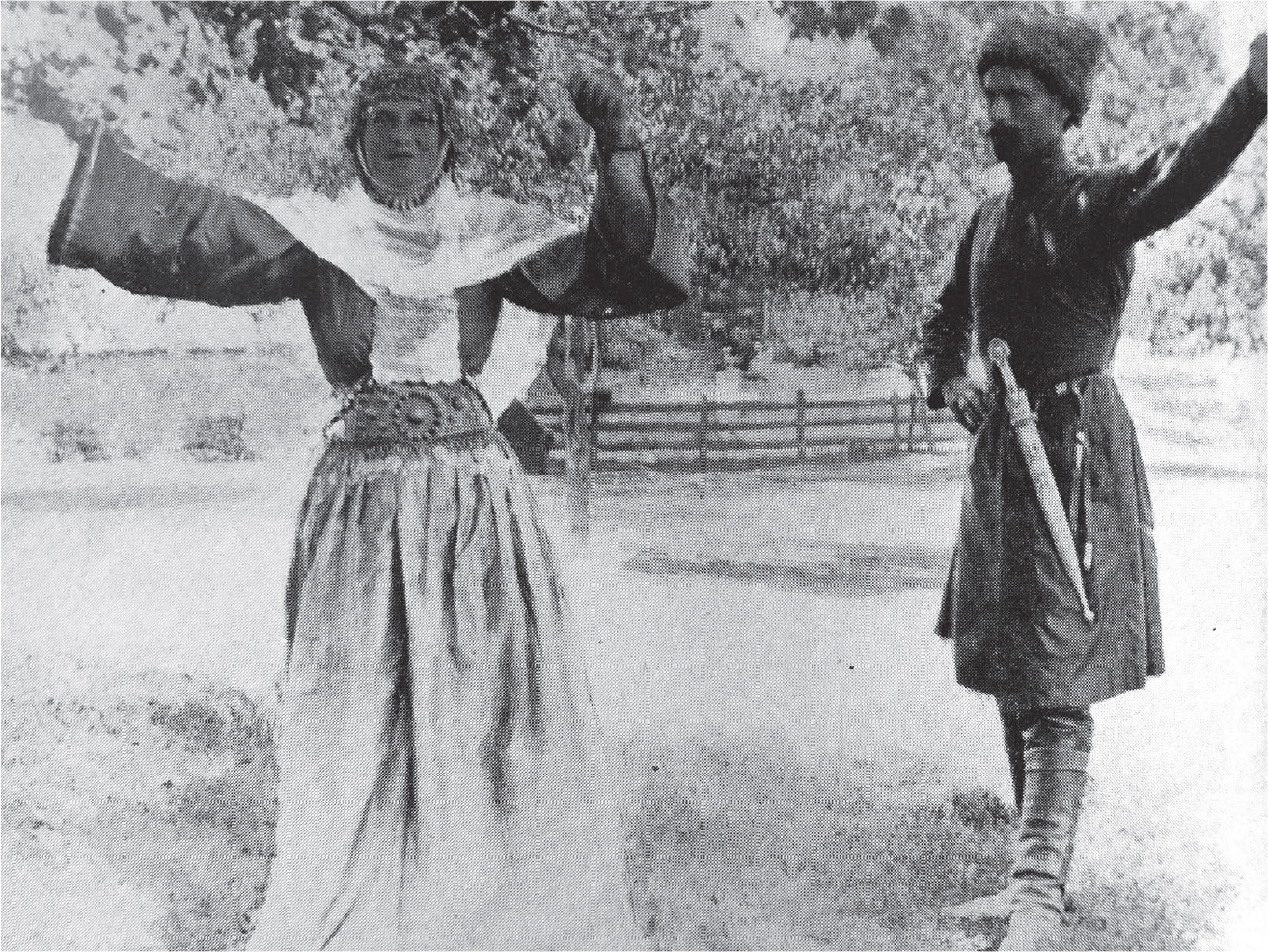

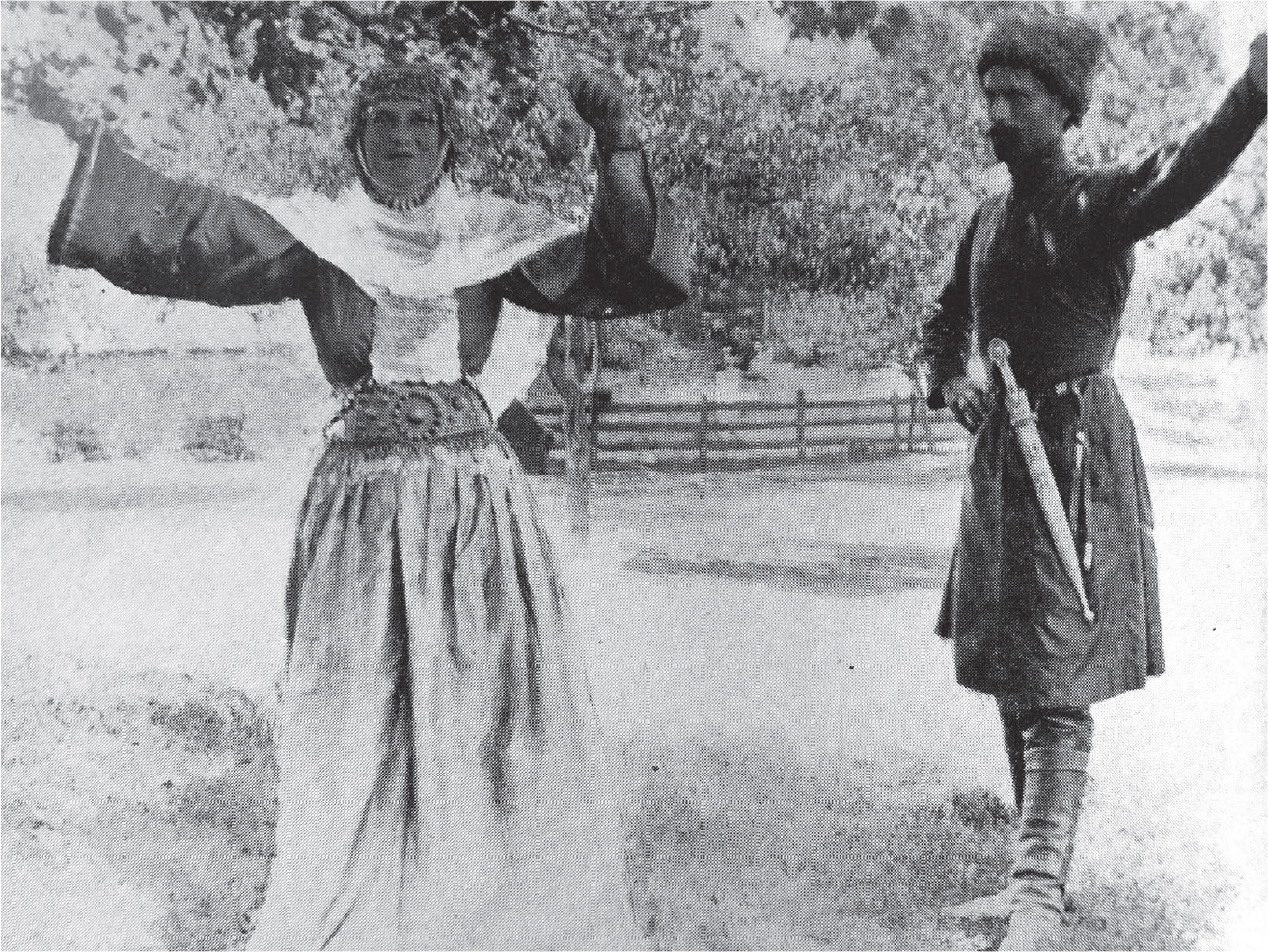

A couple dancing the lezginka for Golder and his traveling companions

ON JANUARY 8, 1923, Frank Golder wrote to his friends Tom and Sigrid Eliot back on the Oregon coast to thank them for their Christmas letter, which had warmed him with memories of pleasant times spent together. The Eliots shared Golder’s desire for better relations with Russia, although they saw the reasons for the tensions between the two countries very differently. They suggested in their letter to Golder that Hoover and Hughes were the problem, which he disagreed with. He told them that the U.S. government had been doing everything possible in the past year to improve relations, but its efforts had failed because of the pettiness of the Soviet leadership. “The Reds,” he noted, “are eager to get our goodwill and more eager still to get our bourgeois capital,” but were constantly throwing up roadblocks and doing things that impeded their own interests. Golder admitted there were some “noble men” among the leaders, “but large numbers of them are rascals who are crushing the spirit of the movement.” It grieved him to read the attacks on the ARA in publications like The Nation, or to hear of the words of men like Paxton Hibben about how the Soviet government was the only honest one in the world. He’d never understand how good people back home could run down Hoover and the ARA and praise the Soviets.

Discouraged though he was, Golder remained an advocate for recognition. He laid out his thinking on U.S.-Soviet relations that month in a long confidential letter to Hoover’s assistant Christian Herter, which he asked him not to share with the State Department. Bad though the tensions were at the moment, he was still convinced that, by establishing political relations, the United States might exercise a moderating influence on Russian domestic life, helping to further its move away from the radicalism of the early years following the revolution. The process would be gradual, however, and there could be no hope of any “immediate material profit.” In Soviet Russia “ there are no fundamental laws, no basic principles of justice as in England, no constitutional guarantees as in the United States for the individual or his property.” Life here was characterized by the arbitrary use of power. People could be arrested at any moment, for any reason, with no warrant, and their property taken without explanation. In such a chaotic and uncertain environment, there could be no foreign investment in the economy. “The financial conditions are so disturbed,” he concluded, “that it is impossible to do big business.” No one in Russia could make any plans for tomorrow, and so they all lived only for today.

If America had little to gain materially from Russia, Golder believed she had much to gain spiritually. He had spent a recent weekend in Petrograd, taking in some ballet and opera, and came away deeply moved by the artistry and beauty of the productions. It pained him to see the terrible conditions in which Russia’s artistic community was forced to live and try to carry on its proud tradition. Nonetheless, Golder took comfort in the fact that many of the young American men attached to the ARA had been attending the theater, and its influence was clear to him. “We are giving Russia bread, but it is giving us something more precious in turn.” He was convinced that their encounter with Russian culture had changed these young and, in his opinion, unrefined Americans, and they would take this enlightened sensibility back home and release it into American life.

IN MID-JANUARY, the vice-president of the Dagestan Republic arrived at the Moscow offices of the ARA to ask for help in feeding the starving people of his mountainous region. Dagestan, a beautiful land of dizzyingly diverse ethnicities and languages located on the western shore of the Caspian Sea north of Azerbaijan, had declared independence in 1917 as the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus before becoming engulfed in the bloody violence of the civil war. Initially welcoming the Red Army as their liberators from the Whites, the Mountaineers, as they were known, soon found themselves robbed of their independence and forcibly incorporated into Soviet Russia in early 1921.

On the evening of February 12, Golder left Moscow on the Tiflis Express to investigate the situation in the Caucasus. Along the way, he noticed that there now appeared to be plenty of food available in the stations they passed. Once they had traveled beyond Rostov-on-Don, conditions improved considerably; food here in the south was both cheap and abundant. The train pulled into Petrovsk, the capital of Dagestan, on the morning of the 16th. It was cold and dark outside, and Golder found the town dirty and smelly. He spent two days surveying Petrovsk and gathering information on the needs of the local people before setting out for the rugged mountains of Dagestan. Traveling with him were five local men: Abdulah, his liaison officer, an intelligent, well-informed, and physically imposing young man who’d fought in the civil war, with whom Golder quickly formed a good bond; Abdulrachman, from the republic’s Department of Education, a cynical, pessimistic, and prematurely old middle-aged man who seemed to carry the weight of the world on his shoulders; Mohammed, their driver; and two bodyguards, Ali Khan and Haji, a peasant from the Dagestani lowlands, decorated Red Army soldier, and wonderful young man with whom Golder established an immediate rapport. Each one of them was armed with a rifle, a revolver, and a dagger.

Golder was struck by the beauty of the mountains, whose peaks rise over fourteen thousand feet, and the auls, or villages, constructed of stone, clinging to the steep ridges as a defense against attack. Much of the time, they had to travel on sturdy ponies along treacherous narrow paths through sheer river gorges, with the ground falling away thousands of feet off to their sides. The children’s homes here were in terrible shape—the children dirty and half starved, living on nothing more than a bit of watery cornmeal soup. The higher up into the mountains the men traveled, the worse the conditions became. In some villages, the children were practically left on their own, because there weren’t enough adults to care for them. Amazingly, some of the American corn had managed to find its way to these remote mountain villages, but it wasn’t much, and the people, Golder found, were barely surviving. Many people told him they had nothing left to do but pray for the mercy of Allah. By the 24th, he had seen enough to know help was desperately needed, and he sent a telegram back to Moscow to ship food and medicine as soon as possible.

A couple dancing the lezginka for Golder and his traveling companions

Despite the gnawing scarcity, the legendary hospitality of the Caucasus greeted Golder everywhere he went—tables heavy with food and wine, attractive pairs of young men and women dancing the lezginka to the accompaniment of the choghur and tambourine.

The feasts could be so large, and long, as to be almost intimidating; polite refusals to the host’s entreaties to more food or drink were futile. Frequently, Golder was taken for an important communist official from Moscow, since most of the villagers had never heard of America. His attempts to explain proved fruitless. In Khunzakh, the old village sage told Golder, “America is the lower world,” a place “so far that no man can go there.” Golder insisted that the man was mistaken, that he in fact lived there. The villager paused and then admitted it might well be possible and offered the theory of a hole in the earth that linked America, the lower world, with Dagestan, the upper world. (Dagestan literally means “land of mountains,” and its inhabitants quite naturally considered themselves to live on top of everyone else.) This idea posed a problem, however: if, some of the villagers asked, America was beneath Dagestan, then how could the people walk there? Wouldn’t they be upside down? This seemed to stump them all until the wise man solved the conundrum by asking them to consider the fly. Did it not walk on the top and bottom of things without falling? The men nodded in agreement.

Word of the exotic American spread. Upon arriving in one aul, Golder and his party found the road lined with the local men as a sign of respect. They’d heard that the American visitor was carrying a large bag of gold with him to buy Dagestan from the Soviets. When Golder told them of their mistake, they asked that he simply buy them instead and take them with him. He apologized and said he’d have to decline their offer; with that, the travelers rode on to the next aul past a line of crestfallen faces.

They returned to Petrovsk on March 6. Golder was delighted to see that an ARA representative had already arrived in response to his telegram and was busy making preparations to receive a large shipment of food and medical supplies. The people of the town, amazed by the speed with which the ARA worked, told Golder that Americans were a very clever people who “can do anything.” By the middle of the month, he was back in Moscow. He wrote Herter of his trip and the “most interesting experience among those wild mountaineers and bandits.”

He also wrote of a conversation he had had the previous day with Radek, who told him what he knew about Lenin’s devastating stroke just days earlier, which had left him unable to speak and partially paralyzed. Lenin had already suffered two serious strokes, in May and then December 1922. After this latest stroke, there appeared little hope of recovery. Golder and Radek wondered aloud what might happen if he died. Radek was certain Stalin would become the leader of the party, which he thought would be a good thing. “He has a very high opinion of the Georgian,” Golder informed Herter. Lenin’s health improved that autumn, but he was just an empty shell of his former self. The country was now in the hands of his old Bolshevik comrades. Lenin died on January 21, 1924, most likely from cerebral arteriosclerosis, although rumors persist to this day that the cause of death was syphilis.

IN EARLY JANUARY 1923, Fleming was sent to Samara. He wrote his parents from there on the 15th to tell them he’d been busy setting up his room with a desk, typewriter, reading lamp, row of books, icon, and two photographs of his dear “Politchka,” whom he had left back in Moscow. He included Paulina’s photograph in his letter, adding with feigned drama that should it get lost, he would quit the ARA and drown himself in the Irish Channel. His letter completed and his bags packed, he set off on a two-week inspection tour later that day.

Fleming, like many other of the young Americans, reveled in the authority entrusted in him as a representative of the ARA. He recalled of this trip:

My travel orders and official duties, I was informed, were a carte blanche to every part of provincial life in Russia, without fear of the government nor favor of the old bourgeoisie. I had an open sesame to all doors and all classes. In the same day I might threaten the chairman of a county ispolkom,* the biggest man in the county, with closing all the kitchens in his county if he did not come to order; I could then talk with a former well-to-do merchant now proscribed and ostracized by the government, and finish the day by attending a peasant wedding where the most violent liquor ever concocted was poured out for the guests.

The richest man in two counties, I was also the only man in two counties who could afford to laugh at the name of the Government Political Department.* I was privileged to talk on equal terms with heads of provincial departments, to open or close kitchens feeding thousands of children, and to give carpet talks to small-town officials for negligence in the discharge of their duties.

Traveling with Fleming was his Russian interpreter, George. A Jewish anarchist in his late twenties, George had been exiled from tsarist Russia and eventually wound up in the United States. With the fall of the Romanov dynasty, he joined a group of fellow political exiles intent on returning home and devoting themselves to the revolution. They left the East Coast by train for Vancouver, where they embarked on a ship to take them to Vladivostok and from there to Moscow by way of the Trans-Siberian Railway. Short, chatty, and something of a ladies’ man, George endeared himself to Fleming, and the two men got along splendidly during their travels throughout the province.

Their first stop was the town of Syzran, where they met with the local chairman of the executive committee, a Comrade Ageev, and an ARA-employed subinspector named Almazov, whom Fleming called an expert in uncovering embezzled American sugar and village committees not carrying out their duties. After a thorough examination of the books and some tea, Fleming was satisfied that everything was shipshape, and then he and George, accompanied by Almazov, left for the station and an overnight train to Gorodishche, the next stop on the tour. Given the many tales of railway bandits, the men slept with their shoes on. Fleming kept his Mauser pocket pistol at the ready.

The men got off the train at the village of Chadaevka in the early morning and climbed into a sleigh for the ride to Gorodishche, some dozen miles away. They raced across the heavily packed snow, exposed to an icy wind that froze their faces and cut through their clothing, and had to stop along the way at a peasant hut to warm up; three hours later they reached Gorodishche. The district of Gorodishche, roughly 210,000 people, had suffered terribly in the famine. Dr. Mark D. Godfrey of the ARA had visited in the summer of 1922 and found the conditions in the children’s homes to be especially deplorable. A free ARA medical dispensary was set up to help address the more than twenty thousand cases of trachoma in the area, as well as a plague of syphilis that afflicted 60 percent of the population.

The next morning, the men set off in two sleighs to inspect the surrounding countryside. Not taking any more chances with the cold, Fleming donned a twenty-pound sheepskin tooloop over his fur coat. The cloak’s collar extended several inches over his head, and the skirt reached to the ground; it was so thick and heavy that he required help to put it on and climb into the sleigh. Walking more than a few steps was out of the question.

They made slow progress, and soon it grew dark. The area was full of wolves, hungry for the taste of horsemeat, and so they kept on, in the hope of finding a place to put in for the night. Eventually, the lights of the village came into view. They made their way to the home of the village head, stabled their exhausted horses, and went in to warm up and get some much-needed food and rest.

Just then, a boy arrived to invite them to a wedding. Fleming wanted to beg off, but George insisted they go. The party was in full swing when they arrived. The room, filled with peasant girls and young men singing traditional folk tunes in high-pitched voices, fell silent as soon as the strangers entered, and every eye followed as they were shown to a large table covered with an assortment of salted fish, sausages, cabbage, fried meats, and a large tank. The head of the village held a dipper in his hand and began filling small tin cups that Fleming immediately recognized as retooled cans of ARA condensed milk.

It looked like water, but smelled like a mix of gin, three-in-one oil, and kerosene. George refused the cup offered to him, but Fleming graciously accepted. “My stomach did not object, but my tongue did,” he recalled. He didn’t dare light his pipe for fear his breath might ignite. When he had drained the cup, he returned it to his host with a large smile. “Tell them I could make a hundred miles to the gallon on that,” he said to George. Fleming began to fear the drink was affecting his eyes after he began to see black spots scurrying up and down the walls. But then he felt something move on his neck and looked down to see insects crawling all over his coat. The room was infested with vermin. Having seen enough, the two men got up, excused themselves, and left.

After inspecting the ARA kitchen the next morning, they set out with fresh horses for the Tatar village of Vyselki, where they arrived at twilight. It was a neat, peaceful-looking village—“the dream of a New England town,” Fleming thought. They rode up to the finest house, knocked, and were shown in by the owner, who proceeded to seat them before a steaming samovar. Their host then went to fetch the village head, the Orthodox priest, the Tatar mullah, and the members of the ARA committee. The mayor informed them that nearly all of the village’s five hundred inhabitants were relying on food substitutes to get by—millet husks, ground bark and bone, and lebeda. Although no one had starved to death that year, quite a few had perished the previous year. “Only the ARA rations saved the whole village from starvation,” he told them. As they went through the records of the ARA kitchen, Fleming treated the men to several cups of warm cocoa, which they drank with evident relish. Before the meeting broke up and the exhausted travelers prepared for bed, the mullah asked Fleming to do him the honor of visiting his mosque the next day.

A light snow was falling when Fleming and George were awoken in the morning and told the mullah had sent a sleigh to collect them. Melting the ice on the windows with their breath, they looked out to see a horse covered in frost. Icicles hung from its nostrils, and Fleming noticed how its frozen breath gave the poor beast the appearance of a skeleton. They stepped out into the cold. Columns of smoke drifted lazily from the village’s white chimneys. “For a second I did not feel it,” Fleming recalled. “Then a painful sensation developed around my forehead, eyes and nose, the only parts of my body exposed to the air. They seemed to be gripped by pincers.” The driver’s face was white with snow to match his steed. They set off at a gallop, the horse’s hooves shooting clumps of hard-packed snow at the men as they hurried to the mosque.

It was a large, barnlike building with a high roof and a spire finished with a crescent. The mullah met them at the door, explaining that he had postponed the service to await their guests. He led them upstairs into an expansive hall where about fifty men in Tatar robes stood, and then showed them to seats at the back of the congregation. With a sign from the mullah, the men dropped to their knees and prostrated themselves in the direction of the morning sun. The service lasted some twenty minutes, while Fleming and George watched with curious eyes.

Afterward, the mullah led one of the congregants up to Fleming. This man told him that during their ceremony they “had invoked the mercy and blessing of Allah upon the soul of the American Relief Administration and upon the American people for the good which they had done to this little town of Vyselki,” something they had been doing in their services for the past year and would continue to do as long as at least one of them was alive. He said to Fleming:

Without the American corn which we received last spring almost no one in this village would now be alive and standing here.

It seems wonderful that the great American people, so distant from us, should have heard of the little town of Vyselki and sent corn so many thousands of miles to us during the months of the famine. The authorities no further away than Gorodishche send us nothing, and did not even answer our entreaties for assistance.

Then he told Fleming that if they did not receive help again this year from the Americans, many more would die. “Can you help us?” he asked. Fleming assured him that he would speak to his superiors, but he could not promise that there would be any more food. Still, he wanted to do whatever he could for these people. “I like the Tartars [sic],” he remarked. “They seem like an intelligent lot.”

Fleming and George next traveled to the city of Penza, where they checked in to the shabby and run-down Grand Hotel. Since their room was too cold to stay in, they went off to the theater. The production was excellent, and George knew one of the actresses, so they invited her out for a drink after the play. Over a bottle of wine and cigarettes, Nadezhda Galchenko told them her tragic story.

Before the Great War, she had lived well in Kazan with her husband and children. They’d had a fine apartment, servants, and large landholdings in Ukraine, but lost everything in the revolution, and her husband was arrested by the Cheka as a counterrevolutionary. He was soon freed, and they fled to their former lands in Ukraine, where the peasants welcomed them back and gave them food. But the area became another battleground in the civil war, and again her husband was arrested. He was taken to Ufa and forced to join the Red Army. Nadezhda managed to meet up with him there.

“Ufa was a charnel house,” she told them. “The dead from starvation were more than the living could bury. Refugees from the villages wandered about the streets in desperation, searching for food, committing horrible deeds of violence at night—killing and stripping late pedestrians and selling their clothes in the marketplace for food.” To help feed her family, Nadezhda began acting in the theater. She won the favor of some Red officials, who gave her gifts of bread, meat, and cabbage. Then the Americans came, and they, too, helped the family with food. Eventually, they were permitted to move to Penza. Her husband had family here, and she managed to find work at the theater. And then, one day, her husband vanished. Though she wasn’t sure why he’d left them, she was not sorry to see him go. Sometime later, she married another man, who now worked as an inspector for the ARA. When she had finished her story, they sat in silence, smoking and eating chocolate. Then George escorted Nadezhda home.

Fleming found her beautiful and intriguing. He saw Nadezhda again, and soon thought he might be falling in love. He convinced her to leave her husband; sometime during that winter, she moved to Samara with her children to be near him. He would have her over to his room for dinner and then put a record on the phonograph and take her to his bed. In the early-morning hours, they’d dress, and Fleming would walk Nadezhda back home, while her children were still asleep. Young and naïve, he had no notion of what he’d done and how he was ruining Nadezhda’s life.

For the next three months, Fleming made a series of tours—back to Syzran and Gorodishche and Penza, as well as to Stavropol, Buguruslan, and Sorochinsk. The travel conditions remained brutal, with temperatures reaching minus thirty degrees Fahrenheit. Still, he loved it. One trip had him traveling for two whole days along the Volga, “a beautiful ride in sun and snow,” he wrote in a letter to his parents. He was taken with the vast treeless steppes that resembled the ocean. “The wind blows the snow into the form of waves, and for miles one sees about him only this restless rough expanse of snow like the surface of a bay under a small breeze—in one place a village stood out like an island, and the two domes of the church rose among the village huts on the horizon exactly like the twin lighthouses on Baker’s Island in Salem Harbor.”

Fleming encountered hunger and want nearly everywhere he went, but by April he had become convinced that conditions had improved markedly and the Russians should be able to pull through until the next harvest. Their work, as far as he could tell, was over.

PLEADING FOR FOOD, RUSSIA SELLS GRAIN

Petrograd Has 35,000 Tons Ready to Ship, Says American Relief Worker FAMINE MENACES 8,000,000

THIS WAS THE HEADLINE for The New York Times on February 21, 1923. The story was based largely on an interview with James B. Walsh, who had just returned home after serving with the ARA in the city of Rybinsk. He told the newspaper that he had learned about the grain while traveling through Finland on his way out of Russia. Over three thousands tons of grain had already arrived in Finland by rail from Russia, and he’d been told that Petrograd was making plans to ship thirty-five thousand tons in the coming months. The article went on to state that Mr. Walsh’s figures were likely too conservative, and that nearly one hundred thousand tons of rye, barley, and wheat from the Volga region had already left for Europe on ships from Odessa and Novorossiisk, on the Black Sea. According to official Soviet sources, there were plans in place to export as much as seven million bushels of grain that year.

The tone of the article left little doubt that the newspaper found this news incomprehensible, especially given that the ARA was still feeding one and a half million children a day and, according to at least one recent report, as many as eight million Russians would need to be fed before the end of the year. As justification, Kamenev was quoted as saying that the amount of grain being exported was small and only involved cereals that for a variety of reasons could not be used in the famine districts. Izvestiia later confirmed that roughly four hundred thousand tons of grain had been exported around this time.

The New York Times followed up on March 4, blasting what it described as “this preposterous movement of grain out of a country that has been facing famine and depending on foreign charity.” As to the reason for this action, the Times surmised that it may well have been an act of desperation, what it characterized as “the last card played by a government vainly trying to obtain resources to enable it to continue its exercise of power in the expectation that a world revolution may solve the deadlock between the Communist and the anti-Soviet governments of the world.”

In February, the Moscow correspondent for the Times, Walter Duranty, asked the questions on many Americans’ minds: “What is the real truth about the famine situation in Russia today? Has Russia a surplus of grain available for export? Is foreign relief needed to save millions from starving?”

Haskell was among those who both understood and endorsed the Soviets’ decision to export grain. The Associated Press reported on March 7 that Haskell had informed Hoover that what Russia needed now was not more famine aid, but credit or loans to rehabilitate its transportation and agricultural sectors. This article noted that Haskell had discussed the matter thoroughly with Kamenev, and both were in agreement that the country now had enough grain on hand to address the lingering famine, but Russia could not make a real step forward unless it received money from the West. Haskell had conveyed his thoughts to Hoover in a cable on the 6th, noting that, without greater economic assistance to the Soviet government, “misery and suffering by millions over a long period of years” would be a certainty. Hoover released to the press Haskell’s cable justifying the ARA’s decision to end Russian famine relief, but only after he had quietly excised Haskell’s comments endorsing Soviet grain exports and arguing for more general economic aid and cooperation.

Hoover’s underhanded attempt to control the story blew up in his face when one of the ARA employees in New York accidentally gave out the full text of Haskell’s cable to a reporter and it made its way to The Nation. “Mr. Hoover Stabs Russia,” the magazine accused on March 21, insisting that Hoover was grossly underestimating the need for further famine aid and trying to sabotage Soviet-American economic cooperation. Hoover’s anti-Bolshevism blinded him to the realities of Russian suffering and the basic needs of her people, the article stated.

Hoover stuck to his guns, however, and refused to back down on his decision either to end the mission or to recognize the Soviet government officially. Top ARA officials had held different opinions on these matters for some time, but up until then they had been kept private. Now the disagreements exploded into the open. Fisher and Herter sided with Hoover; Haskell and John R. Ellingston, director of the historical division in Moscow, opposed him. “Complete condemnation of [the Bolsheviks] and the spirit behind the revolution is, it seems to me,” Ellingston wrote to Fisher, “no more just, though just as natural, as British condemnation of the French revolution, and I suspect that no one in America in 50 years from now will regret the Russian revolution or feel that its big results were other than good.” Hoover and the ARA, in his estimation, suffered from “a lack of vision.”

The Soviet government handed Hoover and his supporters a gift later in March, when it put more than a dozen clergymen on trial for anti-Soviet agitation. The trial was a sham, and their guilt a foregone conclusion. All of the accused were sentenced to long terms in prison except Monsignor Konstantin Budkevich, a Catholic priest and an organizer of peaceful resistance to the seizure of church property, who was sentenced to death. The verdict unleashed an international outcry. Appeals for leniency poured in from political and religious leaders across Europe and the United States, including Pope Pius XI. All of these were brushed aside, and the Soviet prosecutor insisted that Budkevich had to pay for the clergy’s role in centuries of oppression of the working class. He was executed on Easter weekend, and his body disposed of in a mass grave. For Hoover, no greater proof of the Bolsheviks’ fundamental iniquity was necessary.

Confused about the conflicting reports coming out of Russia on the extent of the need for continued aid, Hoover had written in late January to Lincoln Hutchinson—one of his special investigators, then in Italy recovering from pleurisy—to ask him to go back to Russia and see what he could find out. Hutchinson, who had made a similar tour of the Caucasus with Frank Golder the previous year, replied that he was happy to do what he could, but that any information he might gather would amount to little more than “a new set of guesses.” He had noticed the past spring and summer how the Soviet authorities had cracked down on all efforts to conduct independent investigations into the food situation. Officials throughout the country had been given special orders not to hand out to foreign relief operations any statistics that had not first been sent back to Eiduk in Moscow for approval, and these orders had been followed with ever greater efficiency as the year progressed. Nonetheless, he promised to try his best, even though he held out little hope of coming back with any definitive answers.

In the meantime, the ARA moved forward with its plan to liquidate the operation. On March 1, Haskell wrote New York for authorization to begin the process, which he likened to a military mobilization that, once begun, would be difficult to undo or change in direction. The idea was first to stop all medical supplies, then the food-remittance program, next to close the remaining kitchens, and finally to shut down headquarters in Moscow and pull everything out of Russia. Their intention was not to inform the Soviets of this plan, in the hope of preventing them from causing trouble. Samovar diplomacy—the policy of appeasing Soviet demands wherever possible—would remain in force throughout the process. The goal was to avoid as many quarrels as they could and make the pullout smooth and uneventful. On the 13th, Haskell got the go-ahead from New York, aiming to get the ARA out of Russia by June 1.

On April 3, Hutchinson issued a report supporting the Soviet government’s officially stated view that the country now had enough grain, and corroborating its estimates for a large harvest. If hunger was to be a problem, he commented, then this would be due only to poor distribution, not to a serious shortage of food. The famine, he affirmed, was over. Two weeks later, the ARA released to the Associated Press an interview with Ronald Allen, district supervisor of Samara Province. He concurred with this growing consensus: “Samara, the blackest spot of last year’s Volga famine, is emerging from the catastrophe with an excellent chance of having a surplus of grain when the summer crop is harvested.” Allen said Russia would have no more need of the ARA after the first week of June, a view that was shared by the other district heads across Russia.

Hoover was delighted with the news. A State Department officer wrote to Secretary of State Hughes on May 4 of their recent conversation: “Mr. Hoover said that he had never been so glad to finish a job as this Russian job; that he was completely disgusted with the Bolsheviks and did not believe that a practical government could ever be worked out under their leadership.”

Haskell notified Kamenev of their intention to complete the liquidation in the first week of June. This didn’t come as a surprise: the Soviets had been aware of the general plan since late April. Once they knew, the Russians had started making things difficult for the Americans, just as Haskell had feared. They slowed down deliveries of food and supplies, and began stalling and dragging their feet. The less food the ARA dispensed to the hungry, the more that would be left for the government to confiscate.

On May 18, Lander sent a top-secret directive to all officials working with the ARA not to permit the Americans to take any photographs, films, or negatives with them out of the country unless these had first been inspected and approved by the GPU at the Moscow headquarters. A nervous inspector from Syzran came to speak in private with Ronald Allen in Samara and told him that orders were being sent out to the Russian personnel from Comrade Karklin to inspect the Americans’ bags, and to confiscate all cameras, binoculars, and firearms unless the Americans had special permission to leave the country with them. Every effort was to be made so that the ARA automobiles and trucks ended up in the possession of Posledgol, and every piece of “valuable literature”— regardless of the language it was written in—was to be seized. And, most important, they had been ordered to stop feeding operations and begin stockpiling as much American food as possible. When the inspector ignored this directive and continued to give out food, he was threatened with arrest. He managed to get away, and ran straight to Allen in Samara.

On June 3, the plenipotentiary attached to the ARA in Yekaterinburg Province, a certain Comrade Vilenkina, sent a secret letter to the regional representative chairman of the RSFSR* for the Bashkir Republic and Urals that showed just how poisonous relations had become. “The presence of the ARA in our Workers’ region is no longer desired,” she wrote. “I have secretly given out the order to confiscate all the Americans’ property immediately upon their departure.” According to the letter, the ARA had been giving out food parcels “left and right to prostitutes and suspicious persons.” Among the persons she singled out for special attack were Boris Elperine (“a provocateur [. . .] We must discredit him in the eyes of Bell”) and his boss, the Ufa district supervisor Bell (“an old geezer [. . .] a degenerate and a drunk”). In another letter, Vilenkina characterized the Americans as a bunch of unemployed war veterans who had come to Russia to make a profit off the Russian people; there wasn’t a humanitarian among them. They were to a man a drunk, unruly, debauched, and dishonest group. A few of them, she claimed, had raped women in Ufa and had to be spirited out of the country to avoid a scandal.

Lander sent a coded cable to Ufa as the ARA was preparing to leave, instructing officials there that any expressions of thanks must be of “an absolutely official nature.” He went on: “ Under no circumstances are there to be any large displays or expressions of gratitude made in the name of the people themselves.” In the case of Bell, however, this proved impossible. Everyone who knew Bell loved him. Elperine considered him “a master handler of men,” and Harold Fisher called him “a genius” who overcame more obstacles than anyone else in the organization. Olga Kameneva, the wife of Lev Kamenev and sister of Trotsky, who had also been involved in famine relief, agreed, saying he had done the best job of all the district supervisors.

Two happy Russian children eating their ARA rations in Ufa

Up until the last moment, Bell was working like mad to improve life in Ufa: organizing labor brigades to erect bridges, repair roads, and refurbish schools, and overseeing the reconstruction of the city’s glass factory, which, after he got it up and running, would employ five hundred workers. His efforts even won the praise of Pravda.

The people of the Bashkir Republic showered Bell with honors and gifts. He was made an honorary mayor of Ufa, honorary chairman of the Ufa City Council, and an honorary life member of the fire department of the town of Miass. People flocked to his office to present tokens of their gratitude, including six wolf cubs (which he had to politely decline) and a richly embroidered Bashkir costume presented by one of the Bashkir leaders. Bell was moved by this gesture. “I have lived with them through the worst period of suffering and hardship they have ever endured [. . .] They nursed me through typhus. I feel as though I am part of their new existence, and as they want me to come back and help them, I am determined to do so.”

Before catching the train back to Moscow for the last time, Bell called his young assistant, Aleksei Laptev, into his office and thanked him for all the wonderful work he had done for the ARA. He gave him a letter conveying the gratitude of the ARA and expressing his own personal desire to hear from him sometime in the future. Finally, Bell presented Aleksei with a gift: a brand-new American Underwood typewriter. It was a generous act, one that neither man knew at the time would change Laptev’s life.

In early May, Golder departed Moscow by train for Odessa, where he embarked on a U.S. naval vessel for Constantinople. About forty years earlier, Golder had made the same trip across the Black Sea, then as a boy fleeing the anti-Jewish violence of tsarist Russia with his family for a better life in America. His heart was breaking, and he was overcome with conflicting emotions as he sailed away from what he called “that sick country.”

As I stood on the destroyer looking over Odessa, tears almost came into my eyes at the thought of the misery and suffering endured by those big hearted and fine people and I felt so sorry for them. That, no doubt, is the feeling of every ARA man when he leaves Russia. Yet there is nothing more that we can do. We are leaving and that is right. We have done a monumental piece of work, for in addition to feeding the hungry we have started forces at work that are bound to have results. I do not feel like a deserter, but more like one who fights and runs away and will live to fight another day.

On June 13, the last ship carrying food from America arrived in Riga. On the 15th, a final liquidation agreement was signed by Haskell and Kamenev, stating that both countries were satisfied with the fulfillment of all promises and commitments by the two sides, including the payment of all moneys due the ARA by the Soviet government. The next evening, the ARA hosted a farewell banquet in Moscow, whose guests included Kamenev, Dzerzhinsky, Litvinov, Radek, and Lander. Haskell greeted everyone with a few brief remarks, thanking all of them, and especially Comrade Dzerzhinsky, for their energy and help over the past two years, and stating that the representatives of the ARA were now convinced that the Soviet government was working for the well-being of the Russian people and that no barriers remained to prevent America’s recognition of the USSR, something he hoped to see very soon.

Then came warm, grateful speeches by Kamenev and Radek in praise of America’s selflessness, altruism, and idealism. Chicherin captured the spirit of the evening when he said:

The work of the ARA is in fact the work of the entire American people, who came to the aid of the Russian people during hard times and in so doing set down a solid foundation for a future of unshakeable friendship and mutual understanding between us [. . .] In the name of future relations between the American and Russian people, which are sure to be both fruitful and rich, we honor today the mighty work of the ARA and, surveying the enormous scope, and future results, of its operations, we proclaim with all our hearts: Long Live the ARA!

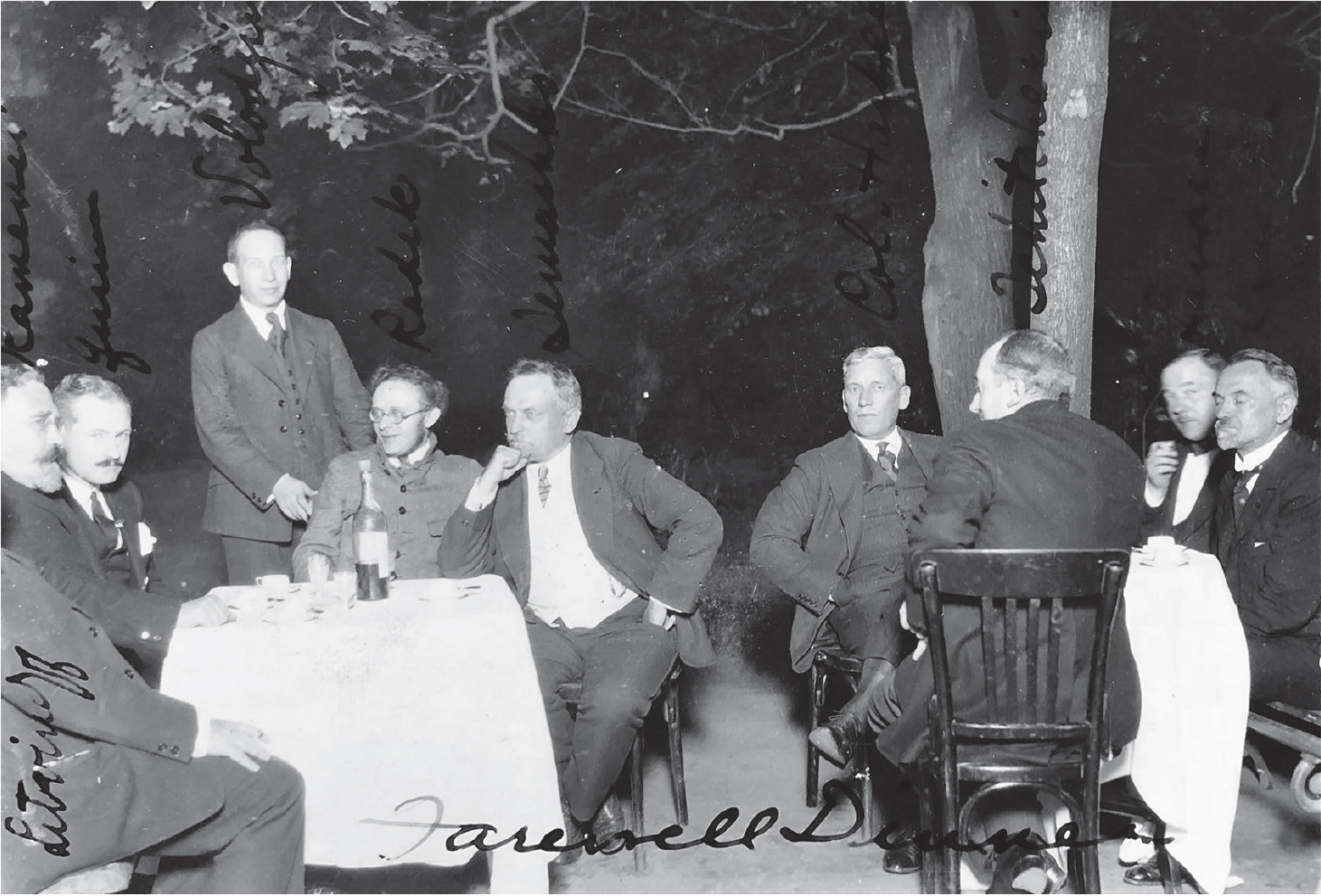

The Council of People’s Commissars reciprocated with a banquet for the ARA on July 18. It was a sumptuous affair for about fifty persons, the top ARA representatives and Soviet officials, plus members of the international press corps and foreign dignitaries. As the men feasted, an orchestra played behind a bank of potted palms. Coffee, liqueur, and cigars were served in the garden after dinner, and then the guests returned to the great state dining room for a round of speeches and toasts in recognition of the ARA’s monumental efforts, and expressing the firm belief of better relations to come between the two countries.

In the garden at the banquet on the evening of July 18. From left to right: Maxim Litvinov (largely obscured), Lev Kamenev, Cyril Quinn, Mr. Volodin (Lander’s secretary), Karl Radek, Nikolai Semashko, William Haskell, Georgy Chicherin, Karl Lander, and Leonid Krasin

Kamenev presented Haskell with a commemorative enamel plaque and then read aloud the official proclamation of gratitude from the Council of People’s Commissars:

During difficult times of enormous natural calamity, the American people, represented by the A.R.A., responded to the needs of a population, already exhausted by intervention and blockade, suffering from famine in Russia and the Union Republics, and unselfishly came to its assistance by organizing on the broadest scale the supply and distribution of food and other goods of primary necessity. Thanks to the enormous and entirely disinterested efforts of the A.R.A., millions of people of all ages were rescued from death, and whole towns and cities were saved from the horrible catastrophe that threatened them. Now, with the enormous work of the A.R.A. coming to an end, the Council of People’s Commissars, in the name of the millions who have been saved as well as the working masses of Soviet Russia and the Union Republics, is honor bound before the entire world to express its most profound gratitude to this organization, to its leader Herbert Hoover, to its representative in Russia Colonel Haskell, and to all its employees and to declare that the peoples of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics will never forget the help the American people showed them by way of the A.R.A. and recognizes in this help the pledge of future friendship between both peoples.

An emotional Haskell accepted the gift. “I am proud to say that I consider all of you my personal friends,” he told his hosts, “and part from you now not by saying ‘Farewell,’ but ‘Do svidaniya,’ until we meet again.”

The ARA had saved millions of lives. According to the Soviet press, it had fed eleven million people—almost a tenth of the population—in twenty-eight thousand towns and villages and distributed over 1.25 million food parcels. It had restored fifteen thousand hospitals serving eighty million patients and inoculated ten million people against a variety of epidemic diseases. No reliable records were kept on the number of famine victims; the estimates range from as many as ten million to as few as one and a half million. A reasonable figure would be over six million excess deaths from starvation and disease, making this one of the worst famines in world history, behind the Chinese famines of 1877–79 (over nine and a half million dead) and 1959–61 (over fifteen million) and the Indian famine of 1876–79 (roughly seven million excess deaths).* And how many lives did the ARA save in the end? This is even more difficult to answer, although, when one considers both food relief and medical intervention, an estimate of more than ten million does not seem exaggerated.

But it was more than just saving lives. The ARA had given the people hope. A thank-you note from one village in Samara Province expressed a sentiment shared by millions of other Russians, Ukrainians, Jews, Tatars, Bashkirs, Avars, Mordvins, and Udmurts: “Saving our children from death by starvation, you saved the future of our country. We may perish for our sins, but thanks to you, our children will grow up and make for themselves promising futures, not repeating our mistakes.”

In the spring of 1921, the Soviet government had faced daunting threats to its existence on a number of fronts. When famine erupted, and Soviet officials began to realize the horrifying dimensions of this fast-moving catastrophe, Lenin knew he had to turn to the capitalist West to save his communist regime. Several countries heeded the call, and every contribution was important, but America provided the lion’s share, some 90 percent of all relief. The ARA had helped to stabilize a country teetering on the edge of a precipice, and in so doing allowed the Soviet regime to consolidate its power.

On July 20, Haskell and the few remaining Americans in Moscow closed down the ARA headquarters and departed for home. They left not only with a deep sense of satisfaction at what they had accomplished, but also with a conviction that a new chapter in Russian-American relations had begun, one of friendship, trade, and cooperation, for which they could rightly claim no small role.

FLEMING LEFT SAMARA for Moscow on May 14. Three days later he boarded the Moscow-Vladivostok Express with plans to sail home across the Pacific from the Russian Far East. As his train pulled out of Moscow, he was overcome with emotion. Nadezhda had ridden the train with him part of the way from Samara to the capital, and it was only then that he realized the depth of her feelings for him. He had taken her talk of love as mere words, a sort of game they were playing with each other, and had given no thought to their future. At Syzran she left him, devastated at how she had misread his feelings for her. Fleming was a confused mess of emotions. On the 18th, an anguished cable arrived at the ARA office in Moscow from Nadezhda, addressed to Fleming: “Life intolerable. Death preferable. Telegraph.” Headquarters took the matter seriously. They sent a cable to Ronald Allen, still in Samara, and instructed him to find Nadezhda and see about the situation. It wasn’t that anyone at headquarters was especially concerned for her welfare; rather, the ARA felt that everything possible had to be done to avoid a scandal.

Fleming changed his plans while crossing Siberia, and at Chita, on the far side of Lake Baikal, he boarded a train for Peking. He found that he was not ready to return home, and wanted to see if there wasn’t some chance of getting back to Russia. “I was never so homesick in all my life as I was for Russia when I left it,” he wrote a friend back in the States in mid-August. Just writing the date of his departure from Moscow he found painful. Their train had passed by the monastery at Sergiev Posad, north of the capital, and seeing its towers and domes brought back memories of a visit there one moonlit night the previous summer with Paulina. He couldn’t stop thinking about her, and was awash in regret for not having asked her to marry him. He managed to get by as a freelance reporter in China, but all the while his thoughts were directed toward Russia. Throughout the rest of the summer and on into the autumn, he sent out application after application for any sort of job in Russia, but nothing came through. He tried to get a position at the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, in the hope this might offer some opportunity to go back, but the job never panned out. The end of December found him in Shanghai, writing for a local newspaper and waiting for a Soviet visa that had been held up for a month. “I dreamed the other night that I was in battered old Samara,” he wrote his parents, “looking for Nadezhda Mikhailovna but in vain.” He received a handful of letters from Paulina and Nadezhda, but then these, too, stopped coming.

Fleming never did get a Soviet visa. By March 1924, he had run out of money and hope. Nothing was going his way. The articles on his experiences in Russia that he’d been submitting to newspapers and magazines in the States kept coming back in the mail with rejection letters. His writing, one editor commented, “lacked exactness.” He left Shanghai that month on the Empress of Asia, sailing for Vancouver, and from there went south by train to Seattle. When he checked in to the Sigma Chi fraternity at the University of Washington, he found a letter waiting for him from Arthur T. Dailey of the ARA. Dailey had written to inform him that his query about being hired back on had been received, but, unfortunately, at this time the ARA no longer needed his services.

Fleming moved to New York City, found work as a financial journalist, and later married. A decade later, he was still struggling to get over Russia. He tried to fill this hole in his life through his work as editor for the quarterly A.R.A. Association Review, a position he held for thirty years. He contributed this notice in 1932: “Wanted: By a number of former ARA relief workers. A famine, earthquake or pestilence. In going condition. Guaranteed to run indefinitely, or until Prosperity gets around the corner.” Twelve years later, he wrote in the review that he was still living on Washington Square with the “same wife, same cat, same typewriter, same pictures on the wall.” Nothing could take the place of his Russian adventure.

Fleming always looked forward to the annual ARA reunions held in New York at the Harvard Club or Waldorf Astoria Hotel. He was there for the last one, on April 24, 1965. Times had been hard for Fleming of late. His wife had died a slow, painful death that had almost destroyed him. For nearly a year, he’d lived on little more than whiskey. He would have gone on drinking, but his liver finally gave out, and he had to get off the bottle. Seated next to him at that last reunion was Aleksei Laptev. A few years after the ARA left Ufa, Laptev traveled to Moscow, bringing with him the expensive American Underwood typewriter that Bell had given him before departing. He found a hard-currency store willing to buy it from him for a good price, and with his newfound wealth he bought himself a one-way ticket on an ocean liner to America.

That night was Holy Saturday, the day before Easter, the most sacred time of the year in the Russian Orthodox calendar. When Laptev mentioned this to Fleming, he saw his face light up at the memory of the holiday in Russia some forty years before. He invited Fleming to be his guest at the midnight service, and the two men walked out of the Waldorf together. They joined the clergy and congregation as they made their procession around the church, candles in their hands. Afterward, Laptev brought Fleming back for the Easter meal with his small circle of family and friends. It was the last time they ever saw each other. Fleming died in 1971.

RUSSIA HAUNTED MANY of the ARA men, not just Fleming. The experience had been difficult, frustrating, at times even dangerous, but it had also been profoundly rewarding, intense, and meaningful, and it had made them feel important. In Russia, they were big men, rich and powerful, exotic and alluring. Back in the States, they were just regular Joes again—no big deal, nothing out of the ordinary. The transition wasn’t always easy.

In September 1923, while vacationing in Savoy, Bell wrote to a fellow ARA veteran, R. H. Sawtelle: “I found that the Russian experience had pretty well knocked me about physically, which was not strange when one considers what Ufa did to me in the way of typhus, rheumatism and malaria.” Regardless, it remained the best thing he’d done in his life: “My association with the ARA has always been the greatest pleasure and satisfaction of anything I have ever been connected with and the spirit of loyalty shown throughout the entire organization, as exhibited by the difficult and dangerous work in Russia, where the only motto seemed ‘Carry on’ made it a greater honor to have been part of the organization.” A month later, Bell was busy trying to find a way to go back to Russia as soon as possible and get involved in some sort of business venture. He was excited by what he’d been hearing about the changes there. It seemed that a new “light,” as he called it, was emanating from Moscow.

Bell never made it back. He settled in Danbury, Connecticut, and got a job with the American Hotel Corporation. Ufa never left his thoughts, however. Later, he helped raise a fund among his ARA colleagues to help bring their dear old comrade Boris Elperine to New York City. Bell died, aged seventy-two, in 1946.

In the summer of 1922, William Kelly took a room at the Harvard Club on New York’s West Forty-fourth Street and began looking for work. Unlike his old boss, Kelly hadn’t the least desire to return to Russia. His job inquiries at Doubleday, Page & Co. Publishers, Funk & Wagnalls, and the U.S. Department of Commerce went nowhere. Even though money was tight and his prospects were not looking bright, he and Jane decided to go ahead and get married, and eventually Kelly found a position with an advertising agency on Madison Avenue. He remained in advertising for the rest of his life, and died in 1977 at the age of eighty-one.

Childs returned to Lynchburg with Georgina in the spring of 1923. He sat for the Foreign Service examination, and then received word he’d been hired by The Christian Science Monitor as their Moscow correspondent. The couple’s Soviet visas were issued, and they were all set to leave when Georgina had a change of heart. There was simply no way she could go back. Given what she’d been through, and what awaited them, Childs understood, and he informed the newspaper he’d not be taking the job after all. That autumn, Childs joined the State Department and began what would become a thirty-year career, with postings across the Middle East and Africa, including ambassadorships to Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia. Upon his retirement, he and Georgina settled near her mother in Nice, France, in an apartment with a view of the sea. Childs never gave up on his dream of a literary career; he penned a couple of adventure novels and established a reputation as one of the world’s leading authorities on Casanova. Georgina died in 1964, and eleven years later Childs took her ashes home with him to Lynchburg so they could be buried together. In 1975, he made one last trip to the Soviet Union. Upon his arrival, Childs mentioned to an airport official that he had been in Russia fifty years earlier with the ARA. The man’s face lit up. “Ah-RA,” he whispered with reverence. That one moment made the entire trip worthwhile. Twelve years later, Childs died of heart failure in Richmond, Virginia. He was ninety-four.

Frank Golder arrived back at Stanford in the autumn of 1923 in time to begin teaching his classes on Russian history and to start the arduous task of sorting and compiling the vast collection of books, periodicals, and ephemera that he had acquired in Russia for the Hoover War Library. Immersed in Russia’s recent past, he soon struck upon the idea of creating an institute for the study of the revolution that would bring together American and Soviet scholars in joint research projects.

Together with Lincoln Hutchinson, Golder traveled to the USSR in late 1927 to try to interest the Russians in his plan for a research institute, and to witness the celebration of the ten-year anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution. Life, he observed, was still a struggle, and ragged orphans still filled the streets, but food was plentiful, and a sense of normality had returned. The big cities showed undeniable evidence of a material prosperity that had been lacking when he’d left four years earlier. He witnessed the military review and listened to the speeches on Red Square on November 7. The scene called to mind moments of his past: 1914, when he’d seen Tsar Nicholas II bless the army on the eve of World War I; 1917, when he’d listened to Alexander Kerensky, head of the Provisional Government, exhort the troops to keep up the fight against the Germans; and 1923, when he’d watched Trotsky review the victorious Red Army. Today’s celebration seemed monotonous and uninspired, as if everyone was simply going through the motions. “How the mighty have fallen and how much blood has been wasted in those thirteen years!” he wrote. “How little there is to show for it!”

The visit convinced Golder that the Soviet Union was moving ever further away from communism. “The Stalin progressives,” he told a gathering of ARA alumni in New York City upon his return, were defeating the party of Trotsky, which would mean the abandonment of “the sacred tenets of the revolution.” Soviet Russia now realized its fate lay with the West and the investment and credit it alone could provide, he assured his former colleagues.

As for his institute, matters hadn’t gone as Golder had hoped. After reviewing one of the initial manuscripts, Soviet officials took umbrage at how the authors had depicted the Bolsheviks’ treatment of the peasants, and expressed serious doubts about the advisability of a scholarly body that tried to combine what they believed to be outdated Western bourgeois history with their more advanced scientific school of Marxism-Leninism. Such theoretical concerns became moot a few years later, when most of the scholars Golder had wanted to work with were imprisoned under Stalin. Golder himself died in January 1929 after a brief illness. It was perhaps something of a blessing that he did not live to see his beloved Russia descend into the dark madness of Stalin’s terror.

GOLDER WAS NOT the only American convinced of Russia’s bright future. “Communism is dead, and Russia is on the road to recovery,” Haskell wrote to Hoover in late August 1923, after returning to the United States. “The realization by the Russian people that the strong American system was able and contained the spirit to save these millions of strangers from death that had engulfed them must have furnished food for thought [. . .] To America, this is a passing incident of national duty, undertaken, finished, and to be quickly forgotten. The story will be lovingly told in Russian households for generations.”

Haskell, of course, was wrong. Communism was not dead, and Russia, or at least official Russia, was soon looking upon this experience with the ARA in less-than-loving terms.

The first arrests appear to have begun not long after the Americans’ departure in July 1923. The GPU arrested a former nobleman by the name of Palchich who had worked for the ARA and accused him of being a spy and having provided the Americans with secret maps of the Baku oil fields for use in a planned American invasion. A certain N. Belousov, the son of a tsarist officer and an inspector for the ARA in Simbirsk, was arrested; he purportedly admitted under questioning that his anti-Soviet views had led him to cooperate with American agents embedded in the ARA. Among his supposed crimes was gathering information for the ARA on the economic conditions and food supply in one remote district. One of Childs’s assistants, a woman named Molostova, was also imprisoned as an agent of the United States. Proof of her treachery was that, upon Childs’s request, she had translated Russian books about the Soviet economy and agriculture.

In May 1924, under the headline “ARA Spies in Role of Philanthropists,” Izvestiia reported the arrest of two Soviet citizens on charges of economic espionage. One of them was sentenced to ten years in prison; the other, five. Hoover was outraged. “While the imprisonment of those assistants continues,” he told the press, “it will form an impassable barrier against any discussion of the renewal of official relations.” Secretary of State Hughes agreed with Hoover, as did first President Harding and then his successor, Calvin Coolidge. Official recognition of the Soviet Union would have to wait another decade, until November 1933, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt established normal diplomatic relations between the two countries.

Although this recognition did not come until a full decade after the end of the ARA mission, relations between the Soviet Union and the United States had not stagnated during the 1920s. Just the opposite. Harding and Coolidge, with the support of Hoover as secretary of commerce, may have opposed official relations, but they did nothing to prevent American firms from doing business in Russia, and even began to encourage them. Between 1923 and 1930, the sale of American goods to the USSR grew more than twentyfold, from $6 million to $140 million per year, and overall trade between the countries during that period surpassed $500 million, most of which consisted of American exports to Russia. A quarter of all Soviet imports came from the United States, representing a range of products but especially heavy equipment for use in mining, agriculture, construction, metalworking, and the oil-and-gas industry. Large credits flowed into the Soviet economy from banks such as Chase National, Guaranty Trust, and Equitable Trust and firms such as General Electric and the American Locomotive Sales Corporation, especially after Hoover lobbied the administration to loosen restrictions on private loans. By 1928, American companies were offering Moscow large, long-term financing deals, as much as $25 million over five years. Trade with the United States surpassed that with countries such as Britain, which had signed a trade pact with the Soviets in 1921 and established diplomatic relations three years later.

Trade and loans, however, had not convinced the Soviets to embrace capitalism or to forsake communism, as many Americans had believed they would. The logic of the Soviet Union’s internal development proved resistant to external influence. Haskell visited the Soviet Union in 1931, during the first Five-Year Plan. The country was in the midst of Stalin’s “revolution from above,” intending to erase all traces of capitalism and build the world’s first fully socialist state. Stalin had launched the USSR on a gargantuan program of crash industrialization. Bewildered at what he saw, Haskell only now began to entertain doubts about Russia’s future. “The people are allowed what the government prescribes—and nothing more—whether it be shelter, food, or clothing,” he noted. “Russia is at war; she is fighting a five-year battle against her own backwardness [. . .] The sacrifices that the people are making stagger the imagination.”

Forced collectivization of agriculture was the second pillar of Stalin’s revolution. Haskell toured the Russian heartland and spoke with the peasants. They admitted to being confused about what was happening and what the future held for them and their traditional way of life. They were worried, and suspicious of the government. Haskell shared their fears. “The kulak still remains earmarked for elimination ‘as a class.’ His ‘crime’ was that he got along fairly well.” By American standards, he’d be considered “a poor wretch,” but since he’d managed to raise his head just above the masses, it was to be “cut off.” Haskell asked the Russians he met what they remembered of the ARA. Most had never heard of it, and those who had wanted to know if it was true that the Soviet government, not the Americans, had paid for all the food.

Collectivization amounted to a new war against the peasants, eerily reminiscent of the bloody violence of a decade earlier. The state planned to ensure a surplus of grain, both to pay for industrialization and to feed the growing number of workers in the cities, by forcing the peasants off their individual plots and into large state-controlled collective farms. This second serfdom was met with fierce resistance in the countryside, and millions of people were deported to Siberia and other lands far to the east. The chaos resulted in another epic famine, in which at least five million perished between 1931 and 1934. Once more, the starving, driven mad by hunger, resorted to eating human flesh. But this time there would be no appeal for relief from the outside world.

By the early 1930s, Hoover was in no position to come to Russia’s aid even if he’d been asked. America’s great humanitarian had become a national hero after his exploits in Belgium and then Russia, and so, when, in the spring of 1927, heavy rains caused the Mississippi River to burst its levees and unleash a flood that destroyed one hundred thousand homes and displaced over six hundred thousand people in several southern states, it was only natural that President Coolidge looked to Hoover to head the relief effort. Working with the American Red Cross, Hoover directed one of the largest fund-raising efforts in U.S. history to bring food and supplies to the area. Although the operation was in large part successful, horrible atrocities were inflicted on African Americans. Denied the decent food and shelter provided to white American refugees, blacks were forced to live outdoors, amid miserable conditions. They did most of the difficult work in the immediate aftermath of the flood, under the watch of armed National Guard troops. Men who tried to rest were beaten. White planters feared African Americans would leave the area for the North, thus depriving them of cheap labor, so the white troops, and local law enforcement, placed many of them into what Hoover himself called “concentration camps” and forced them, at gunpoint, to remain. The exact number of African Americans murdered is still unknown.

Hoover enlisted the press to cover up the scandal and present a false picture of the relief operation as one of racial harmony and cooperation. He wished to avoid a scandal during his run for the presidency, and wanted to squeeze as much positive publicity out of the disaster as possible, even going so far as to commission the first-ever presidential campaign film— Master of Emergencies. Riding the wave of a booming economy, Hoover won the 1928 election in a landslide.

The stock-market crash of 1929 and ensuing Great Depression proved Hoover’s undoing. The “Master of Emergencies” now became the face of poverty and ineptitude. The shantytowns that sprang up in cities across America were dubbed “Hoovervilles”; the homeless tried to keep warm under “Hoover blankets,” old newspapers; cardboard inserted into worn-out shoes was “Hoover leather.” Hoover had not caused the economic calamity, but he’d also not been able to end it. To most Americans, Hoover seemed distant, aloof, untouched by the suffering of his fellow citizens. To others, he was downright cruel. Promising to defend American jobs for so-called real Americans and to remove the burden on relief agencies of what many considered the undeserving poor, Hoover and his administration organized the forced deportation from the United States of persons of Mexican descent. The Mexican repatriation—a form of ethnic cleansing—resulted in the expulsion of perhaps a million people, over half of them legal American citizens. Needless to say, the policy did nothing to end the Depression. Hoover lost the 1932 election to Roosevelt in a bigger landslide than his victory four years earlier. Even his home state of Iowa and adopted home of California went for Roosevelt. Hoover’s failure as a president erased all of his earlier successes.

Back in the USSR, the history of the ARA was being expunged or distorted beyond recognition. Workers took down the signs outside the Blandy Memorial Hospital and the Blandy Children’s Home soon after the ARA pulled out of Ufa. If the proposed monument to Blandy was ever built, it’s no longer there now. In Odessa, the Haskell Highway and Hoover Hospital were quietly renamed. Several of the officials with whom the Americans had worked and who knew the truth about the ARA’s mission fell victim to Stalin’s terror in the late 1930s. Kamenev, Radek, Eiduk, Lander, Kashaf Mukhtarov, Rauf Sabirov—all were executed as enemies of the people. Trotsky was butchered on Stalin’s orders in Mexico City in 1940. Olga Kameneva was shot in a grove outside Orël in 1941. A few managed to escape a violent end. Dzerzhinsky dropped dead of a heart attack in the Kremlin in July 1926 after delivering a fiery speech denouncing his old comrades Trotsky, Kamenev, and Zinoviev. Georgy Chicherin died a decade later of diabetes. Gorky died a month before, in June 1936. Rumors have long persisted that he had been killed on Stalin’s orders. Doctors removed Gorky’s brain and deposited it in Moscow’s Brain Institute alongside Lenin’s and those of other exceptional figures, so that researchers could dissect it in their search to uncover the material basis of genius.

There was no statute of limitations for the crime of having worked for the Americans. In 1948, a full quarter-century after the ARA left Russia, a man by the name of Gorin was arrested as an American spy. During his interrogation, he confessed that he had first been recruited by Blandy in August 1921 as part of a plot to overthrow the government. He had gathered sensitive information for the Americans and divulged the identities of the Russian staff working for the GPU. He also told them that the Americans had not given up their nefarious plans. Just last year, he said, Colonel Haskell’s son had visited Moscow and had tried to get in contact with former Russian personnel of the ARA. It required no further comment that the purpose of his visit had been to reinvigorate the anti-Soviet operations begun by his father.

The rhetoric against the ARA heated up during the Cold War. According to the 1950 edition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, the ARA had been established solely “to create an apparatus in Soviet Russia for spying and wrecking activities and for supporting counterrevolutionary elements.” Not a single reference was made to the Americans’ relief operations. A standard history textbook from 1962 explained to schoolchildren that Hoover had sent the ARA to Soviet Russia “to secretly organize an insurrectionary force,” but thanks to the vigilance of the Cheka and GPU, his plot was uncovered, the ARA’s Russian counterrevolutionary agents were arrested, and America’s plans to overthrow the first communist government were thwarted.

In 1958, Izvestiia attacked Hoover after he spoke at the Brussels World’s Fair: “It was he who headed the notorious American Relief Administration, which so shamelessly covered its relief to all and sundry enemies of Soviet rule with its alleged concern for the hungry.” The following year, on a visit to the United States, Nikita Khrushchev was willing to admit that, even if, thanks to the ARA, “thousands of people were rescued from famine on the Volga,” the world should remember that it was American intervention that had brought about the Russian civil war and thus the famine. “American aid?” he sneered. “You have to sell your soul to get it.” Hoover found the vilification hurtful. “My reward was that for years the Communists employed their press and paid speakers to travel over the United States for the special purpose of defaming me,” he wrote in his memoirs.

Although Russia had turned her back on Hoover, one place where he could always count on getting a warm reception was the annual reunion of ARA employees in New York. He was a regular speaker at these events, and the men, now old and gray, loved nothing more than to listen to The Chief recount the tale of their glorious mission to Russia. Hoover continued to attend the reunions for decades, until his death in 1964.

Moscow, March 14, 1922, noon. Four girls enjoying their meal of bread, rice, beans, and cocoa outside the ARA kitchen in the old Hermitage Restaurant. The ARA provided lunch for four thousand children at this one location every day.

The mission of the American Relief Administration was not the last chapter in the history of American aid to Russia. Under the Lend-Lease program, signed into law by President Roosevelt in March 1941, the United States delivered $12 billion in supplies to the Soviet Union between 1941 and 1945 to support the war against Nazi Germany. Along with matériel, which included 15,000 airplanes, 9,000 tanks, 362,000 trucks, and 15.4 million pairs of army boots, America shipped millions of tons of food (powdered eggs, grits, dried peas and beans, coffee, sugar, flour, and Spam), which by 1945 amounted to 10 percent of the entire agricultural output of the Soviet Union.

During a ballet performance at Leningrad’s Mariinsky Theater in October 1954, the New York Times reporter Harrison Salisbury met a middle-aged survivor of the nine-hundred-day siege of the city. Salisbury asked the man what Russians thought of Americans and whether they recalled their help during the war. “Of course we remember,” he said. “American Spam . . . we still make jokes about it but we were glad to eat it at the time. American butter . . . American sugar . . . We haven’t forgotten that America helped us. We Leningraders never forget a friend.”

The official government attitude, however, was to play down American help. Not everyone went along. Marshal Georgy Zhukov, the brilliant Soviet military commander, insisted on acknowledging the significance of Lend-Lease: “Now they say that the Allies never helped us, but it can’t be denied that the Americans gave us so many goods without which we wouldn’t have been able to form our reserves and continue the war.” American support had been crucial in sustaining the Soviet struggle against the Nazis.

The United States came to Russia’s aid once more in the 1990s, when the collapse of the Soviet Union led to severe economic hardship. Millions lost their jobs or went without pay; basic necessities were in short supply; the stores were empty of food. In 1993, 70 percent of Russian households were experiencing hunger. By the end of the decade, almost half of the population was living below the poverty line. The United States, together with Western Europe, stepped in to help. Between 1992 and 2007, the U.S. government provided $28 billion in assistance to the countries of the former Soviet Union. In 1999 alone, Russia requested five million tons of food aid from the United States, worth nearly $2 billion. The European Union added several hundred million dollars’ worth of food assistance as well. For 1999–2000, U.S. and European food aid to Russia surpassed that given to the entire continent of Africa.

IN “THE AMERICAN CENTURY,” published in Life magazine in February 1941, Henry Luce wrote that Americans had “to accept wholeheartedly our duty and our opportunity as the most powerful and vital nation in the world and in consequence to exert upon the world the full impact of our influence.” With the world at war, it was no time for Americans to be gloomy or apathetic. He urged the United States to take up its role as “the Good Samaritan of the entire world” in words that echoed the spirit of Woodrow Wilson two decades earlier.

According to Luce, it was not just power that made America exceptional, it was her values as well. “We are the inheritors of all the great principles of Western civilization—above all Justice, the love of Truth, the ideal of Charity.” Americans, he argued, had a sacred duty to use the nation’s great might to lift “the life of mankind from the level of the beasts to what the Psalmist called a little lower than the angels.”

Luce’s idea of the American Century was always more aspirational than real, and it is a mistake to think that America still exerts the kind of global power it did in the second half of the last century. Just as America’s power has waned, so, too, has Americans’ belief in the fairy tale of their ability to redeem the world, which can only be seen as a change for the better. Nonetheless, even if the United States can’t be the world’s Good Samaritan, Americans should never forget that their country possesses enormous wealth that can do much to relieve suffering throughout the world. A century ago, Maxim Gorky praised the generosity of the American people “at a time when humanity greatly needs charity and compassion.” May the story of the ARA inspire that same spirit of generosity today toward all humanity, abroad and at home.