“Winning isn’t everything, but the will to win is everything.”

Vince Lombardi

By the time Operation Rolling Thunder air campaign over North Vietnam began in the spring of 1965, Hanoi and Haiphong were the most highly defended areas in the world. More than 70 percent of American POWs during the war were pilots and crew members shot down in that campaign. Air Force Lt Col Robbie Risner and Navy Commanders Jeremiah Denton and Jim Stockdale were among the first casualties. These squadron commanders already had been recognized as exceptional leaders prior to their capture. As survivors of the Great Depression and World War II, they were among the youngest members of what Tom Brokaw called “The Greatest Generation.” Bright, well-educated, courageous, strong-willed, and as tough as nails, these three were men of honor to whom we all looked for guidance and inspiration.

The North Vietnamese constantly sought to use senior POWs as propaganda tools in staged press conferences. Korean War Ace1 Robbie Risner, our camp SRO during the early days, was a prime target for exploitation. Prior to parading Risner before a “peace delegation,” the V tortured him and prepped him on how to answer reporters’ questions. Risner infuriated his captors during the press conference by refusing to regurgitate the party line. Aware that they had promised to give a journalist access to two family photographs he had received from home, he tore up the photos, hid them in the waste bucket, and refused to disclose their location. Because the V badly wanted the photos for propaganda purposes and did not want to lose face with the journalist, they frantically searched his cell for them, but to no avail. The one place they didn’t look was at the bottom of that pail of human excrement.

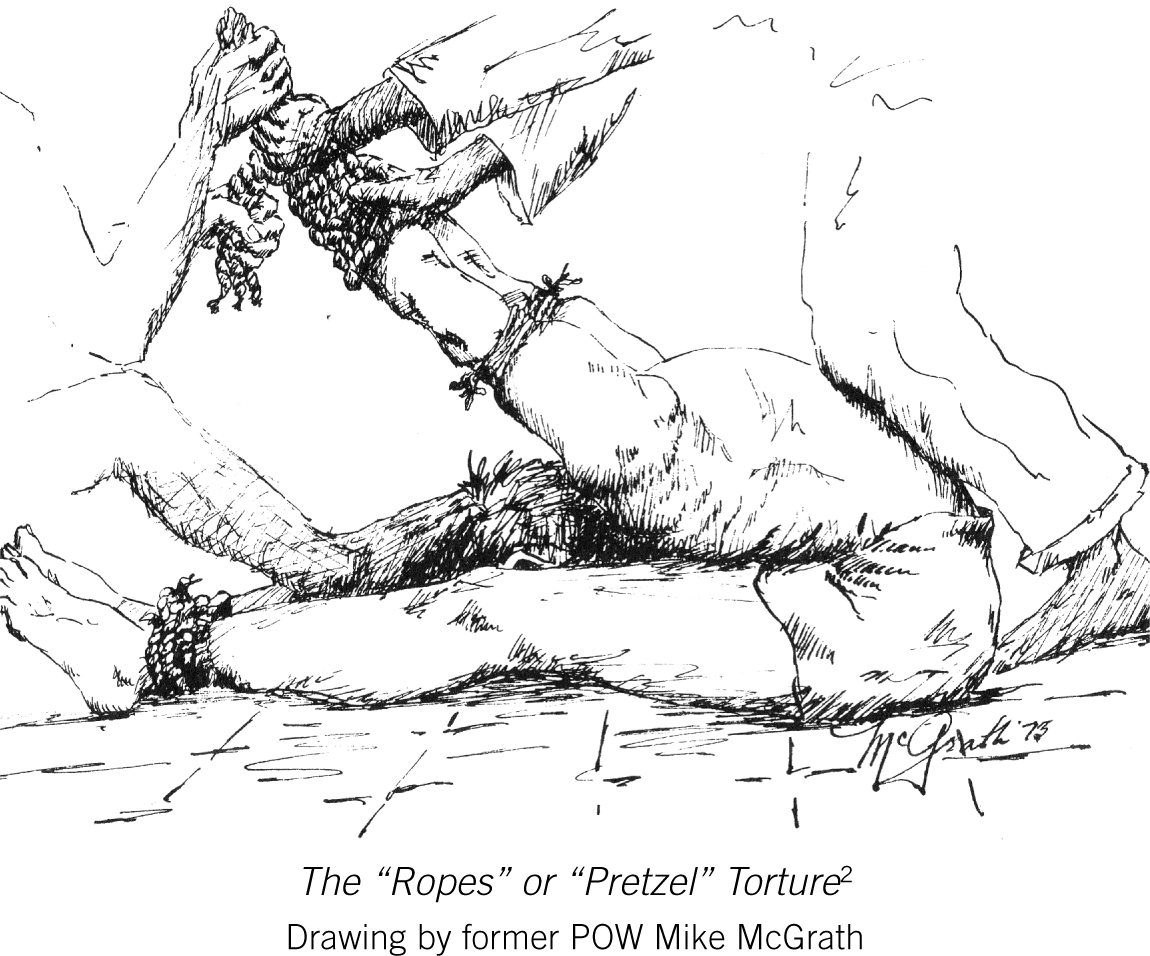

In an effort to force him to produce the photos, the guards severely beat Robbie and put him through the rope torture. The “ropes,” or “pretzel” as it was sometimes called, was a terrifying and brutal method for breaking POWs. After the prisoner’s legs were tied together, his arms were laced tightly behind his back until the elbows touched and the shoulders were virtually pulled out of joint. Then the torturer would push the bound arms up and over the head, while applying pressure with a knee to the victim’s back, as shown in the graphic below.

During torture, the circulation is cut off and the limbs go to sleep, but the joint pain continues to increase as the ligaments and muscles tear. When the ropes are finally removed, circulation surges back into the “dead” limbs, causing excruciating pain.

When the V eventually learned what Risner had done with the photos, they furiously inflicted more torture until Robbie agreed to sign a confession and an apology for committing “grave crimes.” Under such severe torture, no POW could resist signing these forced statements. We took some comfort in the fact that they invariably sounded phony, because they were dictated by the V using awkward sentence structure and expressions that no American would use. Sometimes they were so ridiculous they made the V look foolish.

After torture, the guards boarded up the window in Risner’s cell, making it so dark he couldn’t see the walls. Robbie had never been afraid of the dark, but he immediately began to have panic attacks. In later describing this episode he said, “It was as if I had an animal on my back. Absolute panic had set in. The fact that I could not control this thing driving me caused me to be even more panic-stricken … sheer desolation permeated the miserable dark cell I lived in twenty-four hours a day.”3

Risner’s only relief was to keep moving and praying. He would walk around his cell—often covering as many as twenty miles a day—and do pushups and sit-ups, until he was exhausted enough to fall asleep. If he awakened during the night, he had to resume exercising until he was again exhausted enough to sleep. It was a maddening existence. At times he wanted to scream, but since that would bring more torture, he would hide under his mosquito net, stuff something in his mouth, wrap his blanket around his head, and “just holler” until the anxiety eased. Often he had to talk himself into making it through one more minute and then one more minute. As he put it, “I literally lived one minute at a time.”4

After ten months of darkness, the night finally passed. In June 1968, the V moved Robbie into the Golden Nugget section of Little Vegas. From our cell about forty feet away, we heard him moaning and screaming in nightmares throughout that first night. The next day, when Robbie’s shutters were opened, I saw his tired but smiling face for the first time. During siesta, while the guards were generally less alert, Risner and I made contact. Over the next few days, he shared his story and basic guidance by writing with his index finger on his open palm, one letter of the alphabet at a time. It was clear that he had a lot of fight left in him. His courage served as inspiration for the rest of us in the months and years ahead.

Facing similar propaganda exploitation, CDR Jeremiah Denton endured excruciating torture before finally agreeing to go before the propaganda cameras. Prior to filming, his captors prepped him for several days on what he was supposed to say about America’s “cruel and oppressive war.” But in the press conference, Denton, at risk of his life, departed from the party-line script and said, “… whatever my government is doing, I agree with it, and I will support it as long as I live.”

The V were stunned. Not wanting to lose face with the reporters, however, they allowed Denton to continue answering questions about the daily camp routine. They were unaware that as the cameras rolled, he was blinking his eyes in Morse code: T – O – R – T – U – R – E.5 The payoff was huge. When the video of the interview went public, it was the first time the U.S. government had accurate information about the treatment of POWs.

Angered by Denton’s departure from the script, but still unaware of his encoded communication, the V displayed their trophy at another staged press conference two weeks later. This time Denton stood up while on camera and walked out. The consequences were severe. The V put Denton in the rope torture and then beat him until he was unconscious.6

Denton’s courage is all the more exemplary when one considers that he knew that this type of torture awaited him if he defied his captors.7 During more than seven years in captivity, he never hesitated to provide leadership when he was the SRO of a cellblock or camp. Although that made him a prime target for abuse and exploitation by the enemy, he steadfastly pushed himself and the enemy to the limit. He deliberately kept the torture team occupied, so they would have less time to harass his fellow POWs. Denton’s will to win was motivated by his strong sense of personal and professional commitment, undergirded by his deep faith in God.

By the time Navy CDR James Bond Stockdale was shot down and captured, two months after Denton, he had already established a reputation as an outstanding aviator, with more than two hundred combat missions to his credit. A year earlier, he had been the first man on the scene at the Gulf of Tonkin incident, the still-controversial event that landed Navy LT Everett (Ev) Alvarez in Hanoi, where he led a lonely six-month existence until other American POWs began to arrive.8

Stockdale was a twentieth-century Renaissance man. As a teenager, he played piano, acted in leading roles in his high school drama club, and was a stalwart on the football team. After graduating from the U. S. Naval Academy, he became one of the Navy’s top test pilots. Later the Navy sent him to postgraduate school to earn a master’s degree in international relations at Stanford University, where he became a dedicated student of the classics. The faculty encouraged him to pursue a doctorate degree, but he decided to return to his first love as a fighter pilot. Stockdale’s keen understanding of Marxism and his appreciation for the classics, especially Stoicism, equipped him well for his role as a POW leader.

When his plane was shot down over North Vietnam, Stockdale sustained a broken back during ejection. Following his capture, the civilian populace severely beat him, breaking his leg and dislocating his shoulder. A medic was about to amputate his leg, but Stockdale returned to consciousness just in time to convince him to apply a cast. In spite of his injuries, the V tortured him in the months ahead, even kicking and yanking his dangling limbs to increase the pain.

CDR Stockdale, as SRO in Little Vegas, helped instill a strong and unified culture in the camps that raised morale and increased POW resistance. The V began a purge, torturing men viciously to find out who was responsible.9 Stockdale was eventually exposed and moved to the torture chambers, where he underwent severe beatings, torture cuffs,10 and the ropes, until he finally agreed to sign a “confession.”

Because Stockdale was such a determined resistor and the senior ranking naval officer in the camps, the enemy constantly targeted him for exploitation. In early 1968, after considerable torture, they arranged for him to perform as an actor in a propaganda film. Recognizing what they were up to, Stockdale used the razor they had given him for shaving his beard to cut his hair into a reverse Mohawk. In the process, he deliberately sliced his scalp so that it bled profusely. Not to be denied, the V brought their “actor” a hat to wear for the filming. Left alone in the interrogation room, Stockdale grabbed a wooden stool and beat his face until it was a bloody pulp, rendering himself unusable for the filming.11

CDR Stockdale went through torture periodically for the next three years. During his seven and a half years of captivity, he spent more than four years in solitary confinement, two of which were in the infamous “Alcatraz Prison,” yet he maintained his fighting spirit. The severe injuries Stockdale suffered during ejection from his aircraft and subsequent capture were never adequately treated; he walked with a severe limp for the rest of his life. Ever the Stoic, however, he was mentally well prepared for his disability and often encouraged himself with the words of his favorite Stoic, Epictetus: “Lameness is an impediment to the leg but not to the will.” Like Risner, Denton, and many other exemplary leaders in the POW camps, Stockdale understood that a person who won’t quit can’t be beaten.

Life itself is a fight at virtually every turn. To win in sports, the athlete must fight against the limitations of the body and the efforts of the competition. To win the new job, the candidate must fight for the interview and for the offer. To win at home, the spouse or parent must fight against the natural human traits of selfishness and pride. Even to win at a simple game of chess or bridge or golf, the player must fight with tenacious concentration.

Nothing worthwhile in life comes easily. Some days you will feel good, and some days you won’t. But regardless of feelings and circumstances, you must make up your mind to persevere. If you want to be victorious, you must decide in advance to fight to win. That’s what the senior leaders did. They went first, and they set the bar very high.

The battles in your organization are probably less intense than those that took place in the POW camps, but they can be daunting nevertheless. If you’re a business leader, for example, you must constantly fight to increase revenues, develop new products, attract new employees, complete projects on time, promote teamwork, ensure quality, confront employees who are underperforming, and achieve a host of other important goals. In fact, you must in a very real sense fight for the survival of your organization every day. What’s more, you must continually fight to uphold your personal and professional commitments and values, in spite of fears, doubts, and temptations to compromise. That requires the same kind of tenacity POW leaders exhibited.

As a kid, we used to play pickup games of basketball and touch football. The two best players would take turns choosing the players they wanted on their team. The smart leaders didn’t always select the players with the most natural talent. They picked the ones who had the greatest desire to win, who had what we call “fire in their belly.” So it is with life. Talent, education, charisma, and good looks will only get you so far. To win in life, you must want to win and you must fight to win.

In the business context, highly motivated people are said to have “drive,” or perhaps a “pioneering spirit.” They are willing and even eager to step out into uncharted territories, launch new initiatives, take on the most challenging tasks, and pursue lofty goals. Leaders with drive inspire, push, persuade, direct, and challenge others to take the actions that are required to attain the goals that are desired.

Leaders who are driven to win in every undertaking typically manifest the positive personality traits of assertiveness, initiative, desire for achievement, persistence, and ambition. These are good qualities. Leaders with strong drive get things done. But as in other areas of life, too much of a good thing can be counterproductive. When all of these traits are in play without an awareness and concern for the capabilities and needs of others, watch out! A “driven” leader who is inordinately focused on results can push others into “burnout” rather quickly. That’s not healthy for the organization or for the individuals involved.

Other personality styles focus their drive on a more limited set of goals. For example, some athletes are extremely competitive when engaging in their sport, but are not so driven in other areas. I witnessed this a few years ago while providing career coaching to professional athletes who were approaching retirement. One All-Pro NFL football player was a fierce competitor on the field, but he was relaxed and somewhat laid back when engaged in other activities. His drive to win centered on his passion for the game. It was fueled by his desire to be the best in his field.

On another consulting assignment where I was asked to assess the personality traits of various store managers, I encountered one leader who measured quite low in the area of drive. She was very successful on the job, however, so we dug deeper. It turned out that her drive came from a strong motivation in two seemingly unrelated areas: to provide great customer service and to creatively present innovative products and services.

In some individuals this pioneering drive is a dominant personality trait that affects broad areas of their lives; these people will fight to win at every undertaking. Others who might be world-class performers in their profession might have that same kind of fight in only a few endeavors; it’s just the way they are wired. Good leaders have a knack for identifying the sources of each individual’s unique drive to win, and then tapping into it for the benefit of the organization and the individual.

Fighter pilots by nature are competitive. They have to be, because they’re trained to engage in life-and-death combat. But in most work environments, ultra-high competitiveness is counterproductive. “Fighting” needs to fit the environment and the situation. In all organizations, striving to win at the expense of others is a losing proposition. An insatiable need to always be right and win every argument can derail relationships and even careers.

On several occasions I’ve been asked to coach executives who were outstanding in almost every way, except they had excessive drive. Some were so dominant they could not cooperate with their teammates, and at times they even bucked their boss. They made a habit of turning discussions about minor issues into arguments. These individuals were good people with good intentions, but they could not see that their behaviors were out of balance. My job was to help them become aware in the moment of the situational dynamics, so they could then learn to manage their interactions in a successful way.

I’ll never forget one individual who called to tell me about his success. He said that after a staff meeting one of his peers came to him and asked him if he was feeling okay. He replied, “Sure, why do you ask?” His peer responded, “You were not yourself today in the meeting. You were quieter than usual and didn’t get into any arguments.” My client was quite proud of his achievements, and so was I. He didn’t reinvent himself, but he did learn to manage his natural drive to win. His career has continued upward, and he now manages a large segment of a Fortune 100 company.

Drive is a helpful quality, but like most other leadership traits, it can be powered by inappropriate motivations. When individuals allow unbridled ambition, greed, or other unhealthy needs to fuel their desire to win, the results are almost invariably destructive for that person and for the organization. Legitimate needs and worthwhile goals are seldom met when “steamroller” methods are used to pursue selfish desires.

When fighting to win, know when to fight. Sometimes you have to withdraw from the battle for a while. As POWs, there came a time during torture when it was evident we could not beat them at their game. We had to find a different approach for achieving our goals. When you know for sure you can’t win, it’s probably time to quit doing what you’re doing and rethink your strategy. But before throwing in the towel, check with your teammates, your mentor, or others you trust to get their counsel. And, keep in mind the “First Law of Holes: When you’re in one, stop digging!”12

Outstanding leaders seek to understand the true nature of their own motivations and the motivations of those they lead, and then they make adjustments as necessary. As Jim Collins points out in his best selling book Good to Great, the best leaders are typically highly competitive, but they harness that competitiveness for the good of the organization, not to boost their own egos.

Drive (energy to overcome obstacles) can come from a variety of sources. Having a clear understanding of your deepest motivations provides significant self-awareness and enables you to manage and coach yourself. Reflect on these questions to gain more insights about the sources and effects of your drive.

1. What are the primary sources of your drive?

(Check all that strongly apply.)

| • | Desire to achieve goals | • Desire for power |

| • | Desire to excel | • Passion for what I’m doing |

| • | Desire to do my best | • Challenge of competing |

| • | Desire to be number one | • Fear of failure |

| • | Desire to serve others | • Thrill of success |

| • | Desire to honor God | • Love of the “game” |

| • | Desire for money | • Love of adventure |

| • | Desire for recognition | • Drive to look good |

| • | Desire to please others | • Other sources of drive … |

2. Are your drive and ambition focused on helping the team succeed?

If your drive is too intense or too weak, in what ways might you be hurting the team? How could you find out how you are affecting others? Will you make an effort to find out?

3. Does your drive to win interfere with your relationships? Do you tend to “beat people down” or “lift them up”? How can you learn about how you influence the motivations and confidence of others?

Note: To download an expanded version of these coaching questions for writing your responses, visit LeadingWithHonor.com.

1 Lt Col Risner had been the squadron commander for five of the early POWs, including Majors Larry Guarino, Ron Byrne, and Ray Merritt, and Captains Smitty Harris and Wes Schierman.

2 John M. McGrath, Prisoner of War: Six Years in Hanoi. (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1975) 79.

3 Robinson Risner, The Passing of the Night. (Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 1973) 178-179.

4 Risner, 180.

5 A video of the press conference showing Denton blinking T-O-R-T-U-R-E is available at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BgelmcOdS38 (accessed May 15, 2010).

6 Denton was awarded the Navy Cross for courage and gallantry as a POW. This medal is the highest award given by the Navy.

7 Denton documented his POW experience not long after our release in a book appropriately titled When Hell Was in Session. In 1979, the book was made into a movie with actor Hal Holbrook playing Denton. Eva Marie Saint played his courageous wife Jane, who soldiered on at home, rearing seven children while her husband was a POW for seven and a half years.

8 American warships patrolling the Gulf of Tonkin reported radar contact with what was believed to be enemy gunboats. President Johnson used this event to launch attacks on North Vietnamese targets.

9 This was the same purge (Stockdale Purge) that made it so difficult for us to communicate when we arrived in Little Vegas in the fall of 1967. The purge was so effective that we did not know much of the camp history until the long-term POWs moved in next door at Son Tay in November 1968.

10 Torture cuffs were handcuffs that could be ratcheted down tighter and tighter until they cut off circulation, even cut through the skin into the muscle. On some men, they cut deep enough to expose bone.

11 Stockdale was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroism in the North Vietnamese prisons.

12 Denis Healey, “Brainy Quotes,” http://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/authors/d/denis_healey.html (accessed November 14, 2010).