The Well and the Dream

Between the acting of a dreadful thing

And the first motion, all the interim is

Like a phantasma, or a hideous dream.

HURRICANE-LAMPS FLICKERED like Will-o’-the-wisps among the tall, rank grasses and clutching tangles of weeds on the deserted farm. Their thin yellow beams chased shadows through the overhanging branches, and shone on the bared arms of the searchers, that September midnight.

Shortly before sundown, they had slipped like a marauding band of body-snatchers through the five-barred gate in Hayes Lane, at Kenley, near Croydon, on the south-eastern outskirts of London, to begin their grim and secret hunt at The Welcomes Farm.

For nearly six hours they had been picking and shovelling the rubble of tight-packed earth, crumbling bricks and concrete from two of the farm’s five wells.

Now they were working on the third….

It was a strange story which had brought Superintendent Francis Carlin, one of the ‘Big Four’ of Scotland Yard, and his men to the lonely farm that night. A story which Carlin was afterwards to describe as the most extraordinary in all his thirty-five years’ experience.

It had really begun years before – in 1919. The Great War, which had scythed through ‘the flower of England’s youth’, had ended. The survivors were taking up – or trying to – the threads of peacetime life. Among them were two demobilised Army officers, twenty-five-year-old Eric Gordon-Tombe and twenty-seven-year-old Ernest Dyer.

They had been lucky. In the ‘land fit for heroes to live in’ other young ex-officers were selling boot-laces, but these two had landed respectable jobs at the Air Ministry in London.

Lucky? Their chance-ordained meeting was to spell disaster for both of them.

Someone who knew them at this time was a young ex-gunner officer now helping in his father’s wine business in the Haymarket. His name was Dennis Wheatley. Still fourteen years away from publishing the first of the novels that were to make him the widely acknowledged ‘Prince of Storytellers’, he could not have guessed that these two young men were to act out a real-life mystery as bizarre as any tale ever to come from his imaginative pen.

He told me: ‘I met young Tombe in a camp for convalescent officers in the spring of 1917. We shared a hut together for several months. I resumed my friendship with him after I was invalided back from France. Dyer I met only a few times, but there was something about him I didn’t like.’

Dyer had big schemes. Motoring and horse-racing, he said, signposted the road to great fortunes. Tombe had £3000 in the bank. They decided to go into partnership.

Two motor businesses were started – at Harlesden, north London, and in Westminster Bridge Road. Both failed. The partners then purchased a race-horse training stable and stud farm – The Welcomes – Tombe putting up the greater part of the money. That was in 1920.

Dyer, his wife Annie, and their three children lived in the farmhouse. Tombe stayed either at his flat in the Haymarket or, less often, at a hotel in Dorking, ten miles or so south-west of Kenley.

Shortly before nine o’clock each morning, he would arrive at Kenley Railway Station, where he would be met by a pony and trap, and driven to The Welcomes. He would spend the day there, and be driven back to the station at about six o’clock.

Then, one night in April 1921, the farmhouse burnt down. Dyer, with his wife and children, moved in over the stables – and he also moved in with a swift claim against the insurance company.

The place had cost £5000. Dyer had insured it for £12,000. Suspicious after a sharp-eyed insurance inspector had spotted a number of petrol tins, the company declined to settle. And Dyer was shrewd enough not to press his claim.

After the fire, no more business was conducted at the farm, and Dyer was beginning to cast around for ready cash. His tanglings with fast women and slow horses were proving expensive. He needed money. At first he obtained it by borrowing from Tombe. Then he forged his partner’s name on several cheques. Discovery, accusations and a bitter quarrel followed.

The new year – 1922 – started badly. Three months went by without much improvement. Then Tombe simply vanished from the face of the earth. The last trace that anyone had of him was a letter. Addressed to his parents, it was dated Tuesday, 17 April. ‘I shall be coming to see you on Saturday,’ it said.

Eric Tombe never arrived.

In their little house in Wells Road, Sydenham (seven miles north of Kenley), the Reverend George Gordon-Tombe and his wife watched for the postman, listened for the doorbell, waited for some word of their son. The weeks lengthened into months. Puzzled, plagued with anxiety, the frail, sixty-year-old, retired clergyman turned detective. He began putting advertisements in the personal columns of the papers. No reply. He spent three months scouring the West End for clues. Drew blank after blank. Just as he was starting to despair of ever finding out anything, his luck changed.

‘I went to see a barber, Mr Richards of the Haymarket, to ask if he had seen my son lately. He told me no, not for a long time. But as I was leaving the shop, a thought struck me to ask if Eric had ever brought any friends there. The barber kept a little book in which he recorded any introductions by his customers. In it was written: ‘Ernest Dyer, The Welcomes, Kenley. Introduced by Mr Eric Tombe.’

The name Dyer meant nothing to the retired clergyman, but he lost no time in paying a visit to The Welcomes. Dyer was not there, but his wife was. She could tell him nothing definite, but was able to give him an address in Yorkshire where, she said, a close friend of his son’s lived. Mr Tombe left at once for Yorkshire.

There he heard a tale that seemed to confirm his worst fears. The daughter of the house said that she had last seen Eric in March 1922. He had arranged to meet her and another young woman, to whom he was engaged, at Euston Station on 25 April. Dyer was to meet them there, too, and the four of them were to take a brief trip to Paris. When they arrived at Euston, however, Dyer was on his own. He showed them a telegram which he said had come from Eric – ‘SORRY TO DISAPPOINT. HAVE BEEN CALLED OVERSEAS.’

That word ‘overseas’ had aroused one of the girls’ suspicions. ‘It wasn’t one of Eric’s expressions,’ she said. ‘He never used it. But Dyer did.’ And she told Dyer point-blank, I don’t believe that telegram is genuine. I think you’ve made away with Eric, and I shall go straight to Scotland Yard.’ Dyer became very agitated. ‘Don’t do that,’ he pleaded. ‘If you do, I shall blow my brains out.’

The Paris trip was called off.

Thoroughly alarmed now, Mr Tombe caught the next train back to London, where he went to see the manager of his son’s bank. ‘I don’t think you need to worry,’ the manager told him. ‘We have a letter here which was written by your son only last month.’

The letter was dated 22 July 1922. Mr Tombe scrutinised it closely.

‘That is not my son’s signature,’ he said. ‘This letter is a forgery.’

The manager’s turn to look worried. Rapidly he leafed through Eric Tombe’s file.

| April 1922 | Credit balance £2570. Letter from Tombe requesting transfer of £1350 to the Paris branch, and asking that his partner, Ernest Dyer, be allowed to draw on it. |

| July 1922 | Letter from Tombe notifying that he had given power of attorney to Ernest Dyer. |

| August 1922 | Tombe’s account substantially overdrawn. |

When Mr Tombe left the bank, he was absolutely convinced that Ernest Dyer was not only a forger and a thief – but also a murderer.

But where was Ernest Dyer? His wife didn’t know. He had not been seen at The Welcomes for months. He had vanished as totally and mysteriously as Eric Tombe.

The time Three months later. 16 November 1922.

The place The Yorkshire seaside town of Scarborough.

Mr James Fitzsimmons is just finishing his lunch in the dining-room of the Old Bar Hotel when he receives a message that there is a gentleman asking to see him.

The gentleman is Detective Inspector Abbott of the Scarborough CID, and he is anxious to ask Mr Fitzsimmons a few questions regarding a number of dud cheques which he has been passing. He is also requiring an explanation concerning an advertisement which Mr Fitzsimmons has inserted in the local papers, inviting men ‘of the highest integrity’ to contact him with a view to obtaining employment with exceptionally good prospects. All they had to do was to produce a substantial cash deposit to establish their probity. It was one of the oldest tricks in the confidence business.

Mr Fitzsimmons is all charm and plausibility. ‘Of course, of course, Inspector. Now, if you will just step upstairs to my room, I’m sure we can clear this matter up to your entire satisfaction.’

It was as they reached the landing that Abbott saw Fitzsimmons make a suspicious movement towards his pocket. Thinking that he was about to destroy some incriminating evidence, Abbott seized hold of him.

There was a struggle. The two men crashed to the ground. A flash … an ear-splitting explosion. Fitzsimmons went limp. The bullet from the revolver he had pulled from his pocket had killed him instantly.

Later, when the police searched Fitzsimmons’s room, they discovered a suitcase bearing the initials ‘E.T.’. They found, too, a passport in the name of Eric Gordon-Tombe – and 180 cheque forms, on each of which was pencilled Tombe’s forged signature.

James Fitzsimmons was Ernest Dyer.

But where was Eric Tombe?

Dyer had been dead and buried ten months on the day that the Reverend George Gordon-Tombe called at Scotland Yard.

Superintendent Carlin sat at his big desk and listened politely to the incredible story that the clergyman was telling him of his wife’s recurrent nightmare. Night after night, he said, Mrs Tombe had had the same terrifying dream. In it, she saw her son’s dead body lying at the foot of a well.

Carlin was sympathetic – but dubious. Dreams are not evidence in the matter-of-fact world of crime detection. Yet somehow, as Mr Tombe talked on, telling the detective of his own investigations, the dream seemed to take on a significance.

At length, Carlin leaned back in his chair. ‘Very well, Mr Tombe,’ he said. ‘We’ll look into the matter.’ A day or two later, when Carlin and his men went down to The Welcomes, he discovered something that sent a shiver down his spine. There were five disused wells in the grounds of the farm.

Carlin remembered Mrs Tombe’s dream. Perhaps a mother’s intuition had probed beyond the veil. Ridiculous? Well, let’s see. He gave the order – ‘Dig.’

The autumn moon hung low over the stark, fire-blackened rafters of the gutted farmhouse. Somewhere away in the distance, a dog was howling. Otherwise, only the scraping of the spades on stones and the heavy breathing of the diggers broke the stillness.

Suddenly one of the men called out: ‘We’ve come to water here, sir.’ Then, as the glow of the lowered lantern tinctured the oily black surface twelve feet down, they saw, sticking out of the mud, a human foot.

Hours later, at Bandon Hill mortuary, near Wallington, Tombe’s father looked at the body – at the stained clothes, the gold wrist-watch, the tie-pin, the cuff-links. Tears were running down his face as he whispered: ‘Yes – yes. That is my dear boy.’

A pathologist discovered a gun-shot wound, about 1¼ inches in diameter, at the back of the head. He thought that it was probably caused by a shotgun, fired at close range.

What actually happened at The Welcomes must remain for ever a mystery. Not even the date of the murder is known. The coroner’s jury put it as on or about 21 April 1922, but that was mere guesswork.

Carlin had his theories, though. He believed that Dyer had lured Tombe to The Welcomes and, in a tumble-down shed near the paddock, crept up from behind and shot him in the back of the head. He had left the body in the shed, returning later to stuff it down the well and fill the well with stones.

This theory was partly confirmed by a subsequent conversation with Dyer’s widow. She told how, at about eleven o’clock one night, she was sitting alone at The Welcomes, when she heard the sound of stones dropping against the drainpipe. She called to her dog and opened the front-door. As she peered out, the dog started to growl and bristle. The moon was up, but big black clouds scudding across the sky plunged the yard into alternate silvery light and thick darkness. Suddenly, barking savagely, the dog dashed towards a disused shed in the corner of the yard and flew at someone crouching in the shadows. A man emerged, and at that moment a stream of moonlight flooded full on his face. To her astonishment, she saw that it was her husband, whom she had believed to be miles away, on business in France. Deathly pale and trembling, he held up his hands, shouting, ‘Don’t come in here. Don’t come out. Get into the house again, for God’s sake.’

Nearly seventy years have gone by since Tombe and Dyer perished – both by the same hand. But The Welcomes still stands.

When, some years ago, I went there, it was a peaceful scene. The wells had long since been filled in. Nothing remained to hint at the old tragedy.

Over a cup of tea in a luxuriously-furnished room above what were once the stables, the then occupant, the widow of Charles Pelly, the pilot who flew Neville Chamberlain to Munich on his ‘Peace in Our Time’ flight to see Hitler in 1938, told me: ‘The Tombe tragedy wasn’t the only one connected with The Welcomes, you know. In 1934 a Major St John Rowlandson shot himself in a taxi as he was being driven through St James’s Street. I think he was in some sort of financial trouble. He lived here with his sister.’

But it was the Tombe case that was remembered in those parts. ‘Even today,’ said Mrs Pelly, ‘local boys peer through the gate and recall “Eric down the well”.’

What are the odds against anyone dreaming the same circumstantially accurate dream night after night, as the clergyman’s wife did? If it was no more than chance, then they are odds so high that it is virtually impossible to calculate them.

And was it not passing strange that a hard-headed policeman should, acting on the ‘evidence’ of a mother’s prophetic dream, come to solve what might well have remained a mystery for ever?

Had Sherlock Holmes turned to the planets for help when unravelling some of his more celebrated murder-cases, we might today be surrounded by dozens of star-gazing ‘astrosleuths’, each as eager to seek clues in a suspect’s birth-chart as in the bloodstained clothing found under the floorboards. But despite a life-long interest in the paranormal, Conan Doyle never let his pipe-smoking hero examine a single horoscope. And what a pity. For if he had, Sir Arthur might have forged some useful links between astrology and the law.

Holmes, of course, confined his detective work to the fiction shelf; but much can be said for the use of astrology in real-life murder investigations as well, for no matter how carefully a killer may try to cover his tracks, there is always one piece of evidence he can never destroy: namely, the positions of the planets at the time of his crime.

Which brings us to the Dyer-Tombe case. Did Ernest Dyer actually kill Eric Tombe? And if so, is there any evidence – any planetary evidence, I mean – to confirm that fact?

Before looking at what the planets have to tell us (and by tradition the Sun and Moon are called ‘planets’ as well), I should explain that in astrology one normally works with at least three sets of planetary positions: the ‘natal’ positions (those degrees of the zodiac occupied by the planets at the time of a person’s birth); the ‘progressed’ positions (those degrees occupied by the planets during the days immediately following birth, where each day represents one year in the individual’s life); and the ‘transiting’ positions (the actual day-to-day positions of the planets at any given time).

Since the planets act as the principal words in the language of astrology, every person, object or event encountered in life can be expressed by the appropriate ‘signature’ or combination of individual planets. Murder, for example, is commonly indicated by the ‘vulgar’ (Hades) ‘acts’ (Mars) combination of Mars and Hades (one of the eight transneptunian ‘planets’ discovered by Alfred Witte and his colleagues at the Hamburg School of Astrology), with Saturn or Uranus also frequently appearing as part of the signature.

To create a signature, the planets involved must be properly linked together. A link is formed, for example, whenever the distance between two planets is either an exact whole-number fraction of the full 360° zodiac or a whole-number multiple of that fraction, or whenever a planet is positioned either on the ‘midpoint’ (or halfway point) of two planets or at one of those same fractional distances from that midpoint. Thus, planets that are 45° apart (⅛ of 360°) or 135° apart(⅜ of 360°) will be linked together, as will any three planets, one of which is positioned either 30°( ) 60° (⅙), or 72° (⅕) away from the midpoint of the other two.

) 60° (⅙), or 72° (⅕) away from the midpoint of the other two.

Now, if Ernest Dyer killed Eric Tombe (as the circumstantial evidence strongly suggests), then we ought to be able to find at least one Mars-Hades ‘murder signature’ in Dyer’s chart at the time of Tombe’s death. Ideally, such a signature should also be linked to Tombe’s natal or progressed Sun – that is to say, to either the Sun’s position when Tombe was born or (since Tombe was 29 ½ years old when he died) to its position 29½ days after he was born – in order to identify Tombe as the murder-victim.

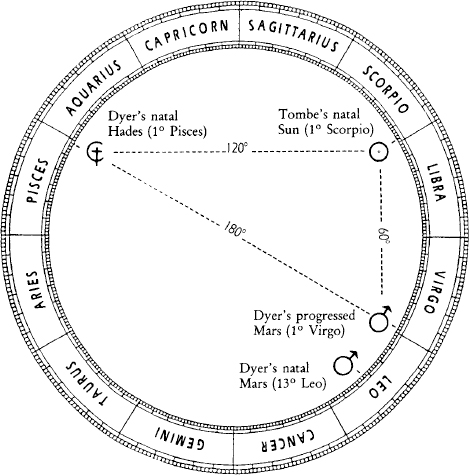

Surprisingly enough, a link does turn up in Dyer’s chart between Tombe’s natal Sun (1° Scorpio) and Dyer’s natal Hades (1° Pisces), for those two planets are exactly 120° (½ of the zodiac) apart. But Dyer’s natal Mars (13° Leo), needed to complete the Mars-Hades ‘murder’ signature, is not directly connected to either of those planets.

The investigation, however, does not end there. If we calculate the position of Dyer’s progressed Mars for the spring of 1922, note what turns up: at the time of Tombe’s murder, Dyer’s progressed Mars (1° Virgo) was exactly 180° (½ of the zodiac) away from Dyer’s natal Hades and 60° (⅙ of the zodiac) away from Tombe’s natal Sun, thus creating the ‘murder’ signature linked to Tombe’s Sun that we were looking for (Fig 1). To the astrologer, such evidence is as incriminating as the discovery of Tombe’s suitcase in Dyer’s possession in Scarborough.

Fig 1

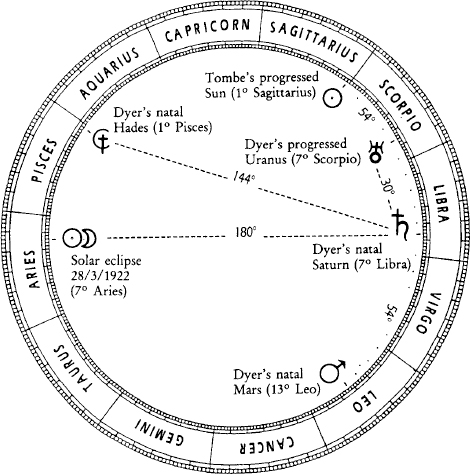

Fig 2

But there is still more evidence to be found against Dyer. In his chart, natal Saturn (7° Libra) is linked to natal Hades (the distance between them is 144° or ⅖ of the zodiac) and at the time of Tombe’s death was also linked to Dyer’s progressed Uranus (30° away at 7° Scorpio). Had Dyer’s natal or progressed Mars been part of this same pattern, we would once again have a potentially dangerous ‘murder signature’ on our hands – but Dyer’s natal Saturn fails to reveal any obvious links to either of these Mars positions. However, if we measure the distance in his chart from natal Mars to natal Saturn, and similarly measure the distance from natal Saturn to the position of Tombe’s progressed Sun (1° Sagittarius) in 1922, note what we discover: those two distances (54° each) are exactly the same – thus placing Dyer’s natal Saturn (7° Libra) directly on the midpoint (7° Libra) formed between his natal Mars and Tombe’s progressed Sun at the time of Tombe’s death (Fig 2). In other words, Tombe was killed precisely during that one brief period in his life when the position of his progressed Sun would complete the Mars-Saturn-Uranus-Hades ‘murder pattern’ in Dyer’s horoscope.

An ephemeris for 1922 (listing the daily positions of the planets) indicates that a solar eclipse took place in March of that year, less than a month before Tombe’s death. The ancient astrologers feared eclipses, for they tend to act as powerful ‘triggers’ for any planets or planetary signatures to which they are attached. (For instance, the 15 January 1991 deadline set by the United Nations for the withdrawal of Iraqi troops from Kuwait fell on the day of a solar eclipse [at 25° Capricorn] that was directly linked to the position of Mars [the planet most commonly identified with weapons and warfare] in President Bush’s natal horoscope.) It therefore comes as no surprise to find that the March 1922 solar eclipse fell at 7° Aries, exactly opposite (that is to say, 180° away from) Dyer’s natal Saturn, thus linking the eclipse-point to the entire cluster of planets (Mars, Uranus, Hades, and Tombe’s progressed Sun) attached to Dyer’s natal Saturn at that time!

If we knew the precise time of Dyer’s (and of Tombe’s) birth, we could possibly determine the exact day (and perhaps even the time of day) that Tombe was killed. In the absence of that evidence, we can note that Tombe was most likely murdered some time between 17 April (the date of his letter to his parents) and the 22nd (when he failed to keep his appointment). And we can further note that on Wednesday the 19th, the ‘murder midpoint’ between transiting Mars and transiting Hades was exactly aligned with the ‘thinking about Tombe’ midpoint formed by transiting Mercury in combination with Tombe’s progressed Sun. This could easily have been a day on which Dyer thought seriously about killing Tombe, and may even have been the actual day that Dyer, eager to get his hands on Tombe’s money, pointed a gun at Tombe’s head and pulled the trigger. The exact time of the murder may never be known, but there can be little doubt (astrologically speaking) about the identity of Tombe’s killer.