The Adventure of The Parisian Butcher

By Nick Cardillo

Nick Cardillo has been a devotee of Sherlock Holmes since the age of six. He is the author of The Feats of Sherlock Holmes and his short stories have also appeared in anthologies from MX Publishing and Belanger Books. Nick is a fan of The Golden Age of Detective Fiction, Hammer Horror, and Doctor Who. He writes film reviews and analyses at www.Sacred-Celluloid.blogspot.com. He is a student at Susquehanna University in Selinsgrove, PA.

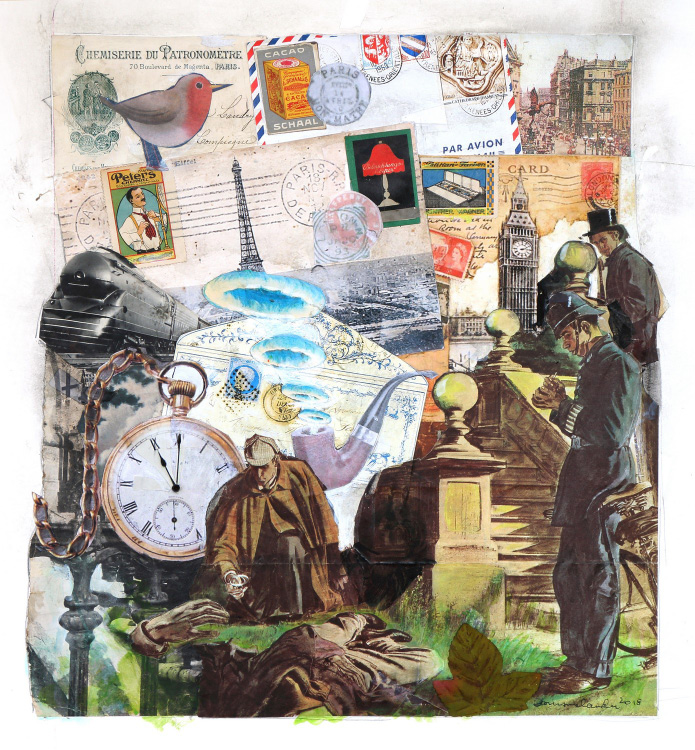

Bruce Helander is an artist, writer and critic. He received a BFA in Illustration and an MFA in painting from the Rhode Island School of Design, where he later served as the Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs. He studied at Yale University for journalism and storytelling, as well as at Harvard, and is a former White House Fellow of the National Endowment for the Arts. He recently received the First Annual Professional Achievement in the Arts Award from Palm Beach Modern + Contemporary and is a member of the Florida Artists Hall of Fame. Helander is a past recipient of the South Florida Cultural Consortium’s award for Professional Achievement in the Arts and has won four separate grants from the New York Foundation for the Arts. His work in represented in over fifty permanent public collections, including the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Whitney Museum of American Art and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, as well as the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. As a critic, he regularly writes for numerous publications such as The Huffington Post, Sculpture magazine, Art Hive magazine and One Art Nation, among others. His illustrations have appeared in numerous publications, including The New Yorker magazine. His most recent books include “Chihuly: An Artist Collects” (Harry Abrams, Inc.) and “Bunnies” (Glitterati Press). He is a seasoned juror and curator of museum exhibitions and serves on the board of the Center for Creative Education. There are two anomalies in the artwork. Can you find them?

Artwork Size: 15” × 14”

Medium: Original paper collage on museum board with embellishments

It has always been my intention to give the public as accurate and complete account of my association with Mr. Sherlock Holmes as possible. However, there have been innumerable times in our career together that I found myself having to alter facts such as names, dates, and places in order to relate matters of a sometimes scandalous or sensitive nature. On other occasions, I’ve found it necessary to hold back an account in its entirety; deciding as I laid my pen aside that it would be for the best that the particulars of some of Holmes’s cases never be exposed at all. Such is the manuscript which follows: One of the few times when I determined it best that the document be consigned to some obscure corner of the Cox and Co. Bank vault, never to see the light of day.

Sherlock Holmes was the very last of men to ever give credence to any sort of sixth sense, so it came as something of a surprise to me one humid, rain-bedewed morning in the late summer of 1886 when Holmes sat back in his chair and said: “I have the strongest intimation that something is wrong.”

I set the paper down on my knee. “Whatever do you mean?” I asked.

Holmes passed me an open envelope. “That letter came to me last evening while we were away,” he said. “It is, as you will doubtlessly notice, postmarked London. However, the writer of that letter is Monsieur Andre Dupont, a wealthy French businessman. Does the name strike your ear as familiar, Watson?”

“I cannot say with any certainty,” I replied. “What does this Monsieur Dupont write to you about?”

“He does not say,” Holmes replied, reaching for his cigarette case. “He was most irritatingly vague. However, he says that he will present himself at our rooms at eleven o’clock on the morrow—meaning, of course, today.”

“Well, I don’t see what makes you so particularly inclined to think that something is wrong.”

Sherlock Holmes lit his cigarette and laid the burnt-out match into the ashtray at his side. “If you would do more than to observe the latest cricket scores in that very paper which you have currently splayed out across your lap, my dear fellow, you would find an article which announces that M. Andre Dupont will be arriving by the one o’clock boat from Paris, as he is conducting some business with a few prominent English industrialists.”

“Which means that Dupont has been in London for a day already.”

“At the least,” Holmes replied. “Either M. Dupont had some business of a more illicit nature to attend to in the city, or he is very much in fear for his life. The fact that his arrival in the city has now been documented leads me to believe that he will have to go to some extremes to conceal his earlier arrival. By my estimation, a lookalike shall be disembarking from the one o’clock boat in M. Dupont’s stead.”

Holmes clicked open his fob watch. “It’s nearly eleven now,” he said. “If you would be so kind as to stay, Doctor, you could be of invaluable assistance.”

I told Holmes that there was nothing that I would rather do than aid him in any way I could. No sooner had Holmes exclaimed, “Capitol!” and clapped his hands zealously together then did we hear the bell below chime. I could hear the sound of someone at the door conversing with Mrs. Hudson in the foyer and, a moment later, when our landlady drew into the sitting room, Holmes beamed at her.

“You may show M. Dupont up at once, Mrs. Hudson. His visit is not an unexpected one.”

“I beg your pardon, Mr. Holmes, but it is not M. Dupont who is at the door.”

Holmes knit his brow in confusion. “Who is it then?”

Mrs. Hudson produced our visitor’s card and handed it to the detective. He read it, his face clouding further. Then, without a word, he gestured for her to bring the client in.

“Well,” I said, once Mrs. Hudson had gone, “who is it?”

“The card is most certainly that of M. Andre Dupont,” Holmes said passing it to me. “But, as you will perceive, written upon it are the words: Alexandre—Valet.”

“Why should Andre Dupont send his valet to you instead of coming himself?” I asked.

Holmes shrugged his shoulders. “I hope that the man shall endeavor to answer that very question.”

Our landlady returned with a tall, lanky man in his early fifties. He was well-dressed, though I figured that the dark coat and bowler hat which he carried could not have been in the slightest comfortable, especially as the late summer weather had turned the atmosphere thick and cloying.

“I would not be incorrect in assuming that you have come on behalf of your master?” Holmes asked the servant.

“That is correct, sir,” the man replied. He remained stiff as a board, totally unmoving as he spoke. “M. Dupont had all intentions of calling on you himself this morning, per his letter, but he decided otherwise at the very last moment. He would, however, be most grateful if you would accompany me to my master’s home. He is still most anxious to speak with you.”

“This business must be one of the utmost severity,” Holmes said, more to himself than anyone else in the room. “Very well. I shall come with you, provided that Dr. Watson is allowed to accompany me. He acts as my associate in all my cases.”

The valet nodded his head slightly. His total lack of movement made the man appear to be some kind of statue. “That shall be quite alright, Mr. Holmes.”

“Excellent! Then the Doctor and I shall join you in the foyer in precisely three minutes.”

Holmes quickly set out gathering up his things and, once we had made our way downstairs, we climbed into a waiting four-wheeler and soon found ourselves hurtling through the teeming streets of the metropolis.

“Tell me, Alexandre,” Holmes began, “how long have you been in M. Dupont’s employ?”

“This autumn will be my fifteenth year.”

“Would you describe your relationship with M. Dupont to be a close one?”

“I should think that no man knows my master better than I,” the valet replied.

“And you have no idea in the slightest what could be troubling him so?”

For a moment, a look of fear came into the valet’s dull, grey eyes, before he said quite emphatically: “No, sir. I cannot think of anything.”

I noticed the look and flashed Holmes quick glance. He locked eyes with me and I knew that he too had perceived the valet’s clumsy attempt at deception.

Our cab drew up outside of a very well-appointed house, tucked back behind a mighty oak tree which grew out of the well-manicured front lawn. The valet produced from his coat a ring of keys and, once inside, he divested us of our hats and led us into a large, open sitting room. The room was lined with expensive-looking oil paintings on three of its walls, with the fourth taken up by a stylish set of French windows which looked out onto a neat stone veranda. At the furthermost end of the room was a large fireplace, before which stood the man I took to be Andre Dupont. He was tall and lean, and not a day over forty—though he looked considerably younger—sporting an elegantly waxed mustache. He was well-dressed in an expensive black suit. He looked as if he was destined to be in that room, as though he were one of the subjects of the portraits on the wall that had come to life, just to add flair to the space.

“Ah, Mr. Sherlock Holmes,” he said, with the slightest trace of a French accent permeating his words. “Thank goodness you have come.”

“M. Dupont,” said Holmes as he moved further into the room to shake hands with the man, “you need not be a detective to figure that you are quite distressed about something.”

“I should imagine that my urgent letter and my subsequent behavior was enough to convey that to you.”

“Indeed,” Holmes said, “I have seldom encountered so curious a starting point to an investigation in my days as a consulting detective. Dr. Watson, my friend and colleague, can testify to that point.”

I shook hands with Dupont and verified Holmes’s words, which seemed to put the aristocrat to some ease.

“I am in fear for my life, Mr. Holmes,” Dupont replied. “Please, gentlemen, sit. I shall tell you the story through.”

Dupont took a seat in a wing back chair while Holmes and I took seats on opposite ends of a plush-looking settee. After he had offered us cigarettes, Dupont leaned back in his chair.

“I am a wealthy man,” he began. “As such, I have garnered a few enemies in my time. Business rivals have publicly threatened me, and I have more than once in my life avoided being brained by thrown rocks. I have developed a thick skin. However, petty threats and stones pale in comparison to the threatening letters which I have received in the past few weeks.”

From his inner beast pocket, Dupont withdrew two envelopes. “The first,” he continued, “was delivered to my home in Paris a week ago. At first I thought that it was yet another threat from a business rival. The message itself was short and quite vague: ‘Your time on earth is running short.’ It was not until I examined the note more deeply did I truly begin to fear for my life. You see, Mr. Holmes, this message was written in blood.”

I sat upright in my seat suddenly. Dupont passed the letter to my friend. He took it and observed it first with the naked eye before peering at it through his convex lens.

“It is genuinely blood,” my friend said length. “You will doubtlessly recall, Watson, that when first we met I was in the midst of developing a test to determine whether a substance perceived to be blood is actually blood. The congealed quality of the substance is enough to tell me that it is not ink.”

“Naturally, I was scared out of my wits,” Dupont continued. “I made sure that all the doors and windows of my home were locked. I began to carry a gun on my person and slept with it under my pillow. My wife, Michelle, started to question me about my curious behavior, but I did not wish to disturb her.

“However, my genuine terror only increased when, shortly after the arrival of that first letter, my pet dog disappeared from outside my own home in Paris. I feared that he had run away, but after searching for little more than an hour, my staff and I discovered that it had been slain. My wife knew something was amiss and confronted me that very night. I showed her the letter which I had received and together we believed that it was for the best that we leave Paris. I did not wish to make public my intent to travel to London, but it somehow it ended up in the majority of both Parisian and British papers. It was for that reason that I plotted to arrive here in London a full two days before my public arrival this morning. We traveled with some of my most trusted staff so we should want for nothing here in London. I even managed to hire a man with a similar resemblance to me to publicly be seen leaving the ship. I was taking no chances, whatsoever.

“I thought, Mr. Holmes, that I was safe. And then, yesterday morning, I received yet another letter. It is postmarked London.”

He handed the second envelope to Holmes. The threatening message was, once again, terse and to the point: “Death is Coming For You.”

“It, too,” Dupont said grimly, “is written in blood.”

He drew in a deep breath, attempting to calm himself. “Whoever has sent me these letters knew of my flight to London,” Dupont continued. “He knew that I would leave early and has dogged my heels across the Channel. Mr. Holmes, I beg of you. Please protect me.”

“I am not a common bodyguard,” Holmes retorted, more coldly than I believed was warranted. He handed the letter back to our client, and eased back in his chair, crossing one long leg over the other in a deceptively languid manner. “I shall, however, do my utmost to help you in unmasking your stalker. However, I must insist upon one thing M. Dupont: You must reveal to me all you know.”

“I have told you everything.”

“I do not think so,” Holmes icily replied. “You identified your stalker as ‘He’ a moment ago, almost as though you know precisely who is responsible for these acts against you. If you gave me some indication of who this man might be, I can go a long way towards clapping irons about his wrists.”

Andre Dupont sucked in another deep breath. “I know of only one man who would have cause to wish such misfortunate on me,” he murmured. “But that man is dead. I am sure of it.”

“Nevertheless, tell me about him M. Dupont.”

Dupont leaned back in his chair and, for an instant, the ghost of a smile crossed his mouth. “You will notice,” he began, “that I am a collector. These paintings on the walls are all originals. Are you an art enthusiast yourself, Mr. Holmes?”

“I can appreciate a Bond Street art gallery as well as the next,” Holmes replied. I cast my friend a quizzical glance, silently asking him what this could possibly have to do with the matter at hand. Holmes met my eyes and seemed to silently address me, saying that all would become clear in time.

“I have amassed something of a collection,” Dupont continued, rising from his chair and moving to a small, elegant-looking bureau in the corner of the room. From his waistcoat pocket, he withdrew a key, and inserted it into the lock. He opened a cabinet door and removed a small case about six inches across, wrapped in a light cloth.

“I have always had a fascination with art,” Dupont continued, “and from time to time, I have been captivated by the oeuvre. I confess, that I have always been riveted by Bosch’s depiction of Hell in The Garden of Earthly Delights. I suppose that is what led me on the path to having an eye for the fantastic and the unique.”

Dupont accented the last word as he removed the cloth from the case. What lay beneath was a neat, glass container. It was the contents of that container which turned my blood to ice.

Within the case sat a neatly severed human hand.

Though I have a strong stomach and am immune to much, the sight made me feel dizzy for a moment. Perhaps it was the showman-like air which Dupont had adopted in revealing to us his unique piece of art. I looked to Holmes, but his face was cold and unreadable.

“Whose hand is this?” Holmes asked at length.

“The man’s name was Jacques Bonnaire,” Dupont replied. “He was a close friend of mine for many years until, after my wife and I married, he attempted to make love to her. I caught him in the act and shot him on the spot. He was severely wounded and, as he lay bleeding, I told Michelle to call for the police at once. When she had gone, I must have lost my head, Mr. Holmes, for I took up a knife and cut off his hand. I just wanted to make a point to the blackguard not to cross paths with me anymore. The police arrived and dealt with the matter. Luckily in France, crimes of passion are leniently treated under the law, and Bonnaire was hauled away a hospital. I have not heard of him since, but I cannot imagine that he survived his wounds.”

Sherlock Holmes remained silent. For once, I could read Holmes’s cold, inscrutable eyes like a book and it came as little surprise to me when he opened his mouth a moment later and said, “Frankly you disgust me, M. Dupont and I shall have nothing to do with you.”

“But what about the threats to my life?”

“You seem like the type of man who is quite capable at defending himself,” Holmes retorted. “And, should you be too much of a coward to face your threats, then do what cowards do best: Run. You have shown yourself quite adept at that as well. Run away. Perhaps, back to Paris. Surely, Jacques Bonnaire will have quite a time crossing the Channel once again minus a hand and a bullet in his chest. That is my advice and I shall do nothing else but offer that alone. Good day, sir.”

So saying, Holmes spun around on his heel and started out of the room.

When I managed to catch my friend, he was already standing outside hailing a hansom back to Baker Street. Once we were ensconced in the belly of the cab, I could see Holmes silently gnashing his teeth.

“It is said that you can judge a man’s character by the company he keeps,” he said “and I should surely never wish to keep company with M. Andre Dupont and his penchant for hacking off the hands of his rivals.”

“I do not blame you, Holmes,” I said comfortingly.

Holmes drew in a deep breath and sighed. “But I cannot help but think,” he murmured, “that I may have been hasty in my judgment and I have sent a man to his death. I fear that if my imitations prove to be correct once again, then M. Andre Dupont’s death may very well weigh on my conscience.”

Holmes refused to speak on the matter for the next few days and, it was only as I sorted through the first post of the day three days later, that the business of M. Andre Dupont re-entered our lives.

“Postmarked Paris,” I said as I held a letter aloft. I read the return address. “Inspector Durand. I say, Holmes, isn’t that—”

“Yes,” Holmes interjected. “Inspector Durand was the most competent of investigators who we ran across during that bad business at the Paris Opera House five years back. Please, Watson, do me the service of reading the letter out.”

I settled into my chair and opened the letter. It was written in an authoritative hand:

Mr. Holmes,

You will no doubt remember my name well. Though we seldom worked side-by-side so many years ago, I considered it a pleasure to have seen you in action. You have developed something of a following here on the Continent as your name has begun to appear in the press with frequent rapidity.

I wish then that it could be under better circumstances that I write to you, and I severely hope that when you receive this letter that you are able to drop whatever it is that currently occupies you and join me in Paris. To put it briefly, it is murder—the murder of Andre Dupont, the wealthy businessman. If it were only a routine investigation, I should not think on troubling you as I do. However, the savagery with which this murder was committed is unlike anything I have seen in many years of working as a police inspector. Both M. Dupont and his wife, Michelle, fell victim to the murderer. They were stabbed to death and discovered with one of their hands neatly cut off.

“Good Lord, Holmes!”

The inspector’s words seemed to cut into me like a knife as well, and I felt a shiver run up and down my back. I hardly had time to register Holmes bolting from his chair and perusing the train directory.

“The boat-train to Paris leaves in two hours, Watson,” he said. “If we make haste, we can still catch it.”

“Don’t you want to hear the rest of the letter?”

“On the train,” Holmes said, as he rushed off to his room with a frenzied wave of his hand. “We must act while the game is still very much afoot.”

The next hour disappeared in a flurry of packing of bags. Holmes rushed off a telegram replying to Durand, and we soon found ourselves charging across the station platform and ducking into a first-class carriage. I was only catching breath as the train became wreathed in smoke and pulled out the station. Once we found ourselves hurtling across the English countryside, I cast a glance across to my friend. He stared out of the window at the passing fields, his face betraying no discernible emotion. I wondered if the deaths of Dupont and his wife were, indeed, weighing on my friend’s mind. Knowing him, he would blame himself for their violent ends. I was almost inclined to say something in an attempt to break him free from his reverie, but I decided against it.

We passed the voyage in relative silence, broken only by Holmes pressing me for more information from Durand’s letter. After I had read a part through, he would sit in silence and contemplate the scant words for what masqueraded as hours before urging me to continue.

Inspector Durand had explained that the room in which M. Dupont and his wife were discovered was the locked sitting room of their well-appointed abode, located on a well-to-do road in the middle of Paris. The bodies had been discovered by the valet, Alexandre, who had contacted the police at once. Aside from a servant girl, there were no other persons in the house.

A silent passage by boat was followed by another sojourn by train. It seemed as though the foul weather which had descended on London had followed us to the Continent. Rain lashed the train compartment windows and, when we finally arrived in Paris, we found ourselves rushing to hail a cab and avoid the deluge. Holmes had done us the service of booking a last-minute set of rooms at a hotel and, after we checked in, he sent off another telegram to Inspector Durand announcing our arrival. It had been a long, exhausting day, and at the end of it I found myself famished. I ate a small repast, and was not surprised—and not pleased—that Holmes refused to take any nourishment. I had just gathered up my plates and silverware when we were arrested by a knock on our door.

Holmes answered the call and found the familiar figure of Inspector Durand in the doorway. The half-decade since last we had met had been good to the inspector. He was a tall, lean man, broad-shouldered, and rather statuesque in appearance. He had a long face with deep-set eyes, and a shock of fair hair atop his head. He furled his umbrella while my friend relieved him of his coat, gesturing for the representative of the Parisian police to draw up before the fire.

“You look as though you could use a drink, Inspector,” I said as I poured him a brandy from the sideboard. He accepted the libation all too readily.

“Merci, Doctor,” he said, draining his glass. “It has been quite a day.”

Holmes took a seat opposite the inspector and lit a cigarette. “Dr. Watson did me the service of reading the details of the case,” he began. “Are there any particularities which you were unable to convey to me?”

“None, M. Holmes,” Durand replied. “All of the facts which are in my possession were highlighted. And, alas, very little has been gained from the investigation.”

“I assume that you have conducted an examination of M. Dupont’s papers and personal possessions?” Holmes asked.

“Why, of course,” Durand said, appearing slightly injured by Holmes’s question. Perhaps the inspector did not know Holmes well enough to understand my friend’s low opinion of the official police.

“Did you happen to find any mention of a man called Jacques Bonnaire?”

Durand considered for a moment. “No,” he said. “Why? Who is this Jacques Bonnaire?”

“At present,” Holmes replied, blowing a ring of smoke about his gaunt head, “he is a suspect of particular interest. However, as it is a capitol mistake to theorize before one is in possession of all the facts, I shall do my utmost not to let the lamented M. Bonnaire enter into the investigation at this time.”

“But if he could have an impact on this case,” Durand said, “it would be a grave miscarriage of justice not to pursue this particular thread. Who is Jacques Bonnaire?”

“Holmes and I were contacted by M. Dupont in London three days ago,” I began. “Dupont had been receiving a number of threatening letters—first, here in Paris, and again in London. He believed that they were sent by a man named Jacques Bonnaire, his one-time friend who tried to seduce Dupont’s wife. In retaliation, Dupont shot Bonnaire and cut off the man’s hand. Dupont lost all traces of Bonnaire after the incident, but seeing how these murders have a strong link to the incident involving Bonnaire, it is understandable how he should become a suspect.”

“I should think so!” the inspector exclaimed. “I shall make it a priority to look into this Jacques Bonnaire character.”

“No, Inspector,” Holmes retorted rather coldly. “You should make it a priority to allow Dr. Watson and me to examine the bodies. I assume they have been taken to the mortuary? Excellent. Though the hour is rather late, I can think of no time like the present to visit the morgue.”

In short order, the three of us had donned our hats and coats and had stepped into the street. The deluge had lessened and a mist was falling upon us. Inspector Durand hailed us a cab and, as we climbed inside, a palpable silence descended over us. I watched as Holmes peered out at the passing rain-soaked city. The City of Light took on a haunting yellow glow as the undulating flames of gas lamps mingled with the wall of fog and mist into which our carriage trundled.

We alighted before a small, stone building tucked on a side-street. Inspector Durand eased open the door and we stepped inside. The smell of death was overwhelming and I clapped a hand to my nose. Though I have in my time been in the presence of death and decay—as both a soldier and a doctor—I would never be able to become immune to the thick, cloying stench of loss. Holmes, however, did not seem to take notice and proceeded into the room. We approached two tables standing side-by-side, the familiar shapes of cadavers atop them, covered in shrouds.

Durand drew back the white sheets which covered the bodies, and I stared at the pale corpses. Holmes circled the table and, from his inner pocket, withdrew his convex lens. Leaning over the body of Andre Dupont, he held the lens close to the wound which had been the cause of his death. Moving swiftly to the body of Madame Dupont, he did the same. In life, Michelle Dupont would have been a lovely woman. She was tall and lean, with a head of charcoal-black hair which would have cascaded down her shoulders. Despite what I knew of Dupont’s dubious past, I could not reconcile the claiming of the life of someone who I was sure was guilty of nothing.

Holmes stood and pressed the magnifying glass into my hand. “I would appreciate a doctor’s opinion,” he said. “The wounds—they were inflicted with the same weapon?”

Approaching the bodies, I held the lens close to my eye and examined the wounds in much the same manner as Holmes had just done.

“These wounds were undoubtedly inflicted by the same hand with the same weapon,” I said. “And, from the looks of it, I should think that the knife which did this was a large kitchen knife. The wounds are deep and quite wide.”

“And the hands,” Holmes continued. “Would you say that the same knife was used to sever the hands?”

I examined the bodies once more. “From what I could see, a different knife was used in this operation.”

“A different knife?” Inspector Durand echoed.

“I should imagine that the weapon was not as sharp as the one which dealt death to M. Durand and his wife. The cut is far more jagged and less clean.”

I returned the lens to Holmes who pocketed it wordlessly. He tapped his long index finger against his lips for a moment.

“Why should the murderer carry two knives on his person? What kind of butcher could have done this thing” Durand asked.

“I would be most surprised if the murderer chose to carry two weapons when one would be more than sufficient,” Holmes replied. “A kitchen knife of the type which Watson described is a formidable weapon indeed.”

“What exactly are you insinuating, M. Holmes?” Durand asked.

Holmes smiled. “At the moment, nothing. I shouldn’t wish to color your investigation more than I already have. The hour, I’m afraid, grows late, and it has been an incredibly trying day for both the Doctor and myself. First thing on the morrow, however, I must make an examination of the murder scene. That can be arranged, Inspector?”

“Oui, M. Holmes.”

“Excellent,” Sherlock Holmes replied, turning sharply on his heel. “Then, Dr. Watson and I shall bid you farewell. Or, perhaps, au revoir.”

We parted ways with the inspector in the street. Our carriage conveyed us back to our hotel where we silently made our way to our rooms. Once inside, Holmes divested himself of his coat and took up his briar pipe as he settled in before the fire.

“You are not retiring for the night?” I asked.

“No,” my friend replied. “The cogs of my brain have been set into motion and I would be doing myself a disservice should I try to halt their natural processes this night. But I am sure that you are exhausted, my dear fellow, so you needn’t wait up for me.”

I began to undo my tie as I moved towards my room. I looked forward to a good night’s sleep more than anything but, as I neared the open door, I stopped and turned around to address Holmes.

“You have begun to develop some theory, haven’t you?”

Holmes blew out a ring of smoke which encircled his head. “I have,” he replied. “If it is correct, I fear that this case may only grow ever darker.”

I roused myself early the following morning, only to find that Holmes was already awake. To my satisfaction, I saw that he was breaking his fast and, for a moment, I considered cajoling Mrs. Hudson into preparing French pastries at Baker Street if it meant that Holmes would take some sustenance more often. I joined him at the breakfast table and we exchanged pleasantries. I informed him that I had slept well, even after the grisly circumstances of the day, and was much relieved to hear that he too had made it to bed—albeit in the early hours of the morning. Holmes also informed me that he had sent an early morning telegram to rendezvous with Inspector Durand, who would convey us to the home of the late Andre Dupont.

After we had finished, we gathered our things and made our way into the hotel lobby, where we found the inspector standing at the ready for us. We exchanged a few words before we moved outside and into the awaiting cab. Though the rain had let up, the day was cloudy and foreboding. It did little to diminish the beauty of the city which, under the cover of darkness the night before, I had failed to truly appreciate. I have only been to Paris a handful of times in my life, but each time I have come away impressed by the splendor of such a lovely place.

Our carriage came to a stop on a picturesque road in the Sixth Arrondissement of the city. As we climbed out, I cast a glance up the street and saw the great tower of the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés peering over the rooftops of the nearby buildings. Inspector Durand led us through a small garden, the vegetation of which did go some way towards tucking the house away from the street. He withdrew a key from his inner pocket and inserted it into the lock of the front door. He eased it open and we stepped through.

“I have done the utmost to keep the space just as it was when the bodies were discovered, M. Holmes.”

“Your consideration is much appreciated, Inspector,” Holmes replied. “Your willingness to do so has already placed you above many of the inspectors at Scotland Yard. Now, can you show us to where the bodies were discovered?”

Durand led us through the foyer and into a well-appointed siting room. The room was small, surely not as grand as the room in which Dupont had entertained us in London, but a comfortable space nonetheless which clearly spoke to Dupont’s obvious wealth. A set of French windows opened onto a small stone veranda, though I perceived that the glass had been shattered and the drapes undulated in the light breeze which circulated through the room.

“M. Dupont was found there,” Durand indicated, pointing to a spot on the floor before the window. “His wife was found there by the settee. I have come to believe that the murderer forced his way in through the French windows and attacked M. Dupont. Madame Dupont was powerless to stop the murderer, as she was trapped in the room.”

Holmes stepped further into the room and I watched as he swiveled his head around like a great bird of prey peering through the underbrush. His piercing grey eyes scanned each opulent surface. He turned quickly and, kneeling before the window, inspected the broken pane of glass. Holmes murmured inaudibly beneath his breath as he stood and then moved to the settee on the other side of the room. I watched him consider the space—the cogs in his brain almost visible through his eyes.

“You said that the valet, Alexandre, had discovered the bodies?”

“Oui. They were discovered late in the evening. M. Dupont, according to the valet, was in the habit of taking a nightcap and, calling on his master, he found the door to the sitting room locked. When M. Dupont did not respond to his knock, the valet forced the door open.”

“And you said that there was no one else in the house at the time of the murder?”

“There was a maid, Jeanette.”

“Did she have anything to add to Alexandre’s story?”

“None whatsoever, M. Holmes,” Durand replied. “She said that she was in the kitchen at the time of the murder and heard nothing.”

Holmes tapped his lips once more in contemplation. “I’d like to see the kitchen if you don’t mind, Inspector.” He started out of the room before the officer had a chance to refuse. Durand exchanged looks with me and I shrugged my shoulders. Holmes had seemed to have lost interest entirely in the room in which the murder had taken place.

Durand drew our attention to a door at the head of a narrow staircase. Then he led us down the set of steps and into the kitchen which was furnished by an extensive series of counters.

“M. Dupont had apparently given his staff leave when he departed for London,” Durand explained. “His unanticipated return meant that the number of the household staff was greatly diminished. As I understand it, the valet and the maid were the only ones in attendance, having accompanied their master to London and back again.”

Holmes took a turn around the kitchen and, after he had performed what I could only imagine was the most cursory of examinations, turned to us and declared, “I should very much like to examine the veranda behind the house.”

“There is a second set of stairs on the opposite end of the kitchen,” Durand said, indicating the spiral staircase which sat tucked in the corner.

“Excellent,” Holmes cried. “Oh, I have forgotten my hat and stick upstairs. You gentlemen need not follow me back up. I shall return presently.”

Holmes climbed the steps and I heard him move about upstairs. He rejoined us a moment later and, insisting that we use the servant’s stairs, we made our way to the ground floor of the house and, from there, out of the house and onto the small veranda.

Holmes took a turn around the veranda and stopped before the French windows. He examined a few shards of glass and then, standing, smiled as he clapped his arms behind his back and rocked ever so slightly from his heel to his toes.

“You seem quite pleased with yourself, M. Holmes,” the inspector said.

“That is because I think that things are fitting together rather nicely,” the detective replied. “However, I think the time has finally come for us to devote attention to Monsieur Jacques Bonnaire. I would very much appreciate it, Inspector, if you did a little digging. Find out all you can about the man.”

“I shall start at once.”

“Excellent,” Holmes beamed. “As for myself, I shall take a walk. Paris is a city with which I am not too intimate and I think that a perambulation will do me some good.”

“Would you like me to accompany you, Holmes?” I asked.

“You needn’t bother, Watson,” Holmes replied. “You will find me silent company for the next few hours. Treat yourself, my dear fellow, to some of this city’s more sumptuous delicacies. I know that le petit dejeuner we had this morning will hardly be enough to satisfy your needs. Let us meet again in three hours’ time at police headquarters. Shall be that sufficient for you, Inspector?”

Durand assured Holmes that it would be and we set off in separate directions. I figured that if Holmes was willing to lose himself in the city, then I should try to do the same. I walked aimlessly for some time until I came across a pleasant café. I stopped and enjoyed a cup of café au lait and a baguette which was quite to my liking. Wandering a bit farther afield, I soon decided that it was time for me to return to more familiar environs and, flagging down a cab, was conveyed back to our hotel.

As I sat alone in the carriage, I cast my mind back to the scene of the murder. Obviously Holmes had seen far more than either the inspector or myself, but I could in no way put my finger on what it was. What, I wondered, had he seen that helped him divine some more specific connection with the mysterious Jacques Bonnaire, whose name hung over this case like the grisly shadow of death? As usual, Holmes would not explain, and I wished that he would have shared with me his theory. He clearly saw some dark circumstances surrounding this already morose affair.

Deposited at the hotel, I spent the remainder of the afternoon in quiet contemplation and, I do confess, that I dozed off. I managed to rouse myself with time to spare and caught another carriage to the Place Louis Lèpine, home of the Paris Police Prefecture. The impressive grey stone building stared down at me as I made my way inside and, after asking for Inspector Durand, was told that I could find his office on the second floor. I ascended the staircase and walked down a corridor until I came to the inspector’s small office and found him seated behind a cluttered desk; Sherlock Holmes seated across from him in the process of lighting a cigarette.

“Good of you to join us, Watson,” Holmes said as I took a seat next to him. “Inspector Durand was just about to tell us what he has unearthed on Jacques Bonnaire.”

I took a seat next to Holmes as the inspector opened a file which sat on his desk. “To begin,” Durand said, “Bonnaire was the same age as Dupont. While Dupont was a self-made man, Bonnaire was born into his wealth. They would seem, then, to be at odds from the beginning, but from all accounts, the two were close friends.

“Bonnaire married a woman one year after Dupont married his wife. Bonnaire had two children—two girls—before the death of his wife, after only a few years of marriage. Bonnaire’s children were only six and eight years old respectively at the time of his contretemps with Andre Dupont, nearly a decade ago.

“It appears as though the details of the incident as imparted to you, M. Holmes, by Dupont were accurate. Michelle Dupont did indeed contact the police at her husband’s behest. The officer who answered the call, a man called August, has since left the force, but his report was easy enough to dig up. He says that when he arrived, Jacques Bonnaire lay on the floor of the master bedroom in a pool of blood. He clutched at his chest where he had sustained a bullet wound, his other arm at his side, minus a hand. Bonnaire was conducted immediately to a hospital. He was released after nearly two weeks and, since then, he has disappeared off of the face of the earth.”

“No contact of any kind you say? None made with his solicitors or bankers?”

“Non, M. Holmes.”

“What of his children?”

The inspector turned a page in his file. “The elder daughter severed all ties with the family and has gone to ground. I could find nothing on her whatsoever. The younger daughter—as we understand it—works at a cabaret, a well-known spot in the city called Le Chat Noir.”

Holmes leaned forward and crushed his cigarette into the ashtray perched on the edge of the inspector’s desk. “She would make a most interesting study, Inspector.”

“You wish to speak to Bonnaire’s daughter?”

“Of course,” Holmes replied rising. “The sooner the better.”

“We shall go tonight then, if it is your wish.”

Holmes beamed. “Capitol, Inspector!” My friend clicked open his watch. “Ah, how the time has flown. I confess I find myself rather taken with your Parisian cuisine—and judging from the crumbs which Dr. Watson has yet to remove from his lapels, I should imagine that he is too. I think you should dine with us, Inspector. We shall think no more of M. Bonnaire for the time being. I like to think that I am well-up on Continental crime, but I cannot pass up an opportunity to discuss it with someone first-hand. I leave the choice of restaurant to you.”

True to his words, Holmes refused to speak about the case for some time. Instead, we soon found ourselves seated before a sumptuous multi-course feast at an expensive Parisian restaurant. Holmes and the inspector discussed aspects of various cases which, I do confess, left me completely lost. I wondered if Holmes was purposefully distracting himself from the matter at hand. Perhaps, I reasoned as I drained a glass of fine wine, he knew all too well the trials which lay ahead of us in the unraveling of this case. This matter had already taken a toll on my friend. In his mind, he had failed his responsibility and now he was doing all in his power to bring the criminal to book, no matter how arduous the task might prove to be. I wondered just how close to the truth he actually was.

Night had descended when we quit the restaurant. The rain had continued to hold off and, still deep in conversation, Holmes insisted that we walk the rest of the way. Our perambulation was not a long way and we drew up outside of a very inauspicious-looking building. Stepping inside, I was at once struck by the loudness of the music and the cheers from the crowd. The room was wide and open, a stage situated at the furthermost end. Men and woman of all shapes, sizes, and apparent statuses were distributed at tables throughout the room, from which they looked at the stage, currently occupied by a group of women performing a dance which, I would imagine in London, would have raised a decent number of eyebrows. Holmes, of course, took no notice and pressed on further into the room.

We took an empty table which was tucked away in the back of the barroom. The inspector and I followed Holmes’s example as he sat, and in short order we were approached by a waiter. The detective ordered us a bottle of wine in perfect French.

“Well, Holmes,” I said trying to be heard in the loud room, “what exactly do you intend to do?”

Holmes smiled mischievously and put a long finger to his lips as the waiter returned to our table.

“Parlez-vous anglais?” Holmes asked the waiter.

Our man nodded politely. “Oui, monsieur,” he replied.

“Excellent,” Holmes said. He stood and drew up a chair from a nearby unoccupied table. “Then I invite you to join us for a glass of this most excellent wine.”

A confused look crossed the waiter’s face and I am sure he was about to protest. However, Holmes all but forced the young man into the chair and had poured him a glass. Once the waiter had tentatively lifted the glass to his lips, the detective sat back in his chair.

“What is your name?”

“Henri, monsieur,” the waiter replied. “Is there something I can do for you gentlemen?”

“I rather think that there is,” Holmes replied. “My friends and I would like to speak with someone—one of the dancers, I believe. She would be about sixteen, I should imagine. Her surname is Bonnaire. Does she sound familiar?”

Before the waiter had an opportunity to answer, a big man, dressed in a garish waistcoat, sauntered up to the table. He was middle-aged, with a head of orange hair peeping out from under the brim of a battered billycock hat. He held in between his large fingers a chewed-upon cigar. He addressed the waiter sternly in French before turning to us, cocking an eyebrow.

“I am the manager of this club, messieurs. Henri tells me that you want some kind of information?”

“We’re looking for a young woman named Bonnaire,” Holmes replied. “If you could help us find her, it would be much appreciated.”

Holmes coyly removed a coin from his inner pocket and slid it along the table. The glint caught the man’s eye immediately and he picked it up, stowing it away as though he feared immediate robbery.

“I know precisely of whom you speak,” the manager replied.

“We would like to speak with her at once,” Holmes said. “It is imperative that we do so this evening.”

“I shall take you to her,” the manager replied, standing.

Holmes cast the inspector and I a beaming grin as the manager led us through the labyrinth of tables and chairs. Moving past the patrons of the club, we made our way to a small door which communicated with the backstage. The dimly-lit, private portions of the theater was alive with energy as dancers rushed hither and thither, and stagehands worked to lift and lower curtains and drops. I caught sight of Holmes casting a glance over the theatrical mechanisms before we were urged along by our guide.

“The mademoiselle you seek has not used the name Bonnaire in some time,” the manager said, “but there are few girls working here who are quite so young.”

I felt a sudden feeling of reprehension for the man. Having seen the risqué nature of some of the routines performed in this place, I couldn’t imagine a mere adolescent being involved.

We came to a door which, I concluded, led into the ladies’ dressing room. The manager addressed one of the dancers about to enter and, after she disappeared, he informed us that she would fetch the young lady we sought. The dancer was true to her word and emerged from the dressing room a moment later with a petite girl in tow. She was young—Holmes’s estimation of about sixteen or seventeen seemed most accurate—but she had quite a pretty countenance which, enhanced with the elaborate makeup utilized in the cabaret, did give the girl something of a salacious appearance. She looked at the three of us and arched an eyebrow. Holmes asked if the girl spoke English, to which she nodded.

“Mademoiselle,” Holmes began, “my name is Sherlock Holmes. This is friend and associate Dr. John Watson, and this is Inspector Erique Durand of the Paris Police Prefecture. You are the daughter of Jacques Bonnaire, are you not?”

The girl drew in a deep breath. “That is not a name I have heard in almost a decade, sir.”

“Mademoiselle,” Holmes continued, “we have reason to believe that your father is very much alive and responsible for the murder of Andre Dupont and his wife. It is most important that we speak to you at once.”

Her eyes darted around the crowded backstage area. “Allow me a few moments, gentlemen,” she said softly. She darted back into the dressing room and emerged again a moment later, a cloak draped about her shoulders. She then led us out of the building and into a narrow alleyway behind the theater.

“I apologize for the quality of the space,” she said, “but we can speak privately here. I come here to think and, I do confess, my father is often in my thoughts.”

“Naturally,” I said, laying a reassuring hand on the girl’s shoulder. “What is your name?”

“Emma,” the girl replied. “Though, most of the girls around here just call me Em. No one has called me Mademoiselle Bonnaire in quite some time. You say that my father is implicated in the murder of M. Dupont?”

“That is correct, Mademoiselle,” Durand said. “You have not heard from your father recently, have you?”

“Non,” Emma Bonnaire replied. “I do not think that I would want to after what happened.”

“Perhaps,” Holmes said, “you ought to explain.”

“My father and my sister were the only things in my world after my mother died,” Emma said. “We were a close-knit family. My father was kind, decent man. However, he—like so many—took to drink as a way to cope with the death of his wife. He soon could only take solace in the bottom of a bottle and, in his fits, he was quite uncontrollable. He was a big man, gentleman. And strong. Once, I found him seated alone in our sitting room, clutching an empty bottle. He saw me and flew into a rage and grabbed me by the arm. He very nearly pulled my arm from its socket.

“I was too young to notice it, but I suppose my father was rather keen on Madame Dupont. She was a handsome lady, I will admit and, in one of his drunken rages, I can only imagine what went through his mind, but I cannot defend what M. Dupont did, gentlemen. It was wrong and . . . savage. I never thought that a man could stoop so low. It was not simply enough to shoot my father, but he went and cut off his hand too.”

Emma Bonnaire held back a choked sob. I proffered my handkerchief, which she accepted as she dabbed at her eyes. “Merci, monsieur le Docteur.

“I can recall visiting my father in the hospital with my sister,” she continued after a moment. “He was barely conscious and in a great deal of pain. I could read the look of disgust on my sister’s face. She felt not pity for the prostrate figure laid out before her, but anger—an anger that he would attempt to seduce another man’s wife and get caught in circumstances such as these.

“I suppose it came as little surprise to me then that she ran away shortly thereafter. It was one of the hardest things I have ever had to experience in my short life. It was made all the worse when, after I learned that my father had been released from the hospital, he did nothing to reclaim me. I was subsequently entrusted into the care of an orphanage, where I remained for some considerable time. I would often lie awake at night, simply contemplating my loneliness, gentlemen. That was until I decided to strike out on my own and join this cabaret. It has served as a home for me. Hardly an ideal one, but a shelter—and a family—nonetheless.”

My heart simply broke for young Emma Bonnaire, and I laid another reassuring hand on her shoulder. She cast a glance up at me and her eyes looked like shattered mirrors. She pressed the handkerchief back into my hand and drew in another deep breath.

“Mademoiselle Bonnaire,” Holmes said at length, “while you may not have heard from your sister or your father, can you think of anything unusual happening to you within the past few weeks?”

“I can think of nothing,” she replied, “aside from, perhaps, the man who loiters outside the theater. But I cannot imagine how that could have any connection to this.”

“Humor me if you please, mademoiselle,” Holmes continued. “Who is this man?”

“I have never seen him clearly,” Emma Bonnaire replied, “but he has become something of a legend amongst the girls. One of my friends, another dancer named Suzette, said that one night after a show she was exiting the theater through this very door and was making her up the alleyway when she heard someone moving about behind her. She turned and saw the outline of a man standing just over there.”

Emma Bonnaire pointed to a spot beyond Holmes and the inspector at the foot of a small set of steps, leading down into the alleyway.

“Suzette said that she could not quite make out his face, but he appeared to be an old man. He was hunched over and seemed to have some difficulty in breathing. It was quiet night, Suzette said, and she heard his raspy breath as he leaned on the staircase railing. Suzette was about to go and ask him if he needed help, but she said that fear overtook her. You gentlemen have certainly heard tales of defenseless women in alleyways in the early hours of the morning. With that nightmare scenario running through her head, Suzette turned sharply and ran out of the alleyway.

“The next day, she told us about him and cautioned us to be on our guard. We heard and saw nothing of the mysterious man in the days which followed. However, one Friday evening a few weeks ago, a few of the girls and I decided to celebrate the end of the week. We all left together and were making our way of the theater when we caught sight of him, standing at the head of the alleyway. He was a tall, gangly-looking man dressed in a shabby, oversized coat. His hair was long and tumbled about his shoulders. And his beard was lengthy and dirty-looking as well. So shocked were we by his sudden materialization at the end of the alley that we all turned and raced back inside the theater.

“Since that day, gentlemen, we have heard nothing from the man. We have taken him to simply be one of the less fortunate who is forced to seek refuge on the streets. I very much fear that our minds ran away with ourselves and made a demon out of him.”

The faintest ghost of a smile seemed to play upon Holmes’s usually cruel, thin lips. “Mademoiselle Bonnaire,” he said, “I cannot thank you enough for your invaluable assistance.”

From his pocket, the detective withdrew a few francs and pressed them into the girl’s hand. “If these can be of any help to you, mademoiselle, please take them.”

Then turning to us, he added, “Come gentlemen, I very much suspect that—despite the lateness of the hour—the night is still young for us.”

We bade Emma Bonnaire farewell and walked to the end of the alleyway and into the street.

“Well, M. Holmes,” Inspector Durand said, “what do you intend to do next?”

“Part ways for the time being. I should very much like it if you could supply me with a city map, Inspector. If you could annotate it, as well, showing any spots in the city where you know there to be a large population without home or shelter, I would find it of great assistance. Let us all meet then once more at our hotel in an hours’ time?”

Extending his arm, Holmes hailed a cab and I clambered inside after him, leaving Inspector Durand on the street with a look of stupefaction etched on his face.

Once we were within the cab, Holmes turned to me, and solemnly asked: “You did remember to bring your service revolver?”

“Of that you can certain,” I replied.

“Excellent. I very much suspect that we shall be in need of it tonight.”

True to his word, Inspector Durand met with us again at our hotel. He produced a valise, in which he carried a map of Paris. He spread out on the dining table.

“In an attempt to answer your question, M. Holmes,” Durand said, “I consulted with a few of my fellow officers. They all agreed that here is the place where most of the city’s poor some to congregate.”

He pointed to a spot on the map along the River Seine. “The place is something of a colony,” Durand replied. “They live along the river and under bridges.”

“Excellent,” Holmes said. “Then that is where we are headed now.”

Holmes moved to the door and pulled on his hat and coat. “It has begun to rain, so take proper precautions. Now, come along.”

Silently we made our way outside and into a tumultuous deluge. It was quite a feat in tracking down a cab, and I fear that I was soaked to the skin by the time that we three sat ensconced in the relative warmth and comfort of a carriage.

Chilled from the wet, as well as the anticipation and suspense in which I was being kept, I very nearly exploded once we found ourselves rattling through the deluge.

“What are we doing, Holmes? I am used to your characteristically dramatic behavior, but this is beginning to be a bit much.”

Holmes replied in his usual, cool tone. “We are going to confront Jacques Bonnaire.”

A shiver ran up and down my spine—a chill which I cannot fully attribute to the rain which had seeped into my clothing.

In short order, our carriage eased to a halt. Holmes gestured for Inspector Durand to lead the way and, alighting, we rushed out of the carriage, seeking shelter beneath the inspector’s umbrella. We stood on a bridge overlooking both the River Seine, as well as a stone walkway below which ran parallel to the river. Durand informed us that the most likely place for us to find the homeless community was directly under the bridge. Locating a set of stone steps, Holmes pressed on undeterred.

In the darkness and rain which lashed at me, I lost sight of Holmes. I followed close at the inspector’s heels, but it felt as if we were headed into some black void. The waters of the Seine looking indistinguishable from the inky darkness which surrounded us. Standing, disoriented and shivering in the pouring rain, it was something of a godsend when I felt myself bump into my friend. He pressed a finger to his lips and, from the folds of his coat, withdrew a bulls-eye lantern. I sheltered my friend’s hands from the rain as he struck a match, letting the single point of yellow light pierce through the night.

“Now, follow me, gentlemen,” Holmes whispered, “and, pray, keep silent. If he thinks that we are searching for him, then I’m afraid that the bird shall fly the coop.”

We turned together as a small herd under the bridge and into the darkness, the pinpoint of light acting as our guide. I perceived, even in the dark, what appeared to be outlines of people shuffling in the night. Just as we had suspected, we were soon surrounded by an assortment of the city’s beggars and vagabonds. I have witnessed much strife in my lifetime, but I felt additional pity to see such a concentration of sorrowful beings.

As we moved on, passing knots of people sprawled out on the cold stone, sleeping huddled under makeshift blankets or wrapped in their tattered coats, Holmes stopped suddenly and shone the lamplight on a tall, rail-thin specimen who lay before us. Even in the dark, I could make out something familiar about the man. Though I had never clapped eyes on him, I knew at once that this must be the mysterious apparition who seemed to haunt Le Chat Noir.

The creature was some kind of nightmarish vision. He was a tall, gangly-looking man, almost to the point of emaciation. His gaunt face was shrouded, however, by an unruly, unkempt beard, and a mangy, tousled head of long hair cascaded about his face. He was clad in a shapeless brown overcoat, done over in patches and stitched back together as though someone had tried to save it from the precipice of death itself.

Holmes whispered two, haunting words: “Jacques Bonnaire.”

Movement came to the man’s limbs and he opened one, bloodshot eye, wincing in the light.

“Qui tu es?” I heard the man rasp against the wind and rain. Despite my limited knowledge of the French language, I knew that the man was asking us who we were.

“My name will mean nothing to you,” Holmes replied, “but this is Inspector Durand of the Paris Police Prefecture, and we have come to arrest you for the murder of M. Andre Dupont and his wife.”

It is beyond my skills as a writer to attempt to describe the look of savagery which crossed the man’s face at these words. In an instant, the pity for the poor soul who lay before us melted away as he transformed into some uncontrollable beast. I watched, helpless with horror, as he dug into his inner pocket and withdrew a long knife. I caught a glimpse of his shirtsleeve dangling about where his one hand once resided. With what I can only imagine was all of the man’s limited strength, he hauled himself up from the ground and attempted an escape. So startled were we by the sudden convulsion which had overcome Bonnaire that Holmes, the inspector, and I completely failed to stop him. Time seemed to slow to a crawl before Holmes cried out, “Quickly! Cut him off on the other side!”

I took to my heels and returned the way we had come, soon finding myself sprinting along the stone causeway which ran along the river. The rain had made the stones into something as slippery as ice, and I almost lost my footing on several occasions. I could barely make out the scene which transpired beneath the bridge, but with little else place to go, I stood my ground and pulled the hammer back on my revolver. I aimed, not hesitating to shoot at whatever leapt out at from the darkness.

I heard the sound of Holmes’s voice calling through the night, and I momentarily lowered my gun for fear that I might strike my friend on accident. No sooner had I done so then the figure of Jacques Bonnaire flew out at me from the void. His face contorted into some satanic visage, he screamed like a banshee as the knife flashed in the air, and I let out a gasp as its point caught my coat sleeve. I felt the cold steel against my flesh, followed by a moment of intense, searing pain, as though I’d been struck by a red hot poker. I dropped my gun and pressed a hand to my wound. The man seemed to have lost interest in me entirely, however, for he turned and started to run along the way I just come. I saw him raise the knife high over his head once again, in search of either Holmes or Durand.

In one swift movement, I had gathered up the gun from the ground and squeezed the trigger. The explosion sounded tremendous in the relative quiet of the early morning. The bullet met its mark in the back of Jacques Bonnaire, and I watched as he tumbled to the ground, his weapon falling from his hand.

A second later, I felt a hand on my shoulder and, looking up, I found myself staring at Holmes.

“Tell me that you are not hurt, Watson!” he cried.

He shined the light over me. I caught sight of a gash running along my forearm, but I was numb to the pain. The terror which had surged through my body had let to go of me.

“Jacques Bonnaire,” I said breathlessly, “is dead.”

That was the last I recall before total darkness overwhelmed me.

When I came to, I was seated upright in my bed in the hotel. Sherlock Holmes and Inspector Durand sat on two chairs at the foot, keeping vigil. I smiled as I came to and made to reach for my watch, only to find that my arm had been wrapped in a sling.

“It’s barely five in the morning, Watson,” Sherlock Holmes said.

“I haven’t felt this bad since the war,” I joked. My jest drew a smile from both men.

“Your wound was a superficial one,” Durand said. “M. Holmes insisted that we get it dressed, and our physician at the prefecture concurred that we have it attended to . . . as you can see.”

“A bloodletting was worth it, I should think,” I said, “if we were able to stop Jacques Bonnaire and bring an end to this business.”

“I rather think not,” Holmes replied darkly.

At these words, the inspector and I both turned to face Holmes, our mouths agape.

“M. Holmes, what are you talking about? Jacques Bonnaire attacked both you and Dr. Watson in his attempt to flee from the police. He was carrying a knife which, I am told, matched the type which was used to sever the hands of M. Dupont and his wife. Are you insinuating that he was innocent all along?”

“Nothing of the kind, Inspector,” Holmes replied, crossing one leg over the other. “In fact, it was Jacques Bonnaire who did sever the hands of the deceased. But it was not Bonnaire who killed M. Dupont and his wife.”

“Well then, who is guilty?” I sputtered.

“Bonnaire’s elder daughter,” Holmes replied. “You, Inspector, will know her better as Jeanette the maid.”

“Mon Dieu,” Durand said. “M. Holmes, I think you ought to explain yourself.”

“Gladly,” the detective said, as he lit a cigarette. “From the outset of this business, I thought that there was more to the case. M. Dupont showed me two letters which were making threats against his life. The second of these was postmarked London, which meant that whoever sent it had to have been in the city and returned just as quickly when Dupont and his wife decided to flee. Now, ask yourself one question, Inspector: Would Jacques Bonnaire—a man who is minus one hand and who has been inflicted with a near fatal bullet wound—be capable of crossing the channel as quickly as he did in his condition? What’s more, you and I both saw how destitute he was. The man was living on the streets, and would surely have been unable to pay the fare for two consecutive trips, let alone one.

“Knowing that there was a conspirator involved in this affair was only made all the more plausible when I was struck by the presence of two different knife wounds upon the bodies. You yourself asked the question, Inspector: Why should the murderer carry two different knives when one would be more than efficient? The simplest answer is that there was more than one murderer involved. And, this became even more likely after an examination of the scene. You will doubtlessly recall that I took a moment to analyze a few shards of glass which I found on the veranda. You assumed that that glass was left after the murderer gained forceful entry into the house. If that had been the case, Inspector, the glass would have been found on the inside of the room and not outside. That window was broken after the murders were committed.

“And, lastly, you told me, Inspector, that the maid, Jeanette, was in the kitchen and heard nothing on the night of the murder. Perhaps you would be so good as to cast your minds back to the afternoon we examined the scene. I returned to the room to fetch my hat and stick—”

“And I clearly heard you moving about upstairs,” I interjected.

“As I figured that you would,” Holmes replied. “Jeanette would have to have been lying when she said that she could not hear anything transpiring upstairs. The design of the house and the kitchen would have placed her almost directly underneath of the room in which her employers were killed. The weapon itself is also connected with the kitchen. It would not be too difficult a task to search the kitchen for the knife, Inspector. And, if you find one, feel free to send it my way. I have developed something of a test which will differentiate blood from a whole host of other substances. Its presence on a blade should not be too difficult a thing to ascertain, given a few hours of concentration.

“As I see it, Jeannette—if her name truly is Jeannette—felt not repulsion for her father when she saw him lying, dying in a hospital bed all those years ago, but a yearning for revenge against the man who had done this. Her disappearance gave her ample opportunity to begin seeking employment in some of the wealthiest houses in France, bringing her into the social circle of M. Andre Dupont. After some years, I rather think that Dupont would fail to recognize the little girl who had once been the daughter of his friend, and he hired Jeannette, completely unaware of the conspiracy against him. Jeannette was working with her father to avenge him and began the persecution, creating fear in the Dupont household. Even when he attempted to flee, she would follow. Dupont told us that he brought only his most trusted staff to England, and you confirmed, Inspector, that Jeannette was in London.

“On the night of the murder, Jeannette aided her father’s entry into the house. She stabbed to death both M. Dupont and his wife before her father began his bloody task. Once she had managed his escape, Jeannette broke the window to convincingly approximate a break-in—inadvertently casting suspicion solely on her father—and then returned to the kitchen. I am glad only that the police investigation has run this long, Inspector. Should Jeannette have tried to flee before now, surely she would have been easily traced. However, I suggest that you apprehend her as soon as possible. News of the action by the river shall spread fast and, with nothing else to lose, I fear that she might do anything in so desperate a situation.”

Durand rose from his chair. “I shall put my best men to it immediately.”

“Excellent,” Holmes replied. The two shook hands. “It has been an absolute pleasure working alongside you on two separate occasions and, should the needs arise, please feel free to contact me again.”

“I shall do so only too happily,” Durand replied. “I shall see myself off. Au revoir, gentlemen.”

I found myself feeling in much better sorts during the remainder of the day, and the following morning, Holmes and I found ourselves once more trundling across the French countryside by train. Holmes had remained silent about the case but, as he sat, casting a glance out of the yet again rain-streaked windows, I noticed a certain melancholia descend upon him.

“You have vindicated yourself,” I said trying to coax him from his brown study. “You have seen justice served once again.”

“You are right, Watson,” Holmes replied, “but one cannot go unaffected by what we have witnessed here these past few days. This adventure of the Parisian Butcher has only reinforced to me what a bleak world we inhabit.”

“Well,” I said, “it should then reinforce what a role you must play in it, then. If the world is as bleak and dark as you make it out to be, then surely the world needs a Sherlock Holmes to maintain the light.”