The Widow of Hardscrabble

IN MARCH 1925, the supernatural was greatly in vogue among the citizens of Cleveland, Ohio. Harry Houdini had come to town to fight still another battle in his relentless campaign against fraudulent spiritualists. At noon on Friday the 13th, he staged an imitation of a seance at the Palace Theatre in Playhouse Square for a spellbound audience of 1500, including ministers of many of the city’s churches. In the course of his impersonation of a fake medium, Houdini exposed a number of that shameless profession’s most dazzling effects, including floating trumpets, strange voices, and baby hands that touched clergymen who volunteered to be tricked. Departing from the usual reticence of the prestidigitator, Houdini explained how he achieved an apparently magical phenomenon of spirit-writing by the simple device of having an accomplice substitute a slate with a chalked message.

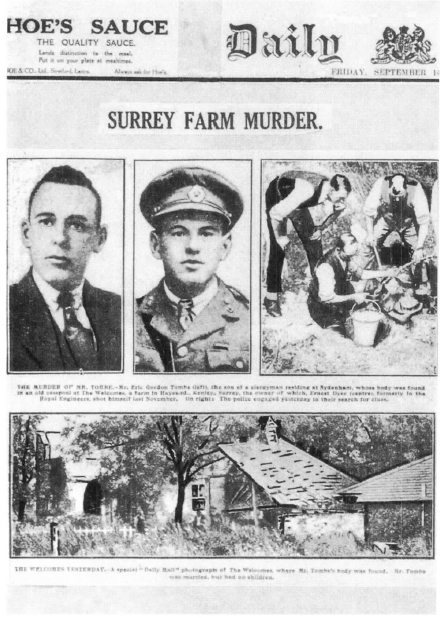

To the right of its double-column-on-front-page account of the theatrical triumph of the ‘world’s greatest mystifier’, the Cleveland Press published its first report of the hunt for a ‘super-killer’ in neighbouring Medina County. As news developments in the case broke at a dizzying pace in the succeeding weeks, the facts of the bizarre crime were to become shrouded in claims of diabolic influence that were ultimately tested, not by a Houdini, but by the common sense of an Ohio jury.

The first sign of trouble was a series of unexplained barn-burnings. The little rural Medina County community of Hardscrabble, located near Valley City in Liverpool Township, about thirty miles southwest of Cleveland, was beset by trivial mysteries as well: disappearing jewellry and thefts of wheat and farm implements. It was the fires, though, that most severely disrupted the efforts of the predominantly German Lutheran farmers to wrest a living from the soil of their fields. The first blaze consumed the barn of Mother Gayer, and similar calamities befell Howard Grabbenstetter and Edward Bauer. Villagers whispered about the possibility of an arsonist in their midst; but when two years passed without any more emergencies for the local fire brigade, it seemed that peace had been restored to Hardscrabble.

In 1924 Medina County seemed to be caught up in the unremarkable rhythm of birth, marriage and death celebrated in Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. On 16 December, in its regular column headed ‘The Way of Life’, the Medina County Gazette reported the passing of a woman who had attained the biblical age of three score and ten:

HASEL. At Liverpool, on December 13, Mrs Sophie Hasel, aged 72 years, 13 months and 16 days. Funeral at Zion Lutheran Church, Dec 14, at 10 am. Burial at Hardscrabble Cemetery.

If Sophie Hasel’s death appeared commonplace, her funeral proved to be unpleasantly out of the ordinary. After a reception at the Hasel home, five relatives took ill: Sophie’s son Fred, his wife and their fourteen-year-old son Edwin, as well as Fred’s brothers, Henry and Paul.

On New Year’s Day, 1925, it was the turn of Sophie Hasel’s brother, fifty-nine-year-old Fred Gienke, Sr, and his family to be stricken by a sudden malady. After eating a dinner of warmed-over pork, Fred, his fifty-two-year-old wife Lillie, and four of their six children, Marie (twenty-five), Fred, Jr (twenty-four), Rudolph (seventeen) and Walter (nine), became seriously ill. Lillie Gienke died on the morning of Sunday, 24 January; the hospital doctors speculated about the possibility of a botulism, but the Medina County Gazette death-notice settled generically on ‘ptomaine’. Lillie’s body was laid to rest in Hardscrabble Cemetery, a few steps away from Sophie Hasel’s fresh grave.

The strange illness attacked the entire surviving Gienke household again on 16 January. This time the two other children, Herman, who was twenty-one, and Richard, a year younger, were also afflicted, as well as Mrs Rose Adams, Lillie Gienke’s sister, who was paying a condolence visit. The family physician, A.G. Appleby, of Valley City, two miles to the south, summoned the Medina County Health Commissioner, H.H. Biggs, who took blood specimens from each member of the family. Dr Biggs also dispatched to the Ohio state health department in Columbus samples of the well-water that the Gienkes used for drinking and cooking, and of the lard which had been used in the two meals that had sickened them. Provisionally, Dr Biggs ruled out the recurrence of a botulism, on the ground that the second illness of the Gienkes had come on too quickly after eating; an alternative theory of typhoid was excluded by the results of the blood-tests.

By 3 February Biggs was ready to calm the fears of the residents of Medina County that a dangerous epidemic was at work. He told the Medina County Gazette that another report from the state health authorities, focusing on the Gienkes’ food, showed no evidence of toxic poisoning; the analysis of the household water was still awaited. Unfortunately, the comfort offered by Biggs was premature. On 6 February, a powerful third wave of illness swept the Gienke home: Fred Gienke, Sr, and his children Rudolph and Marie were taken to the hospital; a Cleveland nurse, Mrs Rose Kohli, who had been attending the Gienke family, was also stricken. Two days later, Fred Gienke died in the Elyria hospital, and a few days afterwards was buried beside his wife in the little cemetery on Myrtle Hill in Hardscrabble. According to the Gazette death-notice, the post-mortem examination of Mr Gienke’s body had revealed ‘nothing extraordinary’.

It was only on 13 March that Gazette readers learned that the facts of the investigation had been largely withheld from them. Under a screaming headline, GIENKE FAMILY WERE POISONED, the paper revealed that arsenic had been established as the cause of the deaths of Lillie and Fred Gienke and of the serious conditions of Rudolph, Marie and young Fred. Final confirmation of arsenical poisoning had been provided by analysis of blood and feces obtained from Marie and Rudolph; the Medina authorities now admitted that a post-mortem examination of the contents of Fred Gienke’s inflamed stomach, previously reported to have been ‘uneventful’, had not yet been undertaken. According to county prosecuting attorney Joseph A. Seymour, the authorities had known for some time that the Gienkes had succumbed to arsenic but had kept that fact from the public ‘in the hope that some clue could be discovered that would lead to information as to how the poison was administered’. Insisting that he had not yet targeted a suspect, Seymour would not even say whether the arsenic had been intentionally added to the Gienkes’ food or drink. However, he ventured the opinion that the poison had been ingested in coffee, and revealed that he was holding part of the contents of a package of unbrewed coffee for analysis. While Seymour performed his demure fan-dance with the truth, the Cleveland Press was more outspoken, declaring that the medical findings had stimulated a ‘hunt for a super-murderer who kills for the mere joy of killing’.

Significant progress in clearing up the mystery was reported in the Gazette of 17 March, although it remained obvious that full disclosure was hampered by the reticence of Medina officials. The coffee trail was still a major clue. Although the tests of the unused coffee had been negative, Fred Gienke, Jr, had observed that many relatives had become ill with abdominal pains and muscle-stiffening after drinking the beverage in his home and in the house of his grandmother Sophie Hasel – who was now for the first time identified as another murder-victim. Fred Jr had tried unsuccessfully to persuade the Medina officials and Cleveland chemists to analyse the Gienkes’ blue-and-white coffee-pot, containing literal grounds that he had taken care to preserve. Despairing of the chances of interesting the investigators in his theory, he repossessed the pot and entrusted it to the city chemist of Elyria. ‘I’m certain it was the coffee,’ the young man maintained. ‘I’ll pay for the examination of this coffee and satisfy myself, at least, that the trouble was there.’

As Fred pressed his own inquiry, there was a report that the Medina police had uncovered the possible source of the arsenic. According to the Gazette, the scribbled name of a woman who knew the Gienke and Hasel families had been discovered in a druggist’s registry; the name appeared again in the registry a week later, but then looked like ‘the work of a person attempting to disguise his or her handwriting to conform to that of the person who first signed’. About two grains of arsenic were obtained through the first purchase, and one grain through the second. Prosecutor Joe Seymour commented cryptically that the ‘finding of the registry had not been strengthened by his later investigations’, and did not regard it as definitely established that the purchaser had acquired the poison for murderous purposes, especially since there was no apparent motive for poisoning the Gienke family: ‘Administering of the poison appears at this time to have been accidental or the work of a moron. I have kept knowledge of the poisoning from the public in the hope of a tangible clue to run down, but those who have been investigating with me have found nothing to act upon.’

The prosecutor informed the Gazette that the only poison discovered in the Gienke house was a small amount of insecticide containing a toxic ingredient different from that detected in the blood-samples of Marie and Rudolph, who remained hospitalised in Elyria. Marie was unable to talk or turn her head; Fred Jr, despite the energy he displayed in his coffee-pot crusade, was still having difficulty moving about.

A Slaying on

Saint Valentine’s Day

Part of Lower Quinton, from the tower of the church

Charles Walton

Albert Potter

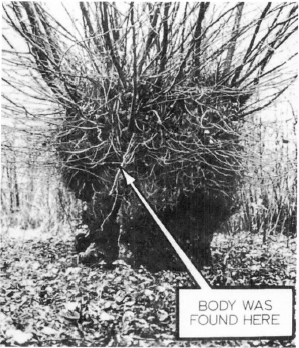

The wych-elm in Hagley Wood

The Widow of Hardscrabble

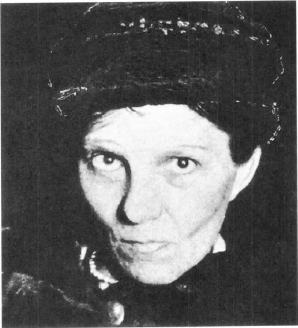

Martha Wise

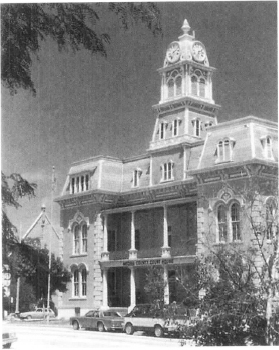

The Medina County Court-House

The Well and the Dream

The Cleveland Press was less willing than the Gazette to accept Seymour’s guarded account of the progress of the investigation. As early as 14 March, the Press headlined that a woman was sought as a poisoner of the Medina family; the slayer was ‘a modern Borgia, who has so cunningly concealed her moves as to leave no single trace of her path of torture and death’. To the Cleveland journalists it was certain that the poison was administered ‘at the instance of someone without the immediate family circle’, and that for prosecutor Seymour it remained only to establish motive, means of administration, and ‘a definite identification of the signatures in the poison book’. Two days later the Press had more to say about the mysterious murderer whose image it had begun to sketch for its readers: she was ‘crazed by hallucinations growing out of certain deals in which the family of Fred Gienke figured’.

On 19 March, all the hints and guesses about a solution of the Hardscrabble poisonings ended with the stunning announcement that the murderess had confessed. She was Martha Wise, a forty-three-year-old widow of Hardscrabble, daughter of her first victim, Sophie Hasel, and niece of Lillie and Fred Gienke, the next to die of her poison. Allene Sumner, a reporter who was permitted to interview the gaunt widow in the Medina jail, wrote that the cold, bare cell was filled by ‘the black breath of the dark ages when a horned personal devil roamed the world, urging men and women on to horrible crimes’. Crouched under her bedclothes, moaning and wailing, the widow ‘pointed a bony finger at the vision of the devil whom she seemed to see standing in a corner of her cell’, and held the Evil Spirit responsible for her actions:

‘Why did he come to me? Me who always lived right and did my best, being weak-minded as I am.

‘He came to me in my kitchen when I baked bread, and he said, “Do it.”

‘He came to me when I walked the fields in the cold damp night, trying to fight him off. He said, “Do it, nobody will know.”

‘He came to me when my children were around me. Everywhere I turned, I saw him, grinning and pointing and talking at me.

‘I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t sleep. I only talked and listened to the devil as he walked through the fields of Hardscrabble.

‘Then I did it.’

The Cleveland Press photographs of Martha Wise show a plain, long-faced woman with thick, dark hair pulled upwards from a square forehead, heavy brows above pouched, staring eyes, and a puffy, almost swollen, mouth. The prisoner told reporter Sumner that the devil had begun to pester her three years before, when her husband Albert, a farmer, died, leaving her ‘alone in the house all day, with nothing around [her] but the wind and the rain and the awful stillness’. Repeatedly the widow asked Sumner to explain the infernal visitations, but the reporter, having no answer, left Mrs Wise ‘shrieking at her devil in the corner’.

The poisoner’s signed confession, published on the following day in the Gazette, was skimpier in its assertion of supernatural pressures, stating merely that the devil was in her. On the other hand, the factual circumstances of the Gienke poisonings were elaborated convincingly: on New Year’s Eve, when Martha (whose cow had gone dry) had walked downhill to the Gienkes’ to fill her bucket with milk, she had put some arsenic in the water-pail that the Gienkes kept in their kitchen for cooking and coffee-making; she had previously poisoned her mother’s water-bucket on the day before the old lady (who had separate quarters in the house where Martha’s brother Fred Hasel lived) took ill.

Martha had pinched more arsenic into the Gienkes’ bucket either in late January or on the first of February. But it was not true, as had been suggested, that she had administered more poison to Marie Gienke during a visit to her hospital-room; instead, she had comforted her paralysed niece with a gift of oranges.

Mrs Wise had bought about two ounces of arsenic at a corner-drugstore in Medina, telling the ‘short, heavy-set man at the counter’ that she wanted the poison to kill rats. Whenever she had set off to put the arsenic in her victims’ buckets, she had carried the dose wrapped in a little piece of paper. Martha separately confessed to the mysterious fires and thefts that had plagued the Hardscrabble district. At first, she hadn’t thought about the risk that the fires would kill anyone, but later she had started setting them at night so that she could ‘surprise people’. She had never stayed at the scene of a fire, preferring to slip away to watch the farm buildings blaze, crackle and burn. She had set the first fire – to the Gayers’ barn – after a son of Mother Gayer had shot one of her husband’s pigs that had invaded the Gayers’ garden.

Prosecutor Seymour opined that the arson confession ‘virtually clinches the insanity case. The possibility of arraigning her on a murder charge is now so remote as to be almost wholly out of the question.’ In view of the real danger that an insanity finding would diminish the exploitation value of the case, the Cleveland Press speedily staged a touching scene beneath the widow’s jail-window: the four Wise children, Lester, Everett, Gertrude and Kenneth, whose ages ranged from fourteen to six, were shown waiting for a glimpse of their mother. ‘She was the best ma any fellow ever had,’ Lester was quoted as saying. ‘The trouble with Ma is that she never did nothing but work with her young ‘uns.’ In a companion-article, however, the Press portrayed Mrs Wise as a woman morbidly attracted to death; she had loved funerals (especially those of her three victims) and on a recent occasion had travelled to Cleveland – on roads rendered almost impassable by soaking rains – to attend the burial of a distant relative; in addition, she had nursed her mother attentively after poisoning her. The Press had learned that the widow’s attraction to death went hand-in-hand with disappointment in love. Her married life had not been happy, since her husband, ‘pressed by his heavy duties in the care of the farm,’ made her ‘a slave to her chores and housework and children’. After Albert Wise’s death, the family farm was sold under a court order to pay debts, and his widow had eked out the purchase of a small house only a quarter of a mile from the Gienkes. Soon Martha had scandalised Hardscrabble’s proprieties by gathering men-friends. The Ladies’ Aid of Zion Lutheran Church of Valley City, which had sent her compassionate gifts of flour, vegetables and clothing, had complained that she was redistributing the food among her male admirers. Local tongues had increased their velocity when the widow circulated rumours that she was going to marry Walter Johns, a Cleveland machinists’ foreman in his fifties. When that project sputtered, Martha had proposed wedlock to another man, but ‘was emphatically refused’. After those two instances of unrequited love, following years of her husband’s coldness, the frustrated widow had turned to arsenic. So said the early reports – but subsequent versions added related grievances. According to the later embellishments, Sophie Hasel, and Fred and Lillie Gienke, Martha’s uncle and aunt, had opposed her marriage to Johns, not so much because he was a decade older but because he was, of all things, a Roman Catholic.

The autopsy performed on the exhumed body of Lillie Gienke revealed a quantity of arsenic sufficient to kill three people; and, as Fred Gienke, Jr had suspected, the belated inspection of the coffee-pot disclosed the presence of the poison in scrapings of the outside metal surface, though the grounds appeared to be harmless.

The prosecution therefore decided to proceed against Mrs Wise for the murder of Lillie Gienke, leaving the prisoner’s sanity as the sole issue.

Mrs Wise showed little interest in the legal proceedings that bound her over to the grand jury, and only twenty or so spectators turned out for the hearing in the extravagantly mansarded courthouse that dominates Medina’s main square. Since no new sensations were produced in the courtroom, the Gazette interviewed Coroner E.L. Crum, who had helped secure the confession. Crum got dangerously close to prejudicing the pending determination of Mrs Wise’s legal responsibility by classifying her as a ‘mental and moral imbecile whose normal side knew little of her subconscious acts,’ and then explaining:

This type usually displays a genius for evil. It is not surprising that she picked holidays – Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day – to administer the poison. A flair for the dramatic would dictate that.

The coroner’s observation that Mrs Wise favoured ‘holiday killing’ was acute, but he failed to notice the special opportunity that family reunions marking festive occasions provided to a woman bent on mass-murder.

In early April, the grand jury, as expected, indicted Mrs Wise for the murder of Lillie Gienke. The prisoner, who until recently had behaved calmly, now began to indulge in little ‘tantrums’, suspiciously as if she were laying the foundation for her insanity defence. Twice she had summoned Mrs Ethel Roshon, the jail matron and wife of the county sheriff, with a false alarm that she had swallowed a safety-pin.

In advance of the trial, set for 4 May, Martha Wise’s relatives made the first effort to demonstrate the widow’s mental incompetency by applying to the Medina probate court for the appointment of a guardian. The petition, signed by Merton G. Adams of Liverpool Township (husband of a sister of Albert Wise), stated that Martha had $1800 deposited in a Valley City bank, and 18 acres of land worth $1500. In the hearing, Mrs Wise stated that she ‘did not know what she was doing’; and Joseph Pritchard, Mrs Wise’s criminal defence lawyer from Cleveland, cited as evidence of the need for guardianship the conflicting instructions his client had given regarding use of her funds for the defence. Although the petition was not seriously opposed, premonitions of the coming battle over the prisoner’s criminal responsibility could be heard. Dr Wood of Brunswick, the Wise family’s physician, testified emphatically that Martha was not insane, while her attorney Pritchard still more emphatically rejoined that ‘she is one of the craziest persons on the American continent’. Arthur D. Aylard, the president of the Medina Telephone Company, was appointed as the widow’s guardian.

The murder trial began with arduous efforts to select open-minded jurors. Since many local residents had fixed views about the defendant’s guilt, the court adjourned on Monday afternoon, 4 May, with two panels of prospective jurors (totalling seventy-four) exhausted, and only eleven tentatively seated. Mrs Wise, who attended in the company of the jail matron, Ethel Roshon, ‘was dressed in a simple blue gingham gown, over it a heavy brown coat and with a simple, old-fashioned black hat. She appeared much pressed, but no different than on her former public appearances.’

On Wednesday, 6 May, when the jury selection was at last complete, the prosecution began to put on its case. By the afternoon, however, the courtroom proceedings were overshadowed by the tragic news that the Medina murders had indirectly claimed a fourth victim. Edith Hasel, the wife of Martha’s brother Fred, had slashed her throat that morning in an outhouse near her Hardscrabble home. Ethel, who reportedly ‘was never strong mentally’, had brooded over the family deaths and ‘imagined that people were pointing to her as the guilty person’. Apparently defence attorney Pritchard had intended to call Ethel Hasel as a witness, for evidentiary purposes that he never revealed, but quite possibly with a view to implanting a seed of doubt in the jury’s mind as to whether the right family member was on trial. With the news of the suicide scurrying around the courthouse, the evidence offered by the state could not fail to be anticlimactic, particularly when the prosecution surprisingly declined to introduce Martha Wise’s signed confession. Instead, Joe Seymour relied on the live testimony of Mrs Roshon, the sheriff’s wife – to whom Martha had first admitted her guilt after her arrest at Fairview Hospital, where she was awaiting a minor operation on her arm.

The highlight of the state’s brief presentation was the testimony of Marie and Rudolph Gienke concerning the effects of the poison they had taken and other incidents regarding their illness. Marie, recently released from the hospital, was brought into the packed courtroom on a cot, and prosecution counsel Arthur Van Epp (who was assisting Joe Seymour, his successor as Medina County prosecutor) had to hold up her hand so that she could take the oath; Rudolph needed to be supported by Sheriff Roshon as he entered. It was on the appearance of her two young victims that Martha Wise gave her first sign of emotion during the trial.

As the defence case opened, the spectators braced themselves for the parade of 139 witnesses whom Pritchard had subpoenaed to support the insanity plea. Martha’s close relatives and neighbours portrayed her as a woman who could well have believed that the Devil had chosen her as his instrument. Emma Kleinknecht of Valley City, a sister, blamed Martha’s disorder on a dog-bite she had suffered when she was fifteen: after this mishap, she had frothed at the mouth and her body was curved tautly backwards in the shape of a rainbow; she had believed that ‘the gates of Heaven flew open to her’ and that she conversed with angels while a cloud of white doves enveloped her. One day during the previous summer, a gentleman caller, encountering Martha lying on the floor of her house, with foaming mouth and glassy eyes, had deduced that her disability had not passed. Another witness swore that he had once heard her bark like a dog, and Emma Kleinknecht said that the widow used to roam the countryside at night.

At the beginning of Friday’s session, Pritchard recalled Ethel Roshon in an attempt to emphasise irrational elements in the misdeeds confessed by the defendant. Mrs Roshon confirmed that Martha had admitted burning several barns and stealing a purse. The defence lawyer, however, lost more ground than he gained in focusing the jury’s attention on the defendant’s quarrel with Sophie Hasel: Mrs Roshon recalled Martha’s having told her, in the intelligent manner she displayed in the entire course of her confession, that the dispute with her mother concerned the prospect of Martha’s marrying a man of a different religious belief.

Martha’s brother, Paul, remembered that as a child she was ‘awful wild and had a temper’. To defend Paul against Emma, who had begun to beat him for some boyish misbehaviour, ‘Martha flew at her and cleaned up on her. Emma had scars for a long time from where Martha scratched her face.’ Many childhood friends remembered Martha as a slow learner who cried easily in school. Two of her arson victims testified charitably that Martha’s husband had not been affectionate and had spoken abusively to her.

On Monday afternoon, 11 May, Pritchard called Martha’s suitor, Walter Johns, to the stand. Although the prosecution speculated that Johns would deliver surprise testimony, Pritchard did not ask the Clevelander a single question. When Judge McClure rejected Pritchard’s request to cross-examine Johns on the basis of his alleged hostility to Mrs Wise, the lawyer abruptly dismissed the witness and closed his case, although only about a third of the persons summoned by the defence had been heard.

In rebuttal of the insanity claim, the prosecution presented expert testimony on Tuesday morning. Dr H.H. Drysdale, a Cleveland psychiatrist, had a very straight-forward explanation for the poisonings: ‘She wanted to marry this man – whoever he is – and she took the poison-method to gain her end, which was to remove the obstacles that stood in front of her desires.’ Dr Drysdale seemed to be speaking less as a man of science than as a spokesman for the Hardscrabble back-fence community – which gossiped, according to the Gazette, that ‘Mrs Wise, rebuked by her mother for having men visitors, poisoned her, then set out to destroy Fred Gienke, Sr, because he admonished her after her mother’s death’. Agreeing with Drysdale that the defendant was responsible for her actions, Dr Tierney, another Cleveland alienist, assured the jury that neither pyromania nor kleptomania was a form of insanity.

Dr Wood, the Wises’ family-physician, rejected the defence hypothesis that Martha Wise was epileptic; he stressed her cunning, evidenced by her suggestion to him that Lillian Gienke had died of influenza. In his closing argument for the prosecution, Joe Seymour laid similar emphasis on the premeditation that was attached to the murder of three persons and the non-mortal poisoning of a baker’s dozen:

Slipping into the Gienke home when no one was watching, pinching arsenic into their water pail, returning twice to add further poison – that’s not the manner in which insane people murder.

Still, the state asked that a verdict of Guilty be coupled with a recommendation of clemency.

Defence attorney Pritchard, in response, regretted that the jury had not been permitted to view the ‘worn path’ connecting the home of Mrs Wise with that of the Gienkes, a sight that would have dramatised the kindly feelings between the two families. He also condemned the authorities’ use of a ‘candy pail’ to convey Lillian Gienke’s stomach from Medina to the Elyria hospital for examination, without indicating that the sugary receptacle might have influenced the autopsy results. After expressing these introductory grievances, Pritchard evoked the forgiveness that Martha Wise’s surviving victims showed for a relative who had lost the power to distinguish between right and wrong. Tearfully, he compared ‘the condition of the ill-fated and physically-crippled Marie Gienke with the queer, mentally-unbalanced Martha Wise, broken in body and broken in mind’.

The jury of seven women and five men found Martha Wise guilty of murder in the first degree, with a recommendation of clemency, returning its verdict only one hour and ten minutes after retiring. The verdict automatically required the imposition of a sentence of life-imprisonment in the state reformatory for women, without possibility of parole.

Immediately after the conviction of Mrs Wise, Medina County authorities turned their attention to one of the men in her life, Walter Johns. On Sunday, 10 May, when the trial was in weekend recess, Lester Wise, Martha’s fourteen-year-old son, had told Prosecutor Seymour that one day last November he had heard his mother discussing poison with a male visitor; when Mrs Wise observed that the boy was listening intently, she ordered him to leave the house. His mother’s trial had already begun when Lester first reported the incident to his aunt, Mrs Merton Adams, who brought the boy to Seymour. ‘I got out my old Bible,’ she told the prosecutor, ‘and Lester swore to me that he was telling the truth.’

On Friday evening, 15 May, Walter Johns was arrested in Cleveland on a warrant charging him with the murder of Mrs Sophie Hasel, and lodged in Medina County Jail. On the following Monday evening, he was confronted with Martha Wise, who now seemed anxious to shift the blame from Satan to her former admirer. ‘He made me do it!’ she shrieked when she first caught sight of Johns. ‘He kept at me to do it! He told me I should get the arsenic and get rid of my mother and then I’d be free and happy.’ When Johns protested that she was lying, she lifted her left hand – but then corrected the gesture, raising her right hand high. ‘I swear it’s true,’ she asserted. ‘He told me that with Mamma gone, I’d be more free.’

The widow backed her charges by claiming that Johns had asked her about a will Mrs Hasel had made before she was poisoned. Prodded by Seymour, she claimed that, without the influence of Johns, she would never have thought of killing her mother. Her lover instructed her ‘how much arsenic to buy and how much to put in mother’s water-pail – half a teaspoon’. Though she did not hate him, forgiveness was out of the question. She would have carried their secret to the grave, but ‘it had to come out’; she was to be punished and wanted to be, but Johns was just as guilty.

While Martha Wise made her accusations about the poisonings, Johns denied everything she said, and so she changed her tactics, seeking his confirmation of the details of their romance. Johns, however, was almost as reluctant to concede their intimacy as to acknowledge a partnership in crime, and after he remained unresponsive to her description of the Gienkes’ sufferings, her exasperation with her lover led to a new outburst: ‘You couldn’t shed a tear to save your soul from Hell!’

John F. Curry, a former Cleveland councilman, who was Walter Johns’s attorney, complained that the widow’s rancour was ‘just a case of a woman scorned’. His client hadn’t gone to see her after she was arrested for the simple reason that he thought a visit might make her feel worse; her false accusations were the result of his considerate restraint.

At length Prosecutor Seymour saw that Martha’s ravings would not breach her lover’s defences, and was constrained to play his final card, which was to demand Johns’s explanation of a letter he had written to the widow when they were on better terms:

Dear Martha,

… Well, now, I suppose you are saying to yourself I guess I won’t hear from that guy any more, but as usual, I have been very busy; it is a poor excuse I understand in this case, but you will excuse me once more, won’t you, Martha; say yes….

I want to say to you that we have a very nice place to live in now, everything our own way and we realise how to take that comfort and enjoy it very much; I wish you could share with our comforts….

Seymour came down hard on the phrase ‘everything our own way’. Didn’t the words suggest that Johns and Mrs Wise had taken steps to clear away the obstacles to their marriage? In fact, the context of the letter plainly suggested a more innocent reading: the writer seemed to be referring to the increased amenities that he and his children found in their new residence which they hoped the widow would share with them. Nevertheless, faced with Seymour’s damning alternative interpretation, Johns appeared to panic. ‘I never wrote anything about “now we have everything our own way,” he insisted; the rest of the letter was in his handwriting, but someone must have inserted the disputed words.

Despite Johns’s equivocal position regarding his letter, Seymour reluctantly concluded that there were insufficient grounds for prosecution and released the nervous machinist on Wednesday, 20 May. On the following Saturday, the convicted widow was taken to the Ohio State Reformatory for Women, in Marysville, to begin her sentence. During her journey – the first long automobile ride she had ever taken – she was accompanied by Sheriff Fred Roshon and his wife Ethel. During her two months of confinement in the Medina jail, Martha had made Mrs Roshon a confidante, speaking freely to her of the crimes – and remarking ominously on one occasion: ‘It’s a good thing you caught me when you did…. ’

Thirty-seven years later, in 1962, the ‘Poison Widow of Hardscrabble’ was paroled after her first-degree murder sentence was commuted to second-degree by Governor DiSalle, and the head of the state’s division of corrections announced that she would be moved to ‘a home for the aged in southern Ohio’. Mrs Wise’s freedom, however, was to be tantalisingly brief. Upon her release, Helen Nicholson, a parole officer, took her to board with Mrs Muriel Worthing in Blanchester, Clinton County. When they arrived, though, Mrs Worthing had changed her mind – ‘fearful of a small town’s reaction’. After this unexpected rebuff, Mrs Nicholson boarded Martha Wise for the night at her own home in Cincinnati. Next day, she returned her charge to prison after learning that the parole had been rescinded pending further study of its practicability.

Six years later, Martha Wise made her last appearance in public print. The Cleveland Plain Dealer described the famous prisoner’s regime at Marysville. Because of her age (eighty-six), she was one of seven permanent patients in the reformatory hospital. For years she had worked in the poultry house, caring for chickens. Superintendent Martha Wheeler referred to her forename-sake as a ‘sweet old lady’, one of the best-liked inmates at Marysville.

Not all readers would have shed tears over the article: certainly not Rudolph Gienke, who throughout his life remained greatly disabled as the result of the paralysis caused by the arsenic poisoning. His sister Marie, also permanently handicapped, recovered sufficiently to marry and live to the age of eighty-one. She now lies at rest in Hardscrabble cemetery, where the Poison Widow dispatched many of her relatives before their time.

Afterword: Spring 1991

Martha Wise died in Marysville Reformatory exactly twenty years ago and was buried there. The details of her crimes are sharply etched in the memory of Walter Wolfe, an eighty-year-old township trustee and respected patriarch of Valley City, who recently escorted the author and his wife on a tour of the sites associated with the Hardscrabble murders. Walter is a descendant of the Gienkes – which is not surprising, he explained when he unlocked the gate of little Myrtle Hill Cemetery and showed us the victims’ graves: ‘In the 1920s, all the local farmers were “shirt-tail” relatives.’ A schoolmate of Martha Wise’s son Lester, Walter recalls his community’s famed poisoner as a tall woman who used to walk ‘cross-lots’ from her hilltop residence to the Gienkes’ place in the valley below. Both of those modest frame-houses still stand. Walter cannot account for the origin of the name ‘Hardscrabble’, because the land in northern Medina County, far from being hard to cultivate, let alone scrabbly, is rich; but the fair-haired wheat that was raised in Martha’s time has now been replaced with less delectable crops such as soybeans and hay.