ON THE CORNER OF Whitehall Place and Whitehall Court is the memorial to the Royal Tank Regiment, which is a tribute to all those who have served in tanks since they were first used in 1916. The monument consists of five crewmen from a Second World War tank, and the regimental badges are set into the base. Along the front of the sculpture is the phrase ‘From mud through blood to the green fields beyond’, which is attributed to Brigadier General Elles, who led the tanks into battle at Cambrai in 1917; the words reflect the colours of the regimental flag: brown, red and green. The memorial was sculpted by Vivien Mallock, and is based on a design by George Henry Paulin. The memorial was unveiled by the Queen, the Regiment’s Colonel-in-Chief, in 2000.

The Royal Tank Regiment memorial in Whitehall Place.

In Horse Guards Avenue is the Gurkha Memorial, which remembers the many years of faithful service the Gurkha regiments have given, fighting alongside the British Army in many theatres of war. The 9-foot bronze statue of a Gurkha in First World War uniform was sculpted by Philip Jackson, and is based on a sculpture by Richard Goulden erected in India in 1924. It was unveiled in 1997 by the Queen, accompanied by the Duke of Edinburgh and Prince Charles, Colonel-in-Chief of the Royal Gurkha Rifles. A plaque lists the battles of the two world wars in which they fought, and carved into the plinth, beneath a pair of crossed Gurkha knives, or khukuris, are words of tribute from Sir Ralph Turner: ‘Bravest of the brave, most generous of the generous, never had country more faithful friends than you.’

The Gurkha Memorial in Horse Guards Avenue.

In the middle of Whitehall, appropriately opposite the old War Office, is the bronze equestrian statue of Prince George, 2nd Duke of Cambridge (1819–1904), grandson of George III. He fought in the Crimea, and from 1856 to 1895 was Commander-in-Chief of the Army. The statue is by Adrian Jones, and stands on a granite plinth designed by John Belcher. The Duke is depicted in the uniform of a Field Marshal, with the many medals and Orders he was granted. At the front and back of the plinth are bas reliefs of soldiers from the 17th Lancers and the Grenadier Guards, regiments in which the Duke served. The statue was unveiled in 1905 by Edward VII.

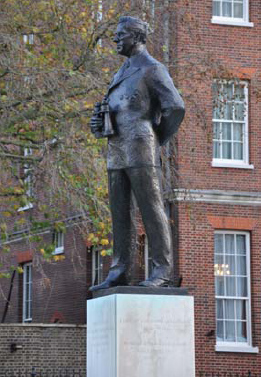

At the Whitehall end of Horse Guards Avenue is a statue of the 8th Duke of Devonshire (1833–1908), a politician of some importance but little renown. The memorial stands close to the old War Office, where he was Secretary of State for War. He is best known for having sent Gordon to the Sudan and failing to persuade Gladstone to send a relief expedition in time to rescue him. For a time he was leader of the Liberal Party, and turned down the chance to become prime minister on three occasions. The statue is by Herbert Hampton, and it was unveiled in 1911. On the back of the plinth is the family coat of arms with its motto Cavendo tutus (‘safety through caution’), which seems to be an appropriate comment on his political career.

The Duke of Cambridge was Commander-in-Chief of the Army for nearly forty years.

The Duke of Devonshire turned down the chance of being prime minister three times.

Above the entrance to the Banqueting House is a bust of Charles I (1600–49) by an unknown sculptor and dating from around 1800. It is one of three busts of the king found in a Fulham builder’s yard in 1945 by Hedley Hope-Nicholson, who was the Secretary of the Society of King Charles the Martyr. It was through a window of the Banqueting House that the king stepped to his execution on 30 January 1649, and every year on the anniversary of the event wreaths are placed on the railings.

In the middle of Whitehall opposite the Banqueting House is the equestrian statue of Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig (1861–1928). Haig fought in the Boer War and served in India before becoming Commander-in-Chief of the British Forces during the First World War. His tactics eventually won the war, but he was much criticised for his refusal to change a strategy which led to the massive loss of human lives. The statue raised to him was to prove as controversial as his career. There was a limited competition for the statue, and designs were presented by William McMillan, Gilbert Ledward and Alfred Frank Hardiman. Hardiman was given the commission, but his first model was much criticised, especially by Lady Haig, because the horse looked nothing like Haig’s horse, Poperinghe, and Haig’s posture was incorrect. There were letters of complaint to The Times from, among others, Robert Baden-Powell and A. J. Munnings, an artist famous for his paintings of horses. Hardiman stated that he had produced a ‘symbolic horse, not a realistic one’, but he agreed to produce a second model, this time accepted by Parliament, which was paying for the memorial. However, even this version did not please Haig’s widow, who found the cloak too theatrical and later complained that he should be wearing a hat with his uniform. Hardiman had, in fact, compromised, and the head of Haig was now highly realistic, while the horse was clearly inspired by his study of Renaissance sculpture. The memorial was unveiled on 10 November 1937 by the Duke of Gloucester, but Lady Haig, rather pointedly, did not attend the ceremony. The following day, Armistice Day, the king laid a wreath at the statue.

This bust of Charles I is close to the spot where he was executed in 1649.

The equestrian statue of Earl Haig was highly controversial when it was erected.

In front of the Ministry of Defence is Raleigh Green, named after the statue of Sir Walter Raleigh which stood here until 2001, when it was moved to Greenwich (see page 198). The space is now occupied by the statues of three Second World War heroes. On the left is the statue of William Joseph Slim, 1st Viscount Slim (1891–1970). He fought at Gallipoli in the First World War, where he was badly wounded, and was awarded the Military Cross for his service in Mesopotamia. He was known as a great strategist, and during the Second World War, as commander of the Fourteenth Army, he led a highly successful, if often unconventional, campaign to recapture Burma from the Japanese. In 1948 he succeeded Montgomery as Chief of the Imperial General Staff and from 1952–9 was Governor-General of Australia. The statue is by Ivor Roberts-Jones and was unveiled in 1990 by the Queen.

Viscount Slim’s statue on Raleigh Green in Whitehall.

In the centre is the statue of Alan Francis Brooke, 1st Viscount Alanbrooke (1883–1963). He came from a family with a long military tradition and distinguished himself in the First World War. During the Second World War he played an important part in the evacuation from Dunkirk, and was later chief adviser on strategy to the War Cabinet. Although he and Churchill never got on, the combination of Alanbrooke’s clear, quick brain and eye for detail, and Churchill’s energy and drive, made for a hugely successful partnership. After the war he retired in favour of Montgomery, and spent more time on his favourite hobby of ornithology. The statue, by Ivor Roberts-Jones, was unveiled by the Queen in 1994.

Ivor Roberts-Jones’s statue of Viscount Alanbrooke.

‘Monty’ in a typical pose and wearing his favourite beret.

The third of the statues is of Viscount Montgomery of Alamein (1887–1976). Montgomery was considered to be Britain’s finest military leader since the Duke of Wellington, and he was responsible for some of the finest victories in the Second World War. He is probably best remembered for his triumph against Rommel at El Alamein, which was one of the most important victories of the war, but his leadership of the D-day Landings was probably an even greater achievement. Montgomery was ruthless, vain and arrogant, but he was also a brilliant teacher, and an inspirational leader who cared greatly for the men under his command, who revered him. The statue, by the Croatian sculptor, Oscar Nemon, was unveiled in 1980 by Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. It shows him in battledress and wearing his familiar beret. Above his full name and title, and in larger letters, is the name he was generally known by, Monty.

This unusual memorial remembers the part played by women in the Second World War.

In the middle of Whitehall, opposite Raleigh Green, is the memorial to The Women of World War II. The 22-foot bronze sculpture is the work of John Mills, and commemorates the important role played by over seven million women during the war, in many different roles. Hanging on pegs on all four sides are the uniforms and work clothes they wore, both in the armed forces and in factories and hospitals. The memorial was unveiled in 2005 by the Queen, who had herself, as a young princess, joined the Auxiliary Territorial Service and taken a course in vehicle maintenance during the war.

At the bottom end of Whitehall is the Cenotaph, which commemorates all those who have died in the two world wars and all wars in which British troops have fought since. The word ‘cenotaph’ derives from two Greek words meaning ‘empty tomb’. The original memorial, designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, was of timber and plaster, and took only a week to design and build. It was created for the Peace Day parade in July 1919, and it caused such a strong impression that the Cabinet decided almost immediately that it should be replaced by a permanent version in stone. There were safety concerns about it being sited in such a busy thoroughfare, and locations such as The Mall and Parliament Square were put forward as alternatives, but these were soon cast aside because of the memories the Whitehall site already inspired. On the first anniversary of Armistice Day later that year, Whitehall was packed with dignitaries and ordinary people, many carrying wreaths or bunches of flowers to place at the base of the Cenotaph, and the first two-minute silence was observed. The new stone Cenotaph was unveiled by George V on 11 November 1920, when the coffin of the Unknown Warrior stood in front of it before being taken to Westminster Abbey to be buried. The moving Remembrance Day service is still carried out today, with the sovereign, politicians and veterans laying wreaths to remember the fallen in all wars. The Cenotaph is a simple and dignified memorial, built of Portland stone, and it carries no religious symbolism. There are carved wreaths at each end and on the tomb-shaped top of the memorial, and on each side are flags of the British Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force. At one end are carved the words ‘The Glorious Dead’, chosen by Rudyard Kipling, who lost his own son in the First World War. There are replicas of Lutyens’s Cenotaph in Canada, New Zealand, Australia and Hong Kong.

The Cenotaph in November, after the annual Remembrance Day ceremonies.

Clive of India had to wait 133 years for his national memorial.

At the end of King Charles Street, overlooking St James’s Park, is the statue of Robert Clive, 1st Baron Clive of Plassey (1725–74). Clive first went to India at the age of seventeen to work as a clerk with the East India Company, and spent most of his working life there, as a successful military officer and administrator. When he retired to England he had to defend himself against accusations of profiteering from his position. Although a controversial figure, he had been instrumental in developing a British empire in India, and he had to wait a long time for a national memorial. In 1907 Lord Curzon invited subscriptions for a statue and soon had enough money to select a sculptor and get permission to erect it at a location very close to the India Office, at the top of the steps due to be built down to St James’s Park from King Charles Street. The chosen sculptor was John Tweed, and the statue was ready in 1912, but it had to be placed temporarily in the garden of Gwydyr House in Whitehall until 1917, when work on the steps was completed. Clive wears the military uniform of the period, complete with a sword hanging from his belt. Around the plinth are three reliefs depicting significant scenes from his life: the siege of Arcot, the eve of the battle of Plassey, and Clive receiving the Grant of Bengal.

At the bottom of Clive Steps is the Bali Memorial, which remembers the victims of the terrorist bombings in Bali in 2002. It was unveiled by the Prince of Wales and the Duchess of Cornwall on the fourth anniversary of the attack. It consists of a granite globe carved with 202 different doves, representing each individual who died, including twenty-eight Britons, as well as people from twenty other countries. Behind is a Portland stone wall with the names and ages of the victims carved into it. The simple and moving memorial is the work of artist Gary Breeze and sculptor Martin Cook.

The Bali Memorial commemorates the victims of the terrorist bombing in 2002.

On Foreign Office Green, on the south side of Horse Guards Parade and facing the Admiralty, is a statue of Earl Mountbatten of Burma (1900–79). Mountbatten, or Dickie as he was known to his friends, was born Prince Louis of Battenberg, with close connections to the British and German royal families. He joined the Navy as a teenager and in the inter-war years rose through the ranks. His exploits as a wartime captain were immortalised in the film In Which we Serve, starring Noël Coward. After the war he was made the last Viceroy of India, responsible for the handover of British power. He was killed by an IRA bomb in Ireland. The statue, by Franta Belsky, a Czech-born sculptor, was unveiled by the Queen in 1983. He is shown in the uniform of Admiral of the Fleet.

Earl Mountbatten on Foreign Office Green.

On the south side of Horse Guards Parade is the statue of Horatio Herbert Kitchener, Earl Kitchener of Khartoum (1850–1916), appropriately close to memorials to Roberts and Wolseley. He first came to prominence on Wolseley’s unsuccessful expedition to save Gordon in Khartoum, and increased his reputation in the Boer War as Roberts’s deputy. During the Second World War he was Secretary of State for War, but in 1916 he died when the ship he was taking to negotiate with the Russians hit a German mine and sank off the Orkneys. He is probably best known today for the famous ‘Your Country Needs You’ recruiting poster. A controversial figure, he nevertheless became a popular hero, despite being disliked in many quarters; Margot Asquith once called him ‘a great poster but not a great man’. His statue is by John Tweed, and was unveiled in 1926 by the Prince of Wales.

Nearby is the Cádiz Memorial, a French mortar resting on the back of a splendid Chinese dragon. The mortar was presented to the Prince Regent by the Spanish Government to commemorate the raising of the siege of Cádiz in 1812 by the Duke of Wellington. On the front are the Prince of Wales feathers. It was soon nicknamed ‘The Regent’s Bomb’ (pronounced ‘bum’), and there were many cartoons by George Cruickshank and others using it for their political satire, including one image where the Prince Regent is himself the mortar.

Kitchener is today best known for a famous recruiting poster.

The Cádiz Memorial, also known as ‘The Regent’s Bomb’.

On either side of the main gateway are equestrian statues of two military rivals. To the right is the statue of Frederick Sleigh Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts (1832–1914). He won the Victoria Cross in the Indian Mutiny, fought in the Afghan War, and was in command of the troops in the Boer War. In 1900 he succeeded Wolseley as Commander-in-Chief of the British Army and received the Order of the Garter. He was known as ‘Bobs’, and Kipling wrote an affectionate poem about him of that name. He was an excellent horseman, and the statue shows him riding his favourite horse, a grey Arab called Volonel. It is one of the liveliest depictions of a horse in London. The memorial is a reduced replica of the original by Harry Bates, which was erected in Calcutta in 1898, a year before the sculptor’s death. There is another, full-size, copy in Glasgow, but for the London version, made by Bates’s assistant, Henry Poole, the plinth is lower and lacks the symbolic sculpture, as the memorial had to be scaled down to match the size of the Wolseley statue. It was unveiled in 1924 by the Duke of Connaught.

Earl Roberts’s horse is one of the most spirited in London.

Wolseley was the original of the ‘Modern Major-General’ in The Pirates of Penzance.

The equestrian statue to the left of the archway is that of Garnet Joseph Wolseley, 1st Viscount Wolseley (1833–1913). Wolseley’s family could not afford to buy him a commission, but he rapidly rose through the ranks on ability alone. He saw action in Burma, India and the Crimea, where he met Gordon, and he later led the ill-fated expedition to relieve Gordon in Khartoum. In 1894 he became Commander-in-Chief of the British Army. He was famous for his efficiency, and the phrase ‘All Sir Garnet’ came to mean that everything was in order. He was also the inspiration for Major-General Stanley, the ‘Modern Major-General’ in Gilbert and Sullivan’s Pirates of Penzance. Wolseley never took offence at this and would often sing the song at family gatherings. The statue is by Sir William Goscombe John, and was cast from guns captured during Wolseley’s campaigns. It was originally intended to stand in Trafalgar Square, replacing either Napier or George IV, but in the end Horse Guards Parade was felt to be more appropriate. Wolseley is shown in full Field Marshal’s uniform, the choice of Lady Wolseley (others had wanted him to be depicted wearing regular combat gear). The statue was unveiled in 1920 by the Duke of Connaught.

On the north side of the parade ground is the Royal Naval Division Memorial, which remembers the 45,000 men of the RND who died in the First World War. The Division was formed by the First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill, in 1914 and was disbanded in 1919. The memorial was designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, and unveiled by Winston Churchill in 1925 on the tenth anniversary of the landings at Gallipoli. It takes the form of an obelisk in a fountain basin, with the badges of the various units around the rim of the plinth. On one side is carved a stanza from the poem 1914 III: The Dead by Rupert Brooke, who died in 1915 on active service with the RND. The memorial originally stood on this site, but in 1939 it was taken down to make way for the Citadel and reerected in 1951 at Greenwich. It returned here in 2003, when Greenwich ceased to be a naval establishment, and it was rededicated by the Prince of Wales.

The Royal Naval Division Memorial spent over sixty years in Greenwich.

Facing Horse Guards on the western side is the Guards Division Memorial, commemorating soldiers of the Guards regiments who lost their lives in the two world wars. It is a most apposite location for the memorial, as Horse Guards is the parade ground for the Guards regiments, who take part in Trooping the Colour here every year. The memorial was designed by the architect Harold Chalton Bradshaw and the sculptor Gilbert Ledward, and is in the form of a cenotaph of Portland stone. The five bronze figures, cast from guns captured during the First World War, represent the Guards regiments, and were modelled on guardsmen from each of the regiments. On the back of the memorial is a very fine bas relief of a field gun in action. The inscription on the upper part of the memorial was written by Rudyard Kipling. The memorial was unveiled in 1926 by the Duke of Connaught, assisted by General Sir George Higginson, ‘Father of the Guards’, who was over a hundred years old.

Gilbert Ledward’s depiction of a field gun in action on the Guards Division Memorial.