the Russian operation, distinguished by the license plate “A.R.A. 1,” is on the far right.

The Americans got to work straightaway. On September 1, the SS Phoenix arrived in Petrograd from Hamburg, bearing seven hundred tons of ARA rations. Five days later, the first ARA food kitchen opened, in School No. 27, on Moika Street. The first kitchen in Moscow opened on the 10th, in the former Hermitage Restaurant, a beloved establishment for the city’s wealthy in the days before the revolution. Given the great distance food had to be shipped, the meals consisted of products that could be easily packaged and stored and offered lots of calories, usually corn grits, rice, white bread, lard, sugar, condensed milk, and cocoa.

Golder had spent the first two days running around to meetings with Soviet officials in order to make arrangements for a trip to the heart of the famine on the Volga River. No one on the Soviet side seemed to be in charge, and he was having a devil of a time getting any concrete answers about exactly when preparations would be ready for him to depart. Finally, late on September 1, he was told to go to the station for a train leaving at midnight. With Golder were his fellow ARA men John Gregg and William Shafroth, as well as a Soviet liaison officer, two Russian porters, and a driver for the Ford camionette they’d be taking along with them on the train.

They awoke to heavy rain the next morning. Golder noted that the landscape reminded him of northern Idaho, although the desperate, hungry faces at the stations they passed through left him no doubt he was in Russia. Late on the morning of the 3rd, they pulled into the city of Kazan, the old Tatar capital on the Volga, some 450 hundred miles east of Moscow. The men were now inside the famine zone. Hungry refugees from the outlying villages thronged the station, all “huddled together in compact masses like a seal colony, mothers and young close together,” in Golder’s words. The children were surviving on a bit of soup and one small piece of bread from the public kitchens. The city itself was a ruin. In the streets they encountered “pitiful-looking figures dressed in rags and begging for a piece of bread in the name of Christ.”

A wing of the Alexander Palace at Tsarskoe Selo, home of Tsar Nicholas II and his family, was converted into an ARA kitchen that fed more than two thousand children a day. The kitchen was run by one of the tsar’s former cooks and several servants of the last Romanovs.

They went to the offices of the Tatar Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic to introduce themselves to the local authorities. The Tatars received them with an air of suspicion, as if they’d been warned to be on guard. When they learned, however, that Golder was a teacher, as the Tatar officials themselves had been before the revolution, and spoke perfect Russian, their caution melted away. Together the men went off to tour the local hospital. The conditions were abysmal: filthy and lacking the most basic of medicines, the rooms overcrowded with persons afflicted with tuberculosis, scurvy, typhus, and dysentery. Upon returning to their railcar, they found it was besieged by begging children and their wailing parents—a pitiful sight that made it impossible for the men to eat or rest. On the 5th, Gregg sent a wire to headquarters in Moscow: “The need for relief in this country is beyond anything I have ever seen. Speed is of utmost repeat utmost importance as without exaggeration children dying [of] actual starvation every day.” The situation was much worse than anyone had imagined.

That month, Golder traveled throughout the famine region. Everywhere he went, he encountered the same scenes of hunger and despair. At one small station on the way to Simbirsk, two militiamen told him they had not been paid in months and received nothing from the government but one bowl of watery soup a day. They had taken to making a bread substitute out of grass and acorns, which Golder mistook for horse manure.