“He who is not everyday conquering some fear has not learned the secret of life.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

A few months after arriving in the Hanoi Hilton, an English-speaking turnkey casually delivered copies of a three-page biographical questionnaire to our cell and told each of us to fill one out. It contained detailed questions about family, socioeconomic background, education, and military experience, including assignments and training. If accurately completed, these biographies could give our captors valuable insights they could use for propaganda and psychological warfare. They would also reveal who among us might have had access to sensitive military information. When the turnkey returned to pick them up, we told him that we were providing the basic information required under Geneva Convention, but no more. He left in a huff.

We waited anxiously, knowing that they were not going to let us off the hook. The next day when we heard the keys rattling outside our door at an odd time in the daily schedule, my stomach tightened in a knot. The door opened and our regular turnkey Sweet Pea motioned for Ken and me to suit up into our long-sleeve black pajamas. Then he took us out separately to different interrogation rooms. It was again time to confront my doubts and fears.

The interrogator took the “I’m your friend” approach. After politely asking me some questions about my living conditions and health, “Good Buddy” (our nickname for him) said in a reassuring manner, “I understand you may not want to fill out the questionnaire, but as your friend I advise you to do it. It’s a camp requirement. You are a ‘creeminal’ and must obey all orders of the camp officers.”

When I again refused, Good Buddy suddenly transformed before my eyes. His voice became shrill, the veins popped out on his head and neck, and he yelled, “If you do not obey my orders, another man will come and torture you very badly!” I still refused, so he ordered me to sit on a small stool; then he left me alone in the room to think about it.

After an hour or so, Good Buddy returned and again ordered me to comply. When I refused, guards shackled my legs and forced me to get down on my knees with my arms over my head. I was warned that if I moved from that position, I would be beaten. It didn’t take long before my knees and muscles were in agony and my arms felt like lead. About three hours later, Good Buddy returned and threatened me with “terrible torture, even electric shock to the heart.” I was then left alone in the stress position to reconsider. In the hours that followed, I had to battle minute by minute with all my strength against two enemies: my captors and my internal doubts and fears.

During the long night I often had to lower my arms or sit down. When the guards caught me, they kicked me and forced me back into position. Although this type of torture was no doubt preferable to the harsher alternatives, I could see why the V used it. In addition to leaving no marks on the body, it forced us in a manner of speaking to inflict the torture on ourselves. I knew they were to blame for this inhumane treatment, but I could not escape the fear that at some point I also would be guilty too, if I was not strong enough or tough enough to endure the pain I was inflicting on myself.

Around 6:00 a.m. a new interrogator entered the room and ordered me to complete the form. When I refused, he told the guard to stay with me and beat me whenever I moved out of the stress position. Around 8:00 a.m. I dropped to the floor, too exhausted to remain in position. The guard began kicking and hitting me with increasing intensity. Finally I yelled, “Bao Cao,” indicating that I wanted to speak to the officer in charge.

After I had filled in the biography questions with false and misleading information, I was left lying on the floor in irons and handcuffs for another hour or so. It was probably the lowest point in my life. My fatigued and aching body bore little semblance to the strong, brave image I formerly had of myself. Though I had not cooperated or given anything of value, I felt miserably ashamed and totally defeated, like the weakest, most worthless officer ever to wear the uniform.

A short while later a guard brought food and water into the room and removed the cuffs and leg irons. After I had eaten, I was returned to my cell. Ken showed up an hour or so later. He had gone through a similar experience and also had filled out the forms with contrived answers. We consoled each other with the knowledge that we had done our best by forcing them to use torture to gain any compliance, while denying them what they wanted. In time we learned that virtually every POW in the camp had gone through this ordeal with the same outcome. Now our job was to bounce back for another round of resistance the next time the keys came rattling at our door.2

Although we all endured hardships, few suffered more than Naval Aviator Lieutenant Commander John McCain. A college wrestler and somewhat of a firebrand, he was probably the most severely wounded POW who lived to return home. During ejection and capture, his right arm was broken in three places; his left arm and right leg were broken; he sustained a football-size hematoma on one leg; and he suffered bayonet wounds and blows to the head. He probably would have died in captivity, but when the V read in the Stars and Stripes, the Pacific military newspaper, that he was the son of a four-star admiral, they kept him alive for potential propaganda value.

In 1968, “Cat”—that was our name for the communist political boss in charge of POWs—met with McCain and told him he would be released. The V had conducted an “early release” of three men earlier in the year as a ploy to convince the world of their “lenient and humane” treatment of POWs. Our internal guidelines stipulated that all POWs would return home in the order in which they were captured (first in, first out), except sick and wounded POWs were allowed to go first. Considering his lingering serious injuries, it was a difficult choice. McCain’s neighbor in the next cell whom he greatly respected, Captain Bob Craner (USAF), counseled him to go home. It was a tough decision. McCain says, “I wanted to say yes. I wanted to go home. I was tired and sick, and despite my bad attitude {toward the V}, I was afraid.”3 John could easily have justified his decision, accepted their offer, and returned home. Instead, he confronted his doubts and fears with his commitments to the honor of his family and the service of his country and fellow POWs. He would refuse early release.

In subsequent meetings, Cat continued to pressure McCain, even telling him that President Johnson had ordered him to come home.4 John called his bluff, making it clear that he would have nothing of it. He gave his final answer to the V in a voice loud enough for fellow POWs in nearby cells to overhear: He would stay until it was his time to go home. His actions sent a message that came through loud and clear as an example to everyone in the camps, “I will return with honor.”

McCain’s firm stance was rewarded with almost eighteen months of abuse—the longest period of maltreatment of anyone at the Plantation Camp.5 Whenever he was caught communicating, he was beaten by guards. Eventually they tied him in ropes, re-breaking his arm, until he finally agreed to sign a confession of wrongdoing with apology. Because he made the right and honorable choice, John did not gain relief from isolation and abuse until treatment improved for all of us in the fall of 1969. True to his word, McCain stayed to the end. He was captured eleven days before me, and we walked out together, flying home on the same aircraft.

My own working definition of courage is that it’s doing what is right or called for in the situation, even when it does not feel safe or natural. If your commitment (will) is strong enough, I believe you can muster the courage to make honorable choices in the face of virtually any challenge. The strength of your will is connected to your commitment to live from your deepest desires. Leading with honor is difficult; it can only be achieved when tied to such a commitment.

As you’ve probably concluded by now, acts of courage were common in the POW camps. In fact, it would take volumes to relate all of the stories I personally know. What about your experiences? Have you witnessed this type of courageous leadership in your organization? Do you know leaders who exhibit a similar commitment to doing what’s right? You probably know several, as do I. But unfortunately, when we’re honest, we have to admit that courageous leadership seems to be in short supply in many areas of our culture today.

Why is that? If these leaders in the POW camps could stand by their values in spite of humiliation, hardship, and torture, why do so many business professionals avoid making courageous choices in far less trying circumstances? If these POWs were willing to lean into the pain and take risks for their fellow prisoners, why are so few politicians willing to take risks in order to serve others? If these POWs were willing to fight so they could return with honor, why are so few leaders today willing to fight for what is honorable? Where is the courage in today’s society? Where is the honor? This entire book relates to these questions about courage and honor, because almost every chapter deals in some way with the need to confront our fears and do the right thing.

We often read or hear in the media about leaders whose lack of courage reaped painful consequences. But these “spectacular” failures are just the tip of the iceberg. Doubts and fears of a much smaller magnitude have caused legions of leaders to fail in less obvious ways. Although these failures don’t make the newspapers, they nevertheless can suck the energy and life out of the people and organizations they affect.

I believe that many of these less-obvious failures could be avoided if leaders learn (1) to affirm, (2) to confront, and (3) to listen. Let’s examine each of these in turn.

Tom, a division president in a Fortune 200 company, was a strong leader and a highly respected individual, but his reluctance to give positive feedback was hampering his leadership effectiveness. When I raised this issue, Tom said, “I don’t need affirmation myself, and I don’t feel comfortable giving it to others. I’ve tried praising people in the past, and it’s always felt awkward.” (As an aside, some executives I’ve worked with—Tom wasn’t one of them—“feel” strongly that feelings have no place in the work environment. Somehow, they fail to see the contradiction!)

Perhaps Tom’s discomfort was derived from a lack of affirmation in his childhood, the absence of positive role models early in his career, or his highly task-oriented, somewhat introverted temperament. Regardless of the cause, to his credit he acknowledged the problem and decided to lean into his fear. The next time Tom had an opportunity to compliment one of his staff, I helped him plan his approach. To ensure that his feedback was genuine and meaningful, we agreed that he would give very specific praise about an area where this VP had not only done well, but also knew she had done well.

The plan called for Tom to enter the VP’s office smiling, take a seat when invited, and engage her in a relaxed brief conversation about her newly adopted daughter and any other light topic that came up. Then he would stretch his smile and enthusiasm to the point of becoming uncomfortable and say, “Jane, I was very pleased with the way you handled the off site retreat last week. Your planning and coordination made it a very successful and fun event. Thank you for your hard work and innovation.” Then he was to excuse himself and head back to his office.

Tom’s exercise in courage lifted Jane’s spirits, energizing her to lead her team with more enthusiasm. It also gave Tom increased confidence in his ability to affirm his team. With this victory under his belt, he began to practice his newly acquired skill. The payoff was a boost in morale, energy, and teamwork that cascaded down through his leadership team deep into the organization. During the next two years of his incumbency, the organization thrived in spite of many challenges and substantial change.

Do you regularly affirm others? I’m not suggesting that you “flatter” them, but simply that you genuinely and consistently acknowledge their efforts and accomplishments, both large and small. Make affirmation a habit and watch what happens!

While many leaders shy away from giving praise, even more have difficulty offering constructive criticism and holding people accountable. Uncorrected problems are like cancers; once they start growing, they get worse.

Everywhere I go, leaders tell me about underperforming employees who are sucking the energy out of leaders and teams. Often the substandard performance has been dragging on for more than a year, and nothing has been done to “call the question.” Frequently I find myself having to coach leaders to initiate corrective action. It’s almost as if I have to build up their courage and give them permission to do what they know they should do.

Perhaps they’re afraid that if they speak frankly, people will dislike them. Or maybe they’re afraid that their forthrightness will heighten tensions or cause disruptions, so they avoid “rocking the boat.” Surprisingly, even the leaders who have a reputation for being “tough” often get very uncomfortable when negative emotions might be involved. Most people go to great lengths to avoid difficult conversations, controversial decisions, and unpopular actions.

Leaders who regularly avoid appropriate confrontation do a disservice to their followers, the organization, and themselves. Yes, directly engaging people and problems does entail risks, but avoiding troublesome issues creates even bigger risks. When poor performance and bad attitudes are allowed to fester, productivity will dramatically decline. When team members observe that management neglects obvious problems, they lose respect for their leadership and morale erodes.

As a workshop assignment, I once told a group of senior executives that they were each to have an honest conversation with one of their subordinates about a difficult issue that needed to be addressed. The following week, their reports to the class were enlightening. For example, one VP admitted that he had avoided dealing with a performance issue for some time. Challenged by the assignment and encouraged by the knowledge he had gained in the workshop, he confronted the employee in a strong but caring way. It turned out to be a powerful and positive conversation that cleared the air and moved the issue toward resolution.

I learned a lot about constructive confrontation from my three-time boss and long-time friend, Colonel Dick O’Grady, USAF. When I told him how much I respected the way he confronted issues rather than procrastinating, he said, “Lee, when you see a problem, you have to engage it. It usually doesn’t get better over time; it gets worse.” His example and counsel have helped my leadership enormously over the years. Hardly a week goes by that I don’t have an opportunity to share with a client this nugget of truth, one of the many “O’Gradyisms” that have helped me grow as a leader.

Tolerating bad situations is not fair to the organization, to the employees, to you as the leader, or to the offending individual. Festering problems are unhealthy and contagious, so why put up with them? Obviously, if it’s a personnel issue, consult first with Human Resources to make sure you do everything legally and in order. Then move in with a plan and take some action.6

It was said about General George Washington that he always “rode toward the sound of the gunfire.” Fearful leaders hang back; courageous leaders develop a game plan and engage the issues. Weak leaders procrastinate, sidestep, and avoid; strong leaders confront.

Many leaders make a third mistake: they fail to listen to the ideas, opinions, and constructive feedback of others. Some go so far as to use intimidation to silence “threatening” ideas. Still others suppress ideas by dominating conversations and not allowing others to speak. These leaders may appear “macho” on the outside, but in reality their fears and insecurities send a loud message that they don’t want anyone to disagree with their view of the world. Unfortunately, most of us know how exhausting and demoralizing it can be to work for a leader whose tender ego must be carefully guarded. Usually there is a graveyard outside this executive’s office that’s filled with the bodies of messengers who had the courage to provide honest feedback.

If you suspect that you are this type of person, let me encourage you to get a “leadership 360 assessment,” so your direct reports, peers, and manager (or board of directors) can give you candid, anonymous feedback. (Now, that will take some real courage on everyone’s part, won’t it!) If the results indicate a problem, don’t rationalize your behaviors or demonize the messengers. Engage the issues and grow into the leader you can be, the one that your followers deserve.

When the truth is courageously communicated, people and organizations flourish. But when doubts and fears hold sway, leaders avoid hard decisions and responsible actions, and instead look for a comfortable way out. At best, team energy drains away and people don’t grow. Too often, fear and doubt cause bad judgment that derails the leader’s influence.

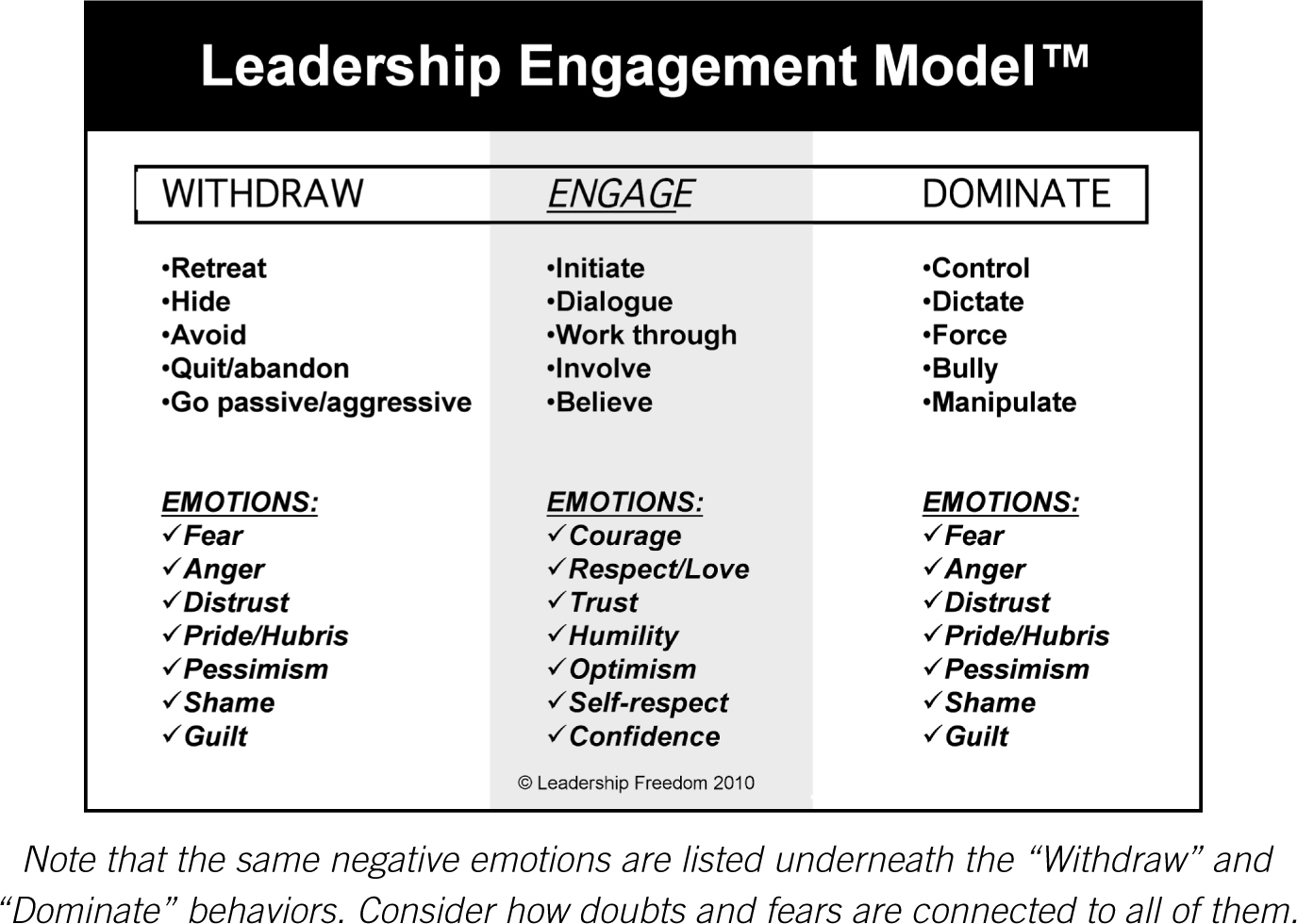

Leaders who lack courage to engage problems usually veer off course in one of two directions: they will either seek to dominate, or they will seek to withdraw (fight or flight; violence or silence.)7 Both of these counterproductive behaviors have the same root cause: fears and doubts.

I’ve found the Leadership Engagement Model™ depicted below to be extremely helpful for improving the cooperation and productivity of teams working cross-functionally, especially if a “silo mentality” is prevalent. It has also been beneficial for strategic partners who have competing interests.

For example, in most medical communities a natural tension exists between the hospital and the physicians and clinics that use the hospital. Typically, one party tries to dominate to get its way, which in turn causes the other party to become distrustful and combative. Eventually, emotions can get so raw that one party withdraws, or they both do. To halt this vicious cycle, the two sides need to courageously commit to engage in productive dialog, identify common goals, and implement agreed-upon solutions. Meaningful engagement occurs when each party fights for its ideas in a healthy, constructive way, while still being open to the ideas of others. This type of dialog is evidence of humility, courage, and confidence.

Doubts and fears are normal. You can’t avoid them, but you can manage them. You can choose to override your feelings and do the right thing. You can choose to lean into the pain for the good of others and yourself. Like the men in the POW camps you’ve read about, you can choose to be a strong leader by being courageous.

Foot Stomper: Authentic leaders develop courage as an act of will. Choose today to do what you know to be right, even when it feels unnatural or unsafe. Trust yourself, honor your values, lean into your pain, and intentionally engage issues with strength and humility, despite your fears.

Foot Stomper: Authentic leaders develop courage as an act of will. Choose today to do what you know to be right, even when it feels unnatural or unsafe. Trust yourself, honor your values, lean into your pain, and intentionally engage issues with strength and humility, despite your fears.

Coaching: CONFRONT YOUR DOUBTS AND FEARS

Coaching: CONFRONT YOUR DOUBTS AND FEARS

As in every area of leadership development, step one is awareness. The questions below may help you identify ways in which you can develop more courage.

1. What type(s) of courage might you be lacking: physical courage, professional or political courage, reputational courage, financial courage, personal and emotional courage, relational courage?

For example, with respect to relational courage, does fear keep you from holding others accountable at work? Do you shy away from setting boundaries with others? Do you lack the personal and emotional courage to give and receive constructive feedback?

2. In what specific situations might you be dominating or withdrawing (e.g., by attacking or procrastinating) when you should be engaging?

3. What choices do you need to make to engage issues you have been avoiding?

Note: To download an expanded version of these coaching questions for writing your responses, visit LeadingWithHonor.com.

1 John M. McGrath, Prisoner of War: Six Years in Hanoi. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1975) 45.

2 Hearing the turnkey’s key rattle outside the cell other than at normal mealtimes or bucket-emptying times set off an emotional alarm that something bad was about to happen.

3 John S. McCain and Mark Salter, Faith of My Fathers. (New York, NY: Random House, 1999) 235.

4 John Hubbell, POW: A Definitive History of the American Prisoner-of-War Experience in Vietnam, 1964-1973. (New York, NY: The Readers Digest Press, 1976) 452.

5 Zalin Grant, “John McCain, How the POWs Fought Back,” US News & World Report, May 14, 1973, 49-51.

6 See these books for help on holding others accountable: Crucial Confrontations by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler. Conversations by Susan Scott.

7 The book Crucial Conversations (Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler) gives many tips on how to engage effectively and uses the terms “silence” and “violence” to describe withdrawing and dominating behaviors.