‘To every action there is an equal and opposite reaction.’ This golden rule of physics would have found resonance with the leading figures in Victorian culture. A nation whose apparent glory had been founded upon groundbreaking industrial developments and inventive entrepreneurs was very adept at masking the effects of such rapid change – a dark underbelly of social discontent created by poor living conditions, long working hours and a monotonous factory system. In response to this, a new generation of social reformers, architects and designers sought in the latter half of the 19th century to restore dignity and pride to workers and create buildings and objects of simplicity and beauty based upon an idealised medieval world. The Arts & Crafts movement, as it would become known, began a revolution in design and drew attention to the plight of industrial workers but it was the houses that its adherents built and the fittings they crafted that are their most distinctive and notable contribution.

Yet, unlike other styles based upon an easily recognisable architectural feature or rule, Arts & Crafts buildings can be found with many sources of inspiration and no single detail common to them all. One of the movement’s characteristics is the inventiveness of its exponents, who not only created modern forms based upon a wide variety of historic styles but also used the surrounding landscape and the demands of the interior to shape the structure of the houses so that no two are alike. Identifying them is made all the more complicated because, in addition to the designs of the leading independent designers, there were hundreds of local architects producing work inspired by them and thousands of speculative builders applying their fashionable details to standard terraces and semis. Despite this, there are some key characteristics that were shared by many of those working in the movement, and contemporary features and regulations that can help with dating a building and make their revolutionary designs stand out from the majority of Victorian and Edwardian housing.

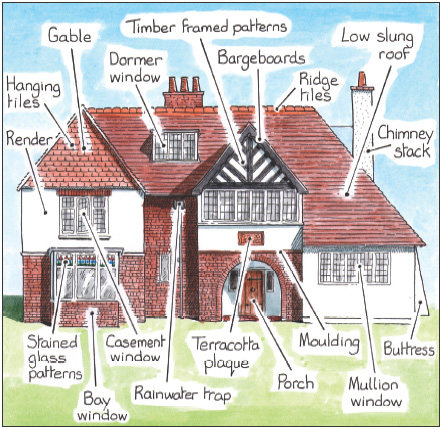

This book sets out to explain the background, introduce the most notable architects and show, using clearly labelled illustrations and photographs, what makes Arts & Crafts houses different from others produced in this period. The first chapter defines the basic rules that link them, the significant figures who inspired the formation of the movement and its effect upon contemporary and later culture. The second chapter looks at the work of the leading architects, giving a brief biography of each and examples of their work, along with a more detailed description of the style. The next chapter describes the attempts to produce large-scale estates within the ethical rules of the movement and helps the reader to differentiate the work of famous architects from those buildings today referred to as ‘Arts & Crafts’ but which are usually mass-produced housing, with fashionable fittings and materials added to standard structures. The fourth chapter has photographs of distinctive features and details that can help identify the style and aid renovation, while the final part looks inside at the rooms and the decoration that so revolutionised interior design.

For anyone who simply wants to recognise the style, understand the contribution of key characters and appreciate what makes Arts & Crafts houses special, this book offers an easy-to-follow introduction to the subject. If the reader is fortunate enough to own such a house, then the illustrations and text will hopefully assist any planned renovation or redecoration while the list of places to visit and contacts at the end can help take any studies further. For those of us who can but look on and admire, I hope the book helps clarify the true essence of the style and why it is such a unique and valuable contribution to a street, a community or even a town, one which should be better appreciated and lovingly protected.

Trevor Yorke