4

CHINA AND THE WORLD TRADING SYSTEM

WILL “IN AND UP” BE REPLACED BY “DOWN AND OUT”?

L. ALAN WINTERS

This chapter examines the integration of China into the world trading system. It discusses the size and nature of the shocks that it administered to the world economy and some of the reactions to those shocks proposed by policymakers and academics. From its awakening in 1978, China was welcomed into the global economy and generated a huge boost in output and incomes—the “in and up” referred to in the title. More recently, however, concerns have been expressed about the health of the Chinese economy, and steps have also been taken to curtail its trade, both by excluding it from the major trade initiatives that we have come to term the “megaregionals” and through the direct imposition of trade sanctions by the United States—the “down and out.” It is too early to predict the outcome of the latter phenomenon, but it is important to understand some of the history and causes of China’s integration in order to reduce the chances of policy running into disaster down a blind alley.

It is a great pleasure to honor Patrick Messerlin in this chapter. Patrick has been one of the foremost exponents of applied trade policy analysis and advice over several decades, with an unfailing focus on the key issues of the day. I argue that integrating China into the global economy in a way that benefits nearly all presents perhaps the most important international trade and trade policy issue of our present era, and so it is no surprise that it is one that Patrick has also addressed.

This chapter argues that the shock that the emergence of China is administering to the world economy is larger than any seen previously—and by a large margin. The shock has many manifestations, but here, in line with Patrick’s great expertise, I focus on its effects on and through the world trading system. I suggest that, although the huge increase in global production that the success of China brings has produced widespread benefits, there will inevitably be some stresses and indeed possibly some losers. Some of these stresses are essentially microeconomic—competitive pressure on firms elsewhere in the world—while another set arises from the macroeconomic imbalances that China’s rapid growth has induced globally. Part of China’s integration into the global economy entailed joining the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, and it has become a forum in which many of the stresses just noted have been debated: I note that China has adapted almost completely to the standard forms of behavior within the WTO despite suffering from a number of asymmetries in treatment by other members. One potential asymmetry that has mercifully been put on the backburner for now is to bring exchange rates within the purview of the WTO with a view to punishing China’s alleged undervaluation of its currency. But it was followed by another in the form of the megaregional trade deals—notably the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)—that I argue were designed to exclude China; and as that receded, a third emerged in the form of the Trump administration’s hostile trade (and other) policies toward China.

Possibly the most important role of economists in policymaking—and one that characterizes significant parts of Patrick Messerlin’s career—is to discourage policymakers’ instincts to react to challenges inappropriately. At least until recently, most of the challenges that China has posed within the trading system have eventually been dealt with constructively, which is something both Chinese and Western governments can take some credit for. However, it is not a given that this pattern will persist.

THE MACROECONOMIC SHOCK

In the three decades following the Communist Revolution in 1949, China displayed a respectable but by no means spectacular rate of economic growth. Maddison (2007, table 2.2b) suggests that, after an initial fall, the growth in Chinese gross domestic product (GDP) was 4.4 percent per year over the period 1952–1978, with growth in GDP per capita at 2.3 percent; this growth was associated with a strong reorientation from agriculture to industry. Over this period, China increased its share of world GDP from 4.6 percent to 4.9 percent. Arguably more important from our point of view, however, is that over the preceding two hundred years China had played little role in the world economy and that the decades of Communism did nothing to redress this. In 1950, China exported goods worth $11.6 per capita of population at 1990 prices (compared with war-torn Japan’s $42.21) and by 1973 this had grown to $13.26 (compared to Japan’s $874.87) (Maddison 2007, table 2.4). So far as international economics was concerned, China barely existed.

In 1978, China took the first tentative steps toward opening up, first internally, with the household responsibility system, and then gradually externally. The outlines of the rest of the story are well known: China’s GDP and exports, and even its imports, grew phenomenally. Table 4-1 summarizes the situation starting from 1981, the approximate point at which it had discernible effects on the rest of the world.

Rows 2 and 3 of the table show China maintaining aggregate growth of 10 percent per year for nearly four decades, whether in (constant) market prices or international prices (purchasing power parity). Moreover, China managed more successfully than other developing countries to control population growth (see row 1) with the result that income per head increased by 9 percent annually. Such strong growth is not wholly unprecedented; Korea, Taiwan, and Japan all showed similar trends for at least two decades (see Winters and Yusuf 2007). But two features are unprecedented: first, the differential between the supergrower’s growth rates and that of the world economy during their growth phases (Winters and Yusuf 2007, table 1.2), and second, the combination of rapid growth and huge size. Table 4-2, which is partly inspired by a slide from McKinsey, makes the point powerfully. While it took Britain, as the only industrial country in the eighteenth century, 155 years to double income per head from the boundary of extreme poverty to well into middle-income territory, it took the United States and Germany about sixty years in the nineteenth century, Japan thirty-three years in the early twentieth century, and China twelve years in the later twentieth century. And while the first four countries represented no more than 2.6 percent of the world’s population at the start of their growth spurts, China had more than 20 percent of the population.

TABLE 4-1. China’s Growth, 1981–2017

|

1981 |

2017 |

Growth per year (%) |

||||

|

Population (billions) |

0.994 |

1.386 |

1.0 |

|||

|

GDP (billions of constant 2005 US$)a |

228 |

5.274 |

10.0 |

|||

|

GDP, PPPb (billions of constant 2011 international $) |

746 |

21,224 |

10.7 |

|||

|

GDP per capita, PPP (constant 2011 international $) |

750 |

15,309 |

9.6 |

|||

|

Source: World Development Indicators Online, March 7, 2019. |

||||||

|

a GDP in constant prices was collected directly until 2014 and extrapolated using data in 2010 dollars from there. |

||||||

|

b PPP = purchasing power parity. The PPP data for 1981 were estimated from data on a 2005 price basis and the conversion factors implied between the 2011 and 2005 bases. Both were collected from WDI Online in June 2011. |

||||||

Growth of the magnitude that China has generated affects global equilibriums in many areas such as the UN Security Council and the International Court of Justice, as well as simple economic ones. However, so far as other countries are concerned, those pertaining to the world trading system are the most immediate, direct, and visible and quite possibly the most important. For example, exploding levels of international trade were a key contributor to China’s successful growth model, and also to the aggregate levels of international trade, growth, and prosperity elsewhere. And booming trade has also underpinned other aspects of China’s international economic relations that have also proved contentious—for example, its aid policies and its massive levels of reserves and consequent role in international finance.

China’s enormous appetite for natural resources, including food and energy, affects prices and availability elsewhere and raises incentives for production and investment in these international industries, regardless of whether they are used to produce goods for China’s own consumption or that of others. All international trade has distributional effects—which is why it is so contentious—but the introduction of a huge supplier at the labor-intensive end of the spectrum of comparative advantage has had profound competitive effects on other labor-abundant countries, and these effects are gradually starting to spread to other countries as China develops other skills and comparative advantages. Moreover, the large production that China has made available has driven down prices for consumers, especially the poorer ones who purchase less sophisticated varieties (Broda and Weinstein 2009).

The trade link also has institutional form in the shape of the WTO. While accession to the WTO must have boosted China’s growth and integration, it correspondingly means that if anything did go wrong, the WTO would be damaged with a consequent loss of the other functions it plays in the world economy such as settling disputes, transmitting information, and smoothing relations between other pairs of countries.

TABLE 4-3. China’s Changing International Trade, 1981–2017

|

1981 |

2017 |

Growth per year (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Exports (billions of $) |

14.6 |

2,418 |

15.3 |

|||

|

Imports (billions of $) |

14.6 |

2,208 |

15.0 |

|||

|

Fuels and ores as a percentage of: |

||||||

|

Imports |

6.0a |

25.9 |

||||

|

Exports |

25.2a |

2.7 |

||||

|

Reserves (billions of $) |

10.1 |

3,236 |

17.4 |

|||

|

as a percentage of annual imports |

69 |

147 |

||||

|

Source: World Development Indicators Online, March 7, 2019. |

||||||

|

a Refers to 1984, not 1981. |

||||||

The changes in China’s international trade are proportionately even larger than those in aggregate income shown in table 4-2. Table 4-3 shows that the growth of Chinese exports and imports averaged over 15 percent for nearly four decades and that of foreign exchange reserves over 17 percent. These reserves covered eight months of imports in 1981, at which point Chinese trade was more or less balanced; by 2014 the reserves had increased to cover nearly two years’ worth of imports, and exports exceeded imports by about 20 percent. Moreover, China has shifted from being a net exporter of industrial raw materials to being a massive net importer. Since 2014, China’s trade imbalance and accumulation of reserves have declined somewhat.

THE MICROECONOMIC SHOCK FOR MANUFACTURERS

Given the size of the macroeconomic turnaround just outlined, it is not surprising that some sectors faced significant pressure and adjustment as a result of the emergence of China as a major manufacturer. I illustrate this pressure from three separate perspectives. First, Wood and Mayer (2009) consider the effect of China’s arrival on global factor endowments and on the resulting changes in other countries’ comparative advantage. While the emergence of China obviously contributed some land, capital, and skilled labor to the world’s endowments of factors of production, its principal and disproportionately large contribution was in unskilled labor. Wood and Mayer estimate that it raised the global ratio of labor with basic education to all labor by 7 to 9 percent and reduced the ratio of land + natural resources to all labor by 10 to 17 percent.1 The authors say that neither of these impacts was either vast or trivial. I doubt if any such shock had been experienced over a period as short as two decades.

The consequence of these changes in the global aggregates was that many countries that had previously been able to trade as unskilled labor-abundant countries now found themselves outside that class and having to behave instead as abundant in (middle-level) skills or in natural resources. The resulting adjustments, compressed into so short a period, were potentially quite dramatic. Applying a Heckscher-Ohlin model of world trade in which capital flows freely and hence may be ignored, Wood and Mayer calculate that these changes in endowments meant that on average other countries reduced the ratio of labor-intensive manufactures to primary production by 7 to 10 percent for output and 10 to 15 percent for exports. In East Asia, which had long appeared to be the most labor-abundant region, these developments caused significant deindustrialization. Elsewhere, Wood and Mayer argue, they were quantitatively less significant, although they did still have an effect.

The second and third exercises to identify competitive pressure concern competition between Mexican and Chinese producers, most of which, I argue, takes place in the US market. As a middle-income producer of relatively labor-intensive manufactures, Mexico might be thought to be particularly vulnerable to competition from China, especially given that within the North American preferential trade bloc, Mexico has a specific comparative advantage in such sectors. Moreover the focus on third-country markets as the locus of competition provides an important policy perspective, for even if Mexico chose to protect its own market from Chinese competition, it cannot unilaterally do so in the third markets in which the two suppliers meet.

In the second exercise, reported fully by Iacovone, Rauch, and Winters (2013), we look at the effect of Chinese competition on the survival chances and sales of Mexican firms both at home and in the United States. The sample comprises plant-level data for nearly all Mexican manufacturers (data on some small firms are missing) over the period 1994–2004. Over six thousand plants are covered and nearly three thousand individual products. As well as considering competition in a third market, the other innovation of this work is to allow the effects of competition to vary by firms with plant size and product—with the importance of a product in its plant’s total output.

The results are consistent and stark. While competition from China (measured as China’s share of Mexican or US imports of the product concerned) seems to hit smaller plants and minor products quite hard, it has relatively little impact on plants’ main products or on the largest plants. In line with other literature on firms, one can take size as a good proxy for productivity, so the conclusion is that competition tends to drive weaker plants and products either out of business or to contract, while leaving stronger ones either unaffected or even able to expand.

FIGURE 4-1. The Effect of Chinese Competition on Product Sales and Exit, 1994–2004

Source: Reproduced from Iacovone, Rausch and Winters (2013), figure 3.

Figure 4-1 summarizes Iacovone, Rauch, and Winters’s (2013) results for products. Similar patterns are uncovered at the level of the plant. The horizontal axis reports product size (position in the ranking of plants—centiles) and the vertical axis the marginal effect of an increase in Chinese competition on plant sales in Mexico (domestic) and the United States (exports) in the left-hand block and the marginal effect on the probability of the products being withdrawn from sale completely (exit) in the right-hand block. For small products (where, say, they account for 10 percent of a plant’s total sales) the effect on sales is strongly negative—a 1 percent increase in competition leading to a 0.4 percent decline in Mexican sales, whereas for products at the 90th centile, the effect on sales is positive—approximately 0.1 percent for export sales and approximately 0.3 percent for domestic sales. The broken lines are 95 percent confidence intervals and so one can see that the latter effect is significantly positive. Turning to exit on the right, the story is the same. For small products (10th centile) the effect of a 1 percent increase in Chinese competition is to increase the probability of exit from the export market by about 0.1 percent and from the home market by about 0.5 percent. For large plants, competition reduces the probability of exit—that is, it is associated with an increase in the chances of survival. We cannot identify the precise mechanism at work here, but it may well be that as Chinese competition eliminates weaker firms, sector-specific factors of production are released for stronger firms to take on.2

The stress is plain here. While Chinese competition may be a constructive force for the long-run growth of productivity and incomes—it helps to eliminate the weak and boost the strong—it is a political nightmare in distributional terms in most countries and is likely to raise serious calls for the management or even curtailment of trade. Giving in to this will mean benefits forgone in both China and its trading partners.

The final evidence of competitive pressure shows how Chinese competition constrains the export prices of Mexican producers in the US market. Pang and Winters (2012) use data at the six-digit level of the Harmonized System classification between 1992 and 2008 to show that on average changes in Chinese prices on the US market induce changes in Mexican prices in the same direction and of a little under half the size.3 Chinese pricing has been very competitive over this period driven by China’s strongly increasing productivity: for example, Hsieh and Ossa (2016) suggest that productivity growth in Chinese manufacturing sectors ranged from 7.4 percent to 24.3 percent and averaged 13.8 percent over the period 1995–2007. Thus while Chinese producers have been able keep prices down because their costs are falling, Mexican producers have felt obliged to follow suit partially; but with weaker productivity growth, they have seen their margins squeezed. These results are consistent with the previous ones of exit and declining sales, but may also be partly additional to them. Iacovone, Rauch, and Winters did not have data on margins, and so it is perfectly possible that even though Mexican firms stayed in business, they did so with weaker margins and hence lower value added.

These last results also cast light on a further cause of concern that has been expressed about China—“exporting deflation.” Much of this argument is of a macro nature, which I will deal with later, but if it is to be taken literally as placing downward pressure on prices, the mechanism must be as I have described here. A number of scholars have tried to identify the effect of Chinese growth on aggregate prices by relating prices in the United States or other developed countries to the quantity of Chinese exports (see, e.g., Kamin, Marazzi and Schindler 2006). Such attempts have largely failed and led to the conclusion that China is not exporting deflation (Broda and Weinstein 2010). Part of the problem is that despite China’s large size and openness, goods from China still account for only around 3 percent of US expenditure, and hence can have only a tiny direct influence on US aggregate price indices. If China is to have a discernible effect on such indices, it has to be by influencing the prices at which other producers sell, and this is the issue that Pang and Winters (2012) tackle directly.

More recently there has been an influential literature on the effects of Chinese trade on local economies in the United States—see, for example, Autor and others (2014) and related works. These have argued that imports from China have had a persistent negative effect on employment and welfare in the localities that produced goods in most direct competition with China, and also some aggregate employment effects as well. While the hardships that Autor and colleagues identify are real enough and clearly pose a challenge to the neoclassical view of smoothly adjusting economies, it is important to remember that they do not undertake a full welfare evaluation. For that one needs to consider the advantages of lower prices for consumers (Broda and Weinstein 2010) and the collateral benefits that accrue to US exporters (Feenstra and Sasahara 2018).

These results do indeed suggest that China contributed to the “Great Moderation” whereby Western economies seemed more or less to have abolished inflation, despite operating at high levels of capacity utilization and stoking up a huge credit boom. They are also, however, eminently reversible, and although current preoccupations with China are more to do with China exporting deflation via declining demand and output (see next section), when these cyclical phenomena have worked themselves out I would expect China to exercise very much less downward pressure on Western prices.

CHINA AND THE WTO

The World Trade Organization has rightly sought a global membership, and welcoming China in late 2001 was perhaps the biggest and most natural recent step toward that goal. China’s accession has been analyzed extensively—including by Patrick Messerlin himself—and I shall consider only three aspects of it: China’s behavior as an active member of the WTO, the criticisms of China’s role in the ongoing Doha Round, and the recent escalation of tariff hostilities between the United States and China.

There was some interest—and concern in some quarters—as to how China would settle into the WTO institutionally. China has not had a great enthusiasm for joining organizations in which it played no formative role, and the question arose whether China would behave as “regular club member,” be disruptive, or just remain aloof. After eighteen years we can say with confidence that China has become a “regular member,” pursuing, like other members, what it perceives as its own interests within the context of existing WTO rules and practices. Of course, other members have not always been comfortable with China’s actions, and some have accused China of violating the spirit if not the letter of WTO rules. However, while there are clearly issues to be addressed and a strong case for extending and making WTO rules more explicit, it does not seem to me that China has behaved fundamentally differently from other large members.

For example, China has played an active role in the achievement of transparency within the WTO. As Collins-Williams and Wolfe (2010) have observed, over the period to 2006–2008, China made over 500 notifications on product standards to the WTO Committee on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT), was active in the Subsidies and Countervailing Measures Committee, and even participated in the Agriculture Committee. China has also been heavily involved in the WTO’s dispute settlement procedures. It has more often been respondent than plaintiff, but the surprising figure is the frequency with which it has taken third-party status—observing and making minor contributions to cases primarily involving other members. Most commentators see this last phenomenon as a conscious learning strategy by which China sought to develop the skills and experience necessary to handle its own cases successfully.

Hsieh (2010) argues that China’s lack of legal capacity has been a major constraint on its ability to pursue WTO disputes independently and may have led it to fare less well in the cases it has been involved in. As with so many issues that it identifies, China has set about redressing the lack of skills vigorously. WTO Centers were set up in several universities, and Chinese scholars are increasingly active in academic and policy debate around trade policy and the trading system. Patrick Messerlin has greatly aided this learning process himself, by fostering links and forums in which Chinese and other commentators can meet.

Kennedy (2012) offers a detailed account of China’s engagement in WTO disputes. He concludes that China has been playing the role of a “system maintainer” by conforming to the practices of WTO dispute settlement, even as those practices develop. China has mainly used the system to challenge the differentiated treatment of its exports meted out by its two largest trading partners, the United States and the European Union, at least some of which stems from what the Chinese consider to be an asymmetric and unfair Protocol of Accession. Kennedy argues that the cases that China has initiated arise largely in retaliation to occasions in which it felt that a particular partner was initiating “too many” cases against China; that they were, perhaps, “warning shots” about the problems that an uncooperative China could cause. Such retaliation is by no means unique to China. Moreover, China has never initiated a case against a developing country, even those that have participated in cases against China. Hence, overall, fears that China would disrupt the WTO’s enforcement function have not materialized.

Two specific asymmetries irked the Chinese in particular: nonmarket treatment and export restraints. On the former, the EU and the United States denied China market economy status in antidumping cases, which increased both the frequency and the severity with which they claimed to find dumping. Nonmarket treatment was due to cease in 2016 according to the Protocol of Accession, but in the EU case the cessation was substantially nullified by modifications to the general rules for the application of antidumping duties and an official handbook helping EU firms to identify and bring cases against alleged dumping. Critically, however, on its face this development eliminated the discrimination felt by China.

The second asymmetry that caused upset was that China is more constrained from imposing export restrictions than are other WTO members. Within the mercantilist mindset that conditions the structure and practice of the WTO, consciously restraining exports is almost inconceivable and faces very few constraints in the WTO agreements: quantitative export restrictions are generally discouraged, but export taxes remain entirely unconstrained for all but a few recently acceded countries. China is among these, having been required to commit to using export taxes on only eighty-four products that were listed in its Protocol of Accession.

Every past GATT/WTO dispute concerning export restrictions has revolved around the accusation that a member has been reducing the price of an input to downstream producers and so enhancing its competitiveness unfairly (a mercantilist argument). And, at least in some cases, there has been a subtheme that the policy involved has increased prices abroad. China has now been involved in two such cases—a dispute brought in 2009 over export taxes and quantitative restrictions on exports of bauxite, coke, fluorspar, magnesium, manganese, phosphate (yellow phosphorus), silicon (metal and carbide), and zinc, and one brought in 2012 on exports of so-called rare earths, tungsten and molybdenum. Both concluded with rulings that rejected nearly every argument put forth by the Chinese, and in particular rejected claims that the export restrictions were necessary in order to prevent environmental damage and conserve resources (GATT Article XX (paragraphs (b) and (g) respectively). The problem for the Chinese in both cases was that domestic use of the minerals in question was increasing and domestic prices were lower at the same time that exports were being curtailed, although in the rare earths case these conditions largely disappeared soon after the case commenced.4

Chinese irritation was redoubled in the rare earths case by the dispute panel and the Appellate Body of the WTO finding that even if export restrictions were necessary to conserve rare earth resources, the Chinese did not have access to Article XX of the GATT, which recognizes this as a potentially legitimate reason to control exports. This is because the article in the Protocol of Accession that deals with export restraints did not explicitly specify that it was subject to Article XX of the GATT. Thus although the Protocol of Accession and the rest of the WTO treaty are to be read as a whole in defining China’s rights and obligations, it was successfully argued that this did not amount to permitting later documents (the Protocol) to appeal to earlier ones (Article XX) except where this had been explicitly negotiated. Since the Protocol of Accession negotiated access to Article XX on some issues but not for export restraints, the Appellate Body interpreted its absence in the latter as conscious and binding. There is no evidence that the members of WTO would have resisted such a direct appeal to Article XX, and so it seems to me that the Chinese might reasonably ask the lawyers handling their accession process whether or not they had let their clients down!

Export restraints are just as disruptive to a liberal trading regime as import restraints, and so I would place high priority on disciplining their use. Maybe, as a country that has already largely submitted to such disciplines, China could lead such a negotiation.

A second alleged challenge to Chinese integration into the WTO is the Doha Round, which some, particularly in the United States, held to be stalled because China offered too little. That China should offer a good deal of liberalization was accepted by everyone, including the Chinese, but here I think other countries were making a mountain out of a molehill. China’s accession process was long-lived and entailed a huge amount of reform and liberalization. The Doha Round was initiated as the accession process drew to a close, and was billed both to last only three to four years and to be substantially about continuing the business of the Uruguay Round. In 2001, when it started, no one expected China to play an active role. Over the Doha Round’s extended life, China more than trebled the size of its economy, and it recognized that it had to contribute something. However, the demands made of China for deep cuts in tariffs on manufactured products from the levels agreed at accession seemed quite unreasonable. Certainly China could not stand aside from the general liberalization that a successful conclusion to the Doha Round would have entailed, but to blame China for the demise of the round by not offering more, seems ill-informed.

A further complaint that China might have leveled against the WTO in 2019 is that it offered scant protection against trade barriers that lie at the very edge of or beyond WTO consistency. The United States’ use of the national security argument for restricting imports of steel and aluminum (section 232 of the US code and Article XXI of the GATT) is barely sustainable given many of such imports come from Canada and Mexico with which the USA has virtually impregnable land borders; and the threat of applying similar treatment to imports of motor vehicles is plainly not appropriate. In neither case are China’s exports affected to any great extent, but in terms of undermining the system of which China is a major member (and beneficiary) they are still serious threats.5

Much more directly threatening are the United States’ section 301 actions against imports from China. Justified on grounds of China’s unfair practices in technology transfer, intellectual property, and innovation, the United States imposed tariffs of 25 percent on 818 products worth $34 billion in July 2018, 25 percent on 279 products worth $16 billion in August 2018, and 10 percent on 5,745 products worth $200 billion in September 2018, with the threat to raise them to 25 percent in December unless China desisted. (The latter step is in abeyance in March 2019 while trade talks continue.)

These are unilateral policies that China has little prospect of overturning without signing an asymmetric trade agreement with the United States, and they thus represent the very antithesis of the WTO’s multilateral rules-based system. They are part of a consistent policy of hostility toward China that spreads beyond mere trade—and, indeed, while trade concessions may buy off President Trump, who obsesses about the trade balance, they may well not work on US Trade Representative Robert Lighthizer, who seeks to bring manufacturing back to the United States, or on the US high-tech industry, which wishes to use trade policies to cripple or destroy China’s efforts to achieve technological parity with the United States.6 By mid-2020, after a brief pause, commercial strife had resurfaced at increased levels of intensity with sanctions against a leading Chinese company (Huawei), diplomatic spats, and very hostile rhetoric, especially around human rights. Coupled with the aggressive instincts of the White House, it manifestly threatens the very fabric of the WTO and makes the restoration of the latter’s standing more important than at any time in its short history.

GLOBAL IMBALANCES AND CHINESE GROWTH

The major complaint against China until recently was its huge current account surpluses over the period 2005–2011 and the resulting massive stock of international reserves. The corresponding deficits elsewhere were held to drain demand out of partner countries (exporting deflation from a different perspective), and the imbalances are frequently named as a major cause of the financial crisis of 2007 and onward. There is little truth in either statement, but it is important to keep them in perspective. Moreover, ten-plus years on from the crisis, after the Chinese surplus has substantially eroded, one might even discern a certain (misplaced) nostalgia for the “old” way of running the world economy with booming demand in China.

Macroeconomically the imbalances of the early 2000s reflected, but also permitted, the boom from 2002 to 2007, with the surplus countries able to increase their output and employment strongly and the deficit countries to maintain high levels of consumption and demand. Of course, we can now see that such growth was unsustainable and that adjustment had to occur, but absent the financial crisis (which was not caused by the Chinese, even if it was facilitated by them), it is not clear that overheating per se created particularly large problems. In the event, however, massive adjustment was required of the world economy; both private and government sectors retrenched to try to restore their balance sheets, hence cutting demand on a very broad front; the financial sector nearly collapsed and subsequently cut back lending vigorously, further curtailing demand. The Chinese government played a very constructive role in addressing the immediate crisis, by supporting Chinese and world demand through a huge investment boom funded by extensive borrowing. This helped to support aggregate demand and also substantially reduced the Chinese trade imbalance. As discussed below, however, in the longer run, this response arguably stored up problems for later.

China did not cause the financial crisis, which rather arose from the combination of light regulation and macroeconomic stress in the new millennium. Rajan (2009) argues that, partly because competitive pressures from China and other low-cost producers constrained real wages among less skilled workers, American policymakers looked to private credit markets to boost their spending power; this, in turn, caused the real estate boom and the stock of toxic mortgages that so burdened the financial system and private portfolios. On the supply side of the credit market, the low returns associated with the loose monetary policy behind this distributional policy and the Great Moderation led banks to incur far too many risks in the search for profits. One should not blame any of this on China, but it is the case that the high level of Chinese reserves and the absence of local instruments with which to absorb high savings in China granted these mistakes huge space in which to work their mischief. The fact that China deposited its surplus dollars in New York kept the merry-go-round running far longer than it would have in other circumstances.

An important question is what lay behind the surpluses? Macroeconomics is basically the process of unpicking the relationships between several endogenous variables. While clearly booming exports and stagnating imports were the proximate causes of the Chinese current account surplus, they were not the underlying causes. Export growth accelerated from about 2001 partly because China’s accession to the WTO encouraged foreign direct investment (FDI) from Japan, Taiwan, and Korea. There was also a significant slowdown in import growth after 2004 mainly as net imports of heavy industrial products fell. This partly reflected a buildup of the stock of equipment over the preceding few years, but also the shift in Chinese capabilities so that domestic supplies increased strongly. These changes are partly exogenous and partly symptoms of more fundamental forces.

One frequently proposed causal candidate for the surplus is China’s exchange rate policy, which since around 2004 has been associated with moderate undervaluation. Identifying over- or undervaluation is not straightforward, and while some undervaluation of the renminbi is clear, claims of major undervaluation seem misplaced. For example, between 2005 and 2010, unit labor costs in China increased by about one-third, and the nominal effective exchange rate appreciated by 14 percent; and between 2010 and 2013 the figures were over 50 percent and 11 percent respectively.7 That China chose to keep its real exchange rate relatively low stems from three strong policy imperatives. The first was to sustain employment growth in its export industries with the twin related objectives of maintaining its high rate of export-led growth and of preserving “social harmony.” Chinese policymakers were conscious of a trade-off between political reforms and economic returns: crudely characterized, as long as employment and real wages keep growing rapidly, the population will tolerate the constraints on political freedoms and not seek to disturb the Communist Party’s hold on power. Many commentators spoke of a 7 percent per year threshold below which social unrest will occur, but as far as I am aware, this was based on no formal analysis.

Chinese policymakers, who in my experience are extremely hard-headed and well informed, undoubtedly recognized that a slowdown in growth was inevitable at some stage, but their political masters have found it much more comfortable to postpone the difficult adjustment a bit longer. The period from 2016 to 2019 illustrates this well: each effort to curtail credit expansion is followed by a relaxation as growth begins to falter. And all of this has been accompanied by increasing intolerance of political dissent.

The second imperative was to self-insure against a repeat of the 1997–1998 crisis in which many Asian countries felt abused by the international system and specifically by the International Monetary Fund in return for emergency borrowing. Quite consciously and at times explicitly, they said never again would they risk falling under the influence of the “Washington consensus.” The result was a massive accumulation of reserves throughout most of Asia, and I believe that China was part of that movement based on its observation of its neighbors rather than its own direct experience. In both of these objectives, past exchange rate policy had been extraordinarily successful, and we should appreciate the difficulties that policymakers face in shifting to a different strategy at the behest of other countries.

The third imperative was that a large and rapid exchange rate appreciation would have created large paper losses in renminbi for the holders of dollar assets. To the extent that these were the commercial banks, there could easily have been a messy banking crisis, for received wisdom is that the banks are already burdened by very high levels of nonperforming loans. While the Chinese government has the resources to support and recapitalize the banks if necessary, it is very nervous about processes that it cannot fully control and dislikes acting under duress. Of course, the reserves held by the Bank of China (over $3 trillion at their peak) would also show large paper losses when appreciation occurred, but these would have been easier to gloss over than those in the commercial sector.8

The true cause of China’s large current account surplus was macroeconomic imbalance—high net savings by the household, corporate, and government sectors. Chinese households have high savings relative to those in many developing countries, but, at about 20 percent of GDP, not unprecedentedly so.9 Moreover, given the very rapid rate at which China’s population is aging, the one-child policy, and the relative lack of government-provided services and pensions, high savings seem rational and likely to persist. Much more unusual are enterprise savings, which accounted for about 20 percent of GDP in the mid-2000s. Lane and Schmukler (2007) argue that these reflect the low (zero) dividends paid by private (state) firms coupled with policies that boost enterprise profits strongly—subsidies to inputs such as land and borrowing and low wages supported by rural-urban migration. Until these distortions are addressed and ways found to switch corporate profits into consumption (possibly via the government account with taxes and social expenditure), the imbalances will not be permanently cured.

As noted above, China leaned into the wind as world demand collapsed in 2008–2009 by stimulating official borrowing and investment and was praised for doing so. However, as was argued at the time and has subsequently proved correct, the investment exacerbated Chinese excess capacity in manufacturing and significantly increased the stock of bad debt. Hence this policy made the inevitable cyclical downturn as these positions were unwound deeper and longer, and made the climb toward a long-run sustainable growth path even steeper. As was already clear in 2007, this path requires the Chinese economy to switch from investment and exports as drivers to domestic consumption and innovation. The combination of a steep cyclical retrenchment with a dramatic change in growth strategy and the inevitable slowing as the economy gets closer to the technological frontier and the population ages poses a significant policy challenge for the Chinese government. Growth fell from around 10 percent per year in 2010–2011 to around 7 percent in 2013–2014 to 6 percent in 2018. At least some commentators now fear that it is not a Chinese boom but a Chinese bust that will pose the greatest macroeconomic challenge.

EXCLUDING AND CONSTRAINING CHINA

China’s formidable growth has provided a series of challenges for the current high-income countries and the international institutions that they tend to dominate. These range from the serious competitive threat that China has posed to Western industry (and hence, perhaps, incomes) through the challenge to the Western liberal economic model to the strategic challenge as China starts to seek influence in its region and in the world commensurate with its economic power. Thus the Western attitude toward China evolved from welcoming in the 1980s to a much more defensive posture in the first half of the 2010s, which sought, inter alia, to curb China’s export expansion and oblige it to liberalize its policies, especially toward state-owned enterprises. As already noted, after 2016 the United States became much more overtly hostile toward China, if more random in its policymaking. In this section, I consider two past examples and one current example of such exclusionary behavior. These are the “out” in the chapter’s title.

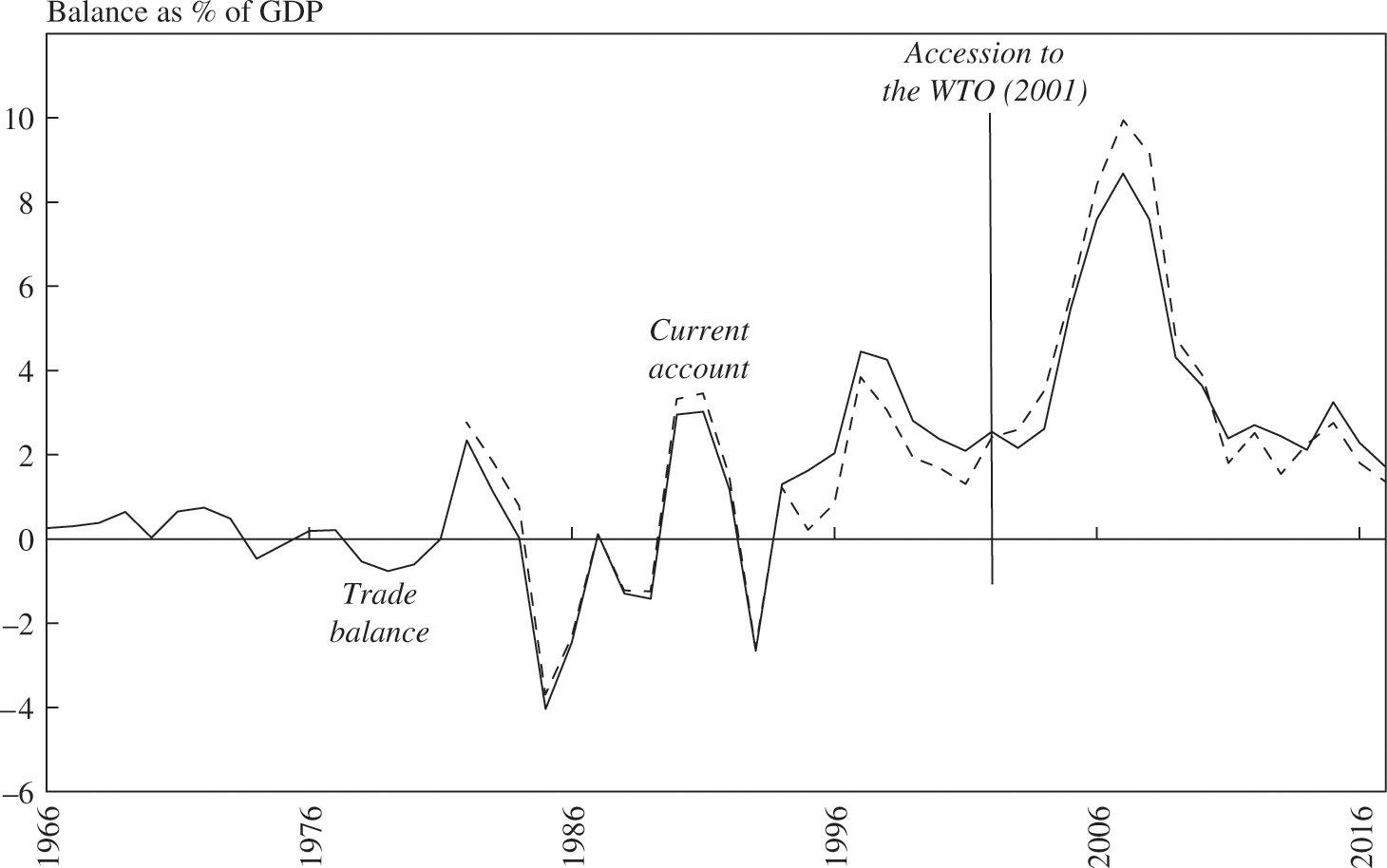

The first example goes back to global imbalances. Some commentators—such as Rodrik (2010)—appealed to something like figure 4-2 to argue that trade and trade policy lay behind China’s massive current account surplus: crudely the argument was that because the surplus boomed as a percentage of GDP shortly after China’s accession to the WTO, the latter must have been responsible for it.10 I deal with this at some length for two reasons: first Patrick Messerlin and I have both argued over the years that the interventionist conclusions derived from this view were wrong; second, the problem has now largely dissipated on its own, which suggests that the rush to change institutions to solve it was as unnecessary as it was dangerous to the world trading system.

Rodrik’s argument starts with the assertion that economic growth (and certainly China’s growth strategy) requires a rapidly growing tradable manufactures sector, because this is typically where the highest productivity activities are found. An intense focus on this sector does not occur with market forces alone because of a variety of market failures—poor property rights protection, unrequited spillovers between firms, coordination failures, and others, which impinge disproportionately on this sector. Hence activist polices are required and have, says Rodrik, been used in virtually every case of successful growth. Countries have variously used polices such as directed credit, production subsidies, export subsidies, and protection to achieve tradables growth. Exchange rate undervaluation can also be used and is historically associated with rapid growth, and its use as a growth policy is attractive because it does not require sector-specific interventions, which are both difficult to design and subject to capture.11

FIGURE 4-2. China’s Trade Balance and Current Account, 1966–2016 (percent of GDP)

Source: World Development Indicators Online, March 7, 2019.

Note: Trade balance is the difference between exports of goods and services and imports of goods and services, both as a percentage of GDP; WDI Online does not report the Chinese current account on a balance of payments basis before 1982.

One of Rodrik’s innovations is to stress that growth is related to the production of tradables, rather than to their export. This means that if a country can simultaneously increase the demand for tradables along with their supply, it can grow rapidly without a large trade surplus. Subsidies, possibly bolstered by protection to prevent demand seeping abroad, are the obvious route to do this, and this is the way in which industrial policy works. Rodrik argues that optimal intervention would see all countries using subsidies to cure their local market failures and that in this case the spillovers between countries would become irrelevant because each country would be at its optimum. According to Rodrik, the problem until 2011 was that WTO membership prevented China (and other countries) from using subsidies, so the government had to turn to exchange rate undervaluation as a second-best tool to boost tradables. But undervaluation must inevitably lead to surpluses, he argues, and that is why the WTO is responsible for the global imbalances. The “obvious” solution to this, about which Rodrik (2011) is explicit, is to restore the legitimacy of unilateral trade and industrial policy, specifically subsidies, and to manage exchange rates multilaterally.

Rodrik’s writing is seductive, but his analysis is wrong in several respects. First, there are many ways to boost tradables output that are WTO-consistent—for example, improving logistics, labor training and education, and consumption subsidies. They are arguably less immediate and direct than straight production subsidies, but they are not ineffective. Second, subsidies and protection are just as dangerous to the world economy as trade surpluses. Consider, for example, the intense reactions of partners’ industries to subsidies elsewhere, which can easily set off subsidy wars of the sort that we saw in the 1930s (which also saw competitive devaluations, by the way). The idea that the optimal intervention offers a stable solution to the global policy game is a chimera—almost certainly this situation is characterized by a prisoner’s dilemma in which country A wants to subsidize and to prevent country B from doing so. There is no guarantee that a subsidy-permissive regime would not degenerate into a subsidy free-for-all with massive intervention. The current clamor against China’s state-owned enterprises is evidence enough of how unpalatable partners find a major player’s subsidies, actual or merely suspected. And we find greater propensity to subsidize industry in nearly every government in the world.

Third, it is also hard to manage exchange rates. The global community has many times called for exchange rates to be managed by the IMF and has always failed; efforts through other groups such as the G-7 have only rarely succeeded. The United States has no intention of surrendering its exchange rate sovereignty to the IMF or an equivalent body, so no WTO-like enforcement mechanism for exchange rates is imminent. There is just no evidence that countries that compete in subsidy space as Rodrik would allow would willingly surrender their policy space in exchange rates. I am not arguing that some coordination over exchange rates is not desirable, just that it is hardly feasible.

If Rodrik’s idea to ditch the subsidies disciplines of the WTO and replace them with an exchange rate code seems dangerous, the pressure from some commentators to take exchange rates into the WTO, and hence to make them subject to the WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism, seems equally so. Mattoo and Subramanian (2009) make the case and it has been taken up by several US representatives and European politicians. Because the complexity of measuring undervaluation is great, the whole basis of a dispute will be contentious, and still more so will be the identification of the government manipulation that is alleged to cause it. Mattoo and Subramanian say these calculations should be done by the IMF and that their doing it on behalf of the WTO will somehow make it politically less contentious than the WTO’s doing it on its own behalf, but I do not see why. One reason WTO’s codification of trade interventions is effective is because it replaces political pressures with technical definitions with a very narrow focus. The process is not perfect, but it tends to draw the political poison. There seems little chance that with something as complicated as macroeconomic management, the same trick will work—see, for example, Staiger and Sykes (2010) on the difficulties of even defining exchange rate undervaluation in WTO terms.

It is difficult to see how trade sanctions will address exchange rate frictions effectively: trade sanctions will not cure macroeconomic distortions, at least not without massive cost. Moreover, because they would be aimed against the whole tradables sector, they would largely lack the ability that “regular” sanctions have to switch the cost of one tradable sector’s protection to another exporting one. But that is not the big worry. The big worry is that trying to use sanctions in this way will inflict major damage on the WTO as an institution, and that by giving it an impossible brief we will destroy the value that we currently reap form the WTO and take for granted. The WTO has neither the structure (all decisions are made by committees of members; none by the secretariat, which might be better able to maintain a technical view) nor the institutional robustness to be able survive the sort of contentious and high-stakes decisions that dispute panels and the Appellate Body would have to take in exchange rate cases. Having failed in such cases, the magic that currently leads to high degrees of compliance with WTO decisions would be destroyed, and we would be left with little leverage against “regular” violations. Once this happened the chances of other cooperation—for example, that in committees on other business—would also disappear. In other words, I fear that hanging the exchange rate millstone round the WTO’s neck would bring it down. Of course, given the United States’ policy of blocking the appointment of Appellate Body members has emasculated half of the dispute settlement process, the WTO as an effective organization might not last long enough for any of this to matter.

The second example of ‘out” was the so-called megaregional trade deals—the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).12 The former was a trade agreement concluded between twelve Pacific countries—Australia, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, the United States, and Vietnam. They had a combined GDP of $27.8 trillion (37 percent of the global total), total trade of $11.6 trillion (26 percent) and a combined population of about 802 million (11 percent).13 There were several possible motives for the US proposal to enlarge the preexisting Pacific-4 Agreement into the TPP in 2008. For example, it may have been an attempt to revive the flagging Doha Round in the WTO; or an attempt to reinterest US business in international trade policy, which was necessary because it had expressed next to no interest in the Doha Round; and to some, it was a way for President George W. Bush to embarrass the Democratic Party because they would have to choose between a probusiness position (supporting TPP) or a prolabor one (opposing it). Virtually all Americans agreed, however, that it was a chance to bind a significant number of partners to the American conception of economic policy, and most believed that in doing so they would counter China’s growing influence on East Asian countries.

Modeled substantially in the US image, the TPP provided for liberalization of agriculture, government procurement and e-commerce, significant labor clauses, significant restraints on state-owned enterprises, and much stronger intellectual property protections. Most of these would involve China in huge reforms that would clearly stretch its political consensus severely, possibly to the breaking point. Moreover, whereas Vietnam was to be permitted long adjustment periods and a degree of latitude in enforcement, any realistic reading of Sino-US relations suggests that China would have received no such concessions.

Once the members of the TPP had accepted these norms, they would naturally press, along with the United States, for other countries to adopt them. Thus there would suddenly have been a coalition accounting for nearly 40 percent of world GDP proposing a specific set of rules within the world trading system, which would have been very hard for other countries to resist. The TPP was essentially an attempt to define trading standards not merely for its members but for the world. I argued this in Winters (2014), and it was made explicit in October 2015 by President Barack Obama in his weekly radio address, stating that “without this agreement, competitors that don’t share our values, like China, will write the rules of the global economy.”14 If China, India, or Brazil felt that these disciplines were too arduous or just did not fit their needs, the world trading system would effectively be sundered. Moreover, given that the TPP would be attractive to smaller economies and that the latter would probably be offered quite accommodating terms, the split would tend to deepen over time rather than the opposite.

The second brick in the wall to exclude China was the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. The TTIP had many parallels with the TPP and sought to go further with deeper agreement on regulatory issues. An avowed aim was to “strengthen the multilateral trading system” and “to enshrine Europe and America’s role as the world’s standard-setters” (European President Van Rompuy).15 This reads very much like an agreement to cooperate to make sure that outcomes in the trading system are as the US and EU wanted them—and with around half of world GDP between them and a further 15 percent in the rest of TPP, the choice facing the others would have been capitulation or exclusion.

In 2014, Patrick Messerlin and Jinghui Wang suggested that the EU and China should reach a trade accord of their own. Although I do not like discriminatory arrangements in principle, it would at least have offered an alternative locus of rule writing to the TPP. But in fact, the Europeans became wholly focused on negotiating the TTIP, which consciously or otherwise provided the United States with the perfect lever to preclude EU-China collaboration. Any such effort that got close to a conclusion could be stopped by a US hint that it might drop out of the TTIP.

Although the United States failed to exclude China from effective membership in the world trading system by introducing exchange rate manipulation as a cause for trade remedies, its indirect approach of building a rule-making coalition that could more or less impose rules on the rest of the world seemed close to fruition. China was, indeed, potentially “out” of the system for a decade, and I, for one, could not rid my mind of Cordell Hull’s strictures about discrimination: “You could not separate the idea of commerce from the idea of war and peace.… Wars were often largely caused by economic rivalry conducted unfairly” (Hull 1948, 84).

But then Donald Trump seemed to ride to the rescue. The TTIP was already making slow progress and received no encouragement from Trump. Immediately on taking office in January 2017, President Trump withdrew the United States from the TTP. The carefully constructed wall crumbled. It is true that, rather surprisingly, the other eleven members transformed the TPP into a new agreement—the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement on Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), maintaining most of the characteristics that the former inherited from its parent, America. But without the world’s largest economy, the CPTPP is unlikely to have a serious impact on world regulatory standards. The TTIP, meanwhile, just faded away.

The demise of the TPP did not, however, presage a period of stability. Soon into his administration, Trump’s mercantilist instincts and his fiercely anti-China trade team combined to renew the effort to exclude China, but this time not through a subtle and sophisticated process of building coalitions, but by brute force. As I briefly described earlier, the United States initiated a hostile trade policy and a rhetorical campaign against China free of any subtlety at all. Eventually China will have to liberalize further if it is to prosper, and it is at present moving in the opposite direction. It is possible that Trump’s overt hostility will have the desired effect, but the descent into bilateralism and power politics means that the cost to the world trading system and all those who rely on it could be very large.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

China’s economic rise has been remarkable—faster and far larger than we have ever seen before or could even have dreamed of four decades ago. The benefits in terms of increased global output and income are large, and, at least to the extent that these are manifest in rising commodity prices, they are shared with some of the poorest countries in the world. Adjustment to such a shock is inevitably painful at times and in places, and I have identified several such instances in this chapter. However, while the first twenty-five years of adjustment to China’s emergence were characterized by strong Chinese growth and mostly accommodating policies among established powers, the period since 2005 has been characterized by increasing angst on the part of other countries. This in turn has led them to move from a position that was generally accepting and welcoming (with some exceptions, of course) to one in which the prevailing sentiment, especially in the United States, appears to be one of fear and exclusion.

The events discussed here certainly do not suggest that the advanced nations face no costs in adjusting to China, or that we do not need to reform the WTO, especially in the area of state-owned enterprises. However, I would argue that other countries have been large beneficiaries of Chinese growth and that some of the issues that have concerned them have cured themselves in the natural course of events. Thus I do not believe that we would be well advised to make fundamental changes to the world trading system rules in order ease the stresses perceived to be emanating from China. Rather we should seek to preserve the multilateral system that is the pinnacle of the postwar settlement and seek to engage China as an equal in a cooperative fashion.

NOTES

1. The differences reflect different ways of aggregating across countries. The smaller estimates weight countries’ endowments together by their shares of world trade, the larger ones by shares of world labor force.

2. In additional tests we show that skill-intensive firms fare better than less skill-intensive ones and that larger firms and products appear to be better placed to take advantage of the improved and cheaper flow of intermediate inputs that Chinese expansion entails.

3. The model is based loosely on a Bertrand model of duopolistic interaction with differentiated products, whereby producers compete via prices, as used, for example, by Chang and Winters (2002).

4. Karapinar (2011) offers a good discussion of the raw materials case. Bond and Trachtman (2016) cover the rare earths one. In the interests of transparency I note that I advised the European Commission in the latter case.

5. The “solution” to these tariffs for several partners has been to agree to voluntary export restraints (gray area measures), which undermines one of the principal achievements of the Uruguay Round.

6. The depth of American angst about China can be gauged by a speech by Vice President Mike Pence at the Hudson Institute on October 4, 2018, which bordered on the hysterical. See “Remarks by Vice President Pence on the Administration’s Policy Toward China,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-vice-president-pence-administrations-policy-toward-china/.

7. Unit labor costs are from US Department of Commerce, “Labor costs” (https://acetool.commerce.gov/cost-risk-topic/labor-costs); exchange rate data are from the IMF’s International Financial Statistics, via the eLibrary (https://data.imf.org/regular.aspx?key=61545850).

8. The losses are just as real, however, and as Larry Summers has observed, China is very far from maximizing its economic returns by building up such reserves of inevitably depreciating assets.

9. See Vincelette and others (2010, fig 2) for the data.

10. Figure 4-2 reports the trade balance over a long period but the current account only since 2005, because these are the only data now in World Development Indicators Online (https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators). In an earlier version of this chapter I used current account data over the period 1980–2011, and they told exactly the same story.

11. Undervaluation’s disadvantage of taxing the consumption of tradables appears to count for rather little with governments focused on growth.

12. More detail on the arguments in the next few paragraphs can be found in Winters (2017).

13. All statistics come from WDI online and refer to 2013.

14. “Obama Jabs at China as He Defends TPP Trade Deal,” October 10, 2015, http://news.yahoo.com/obama-jabs-china-defends-tpp-trade-deal-131620791.html.

15. “Remarks by President Obama, UK Prime Minister Cameron, European Commission President Barroso, and European Council President Van Rompuy on the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership,” June 17, 2013, www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2013/06/17/remarks-president-obama-uk-prime-minister-cameron-european-commission-pr.

REFERENCES

- Autor, D. H., and others. 2014. Trade Adjustment: Worker-Level Evidence. Quarterly Journal of Economics 129 (4): 1799–1860.

- Bond, E., and J. Trachtman. 2016. “China-Rare Earths: Export Restrictions and the Limits of Textual Interpretation.” World Trade Review 15 (2): 189–209.

- Broda, C., and J. Romalis. 2009. “The Welfare Implications of Rising Price Dispersion.” Working Paper. Clemson University. http://economics.clemson.edu/files/priceinequality-july18.pdf.

- Broda, C., and D. Weinstein. 2010. “Exporting Deflation? Chinese Exports and Japanese Prices.” In China’s Growing Role in World Trade, edited by R. Feenstra and S. Wei, 203–27. University of Chicago Press.

- Chang, W., and L. A. Winters. 2002. “How Regional Blocs Affect Excluded Countries: The Price Effects of MERCOSUR.” American Economic Review 92 (4): 889–904.

- Collins-Williams, T., and R. Wolfe. 2010. “Transparency as a Trade Policy Tool: The WTO’s Cloudy Windows.” World Trade Review 9 (4): 551–81.

- Feenstra, R. C., and A. Sasahara. 2018. The “China Shock,” Exports and US Employment: A Global Input–Output Analysis. Review of International Economics 26 (5): 1053–83.

- Hsieh, C., and R. Ossa. 2016. “A Global View of Productivity Growth in China.” Journal of International Economics 102: 209–24.

- Hull, C. 1948. The Memoirs of Cordell Hull. 2 vols. New York: Macmillan.

- Iacovone, L., F. Rauch, and L. A. Winters. 2013. “Trade as an Engine of Creative Destruction: Mexican Experience with Chinese Competition.” Journal of International Economics 89 (2): 379–92.

- Kamin, S., M. Marazzi, and J. Schindler. 2006. “The Impact of Chinese Exports on Global Import Prices.” Review of International Economics 14 (2): 179–201.

- Karapinar, B. 2011. “China’s Export Restriction Policies: Complying with ‘WTO Plus’ or Undermining Multilateralism,” World Trade Review 10 (3): 389–408.

- Kennedy, M. 2012. “China’s Role in WTO Dispute Settlement.” World Trade Review 11 (4): 555–89.

- Lane, P., and J. Schmukler. 2007. “International Financial Integration of China and India.” In Dancing with Giants: China, India, and the Global Economy, edited by L. A. Winters and S. Yusuf, chap. 3. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Maddison, A. 2007. The World Economy. Vol. 2: A Millennial Perspective; Vol. 2: Historical Statistics. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Martin, W. J., and K. Anderson. 2011. “Export Restrictions and Price Insulation during Commodity Price Booms.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 94 (2): 422–27.

- Mattoo, A., and A. Subramanian. 2009. “Currency Undervaluation and Sovereign Wealth Funds: A New Role for the World Trade Organization.” World Economy 32 (8): 1135–64.

- Pang, W. L., and L. A. Winters. 2012. “Exporting Deflation? The Effect of Chinese Competition on Mexican Export Prices. Mimeo, University of Sussex.

- Petri, P., M. Plummer, and F. Zhai. 2011. “The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Asia-Pacific Integration: A Quantitative Assessment.” Working Paper, Economics Series 119. Honolulu: East-West Center. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/22298.

- Rajan, R. 2009. How Hidden Fractures Still Threaten the Global Economy. Princeton University Press.

- Rodrik, D. 2010. “Making Room for China in the World Economy.” American Economic Review 100 (2): 89–93.

- ________. 2011. The Globalization Paradox: Democracy and the Future of the World Economy. New York: W. W. Norton. Sharma, R. 2011. “Food Export Restrictions: Review of the 2007–2010 Experience and Considerations for Disciplining Restrictive Measures.” Commodity and Trade Policy Research Working Paper 32. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization.

- Staiger, R., and A. Sykes. 2010. “Currency Manipulation and World Trade.” World Trade Review 9 (4): 583–627.

- Vincelette, G., and others. 2010. “China Global Crisis Avoided, Robust Economic Growth Sustained.” Policy Research Working Paper 5435. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Winters, L. A. 2014. “The Problem with T-TIP.” VoxEU, May 22, 2014. www.voxeu.org/article/problem-ttip.

- ________. 2017. “The WTO and Regional Trading Agreements: Is It All Over for Multilateralism?” In Assessing the World Trade Organisation: Fit for Purpose, edited by M. Elsig, B. Hoekman, and J. Pauwelyn, 344–75. Cambridge University Press.

- Winters, L. A., and S. Yusuf, eds. 2007. Dancing with Giants: China, India, and the Global Economy. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

- Wood, A., and J. Mayer. 2009. “Has China De-industrialised Other Developing Countries? Review of World Economics 147 (2): 325–50.