13

FROM GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS TO GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT CHAINS

CHANGING PARADIGMS

OLIVIER CATTANEO AND SÉBASTIEN MIROUDOT

International trade is not new. Greeks and Phoenicians were already known to trade a variety of goods and services across the Mediterranean Sea in ancient times. The same can be said about international production; raw materials available in one country have always been traded to others not endowed with the same resources. Vertical specialization—that is, the unbundling of production into different stages performed in different places—was already common in thirteenth-century England with “cottage workers” (Jones and Kierzkowski 2005).

What is new is first and foremost the scale of the phenomenon. As noted by Baldwin (2006, 2012), there was a first “unbundling” in the second half of the nineteenth century (1850–1914) and from the 1960s onward, corresponding to the separation of production and consumption. Trade liberalization and technological advances have reduced trade costs to such an extent that most goods (and an increasing number of services) produced in one country can be shipped to others for final consumption without being at a price disadvantage. Concentrating production in one location is cost-efficient because of scale economies, and low trade costs ensure that goods can be cheaply delivered despite the distance from the location of production.

In what can be described as a “second unbundling,” production itself is split among countries. Starting in the mid-1980s, more and more firms began fragmenting their production processes, taking advantage of lower costs of production and access to specific inputs and skills in different countries. The second unbundling is explained both by the reduction in trade costs and by lower “coordination” or “transaction” costs. Organizing production in a global value chain involving several countries is costly because intermediate goods and services have to be moved across space but also because activities performed in different places have to be coordinated. This coordination is expensive, but technological advances (e.g., the internet) and progress in management methods have reduced the cost in the past three decades, enabling firms to increase the fragmentation of production. By splitting production among several locations, firms pay more for “services links” and coordination activities but can still benefit from location-specific advantages (knowledge assets, skills, and technological spillovers, as well as lower labor costs).

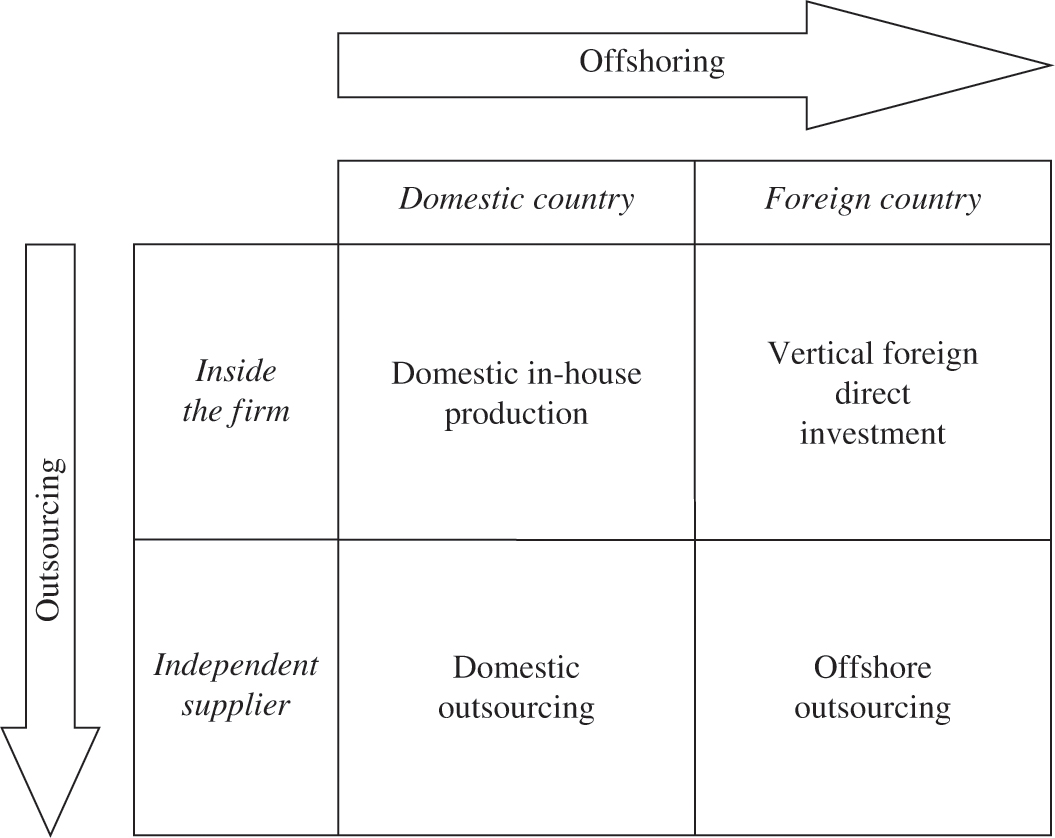

There are two dimensions to the second unbundling. Production activities are geographically and organizationally separated, through offshoring (moving some stages of production abroad) and outsourcing (the strategy of firms to focus on their core competencies and have independent suppliers carry out activities that were previously performed in-house). Offshoring describes the relocation of activities across countries while outsourcing is the redefinition of firms’ boundaries. As figure 13-1 shows, firms that retain in-house production do not have a strategy of offshoring or outsourcing. Firms that move some stages of production abroad but keep the activity within the firm are conducting vertical foreign direct investment (a form of offshoring), while firms that use independent suppliers to provide the product are performing offshore outsourcing (or just domestic outsourcing if the supplier remains domestic). Vertical FDI creates intrafirm trade while offshore outsourcing leads to vertical arm’s-length trade. Vertical trade (between affiliated companies or at arm’s length) explains most of the growth in world trade (Yi 2003). While difficult to measure, intrafirm trade has also increased in recent decades (Lanz and Miroudot 2011).

FIGURE 13-1. New Sourcing Strategies

Source: Antràs and Helpman (2004).

What the recent literature on “firm heterogeneity” highlights is that different types of firms make different choices and co-exist in the same market (Bernard and others 2007). Firms start to export when their productivity reaches a certain cutoff level (Melitz 2003), and the most productive tend to vertically integrate (Antràs and Helpman 2004). The least productive firms exit the market, and there is thus an intra-industry reallocation of resources. Above the productivity cutoff, several types of firms with different outsourcing and offshoring strategies co-exist. Multinational enterprises are not the only users of global production networks; there are also firms without any foreign affiliates that participate in global value chains, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).

Analysis of Global Value Chains

A value chain includes the full range of activities that firms undertake, starting from the conception of a product to its end use by consumers (Gereffi and Fernandez-Stark 2016). These activities, such as design, production, marketing, and support, are increasingly spread over different countries and have reshaped international trade.

As explained by Bair (2005), the origin of the analysis of global value chains can be traced back to the 1970s when the concept of a “commodity chain” was introduced by Hopkins and Wallerstein (1977). The idea was to trace all the sets of inputs and transformations that lead to an “ultimate consumable” and to describe a linked set of processes that culminate in this item. The concept of a “global commodity chain” was later introduced in the work of Gereffi (1994). Figure 13-2 shows the example of the apparel commodity chain, from the raw materials (such as cotton, wool, or synthetic fibers) to the final products (garments).

In the 2000s, there was a shift in terminology from the “global commodity chain” to the “global value chain,” the latter coming from the analysis of trade and industrial organization as a value-added chain in the international business literature (Porter 1985). The concept of a value chain is not hugely different from that of the commodity chain, but it is more ambitious in the sense that it tries to capture the determinants of the organization of global industries (Bair 2005). Gereffi, Humphrey, and Sturgeon (2005) provide a theoretical framework for the value chain analysis and describe five types of global value chain governance: market, modular, relational, captive, and hierarchy.

A third and more recent strand of research emphasizes the concept of “network” rather than “chain” (Coe and Hess 2007). This change in the metaphor highlights the complexity of the interactions among global producers: “Economic processes must be conceptualized in terms of a complex circuitry with a multiplicity of linkages and feedback loops rather than just ‘simple’ circuits or, even worse, linear flows” (Hudson 2004, 462).

The analysis of global value chains is therefore a relatively new field at the crossroads of business, sociology, and economic research. In the area of trade, the global value chain (GVC) approach builds on the concepts of “production sharing” (Yeats 1997), “international fragmentation” (Jones and Kierzkowski 2001), “vertical specialization” (Hummels, Ishii, and Yi 2001), “global sourcing” (Antràs and Helpman 2004), “second unbundling” (Baldwin 2006), and “trade in tasks” (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg 2008). This literature has shed light on the motivations of firms to offshore and fragment production processes, as well as the gains expected from the international division of labor.

FIGURE 13-2. The Apparel Commodity Chain

Source: Gereffi (1994); Appelbaum and Gereffi (2004).

Twenty-first Century or Back to the Past?

In discussions of the impact of global value chains on trade theory and trade policy, there are always skeptics who say that the global value chain is merely a repackaging of things that trade economists have known for a long time. To some extent, this is true: the fragmentation of production has always existed, and it piqued the interest of some analysts before the beginning of the “second unbundling” in the 1980s.

For example, intra-industry trade was the focus of Grubel and Lloyd’s (1975) attempt to explain international trade with differentiated products. But one should also recall that initially intra-industry trade was regarded as a statistical artifact (Jones and Kierzkowski 2005). To explain intra-industry trade in intermediate inputs, the theory of “trade in middle products” was proposed by Sanyal and Jones (1982). With respect to investment, Agmon (1979) was already asking whether foreign direct investment (FDI) and intra-industry trade were substitutes or complements. Finally, input-output analysis, which is at the heart of new empirical work on the measurement of trade in value-added terms (OECD and WTO 2012), comes from the work of Leontief, who was already considering multiregional flows (Leontief and Strout 1963).

One can even look further in the past to Ohlin (1933). To echo Paul Krugman (1982), who asked whether all was in Ohlin, Ohlin made the case for the fragmentation of production and the role of firms in international trade. Ohlin wrote, for example, that “production is in many cases divided not into two stages—raw materials and finished goods—but into many.” In addition, he provided a theory on the location of activities: “The localisation of producers’ buying markets (e.g., the manufacturing of paper) … depends upon the localisation of consumers’ markets for the finished products and upon the localisation of ‘half material’ production (pulp).” One can even find the concept of firm heterogeneity in his work: “It should be noted also that a commodity may be produced by several different processes, and that the best location for a firm using one of them may be different from that for firms using another.” The following excerpt is also very close to the conclusions that can be found in the empirical work of Bernard and others (2007) and the theoretical work of Melitz (2003): “International trade is between firms, not between nations. Certain firms export while others do not; some export only to a few special foreign markets, others to a number of them. Some firms are able to hold a part of the home market against foreign competition, others succumb.”

Needed: A New Paradigm for Trade and Development Policies

Turning to the economic development challenge: What are the implications of the observed changes in international trade and production for the potential role of trade in economic development? How did governments adjust their trade and development policies to these new global business practices?

In their reviews of fifty years of trade and development policies, Krueger (1997) and Winters (2000) observed a number of changes, including the radical move from an “import substitution” model to an “outer-oriented” trade regime. Table 13-1 summarizes these policy trends and evolutions. In the 1950s, it was thought that import substitution would lead to industrialization, and domestic markets were protected to allow infant industries to reach a critical stage of development before being exposed to competition. In practice, however, an alternative strategy based on promoting trade, rather than curtailing it, proved more successful with the early success (in the 1960s) of the so-called Asian tigers. At the same time, some analytical efforts were made to evidence the negative side effects of import substitution strategies, including arbitrariness, poor specialization choices, economic distortions, and rents. With a view to achieving higher growth rates, some countries chose to open their economies and remove selected trade barriers. Outward orientation became the prevailing trade regime, although the debate still rages today, in particular after the 2008 global economic crisis stressed the risks associated with the increasing interdependence of world economies (Haddad and Shepherd 2011).

Trade-focused development policies have changed accordingly. Import substitution policies justified the introduction of “special and differential treatment” in favor of developing countries, including the authorization to adopt unilateral trade preferences (i.e., tariffs below the most favored nation rate): developing countries could have preferential access to developed countries’ markets or, put differently, they could maintain higher tariffs than their richer counterparts. These unilateral preferences, in turn, were criticized, in particular when they were associated with strict rules of origin or disparate conditions that created discrimination among developing countries, or confined developing countries to the production of low-value-added goods. These criticisms, combined with the progressive erosion of preferences that resulted from the successful lowering of average tariffs on most goods, led to the replacement of unilateral trade preferences by reciprocal trade preferences (e.g., in the context of regional trade and partnership agreements) and the creation of a form of aid dedicated to trade adjustment and capacity building. The launch of the so-called Aid for Trade Initiative in 2005, led by the World Trade Organization (WTO), aimed to enable developing countries to benefit from further trade liberalization in partner countries by building their capacity to trade: indeed, market access is not sufficient to create new export opportunities if the country lacks basic infrastructure, production capacities, human resources, transport and logistics, telecommunications, and other functions that it needs to be competitive, respond to international demand, and participate in global trade flows.

TABLE 13-1. A Stylized History of Postwar Thinking on Trade Policy as Development Policy, 1950s–1990s

|

Decade |

Macro policy |

Resource allocation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1950s |

Import substitution • Commodity pessimism and industrialization • Infant economy protection • Special and differential treatment • Regionalism |

Welfare economics of trade • Second best |

||

|

1960s and 1970s |

Export promotion |

General theory of distortions • Infant industry arguments Costs of protection Effective protection |

||

|

1980s |

Outward orientation • Getting prices right • Fallacy of composition • Costs of adjustment |

Political economy of protection • Rent seeking |

||

|

1990s |

Endogenous growth • Theory and evidence • Governance Economic geography |

Trade and technology Poverty/income distribution |

||

|

Source: Winters (2000). |

||||

Thus trade and development policies have evolved over time. The move to reciprocity and aid for trade (AFT) has put more emphasis on trade capacities than on market access and traditional barriers to trade. As such, it paves the way for further adaptation of trade and development policies to the reality of trade and business strategies: building capacities not only helps domestic firms become more competitive and better linked to global markets; it also makes the country more attractive to foreign investors and international business in search of input providers and opportunities to delocalize production and services.

At the same time, in practice, AFT often seems to be more of the same for the same, reflecting old aid and trade policy paradigms. First, it appears that the bulk of AFT is old aid repackaged. A meta-evaluation of AFT projects has thus revealed that objectives assigned to AFT projects are often only remotely—if at all—related to trade (OECD 2011; Messerlin and others 2011). This is typically the case for infrastructure projects that once were excluded from AFT accounts.

Second, benefactors of old preferences often became AFT recipients. For example, a number of projects have targeted the textile industry that faced the phasing out of quotas under the Multi-Fiber Agreement, which was in effect from 1974 to 2004. This could be interpreted either as a success of AFT as an adjustment tool, or a vector of the prolongation of existing rents.

Third, one could argue that aid unilateralism has replaced preference unilateralism. The geography of bilateral AFT still reflects old preferences. In addition, donors have continued to promote access to selected products in their own markets—in the spirit of unilateral preferences—rather than access to third markets. For example, a number of AFT projects have promoted standards and rules (e.g., for geographical indications and for patents) that are country- or region-specific: this has prolonged the dependence of developing countries on traditional markets and hindered diversification efforts. The shift in demand from OECD to emerging markets could challenge this strategy, resulting in a lower return on investment in standards.

Fourth, one can ask whether policies moved from picking the winners of import substitution to picking the winners of outward orientation. Export promotion strategies sometimes have the flavor of industrial policies, picking sectors with a high export potential and replicating success stories. There is thus a vast economic literature on export discovery and survival.

In sum, the appearance of change hides an important inertia in trade and development policies that widens the gap between the reality of trade and business strategies and policy interventions aimed at facilitating developing countries’ participation in global trade. The following section suggests a new fundamental change in trade and development policies to fill this gap and further improve the effectiveness of AFT and trade and development strategies more generally.

Preliminary Reflections on the Concept of Global Development Chains

The need for a new trade and development policy paradigm has become more obvious since the economic crisis of 2008–2009, which accelerated preexisting trends in international trade, such as the shift in demand from the OECD countries to emerging markets and the consolidation of global value chains. A number of state intervention mechanisms have been challenged: developed countries could not massively resort to protectionism as they did in the 1930s owing to existing regional and international trade commitments (i.e., rules contained in plurilateral and multilateral trade agreements, such as the WTO) and an increased dependence on backward and forward links within GVCs; developing countries became collateral damage of a crisis born in the collapse of the US housing and subprime mortgage markets through their participation in GVCs. Developed and developing countries appeared more interdependent than ever, and old trade policy intervention mechanisms were revealed to be obsolete. A change in paradigm is needed, both from the perspective of the developed countries to restore or increase the effectiveness of trade and development policies, and from the perspective of developing countries to fully harness the benefits of trade, aid, and other forms of transfers that foster socioeconomic upgrading.

The concept of global development chains captures those recent changes in practice. Trade and socioeconomic upgrading (or development) now take place within global value chains: pull the links apart (e.g., through the adoption of new barriers to trade) and the whole system collapses; tighten the links (e.g., through increased trade flows or capacity-building efforts) and the whole system becomes stronger. The concept of global development chains not only reinforces the idea of intertwined and interdependent economies, thereby introducing a more balanced relationship between donor and recipient countries of development aid; it also recognizes the role of the private sector in trade and development. The debt and budget crises faced by many donor countries also argue in favor of development schemes that do not fully rely on public contributions and that reconsider the respective roles of the public and private sectors in socioeconomic upgrading.

Adapting trade and development policies to the reality of business and global economic relations will require four major changes in paradigm that are captured in the concept of global development chains and are further detailed and explained in the following sections.

CHANGES IN THE RELEVANT STRATEGIC FRAMEWORK: FROM COUNTRIES TO FIRMS AND GLOBAL VALUE CHAINS

The first and most important change introduced by global value chains is the need for policies to look beyond individual countries and be global from the start. Both import substitution and export promotion strategies assume that capacity should first be developed within a given country and that only then can “home-grown” companies compete in international markets. The new paradigm of global development chains suggests that this happens first by linking global buyers with suppliers to develop capacity and that access to imports is more important than exports when trying to move up the value chain.

From Single-Country Strategies to Global Value Chains

Most of development thinking so far has focused on the development of capacity within a closed economy not yet connected to the rest of the world. The old paradigm looks like the diagram in figure 13-3. Through import substitution or some kind of industrial policy, domestic firms have to grow and become productive. Once they have the capacity to compete in international markets, efforts should be made to put in place trade facilitation and export promotion policies to sell domestic products to consumers in developed countries. This old paradigm assumes that there is a sequencing issue and that the link to world markets only happens at the end of the process, when the local industry is “ready.” Aid for trade and open markets policies are regarded only as tools to reach consumers in developed countries.

The strategies illustrated in figure 13-3 can be more or less protectionist. The infant industry argument would suggest putting prohibitive trade barriers in place to ensure that domestic consumers only buy the products of the local industry. Once nurtured by high tariffs, domestic companies can then compete internationally (when they have reached the required productivity). A more protrade liberalization version of figure 13-3 consists of letting foreign products compete with the local industry, to give enough incentives to domestic firms to increase their productivity and possibly learn from foreign competitors. But the focus of the trade agenda will be on the export side to promote domestic products and reduce trade costs with partners in the developed world.

FIGURE 13-3. The Old Paradigm

What is missing in figure 13-3 are imports of intermediate products and the fact that the “local industry” can contribute not by reproducing the full production process domestically, but rather by specializing in one stage. This will allow it to quickly become efficient using local capacities and to “upgrade” (move up the value chain to other activities) by connecting with global buyers and suppliers. The new paradigm is represented in figure 13-4. Efficient sourcing (the import side) is as important as the reduction in trade costs on the export side. World markets are not only consumers in developed countries waiting for products from the developing world; world markets provide inputs to be processed, as well as capital, services, and technology. The local capacity depends on these flows of production factors and knowledge, which are even more important with the digital transformation of economies.

FIGURE 13-4. The New Paradigm

Within the country, policies should focus on infrastructure and efficient services to ensure that the “mechanics of development” work (Lucas 1988). Figure 13-4 also emphasizes that access to consumers includes consumers in the developed world and in emerging economies. Moreover, this access is not direct. An important role is played by wholesalers and retailers because the global value chain does not end when the final product is produced. It has to be shipped, marketed, and sold in a retail network. This part of the chain is as important as the rest (including the value added that is generated), and the role of “intermediaries” in international trade is increasingly highlighted in economic research (Bernard, Grazzi, and Tomasi 2011). And once again, these important actors in international trade and production are private firms, not states.

The Length of GVCs (Domestic and Intercountry)

The new reality of business in global value chains can be illustrated by looking at input-output data and calculating indicators of the fragmentation of production. Figure 13-5 below provides an index from the input-output literature that can be understood as the “length” of GVCs. The higher the value, the higher the number of production stages involved. And the data allow a distinction between the domestic part of the value chain (involving domestic companies) and the international part (involving companies in other countries). Figure 13-5 illustrates that, in most manufacturing industries and a growing number of services industries, value chains are long and complex, and often highly internationalized.

FIGURE 13-5. The Length of Global Value Chains, Domestic and Intercountry, by Industry

Source: Authors’ calculations, based on the methodology described in Miroudot and De Backer (2013). Data are for 2015.

The “Servicification” of Manufacturing

Another empirical fact that supports the new paradigm presented on figure 13-4 is the real role of services in international trade when looking at trade on a value-added rather than a gross basis. Although international trade in services is generally regarded as accounting for only about 25 percent of total trade (Loungani and others 2017), the reality is a bit different, because most services that are traded are embodied in goods. A more accurate calculation of the share of gross exports representing value added in the services sector is that about 49 percent of world trade is services trade (Miroudot and Cadestin 2017).

Services are the “links” that permit the functioning of value chains. The logistics chain involves transportation services, communication services, storage, and packaging services. Trade has to be financed, and goods and people insured, so there are important financial services involved. Moving and training people relies on a variety of social services. Business services cover a broad range of consulting, accounting, and advertising services needed by firms. An empirical study conducted by the Swedish National Board of Trade identifies about forty different types of services that are involved when a manufacturing firm internationalizes its production (figure 13-6). These services are also key for development and for the insertion of developing countries in GVCs.

In addition, manufacturing firms increasingly sell and export services to their customers. By becoming service providers, these firms add value, create loyalty, and generate a more stable income flow along the product life cycle. This phenomenon, described as the “servicification of manufacturing” in the business and management literature (Vandermerwe and Rada 1988), blurs the lines between goods and services and implies that developing countries do not have to choose between goods and services in their exports. They need both to participate in global value chains.

From the Old to the New Paradigm: Policy Implications

It should be recognized that both trade and development policies have long been entrenched at countries’ borders: traditional trade policy instruments are applied by customs authorities, and traditional development aid is dispensed at the country level, according to Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) and other studies that are country-focused. As early as the 1960s, trade policies started to adjust and negotiations targeted “beyond-the-border” obstacles to trade: a series of plurilateral “codes” were adopted during the Tokyo Round of multilateral trade negotiations (1974–1979), and the Uruguay Round (1986–1994) extended the scope of the negotiations to include more disciplines on beyond-the-border regulations—for example, in the domain of services. The Doha Development Agenda that was launched in 2001 for the first time included truly cross-border disciplines, such as trade facilitation (e.g., freedom of transit). Progress in development policies has been slower, although the development of Regional Economic Communities (RECs) introduced new perspectives for regional aid coordination and projects.

FIGURE 13-6. The “Servicification” of Manufacturing

Source: Swedish National Board of Trade (2010).

The Aid for Trade Initiative helped shift the focus from obstacles at the border and market access to beyond-the-border obstacles and capacity constraints. However, the move from supply to demand-driven trade and development strategies has not been fully achieved: in the same way that industrial policies aimed to pick national champions that would ultimately become exporters, AFT projects often pick sectors with high export potential (on the basis of success stories in countries with similar endowments or levels of development) and supplement capacity building with export promotion efforts. After trying to remedy market failures affecting export discoveries, governments then measure their success and review the key determinants of export survival.

Within GVCs, imports are just as important as exports; a country cannot become a major exporter unless it first becomes a major importer and is well connected to world markets both upstream and downstream in its production. Participation in GVCs secures the demand for certain goods and services and is a key determinant of export survival. Discovery and diversification can also take place in GVCs depending on the type of GVC and the lead firm. As a result, instead of focusing on export promotion, trade and development policies should focus on encouraging foreign direct investment (FDI), fixing the domestic business environment, and removing obstacles to imports. In addition to building capacities and infrastructure, AFT can promote trade facilitation, transport, and logistics.

For example, in the food sector, an old-type supply-driven AFT project could consist in developing green bean production in an African country, replicating successful experiences in comparable countries, and hoping for the same success. A new-type demand-driven policy would facilitate the establishment of international retailers: those retailers would first import products that meet their standards until local producers could upgrade and meet those same standards. Then the retailer would source most of its products locally and eventually select a few products that have a high potential for export and distribute them in other countries where the retailer is already established (see Mattoo and Payton, 2007 for the example of ShopRite in Zambia). The same model can be applied to international manufacturers, with a first phase of establishment and production for the local market, and a second phase of exporting products with high potential to places where the manufacturer distributes its products. In both cases, only the private sector bears the cost of discovery and runs the risk of export survival.

Until recently, socioeconomic development and upgrading had been discussed in the context of old-type trade and development strategies based on import substitution and export orientation (Fold and Larsen 2008). With the emergence of global production in many sectors, upgrading has been increasingly linked to GVCs (Kaplinsky and Morris 2001). This helped shift the focus from the country to the firm level. For example, Humphrey and Schmitz (2002) proposed an influential fourfold upgrading classification:

- functional upgrading, whereby an improvement in the position of firms would result from increasing the range of functions performed and moving from lower-value activities with high competition (e.g., manufacturing) into higher-value activities (e.g., design, branding, marketing, and logistics);

- process upgrading, which yields efficiency gains by reorganizing the production system and introducing new technologies;

- product upgrading, with higher unit value prices as products become more sophisticated;

- interchain upgrading, with capabilities that were acquired in one chain leading to competitive benefits in another.

Upgrading also includes social and development dimensions, since the positioning on higher-value activities could result in an increase in the value of trade captured by the country, and could be associated with the diffusion of higher standards, safer and greener production methods, and knowledge-intensive activities. However, it appears that upgrading opportunities vary with the core competencies of the lead firm (e.g., buyer-led versus retailer-led GVC; see Gereffi 1994, 1999; Bair and Gereffi 2001) and the type of network structure: captive, relational, or modular (Gereffi, Humphrey, and Sturgeon 2005). In turn, different types of policy measures are needed to accompany upgrading efforts and prevent noncompetitive practices within GVCs. Figure 13-7 shows how the maturity of GVCs is linked with their development content: not all GVCs have the potential to become global development chains. Some lead firms tap into the resources of poorer countries without transferring any knowledge or technology or offering real upgrading prospects. Three phases of development are distinguished: a predation phase in which developing countries are limited to the exportation of raw materials and importation of processed goods and services; a segmentation phase in which developing countries benefit from the delocalization of certain production activities, mostly to serve local markets; and a consolidation phase in which local innovation leads to the export of processed goods and services to other developing and developed countries. While the last phase has the highest development content, it is also more selective: the consolidation of GVCs corresponds to a diminution in the number of participants in GVCs, and hence threatens to leave more developing countries outside major trade flows and upgrading paths.

FIGURE 13-7. Three Phases of Development in the Global Value Chain

FIGURE 13-8. China’s Imports of Gabonese Logs and Selected Wood Products, 1970–2007 (thousand cubic meters)

Source: Kaplinsky, Terheggen, and Tijaja (2010), based on ForeSTAT data.

Staritz, Gereffi, and Cattaneo (2011) have also analyzed changes in upgrading prospects within GVCs when end markets shift to the South. In line with the theory of maturation of GVCs presented in figure 13-7, lead firms and end markets shape the development path of upstream participating countries. Figure 13-8 shows the example of the timber value chain between Gabon in China: between 1985 and 1995, China’s imports of processed wood (plywood) grew steadily, until China could acquire the technology to build its own transformation industries; thereafter, China mostly imported logs (unprocessed wood), causing the crisis of the transformation industry in Gabon. Chinese lead firms in this industry are thus in a predation phase. Kaplinsky, Terheggen, and Tijaja (2010) show that Chinese importers are mostly interested in quantities and price, paying little attention to labor standards and sustainable harvesting. Thus, socioeconomic upgrading is limited in this phase, corresponding instead to a loss in capacities and downgrading.

CHANGES IN THE RELEVANT ECONOMIC FRAMEWORK: FROM INDUSTRIES TO TASKS AND BUSINESS FUNCTIONS

The second change necessitated by the introduction of global value chains is related to the relevant unit of analysis. Most development strategies are presented as “industrial policies” by which the state sponsors the birth of new industries. Economists discuss whether the initial growth of such industries should be sheltered from foreign competition or, instead, oriented toward exports and international markets. From our point of view, the main mistake is not in thinking that governments can effectively identify and promote successful industries, but in already assuming that new industries should be created to compete with existing value chains. Today, the specialization of countries is not in industries but in specific tasks and activities in the value chain—what the management literature has described as “business functions.” There is a functional specialization in trade that makes what countries do more important than what they export (Timmer, Miroudot, and de Vries 2019). Industries already exist, and new entrants on international markets should find their place in the network of suppliers of inputs and final goods and services producers. They are very unlikely to recreate domestically complex supply chains that are now split among countries to maximize productivity.

FROM INDUSTRIES TO TASKS AND BUSINESS FUNCTIONS: WHAT “SLICING UP” THE VALUE CHAIN MEANS

The value chain analysis starts with the identification of steps in the production process, steps that can be performed in-house or that can be offshored and outsourced. Porter (1985) was among the first to propose a decomposition of the value chain according to different types of activities (figure 13-9). Primary activities include inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and some after-sale services. These primary activities are supported by more horizontal corporate activities: firm infrastructure, human resources management, technology development, and procurement.

The (international) fragmentation of production first took place among the primary activities. Assembly and manufacturing were outsourced and offshored, most often to nearby countries. More recently, as international trade and transaction costs have declined, more services activities, such as human resources, research and development, and customer service are outsourced or offshored to more remote countries (emerging economies).

What is important to understand from figure 13-9 is that “business functions” are offshored or outsourced, not firms or industries. The fragmentation of production is within the value chain. If a single firm is in charge of all activities and some of those activities are offshored or outsourced, this firm still exists in the domestic economy and there is specialization in specific parts of the production process. The outcome is very different from competition between two producers, where one gains market share and the other may “disappear.”

FIGURE 13-9. The Value Chain: Outsourcing and Offshoring

Source: Porter (1985); OECD (2011). Boxes indicate the outsourced and offshored activities.

An encouraging corollary is that developing economies do not have to build capacity in all business functions before exporting. Becoming part of a value chain implies a specialization in only one step of the production process. The entry cost is thus lower than with import-substitution strategies; joining a GVC is faster and easier (Baldwin 2012).

The trade literature has also introduced a smaller unit of specialization based on specific workers’ activities: the tasks they perform. When tasks are outsourced their offshoring becomes “trade in tasks” (Grossman and Rossi-Hansberg 2006). Some evidence on changes in the task intensity of output can be found, but as emphasized by Lanz, Miroudot, and Nordås (2012), there is no clear evidence that the fragmentation of production goes to the task level. Firms generally prefer “multitasked” workers: “Toyotism” rather than “Fordism” remains the dominant production model.

FIGURE 13-10. Upgrading within Value Chains

The important point is that production isn’t treated as if it happens inside a “black box” but is analyzed as consisting of four layers (Baldwin and Evenett 2012): tasks, occupations, stages, and products. It is at the level of “stages” that most of the unbundling and internationalization of production takes place. And this explains why globalization is seen as more “granular” in the context of GVCs.

New Upgrading and Development Paths

The shift from industry to tasks allows the definition of far more precise development strategies. Socioeconomic development is not only about moving from low- to high-value-added sectors—for example, from agriculture to manufacturing and services; it is about identifying, within each sector, high-value-added activities to specialize in (figure 13-10). Specialization according to comparative advantage takes place within GVCs, and the competitiveness of the whole chain depends on the best repartition of tasks within the chain. Thus GVCs offer a new path for diversification that is more incremental than stochastic discoveries.

FIGURE 13-11. Value-Adding Activities in the Apparel Global Value Chain

Source: Adapted from Frederick (2010).

In turn, the upgrading and diversification dynamics that take place in GVCs could play against the further segmentation of global production. Indeed, the most recent trend is toward the consolidation of GVCs—the bundling of tasks along GVCs to limit the number of partners involved. For example, going forward, a country that is currently specialized in apparel production might not be able to remain part of major GVCs unless it also develops a capacity to offer design, logistics, marketing, and other services to the lead firm. Those countries able to upgrade and diversify their tasks will remain in the chain, and others will be excluded. Thus it is not enough to build capacity in only one segment of the production chain, and countries should adopt development strategies that promote task bundling in a context of GVC consolidation. It is not about reverting to industry-level strategies, but bundling tasks at key levels of the production chain to increase the local value added (figure 13-11).

CHANGES IN THE RELEVANT ECONOMIC ASSETS: FROM ENDOWMENTS AND STOCKS TO FLOWS

As emphasized by Henderson and others (2002), “In order to understand the dynamics of development in a given place … we must comprehend how places are being transformed by flows of capital, labor, knowledge, power, etc.” The idea that flows matter more than stocks and endowments was quite a shift, given that trade theory still largely viewed capital and labor endowments as the source of comparative advantage. According to the new thinking, policies should focus on how to link to global production networks and attract flows of capital, labor, and knowledge, implying that policies should look beyond borders and traditional actors such as states.

Flows Are More Important Than Stocks and Endowments

In an open economy, productivity does not depend only on local factors of production. The economics literature has identified several links between international flows of capital, labor, and knowledge (including data) and the productivity in a given location. First, in the world of GVCs, production factors are not immobile. Capital moves easily from one location to another. Recent theories emphasize that capital does not go where it is scarce and consequently more remunerated, but that another driving force is the export specialization of the economy in capital-intensive sectors (Jin 2012). This explains why capital flows more often to advanced economies than it does to developing countries—a paradox first identified by Lucas (1990). This link between export specialization and capital flows is important for understanding how productivity and local capacity are developed through connections to global value chains. With respect to labor, despite important restrictions on the movement of people, there is evidence that the migration of high-skill workers has a positive impact on productivity (see, e.g., Grossman and Stadelmann 2012). In the context of GVCs, people often move as “intracorporate transferees,” and there are fewer barriers to this temporary movement of persons.

Second, technology can be traded and imported (Keller 2004). R&D flows can be seen as “services” or “intangible assets” and directly improve the productivity of domestic firms. Technology can also be directly transferred through foreign direct investment when foreign companies create affiliates and transfer their technology internally. Movements of people also carry the know-how and technology of workers who share their knowledge with domestic firms. Last, technology is embodied in foreign inputs. Trade in intermediate inputs can explain international links that are key to growth and development (Jones 2011).

In addition, there are technological spillovers or indirect transfers of technology. The literature emphasizes forward and backward links when firms are engaged in vertical trade or vertical FDI (Havranek and Irsova 2011). Companies increase their productivity by using foreign inputs, but contacts with customers and buyers are also important. Their feedback and help to improve products and services also increase productivity. Last, procompetitive effects from foreign firms and foreign products also stimulate productivity growth in the domestic economy.

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to review all the literature on the productivity impact of international flows of capital, labor, and knowledge. There are sometimes mixed results, and the experience may be different from one country to another, depending on its “absorptive capacity.” But there are two important conclusions from this literature. First, productivity does not increase when producers are isolated from the rest of the world. An important source of productivity growth is through the connectedness with the rest of the world, and even more the digitalization of economies. Second, the interaction between different types of flows matters. As illustrated with capital flows, they cannot be understood if one does not look at international trade. Similarly, FDI spillovers are higher when trade is liberalized (a result from the meta-analysis carried out by Havranek and Irsova 2011). Flows matter more than endowments and stocks, but the combination of different flows is the driver of productivity gains.

Global Development Chains in Action

As we have already noted, upgrading and development prospects that accompany flows and transfers of all kinds within GVCs may vary with the origin, nature, and maturity of the lead firm. In the three-phase typology of figure 13-7, at the predation phase, knowledge and technology transfers from the lead firm to subcontractors are almost nonexistent; they increase progressively, along with capacity-building efforts, with the maturity of the GVC and its lead firm. Once a certain level of maturity is reached, GVCs become a major channel of transfers of all kinds, with the potential to remedy initial capacity issues. Thus, through GVCs, the private sector has become a major contributor to trade capacity building in developing countries, along with the public sector through the AFT Initiative.

In 2011, the World Bank analyzed those global development chains in action by collecting case stories relating international business’s contribution to trade capacity-building efforts in developing countries (World Bank 2011). Those efforts were classified in four categories:

1. Human Capacity Building

The transmission of knowledge within GVCs is important, whether the lead company is established abroad or just sources out some activities to foreign contractors. Insofar as the workforce is deficient in specific skills needed, foreign companies often establish training programs. While benefiting the company in the short run, such programs can contribute to sustainable long-term benefits for the recipients who can apply their newly acquired skills in numerous ways, resulting in positive spillover effects for the country (e.g., alumni of multinational corporations often count among the most successful local entrepreneurs and exporters). For example, over 2.4 million Chinese farmers participated in the Cargill rural development program that aims to enhance local farmers’ productivity.

2. Productive Capacity Bolstering

The efficiency of each link in the GVC affects the competitiveness of the whole chain and its lead firm. With a view to reducing operating costs and improving business operation all along the value chain, multinational corporations proceed to transfer technology, know-how, capital, and other assets to local affiliates and contractors. For example, GE opened a technology and innovation center in India, which exports goods and services worth over US$1 billion. Syngenta disseminated crop advice using mobile technology in India. Danone helped with the development of milk co-operatives in Ukraine. During the crisis, 41 percent of Kohl’s suppliers benefited from the group’s supply chain finance program.

3. Value Chain Performance Enhancement

Beyond capacity building, promoting the sustainable inclusion of small producers in global value chains is fundamental to fighting poverty. If small-scale producers can link to the chain while at the same time obtaining assistance to help with needed certification for higher-value-added production, they will be able to take much better advantage of market access opportunities. For example, Kraft Foods’ participation in the Africa cashew initiative aims to reinforce market links; the Nespresso AAA sustainable quality program aims to improve production quality standards; Dow’s safer operations and emergency preparedness program in China aims to increase safety standards; Unilever’s SustainabiliTea project aims to promote sustainable farming.

4. Trade Facilitation and Business Environment Improvement

Finally, it is important to facilitate the flows between the different links of the GVC. A number of projects pertain to trade facilitation, such as the Global Express Association’s work to improve risk assessment at customs in Latin America. Trade facilitation could also be interpreted in a broader sense to include the removal of nontrade barriers, such as the fight against road insecurity (Total’s road safety project in Africa) or corruption (Diageo’s business coalition against corruption in Cameroon).

Dynamic Effects of Global Development Chains

Transfers and capacity-building efforts that take place within GVCs have both direct and indirect or dynamic effects. While benefiting the company at the origin of the transfers, the capacity-building efforts to improve infrastructure or the business environment can be expected to have positive spillover effects on the local economy at large. It is also easier to evaluate the impact of private sector–led projects since the company aims to increase its benefits and therefore needs a return on “investment.”

Potential spillover effects are most obvious in the case of hard capacities, such as infrastructure: for example, the German Technical Cooperation Agency (GTZ) analyzed the economic, environmental, and social impact of BASF investments in the region of Nanjing, China, and observed positive spillover effects for the local population, including through the use of new transport and power facilities (Kurz and Schmidkonz 2005). Such spillover effects also exist for soft capacities, such as knowledge: for example, the partnership between the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) and Hewlett-Packard (HP) has created over 17,000 jobs and trained more than 42,000 students to convert their business plans into commercial ventures. Sometimes investment programs also include development projects not directly linked to the investment itself that benefit the local community at large: for example, Barrick launched an initiative in Argentina to help farmers in mining regions where it invested to develop a sustainable sun-dried tomato business—thereby also raising the available income of households by offering job opportunities to the wives of their mine employees (World Bank 2011). In its SAGCOT project in Tanzania, the World Economic Forum and its partners adopted a holistic approach to foreign investment, with the objective of adding 420,000 jobs and US$1.2 billion in annual farming income, and lifting 2 million out of poverty (World Bank 2011).

The evaluation of AFT has long been a challenge for the donor community (see e.g., OECD 2010). Global development chains offer new perspectives for evaluation, since private sector capacity-building efforts need to generate commercial benefits. The case stories described earlier provide good examples of impact evaluation, with precise data on the number of jobs created, income generated, productivity gains, exports, and other information. Those who do trade are best able to measure the impact of trade capacity-building efforts. Those measurements can pertain to the international business’s benefits and productivity gains, as well as the benefits to local contractors: for example, it is estimated that the PepsiCo Educampo project in Mexico led to an 80 percent increase in local farmers’ productivity and a 300 percent increase in income (World Bank 2011).

A New Role for Trade and Development Policies

Global development chains call for a new role for trade and development policies, including AFT (OECD 2012). If GVCs are a major source of trade and socioeconomic upgrading opportunities, trade and development policies can help developing countries to participate in such chains, facilitate the transfers that take place within the chains, and promote forward and backward links. Similarly, if the consolidation of GVCs represents a major risk of exclusion for some developing countries, trade and development policies can aim to maintain those countries in GVCs by helping them improve productivity through the upgrading and task development required by lead firms.

Policies aimed at facilitating transfers within GVCs will differ depending on the type of transfer, from capital to technology to knowledge. In general terms, policies should be about improving business environment and the legal and regulatory framework for investment. Trade and private sector development (PSD) policies tend to be more closely aligned when trade policies tackle beyond-the-border issues. For example, it quickly became evident during the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations that “trade-related intellectual property rights” (TRIPS) covered most aspects of intellectual property protection: in the context of GVC development, the protection of intellectual property rights is essential to technology transfers. Other aspects include competition law, investment protection, and labor law.

In addition, global development chains can become a laboratory for successful trade and development projects owing to the “obligation of result” of the private sector. Collected case stories show significant (and measured) results, somewhat limited, however, to the level of ambition of the lead firms: for example, a foreign company can only train a limited number of engineers; revealed needs can create incentives for further training and capacity building by public authorities. A better coordination of public and private efforts can help scale up successful initiatives in the private sector.

CHANGES IN THE RELEVANT BARRIERS AND IMPETUS: FROM PUBLIC TO PRIVATE

While most development thinking is state-centric, becoming part of a value chain is done by private actors. This is the fourth important change related to the emergence of global value chains. Firms, not governments, conduct international trade; firms organize the flows of capital, labor, and knowledge. The role of development policies is very different when states are no longer in charge of starting new economic activities but have to help domestic companies connect to global production networks. While governments must still ensure that they provide the right business-enabling environment, this might not be enough to reach suppliers, buyers, and consumers around the world. New types of policies have to be designed that facilitate the insertion of local actors into global networks.

Public versus Private Barriers in Access to World Markets

By moving from border to beyond-the-border barriers, trade policy has adjusted somewhat to the change in the relevant strategic framework, from countries to GVCs and firms. For example, in the area of competition law, the market of reference is not necessarily the domestic market of a single country: it could extend beyond the borders to include multiple trade partners (e.g., the European Union). Figure 13-12 shows the evolution of trade barriers over time, from the border to beyond the border, and from the public to the private sphere: private anticompetitive behaviors can affect the terms of trade as much as official quotas and taxes. Governments therefore moved into the regulation of such behaviors, creating standards, norms, and other rules that can become nontariff barriers to trade in the absence of regional or multilateral harmonization.

With the prevalence of GVCs, trade barriers have made a further step into the private sphere at the same time that they became truly borderless. For example, private standards have replaced public ones: while these standards are voluntary, lack of compliance can prevent companies from participating in GVCs. These standards might be adopted at the level of a profession, a consortium of firms, or a single lead firm—sometimes also under the umbrella of corporate social responsibility (CSR). For example, in the medical tourism sector, most countries have their own certification and accreditation rules for hospitals; however, an accreditation by the Joint Commission International (JCI) is often necessary to attract foreign patients. The Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) provides another example of the importance of private standards and certification in the food industry (see next section). ISO standards are private, although widely used and recognized, including in public administrations.

FIGURE 13-12. The Evolution of Trade Barriers

In addition, some lead firms have enough leverage not only to impose their own standards (quality, labor conditions, sustainability, and the like), but also to challenge the normal functioning of the market. Depending on the type of network structure prevailing in a GVC—captive, relational, modular—the lead could become a price maker and the developing country providers could be confined to the role of price takers (Gereffi, Humphrey, and Sturgeon 2005). A farming contract, for instance, guarantees an income for smallholder farmers in developing countries, but also limits the potential benefits from major peaks in farm commodity prices. Some vertical agreements within GVCs might therefore present challenges from a competition law perspective. Land grabbing and the capture of scarce natural resources by foreign groups also raises concerns and objections.

Promoting the Convergence of the Public and Private Agendas

Trade and development policies need, once again, to adjust to the recent trends and changes in paradigm of business practice. GVCs provide both an opportunity and a risk for development: an opportunity because of the important transfers of all kinds that take place within GVCs and capacity-building efforts that are properly evaluated and could be scaled up to foster socioeconomic upgrading and development; a risk because of the consolidation phenomenon that threatens to reverse the process of worldwide division of labor, the predatory attitude of some lead firms in low-maturity GVCs, and the appearance of new forms of allegiance that threaten the normal functioning of markets. In other words, there is a case both for further recognizing and encouraging the role of the private sector and GVCs in trade capacity building, and for ensuring that GVCs promote fair, balanced, equitable, and sustainable development. The first step is for development partners and the private sector to agree on common objectives and the means to achieve them.

The G-20’s Action Plan on Food Price Volatility and Agriculture, released in 2011, is a good illustration of the possible convergence of public and private agendas. The collection of over fifty case stories on private sector trade capacity-building efforts in the food and agriculture sector set the scene for the private sector in action. Fairly quickly, the negotiations over the G-20 Action Plan developed a number of consensual principles, objectives, and priorities for action among the participants, which included international organizations, a CEO task force, and G-20 members. Their final recommendations revealed a high degree of convergence.

The final consensus reached by the G-20, the international organizations and the private sector should inspire future actions and partnerships in other sectors. In a number of places, the Action Plan calls for explicit public-private partnerships. For instance, the Action Plan encourages multilateral and regional development banks to continue supporting country-owned development strategies and further strengthen their engagement with the private sector. From its inception, the Action Plan was conceived as a multistakeholder initiative on topics ranging from increasing production and productivity to promoting sustainable sourcing and production, improving business environments, strengthening markets and supply chains, and improving food safety and risk management.

Preventing Abuses of Dominant Positions within GVCs

The ability of public and private sectors to agree on common objectives and priorities for action should not minimize the difficulty of the task and the diversity of incentives and goals among lead firms and GVCs. The main objective of private firms remains profit, whereas the main driver of public actions should be the public good. Thus relationships within GVCs can be unbalanced and not always in the interests of the developing countries if, for instance, a lead firm abuses its dominant position. GVCs can be the scene of emergence of new barriers to trade that are more difficult to identify and remove.

Vertical agreements and anticompetitive behaviors within GVCs are frequent, and not all countries have sophisticated enough competition laws or enforcement mechanisms to monitor or remedy them. Similarly, lack of transparency in procurement rules can be unfair to small business. With regard to investment, a number of initiatives were launched to agree on “responsible investment principles.” For example, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is a coalition of governments, companies, civil society groups, investors, and international organizations that promotes transparency and good governance in the extraction of natural resources and the use of its revenues; in the agricultural sector, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), and the World Bank have jointly developed a set of Principles for Responsible Agricultural Investment (PRAI) that respects rights, livelihoods, and resources; and the UN Global Compact asks companies to embrace, support, and enact, within their sphere of influence, a set of core values in the areas of human rights, labor standards, the environment, and anticorruption.

Most of those initiatives are nonbinding sets of principles and recommendations (i.e., soft law). Thus the challenge of regulating new barriers to trade in GVCs remains. Paradoxically, the so-called Singapore issues (trade facilitation, competition, transparency in government procurement, and investment) that were once in the Doha Development Agenda and withdrawn (with the exception of trade facilitation) from the negotiations mandate in 2003, would have been the most relevant set of rules for dealing with new barriers to trade that are inherent in business relationships within GVCs.

A New Distribution of Public and Private Roles

Notwithstanding those risks, the potential of global development chains is important, and it appears more than ever useful to combine public and private forces to build trade capacity in developing countries. Progress could be easily made on a joint trade capacity-building agenda given the importance of already existing efforts. Some projects already coordinate or combine public and private actions. A more systematic and organized dialogue could be established with a view to:

- Sharing information about initiatives pertaining to trade capacity building. This effort would respond to the lack of awareness in governments of what the private sector is doing, and vice versa. Concretely, it would consist in the designation of contact points and regular online posting of case stories presenting initiatives undertaken jointly by the public sector, the private sector, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs).

- Fostering leadership and operational-level dialogue among public and private sector actors as well as NGOs to identify and agree on shared priorities for action. Each actor might have access to different types of information or data that would help others better identify the problems and solutions. For instance, the private sector is best positioned to identify obstacles to the efficient functioning of markets (such as trade costs). Each could also bring its experience to the table to identify best practices and success stories that could be reproduced on a larger scale. Each also has specific responsibilities (e.g., the governments to adopt trade and investment enabling rules; multinational corporations to disseminate technologies and expertise).

- Identifying opportunities for public-private-civil society collaboration to advance progress on agreed priorities, particularly to enable scaling up of effective models and leveraging of public sector funds to catalyze increased private sector investment. Projects could be joint or merely better coordinated with each other.

- Monitoring and assessing the impact of existing public and private sector or NGO trade capacity-building initiatives to share lessons and define best practices.

All these objectives should be pursued with due regard to the priorities set by the recipient country or region in its development programs. Donors, the private sector, and NGOs should cooperate with local governments and actors, in particular smaller businesses and communities, to assist with their development plans and respond to their needs. Such cooperation should not exclude the active participation and assistance of international public and private actors in the elaboration of those development plans.

Figures 13-13 and 13-14 illustrate a change in paradigm in the provision of AFT to take into account the reality of the markets and the way trade takes place within GVCs. In the first scenario, the donor supports capacity building in the certification of rubber in Cambodia: the institutional change is valuable, but the post-project evaluation underlines the questions of the producers’ capacities, the connection with international markets, and the financial sustainability of the newly created institutions (AFD 2009). This type of project is typical of the old paradigm, where AFT is supply-driven and used to raise the standards in developing countries, focused on institutional capacities, without sufficient connections with the private sector (upstream and downstream) and the markets. In the second scenario, the private sector is in the driver’s seat, with global capacity-building programs that target small and less-developed businesses (SLDBs) around the world. Once certified following the guidelines of the Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI), the products are recognized everywhere. This type of project is typical of the new paradigm, where capacity building is demand-driven, and participants in the initiative not only benefit from the capacity-building efforts made by a consortium of 650 stakeholders in seventy countries, but also get access to a market of over €2 trillion of sales (GFSI 2012). Of course, this type of project also raises questions pertaining to competition and relationships within GVCs, as noted earlier, but it is an example of coordination and results-oriented trade capacity-building efforts that could inspire other private and public interventions in developing countries.

FIGURE 13-13. Standards under the Old Aid for Trade Paradigm: Rubber Certification in Cambodia

Source: Authors, based on AFD (2009).

FIGURE 13-14. Standards under the New Paradigm of Aid for Trade: The Global Food Safety Initiative

Source: Authors, based on information from the Global Food Safety Initiative.

CONCLUSION: ADAPTING AID FOR TRADE

Globalization and the prevalence of GVCs point at new development paths. Tasks that were previously executed in developed countries can now be outsourced to developing countries, creating local jobs and value added, encouraging knowledge and technology transfers, and other advancements. The more mature GVCs have become a major channel for socioeconomic upgrading in developing countries. However, in the consolidation phase of GVCs the number of beneficiaries of transfers will shrink, and only those developing countries that are able to offer the appropriate “bundle of tasks” will remain in the game; others will be excluded from major trade flows. Moreover, relationships within GVCs might raise competition and other issues pertaining to the privatization of standards that have not yet been tackled by public policy.

It is time for trade and development policies to adjust to these new business practices to maximize the opportunities and minimize the risks associated with the successive waves of fragmentation and consolidation of global production. Maximizing the opportunities means facilitating all kinds of transfers (including capital, knowledge, and technology) from lead firms to small producers in developing countries, promoting foreign investment, and securing socioeconomic upgrades through the capture of higher-value-added segments of production. Minimizing the risks means defining the rules for responsible investment and due respect of competition within GVCs, as well as supporting adjustment to the changing needs of those who conduct trade (e.g., by diversifying tasks in order to remain in the game when global production enters the consolidation phase).

Accordingly, trade development strategies should change. Old references have become obsolete: the relevant strategic framework has shifted from countries to firms and GVCs; the relevant economic framework has shifted from industries to tasks and business functions; the relevant economic assets have become flows rather than stocks and endowments; and the relevant barriers to trade and the impetus have shifted from public to private. These changes will need to operate in a context that is particularly difficult for aid policies in general, owing to the budget and debt crises faced by traditional donors. At the same time, crises might prompt changes that bring greater efficiency and facilitate monitoring and evaluation of AFT projects.

The successful transformation of global value chains into global development chains will take time and eventually happen with the maturity of international business, or it will require more cooperation between the public and private sectors. Joining forces in trade capacity building should help increase the efficiency and accountability of public aid, as well as the scaling up of successful private sector initiatives, and prevent behaviors that would adversely affect socioeconomic upgrading prospects in developing countries. Global development chains are responsible global value chains with a higher value for trade.

REFERENCES

- Agence Française de Développement (AFD). 2009. “Projet d’appui à la certification et à la commercialisation du caoutchouc au Cambodge.” Fiche de Performance des Projets Post-évalués. Paris: AFD.

- Agmon, T. 1979. “Direct Investment and Intra-Industry Trade: Substitutes or Complements.” In On the Economics of Intra-Industry Trade, edited by H. Giersch, 3–38. Tübingen, Germany: JCB Mohr.

- Antràs, P., and E. Helpman. 2004. “Global Sourcing.” Journal of Political Economy 112 (3): 552–80.

- Appelbaum, R. P., and G. Gereffi. 1994. “Power and Profits in the Apparel Commodity Chain.” In Global Production: the Apparel Industry in the Pacific Rim, edited by Bonacich and others, 42–64. Temple University Press.

- Bair, J. 2005. “Global Capitalism and Commodity Chains: Looking Back, Going Forward.” Competition and Change 9 (2): 153–80.

- Bair, J., and G. Gereffi. 2001. “Local Clusters in Global Value Chains: The Causes and Consequences of Export Dynamism in Torreon’s Blue Jeans Industry.” World Development 29 (11): 1885–1903.

- Baldwin, R. 2006. “Globalisation: The Great Unbundling(s).” Contribution to the project Globalisation Challenges for Europe and Finland, organised by the Secretariat of the Economic Council. https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/handle/10024/80508.

- ________. 2012. “Global Supply Chains: Why They Emerged, Why They Matter, and Where They Are Going. CEPR Discussion Paper 9103. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research. August.

- Baldwin, R., and S. Evenett. 2012. “Value Creation and Trade in 21st Century Manufacturing: What Policies for UK Manufacturing?” In The UK in a Global World: How Can the UK Focus on Steps in Global Value Chains That Really Add Value?, edited by David Greenaway, 71–128. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Bernard, A., and others. 2007. “Firms in International Trade.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 21 (3): 105–30.

- Bernard, A., M. Grazzi, and C. Tomasi. 2011. “Intermediaries in International Trade: Direct versus Indirect Modes of Export.” NBER Working Paper 17711. Cambridge, Mass.: National Bureau of Economic Research, December.

- Cattaneo, O., G. Gereffi, and C. Staritz, eds. 2010. Global Value Chains in a Postcrisis World: A Development Perspective. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Coe, N. M., P. Dicken, and M. Hess. 2008. “Global Production Networks: Realizing the Potential.” Journal of Economic Geography 8 (3): 271–95.

- Coe, N. M., and M. Hess. 2007. “Global Production Networks: Debates and Challenges.” Paper prepared for the GPERG workshop, University of Manchester.

- Dietzenbacher, E., and I. Romero. 2007. “Production Chains in an Interregional Framework: Identification by Means of Average Propagations Lengths.” International Regional Science Review 30 (4): 362–83.

- Fold, Niels, and Marianne Nylandsted Larsen. 2008. “Key Concepts and Core Issues in Global Value Chain Analysis.” In Globalization and Restructuring of African Commodity Flows, edited by Niels Fold and Marianne Nylandsted Larsen, 26–43. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Frederick, S. 2010. “Development and Application of a Value Chain Research Approach to Understand and Evaluate Internal and External Factors and Relationships Affecting Economic Competitiveness in the Textile Value Chain.” PhD dissertation, North Carolina State University.

- Gereffi, G. 1994. “The Organization of Buyer-Driven Global Commodity Chains: How US Retailers Shape Overseas Production Networks.” In Commodity Chains and Global Capitalism, edited by G. Gereffi and M. Korzeniewicz, 95–122. Westport, Conn.: Praeger.

- ________. 1999. “International Trade and Industrial Upgrading in the Apparel Commodity Chain.” Journal of International Economics 48 (1): 37–70.

- Gereffi, G., and K. Fernandez-Stark 2010. “The Offshore Services Value Chain: Developing Countries and the Crisis.” In Global Value Chains in a Postcrisis World. A Development Perspective, edited by O. Cattaneo, G. Gereffi, and C. Staritz, 335–72. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- ________. 2016. Global Value Chains Analysis: A Primer. 2nd ed. Duke Center on Globalization, Governance and Competitiveness. Duke University.

- Gereffi, G., J. Humphrey, and T. Sturgeon. 2005. “The Governance of Global Value Chains.” Review of International Political Economy 12 (1): 78–104.

- Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI). 2012. GFSI Guidance Document. 6th ed., Issue 3, Version 6.2. Paris: GFSI.

- Grossman, G., and E. Rossi-Hansberg. 2006. “The Rise of Offshoring: It’s Not Wine for Cloth Anymore.” In The New Economic Geography: Effects and Policy Implications, 59–102. Jackson Hole Conference Volume. Federal Reserve of Kansas City.

- ________. 2008. “Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory of Offshoring.” American Economic Review 98 (5): 1978–97.

- Grossmann, V., and D. Stadelmann. 2012. “Wage Effects of High Skilled Migration: International Evidence.” IZA Discussion Paper 6611. Bonn, Germany: Institute for the Study of Labor. May.

- Grubel, H., and P. Lloyd. 1975. Intra-Industry Trade: The Theory and Measurement of International Trade with Differentiated Products. London: Macmillan.

- Haddad, M., and B. Shepherd. 2011. Managing Openness: Trade and Outward-Oriented Growth after the Crisis. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Havranek, T., and Z. Irsova. 2011. “Estimating Vertical Spillovers from FDI: Why Results Vary and What the True Effect Is.” Journal of International Economics 85 (2): 234–44.

- Henderson, J., and others. 2002. “Global Production Networks and the Analysis of Economic Development.” Review of International Political Economy 9 (3): 436–64.

- Hopkins, T., and I. Wallerstein. 1977. “Patterns of Development of the Modern World-System.” Review 1 (2): 111–45.

- Hudson, R. 2004. “Conceptualizing Economies and Their Geographies: Spaces, Flows and Circuits.” Progress in Human Geography 28: 447–71.

- Hummels, D., J. Ishii, and K. M. Yi. 2001. “The Nature and Growth of Vertical Specialization in World Trade.” Journal of International Economics 54 (1): 75–96.

- Humphrey, J., and H. Schmitz. 2002. “How Does Insertion in Global Value Chains Affect Upgrading in Industrial Clusters?” Regional Studies 36 (9): 1017–27.

- Jefferson, G. 2008. “How Has China’s Economic Emergence Contributed to the Field of Economics?” Comparative Economic Studies 50 (2): 167–209.

- Jin, K. 2012. “Industrial Structure and Capital Flows.” American Economic Review 102 (5): 2111–46.

- Jones, C. 2011. “Intermediate Goods and Weak Links in the Theory of Economic Development,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 3 (April): 1–28.

- Jones, R., and H. Kierzkowski. 1990. “The Role of Services in Production and International Trade: A Theoretical Framework.” In The Political Economy of International Trade, edited by R. Jones and A. Krueger, 31–48. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- ________. 2001. “A Framework for Fragmentation.” In Fragmentation: New Production Patterns in the World Economy, edited by S. Arndt and H. Kierzkowski, 17–34. Oxford University Press.