2

ANTIDUMPING AND MARKET COMPETITION

IMPLICATIONS FOR EMERGING ECONOMIES

CHAD P. BOWN

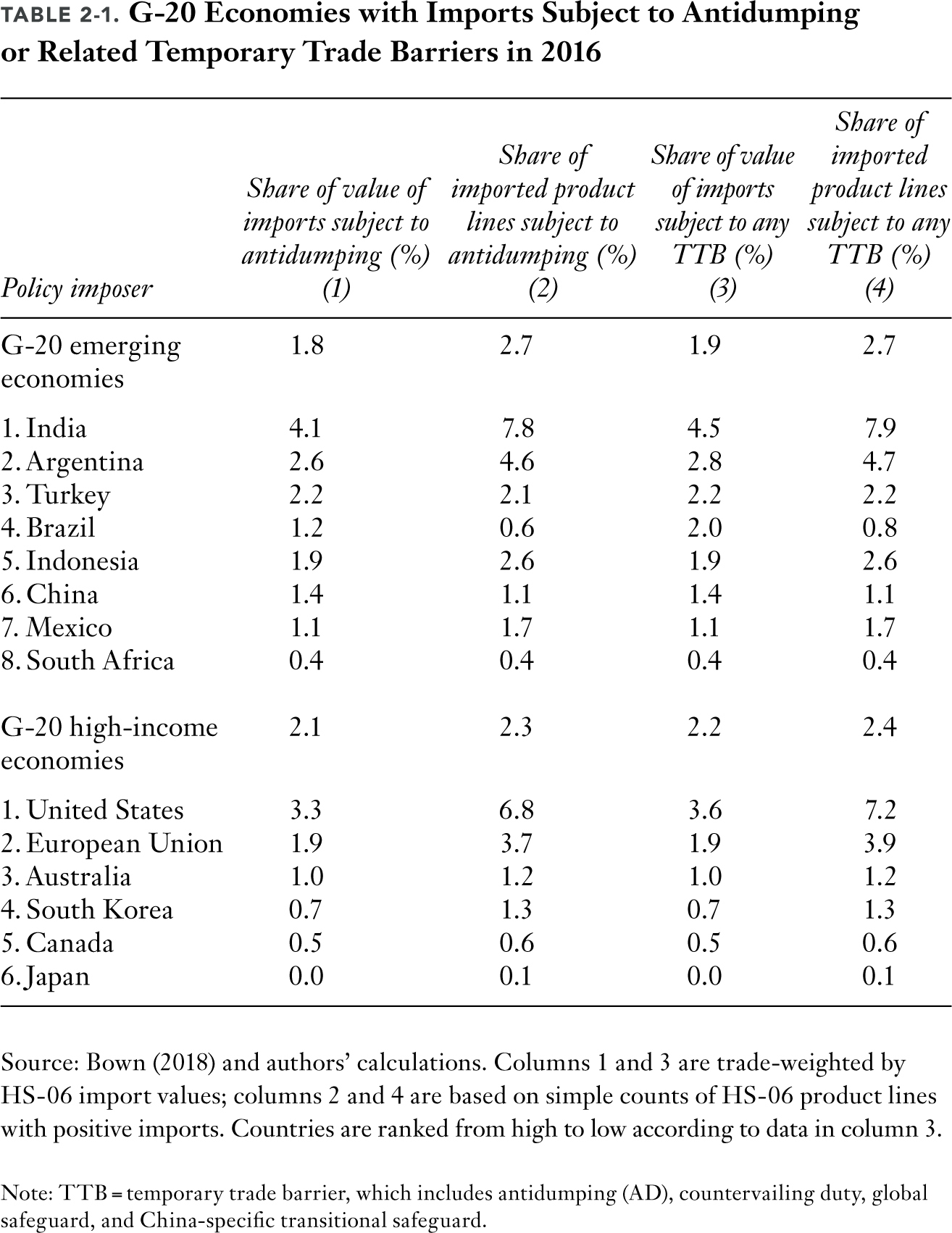

In the first fifteen years of the twenty-first century, antidumping use by the major emerging economies became a much more important feature of the World Trade Organization (WTO) system, rivaling its use by industrialized countries. By 2016, India, Turkey, Argentina, and Indonesia were each subjecting at least as large a share of the value of their imports to trade-distorting antidumping measures as the European Union, one of the largest “historical” users of the policy. Other emerging economies like Brazil and China were not far behind. Moreover, what had begun a century earlier as a policy mainly limiting North-North trade, and then later North-South trade, was rapidly emerging as a significant barrier to South-South trade.

Antidumping laws originated as the international counterpart of the domestic antitrust (competition) policies that industrialized countries began to enact in the late 1800s. Their initial purpose was to protect domestic consumers from predatory actions on the part of foreign suppliers (Viner 1923). However, antidumping remained an insignificant element of trade policy until the late 1970s. Tariffs on many products were still high enough to make competing imports only a minor threat to domestic producers. The criteria for antidumping protection were also difficult enough to satisfy that the United States, later the most important user of antidumping, did not impose any antidumping duties in the 1950s, and only about 10 percent of US cases in the 1960s resulted in duties (Irwin, 2005a). But by the 1980s, modifications to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) made as a result of the 1979 completion of the Tokyo Round of GATT negotiations had “transformed this little used trade statute into the workhorse of international protection” (Prusa and Skeath 2002)—at least for the five users that initiated nearly all antidumping cases in the 1980s (the United States, Canada, the European Community, Australia, and New Zealand). The first change broadened the definition of “less than fair value” to include sales below cost as well as price discrimination between home and export markets. The second change weakened the injury requirement by reducing the emphasis on a causal link between dumped imports and material injury to the competing domestic industry. Over the next fifteen years, the antidumping activity of the historical users soared.

Along with the greatly increased use of antidumping came new concerns. Over the years, laws and procedures had evolved so as to weaken the original link between antidumping and threat of predation. Moreover, expanded use of antidumping especially, but also of countervailing duties and other forms of contingent protection, raised a different concern about the effect of these policies on conditions of market competition. Concern that injurious dumping might inhibit market competition over the long run gave way to a worry that antidumping laws were not designed to differentiate predatory dumping from ordinary lower-cost import competition and thus were being used purely as a protectionist device. That was followed by concern that existence and abuse of antidumping might actually lead to more collusive outcomes and less competitive markets than in the absence of antidumping laws. These fears spurred a sizable theoretical and empirical literature that peaked in the late 1990s.

I thus begin this chapter by reviewing and updating the normative case for antidumping. Antidumping started as an international extension of efforts via antitrust policy to prevent losses in overall economic well-being that result from the exercise of monopoly power in the domestic market. I then consider the literature on the US and European application of antidumping in the 1980s and 1990s, in which some analysts conclude that, rather than preventing foreign suppliers from gaining market power, antidumping measures may instead facilitate cartelization of the affected market. When this happens, domestic import-competing producers still gain, but overall economic well-being is reduced.

The examination continues with an analysis of important changes in the conditions of the world economy since the 1990s. I explore questions relating to the market-competition effects of antidumping in light of recent evidence that policies such as antidumping have proliferated globally and are now used much more by emerging market economies than by the industrialized economies. Has the case for, or against, antidumping changed for these as well as for the high-income economies, especially given the significant developments in world trade since the 1990s? These developments include the emergence of important new traders, most notably China; fragmentation of the value chain in many industries; and the increased role in world trade of multinational firms, including some based in countries that had little or no outward foreign direct investment until the twenty-first century.

The rest of the chapter proceeds with a brief review of the institutional evolution of antidumping laws from the perspective of competitiveness concerns; a description of the theoretical and empirical research from the 1980s and 1990s that analyzes and documents the market-segmenting consequences of contingent protection; and an investigation of the argument that the situation has changed somewhat in the 2000s. In particular, I explore the implications for emerging markets.

ANTIDUMPING PROVISIONS IN HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Why should trade arrangements like the GATT/WTO, whose stated purpose is to promote freer and more transparent conditions of trade, include provisions that allow members considerable freedom to protect domestic producers in a manner that is far from transparent?1 The question is particularly relevant today, when a significant share of all trade is subject to protection via antidumping measures, along with other types of unilateral, nontransparent contingent protection, collectively known as temporary trade barriers (TTBs). During the recent global recession, domestic political pressure for protection rose around the world. Through use of antidumping and other WTO-legal TTBs, many members were able to increase the extent of protection for domestic industries while still complying with their WTO commitments (Bown 2011a, 2011b).2

Some economists justify antidumping as one of the important flexibilities that the GATT/WTO trade agreements provide to allow countries facing political or economic shocks to escape temporarily from their commitments to keep tariffs low. Antidumping also allows WTO members to undo some liberalization while maintaining overall cooperation with respect to trade policy—that is, without undermining the entirety of the agreements.3 Indeed, evidence for the United States suggests that antidumping protection is more likely to be obtained in the face of economic shocks that put trade policy cooperation under additional stress (Bown and Crowley, 2013), while evidence from other countries indicates that antidumping may be used where overall tariff protection has recently been reduced (Bown and Tovar 2011).4 Finger and Nogues (2005) present a number of case studies for Latin American economies suggesting that antidumping and other TTBs allowed governments to manage domestic political pressures for import protection while maintaining a generally liberal trade policy.5 In other words, some controlled access to new protection may be the price of maintaining an open trading system. Implicit is the idea that overall gains from trade in a particular sector must sometimes be sacrificed in order to appease domestic groups that are harmed by competing imports. Vandenbussche and Zanardi (2010) quantify this implied sacrifice by estimating the effect of antidumping laws on aggregate trade flows between new adopters and their trading partners.6

But the early history of antidumping reflects a completely different rationale—one based on the possible use by foreign suppliers of temporarily low export prices to achieve market power. National antidumping laws in the United States and other industrialized countries predate the original GATT by several decades, and in their earliest versions were closely linked to antitrust policy. In 1904, Canada became the first country to impose an antidumping law, closely followed by New Zealand (1905) and Australia (1906). The first U.S antidumping statute (1916) was very narrow in its scope, requiring not only a low price of imports relative to some standard but also evidence of intent on the part of foreign suppliers to injure current or potential domestic producers and/or to achieve a monopoly position in the relevant domestic market—what came to be called predatory dumping. In terms of language, the original antidumping laws closely resemble antitrust statutes that address predatory pricing in domestic competition.

As with domestic antitrust laws, the original purpose of antidumping laws was to protect consumers by preventing abuse of market power. Similar to antitrust, the objective was to prevent losses of overall national well-being, rather than simply to prevent losses to import-competing producers, although the latter would be an inevitable result of applying the law. Under the original law, dumping was defined as setting an export price below that charged in the exporter’s home market—that is, price discrimination, with no reference to cost of production. Moreover, rather than antidumping duties, the US law, similarly to antitrust statutes, called for importers of dumped goods to pay triple damages.

But despite the common roots of antidumping and antitrust laws, the criteria for intervention in the two bodies of laws soon diverged (Messerlin 1994). The US antidumping law was broadened in 1921 to allow antidumping action for any case in which the import price was below that in the home market, regardless of intent. Under the 1979 Trade Act, the scope was increased again by including dumping defined in terms of pricing below a constructed measure of average cost, including a required 8 percent profit margin (Shin 1998). Perhaps most important, while the goal of antitrust law was to protect overall national well-being by limiting the exercise of monopoly power, antidumping focused on protection of the domestic petitioners, without regard for effects on consumers.7

Did the original antidumping statutes address a real problem? Was predatory dumping an important policy concern at the time? Viner (1923, 61) refers to “writers hostile to Germany” who charged that “much of German dumping was actuated by predatory motives.” However, Viner also notes the lack of conclusive evidence, pointing out that no such charges had been made against the powerful German kartells before the outbreak of war in 1914. But Sidak (1982) cites evidence from contemporary economic thought as well as legal commentary that prevention of monopolization, not simple deterrence of foreign competition, was the intent of the original 1916 US antidumping law. Sykes (1998) likewise finds evidence that concerns regarding predation motivated early Canadian and US antidumping statutes. Yet by the 1980s, the potential for protectionist effect, if not intent, of antidumping action had become clear. One important reason is that, in contrast to US antitrust law, application of antidumping does not require evidence that alleged foreign intent to achieve market power has a reasonable chance of success.

DUMPING, ANTIDUMPING, AND CONDITIONS OF MARKET COMPETITION

This section reviews the theory and evidence through the 1990s on the relationship between dumping, antidumping trade policy, and the competitiveness of markets.

Theory: Dumping and Overall Economic Well-Being in the Importing Country

Willig (1998) provides a theoretical survey of possible motivations for dumping and the associated effects on overall economic well-being in the importing country. He examines several types of dumping that have little or no relationship to creation of market power and distinguishes these from two categories of dumping that do aim at establishing market power. In the first group are simple price discrimination, cyclical dumping, and dumping by nonmarket economies. In all three cases, the likely effect on the importing country is to make the domestic market more, rather than less, competitive. Thus, as with other types of trade, overall economic well-being in the importing country is likely to be increased rather than reduced, with benefits to consuming households or industries outweighing losses to import-competing producers.

In contrast, dumping that does aim at establishing and exploiting market power can indeed impose losses on the importing country. The simpler form of potentially harmful dumping is predatory dumping, the international equivalent of predatory pricing: sellers accept losses in the short run in order to achieve monopoly profits further in the future. The foreign seller’s low price is intended to force domestic competitors to exit the market, thereby allowing the foreign seller to secure market power and future monopoly profits. But the industrial organization literature suggests that the necessary conditions for successful predatory pricing are unlikely to be satisfied, and the same qualifications cast doubt on the importance of this behavior on the part of foreign producers. For the strategy to be successful, the foreign producer must be better able than the domestic incumbent firms to withstand the short-term losses associated with a low price and must have the production capacity necessary to serve a significant share of the importing country market at that low price. Moreover, the domestic industry must be characterized by barriers to entry and also to reentry by domestic firms once the foreign producer attempts to exploit its monopoly power by raising price. Likewise, actual and potential foreign supply must be highly concentrated; otherwise, competition among import suppliers would force the price of imports back toward the competitive level.

Strategic dumping is a more complicated form of dumping that is also potentially harmful to the importing country.8 Dumping in this case exploits static or dynamic scale economies in the relevant industry, a condition inconsistent with perfect competition. US firms leveled allegations of strategic dumping in the 1980s after exporters in Europe and Japan began to challenge the US technological lead in research and development–intensive products. In strategic dumping, low-priced exports, possibly sold below full cost but almost always for less than the price in the exporter’s home market, are used to increase the firm’s or industry’s size,9 thereby achieving scale economies that result in lower costs or better products, and thus higher profits in the future. As domestic purchases shift toward imports, the market share of domestic suppliers is correspondingly reduced, with opposite effects on scale and profitability. Domestic import-competing suppliers may therefore be forced out of the market because they have higher costs or less advanced products. However, in contrast to predatory dumping, strategic dumping may be profitable for exporters even if it does not cause exit by domestic import-competing suppliers but merely raises the scale of exporter production while decreasing the scale of competing domestic firms.

As with predatory dumping, stringent conditions are required for this strategy to be profitable, and further conditions are required for strategic dumping to harm overall economic well-being in the importing country. First, the exporter’s production must be large enough to achieve the relevant scale economies, while production by competing domestic firms must be small enough to prevent them from capturing similar benefits. Thus, if the strategic dumping story has any practical relevance, it would be for large exporters that are in competition with small domestic firms. Yet most antidumping cases during the 1980s and the early 1990s were brought by importing countries with large markets for the designated products and large domestic suppliers against exporting countries with smaller domestic markets and smaller producers, with the United States and the European Union serving as the “domestic” economies and thereby accounting for the largest number of antidumping initiations.10

A requirement for exporters to profit from strategic dumping is that the exporter’s own market be protected—by trade policies, tastes, transportation costs, or more subtle barriers—from penetration by suppliers in the importing country, thus allowing producers to enjoy a profitable “sanctuary market.” Countries appearing to provide this kind of sanctuary market for some products (such as autos, consumer electronics) included Japan in the 1970s and 1980s and South Korea in later decades. Profits on domestic sales then allow exporting at a price below average cost—that is, dumping. Some of the emerging economies that have been recent targets of antidumping do indeed protect their domestic markets for like products, but with the notable exception of China, these exporters’ domestic markets are typically small relative to those of the importers. Thus it is hard to imagine that domestic producers in the import-competing country suffer any significant scale disadvantage caused by exclusion from these markets.11

A loss in overall economic well-being in the importing country due to strategic dumping also requires that foreign supply be highly concentrated or that the exporting country government control total export quantities. Otherwise, competition among exporters would force the price down toward average cost. In this case, consumers in the importing countries rather than the foreign suppliers would be the main beneficiaries of the scale economies captured by exporters. Of course, import-competing firms would lose, and the domestic industry might even disappear, though this could be true regardless of the reason why exporters’ costs were lower. But the exporting countries most often alleged to be dumping (Japan in the 1980s, China today) have found effective ways to coordinate exporter behavior so as to limit total exports. The same potential for control might also exist when suppliers are subsidiaries in various exporting countries of the same multinational firm. Thus predation supported by the cost advantage of scale economies cannot be ruled out a priori. Nonetheless, for most of the relevant products, prices continued to fall even after domestic suppliers left the industry, rather than rising as exporters attempt to exploit their increased market power. Documented exceptions to this pattern have resulted more from trade measures (for example, the 1986 US-Japan semiconductor agreement discussed later) than from successful predation by exporters.

Evidence through the 1990s: Did Antidumping Target Predatory or Strategic Dumping?

Empirical evidence from the 1980s and 1990s suggests that antidumping law in its more recent expanded form was typically applied in cases where even the necessary conditions for successful predatory or strategic dumping were not satisfied. As Shin (1998) argues, dumping criteria based only on price or cost do not offer a practical method of distinguishing cases in which dumping is predatory from ones in which consumers are likely to benefit from increased competition. Accordingly, he searches for structural characteristics of markets in which predatory dumping is likely to be a profitable strategy in the long run. Such a market must be relatively concentrated, with significant barriers to new entry as well as to reentry by firms that have previously exited. Also, exporters to that market who are alleged to be dumping should be relatively concentrated, and import penetration into the market should be high or rapidly growing.

Shin examines US dumping cases for the period 1980 through 1989. For the industries in which dumping was found, he determines whether the structural characteristics necessary for successful predation were present—that is, whether damage to the United States from predatory dumping might plausibly be expected. He concludes that the domestic market-concentration criterion for successful predatory dumping was satisfied in only 39 of 282 cases with nonnegative outcomes—less than 14 percent of the cases. Moreover, this figure is an upper limit, since Shin does not, for example, go on to determine whether the concentrated markets were protected by barriers to entry or reentry, or whether foreign export supply was concentrated. Thus only rare cases among instances of confirmed dumping were likely to involve anticompetitive intent on the part of foreign firms. As a consequence, Shin concludes that, rather than protecting US consumers from predatory behavior, most applications of antidumping policy during the 1980s probably reduced US welfare by limiting beneficial import competition—though of course still increasing the profitability of domestic suppliers as well as those foreign exporters not subject to the antidumping actions.

In a similar study of dumping cases in the European Union during the period 1980–97, Bourgeois and Messerlin (1998) conclude that an even smaller share, around 2 percent, satisfied the conditions necessary for predatory behavior on the part of exporters alleged to be dumping. Like Shin (1998), they do not examine whether exporters had the capacity to exercise and maintain market power and thus to profit from earlier dumping, a second criterion that would have ruled out predatory behavior for at least some of these cases. As in the US cases, antidumping merely protected domestic import-competing industries from the effects of import competition, but at the expense of domestic users of the affected products.

While Bourgeois and Messerlin (1998) examine EU cases only to determine whether predatory behavior is plausible, Messerlin and Noguchi (1998) look specifically at electronic products such as television sets, compact disk players, microwave ovens, mobile phones, and photocopiers, where economic analysis of the 1980s highlighted the possibility of strategic behavior by exporters seeking to exploit static or dynamic scale economies. During this period, antidumping activity in the United States and Europe targeted mainly Japanese firms (about half of all cases) but also firms in Korea (one-quarter of all cases), and firms in Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore, and China (together about 20 percent of all cases). Messerlin and Noguchi found that about 80 percent of antidumping cases brought ended with “severe” antidumping measures—median tariffs or tariff equivalents around twice as high as the corresponding applied tariffs.

Messerlin and Noguchi examine the cases of color television sets and compact disk players to determine whether the three conditions required for profitable strategic dumping were satisfied. First, was the exporter’s own market for the product protected? Second, was the exporter’s own market large enough relative to the size of unprotected markets to put competing producers at a disadvantage? And third, were there static or dynamic scale economies in the relevant industry? For both products, a detailed examination reveals that even the necessary conditions for predatory or strategic dumping were not satisfied. With regard to strategic dumping, the evidence suggests that the European Union did much more than Japan to limit imports into its own domestic color television market and thus allow the domestic industry to capture possible benefits from scale economies. A US predatory dumping case brought by Zenith against twelve Japanese exporters of color televisions (the Matsushita case) made it to the US Supreme Court. The court concluded that if the firms’ low export prices had indeed been motivated by predation, it would have taken more than forty years to recoup their initial losses in the US market (Mavroidis, Messerlin, and Wauters 2008, 13).

Irwin (1998) examines the experience of the US semiconductor industry, which brought dumping charges against Japanese producers in 1985. An important aspect of the case is that, unlike color television sets or compact disk players, semiconductors were an intermediate good, and the case thus affected not only the import-competing industry but also the downstream US computer industry. Irwin does not reach a firm conclusion regarding strategic dumping because of conflicting evidence as to whether Japan’s market for semiconductors was open to competing imports. However, he labels the case as one of “textbook cyclical dumping” in which world prices of semiconductors dropped sharply following a downturn in demand.12 The case ended with a negotiated settlement in which Japan agreed to cost-based, company-specific price floors for their US sales as well as quantitative targets for their foreign market share; both measures hindered active competition among Japanese exporters. Some US computer companies responded to the price floors imposed on imports of critical semiconductor inputs by shifting assembly operations to other countries.13 While the antidumping measures did not prevent US producers of semiconductors from exiting, they did encourage the entry of South Korean producers, but that was not enough to prevent prices to US buyers from rising sharply when demand rebounded.

Theory: How Antidumping Policy Can Worsen Conditions of Market Competition

I have noted that the original justification for antidumping laws was to prevent predation in the domestic market by foreign exporters—that is, to maintain competition among suppliers. But by the 1980s, broadening of the definition of dumping and the conditions under which affected domestic producers could obtain relief from competing imports had transformed antidumping into a particularly flexible, and therefore increasingly popular, means of increasing a domestic industry’s protection without violating GATT commitments. The trade policy literature of the 1980s and 1990s went further, turning the original justification for antidumping—as a means to prevent monopolization of the domestic market—on its head by demonstrating that antidumping usually increases producers’ market power and can even be used to create and defend cartels.

Effects of antidumping on market competition can come through several channels. First, as with other forms of protection, it is likely to reduce the total number of firms active in the domestic market and thereby to reduce the elasticity of demand facing each of them. Even if firms do not collude, the effect will be to raise the equilibrium markup of price over cost. Second, because antidumping can raise the cost of an imported input, it provides a means by which a more efficient competitor in the domestic market can force out a less competitive domestic rival.14 Moreover, because antidumping cases target specific foreign exporters in specific locations, they provide a useful means of policing a tacit collusive arrangement. Finally, in the longer run even the threat of antidumping or other increases in protection can provide an inducement for foreign exporters to relocate their production via direct investment in the importing country.

A key insight underlying much of this literature is that antidumping measures are imposed (or not) as a response to market outcomes. Thus both domestic and foreign suppliers act strategically, taking into account effects on the behavior of other suppliers and the subsequent endogenous actions of trade authorities.15 Blonigen and Prusa (2003) survey a range of theoretical findings. As in the literature on (domestic) imperfect competition, a wide range of outcomes can be obtained depending on whether firms set price or quantity and whether evidence of dumping or of injury is more important in the actions of trade authorities. They note that it is possible to obtain “just about any combination of distorted market effects, depending on the characteristics of the strategic game being played by the firms” (Blonigen and Prusa 2003, 241). Since the theoretical games begin from an equilibrium with distortions, antidumping can even result in a net increase in overall economic well-being in the importing country.

Mixed Evidence: Antidumping, Cartel Formation, and Other Competitiveness Concerns

As noted previously, empirical evidence established that the vast majority of antidumping cases filed during the 1980s and 1990s involved products whose predatory or strategic dumping would be highly unlikely to cause a downturn in overall economic well-being. Evidence in some of these cases suggests that antidumping actions may have had an effect opposite to its supposed goal—that is, by limiting efficient foreign competition, antidumping actually facilitated cartelization of the market. The likelihood of such an outcome is especially strong when nontariff antidumping measures such as voluntary export restraints or minimum price agreements are used.

For the European Union, Messerlin (1990) documents a link between antidumping and cartel formation with “twin” antidumping and antitrust cases—cases in which the same product was involved in an antidumping case and also an anticartel case. For the period of the 1980s, there were nearly thirty such anticartel cases, constituting about one-quarter of all anticartel cases during the decade. The one hundred related antidumping cases likewise constituted about one-quarter of all antidumping cases during the decade. Messerlin argues that termination of antidumping cases with a finding of “no dumping” may result when competing firms reach private collusive agreements. He provides detailed evidence for two chemical industry cartels—polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and low-density polyethylene (LdPE)—in which antidumping cases helped to enforce cartel arrangements. Although members of both cartels were later required to pay substantial fines as a result of antitrust actions, the strategy was nonetheless highly profitable overall for the firms involved.

For the United States, the evidence of the impact of antidumping on conditions of competition is mixed. Staiger and Wolak (1994) examine antidumping cases in the period 1980–85 and find that the mere filing of an antidumping investigation can have significant negative effects on trade, even without the imposition of a new tariff. Prusa (1992) notes that more than one-third of US antidumping petitions filed from 1980 through 1988 were withdrawn, which he interprets as possible evidence of a collusive agreement having been reached by domestic and foreign firms. This pattern continued into the 1990s, with about a quarter of all antidumping petitions from 1980 through 1998 being withdrawn (Blonigen and Prusa, 2003). Prusa argues that domestic firms involved in antidumping cases may be exempt from antitrust actions under the Noerr-Pennington doctrine. However, Taylor (2004) challenges this argument, as well as Prusa’s assumption that withdrawn petitions are a signal of collusion. He points out that earlier research, notably by Prusa (1992), had aggregated withdrawn and settled cases. Taylor uses data only for antidumping cases filed from 1990 through 1997 that ended in a withdrawn petition without a suspension agreement or a voluntary restraint agreement. From an examination of monthly import data, Taylor finds no evidence of collusion in these cases. By design, Taylor’s analysis omits cases settled through collusion-friendly measures such as price floors or quantitative restrictions (such as voluntary export agreements).16

Barfield’s (2003) review of the effects of antidumping actions in several US high-technology industries is relevant here because these industries are precisely the kind where the necessary conditions for predatory or strategic dumping are most likely to be found. Yet Barfield concludes that “while the application of antidumping laws is problematic in any sector, it is particularly troublesome in high-technology sectors” (Barfield 2003, 5). The cases Barfield reviews are consistent with Messerlin’s (1990) characterization of antidumping as a policy more likely to impede than to protect competition in the market of the importing country. As such, antidumping during this period was likely to benefit producers (in some cases including foreign producers) at the expense of consumers, the same result as with other types of protection. Barfield argues that antidumping is futile as a means to save uncompetitive companies and sectors, while it is damaging to market competition and impedes innovation—the lifeblood of high-technology industries.

Like Finger (1993, chap. 4), Barfield favors complete elimination of antidumping, with substitution of safeguard actions where domestic firms need more time to adjust to changing market conditions, while leaving evaluation of anticompetitive effects from possible predation to the antitrust authorities. Of course, both authors acknowledge that political opposition makes this “best” course of action unlikely. But Messerlin (1994) points to a variety of pitfalls related to simply replacing antidumping by competition rules. Messerlin’s own preference—at least as a short-run solution until countries can agree on a common set of competition rules—is sequential enforcement, in which antitrust or competition authorities are explicitly mandated to evaluate potentially anticompetitive consequences of actions taken by antidumping authorities. Ideally, this ex post review process would discourage application of antidumping for anticompetitive ends.

One recent instance of antidumping used to protect domestic high-technology production was the US decision in May 2012 to apply antidumping duties on solar panels from China.17 The president of SolarWorld USA, a US subsidiary of Germany’s largest solar panel producer and the lead complainant in the case, called the US measure a “positive step” needed because “Chinese firms are seeking ‘total dominance’ of the sector that could lead to monopoly pricing in the long term” (Johnson and Sweet, 2012). In July 2012, SolarWorld USA’s German parent led a group of manufacturers filing a similar complaint with the European Commission (Nicola and Roca 2012).18

Given the large number of producers in each market, as well as producers in many other countries, future predation by Chinese exporters seems a remote possibility.19 Yet China has already demonstrated its ability to restrict exports ranging from apparel to raw materials and rare earths—a necessary condition for monopoly pricing. Even so, China’s primary reason for supporting its solar firms is most likely similar to that of the United States—to maintain employment and promote the adoption of solar power. While US antidumping may indeed save some jobs in domestic solar panel factories at least in the short run, this will come at the cost of slowing US adoption of solar technology and thus reducing growth of employment in the downstream sector that installs solar panels. Moreover, China quickly retaliated against the US measure with its own investigation of US government support for clean-energy projects in five states (Areddy and Ma 2012), potentially affecting US hopes of increasing clean-energy exports to China. China also subsequently retaliated by imposing antidumping duties on imports of a key input—solar grade polysilicon—from both the United States and the European Union.

DUMPING, ANTIDUMPING, AND MARKET COMPETITION IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

The broad consensus in the international trade literature of the 1980s and 1990s was that antidumping, whatever its original justification, had become nothing more than “ordinary protection, albeit with a good public relations program” (Finger 1993, chap. 2). Many economists went further, arguing that antidumping had become even worse than most ordinary protection because antidumping actions often ended in measures like voluntary export restrictions and price undertakings that restricted competition among suppliers. However, the subsequent evolution of world trade and trade policy justifies a fresh look at the classic concerns of dumping. Here I focus on three important changes: increased use of antidumping by emerging economies, increased fragmentation of production with a major role for multinational firms, and the rise of China as a major exporter. Under these new conditions, what are the likely consequences for competition in importing countries of dumping and antidumping?

Antidumping Use by Emerging Economies and Its Potential Impact in South-South Trade

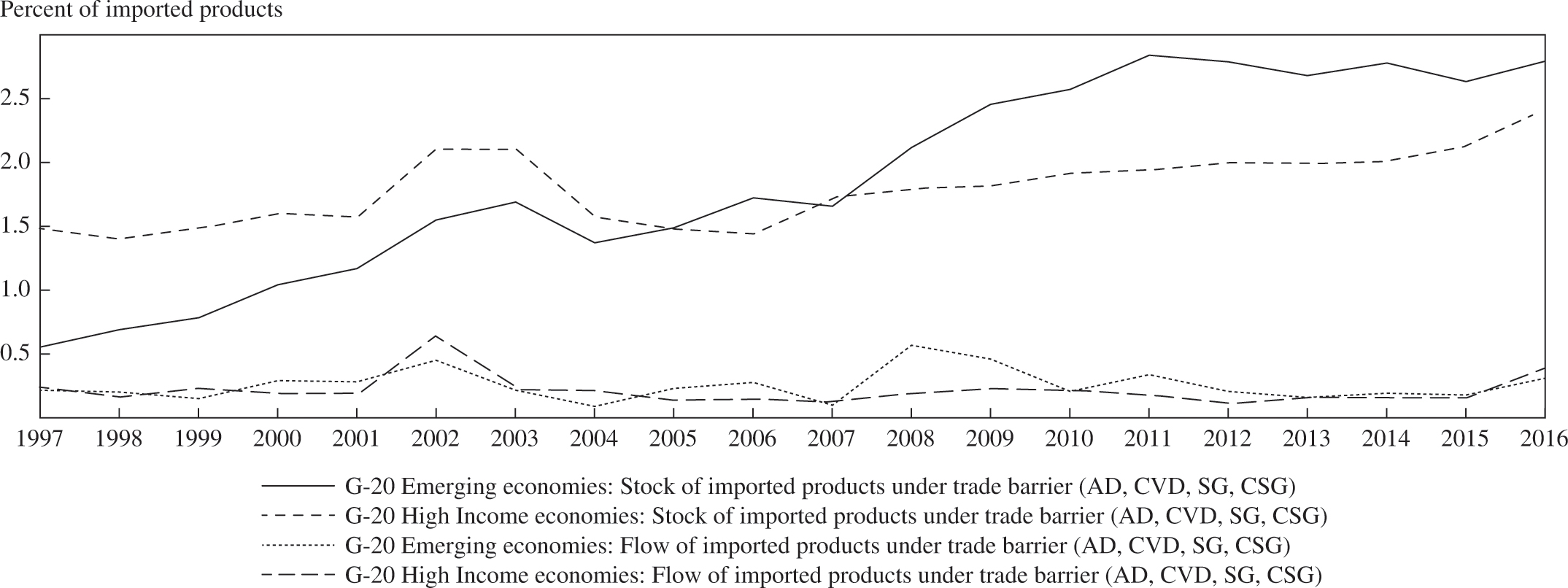

Through the early 1990s, just five industrialized countries initiated almost all antidumping cases worldwide. But in recent years the use of antidumping and related temporary trade barriers by high-income countries has been leveling off, while some large emerging economies have become intensive users (Bown 2011a, 2011b). Figure 2-1 illustrates the changing share over the period 1997–2016 of all six-digit Harmonized System products imported by the G-20 economies collectively that were subject to antidumping or another temporary trade barrier (TTB) such as safeguards or countervailing duties.20 As figure 2-1 indicates, by 2016 roughly 2.8 percent of all six-digit products imported by the major emerging economies were subject to some sort of TTB; this share rose steadily in the 2000s, roughly doubling between 2004 and 2011. For the high-income economies, by 2016 roughly 2.4 percent of all six-digit imported products were subject to some TTB. This share had increased recently after holding relatively constant over the previous fifteen years and, perhaps surprisingly, did not rise substantially even during the Great Recession after 2007.

FIGURE 2-1. G-20 Imports Subject to Formal Temporary Trade Barriers, 1997–2016

Source: Constructed with data from Bown (2018). Percentages based on counts of six-digit HS import products—that is, the number of product lines subject to any temporary trade barrier in that year relative to the total number of product lines with positive imports. (These percentages do not measure the share of trade value subject to temporary trade barriers.)

Notes: AD = antidumping; CVD = countervailing duty; SG = global safeguard; CSG = China-specific transitional safeguard. G-20 high-income economies include Australia, Canada, the European Union, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. G-20 emerging economies include Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, South Africa, and Turkey, and exclude Mexico.

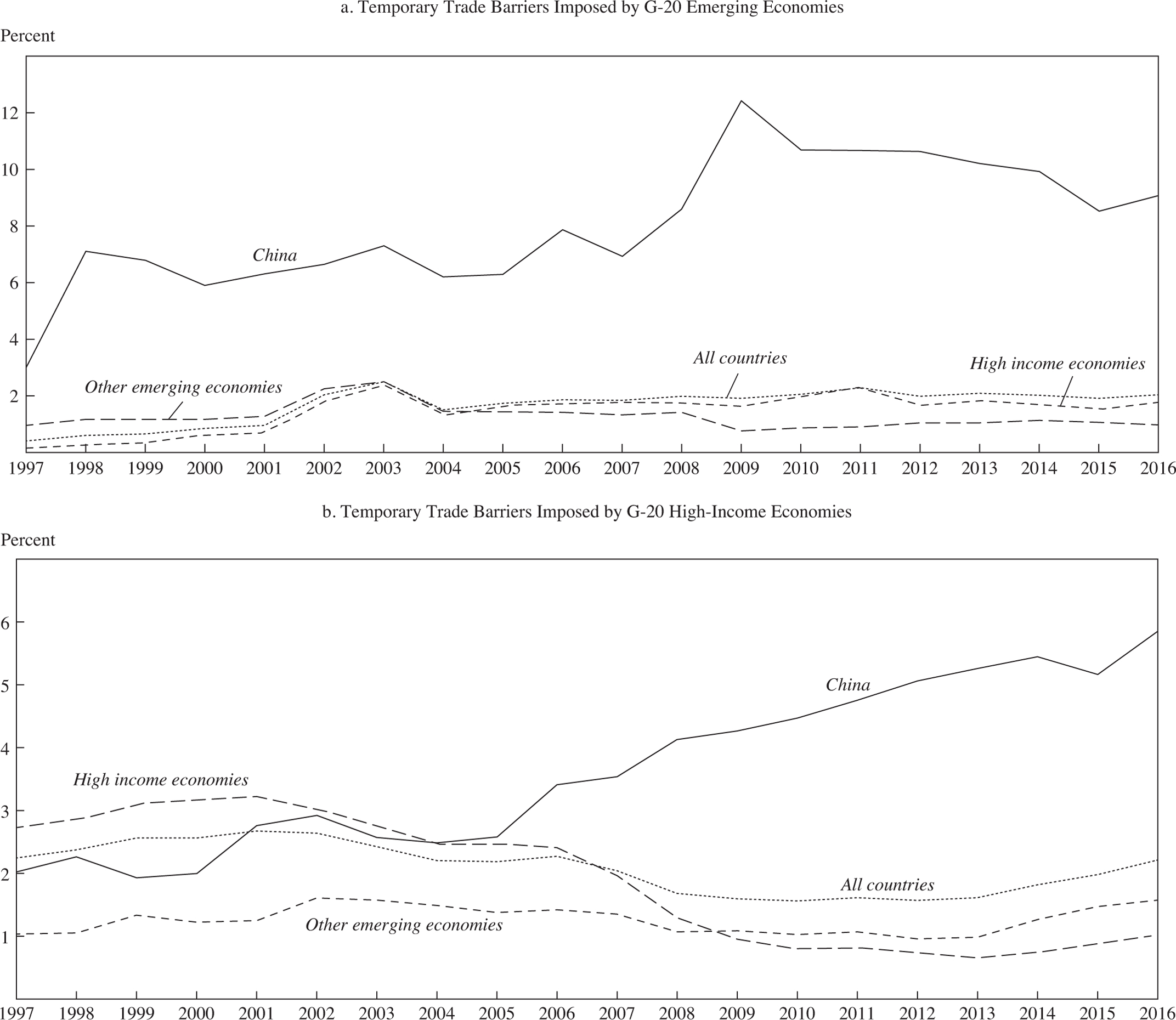

Figure 2-2 documents the changing incidence of these TTBs on exporting economies. Most striking is the impact on China’s exports—by 2016, more than 9 percent of China’s exports by value to other emerging economies were subject to a TTB, roughly 50 percent higher than the share in 2004. TTBs imposed by high-income economies show a trend in disproportionately targeting China, though the scale is less dramatic; by 2016, 5.8 percent of Chinese exports to high-income markets were subject to a TTB, up from 2.5 percent in 2004. Figure 2-2a documents that emerging economies have also frequently targeted exports from other emerging markets apart from China, though at a lower level. Over the period 2001–16, on average 1.3 percent of other (non-China) emerging economy exports to emerging economies were subject to a TTB in any given year.21

Three main points arise from the data. First, use of antidumping and other TTBs by emerging economies has been increasing, and these policies affect a significant range of imported products. Second, China has become the dominant target for both emerging-economy and high-income users of TTBs, with the rate of increase accelerating for emerging-economy users. Third, emerging economies have also frequently targeted imports from other (non-China) emerging-market exporters. These recent patterns in use of antidumping and other TTBs raise the question of how earlier research on antidumping and conditions of market competition may apply to emerging economies, both as users and as targets.22 Table 2-1 summarizes G-20 economy specific statistics.

Fragmentation of Production and Multinational Activity

Fragmentation of the value chain in the production of many traded goods has been increasing over the last 40 years (Hummels, Ishii, and Yi 2001; Johnson and Noguera 2017), and the share of trade mediated by affiliates (and/or) parents of the same multinational firm rather than through arm’s-length transactions is large. For example, nearly half of total US imports in 2000 were intra-firm transactions.23 Increased fragmentation of production and trade between related parties complicate both the political economy of antidumping and its potential impact on conditions of market competition.

FIGURE 2-2. Export Sources Subject to G-20-Imposed Formal Temporary Trade Barriers, 1997–2016

Source: Constructed with data from Bown (2018), trade-weighted averages of temporary trade barrier coverage.

Note: G-20 emerging economies include Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, South Africa, and Turkey, and exclude Mexico. G-20 high-income economies include Australia, Canada, European Union, Japan, South Korea, and the United States.

Antidumping measures affecting intermediate inputs raise the costs to firms further downstream in the supply chain, thereby hurting overall competitiveness relative to firms and production locations unencumbered by antidumping.24 Thus, to the extent that international transactions occur between affiliates of the same multinational firm, exporters and importers have a shared incentive to keep markets free from new trade barriers.25 Global supply chains and a significant role of multinationals might therefore be expected to reduce antidumping activity, at least for countries and industries particularly prominent in global supply chains.

But there are additional channels through which the changing nature of global trade could also influence antidumping activity and its consequences. Antidumping may provide an important incentive for multinationals to substitute local subsidiary production in a foreign market for exports—that is, “antidumping-jumping” foreign direct investment (FDI).26 The important role of multinational firms in world trade also complicates the political economy of antidumping because it opens the door to new types of strategic behavior on the part of vertically integrated firms. Once a firm has established production in the former export market via FDI, its incentives with respect to antidumping or other trade barriers are likely to change. Trade barriers faced by other foreign suppliers can improve the firm’s own position relative to competitors that rely on arm’s-length transactions for imported inputs or that continue to serve the same market via exports. The firm may even increase its own exports from a foreign location in an attempt to trigger an antidumping investigation that will hamper competitors that lack local production capacity.27

The cases shown in table 2-2 illustrate the potential relevance of these issues for emerging markets. I conducted a search of the World Bank’s Temporary Trade Barriers Database for cases in which the same six-digit Harmonized System (HS-06) products and firm names were involved in antidumping investigations initiated in different countries (Bown 2016). Table 2-2 reports examples in which subsidiaries of the same multinational corporations have been involved in antidumping investigations over similar or related products in multiple emerging-market jurisdictions.

In the first example, the major tire-making multinational corporations Michelin, Bridgestone, Goodyear, and Pirelli all have subsidiaries involved either as petitioners or as targeted firms in antidumping investigations in emerging markets such as Turkey, South Africa, India, Thailand, Brazil, and China.28 In the second example, an Indian subsidiary of Osram (itself a subsidiary of the German multinational firm Siemens) was part of a petition for an Indian antidumping investigation of compact fluorescent lamps (CFLs) from China in which one of the targeted firms was Osram’s own subsidiary in China. In cases involving Owens Corning, Continental Carbon, Monsanto, and Graftech, the emerging-market subsidiary of a US-headquartered multinational firm initiated an antidumping investigation against imports from another emerging market. Moreover, not all these examples are of multinationals headquartered in high-income economies. In the last case, subsidiaries in India and Thailand of Indorama Synthetics, an Indonesia-headquartered multinational firm, were among supporters of antidumping investigations of yarn and fiber imports.

TABLE 2-2. Examples of Multinational Firm Overlap in Emerging Market Antidumping (AD) Investigations, 2000–2016

|

Firms (headquarters) |

Products (common HS code) |

Explanation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Michelin (France); Bridgestone (Japan); Goodyear (United States); Pirelli (Italy) |

Tires (401120) |

1. 2004: Bridgestone and Pirelli subsidiaries in Turkey are among petitioners for AD on tires from China (measures imposed in 2005). 2. 2005: Bridgestone and Goodyear subsidiaries in South Africa are among petitioners for AD on tires from China (no measures imposed). 3. 2005, 2008: Several Indian tire manufacturers (no apparent multinational firm affiliation) are petitioners for AD on bus and truck tires from China and Thailand (measures imposed in 2007 and 2010, respectively). Goodyear subsidiary in India played an inactive role in one investigation, supplying information to the Indian authorities but not actively supporting the investigation. First investigation targeted Bridgestone subsidiary in Thailand. Second investigation targeted Michelin subsidiaries in China and Thailand. 4. 2008: Bridgestone, Goodyear and Pirelli subsidiaries in Brazil are among petitioners for AD on truck tires from China (measures imposed in 2010). 5. 2013: Bridgestone, Goodyear, Michelin, and Pirelli subsidiaries in Brazil are among petitioners for AD on truck tires from Japan, Russia, South Africa, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand (measures imposed in 2014). |

||

|

Osram (Germany) |

Compact fluorescent lamps (853931, 853990) |

2007: Osram subsidiary in India is among petitioners for AD on compact fluorescent lamps from Osram subsidiary in China (measures imposed in 2009). |

||

|

Owens Corning (United States) |

Fiberglass (701912, 701931) |

1. 2003: Owens Corning subsidiary in South Africa petitions for AD on glass fibers from China (petition ultimately withdrawn). 2. 2006: Owens Corning subsidiary in South Africa petitions for AD on glass fibers from Brazil (petition ultimately withdrawn). One targeted firm in Brazil is the subsidiary of European glass fiber manufacturer Saint Gobain, which acquired the Owens Corning subsidiary in South Africa in 2007. 3. 2009: Owens Corning subsidiary in France is among petitioners for AD on glass fiber from China (measures imposed in 2011). 4. 2010: Owens Corning subsidiary in India is among petitioners for AD on glass fiber from China (measures imposed in 2011). |

||

|

Continental Carbon (United States) |

Carbon black (280300) |

1. 2008: Continental Carbon subsidiary in India is among petitioners for AD on carbon black from six countries including Australia. The main target in Australia is Continental Carbon Australia, a licensee of Continental Carbon Technology, though not a subsidiary (measures imposed in 2010). |

||

|

Monsanto (United States) |

Glyphosate herbicide (293100, 380830) |

1. 2001: Monsanto subsidiary in Australia petitions for AD on glyphosate from China (no measures imposed). 2. 2001: Monsanto subsidiary in Brazil is among petitioners for AD on glyphosate from China (measures imposed in 2003). 3. 2002: Monsanto subsidiary in Argentina petitions for AD on glyphosate from China (no measures imposed). |

||

|

Graftech (United States) |

Graphite (854511) |

1. 2003: Graftech subsidiary in Italy is among petitioners for AD on certain graphite from India (measures imposed in 2004). 2. 2008: Graftech subsidiary in Brazil petitions for antidumping measures on certain graphite from China (measures imposed in 2009). 3. 2010: Graftech subsidiary in Mexico petitions for AD on certain graphite from China (measures imposed in 2012). 4. 2014: Graftech subsidiary in South Africa petitions for AD on certain graphite from China and Pakistan (measures imposed in 2015). |

||

|

Indorama Synthetics (Indonesia) |

Yarns, fibers |

1. 2008: Yarn manufacturers in Brazil and Turkey are among petitioners for AD on yarn from Indorama Synthetics’ headquarters in Indonesia (measures imposed in 2009). 2. 2008: Indorama Synthetics subsidiary in India is among supporting petitioners for AD on yarn from China (targeting several firms not related to Indorama) and from an Indorama subsidiary in Thailand (measures imposed in 2009). 3. 2009: Indorama Synthetics’ headquarters in Indonesia is among petitioners for AD on polyester staple fiber from China (measures imposed in 2010). 4. 2013: Indorama Synthetics’ headquarters in Indonesia is among petitioners for AD on spin draw yarn, drawn textured yarn, and/or partially oriented yarn from China, Malaysia, South Korea, Taiwan, India, and Thailand (measures against Malaysia and Thailand imposed in 2015; no measures imposed against other exporters). |

||

|

Source: Constructed with data from Bown (2016) and updates. |

||||

|

Note: HS = Harmonized System. |

||||

Another reason to suspect that recent antidumping actions involving emerging economies may be enforcing rather than combating cartels is that some of these actions have targeted the same products that were identified in the links between antidumping use and cartel behavior in the 1980s and 1990s in high-income economies. Another search of the World Bank’s Temporary Trade Barriers Database looked for cases involving polyvinyl chloride (PVC)—one of the products related to the in-depth examination by Messerlin (1990) in the European Community context—or another industrial chemical, polyethylene terephthalate (PET). As illustrated in tables 2-3 and 2-4, in more than fifty different instances over the period 1995–2016, one or more of twelve G-20 economies initiated antidumping investigations into either PVC or PET products (Bown 2016). Some economies initiated multiple, sequential investigations and imposed new import restrictions against many foreign suppliers, including each other. However, it is also notable that the PVC and PET antidumping petitions described in these tables involved dozens of firms. Other things equal, participation of many more firms in the global market should make the formation and subsequent enforcement of a cartel in any of these sectors more difficult than it was in the 1980s and 1990s.

These examples of multimarket contacts among multinational firms indicate the possibility of policies such as antidumping being used to segment markets in relatively concentrated industries. However, we have no direct evidence indicating collusive behavior by the firms involved in any of the cases, and there are other plausible explanations for the patterns displayed. For example, the same foreign firm could have been dumping simultaneously across multiple jurisdictions, thus triggering the related antidumping filings. More broadly, certain products or even industries may have characteristics inherent to their production process, such as high fixed costs, or a market structure that “fits” the evidentiary criteria required for a viable antidumping case. But even the potential for collusive action calls for research based on detailed information on multinational firm linkages across countries, and perhaps also careful monitoring by antidumping authorities to ensure that their actions do not inadvertently promote anticompetitive outcomes.

TABLE 2-3. Antidumping (AD) Activity in the Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Market, 1999–2016

|

1. Argentina (2004, 2012) • Initiated AD in 2004 on Brazil, Korea, Taiwan (measures imposed on Brazil only in 2006) • Initiated AD in 2012 on China, India, South Korea, Taiwan, and Thailand (measures imposed in 2013) • Initiated AD in 2015 on Indonesia and USA (investigation on Indonesia ongoing; investigation on USA terminated in 2015) |

|

2. Brazil (2002, 2004, 2007, 2010) • Initiated AD in 2002 on India (no measures imposed) • Initiated AD in 2004 on Argentina, South Korea, Taiwan, USA (measures imposed on Argentina and USA in 2005) • Initiated AD in 2007 on India and Thailand (measures imposed in 2008) • Initiated AD in 2010 on Mexico, Turkey, United Arab Emirates (measures imposed in 2012) • Initiated AD in 2015 on China, India, and Indonesia (measures imposed in 2016) |

|

3. China (1999, 2001) • Initiated AD in 1999 on South Korea (measures imposed in 2000) • Initiated AD in 2001 on South Korea (measures imposed in 2003) |

|

4. EU (1999, 2000, 2003, 2009) • Initiated AD in 1999 on India, Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand (measures imposed in 2000) • Initiated AD in 2000 on India and South Korea (measures imposed in 2001) • Initiated AD in 2003 on Australia, China, Pakistan (measures imposed in 2004) • Initiated AD in 2009 on Iran, Pakistan, United Arab Emirates (measures imposed on Iran only in 2010) • Initiated AD in 2011 on Oman and Saudi Arabia (investigation withdrawn in 2011) |

|

5. South Korea (2007) • Initiated AD in 2007 on China and India (measures imposed in 2008) |

|

6. Turkey (2004) • Initiated AD in 2004 on China, India, Indonesia, South Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand (measures imposed in 2006) |

|

7. USA (2001, 2003, 2004, 2007, 2015) • Initiated AD in 2001 on India and Taiwan (measures imposed in 2002) • Initiated AD in 2003 on EU, Japan, South Korea (no final measures imposed) • Initiated AD in 2004 on India, Indonesia, Taiwan, Thailand (no final measures imposed) • Initiated AD in 2007 on Brazil, China, Thailand, United Arab Emirates (measures imposed in 2008, except on Thailand) • Initiated AD in 2015 on Canada, China, India, and Oman (measures imposed in 2016) |

|

8. South Africa (2005) • Initiated AD in 2005 on China, India, Indonesia, South Korea, Taiwan, Thailand (measures imposed on India, South Korea, and Taiwan in 2006) |

|

9. Japan (2017) • Initiated AD in 2016 on China (measures imposed in 2017) |

|

10. Indonesia (2012, 2016) • Initiated AD in 2012 on China, South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan (investigation terminated in 2014) • Initiated AD in 2016 on China, South Korea, and Malaysia (investigation ongoing) |

|

Source: Constructed with data from Bown (2016) and updates. |

The Rise of China and the Increasing Use of Export Restrictions

The importance of China as a dominant trader gives rise to additional issues relating to antidumping and how its use may be evolving in response to larger changes in the global economy. The first is associated with China’s sheer size, the second with China’s evident willingness and ability to use export restrictions in pursuit of its own policy objectives.

Even before its entry into the WTO in 2001, China had rapidly achieved a substantial share in the export markets of many industries, initially at the lower end of the technology spectrum (shoes and especially apparel) but increasingly in high-technology industries as well. In earlier decades, Japan’s rapid export growth similarly disrupted established trading patterns, and Japan became a primary target of antidumping and other TTBs. But in sharp contrast to the case of Japan, many Chinese firms are integrated into international value chains, either as subsidiaries of multinational firms or as contractors exporting inputs (such as auto parts) or processing and assembling imported intermediate inputs for export (such as computers). In a new trade pattern, some goods once exported directly by Japan to the United States and the European Union now arrive from China, but with much of their value in the form of inputs exported by Japan to China (Dean, Lovely, and Mora 2009). Because China plays such a large role in supply chains, aggressive trade policy measures on the part of the industrialized countries (still headquarters of most multinational firms) are less likely than in the earlier response to Japan’s rise as a major exporter.

TABLE 2-4. Antidumping (AD) Activity in the Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) Market, 1995–2016

|

1. Argentina (1999, 2012) • Initiated AD in 1999 on Mexico and USA (measures imposed in 2000) • Initiated AD in 2011 on USA (no measures imposed) • Initiated AD in 2012 on China and Germany (measures imposed in 2014) |

|

2. Australia (1996, 1997, 1999, 2001, 2012, 2014) • Initiated AD in 1996 on EU and South Korea (no final measures imposed) • Initiated AD in 1997 on EU, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, United Arab Emirates (no measures imposed) • Initiated AD in 1999 on EU, Indonesia, South Korea, Singapore (measures imposed in 2001, except on Indonesia) • Initiated AD in 2001 on EU, Indonesia, Israel, Norway, Taiwan (measures imposed on Israel only in 2002) • Initiated AD in 2012 on South Korea (measures imposed in 2012) • Initiated AD in 2014 on China (no final measures imposed) |

|

3. Brazil (1997, 1998, 2000, 2001, 2007) • Initiated AD in 1997 on EU and USA (measures imposed on USA only in 1998) • Initiated AD in 1998 on China and USA (measures imposed on China only in 1998) • Initiated AD in 2000 on EU and USA (no measures imposed) • Initiated AD in 2001 on Colombia, Japan, South Korea, North Korea, Thailand, Venezuela (no measures imposed) • Initiated AD in 2007 on China and South Korea (measures imposed in 2008) |

|

4. China (2002) • Initiated AD in 2002 on Japan, South Korea, Russia, Taiwan, USA (measures imposed in 2003) • Initiated AD in 2016 on Japan (preliminary measures imposed in 2017) |

|

5. India (2003, 2006, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2012) • Initiated AD in 2003 on EU, South Korea, Saudi Arabia (measures imposed on EU only in 2004) • Initiated AD in 2006 on China, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand, USA (measures imposed in 2008) • Initiated AD in 2008 on China and Taiwan (measures imposed in 2009) • Initiated AD in 2009 on China, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, Russia, Taiwan, Thailand (measures imposed in 2011 (except on Japan) • Initiated AD in 2010 on China (measures imposed in 2011) • Initiated AD in 2012 on EU and Mexico (measures imposed in 2014) • Initiated AD in 2014 on Mexico and Norway (measures imposed in 2015) |

|

6. South Korea (2004) • Initiated AD in 2004 on Japan (measures imposed in 2005) |

|

7. Turkey (2001, 2008) • Initiated AD in 2001 on EU, Israel, Russia, USA (measures imposed in 2003, except on Russia) • Initiated AD in 2008 on China and Vietnam (measures imposed in 2008) |

|

8. USA (1995, 2002) • Initiated AD in 1995 on EU (no measures imposed) • Initiated AD in 2002 on China (no final measures imposed) |

|

9. South Africa (1996, 2000, 2007) • Initiated AD in 1996 on Brazil, Canada, China, EU, Japan, North Korea, Taiwan, USA (measures imposed on Brazil, China, EU, and USA in 1997) • Initiated AD in 2000 on EU, India, South Korea, Thailand (measures imposed in 2001) • Initiated AD in 2007 on China and Taiwan (measures imposed in 2008) |

|

Source: Constructed with data from Bown (2016) and updates. |

Another potential advantage China enjoys is the size of its economy. For industries where scale economies are important, China is far better positioned than earlier superexporters to bring down production costs by capturing these economies. As China becomes an important supplier of higher-technology goods and services, the large scale of its total production for both domestic sale and export offers an unprecedented opportunity to spread fixed costs, including the costs of research and development.29

The advantages due to China’s size as a producer and exporter are complemented by China’s status as a transition economy. Though the role of market forces in domestic resource allocation and trade has been increasing, the role of government at all levels remains important in many ways, ranging from terms on which firms are able to obtain capital to export incentives and restrictions. Although every country exercises industrial policy to some degree, it seems fair to say that top-down control over economic activity is still much more extensive in China than in most of the markets to which it exports. This is highly significant because of the possibility that dumping that can harm an importing country’s overall economic well-being (that is, in situations in which gains to consumers do not outweigh losses to import-competing producers); the relative size and concentration of the export supply is important. To be profitable for exporters, both predatory and strategic dumping require the relevant exporters to have a substantial market share in the import-competing country and also that export supply is sufficiently concentrated to allow coordinated action by exporters once dumping has eliminated domestic import competition. Even in what would appear from the perspective of an outsider to be relatively competitive Chinese markets—with dozens or even hundreds of exporting firms—in diverse sectors including textiles and apparel and raw materials and rare earths, Chinese officials have demonstrated their ability to limit total exports to achieve policy objectives.30 Although many other countries have also restricted their own exports for a variety of reasons, it is the unique combination of China’s importance as an exporter and its willingness to curtail supply that makes the situation particularly conducive to predation in countries that import its products.

CONCLUSIONS

Over a century, antidumping has gradually evolved from an obscure and rarely used policy tool to one that now constitutes an important form of protection not subject to the same WTO controls as members’ bound tariff rates. Rather, antidumping is one of several instruments that allow members to exceed their bound tariffs, albeit subject to very detailed WTO procedural disciplines.31 Moreover, while the application of antidumping was until the WTO era mainly the province of a few traditional users, emerging markets have become some of the most active users of antidumping and related policies, as well as important targets of their application. And though these policies are known collectively as temporary trade barriers, WTO rules governing the duration of antidumping measures are much weaker than for safeguards.

As antidumping use has evolved and proliferated (about fifty countries now have antidumping statutes, although some are not active users), both its economic justification and the concerns raised by its possible abuse have also evolved. While the original justification of antidumping was to protect importing countries from predation by foreign suppliers, by the 1980s antidumping had come to be regarded as just another tool in the protectionist arsenal. Even more worrying, evidence began to mount that antidumping was being used in ways that actually enforced collusion and cartel arrangements rather than attacking anticompetitive behavior.

Today’s world economy and international trading system are much different even from those of the early 1990s, when this concern reached its peak. Some changes, in particular the significant growth in the number of countries and firms actively engaged in international trade, tend to limit the possibility of predation by exporters. Moreover, antidumping has developed a political-economic justification as a tool that can help countries manage the internal stresses associated with openness. But other changes, especially the important role of multinational firms and intrafirm trade and the increased use by many countries of policies to limit exports, suggest that concerns about anticompetitive behavior by exporters cannot be entirely dismissed. Vigilance to ensure that antidumping is not abused by complainants to achieve and exploit market power thus remains appropriate today.

NOTES

I dedicate this paper to Rachel McCulloch—my longtime mentor, colleague, co-coauthor, and friend—who worked on an earlier draft before her passing in 2016. Thanks to Aksel Erbahar and Eva Zhang for outstanding research assistance and to Bernard Hoekman, Patrick Messerlin, Simon Evenett, Mike Finger, and participants at the conference “21st Century Trade Policy: Back to the Past?” conference at the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization for useful comments. Any remaining errors are my own.

1. The economic literature on antidumping is vast, and I have not attempted a comprehensive review. Nelson and Vandenbussche (2005) offer a two-volume selection of 47 significant contributions, including some of the classic references cited below. See also Blonigen and Prusa (2016).

2. Another WTO-legal means of increasing protection unilaterally is available to most emerging economies, whose bound tariff rates (the maximum rates to which a country has committed) typically exceed the currently applied tariff rates by a comfortable margin. It is still an open research question why many countries choose to use antidumping, safeguards, and other temporary trade barriers rather than simply raising applied tariffs when they have the legal right to do so. For example, an empirical study by Gawande, Hoekman, and Cui (2015) examines determinants of the trade policy responses of seven large emerging market countries to the 2008–2009 global crisis. While all except China had average applied tariff rates well below their WTO bound rates, these countries made only limited use of the resulting “policy space” for unilateral tariff increases. The authors find support for several factors that might be expected to moderate pressure for increased protection, including participation of domestic firms in global supply chains.

3. Of course, WTO-legal safeguard protection was designed to address exactly this type of situation. However, antidumping enjoys several advantages from the viewpoint of an import-affected industry. Because dumping is considered an “unfair” trade practice, the injury requirement is less stringent than for a safeguards case. Furthermore, antidumping protection does not require compensation of foreign exporters and has no definite time limit on its application. Moreover, antidumping is inherently discriminatory, so restrictive measures can be applied only to some countries or even to some specific firms and not others. Often importers focus antidumping on new suppliers whose exports threaten the position of established foreign sources. Finally, unlike safeguards, antidumping is not typically subject to any final check from the head of state, who may decline new protection for a variety of reasons, including effects on consumers or relationships with trading partners.

4. For the United States in the period 1997–2006, Bown and Crowley (2013) find evidence consistent with the theory that antidumping and safeguards are used in response to the sorts of economic shocks and incentives modeled by Bagwell and Staiger’s (1990) theory of cooperative trade agreements. Bown and Tovar (2011) find that India used antidumping and safeguard protection in the late 1990s and early 2000s to reverse much of the tariff reform carried out as part of its 1991–1992 International Monetary Fund program. This finding is consistent with the political-economy justification of antidumping—that is, the same domestic political pressures that led to higher ex ante tariffs in particular sectors were later accommodated through antidumping protection.

5. However, Moore and Zanardi (2009) reach a contrary conclusion. They use data for a sample of twenty-three developing countries, including some that have become aggressive users of antidumping, to examine whether use of antidumping has contributed to tariff reductions. Their results do not support the “safety valve” argument that the availability of antidumping encourages countries to liberalize. In fact, use of antidumping may have led to less rather than more liberalization, at least for countries in their sample.

6. Using a sample of forty-one countries that adopted antidumping laws after 1980, Vandenbussche and Zanardi find evidence of what they call a substantial “chilling effect” averaging 5.9 percent for five “tough new users” in their sample—a significant offset to the increased trade due to liberalization and a figure much larger than the share of trade directly affected by temporary trade barriers (Bown 2011a). But Finger (2010) disputes the authors’ characterization of the trade effects of antidumping as “too large to be dismissed as a ‘small price to pay’ for further liberalization” because Vandenbussche and Zanardi offer no evidence that the same overall liberalization could have been maintained at lower cost through alternate means. In fact, their own results indicate a high ratio of increased aggregate trade to trade lost through backsliding via antidumping—for example, six for Brazil and ten for Turkey. See also Egger and Nelson (2011).

7. National antidumping statutes vary, and some at least leave room for authorities to consider effects on consumers as well as producers. In practice, however, producers’ interests are paramount in determining outcomes even where there is legal scope to do otherwise (Messerlin 1994).

8. For additional discussion of strategic dumping, see Messerlin 1994; Willig 1998; and Mavroidis, Messerlin, and Wauters 2008, 17–19.

9. Potential benefits from scale economies may be internal or external to the firm. Static internal scale economies may result from high fixed costs of production. Dynamic external scale economies may result from learning by doing, where one firm’s improved production techniques may be quickly transmitted to other producers as workers move between firms. Even when improved technologies are protected by patents or trade secrets, competing firms usually benefit to some degree because innovating firms are not able to capture all the benefits.

10. Here country size offers a rough approximation to the domestic size of the relevant industry and thus the potential for gains through scale economies. However, industry size also depends on level of development, as measured, for example, by GDP per capita. Moreover, the industry may also serve other markets through exports or local subsidiary production. In particular, if scale economies are internal to the firm, as with a large fixed cost of research and development required by a particular product, a multinational firm will derive scale economies from its global production because the fixed costs can be spread over production in multiple locations.

11. Although supporters of aggressive antidumping enforcement often cite the sanctuary market hypothesis, preliminary empirical results reported by Moore (2015) cast some doubt on its practical relevance, at least for US firms facing antidumping actions abroad. Moore examines cases of US companies facing frequent antidumping actions and finds no evidence that their export success arose from a protected home market. Rather, antidumping actions typically target successful exporters and ones from capital-intensive industries like steel, chemicals, and plastics, where fixed costs are high. Steel products are also among the foreign exports most often targeted by US antidumping and other temporary trade barriers.

12. When demand falls, a competitive firm with fixed costs maximizes profits (that is, minimizes losses) at the output where market price is equal to marginal cost, as long as marginal cost is at least equal to the average variable cost of production. When the market price is too low to cover all costs of production, an exporting firm following this strategy is dumping. Irwin finds no evidence that the Japanese export price was less than marginal cost.

13. Similarly, soon after the United States imposed antidumping duties on flat-panel displays in 1991, Toshiba, Sharp, and Apple announced plans to shift assembly operations abroad (Irwin 2005b, 77–78).

14. Durling and Prusa (2003) note that raising rivals’ costs is well known in the industrial organization literature as a strategy by which a dominant firm can limit supply from competitors. They make the case that import protection can be used in exactly this way. Although they focus on the effects of the US steel safeguard action of 2002, the same logic applies to any kind of protection that increases the cost of imported inputs. Also see Messerlin (1994).

15. “Strategic” behavior here refers to firms taking account of interactions between their own behavior and that of their rivals, as well as possible responses by trade authorities. See, for example, Staiger and Wolak (1989, 1992). In contrast, strategic dumping refers specifically to a firm’s export sales at an artificially low price that are motivated by potential gains from increasing the scale of its production.

16. WTO rules restrict the use of voluntary export restraints, which were common before the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations. However, the WTO still permits use of price undertakings (price floors) to settle antidumping cases. As Moore (2005) shows, the two policies have identical effects under perfect competition, but the results differ when firms have market power.

17. Johnson and Sweet (2012); Sweet (2012). Duties ranged from 31 percent to nearly 250 percent. This antidumping duty was on top of a countervailing duty of 3 percent to 5 percent levied in March. The initial antidumping duties were followed by a second round of duties against China and Taiwan in 2014. When trade diversion continued from new third countries, the US industry then requested a global safeguard, which resulted in comprehensive import restrictions imposed in 2018.

18. Crowley, Meng, and Song (2019) provide an empirical assessment of the European Commission’s antidumping case against Chinese solar panel producing firms and its impact on stock prices.

19. Japanese exports of color television sets and other consumer electronics in the 1980s provide an interesting parallel. Japan did create an export cartel that limited total sales to the United States at a price below that charged at home (classic dumping in the form of price discrimination). But while US production was indeed squeezed out by imports from Japan and other countries, prices of the imports continued to fall while quality continued to rise. Thus there is no evidence of successful predation, even if predation had been the original intent of Japan’s Ministry of International Trade and Industry.

20. While most of the TTB use consists of antidumping measures, some countries (such as Turkey, India) have been increasing their use of relatively substitutable policies such as safeguards (Bown 2013).

21. Bown (2013, 2018) provides a detailed empirical assessment of use over time of antidumping and related TTBs to target exports of emerging economies.

22. Messerlin (2004) provides an early analysis of the emergence of China as a user of antidumping.

23. In their study of the determinants of intra-firm trade, Bernard and others (2010) report that 46 percent of total US imports in 2000 occurred between related parties. The importance of intrafirm transactions varied significantly by trading partner, ranging from close to zero to nearly 100 percent, and also by product.

24. Krupp and Skeath (2002) provide empirical evidence of a negative impact on production by downstream users of intermediate products subject to antidumping duties. The authors use a panel of thirteen upstream/downstream product pairs—such as methanol and formaldehyde—for the period 1977–92 to identify the effects of antidumping duties in the upstream industry on production and sales in the downstream industry. Antidumping duties upstream are confirmed to have a negative effect on downstream production. However, the authors do not find a significant negative effect on downstream value, perhaps because the direction of the effect on total revenue of lower quantity supplied depends on the elasticity of demand for the downstream product. A challenge for this type of research is finding upstream products tied significantly to specific downstream activities. Results are likely weaker to the extent that downstream producers have access to good substitutes for the input affected by antidumping.

25. Gawande, Hoekman, and Cui (2015) find evidence for seven large emerging market economies that participation in global supply chains helped to keep protectionism in check during the 2008–2009 global crisis.

26. An important early example of the relationship between administered protection and foreign direct investment came in the voluntary export restraint (VER) agreement negotiated between the United States and Japan in autos in 1981. In their support for protection, an explicit goal of the United Auto Workers was to encourage Japanese companies to establish factories in the United States. Likewise, although the gap left by European VERs on Japanese autos was initially filled by traditional European suppliers in Italy and Germany (De Melo and Messerlin 1988), VER-jumping Japanese FDI soon followed. On antidumping-jumping FDI, see Blonigen (2002). Washing machines are a recent US example in which imports from South Korean firms (Samsung and LG) were hit first with antidumping, then with a global safeguard after the firms moved production to third countries. Each has also increased production in the United States that will allow them to avoid the tariffs (see Bown and Keynes 2018).

27. Blonigen and Ohno (1998) provide a theoretical model of “protection-building trade” in which foreign-headquartered firms locate production in the home country and then increase their own exports to the home country so as to increase protectionist pressures that would result in higher barriers against other foreign competitors in the future.

28. According to industry reports, Michelin, Bridgestone, Goodyear, and Continental together accounted for almost 55 percent of the world market in 2010 (Datamonitor 2011, 13). Michelin, Bridgestone, Goodyear, and Pirelli each have subsidiaries in many emerging markets, including China, the latter often through joint ventures. Not included in the table is the US 2009 China-specific safeguard tariff on tire imports, a case that was not brought by the US domestic tire producers—that is, US-headquartered firms or US affiliates of foreign-headquartered multinationals—but by the United Steelworkers on behalf of the industry’s unionized labor force.