The Tale of the First Adventure

By Derrick Belanger

This story first appeared in the MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories Volume IV.

Derrick Belanger is an author, publisher, and educator most noted for his books and lectures on Sherlock Holmes and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. A number of his books have been #1 bestsellers in their categories on Amazon.com including Sherlock Holmes: The Adventure of the Peculiar Provenance, Sherlock Holmes: The Adventure of the Primal Man, MacDougall Twins with Sherlock Holmes: Attack of the Violet Vampire!, and both volumes of his two volume anthology A Study in Terror: Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Revolutionary Stories of Fear and the Supernatural. Mr. Belanger is co-owner of the publishing company Belanger Books which has reissued new editions of the August Derleth Solar Pons books as well as publishing new Solar Pons story collections. His academic work has been published in The Colorado Reading Journal and Gifted Child Today. A former instructor at Washington State University, and a current middle school Special Education teacher at Century Middle School in the Adams 12 School District, Derrick lives in Broomfield, Colorado with his wife Abigail Gosselin and their two daughters, Rhea and Phoebe. Find him at www.belangerbooks.com and http://belangerbooks-sherlockholmes.blogspot.com/.

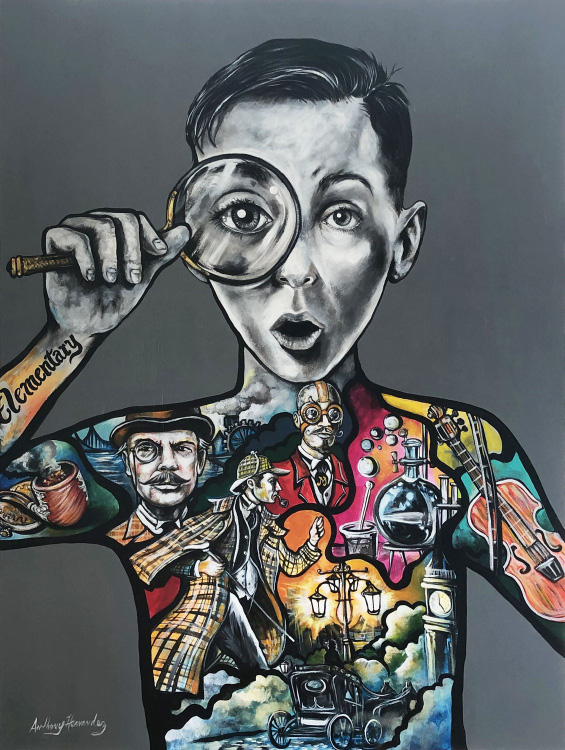

Anthony Hernandez was born in Havana, Cuba on October 16, 1972. His love and passion for art influenced his life as a young child. Anthony was fascinated by works of artists from his birthplace including Amelia Peláez, Mario Carreño and Rene’ Portocarrero. At the age of 12 he immigrated to Chicago and now resides in Florida. His work is predominantly in the medium of acrylic paintings on canvas and murals. Anthony is a firm believer that everything is somehow connected: “Our actions and our intentions, whether good or bad, create a chain reaction. Each work or piece in any medium I use will carry that message of connection. I always emphasize that art and life go hand in hand; it is about decisions not conditions”.

Artwork size: 36” × 48”

Medium: Acrylic on canvas

It was with exciting news that I hurried to 221b Baker Street one late autumn afternoon. I had just received an unexpected patient, and the man came with information about my dear friend Sherlock Holmes. The man, a Mr. Zenas Cooper, had arrived at my doorstep supporting his back with a well-worn wooden cane. He had injured himself in the process of lifting a large trunk of clothing, and was afraid he had caused serious damage. His brother, Tobias Cooper, a regular patient of mine, had recommended Zenas see me before his long ride back to Devon. After a few tests, I could see that my initial diagnosis, that Mr. Cooper had strained his lumbar, was accurate. I assured the man that while the pain and discomfort were debilitating, if he rested and stayed off of his feet, he would be healed within a week’s time.

Mr. Cooper was a good twenty years my senior. A large man with ruddy cheeks, wispy white hair, emerald eyes, and a jolly laugh, he was in good spirits despite his situation and said he felt blessed that his wife had packed his cane on his London sojourn to visit his brother. Just as he completed his visit and I assisted the man to the front door, he paused and asked in his booming voice, “Say . . . I think . . . no, no, I’m sure it is a coincidence.”

I inquired as to what the gentleman was puzzling about.

“You wouldn’t happen to be the same Dr. Watson who wrote that story in Lippincott’s? . . . The Sign of the Four, I believe it was called.”

I assured him that I was, and the man let out such a bellowing laugh that for a moment I thought he had become Dickens’ Ghost of Christmas Present. “My good man,” he started, “you tell Master Holmes, for he will always be Master Holmes to me, that Mr. Cooper still remembers the good turn he did for me, and that I am and will eternally be grateful.”

I asked the man whatever Holmes had done for him, and his face brightened to an even warmer shade of red. “Why, Master Holmes saved my marriage, the lad did. Bright boy. Exceptional, really. The top student I ever taught in my first year class. Suppose with Master Holmes, it’s hard to say how much I taught him and how much he taught me. I could tell you more, but I am afraid I have a train to catch. Please do give Master Holmes my kind regards, and ask him about the good turn he did for Mr. Cooper. You’re Dr. Watson, after all. You’d want his telling of the events if you see fit to turn the tale into one of your publications. I’m sure I’d miss some of the important details for it was so long ago, but that Master Holmes, with that brain of his, even though he was just eleven at the time, I’m sure he remembers every detail.” And with a wink, he hobbled off down the steps to his awaiting taxi. I assisted the man into the cab, and no sooner had his left then I hailed one myself, for with this information, curiosity had seized me. Mr. Cooper had been my final patient for the day, and I knew Mrs. Watson was visiting a friend for the afternoon and wouldn’t return until early in the evening. I just had to see Holmes, had to know about this mystery he’d puzzled out at such a young age.

As the hansom pulled up in front of 221b Baker Street, I nearly leaped out of the cab. I found the door to my friend’s residence unlocked and practically flung it open. Fortunately, Mrs. Hudson was not at home, for I’m sure she would have scolded me for not knocking before entering. Not tarrying a moment, I bounded up the seventeen steps to Holmes’s sitting room as fast as my legs could carry me. When I was almost at the top of the stairs, a sharp jolt of pain shot through my left leg, which still suffered from a wound I’d received from a Jezail bullet in the Afghan War. I gave out a holler, winced, and cursed myself for my over-ambition. Using the railing of the stairs, I supported myself and limped up to the door of the first floor rooms. I didn’t bother knocking, but with a swift turn of the knob swung the door wide and found Holmes in his armchair, reading over several papers with a magnifying glass.

“Watson,” he said, barely taking his eyes off of the document he was inspecting, “it appears that the ransom letter to the Australian businessman Robert Steele was not written by his daughter, but rather by his wife. The curl of the q and the curve of the g are quite definitely the same.” He lowered the papers and motioned for me to sit down. “Now then, please have a seat, get off of your foot, and tell me about this patient who had knowledge about my past.”

“Really, Holmes,” I groaned, collapsing into my favorite chair. I pulled the hassock to me and raised my injured leg upon it. I could tell the pain would go away with the passage of time and rest. “How, even with your powers of observation, could you have known about the gentleman who visited me this afternoon?”

“None of my so called powers is beyond those contained by every person in this fair city. I simply observe, analyze, make logical connections, and draw my conclusions based on the evidence presented,” Holmes stated matter-of-factly. “Now, if you’ll excuse me for just a moment.” He gathered the papers he had been examining, stood, and took them to his desk. With a quick stride, he then went to his spirit case and returned to his seat carrying two glasses of brandy. He handed one to me, for which I thanked him.

“We need to make sure my Boswell does not overexert himself. Now, my dear Watson, tell me about this unexpected patient of yours.”

“Not quite yet, Holmes. First you must tell me how you knew my patient was connected to your childhood.”

“Really, Watson, that is quite elementary,” he said and took another sip of his brandy. “Look at the time of day. You practically sprinted up the steps to tell me some exciting news. Me, not your wife, for clearly you did not have enough time to see Mrs. Watson after your hours ended and then come to Baker Street. You must have left your practice in great haste, for you did not notice you still wore the stethoscope around your neck. Indeed, you still do.”

Here, I paused and checked myself. The stethoscope was indeed upon my person. In my hurry and excitement, I did not even notice. With a look of embarrassment, I took off the device and placed it in my coat pocket.

“You see,” Holmes chuckled. “So, what would cause my good friend to dash off to visit me? Was it something negative, a warning perhaps? Certainly not with the high spirits you exuded, even with your reinjured wound. So, therefore, it had to be something exciting. But what did you discover that could not wait until this evening or even the weekend to tell me? It had to be something particularly extraordinary, and the conclusion, from the time of day of your visit along with your garb, is that it was a patient who brought you such information. Since only yesterday you were asking again about my past, particularly my childhood, the logical conclusion is that you met someone from then who revealed some part of my history from before we met. Am I correct?”

“You are, Holmes, in every aspect.” But here it was my turn to crack a wicked smile. “But, you do not know who it is that visited me.”

Holmes let out one of his odd silent laughs and held up his lanky right arm, tsking me with his pointer finger. “There is only so much I can deduce with the data provided. But tell me, my good man, who was this unexpected patient?”

“His name,” I said through gritted teeth for my injury flared up again, “is Mr. Zenas Cooper.”

At the mention of Mr. Cooper’s name, a strange change came over my companion. His eyes bulged and gaunt face drooped. Holmes turned away from me for a moment, contemplating, his skin turning a sickly ashen hue.

I let a silent moment pass, then I quietly said, “I have upset you.”

He kept his lips closed, his eyes not quite in the present, then the glow returned to his silver orbs, and he stated soberly, “You caught me unawares. I did not expect to ever hear the name of my old instructor again. I consider my work for the man one of the greatest failures of my entire life.”

“Failures!” I stammered. “Why Holmes, the man raved about you. Said you saved his marriage.”

At these words, Holmes mouth turned downward into a deep frown. “Pray tell, what exactly did Mr. Cooper tell you?”

I recounted my patient’s story to Holmes in every detail, though there were not many details to share. Still, as I told Holmes Cooper’s deep praise for the detective, my friend kept scoffing and slowly shaking his head.

“Well, Holmes,” I concluded, “if I may be so bold as to say that even I can deduce your version of events is quite different from that of Mr. Cooper. What happened while you were one of Mr. Cooper’s pupils? And how did you, at such a young age, save the man’s marriage?”

“That, Watson,” Holmes said, bluntly cutting me off and raising his long right pointer finger in my face, “is a rather unique way of explaining the events.” Holmes paused, settled into his chair, and finished off his brandy. He let out a long sigh, and I could tell this was not a story he wished to relate; yet my good friend did continue. “I will tell you the exact details of my time with Mr. Cooper, Watson, with none of my former instructor’s biases; however, I believe you will find this story not fit for the general public. Even with your romanticizing of events, there is not much of a tale to flesh out for your readership. But perhaps, it is a tale worth telling, but first—”

Holmes took a moment to refill our brandy glasses and get his clay pipe and tobacco. He handed me my glass, for which I thanked him, lit his pipe, took a few puffs, and allowed the plumes of smoke to waft in the air before settling into his velvet lined chair and beginning his tale.

“At the age of eleven, I began attending a day school in Kennington. My father had come to the conclusion that his son should be properly educated, not just learning letters and arithmetic from Mother, but a true, formal education. We relocated to a villa in the London suburb, and I attended classes.

“I was a first year and found my school aesthetically displeasing. The rooms were particularly dank and drab. We had no athletic fields, just a small square of asphalt surrounded by towering brick buildings, all as equally run down as the building which contained my classes.”

“But why did your father send you to a school in such squalid conditions?” I inquired.

“Because, my dear Watson, like myself, my father knew quality over prestige. The school had an excellent faculty, even though they had to teach in less-than-becoming circumstances. The Chemistry teacher was particularly noted, as was the instructor in Mathematics. Mr. Cooper was my instructor in Letters, a rather large blowhard who thought more of his capabilities than his abilities warranted.

“Of course in this environment, despite its lack of amenities, I flourished. It was my first taste of formal schooling, Watson, and I thrived.”

“I am sure you were an apt student, the type all instructors dream of having in their classes,” I said.

Here Holmes began to chuckle, but his laughter choked on some of his drifting pipe smoke. After a few good hacks, Holmes caught himself and explained, “My word, no, no, no, nothing could be further from the truth. Often those in positions of authority do not like having their ideas and certainly their position challenged, and as you are aware, Watson, I have no issue letting anyone, no matter their stature in life, know of their inefficiencies. When I would explain to one of my instructors an error that he made, no matter how miniscule, I was met with scorn and derision. For who was I, a mere first year, to question their scholarly integrity? I was surprised by this reaction, for my parents always encouraged my questioning and were quick to admit to their mistakes. This was the first time I was exposed to those who wore their title on their sleeve and felt that the best students kept their tongues stilled.

“A similar reaction came from my fellow classmates. This may surprise you, Watson, but at the age of eleven, I had a sharp mind, yet I lacked my current social skills.”

Here, I bit my tongue and tried not to burst out into loud guffaws. Holmes had many things, a brilliant mind, an encyclopedic knowledge of London, and a strong sense of justice. His social skills, though, were still definitely lacking. Holmes either did not notice my contained outburst or chose to ignore me as he continued on with his story.

“I did not understand the rules of the school yard, nor how to navigate the difficulties of making and maintaining friends. I was not afraid to correct either the teachers or my fellow students, and I was quickly shunned by most of the other boys. Trying to help out a student who was making the most rudimentary errors on translating a passage in Latin was met with fisticuffs on the gravel schoolyard. I swiftly learned to keep to myself, stay quiet, and take in as much knowledge as I could without being noticed by the students or faculty.”

“It must have been a rather lonely time in your life,” I imagined.

“Ah, it actually was not. There were two dear friends which I made during my first year of schooling. One was Mr. Sherman who, as you know is the keeper of Toby, the finest canine tracker whose paws have ever walked the streets of London. I had heard Mr. Lemming, my science instructor, talk of a wonderful shop in Lower Lambeth, in Pinchin Lane, whose owner was an extraordinary naturalist and bird stuffer. One day, I made my way to his shop, and though he was just as suspicious of outsiders then as he is now, I spoke to him of the belief that the ancestors of fowl were prehistoric lizards, and this piqued his curiosity. He let my knowledgeable boyhood self into his rooms, and we began a friendship which, as you know, continues to this day.

“The other friend was a lad by the name of Percival Stevenson, a scrawny, sickly boy who, like me, found himself shunned by the other pupils. He was not a particularly bright boy, though he did have some artistic talent, particularly with watercolors. When I assisted Percival on his assignments, he enjoyed the attention. Indeed, he may not have passed his classes without my assistance.

“Due to Percival’s artistic capabilities, the headmaster had taken an interest in him, as had his daughter, a capable artist who often came to the school to visit her father. It is with the headmaster’s daughter where Mr. Cooper’s case begins.

“Over the course of the school year, Mr. Cooper became enamored with Miss Davis. She was a rather petite and attractive lady in her early thirties, much in contrast to her gnarled and balding father. Miss Davis was a frequent visitor to the school, and she and Cooper were often seen walking the halls together on Mr. Cooper’s off-hours. Had it not been for the fact that Miss Davis was also visiting her father, who clearly approved of their friendship, gossip would have spread throughout the school and into the homes of my classmates. Since it was believed nothing illicit was occurring at the school, for Headmaster Davis would surely put an end to any rumors that cast a shadow upon himself or his school, the romance was allowed to develop in plain sight.

“You may recall, Watson, that in the winter of that year, I became gravely ill with a lingering case of pneumonia. I was frequently absent from my classes, and if it wasn’t for my intellect, would have surely failed. The few times I was able to attend classes, Percival explained what I had missed, and I gleaned the material I skipped during my stays at home. Unexpectedly, over the course of the winter months, Percy blossomed into a striking lad. As I became sick, he seemed to become stronger. His personality changed as his body filled out, and he became more participatory in class and more brazen in his approach towards others. Percy still remained an outcast among our peers, mainly due to a development of condescension towards others he deemed less mentally capable than himself. Yet, despite the changes in the boy as is so common of one of that age, our friendship did not sever; in fact, due to my own intellectual superiority, the bonds tightened, and we became stronger. Percy would derisively discuss the other classmates, how he couldn’t believe their common errors—errors, I reminded him, which he so easily made himself at the beginning of the school year. He also confided in me about his life at home, girls who lived in his neighborhood who had caught his eye and he theirs, and aspirations he had for his future.

‘“Just think, Sherlock, would it not be exciting to be a constable of the law? Arresting criminals and bringing them to justice? I bet that would impress Marcy Wilson!’

‘“Who?’ I inquired.

‘“Why, Marcy Wilson. She lives in my neighborhood and is a true diamond in the rough.’

‘“Ah, yes,’ I said coyly to my friend and then let out a few good hacks from my still lingering cough. ‘With all the girls you are smitten with, it is difficult for me to keep track. Wasn’t it Julia Moreau last week? And . . . let’s see . . . Eva Walker the week prior to that?’

“Percy let out a hearty laugh. ‘They were mere flirtations compared to Marcy, a true Helen of Troy.’

“He sounds like a good man to me,” I said, interrupting Holmes, and noting how much young Percival sounded like a young John Watson.

“Yes, Watson, he definitely had your eye when it came to the fairer sex. But as I said, he was not popular with the lads in the classroom. While I was away much of that winter, Percy became outspoken in the classroom, and unlike me, he knew how to follow the social norms with the teachers, though as far as other students were concerned, Percy was willful and, as I explained, would criticize not only their mistakes but their mental facilities. This caused him to raise the ire of one boy in particular, Willie Muggins, a pig-nosed bulldog of a lad much more suited to the fields of a battle than the seat of a classroom. Muggins struggled in all of his classes, but mostly in Literature, where he could never read below the surface of a story. Percy would ridicule Willie in the classroom, and at first, Willie responded with blows on the schoolyard.

“One early spring day when I was absent, the headmaster caught Willie attacking Percival. Headmaster Davis stormed over to the two boys, holding up his form to its tallest height. Willie was too busy jabbing his fists at Percy who, as I understand it, was doing a sufficient job blocking the blows and getting in a few good punches of his own. At one point, while Willie had his fist pulled back and was ready to take a good lunge in at Percy, Headmaster Davis, who was now directly behind the boy, swiftly reached over and with a strong yank, grabbed Willie by his left ear and twisted. Willie howled in pain as the headmaster kept the ear firmly in his grip and hauled Willie out to the center of the schoolyard. He threw the lad to the ground in front of all the students and then paddled him mercilessly. After Headmaster Davis had sufficiently beaten the boy in public, he ended with an announcement that if a student lay a finger on another student in the schoolyard, they would immediately be met with an expulsion.

“A week after this incident, I returned to classes, still rather weak but definitely on the mend. One morning in Literature class, we were discussing the Morte d’ Arthur. Mr. Cooper was leading a discussion on the ‘Tale of the Sankgreal’, and he had asked Willie why, on several occasions in the story, Galahad boards a rudderless boat.

“‘Why would Galahad board a boat with no captain?’ Cooper boomed. ‘Come now Master Muggins, surely even you can find meaning between the lines of text and answer this rather elementary question.’

“Willie just sat in his seat, red faced and fuming. But the lad did try to answer the question. ‘Because he was brave,’ he tried.

“‘There is nothing brave about sailing off in a ship you can’t steer,’ scolded Cooper. ‘That’s the surest way to commit suicide. Come on, you can do better than that,’ Cooper encouraged. ‘You do like this story, don’t you lad?’

“‘Yes, sir,’ confirmed Willie.

“‘Do you really understand it, though?’ inquired Mr. Cooper as he spoke slowly to Willie, making sure the boy heard the question.

“‘I’m not sure, sir. I’m trying my best.’

“‘You’re trying your best, aye. Come now, think. They are searching for the Holy Grail. Now think my boy, if they are searching for the Grail, why would Galahad board a rudderless boat?’

“Willie scowled at the question. He hemmed and hawed a bit and was probably going to say some off-the-mark response when Percival blurted, ‘Isn’t it obvious! He’s boarding a rudderless boat because it is steered by the divine hand of God.’

“‘Why, yes, excellent answer Master Stevenson. The implication is in fact that God is the captain of the ship.’

“The discussion moved on, but I caught the look of pure spite that crossed the visage of Willie Muggins as he glowered at both Cooper and Percival.

“My next class for that day was Science where, if I recall, we were beginning to study the differences between alkalines and acids. You can imagine how dreadfully bored I was in that class, Watson. As Mr. Lemming lengthily explained something which should have been stated in a mere matter of seconds, I was overtaken with a coughing fit. I asked permission to leave to go to the latrine and recompose myself.

“‘Really, Master Holmes,’ scoffed Lemming, ‘if you are not well enough to attend my class then you should not be at this school. But, I’d rather you were sick outside of the confines of my classroom. Away with you, boy, and when you return, I expect you to take down any notes you missed.’ And with a dismissive wave of his hand, he sent me out of the room.

“To get to the privy, I had to walk down a long corridor containing the Headmaster and teachers’ offices. I walked at a rather slow pace, still feeling weak from my sickness, and I was thinking about how Lemming should be the one sitting in the classroom and I standing at the lectern, when I approached the entryway to the headmaster’s room. The door to his office was ajar, and I heard shouting from within. I instantly recognized the voices as that of Headmaster Davis and Mr. Cooper.

“‘Why would I do such a thing?’ harrumphed Davis. ‘I have already given you my blessing.’

“‘Bah!’ scowled Cooper. ‘Why should I believe you? It would be just like you, Davis, to offer your blessing and then sneak behind my back. You’ve never liked me, which is why I have never been offered the position of Department Chair.’

“‘Ridiculous,’ scoffed Davis. ‘I don’t care a bit if the ring is missing. You still have my blessing to marry my daughter. And as for department head, you have time on your side, my friend. Patience is all you need. Now, wait . . . who’s there?’

“I had burst out into another coughing fit while standing outside the office. When the door flung wide, I had recomposed myself.

“‘Why, Master Holmes? What are you doing here?’ the headmaster asked, and then his eyes became slits and his teeth clenched. ‘Were you spying on us?’

“I explained to the headmaster that I was going to the privy because I was feeling ill. I was overtaken by a coughing fit and leaned against the wall. When pressed if I heard any of their conversation, I looked puzzled and asked, ‘What conversation?’

“The headmaster was satisfied with my answer and Cooper offered to escort me to ensure that I returned to class safely. Afterwards, I returned with Cooper, but on the way to class, he stopped me and brought me into his office.

“‘I’m no fool, Master Holmes, and neither are you,’ he stated gruffly.

“‘What do you mean, sir?’ I asked innocently.

“‘Don’t play games with me, boy. You’re the smartest of the lot and a fine actor. If I didn’t know you better, I’d have been just as fooled as that imbecile, Davis. But the man is right, as I’m sure you noted. He did not take the ring from my coat pocket.’

“‘What ring, sir?’

“‘Come now, Master Holmes, surely you can puzzle it out.’

“I nodded as the answer was obvious. ‘It is the engagement ring you wish to use to propose to Miss Davis, sir. You kept it in the right breast pocket of your coat. Am I right, sir?’

“‘How did you know that?’ questioned Cooper, who suddenly looked at me with a suspicious eye.

“‘Simple, sir. All through class this morning, you kept inserting your hand into your right breast pocket and fidgeting with an object. It is clear to me that it was an item of great importance, as you kept checking to ensure it was still there.’

“Cooper let out a joyful laugh. ‘Indeed you are correct, my dear Master Holmes, and this morning I showed the ring to Headmaster Davis and asked his blessing to propose to his daughter, which he heartily granted. During your class, I kept checking up on the ring, mulling over my word choice for when I proposed to the fair Miss Davis. But after your class, I noted that the ring had gone missing.’

“‘And you believe it was a student who took your ring, sir.’

“‘Yes, Master Holmes, and I believe you are the man who can get me my ring back.’

“‘Me, sir?’ I questioned, truly surprised at the turn in this conversation.

“‘Yes, Master Holmes. You are the cleverest man in this school, and that includes both teachers and pupils, and I don’t mind saying so. I need your help, boy. Can you return the ring to my possession by the end of the school day?’

“‘How would I do that, sir?’

“‘Why, Master Holmes, I have given you a challenge, a fitting challenge for your intellect. I would betray you if I gave you any ideas about how to solve this mystery.’

“‘May I ask a few questions, sir?’

“‘Be my guest, Master Holmes.’

“‘When was the last time you remember having the ring in your possession?’

“‘Well, let’s see, it was before the end of class. Then, after you were dismissed, I spoke to Master Muggins about his efforts, then I noticed the ring was missing. Why, you don’t suppose . . . ?’

“‘I don’t suppose anything, sir,’ I answered, ‘but I do believe you will have the ring in your possession by the end of the day.’

“And with that, Watson, I left Cooper’s office, excited for this opportunity to prove myself, for it was a true opportunity. For the first time since I entered that school, I felt that an instructor took a wholehearted interest in me, saw me as an intellectual equal, superior even, and was challenging me. It was my duty to rise to the occasion.”

I was taken aback by the turns in Holmes’s narrative. How could a grown man turn to a mere child, even one of Holmes’s intellect, to solve such a personal matter? My friend, who had paused to take a few puffs from his pipe, read the expression upon my face and answered my unstated question.

“Watson, I can see that you disapprove of Cooper asking a pupil to solve his personal dilemma. The man should not be faulted; he should be recognized. I still find it one of his more positive attributes that he was able to note my intellectual prowess and not let age or position in life interfere with the most logical person to solve the case of his missing ring.”

“And you solved the case, Holmes?” I inquired.

“Of course, Watson. Today, I would dismiss such a case as not being intellectually stimulating; however, at the age of twelve—yes Watson, twelve, my birthday was that January—I found the case to be somewhat of a thrill.”

“A thrill, Holmes! Really!” I stated bluntly, for it was obvious to me that Willie Muggins was at fault. The lad had sought revenge for his embarrassment by Cooper in his classroom.

Holmes nodded silently. “A case, even one as simple as this, held my attention. I knew who was at fault, yet I still had the problem of actually retrieving the ring. Where would the ring be hidden? The answer, of course, was obvious. The best hiding spot for the ring would be in a coat pocket, such as it was the best place for Cooper to conceal the ring. Fortunately, it was a particularly warm afternoon, and when we were released for time in the courtyard, all of us removed our coats and stored them on the coat rack in the hallway before disappearing outside and enjoying the balmy spring day.

“With all the first years away from the coats which were hanging in our designated rack inside, I knew I had the perfect opportunity to retrieve the ring.

“I sought the aid of my dear friend Percy in executing my plan for the ring’s retrieval. Percy listened intently to my story, and when I finished explaining, he stiffened up and said, ‘I am at your service, Sherlock.’

“The plan was simple. Mr. Henderson, the burly History teacher, was outside, keeping an eye on the students, making sure that no fights broke out in the yard, especially after the headmaster’s thrashing of Willie and his threat to the students. As Percy and I were walking by the man, I started another of my coughing fits and actually fell on the ground in front of the instructor. After a few harsh hacks, Percy helped me to my feet, and I asked if Percy could take me inside to get a glass of water. The teacher agreed to my request.

“Once inside the school, I went to the coat rack, found Willie’s jacket, and when I returned to the schoolyard, I had Cooper’s ring safely in my possession.”

“Well done, Holmes,” I commended my friend. “Even at such a young age, you were extraordinary at puzzling out a dilemma.”

But at this congratulations, my friend’s lips turned into a deep slit of a frown and his skin took on a grey pallor. “I puzzled out this simple problem, but I still ended up making what I fear was one of the gravest errors of my life.”

“I don’t understand, Holmes,” I said, completely perplexed. He kept referring to the case as a failure, and yet it was a rather straightforward success. In fact, I found the case so routine as to be too dull to share with my readers.

Holmes leaned back in his chair, his fingers steepled and eyes stared off to the memory of his youth. He spoke softly with a touch of melancholia in his voice which I had only heard on a rare occasion. “At the end of the day, I reported to Cooper’s office. I could see the greedy anticipation in his eyes as he sat in his chair fidgeting, his fingers tapping each other in such a way as to appear that they were fighting amongst themselves. When his emerald eyes fell on me, I gave him a boastful smile, and he knew I had completed my mission.

“‘You’ve done it Holmes! You have the ring!’ exploded the ruddy-faced man.

“I shrugged my shoulders and held out my left fist, palm up. I uncurled my fingers and there, resting in the center of my hand was Cooper’s ring.

“As quick as a hawk pouncing on a mouse, the man snatched the ring from me and held it up towards the lamplight, inspecting it to make sure it was not damaged.

“‘Good show, lad!’ he said through jolly chuckles. ‘Good show. You were able to get it away from Muggins. I’d love to see the look on that boy’s face when he realizes he doesn’t have the ring anymore. I will get to see his expression when he sees my dear Miss Davis with the ring upon her finger. It will be perfect. But tell me something, Master Holmes. In the afternoon, just an hour ago, I came up with an excuse and had Master Muggins called to my office. I had him turn out his pockets, and the boy had nothing but a dull pencil. I thought he would know why I sent for him, but the lad was a fine actor, pretended he knew nothing about any missing ring.’

“‘That’s because,’ I bragged, ‘’twas not Muggins who took your ring, sir. You had it all wrong, sir.’

“Cooper’s face plummeted at this news. His eyes bulged, and he looked as though I had struck him across the cheek. ‘Not Muggins,’ he stammered. Then, he burst out into one of his hearty laughs. ‘You are one of a kind, Master Holmes. One of a kind. So, indulge me, my boy. Who, pray tell, took the ring from my pocket?’

“‘The answer is quite simple, sir. ’Twas Percival Stevenson who snatched your ring.’

“Percival!” I admit, just as Mr. Cooper must have done, I sputtered at this declaration. I thought Holmes would chastise me for being surprised that his childhood friend was a common thief. But he did not comment nor even acknowledge my reaction. He kept telling his tale in that same, somber tone of voice.

“I explained everything to Cooper, Watson. I told of how I saw Percy palm the ring from Cooper’s pocket when he was distracted at the end of class and chastising Muggins. I said how I had told Percy when we were in the schoolyard that we could get revenge on Muggins by sneaking inside and stealing several sovereigns I said he had in his coat pocket. Of course, that was a complete ruse. When I had my fake coughing fit on the schoolyard and Percy helped me inside, I was able to snatch the ring from his pants pocket where he kept it, and replaced it with a stone I discovered of about the same size and shape. When we went to the coat rack, I used my own money which I had in my pocket, and I showed it to Percy after we returned outdoors. He assumed that I had stolen the money from Muggins when I had it in my possession all the time.”

“Astonishing Holmes,” I said, impressed with his youthful skills. Then, I inquired, “But I do not understand why your friend would take the ring? Had his family fallen on hard times? Did he have a vendetta against Cooper, or was it just a bit of a lark?”

Holmes lowered his eyes and shook his head. “Your questions are almost identical to those asked by Cooper, and I was such a braggart, so proud of myself, that I told Cooper everything without thinking of the consequences.

“‘It all has to do with Miss Davis, sir. I’m surprised you haven’t seen it yourself,’ I stated to Mr. Cooper.

“Here Cooper eyed me most suspiciously. ‘Seen . . . what . . . ?’ he inquired with a drawn out drawl, as if he was not sure if the answer should be obvious, if he wanted to hear it, or if he should even trust me.

“‘As you like to say, sir, the answer is rather elementary. I’ve noticed when Miss Davis is with Master Stevenson how much alike their visages are. I’ve also noted that both walk with a slightly odd gait, one where the right foot turns out and the toes curl at each step. With the interest which Miss Davis shows towards Master Stevenson and their physical similarities, I quickly deduced that Miss Davis—’

“‘Is Master Stevenson’s mother,’ concluded Mr. Cooper. His face had turned sickly and his lower lip quivered at this information.

“‘That’s right, sir. I believe Percy stole your ring so that you would not be able to marry his mother. I do believe he likes you. He’s just being protective of his mum.’

“The man composed himself enough to thank me for this news, and he sent me on my way. Fool that I was.”

“Why, Holmes, you are being far too harsh towards yourself. I believe you did Mr. Cooper a good turn,” I said reassuringly.

“A good turn,” Holmes spat. “And what do you think happened after I told Cooper all that I had learned?”

“Why, of course the gentleman did not marry Miss Davis,” I stated matter-of-factly. “I assume that the child was illegitimate, since Miss Davis was never presented as a widow, and therefore, that Miss Davis was not a suitable choice for Mr. Cooper. Also, I hope the boy was harshly punished for his crime.”

“Not a suitable choice,” Holmes said sadly with a slow shake of his head. “You hope the boy was harshly punished! Oh Watson, you are a traditionalist to the point where you don’t see the harm it can do.”

“Really, Holmes. I don’t see—”

“No, you don’t,” Holmes snapped, and I could tell that I had raised the ire of my dear friend. “Rest assured that young Percy did get punished, but it is my belief it was unwarranted. Indeed, the guilt that I feel—” Holmes caught himself. He was shaking slightly, feeling a mix of sadness and rage. Finally, he took a swig of brandy, let out a long sigh, and recomposed, continued in his soft, melancholy tone of voice. “Had I just returned the ring to Cooper and not revealed where I had gotten it, he would have been none the wiser, would have married Miss Davis, and I’m sure, in good time, would have learned the truth, and instead of turning away, he would have adopted Master Stevenson, whom he would have grown to love. Percival would have found himself in a joyful family situation.

“Instead, Mr. Cooper did not only reject Miss Davis. He also, after sending me away that afternoon, went straight to the headmaster and threatened to expose the secret of his illegitimate grandson unless he made Cooper the department chair.”

“My goodness, Holmes. Did he really?”

“He was furious, Watson. He thought the headmaster was trying to trick him into marrying Miss Davis. Percival never returned to school. I never saw my friend again.

“You see, Watson, one of the tricks of being a true detective is that one must solve a case, but one must know how much information is proper to reveal in doing so. I was right to take the case, but I was wrong to identify the guilty party. It is why, as you’ve noted, sometimes my tactics are quite different than those of Scotland Yard. I wish I could wind the clock back, knowing what I know now and put that knowledge into the young version of myself. I solved the case, Watson. I suppose it was my first true case, yet in the end, I failed my friend, and that is unforgivable.”

“You were just a boy,” I started.

Holmes dismissed me with a wave of his lanky arm. He did not want to hear my excuses for his conduct.

“Now, Watson, the hour is getting late, and you should return to your home, to your wife. If you’ll excuse me, there is a ‘Concerto in D Major’ which I would like to practice. It is a rather fitting piece on this somber afternoon.”

As I limped down the steps that late afternoon, I heard the piercing wail of the detective’s violin while he began to play his lament for his childhood friend. Those haunting notes stayed with me all through my cab drive home and into my dinner with my wife, Mary. I found myself feeling a sense of guilt and despair, for while my friend mentioned his failure to young Percival, I realized that in many ways I had failed Holmes as well. In my two published recounts of his adventures, I had presented the man as a cold, calculating machine. Nothing could be further from the truth. Holmes had a strong sense of justice and fairness. He preferred to help the downtrodden than the elite, and he would let a crook go free if he knew the criminal would right his wrongs and never commit a crime again. It was better to do that than send a man to jail where he would harden and seek a life of lawlessness. That appreciation for the human condition was lacking in my characterization of Holmes, and this was a wrong that I had to right.

I had been toying with an idea of focusing on shorter narratives and writing a series about the greatest adventures which I had shared with my friend. But where would I start? There were so many tales to choose from. Perhaps I would start with a case where Holmes was not triumphant. Perhaps a narrative where Holmes shows disdain towards the aristocracy, maybe even royalty, displaying a sense of respect towards someone like a child, or a woman. That was it! A woman! The Woman! I thought of the portrait on Holmes’s mantel, put pen to paper, and began to write.