The Adventure of the Paradol Chamber

By Paul W. Nash

This story first appeared in the MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories Volume XIII.

Paul W. Nash grew up in the shadow of the Bodleian Library at Oxford, where he worked as a junior library assistant between 1981 and 1994 and as a senior library assistant from 2007. He makes his living as a bibliographer, cataloguer, editor, book-designer and printing historian, pursuing the mysteries of bibliography very much as Sherlock Holmes might have done, had he been a librarian. He is fascinated by the traditional processes of printing and has his own private press at which he prints small works of fiction, poetry and humour. Writing stories and musical composition have been hobbies throughout his adult life and he is now officially a doctor, albeit not in a useful sense (like Dr Watson), holding as he does a doctorate in Publishing History from Oxford Brookes University.

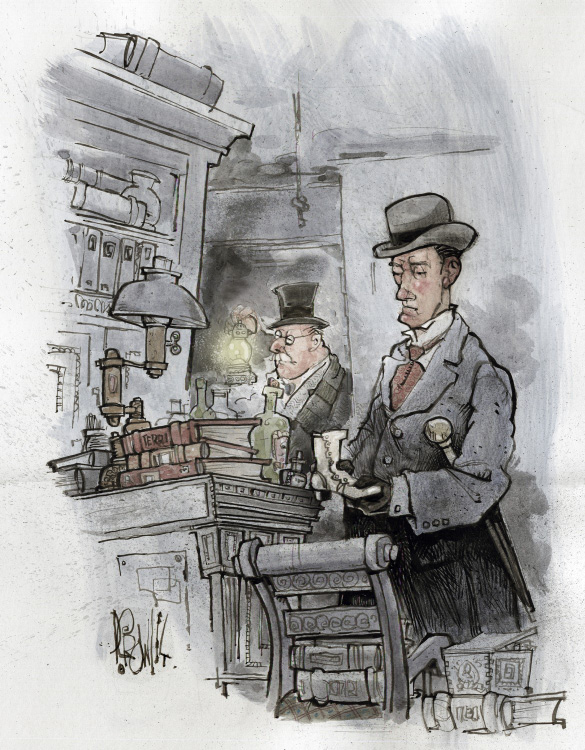

Pat Crowley was the Editorial Cartoonist and Creative Director for the Palm Beach Post (Florida) from 1978 to 2008. He was a founding staff member and first political cartoonist for The Hill newspaper in Washington D.C. (1994–99) and contributing artist to the New York Times. His political cartoons were distributed to hundreds of newspaper and periodicals throughout the United States by the San Diego based Copley News Service.

Artwork size: 11” × 12.5”

Medium: India ink and water color paint

The year 1887 was a busy one for Sherlock Holmes. He was engaged in a dozen cases of note, including the adventures of the Five Orange Pips and of the defeat of Baron Maupertuis, the Hoxton Devil, and the Amateur Mendicant Society, not to mention the very curious case of the Hollow Effigy, all of which are recorded in my notes (though some cannot be made public until the noble and gentle personalities involved have been forgotten). Perhaps the strangest case of the year, however, was that of “The Paradol Chamber”. It represented a triumph for Holmes’s powers of ratiocination, and marked for me the end of an old phase of life and the beginning of a new.

It began one balmy afternoon in July. Holmes was still in delicate health after his prolonged battle of wits (and fists) with the Baron, but he was in good spirits again after the black reaction to his herculean efforts of the spring, cheered by his successes and the recent Jubilee. We were both lounging in the rooms in Baker Street, Holmes toying with one of his musical compositions, humming short snatches to himself as he scratched with his pen, while I was absorbed in the latest outrageous tale in Blackwood’s. Suddenly Holmes threw aside his manuscript and jumped to his feet.

“I had quite forgotten,” he cried. “We are to receive a visitor this afternoon.” He plucked a letter from the mantelpiece and threw it into my lap. I picked it up and read as follows:

Dear Mr. Holmes,

I am sure you will not mind if I call upon you this afternoon at four o’clock to discuss a little matter which has troubled me. My name will, I am sure, be known to you, but I do not seek any favour on account of my fame. Please treat me as you would any common client.

Yours most sincerely,

Beresford Lamb

“I received it this morning,” said Holmes. “What do you make of it?”

Knowing my friend’s methods, I addressed myself first to the physical characteristics of the letter. “Well,” I replied, “it is written on very good-quality paper, with a broad-nibbed pen, in a round, confident hand. The writer has not commissioned a printed heading for his letter-paper, but has attached a copy of his calling card to the top of the sheet with a pin. The card gives an address in Endell Street and is somewhat pretentious in execution, with rather too many curlicues. I suppose Beresford Lamb must be well-to-do as well as being, as he remarks, quite famous.”

“Is he famous?” asked Holmes. “I confess I had never heard of him before I read his name here.”

“He is certainly known to me.”

“Really? Is he, perhaps, a celebrated jockey or tipster upon the turf?”

“No indeed,” I replied gravely, feeling that Holmes was chaffing me rather. “He is an author.”

“An author? Of what cast?”

“He writes dramatic stories of crime.”

“Not reports of crime? Surely, I should have heard of him had he been a recorder of criminal proceedings.”

“No. His work is pure fiction. But I am surprised, nevertheless, that you have not heard his name. He has become well-known from these very pages.” I raised the copy of Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine that I had been reading.

“I see,” said Holmes. “Have you read all his works?”

“Hungrily,” I replied. Lamb was among the more successful of a group of writers who had taken to inventing bloody and unlikely tales of crime and detection in the past decade or so. I remembered with pleasure Mr. Collins’s Who Killed Zebedee and Miss Green’s The Leavenworth Case, and almost as fondly the serialisations of Dr. Casterman’s cases in The Cornhill and those of “Lupus” in Once a Week. My black bag contained, at that moment, an unopened copy of The Mystery of a Hansom Cab, of which I had heard very good reports.

“Well,” said Holmes. “We have a few minutes before our visitor is due. Perhaps you would tell me a little of Mr. Lamb’s works.”

“I have just finished reading the final part of his latest story,” I replied, “and will be delighted to give you an account of it. It is a tale of love and attempted abduction called “The Adventure of the Paradol Chamber”, and is the latest in a series of The Chronicles of Lord Pinto. This Pinto, the Viscount son of the Earl of Fullerton, is an amateur detective.”

Holmes held up his hand. “A detective?” he said. “Like myself, rather than of the official variety?”

“Not quite. Pinto is a rich man who pursues detection as a hobby, while you are England’s foremost professional consulting investigator.”

I felt a little flattery would do no harm to my friend, or my narrative, at this moment. Holmes smiled with a mixture of pleasure and condescension. “Pray continue, Doctor,” he said.

“Although Pinto is a noble amateur, I have noticed, once or twice when reading of his exploits, that there are echoes of your own work and methods. Accounts of your successes have been available in the public prints, and I am sure Lamb has taken a little inspiration from you.” Holmes continued to smile.

“The story concerns a stage magician who calls himself ‘Paradol’. He works with a young assistant on various astonishing illusions, and soon forms a powerful regard for the beautiful daughter of the owner of one of the theatres in which he performs. He pays court to this girl, but she spurns him and, in the way of such stories, her rejection turns his genius from light to dark, and he plots his revenge. The climax of his act is the appearance of The Paradol Chamber. This is a gaudily-painted vanishing-box, six feet tall and three feet wide, with a door on the front, which the assistant brings on to the stage. It is raised to a height of about a foot on four wheels, which allow it to move easily and the audience to see beneath it while the trick is performed.

“Paradol would invite a beautiful woman from the audience to join him on stage, and ask her to step into the Chamber. The door was then closed and the assistant would turn the Chamber round upon its wheels through three-hundred-sixty degrees to allow the audience to see the back and sides. All the while, Paradol would make exaggerated signs and passes as if conjuring powerful magic. He would then open the door of the Chamber to reveal that it was now quite empty. The audience would inevitably gasp. Then Paradol would bow and step into the Chamber himself and close the door. The assistant would repeat the revolution of the Chamber and this time when the door was opened the beautiful lady was standing again inside the box and Paradol had disappeared. This was the end of the act and, while the lady left the stage and the audience clapped loudly, the Chamber was wheeled into the wings.

“We are told how the trick was done. It was a very simple matter. The interior of the Paradol Chamber was covered with black velvet and was divided vertically into two compartments by a velvet-covered board which revolved on a central pivot. When the door was opened, only the front half of the Chamber was actually visible, but this was not obvious because of the blackness of the interior. The lady chosen from the audience was, of course, a confederate of Paradol, and once inside the Chamber knew how to revolve the central board and pass into the back compartment. When the door was opened, the audience could again see only the empty black interior of the front half of the box. Clearly, when Paradol himself entered the front compartment, the whole process was reversed and the two compartments changed places.

“So much for the trick as it was usually effected. But on one night Paradol practised a dramatic and potentially fatal variation.” Holmes snorted. Perhaps I had grown a little caught up in the narrative and decided to continue it without embellishment. “He paid his usual lady accomplice to feign illness, and suggested to the theatre-owner that his daughter might take her place. To this he readily agreed, and the daughter was initiated into the secret of the trick. At the climax of the act she was picked out, seemingly at random, by Paradol and entered the Chamber. While the magician’s assistant turned the box to show its faces to the audience, the young lady revolved the central board and entered the hidden compartment.

“But the ingenious Paradol had prepared the Chamber differently that day. He had drilled a number of holes in the floor of the hidden half of the Chamber, and beneath them fastened a shallow metal box stuffed with cotton-wool soaked with chloroform. The girl naturally fell into a deep sleep. Rather than enter the Chamber himself, Paradol then bowed to the audience, received their plaudits, and left the stage, while his assistant wheeled the Chamber after him. Usually the Chamber would be halted and opened as soon as it was in the wings, but now Paradol took charge of it and, with his assistant’s help, wheeled it to the stage door, which he opened. Then he departed through it, quickly to return driving a small cart and pair. The Chamber was loaded into the cart and the magician drove off into the night with his sleeping prize.”

“The next part of the story is a curious dream or vision which Paradol enjoys as he drives away, thinking of his new life with the young woman he has abducted. He fancies he will open the Chamber and take out her sleeping form and lay her on the bed in the cottage he has rented, to recover from the effects of the chloroform. When her head is clear, she will perceive her situation and give herself willingly to her abductor in marriage. Paradol will revert to his own name, which no one in the theatre world knows, and a priest will be called to conduct the service. Then he will choose a new stage-name and continue his career. But when he arrives at the cottage and opens the Chamber he finds it quite empty.

“In the third part of the story, Lord Pinto makes his appearance, called in by the theatre-owner to trace his missing daughter. The official police have, naturally, failed to solve the mystery and have suggested that the disappearance was merely a carefully planned elopement. Pinto begins his investigation and learns that the magician’s young assistant has also disappeared. After much circumlocution, and not a few co-incidental discoveries, Pinto traces the assistant to a rented room where he is living with his new wife, the theatre-owner’s daughter. It transpires that the assistant too had been in love with the girl and, perceiving at the last moment what Paradol was about, had rescued her from the Chamber while his master was fetching the cart and replaced her sleeping form with a couple of sandbags which were used in the theatre to secure scenery. Upon waking, she had recognized her rescuer, declared her love, and willingly run away with him, believing that her father would no more welcome as a son-in-law a young stage assistant than he would a mature stage magician.

“The story then turns to the pursuit of Paradol. Pinto gains from the assistant certain clues which allow him to locate the magician’s cottage. He alerts the local police who meet him at the cottage, where they confront Paradol—and Pinto recounts, to the magician’s astonishment, the full story of his abduction of the girl. When he has finished, however, Paradol asks the police inspector what crime he is going to be charged with, since there is no evidence of any of Pinto’s claims and the girl was not, in fact, abducted by him but eloped with his assistant. The inspector scratches his head, but Pinto smiles and leads the party to an outbuilding where they find the Paradol Chamber, newly-painted in a different livery, but still the same machine. He produces a hand-bill for the magic act of one ‘Eggestein the German Wonder’, and opens the Chamber to reveal the unconscious body of another young woman. It is her abduction with which Paradol is charged.

“Upon finding that he had been cheated of the prize for his ingenuity, Paradol’s heart had turned quite to wickedness, and he had determined to use his skills to take possession of the most beautiful young women of the region, repeating his trick in local halls and theatres under a series of different names. At the last, he is led away to prison, and the girl wakes to find herself in safe hands, with no knowledge of the fate which she has so narrowly escaped.” I paused and looked at Holmes, trying to gauge his reaction to the story. His face was quite impassive however, like a severe carving of granite. “I enjoyed the story very much,” I said. “Indeed, I found it . . . thrilling. But, I admit, it is a ridiculous tale, full of melodrama and implausible detail.”

“I disagree,” said Holmes sharply. “It is certainly romantic and melodramatic, even grotesque, but not wholly implausible. I can see only one possible flaw in the logic of the tale as you have related it, and that is the question of the chloroform held in a box beneath the floor of the Chamber. Would such an arrangement have been effective? And would not the odour have alerted the young woman that she was entering a trap? But then, why would she recognize the scent of chloroform?”

I had not expected Holmes to consider the story quite so seriously. “Perhaps,” I said, “you should read ‘The Adventure of the Paradol Chamber’ for yourself.”

“Perhaps I should,” he replied. “But all that must wait, for here, if I am not mistaken, is the creator of that story.” The small clock on the mantel chimed the hour and, in the same instant, there was a ring on the doorbell. After a few moments, we heard the regular footsteps of our visitor, and momently there was a firm rap upon the door.

Holmes paused a moment then called out, “Come in.”

A tall gentlemen in a long brown coat entered. His brown bowler was held in the long, elegant fingers of his left hand, and in his right he held a gold-topped cane. He must have been well over fifty years of age, but his hair was coal-black, and swept back from his face in a sharp peak which he must have smoothed down just before entering our door. His face wore an expression of alert interest, and his blue eyes were especially piercing and earnest. At Holmes’s invitation he handed over his hat and stick, removed his coat, which Holmes also took, and sat down beside the empty fireplace.

“So,” said our guest when he was settled, “you are the famous Sherlock Holmes?”

“I am he,” replied Holmes. “And this is my friend Dr. John Watson, who is has occasionally been good enough to assist me in my cases.”

Lamb nodded to me, then turned back to Holmes. “You will know my name, of course,” he said. “Have you read my stories?”

“I have some familiarity with them.”

“Very good. I have followed your career too, as far as I have been able, through accounts in the daily papers. I must congratulate you on your triumph in the case of the Baron and the British antiquities. I gather you saved the French government something like a million, and the Greek nation a similar sum, and ended by knocking the Baron down the steps of the British Museum when he took exception to your interference . . .”

“The accounts of the Baron’s downfall in the papers were, I fear, a little purple. But I can count the case among my successes. Now, what can I do to assist you, Mr. Lamb?”

“I have received a letter,” he said, “which has troubled me. It came last Friday, and I have been wondering ever since how to understand it. This morning I decided my best course would be to show it to you.” Lamb took a sheet of folded paper from his pocket and handed it over. Holmes read it carefully, then took the sheet to the window and used his glass to examine the paper in the summer sunlight which shone in. Then he handed the sheet to me and, for the second time that afternoon, I found myself reading a letter addressed to another man. This time, however, the text was not a little shocking. It read in this way:

Mr. Lamb

You are a basterd and murderer! You are responsable for my Ellen’s death, as sure as if you had strangled her with your own hands. She would never have left the comfort and safety of her own home and gone off with that man but for you and your wicked story of the Dashing Carman. Be sure, Mr. Lamb, that I will have my revenge, if it takes all my skill and cost my life. Yours is forfit, Sir, for the wickedness you have done.

Your most bitter and determind enemy

Tom Charlett

Having read the text, I studied the physical properties of the letter, attempting to follow the actions I had seen Holmes take. It was written with a sharp-nibbed pen with such force that at times the nib had quite broken through the paper, which was smooth and white, octavo in size. It had been folded twice, clearly for insertion into an envelope, since there was no sign of a seal, address, or stamp upon the back. I held it up to see the watermark and read “Joyn” and “Super”. Holmes would surely have recognized this at once, as I did—as all that remained of “Joynson Superfine”, the mark of one of the commonest writing papers in the Empire.

“Well,” said Lamb at length. “Should I take it seriously? It seems a very bitter threat to me—and yet I cannot believe the writer is quite in earnest . . .”

“Do you still have the envelope?” Holmes asked.

“Regrettably, I threw it away. I remember it was buff and was addressed to me, care of Blackwood’s London office, using the same handwriting.”

“What is this reference to your story of ‘The Dashing Carman’?”

“Have you not read it, Mr. Holmes . . . ?”

“I regret not, but perhaps Dr. Watson?” He glanced in my direction.

“Yes, indeed,” said I. “I remember ‘The Adventure of the Dashing Carman’ very well. It concerned the beautiful daughter of a cruel Banker, who was loved by an ugly Viscount, who was far above her station, and a handsome Carman, who was far below. Lord Pinto was consulted by the Viscount when the young woman disappeared. He discovered that she had secretly married the Carman and was living with him in a humble place. When the Viscount learned this, he attempted to murder the girl, which had been his intention all along, as revenge for her rejection of him, while her father hunted down the Carman with the same end in mind. Pinto saved them both, defeating the Banker—who was ultimately reformed—and the ugly Viscount, who ended by fleeing into the path of a locomotive at Paddington Station. I have noticed, Mr. Lamb, that your stories often involve a beautiful daughter, and an elopement.”

“You are perfectly right,” said Lamb. “My readers like nothing better, and I try to please them. The other factor in my stories is, of course, crime, most usually a murder or abduction, and here too I do my best to satisfy my public.”

“How very admirable,” said Holmes. If he was being sarcastic, Lamb did not detect it.

“You are most kind,” he said. “And Dr. Watson—though he has omitted all the most interesting and original points in my story—has put it into a nutshell and touched upon the vital element—that this tale might be seen as an encouragement to a romantic young woman to defy the wishes of her father and elope with a good man of lowly station.”

“What of the woman, this ‘Ellen’?”

“I know only what can be inferred from the letter,” said Lamb, “that she was among my readers, eloped, and was later murdered.”

“And Tom Charlett?”

“A relative, I presume. Most likely her father. I have never met the man, and yet he blames me for Ellen’s killing. It is perhaps one of the hazards of the occupation of writer, that some deluded person may read a great deal more into your words than was ever there. It is as if Macbeth were to be blamed for a case of regicide, or Mr. Dickens for a cruel gynaecide.”

“Not quite,” said Holmes. “I do not believe either Shakespeare or Dickens could be said to have encouraged murder. Both Macbeth and Sikes suffered for their crimes, while your story, if I understand it, might encourage not homicide, but elopement.”

“You are quite right, Mr. Holmes. But what should I do?”

Holmes took up the letter again and peered at it narrowly. “Since we cannot know, at present, whether this letter is real or its writer’s extremity of feeling continues, we must, I think, treat the threat as very serious indeed. For the time, Mr. Lamb, I would advise you to lock your doors securely and keep a pistol always to hand, to guard yourself most carefully and, if possible, never to venture from your house except in the company of some trusted male friend.”

“Thank you, Mr. Holmes.”

“There is one further course of action I should advise. You should take this letter, and your fears, to the official police. A very serious crime may be in contemplation, and the police would, I am sure, take these threats most seriously.”

“I hesitate to go to the police, for I know what fools they are.”

“I am surprised to hear you say so.”

“As you know, my experience, reflected in my stories, is that there is nothing more slow-witted and slow-moving than the average British policeman. They are inclined, I believe, to see crime everywhere except where it is actually taking place, and to judge by the merest appearances all cases that come before them.”

“There is some truth in what you say,” said Holmes. “But not all policemen are such imbeciles, and a few, a very few, come close to being able in their profession. In any case, the official force can assign a man or two to your protection and can put the entire metropolis on watch for this Tom Charlett.”

“Very well,” said Lamb. “I will do as you ask. But I do not trust the police to get at the truth.”

“I will do my best to find the truth,” said Holmes, “both about the letter, and about the murder. Once the killer is apprehended, Tom Charlett will have a more just focus for his bitterness.”

“Thank you.”

“You will not mind if I keep the letter for a while?” said Holmes.

“Will I not need to show it to the police?” Lamb asked.

“If you tell them of its content, and that I have the original for safe-keeping, the police will take your story seriously enough.”

Lamb rose and bowed to each of us in turn. Holmes put the letter away in his pocket-book then fetched Lamb’s coat, cane, and hat. Without another word, the famous author left our sitting room.

“Well,” said Holmes, “what do you make of our writer and his story?”

“It seems serious to me,” I replied. “If this Charlett blames Lamb, however unjustly, then his life must be in danger.”

“Indeed. That ‘if’ is a most important word. I cannot help but feel that we have had today, from start to finish, nothing but fiction. Yet parts of the story may be, indeed must be true. I did not mention the fact to our client, but I well recall the case of the murder of Ellen Charlett. It was reported early last week. As you know, I make it my business to keep up with the criminal news, and read especially the more sensational literature on the subject, though pure fiction concerning crime I have always considered beyond the pale. I docketed the crime and no doubt have a few notes upon it my index. Perhaps you would reach over to the shelf to your left and draw out the volume for ‘C’? Thank you.”

I passed the heavy, green-bound volume to Holmes who turned through the pages slowly, smiling and muttering to himself. “Camden Theatre Mystery. Castle Graham Imposture. Cats, Seven Black. Cervical Vertibrae . . . Ah, here she is, the Charlett Murder, lying neatly between the Chadlington Horror and my late lamented friend Charlie Peace—a long entry for him, but only a scrap for the unfortunate Ellen Charlett.” He passed the book to me and I found a very brief newspaper clipping from The Daily News of the twenty-seventh of June, 1887, which ran in this way:

The murder, by strangulation, of Miss Ellen Charlett, daughter of Thomas Charlett, master-tanner, of Clerkenwell has been reported this morning. Inspector Lestrade of Scotland Yard told The News that it was a simple case and he expected to announce the arrest of the killer imminently.

“Well,” said Holmes, “that gives a little useful information. Our friend Lestrade is on the case, and we have Mr. Charlett’s address and profession. In the morning I will summon Lestrade and we can begin our investigation. But for now we may perhaps best occupy ourselves with a little reading. I will assay the final episode of Lamb’s “Paradol Chamber” in Blackwood’s. You may perhaps have some similarly uplifting work to occupy your mind.”

I remembered the copy of Hume’s Mystery of a Hansom Cab in my bag and needed no further prompting to draw it out and begin the story.

The next morning, Holmes’s telegram brought Lestrade to our rooms, where he told us what he knew of the Charlett case. It seemed the manager of Willis’s Private Hotel in Highbury had reported the death of a young woman in one of his chambers. Lestrade had been called in to find it a clear case of murder. The girl had been strangled with a bootlace. The hotel register showed that the room had been taken by “Mr. and Mrs. E. Smith”, but of Mr. Smith there was no sign. His clothes and possessions were gone from the room, while the girl’s remained. The body was identified as that of Ellen Charlett, the daughter of Thomas Charlett, who had reported her missing a few days earlier. Charlett believed his daughter had run away with her lover, an unsuccessful actor named Elias Smith, whom he had forbidden his daughter to marry. Lestrade sought a description of Smith, but Charlett had only seen him once, and that from a distance, as he had been afraid to come to the house. The hotel clerk and porter gave similarly unhelpful accounts of his appearance, as he had worn a long coat and scarf, though the night was warm. All Lestrade could gather was that Smith was tallish and of middling build. The inspector enquired around the theatres of the city, but no one had heard of Elias Smith, so that he must either have given Ellen a false account of his profession, or a false name.

“We are still looking,” concluded Lestrade, “but I wish you would give me a hint or two as to how, or where, to look.”

“I believe I can help you best,” said Holmes, “by suggesting that you may never find Elias Smith, at least not alive.”

“What, you mean that he has done away with himself?”

“Not at all. I think it quite possible that he too has been murdered, by the same hand that did for Ellen. I am reminded of a story I heard recently of a Dashing Carman whose beloved was the focus of a rival’s jealousy and a father’s anger.”

“Why, yes. A rival for the girl’s affections . . . or perhaps her father—he had cause to hate Mr. Smith, well enough, and perhaps his own daughter too . . .”

“It is a thousand pities that I was not able to visit that hotel room myself after the body had been found. The killer must have left some marks. I suppose the room has now been cleaned and re-let, and the girl is buried?”

“Yes, indeed.”

“What of her possessions and clothes?”

“She had little enough, but what she had is still in store at Highbury Station. There is a little jewellery, a book, a couple of magazines, some money, and several sets of clothes. You can see it all, all except her shoes. We never found those.”

“That is a curious circumstance, is it not?”

“I thought nothing of it at the time,” said Lestrade, “assuming Smith had taken them with him by mistake, among his own things.”

“Possibly . . . Yes, Lestrade, thank you, I should like to examine the young lady’s clothes and possessions.”

“You can come to the Highbury Station, any time you like, and see them.”

“Perhaps you would be a very good fellow and have them packed up and sent to me here. Thank you. Now, before you leave, I wonder if I might ask one more question? You mentioned that the lady had been strangled with a bootlace. What sort of bootlace?”

“A common brown bootlace,” said Lestrade laconically.

“A leather bootlace?”

He brightened. “Why yes, I see. Thank you, Mr. Holmes. I am sure I would have thought of it in time, but I am most grateful for the hint all the same.”

Lestrade rose and bade us farewell. As soon as he was gone, Holmes said, “I, too, must leave for a short while.”

“Really?” I replied. “I believed you had quite made up your mind to solve this case without leaving your chair, as you have done once or twice before.”

“I would like to get to Mr. Charlett before Lestrade arrests him. Perhaps you would pass me the London Directory? Thank you.”

I handed him the great red book and he opened it near the beginning and turned over a few pages. “As I suspected,” he said. “There is only one T. Charlett listed as a tanner, at No. 5 Ray Street, Clerkenwell.”

“Would you like me to accompany you?” I asked.

Holmes shook his head. “Thank you, no. You would help me most materially by remaining here, in case there should be any correspondence or visitors to receive.”

I thought this rather unlikely, but perceived that Holmes would rather make this journey alone. I was not entirely unwilling to fall in with his plans, as in truth I felt indolent that morning, and relished the opportunity to idle in our rooms for a few hours. The prospect of another chapter or two of The Mystery of a Hansom Cab had more than a little appeal. So I said farewell to Holmes and settled myself in my favourite chair with Mr. Hume’s excellent story.

I was to be disappointed, however, in my fancy for a spell of idleness, for Holmes turned out to be correct in his prediction of both correspondence and visitors to our rooms. I had not been reading for more than twenty minutes when a telegram arrived. It was from Beresford Lamb, who wrote as follows:

New Development. Coming Baker Street Soonest.

I tried to settle to my reading again, but my concentration had been broken and I had hardly turned another page of the mystery before I heard a cab in the street, and within a minute the great author was again in our sitting room.

“Thank you,” he said when I had taken his hat and cane. “Dr. Watson, I have received another frightful letter. Is Holmes not here to help me?”

“He will be back presently,” I said. “Will you wait?”

“I wish I could speak with him now,” he replied. “I have an appointment with my publisher in a quarter-of-an-hour and had hoped to see Mr. Holmes at once. May I leave the letter with you, and return later to discuss the matter with Holmes?”

“Certainly.”

Lamb handed over a small buff envelope which had been rather carelessly torn open. It bore a penny stamp and Lamb’s name and address in Endell Street written in what looked like the same hand as the letter we had seen the previous day.

“I must depart if I am to make it to Bloomsbury in time, and so I bid you farewell, Doctor. Please do read the letter. I will return after lunch to discuss it with Holmes.” I returned his hat, coat, and cane to him and, with a nod of farewell, the author quitted our rooms.

I felt, a little ruefully, that it was my lot in this case to read important correspondence intended for other men, but I drew the letter from the envelope:

Bastard, prepare to meet your maker! So end all murderers! I see before me every moment the sweet face of that innocent girl whose life you have ended with as much certainty as if you had killed her with your own hands. Indeed, you did just that, albeit your weapons were pen and ink instead of the power your grip. Damn you for the Dashing Carman! Damn you! Your life is forfeit, and I will take it, for Ellen’s sake.

Your most bitter and determined enemy

Tom Charlett

I examined the thing closely. It seemed in every respect the brother of the previous letter. There was the same heavy pressure of the pen which had scored and torn the paper, as if the writer were squeezing out his fury through the nib, and there was the familiar watermark of Joynson. I put the letter aside, all thoughts of reading Mr. Hume’s narrative now quite expelled from my head by the real mystery which lay before us. I turned the matter over in my mind, but as so often when I considered the tangle of evidence which Holmes seemed to cut through with such ease, I found only questions which I had no power to answer.

Holmes returned to Baker Street shortly before lunch. He threw off his coat and hat and wiped his face with his handkerchief. “I have endured two cab journeys,” he said “and a painful interview with the bereaved tanner of Ray Street, on one of the hottest days I can remember. I have also smoked no fewer than seven cigarettes and my mind has turned upon our little problem.”

“I have had a busy morning myself, having received Mr. Lamb. He has been sent another threatening letter, which he left with me, and promises to return to talk with you after lunch.”

“Well, well,” said Holmes rubbing his hands together. “How very interesting.”

I handed over the buff envelope and Holmes examined it and its contents carefully for some minutes. Then he took out the earlier letter from Charlett and laid the two side by side upon the table, comparing first the paper, then the writing.

“Most singular,” he said. “Now, before Mr. Lamb joins us, let me tell you of my little outing this morning. I found Charlett’s tannery in Ray Street a very superior establishment. He is a tanner, leather-dresser, saddler, and felt-manufacturer. But he is a ruined man, quite broken by the loss of his daughter. He is certain that the stories she read of romance and elopement had a strong influence on her decision to defy his wishes with Mr. Smith, and blames these stories, their authors, publishers, and illustrators—he particularly derided the last for their depictions of pretty heroines in the arms of handsome soldiers and the like—for the loss of his daughter.

“But, although he knew well the story of the Dashing Carman from his daughter’s effusions on the subject, I could not persuade him to name Mr. Lamb as the architect of his misfortune. I asked him plainly if he had written Lamb a letter, and he denied it. I contrived too to glance at some specimens of his handwriting, which was clearly different from that we see here.” He indicated the two letters which still lay side by side upon the table. “Yet that may signify very little, for a man may write memoranda in a quite different temper and style from that he would use for a furious threat to a hated enemy. That he denied writing the letter is also far from conclusive. Our interview was interrupted, as I rather expected it would be, by the arrival of Lestrade and a constable who arrested Thomas Charlett on suspicion of the murder of his daughter and of Elias Smith. Charlett greeted this turn of events with horror, and I confess I felt considerable sympathy for him, for I had put the idea into Lestrade’s head.”

“I noticed your doing so,” I said.

“I regret having added to his woes,” Holmes replied. “But, since my return cab-ride and those seven cigarettes, I am all the more convinced that it was necessary.”

“You believe him guilty then?”

Before he could answer there was a ring on the bell, followed by footsteps and a knock at the door. It was a fresh-faced police constable bearing a large cardboard box containing the clothes and other property of Ellen Charlett. Holmes wrote the lad a receipt and, when he had departed, slit open the box with his pocket-knife. The contents were very much as Lestrade had described them. The book he had mentioned was an edition of Jane Eyre, and the magazines were copies of Blackwood’s, both including episodes written by Lamb. Holmes examined these objects and the girl’s clothes with minute care.

“Look here, Watson,” he said, pointing to the hem of a dark blue dress. I looked and saw, adhering to the fabric, a smear of white crystals.

“Salt?” I suggested.

“Possibly.” He carefully scraped the crystals into an envelope with his knife, then re-packed the box, which he took through to his bedroom. “Now perhaps you would call on Mrs Hudson for a cold luncheon,” he said.

After lunch, while we sat smoking, we heard again the doorbell and the now-familiar tread of Beresford Lamb in the passage. When the pleasantries were over, Holmes invited our guest to take a chair and asked him a somewhat surprising question.

“Why,” he said, “did you think you could deceive Sherlock Holmes?”

“What do you mean, sir?”

“The letter you brought Watson this morning was a forgery, was it not?”

Lamb sighed. “I should have known better,” he said. “But how did you know? I thought I had done it rather well.”

“There are six points in the handwriting alone which mark the two out as different. The style of the second is more literary. But the most obvious suggestion that the two were not written by the same hand is that the writer has apparently learned to spell correctly in the few days between.” Lamb looked crest-fallen. “Why did you do it, Mr. Lamb?”

“I confess I thought you were not taking the matter seriously enough. I detected some doubt, even levity, in your manner, and though I feigned as much indifference as I could, I have been very much afraid for my life, and felt that a second letter from Charlett would concentrate your mind and powers upon my problem. I am sorry, Mr. Holmes. I should not have done it.”

“No doubt you should not have done it. But it is done. Did you do as I advised and tell the police of the letter?”

“I did, and they promised to protect me. A police constable has been stationed in Endell Street each night, and another will make a special patrol of the area during the day.”

“That is good. But these precautions will now be withdrawn, for Thomas Charlett has been arrested for the suspected murder of Elias Smith and his own daughter.”

“Then the case is solved?” cried Lamb.

“Not quite. Watson and I must find Elias Smith, dead or alive, to bear witness to the killer’s guilt.”

“I wish you the very best of luck with your quest,” said Lamb. “But my own mind is quite at rest as a result of what you have told me. Thank you.”

“We still have a good deal of evidence to collect and analyse.”

“Indeed,” I said. “Barely an hour ago we received—” My words were interrupted by a low groan from Holmes, and I looked round in time to see him crumple sideways upon the table then crash to the floor taking with him a vase of flowers which Mrs Hudson had placed there that morning. I rushed to his side. He was dreadfully pale and my first thought was that the day’s heat and excitement had been too much for him after the huge stresses of his recent cases. It took me only a few seconds, however, to realize what he was about.

“Is Mr. Holmes ill?” asked Lamb.

“I am afraid so,” I said. “His health is still poor after his encounter with Baron Maupertuis, and I fear he has overstretched himself. He needs rest now. Perhaps you would leave us and I will help him to his bed.”

The instant Lamb had departed, Holmes sprang up from the floor.

“I perceive you wished to stop me telling Lamb about the box of Ellen’s things,” I said, nodding towards the bedroom. “But why? Surely you cannot suspect Lamb? Is not forging this second letter just what an innocent, but terrified, man would do?”

“For the moment I will say only that I wish to keep Mr. Lamb innocent about the details of my investigation. My next task is to identify the crystals found on that dress, and I would ask you to leave me alone with my apparatus for a few minutes to achieve that end. Thank you.”

I sat beside the fireplace while Holmes repaired to the stained table at which he conducted his chemical experiments and lit his burner. He took out the little envelope of crystals and began to work on them, first tasting a few on his finger tip, then placing a few more upon the handle of a spoon and passing it through the flame, which briefly turned purple. Then he mused for a minute or so, and finally ground up the last of the crystals and mixed them with two other chemicals drawn from his numerous bottles and jars.

“Come, Watson, and observe the final proof,” he said. I stood beside him as he scraped the tiny mound of black powder he had made into the bowl of a spoon, and then touched a lighted match to it. There was a flash and a hiss, and a tiny genie of smoke rose from the spoon. It had an unmistakable odour. “Et voilà tout. Potassium nitrate.”

“Gunpowder,” said I.

“Quite. I knew it was a Potassium salt by the taste and purple flame. Presuming it was a common compound, it could not have been the chloride because that is hygroscopic and would not have remained as crystals, so it had to be the sulphate or nitrate. The easiest way to tell which was to make gunpowder with the sample—if it fulminated it was the nitrate and if it was inert then it was the sulphate. Saltpetre was, in fact, what I expected to find. But the test is proof positive. And now I must again leave you to amuse yourself for a little time, while I make a further enquiries. We may bring the business to a conclusion this evening, when I hope you will accompany me in the adventure. I will either return to collect you, or send for you, if you are you willing to assist me.”

“I most certainly am.”

“Until this evening, then.”

It was a long and weary wait. The heat of the afternoon was oppressive, and though I tried to bend my mind back to The Mystery of a Hansom Cab, I was constantly distracted by thoughts of Ellen Charlett and her sad fate. I ate a little supper. Soon night fell. It was past nine when I finally heard from Holmes. He sent a telegram which ran thus:

Meet 17 Buckler Street Woolwich. Ten. Bring Revolver.

I collected my pistol, drew on my coat, and went out into the street to find a cab. When I arrived at Buckler Street it was a little before ten. The sky was still not quite dark, but the streetlamps were lit and I could see Holmes on the street-corner, apparently lounging against a pillar-box while he smoked a cigarette.

“You see there,” he said when I had joined him. “That warehouse?” He indicated a brick-built building. I nodded. “I hope you will not mind breaking an entry in a good cause?” Again I nodded. “I have been watching, and there is no one there now, but we can expect our bird to return to the nest before too long, now that night has fallen.”

The door of No. 17 was heavy and locked both with a padlock and a mortice-lock. Holmes produced a set of burglar’s tools, and quickly picked the padlock and opened it. The mortice-lock proved more difficult, however, and he had to unscrew the plate of the mechanism before he could release it.

“It is important,” he whispered, “that our man does not suspect we are inside when he arrives, so we must leave no traces. I will slip in and open that window. Then I will close the door and while I lock it perhaps you would re-fasten the padlock, then climb in by the window?” Yet again I nodded, though I did not much fancy the window, which was narrow and nearly six feet from the ground. Nevertheless, once I had completed my task, I managed to scramble up and squeeze myself in, and close the window behind me. I found Holmes working by a narrow blade of light from a dark-lantern, relocking the door from within by reconstructing the lock.

We were in a small store-room which appeared to be empty, save for a few piles of rotting timber, perhaps once floorboards or ship’s timbers. At the far end was a blanket, nailed up as a curtain, and Holmes nodded towards this. Beyond was a doorway into a gloomy space which smelt damp and acrid. Once through Holmes said, “I think we might risk a light here, as there are no windows.” He lit a dark lantern and the place was flooded with light. Ahead of us lay a short brick-lined corridor with three chambers leading off each side. We walked slowly along and Holmes directed his lamp into each in turn. In one was a workshop, with a carpentry bench, tools strewn about and planks of timber leaning against the wall. In another was a bed, with a night-stand and dressing-table. In the third was a desk bearing books, papers, and a typewriter, with a bookcase and two chairs beside. In the fourth was a modest larder of tinned and preserved foods, a table and chair, and some plates and cutlery. In the fifth was a motley collection of objects—two bicycles, various trunks and boxes, several children’s toys, and a great stuffed bear. The last room contained, however, a truly astonishing sight. When Holmes swung the beam of his lantern into the space I could scarcely believe it.

“Good Lord,” I whispered. “It must be the Paradol Chamber!”

Before us stood a wooden cabinet, six feet tall and three feet wide, mounted upon wheels. It was painted deep red and decorated in blue and gold, just as the Chamber had been described in Blackwood’s Magazine. When we opened the door, we found the interior covered with black velvet. Holmes reached in and pushed at one side of the central panel, which began to revolve.

“Surely,” I said, “There cannot be someone in there?”

“I doubt it,” he replied, and was proved correct. The hidden compartment of the box was empty, but, when Holmes directed his lamp at the floor, we could clearly see the holes drilled there and I could detect still a faint odour of chloroform coming from below.

“What does it mean?” I asked.

“Little in itself,” he replied. “But I believe we will find something more conclusive.” We returned to the room which was equipped as an office and Holmes began to search through the papers, then the contents of the desk drawers. From the bottom drawer he drew forth a pair of black patent leather ladies’ shoes. They seemed ridiculously small, like a child’s.

“This, I think, will be enough to convict our man,” he said. “And now, we must wait for him. You have your revolver? Excellent.”

We took our places on the two chairs beside the desk, and Holmes shuttered his lantern. I feared we might be in for a long wait, but I was happily in error, for only fifteen minutes had passed before we heard the crunching of a key in the great lock and footsteps entering the outer room. Then a gas jet was lit in the corridor and a tall figure stood in the doorway before us. Holmes uncovered his lantern, and I drew my revolver. Beresford Lamb uttered a foul oath.

“I am afraid we have you, Mr. Lamb,” said Holmes. “My friend has a revolver and will not hesitate to use it, and I have these shoes, which I am sure Mr. Charlett will identify as having belonged to his late daughter.”

“May I light the gas?” said Lamb urbanely.

“I will do it,” said Holmes. He did so and then shuttered the lantern again.

“Now my good friend Watson will remain here, keeping you covered, while I fetch those forces of law and order which you so despise. Did you lock the outer door behind you?” Lamb thought for a moment, then nodded. “Then be so good as to throw me the key—Watson, watch him!” Holmes caught the key and slipped past our prisoner into the corridor. A moment later I heard the outer door open and the sharp note of a police whistle.

Lamb smiled, then moved very slightly towards me.

“Remain perfectly still,” I said. “Or I will shoot you.”

“I doubt that,” he said. “You are a man of feeling, unlike Holmes, who is a mere reasoning machine. You would not harm a fellow creature, especially one who is innocent.”

“You are quite right,” I replied. “I would not harm an innocent. But I do not believe you are any such thing.”

“Oh, I am,” he said. “I am the victim of a most unfortunate error on Mr. Holmes’s part. I beg you to believe me. Whatever evidence he has found he has misunderstood. . . . You will admit that it is possible.”

I felt that it was, but was in no mood to argue the toss so said nothing more.

“Now let me show you something, something which will convince you of my good intentions.” He began to reach towards the left inside pocket of his jacket.

“What is it?” I asked.

“It is a letter from Ellen Charlett. The truth is that I did know her, as a friend. She wrote to me after one of my stories touched her, and we struck up a correspondence. Her letters told of how she feared the anger of her father and wanted to run away with Smith to a safe place. I helped her with money. But her father found her all the same. This letter proves it.”

“Move your hand no further,” I said, “or you will find yourself quite unable to move it.” He ceased the gentle creeping of his hand towards his pocket. “If you are innocent, how did you come by Ellen’s shoes?”

“I confess I took them from her room, but after she had been killed. I went to the hotel to give her money, and found that Charlett had been there before me and strangled her. I took her shoes for a base reason, I am afraid—I intended to plant them in the possession of her father, so that the evidence against him would be all the stronger. I wanted him brought to justice. Only let me show you the letter, and you will see it all.”

I thought this story convincing. He could see I was wavering in my resolve, and his hand moved slowly again towards his pocket, while he smiled. His face was a picture of honesty and candour. But at that moment I recalled the shoes, how small and pathetic they had seemed, and I squeezed the trigger and fired.

I am a good shot, and the bullet caught Lamb squarely in the right shoulder. With a terrible cry he was thrown back onto the floor in the corridor. A moment later Holmes rushed in followed by a constable.

“I should not have left you alone, Watson” he said. “Are you hurt?”

“Not at all,” I said. “Lamb told me he had a letter that would prove his innocence in his left breast pocket . . .” Holmes reached gingerly into the pocket and drew out a small, pearl-handled revolver.

Lamb groaned. “Your friend tried to kill me,” he said.

“Nonsense,” said Holmes. “Had he tried to kill you he would have succeeded. Now stand up and let me search you while Watson keeps you covered. I do not think you will twice doubt his determination in the matter.” Lamb dragged himself to his feet, and Holmes went through his pockets, removing nothing else but a leather-bound notebook and gold-plated fountain-pen.

“Very well,” said Lamb. “You have captured and wounded me, and I will tell you all. But not before the police inspector arrives. I want my story properly recorded, and known across the world.”

“I doubt very much that there would be a word of truth in your story. Let me propose an alternative. When the inspector arrives, I will tell your story and you will kindly correct me if I go wrong in any particular. Now sit here—Yes, against the wall—and I will hold the pistol while the Doctor examines you. Do I hear the delicate footsteps of the excellent Lestrade approaching?”

Indeed, there was a thunder of footfalls in the outer room and Lestrade and two further constables burst into the corridor. Lamb sat down against the wall and I gave Holmes the revolver while I examined the wound that I had inflicted. The bullet had passed through the shoulder-blade, shattering it and the collar-bone, and out the other side. The wound was not life-threatening, but was no doubt very painful and would leave Lamb with a permanent weakness in his right arm. I did not have my bag with me, so that all I could do was apply a compress with a clean handkerchief. Holmes handed the revolver back to me.

“So you’ve shot him,” said Lestrade, stating the obvious. “Why?”

“Let me enlighten you,” said Holmes. “It is a grotesque story which your constable may care to record, for it contains a full confession. Beresford Lamb was not given that name at birth, but assumed it as one of a number of personalities in his life of crime. It became, perhaps, his dominant persona. Lamb, the successful writer, the great man of letters, famous, and now rich too because of the popularity of his stories. He has recently bought a new house in Endell Street on the profits of his writing. No doubt he has a considerable talent with his pen, but what makes Lamb remarkable is that he bases his stories, as far as possible, on realities, and the feelings of his protagonists, especially his villains, upon his own feelings. He is a sensualist, and has, I venture to suggest, so little of what a normal man would call conscience as to be practically devoid of any such virtue. He is probably the third cleverest criminal in London.”

“Twaddle!” said Lamb.

“And possibly the most remorseless. He has also, until now, been able to continue his career, and to write about his crimes quite openly, without detection. That is the genius of the man. His mistake, his final mistake, was to take on Sherlock Holmes. For that was what you intended to do, was it not?”

Lamb made no answer, but gestured towards the desk where we had found the shoes. Holmes retrieved from it a sheaf of typewritten pages.

“It would have been my greatest triumph,” said Lamb. “Or rather, Lord Pinto’s.”

“I see the story is called ‘The Eclipse of the Great Detective’. A very lively title.”

“It is all written,” said Lamb, “all but the last few pages, in which the famous consulting detective fails, and Lord Pinto succeeds.”

“The crime,” said Holmes, looking through the papers, “is the murder of Ellen Charlett. I see you have given her another name, as you have to your failing detective, but the circumstances are identical. A young woman, seduced by an intelligent older man who pretends to be a failed actor, persuades her to elope with him against her father’s wishes. When he has her at his mercy in a cheap hotel, he strangles her and flees into the night.”

“You could never have solved such a crime,” said Lamb.

“I suppose you think that because you see me as a rationalist? For Sherlock Holmes, there must be a rational motive for every crime, while this murder was committed for no rational motive. It was not for gain, or love, or hate, or revenge, or even for expediency. Why did you kill Ellen Charlett?” Lamb was silent. “In the story, I suspect the motive was one of pure sensuality. Your heartless older man merely wished to know what it was like to have a young woman at his mercy, and to take her life with his own hands. He wanted the experience. And that was something you believed I could not understand. Sensual pleasure was part of your motive too—for we must not forget that this murder has been done twice, once in fiction and once in fact. You wanted the experience. I daresay you enjoyed it. But you had two further motives. Firstly, you wanted to live out, to try out, the plot of your story, and secondly, you wished to confound Sherlock Holmes.

“In order for the last motive to succeed, however, I had to be brought into the case, and that was why you came to me with a forged letter in your hand. I could do nothing else but investigate the case, and fail to identify the killer—yourself—while every false move I made was noted and ascribed to your Great Detective, whose defeat was the heart of your story.”

“Quite untrue!” said Lamb. “The heart of my story was Lord Pinto’s success.”

“I knew I was being led a dance, and so I danced, and tried to perform in every way as you wished me to, even leading Lestrade to believe I thought poor Tom Charlett the true killer. I am heartily sorry that I had to do that.”

“I am confused,” said Lestrade. “If this Pinto solved the case in the story, would that not reveal who killed Ellen Charlett?”

A look of irritation came over Holmes’s face. “The story,” he said, “reveals only the name and nature of a fictional character who killed a girl for pleasure, and the cleverness of Pinto in his deductions. It would be clear enough that the case was based on that of Ellen Charlett, but this would hardly be the first time a story had been inspired by a real crime. I believe Mr. Poe wrote something of the sort forty years ago.”

He turned again to Lamb. “You almost succeeded. But I had three clues that guided me, and one scrap of evidence you overlooked. The first clue was in the letter which you forged from Thomas Charlett. I had no way to prove it a forgery, but I believed it was.”

“Come now,” said Lamb. “You must admit that the letter was a masterpiece, a brilliant piece of both writing and forgery.”

“You betray one of your greatest flaws, Mr. Lamb. You are conceited. The letter was good, but it was just a little too florid, too much the work of a man of letters, to be genuine, while at the same time the poor spelling and coarse language was too strong for a man of Charlett’s education and standing. My second clue came when Lestrade told me the name of Ellen’s lover, Elias Smith. I was reminded at once of another Lamb, the poet Charles, who assumed a pseudonym for his essays. What were they called, Doctor?”

“‘The Essays of Elia’,” I replied.

“Quite so. Lamb had suggested to you Elia, and Elia had suggested Elias. Perhaps it was merely the unconscious signature of a self-regarding man of letters. The third clue came with the second letter which you forged. This was a very clever strategy. Your intention was to bring me a letter which was sufficiently unlike the previous one to be detectable as a forgery. When I uncovered the deception, as you knew I would, your stated reasons for undertaking it would do nothing but guide me further from the truth, and quite convinced Watson here of your innocence. However, I saw something else in the second letter, which you may not have considered when you wrote it. Although it was obviously different in a number of respects from the first letter, it was also obviously similar in a number of ways. The hand and language were so similar—as they had to be, if I were not to see immediately that this was a crude fake—that I asked myself how, without the earlier letter before you, you had done it. At that time, you will remember, the first letter was safe within my pocket-book. You either had a truly remarkable memory for handwriting and words, or you had written both letters yourself. Although I could not prove it, I inclined to the latter opinion.

“The final scrap of evidence was a few crystals which I scraped from the hem of Ellen Charlett’s dress. You removed her shoes from the hotel room because your feared there were traces on the soles which might lead me to you, but you missed a very small trace on the hem of the dress which, I will wager, Ellen wore when she last visited you here. The crystals turned out to be of saltpetre. Where would one pick up such a chemical except in a manufactory of gunpowder? There is only one such in London, and it is hardly likely Ellen would have visited the Royal Arsenal. I recalled, however, that some years ago the Woolwich Dockyard had been part of the Arsenal, but had been closed down and many of the warehouses let to private companies. In such a building, where munitions had been made and stored for decades, was it not likely that saltpetre would be found upon the floors, and picked up by the boots and skirts of a visiting lady? I spent part of this afternoon with the agent for the former Dockyard buildings, and learned that only one of them, No. 17, had been rented in recent years—to a Mr. Charles W. Holmes. Guessing a little of Mr. Lamb’s manner of choosing his noms-de-plûme, I suspect the compliment was due not to me, but to the American poet and essayist. So Watson and I came here and found your second home, your lair, in which your crimes were planned, your devices perfected, and your plots written.”

“You have not bested me,” said Lamb. “I am still the better man. That you found me out was sheer luck, Holmes!”

“I would expect you to believe nothing else.”

“What of the Paradol Chamber?” I asked.

“That was an example of Mr. Lamb’s practical approach to the writing of mysteries. He conceived his vain-glorious magician, Paradol—we may perhaps detect another self-portrait here—but had to know whether his device would work in practice. So he built the Chamber. It was an easy task for one who had once worked as a carpenter.”

“How the devil could you know that?” said Lamb.

“When I first shook your hand, I remarked how much larger and stronger the right was than the left. You had clearly not developed such musculature wielding a pen, and I deduced some physical labour. Carpentry was suggested by the fragment of your story which I read, in which the construction of the Paradol Chamber was described in very precise terms. I would further venture to guess that you have worked in the theatre, both as an actor—witness your recent performances in my sitting-room—and in other roles, perhaps as a scenery-builder.” Lamb regarded Holmes with malevolence, but said nothing. “Perhaps you tested the Chamber on Ellen Charlett.”

“I did!” said Lamb. “That was back in February when I had first made her love me, and was initially drafting that great story. I had just told her my real name—well, I had revealed that I was Beresford Lamb, the very writer she admired with such a passion. I swore her to secrecy, and she was willing, eager even, to step into the Chamber and try my experiment. It worked wonderfully. Within a minute she was quite unconscious and I could enter and draw her sleeping body out. You cannot imagine my delight. Ellen came back here many times after that, to serve me. ‘The Eclipse of the Great Detective’ required that we elope—which I effected easily—and that she be strangled by her lover—which was also a simple matter. I brought her here that evening, so that I could tell her the story of the great victory of Lord Pinto over Sherlock Holmes.”

“Did you tell her that you intended to take her life?”

“No, though perhaps she guessed. Had I asked her consent, I am sure she would have given it and offered her throat gladly. But it was important to me that she did not give her consent.”

“You know,” said Holmes, “in some ways, the letters you wrote in the person of Tom Charlett were your most truthful expressions. When you told yourself, ‘You are a bastard and murderer!’ and ‘You are responsible for my Ellen’s death, as surely as if you had strangled her with your own hands’, you were, for once, writing the literal truth.”

“I should kill you for that,” said Lamb in a low voice. “I regret that I will probably not have the opportunity to do so.”

“Probably not,” said Holmes. “After you had taken her back to the hotel and done the deed, you thought to remove her shoes, just in case they bore traces which might lead the police, or an astute sleuthhound, to your door. But you missed the smear of saltpetre on her skirt, and that was your undoing. I wonder if you had another motive for taking the shoes? Did you wish for a memento of Ellen? Or of your sensual experience in bringing about her end?”

“I will not answer that,” said Lamb. “I see that the constable has been taking notes, and there will no doubt be an official report on the case, and perhaps a confession which I shall be called upon to sign. I will do so, but on one condition. That my story, ‘The Eclipse of the Great Detective’, be published in Blackwood’s as it stands, with my confession included as its termination.” There was a moment’s silence. “I had hoped to write more stories. I had a dozen plots in mind—all ingenious, all delightful—but I have done enough that the name Beresford Lamb will live for ever.”

Lamb would say no more, and soon afterwards was taken away by the police surgeon. He stood trial for the murder of Ellen Charlett, and was convicted, but his sentence was commuted to one of life imprisonment as the judge believed him a lunatic. Holmes believed differently. He thought Lamb neither mad nor wicked, but a curious anomaly of nature, a man born without a conscience who regarded his mind, imagination, and senses, as the centre of all things. The case had been a triumph for Holmes’s powers. He had defeated a great intellect in a game played by his opponent’s rules. Thomas Charlett was naturally released by the police, and attended Lamb’s trial, but betrayed no emotion when the sentence was passed. It is said that Lamb continued to write in the asylum, but his stories were always burned on the orders of the Governor. “The Eclipse of the Great Detective” was never published.

For my own part, I returned to our rooms after the adventure, and picked up again The Mystery of a Hansom Cab. I read it to the end, but found it dull and flat after the excitement of recent adventures with Holmes. This set an idea loose in my mind. These stories, these tales of murder and romance, had always an emptiness at their centre. Even those of Beresford Lamb had proved unsatisfying, because they were, in the end, untrue. What if I could write stories, based not on imagination but on fact, on the adventures of Sherlock Holmes, which had often been reported in the press with such scant regard for the truth? Some few years before, I had written a memoir of my time in India and Afghanistan and of my return to England, which had been lost in circumstances associated with the case I later called “The Adventure of Nightingale Hall”. I had included short accounts of three of Holmes’s cases in that lost book. Perhaps now was the time to recall those cases, and seek to publish those accounts, and others. I certainly had notes enough, and fancied I could write as fluidly as Beresford Lamb, and a good deal more honestly. I decided then to try to publish an adventure or two of my own. It did not occur to me until some days later, when I had completed the draft of the first such story, to wonder what on earth Holmes might make of the idea.

The year ’87 furnished us with a long series of cases of greater or less interest, of which I retain the records. Among my headings under this one twelve months I find an account of the adventure of the Paradol Chamber . . .

— Dr. John H. Watson, “The Five Orange Pips”