|

THE ARTS AND CRAFTS MOVEMENT |

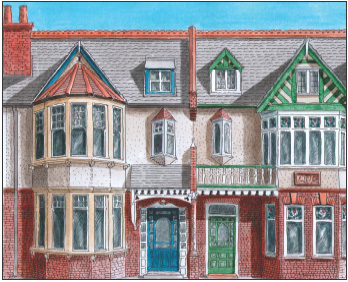

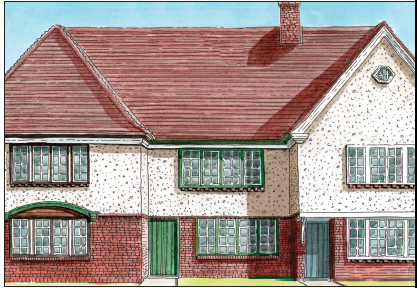

FIG 1.1: The Arts & Crafts movement was instrumental in bringing the countryside into the town and shaping the distinctive housing estates of the first half of the 20th century.

A true Arts & Crafts house is one where traditional materials, techniques and styles from the local area (vernacular) were used to create a building of good quality and simple form, in which the function of the interior spaces was as important as the shape of the exterior. The architect was usually involved in the design of every detail, from the structure down to the handle on the front door, while craftsmen hand-made the decorative details used to enliven the surface of the house, which relied upon variety in texture of materials to break up their otherwise plain form. Although some houses have been built to this strict doctrine over the past 150 years and can rightly be described as Arts & Crafts style, the buildings that are usually referred to as such were mainly erected from the 1870s to the early 1900s by architects working loosely under the banner of the Arts & Crafts movement and are described in detail in Chapter 2.

By their very nature of being custom-designed and hand-made, these houses were very expensive and were usually reserved for the upper middle classes. Attempts to create homes for the masses using some of these principles were made most notably in workers’ estates linked to factories like Port Sunlight and Bournville or later at Letchworth Garden City. However, for the majority, their terraced houses were built to standard forms with little expression of style. For those who could afford to pay a little more rent (few homes were owned in this period) the builder could mask the brickwork or add mass-produced details to imitate the Arts & Crafts houses, a fashion that became widespread in the early 1900s. It is the terraces, semis and detached houses built in social housing schemes or by speculative builders, dating from 1870–1914, that today are often referred to as Arts & Crafts and although not strictly true in origin are still of note and hence are covered in detail in Chapter 3.

FIG 1.2: A fine detached Arts & Crafts style house with a rendered exterior broken up by exposed stonework, tall plain chimneys and a distinctive long, low mullion window. Although plain compared with the busy Gothic piles that preceded it there was still scope for homely features such as bow windows, colourful patterned glass and low-slung tiled roofs.

FIG 1.3: An end terrace house built in the Arts & Crafts style as part of a large workers’ estate, with its form, plan and fittings designed by an architect for this specific site. Note the mix of render, brick and stone and the decorative rainwater trap.

Arts & Crafts is today a broad banner often used to describe buildings that at the time had little to do with the movement. Most architects in the late 19th century were inspired by timber-framed farmhouses, old stone manor houses and late 17th-century brick structures, a domestic revival led by influential men such as Richard Norman Shaw (many Arts & Crafts architects started work in his practice) creating Old English, Queen Anne and Neo-Georgian styles. The details from these contemporary styles were often jumbled up by speculative builders, and some of the features that are distinctive of this period, like decorative plaques, mouldings and bargeboards, are included in the Arts & Crafts style illustrations in Chapter 4.

FIG 1.4: Part of a row of mass-produced terrace houses onto which the speculative builder has added details from various sources, including the Arts & Crafts style, as was typical in the 1890s and early 1900s. Rendered first floors, timber-framed gables, muscular bow windows and terracotta plaques were common.

The Victorian age was more complex than it first appears. Fortunes fluctuated dramatically, factories appeared indiscriminately and an Empire born out of commerce became a national obsession. Society maintained its order, with an aristocracy actively involved in trade and industry staving off the revolutions that swept across Europe in the early 19th century, partly by empowering the middle classes with the vote so that they became a dominant group in their own right, with aspirations to emulate their social superiors. The mass of the working population, which accounted for up to four out of every five people, had to wait until the closing decades of Queen Victoria’s reign before they were enfranchised, and that only happened when fear of an uprising and the growing power of trade unions had provoked those above into action. Through all levels of society there was a general acceptance of a Victorian doctrine that individual effort and high moral values were key to progress, self-help was the order of the day and the authorities prided themselves on minimum interference in trade and industry.

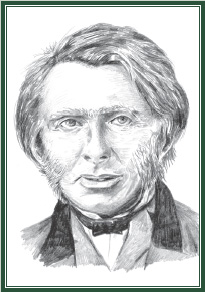

FIG 1.5: Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812–1852) was one of the first to study medieval buildings in detail and identify Gothic as an indigenous style that was more honest and appropriate than those from the Ancient World. He designed churches and buildings like these at Cotton College, Staffordshire, making red brick and the pointed arch fashionable once again. His writings and studies of Gothic architecture were hugely influential to the architects and designers who would follow and who in turn went on to inspire the Arts & Crafts movement, although Pugin died at the tragically young age of 40.

When Victoria came to the throne the country, which had boomed in population and global influence, was searching for a cultural identity, one that would be separate from the European styles that had dominated domestic art and architecture for centuries. Men of taste argued between Classicism and Gothic, a battle of styles that was ultimately won by the latter, especially after it was chosen as the theme for the new Houses of Parliament. These were in part designed by Augustus Pugin, the most learned and passionate advocate of Medievalism. The hugely influential critic John Ruskin had preached the value of these domestic historic forms on moral as well as aesthetic grounds. The obsession with the pointed arch was further crystallised by declining outside influence; no longer did wealthy young men travel to Europe on grand tours to study the wonders of the ancient world and import foreign pieces of art and architectural styles. Now they were posted to the far corners of a growing Empire in which British morals and taste were exported to its subjects. This created a sense of isolationism and distrust of anything Continental in the second half of the 19th century. Those who absorbed new European culture, like Oscar Wilde, were viewed as immoral, and impressionist artwork by masters such as Van Gogh, Cézanne and Gauguin was publicly derided when exhibited here in 1910.

FIG 1.6: John Ruskin was the most influential cultural icon of his generation, a highly articulate writer and thinker who guided painters, architects and designers on the approach and execution of their work, paying special attention to the close study of nature. He promoted the Gothic style as it represented what he thought to have been a more moral and deeply religious time; his love of this mystical Middle Ages partly encouraging others to reject machines and industry and look to a home-grown rustic past for inspiration. Ruskin also linked art and morality, laying the seeds for its close association with Socialism, the re-emergence of the traditional craftsman and the importance of the artist being involved in every aspect from design to construction. His most notable book, The Stones of Venice, was studied closely by many who went on to influence the Arts & Crafts movement.

There were also problems with industry. Despite the country being at the forefront of technology, in the early 1800s criticism grew about the quality of goods and exports dropped, encouraging the government to look into the matter and conclude that a lack of training in design was the root cause, with national schools for the arts being established in response. There was also a growing awareness of the plight of those who kept the wheels of industry turning. The long hours and lack of support when work dried up meant that employees in factories and mines often faced poor living conditions and destitution, with little opportunity to escape. The rumbling of discontent empowered the fledgling Socialist movement and encouraged the authorities to establish museums, libraries and schools to educate and inspire the working classes, and the widespread literacy by the end of the century created a boom in the popular press and magazines.

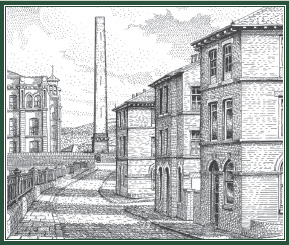

FIG 1.7: SALTAIRE, WEST YORKSHIRE: When building his new mill alongside the River Aire near Bradford, Titus Salt established a small village with quality housing for his staff. Saltaire, named after himself and the river that powered his mills, was a revelation and was copied and improved upon by others like the Cadburys at Bournville and Levers at Port Sunlight later in the century.

Since the late 18th century there had been a growing interest in home-grown history. Ruined abbeys and castles were appreciated for their dramatic and picturesque settings and tales of medieval chivalry made popular reading. This rather rose-tinted view of the past combined with isolation from European culture, the discontent felt by many about the effects of factory conditions upon the labouring classes, and the perceived poor quality of mass-produced goods led some Victorians to look back to the way of life and buildings of the Middle Ages for an answer to the present-day ills. By the 1850s, romantic anti-industrialism and a growing appreciation for nature and the countryside could be found expressed in the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood of artists who produced stunningly detailed paintings inspired by Ruskin’s belief in the accurate study of flora and fauna, and in the buildings of the Gothic revival led by Pugin’s energetic but shortlived output of churches, houses and interiors. There was one giant of a figure, however, who emerged at this time, putting many of these theoretical threads into practical use, a multi-talented artist, social reformer and powerful orator who revolutionised design and inspired a future generation, William Morris.

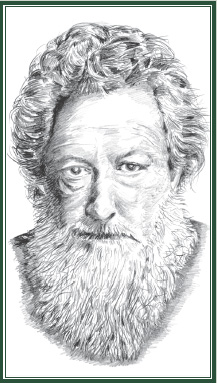

Seen by many as the father figure of the Arts & Crafts movement, he was not only a guiding light to the guilds and groups that were established under its banner but also – due to his incredible range of talents – someone who had contact with many of the key figures in architecture, art, literature and design at the time. William Morris was born into a wealthy middle class family in March 1834 and was educated at Marlborough College and then Exeter College, Oxford, where he met Edward Burne-Jones, a fellow artist and designer who would remain a lifelong associate. The two young men, fuelled by an appreciation of Ruskin’s book The Stones of Venice, established themselves in Bloomsbury in 1856 where they shared accommodation with Rossetti, the Pre-Raphaelite painter, with Morris working for a time in the practice of the architect G.E. Street. Here he met Philip Webb, who designed for him the Red House, the Bexleyheath home that Morris and his new wife would move into in 1860.

Although Morris had ambitions to be an artist, his self-critical view of his paintings and the founding of Morris, Marshall and Faulkner in 1861 encouraged him to abandon that course and concentrate on design, with the company, which would become Morris and Co, expanding its scope to include stained glass, wallpapers, fabrics and tiles. At the same time he became a leading poet, held in such high regard that he was even considered for the position of Poet Laureate after Tennyson. As the company grew in stature and Morris’s free-flowing designs of flora and fauna became appreciated, especially amongst a booming suburban middle class, he sought even greater perfection in its products, which avoided the use of modern materials. He spent a number of years from 1875 visiting Thomas Wardle’s dye works in Leek, Staffordshire, to try to find a wide range of colours for fabrics, using natural ingredients and traditional methods, a key part of his design work. It was while he was in this industrious little mill town that he came face to face with the factory system he had despised from a distance. He was now inspired to speak out publicly against it and become a key figure in the early Socialist movement.

FIG 1.8: William Morris was not only a talented designer, poet and artist but also a visionary who helped break down the barriers between fine art and handmade crafts and revolutionised the approach to design. He was one of the first educated men who was happy to get his hands dirty, not passing on any job in his workshop that he would not have been able and prepared to do himself and promoting his belief that designers should be involved in all aspects of the production of their work, and that art was key to improving the quality of goods. He encouraged others to form collectives, believing that the mutual support from a group based upon medieval guilds would aid production. Unlike many of his contemporaries, he was a practical man who turned much of this theory into a successful business, and he looked forward to a day when ‘the millions of those who sit in darkness will be enlightened by an art made by the people and for the people, a joy to the maker and the user’.

FIG 1.9: RED HOUSE, BEXLEYHEATH, KENT: Two faces of this revolutionary house by Philip Webb, which had an asymmetrical plan, stylised Gothic forms and vernacular features. Despite his love for the place Morris moved out in 1865 as the commuting from here to the company studios 12 miles away in central London was taking three or four hours a day!

FIG 1.10: While he was working in the Staffordshire mill town of Leek, Morris became aware of the problems created by the factory system and the poor conditions workers had to endure. The town today has many houses built in the late Victorian and Edwardian period, inspired by the Arts & Crafts movement, which he helped establish, among them these workers’ cottages connected with the Co-op (the left-hand one was originally a shop).

In his later years with Morris and Co, a household name, he spent more time at Kelmscott Manor in the Cotswolds, a house he had rented (but never owned) since 1871 and which became a focal point for family and associates, although never the artistic commune he had longed for since his time at the Red House. When he died in October 1896 his obituary referred to him principally as a writer and poet. However, it was his linking of art to social reform and the practical benefits he believed came from empowering workers to design and create their own products – a return to pre-industrial craftsmanship – that were of greater influence. This was especially true to a new generation of designers and architects who during the 1880s and 90s began founding guilds and groups based around his ideals and under the banner of the Arts & Crafts movement.

Several threads come together in the Arts & Crafts movement in the last decades of the 19th century. The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had shown how a collection of artists could work under a single banner with similar beliefs and aims while the Aesthetic movement in the 1870s had rejected commercialism and moralising and sought beauty and sensation in the arts, with the focus upon colour, tone and texture. These sources of inspiration encouraged young artists, designers and architects, clutching their books by John Ruskin and fuelled by the writings of William Morris, to seek a new approach to their work. In effect, they became craftsmen, raising the status of decorative products carved, turned, or polished by hand to that of the fine arts, but at the same time finding beauty in their simple form and functional efficiency. Whether it was a house, furniture or simple fittings, they would usually be involved from the original design through to the finished article, with an emphasis upon using traditional methods and materials and with close association to the countryside and nature rather than industry and the city.

Many formed themselves into collectives based upon the ideals of brotherhood and artistic communes that Morris had sought. One of the earliest was the Art Workers’ Guild, formed in 1884 by Ernest Newton, W.R. Lethaby, Edward Prior, Gerald Horsley and Mervyn Macartney, all of whom had worked in the architectural practice of Richard Norman Shaw. This brotherhood of artists, promoting the equal status of all forms of art, tripled its membership to around 150 after only six years. In 1888 the guild set up a separate organisation to act as its public face, the Arts & Crafts Exhibition Society; its name being used afterwards for the movement as a whole. Another influential group was founded by C.R. Ashbee in the same year, the Guild and School of Handicraft, at first in the East End of London but later moving out to Chipping Campden in the Cotswolds. Ernest Gimson and Sidney Barnsley took it a stage further by establishing an artists’ commune in the tiny Gloucestershire village of Sapperton, with the new houses to the north and east of the existing settlement built with such respect to local styles and materials as to be hardly distinguishable from their older neighbours. Regional guilds were established in the early 1890s and a Central School for Arts & Crafts in 1896, so that by 1900 there were probably over a hundred separate groups working within the movement. Other architects and craftsmen preferred to work on their own, and although tied into the movement by similar artistic ideals they may have had less interest in its social reforming aspects.

FIG 1.11: A hall and church built in an Arts & Crafts style with the distinctive simplified vernacular forms and rows of short windows, which were plain enough to be modern in appearance. Some features like the eyebrow dormer window (right) and the angled wings with their narrow slits (left) demonstrate the inventiveness of many architects working under the Arts & Crafts banner, a term that did not come into widespread use until the end of the 1890s, shortly before these buildings were designed.

There were problems, however, with some of these high-minded ideals right from the start. William Morris had been held up as a champion of the movement by many of its guilds but he had reservations about their practical success and had little involvement with them, seeing their establishment as doing little to solve the problems created by the factory system, issues in which he was passionately interested. Although today we might find his own solutions to the problems – turning the clock back to a mystical past – to be backward and simplistic, he was always aware of the need to combine the role of the craftsmen with the machine and of the practical economics of business, as he had demonstrated with his successful company. His ideal was for a time when nothing made either by hand or machine would ‘be ugly, but will have its due form, and its due ornament, and will tell the tale of its making and the tale of its use’.

The work produced by the Arts & Crafts movement with its avoidance of mass production became, by its very nature, expensive, being commissioned or bought by wealthy and artistic members of the middle classes. C.R. Ashbee stated with resignation when the Guild and School of Handicraft was wound up in 1908 that ‘we have made of a great social movement, a narrow and tiresome little aristocracy working with great skill for the very rich’. W.R. Lethaby also saw problems with their rejection of the machine, stating ‘we have passed into a scientific age, and the old practical arts, produced instinctively, belong to an entirely different era’.

The beautiful, simple and high-quality buildings and products made by the movement can still be appreciated today but of more far-reaching influence was the doctrine of form and function in design, an appreciation of historic styles and the countryside and the unification of all types of art. German-speaking countries embraced the work of Arts & Crafts designers, Muthesius promoted the English house and the Secession Group founded in Vienna in 1897 and Wiener Werkstatte of 1903 were influenced by the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Ashbee and claimed kinship with Morris. In America their own Arts & Crafts movement developed, with leading figures like Frank Lloyd Wright, who used the style of the Shakers and indigenous peoples for inspiration in his buildings, but although they remained close to nature in essence they did not turn their back on the machine, making their products available to a wider market. In Europe similar Arts & Crafts groups were formed, the writings of Morris and the work of Mackintosh being two of the rare contributions to Continental culture from Britain in this period. Some of the founders of the Modern movement that evolved after the First World War echoed the views of Arts & Crafts designers, who helped shape its initial ideals, in effect bridging the architecture of the 19th and 20th centuries.

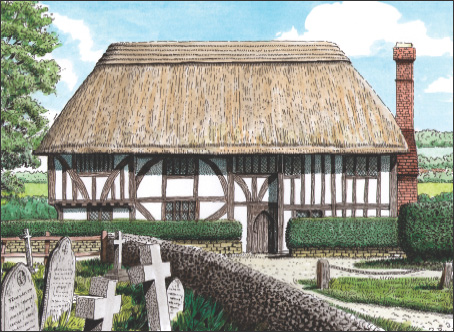

FIG 1.12: William Morris and other members of the Arts & Crafts movement were also involved with founding the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings, which sought to counter vigorous Victorian restoration that destroyed much of what they were meant to be preserving. They were also key in helping to found the National Trust, its first acquisition being Alfriston Clergy House, East Sussex, in 1896 (pictured here) a Wealden-type, timber-framed structure that was just the type of building to have inspired many of the architects involved in the movement.