“Any organization develops people: it has no choice. It either helps them grow or stunts them.”

Peter Drucker

Military professionals by nature are action-oriented high achievers who want to make the most of every opportunity. Even though our futures were uncertain and our resources were sparse, we looked for activities that would give us some measure of growth and accomplishment. We were motivated simply by the desire to sharpen our minds and develop knowledge and skills that someday might be helpful.

When the mind is free from clutter, it’s amazing how memory and cognitive effectiveness improve.1 After our release, the intelligence officers who debriefed us were astonished at the level of detail we could recall. Most of us could remember the exact dates—even the days of the week—of every significant event in our lives as POWs.

As we moved around from camp to camp and engaged in covert communications, most of us collected the names of the POWs in the Hanoi system. At one point, I had memorized in alphabetical order more than a hundred and fifty names. But cellmate Navy LCDR JB McKamey won the prize. Almost daily he paced around the cell reciting the names of nearly three hundred POWs.

Before my deployment to Southeast Asia, Air Force 1st Lt Lance Sijan and I had been dormmates and golfing buddies. At Son Tay camp, I learned that his plane had gone down one day after mine. Badly injured, he survived in the jungles of Laos for forty-six days before being captured. His remarkable story was not a surprise. Throughout our training he was always keen about his professional development. Lance stood out in survival school because he appeared to be the most highly motivated learner, both in the classroom and on the mountain trek.

As Ron Mastin (1st Lt, USAF) flashed Lance’s painful story across the camp to our building, I put the pieces together. I remembered our first winter of captivity, when my cellmates and I had listened helplessly as someone in a cell down the hall deliriously cried out for help. I summoned the officer in charge, and a few minutes later Fat in the Fire opened the peephole in our door. “Please, will you help this man?” I pleaded. With a serious look on his face he replied, “He has bad head injury. Been in jungle too long. Has one foot in grave.” He slammed the peephole shut and left.

Of course, in the isolated cells of Thunderbird, we had no way of knowing who was dying. Two years later, I realized that we had been audible witnesses to Lance’s last valiant struggle to survive.2 After the war, we learned more details of Lance’s heroic actions to evade, escape, and endure. His courageous efforts to resist, survive, escape, and return with honor were so notable that he was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor (posthumously). One of the Air Force’s most prestigious annual awards for leadership is named the Sijan Award.

We POWs spent many hours remembering incidents and people from our past. When I couldn’t recall someone’s name, I would concentrate until it came to me. Sometimes it would take a couple of weeks, but eventually the name would pop into my mind or come to me in a dream. Once I spent several days recalling the names of everybody in my eighth grade class. I could remember where they sat, what the classroom looked like, and what we studied.

When I came home, people in my home town of Commerce, Georgia, were amazed at how well I remembered their names. Of course, I had met very few new people over those five-plus years as a POW, and I had kept old acquaintances and friends alive in my mind through daily reflections and mental exercise.

During my second year of incarceration, I began to put my imagination to work on specific projects. For example, I mentally operated a forty-acre farm. I designed and built the fences; purchased livestock and the farm equipment; calculated the costs for planting, fertilizing, cultivating, and harvesting the crops; set the selling prices; and calculated the profits. Naturally, I exempted myself from taxes.

I would spend as many as ten hours a day on this project, sometimes working my brain so hard that I got an intense headache. At the end of four weeks—which I had mentally expanded into several growing seasons—I owned most of the land in the county, as well as my own feed mills and a railroad siding for shipping. Running an imaginary farm business sharpened my math and reasoning skills and made it easier for me to catch up with my peers academically when I returned home. The experience also proved useful when I bought and operated a sixty-four-acre Texas grain sorghum farm near San Antonio five years after my release.

The next project was stimulated by my interest in becoming an attorney. I spent several weeks deciding what kind of lawyer I would be and where I would go to school. After quite a lot of research using our covert communication system, I decided that I would attend the University of Virginia law school and become a tax attorney. Most of the POWs engaged in similar “Walter Mitty” fantasies, which sound somewhat bizarre now, but in that environment helped preserve our sanity.

Although I’ve never had much time for golf, I enjoy the game. So I exercised my mind during my 1,955 days of captivity by remembering most of the courses I had played. Sometimes it would take me several days, but I could eventually remember all eighteen holes on a golf course I had played only three or four times. I would replay each hole, remembering where the sand traps and other features were and what shots I had actually made. I also could remember many of the shots my former golfing buddy Lance Sijan had made. In my memory, as in real life, he drove the ball much farther than I.

One day the turnkey inadvertently left the shutters open on a nearby cell, and I saw a fellow POW (future cellmate Air Force Captain Bob Peel) practicing his typing on an imaginary typewriter. That seemed like a brilliant idea, so I started doing the same. When I returned home, I could type faster and more accurately than ever. What a blessing that turned out to be in this age of computers.

Our captors surprised us with a rudimentary chess set one day, which they had allowed the POWs in another cell to make. The board was made from cardboard, and the pieces were flat strips of brown toilet paper layered and glued together, with the first letter of each piece neatly labeled. Ken, Jim, and I spent so much time playing that we learned to see the chessboard in our minds. At bedtime, we would lie on the hard boards that were our bunks and mentally review every move of that day’s game.

By temperament I am an action person, and in my pre-Vietnam days I didn’t generally like to take time for board games and complex thinking. But playing chess and bridge developed my ability to focus deeply and think logically. By the time I returned home, my mind had a remarkable facility for memorization, visualization, and conceptualization, and I could do rather complex math problems in my head. Although this mental agility has diminished with time due to the “noise” and information overload of modern life, a fair amount is still with me and has proved to be extremely beneficial. Without it, I doubt that I could have written this book.

Even though Camp Unity had much larger rooms—my cell measured about twenty-five feet by seventy feet—fifty-five of us were jammed in there like sardines, twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Fortunately there was adequate space to walk.

We never knew if or when there might be another rescue attempt, and Lt Col Risner, now our camp director of operations, wanted to make sure we were physically able to walk out of captivity if the opportunity arose. He asked all room SROs to test each man’s fitness and send back a report. Our room SRO, Lieutenant Commander Doug Clower, suspended all other activities for a day and took us on a ten-mile hike around the perimeter of our cell. If the guards peeked in, they probably wondered why fifty-five men were pacing all day around this small room. The hardest part for me was just keeping up with my long-legged friend and mentor Capt Jay Jayroe. This different activity was fun, and it boosted our morale when everyone made it.

In such close quarters, SRO Clower quickly realized that things could get dicey if we didn’t have activities to occupy our time. So he asked Captain Tom Storey (USAF), an experienced educator, to launch a learning program. Tom listed various study options using the concrete slab floor as his blackboard and pieces of broken brick as chalk. The electives included math, calculus, science, history, Spanish, German, French, electronics, German wines, and public speaking.

That evening around sundown, we had our regular room meeting to make announcements, celebrate birthdays, acknowledge shoot-down anniversaries, and engage in a brief period of silence, which was our transition from the daytime to the evening schedule. With fifty-five of us constantly chatting and moving, it was our only time all day for quiet reflection and meditation. During announcements, Tom shared his plans and invited us to use the “chalk” to mark our course preferences. Based on this survey, he organized the subjects and recruited the most qualified instructors.

One track of courses was taught on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, and another on Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday. School was in session three hours in the mornings and two hours in the afternoons.

On selected nights during the week we would have special interest programs, when someone might talk about a book he had read, a movie he had seen, or a trip he had taken. A Toastmasters public speaking group met at one end of the room two nights a week. On Sunday mornings we had a church service, complete with a choir of eight guys who actually could sing.

I taught basic French and studied basic Spanish and German, as well as intermediate French. For about a year, two other guys and I practiced these three languages fifteen minutes a day, six days a week. My goal was to become fluent in French and Spanish and have a two-thousand-word working vocabulary in German. The good news is that I achieved my goals. The bad news is that I was a POW long enough to accomplish these goals and many others.

We had no books, so all subjects were taught from memory. It’s remarkable how much talent resided in that group of military men. For example, Navy LT Denver Key, with whom I shared a cell for almost four years, taught a small group of us differential calculus. We wrote our problems on the concrete-slab floor using pieces of brick as chalk. Denver loved math and had a gift for teaching, so the class was fun and we learned a lot.

In the camps we had alumni from elite schools like MIT, Stanford, Notre Dame, Georgia Tech, Purdue, Duke, and all three service academies. But in fields other than math and engineering, Jim Warner was like a one-man university; he had an unquenchable curiosity, a photographic mind, and a remarkable memory. He was literally a “walking encyclopedia.”

In fact, that’s where it all started. When Warner was six or seven, his parents bought an encyclopedia set from a door-to-door salesman. Jim read it from A-Z and still remembered much of it. He loved literature, history, politics, and science, and could recall the most notable ideas of every major philosopher in Western culture. He spoke French, Spanish, and some German, and he could read Latin. Fortunately for our self-esteem, there were a few things he didn’t know. For instance, he wasn’t aware that one could buy a car for less than the sticker price.

Memorizing poetry was a popular project throughout the camps. People who had memorized various works contributed them to our “library,” so they could be used by others. Typical poems that most of us memorized included “The Highwayman” by Alfred Noyse, “Ballad of East and West” and “If” by Rudyard Kipling, “The Cremation of Sam McGee” by Robert Service, and “The Gift Outright,” which Robert Frost delivered at President Kennedy’s inauguration. Many of the men also memorized scripture, especially Psalms 1, 23, and 100.

Most cells had similar ongoing educational programs, and someone came up with the idea of organizing an officer candidate school for the only three Air Force enlisted men in the Hanoi POW camps. A number of officers developed a rigorous curriculum and volunteered to teach the various components of the course. When the three men returned home, the U. S. Congress approved the program and offered the candidates commissions as second lieutenants in the U.S. Air Force. One was close to retirement, so he declined. The other two men accepted their commissions and enjoyed successful careers.

The lack of books or outside resources did not limit our continuous learning in the POW camps. We relied on recall of past education, and where there was a lack of clarity on a subject, we tried to get a consensus of the best minds. Eventually many areas were codified into what we called “Hanoi Fact”— meaning it was accepted as true until we were released and could verify the information. The in-house joke was that some men whose education had been slighted before capture and now proudly posed as experts, had been totally educated by Hanoi Fact. Fortunately, it turned out that our facts were amazingly accurate. Our investment in development has paid big dividends in the years since.

American military training is unsurpassed. It has to be, because combat is literally a matter of life and death. Training in the armed services is an ongoing process, not simply a series of one-time events. For example, ground egress and ejection seat training were required every six months in peacetime, and at least monthly when we were in combat. I was certainly thankful for that when I had to eject over enemy territory. In fact, I’m amazed and very grateful for how the on-going preparation I received enabled me so many times in my career to make decisions and take actions calmly and efficiently in the midst of crises.

In civilian life, as in the military, preparation and continuous learning supported by consistent reinforcement are crucial for sustained success. Not surprisingly, research shows that the companies who invest in high-quality, on-going training are more profitable than those who don’t.3 Building “muscle memory” and confidence is vital for reliable execution, especially under pressure. Training-and-development pros know that isolated training events seldom develop genuine competence.

On January 15, 2009, shortly after takeoff from New York’s LaGuardia Airport, US Airways Flight 1549 collided with a flock of birds, causing both engines to flame out. With absolutely no power, Captain Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger’s only option was to attempt one of the most difficult feats in aviation: a crash landing on water. He knew if he didn’t contact the Hudson River at precisely the right angle, his plane would either break apart or plunge beneath the water’s surface. One or two degrees difference in the glide path could mean the difference between life and death for all 155 passengers and crew on board.

Fortunately, there could not have been a better-prepared person flying that aircraft. Sully’s entire life since earning a pilot’s license at age sixteen had been focused on aviation. At the Air Force Academy, he had graduated as “top flier” and winner of the Outstanding Aviation Award, and he subsequently had distinguished himself as a top fighter pilot in the Air Force.

When Sully left military service to become a commercial pilot, he maintained his commitment to continuous learning and improvement. He was so knowledgeable, in fact, that he was often called as an expert witness during aviation inquiries. On that fateful day over New York City, Captain Sullenberger drew on forty years of aviation experience that included 27,000 hours of flight time, hundreds of hours of flight simulator training, years of regular classroom instruction, and an extensive background of technical research into flying safety.

Anyone who has seen the video of Sully’s landing can’t help but marvel at his precise execution. Many military and commercial pilots have lost an engine to birds somewhere along the way, but few have ever lost all their engines and lived to tell about it. It’s even more astounding that Sully and his crew accomplished this feat in a large commercial airliner over a major city without a single loss of life. This “miracle on the Hudson,” which earned Sully the number two spot on Time magazine’s list of the Top 100 Most Influential Heroes and Icons of 2009, resoundingly testifies to the value of thorough preparation and continuous learning.

In his best-selling book, The Talent Code: Greatness Isn’t Born. It’s Grown. Here’s How., Daniel Coyle says that it takes about ten thousand hours of “deep practice” for professionals to become tops in their field. The author points out that top athletes, great musicians, and other performers all have coaches, and they practice much more than they perform. For example, the top professional golfers typically hit three hundred to four hundred balls a day.

Likewise, outstanding organizational leaders are always learning and growing. They practice their skills, benefit from coaching, gain awareness of their performance through regular critiques, and hone their abilities through continuous development. On the other hand, less successful leaders typically spend so much time “performing” that they have no time for “practice,” and the thought of having a professional coach is foreign to them.

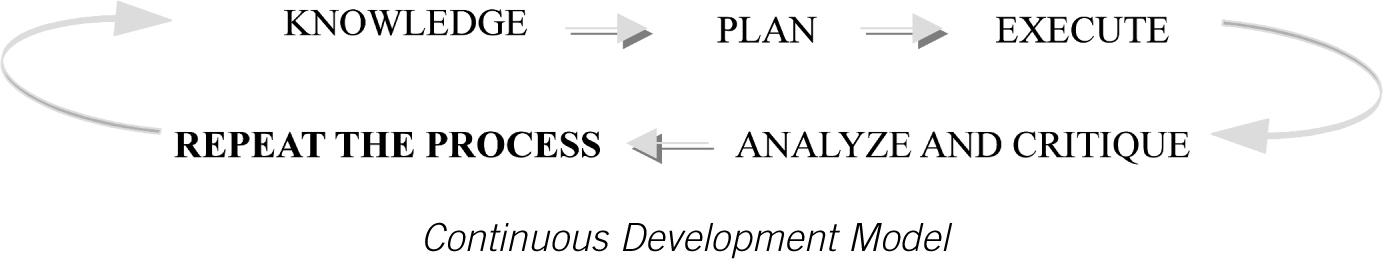

The diagram below depicts the development method used by virtually all highly successful individuals and organizations. When I employ this process with my executive coaching clients, they’re able to achieve increasingly higher levels of performance with each cycle.

A few years ago I collaborated in a team-building exercise with Ron Mumm, who at that time was the director of flight operations and chief pilot for BellSouth Aviation. As a Lieutenant Colonel in the Air Force, he had commanded the Thunderbirds demonstration team, a hand-picked group of the finest fighter pilots in the world. Ron credited his team’s outstanding performance to this continuous preparation-and-critique development concept. The Thunderbirds debriefed after every practice session and after every show by analyzing each maneuver. They integrated their ideas into a plan and put their plan into action the following day. Then they repeated the entire process. Ron often said, “Those who are passionate about performance must be passionate about critique and practice.”

Whether it’s the Thunderbirds, Blue Angels, Navy SEALs, Southwest Airlines, IBM, American Idol, or leadership development with a coach, this continuous development process is the proven way to raise performance levels. Talent is important, but talent without continuous development will quickly peak. To grow your skills so you can lead higher, you must first gain awareness. With knowledge you can plan, execute, and critique key components of every important action.

Since 2003, I have conducted ongoing leadership development processes with the senior team of Northeast Georgia Health System (NGHS) in Gainesville, Georgia. Carol Burrell, EVP and COO (now CEO), and Tracy Vardeman, VP Strategic Planning and Marketing, were the prime movers who kept this process going over a number of years. Our initial sessions focused on trust building, creative conflict, and emotional intelligence. Based on this information and on feedback from behavioral assessments, 360 assessments, and peer reviews, all participants created written development plans, shared their goals with peers, and participated in ongoing coaching. Along the way, they put into practice what they had learned, while regularly giving each other feedback on progress made and opportunities missed.

As the organization’s coach, I admired the strength and motivation of the leadership team. Their emotional maturity allowed them to be receptive to peer feedback and coaching, which in turn accelerated their personal and professional growth. Their teamwork and leadership seemed to be quite strong, but I was not sure how well they were performing compared to national standards.

Then, in 2010, the report card came in. Thompson-Reuters recognized NGHS as one of the nation’s “100 Top Hospitals.” What’s more, NGHS was one of only 23 in the 100 Top Hospitals to receive the Everest Award, which recognizes the boards, executives, and medical staff who have helped their organizations achieve the highest level of performance nationwide over the most recent five-year period.4 To top it off, Georgia Trend Magazine in December 2010 reported that Health-Grades Inc. ranked NGHS first in two out of eight clinical areas considered, and second in two more. These accomplishments are the result of the outstanding efforts of the entire health system staff and hospital community, but special credit must go to the senior leaders for their commitment to continuous personal and organizational improvement. Their leadership made a difference.

NGHS is one of many organizations that have validated the continuous development approach. Just as a screw or an auger provides a mechanical advantage with each turn, the Continuous Development Model gives individuals and teams a leadership advantage with each completed circuit. Like a spiral stairway, this model/process allows people and teams to climb higher and higher toward their full potential.

Foot Stomper: Authentic leaders engage in continual development. Knowledge alone is not enough; the only way to grow as a leader is to do things differently, and that requires change. Go first, and then take your people with you.

Foot Stomper: Authentic leaders engage in continual development. Knowledge alone is not enough; the only way to grow as a leader is to do things differently, and that requires change. Go first, and then take your people with you.

If you want your people to develop, set the example by engaging in ongoing development with them. The best way to lift your organization higher is to take what your team is learning and push it down to the people at the next lower level, so they can then push it down, and so on.

1. What would be the impact of you and your team leading at a higher level of effectiveness? How would it affect your time management? How would it affect your communications, decision-making, execution, and accountability?

2. What should you and your team be working on now? Like most world-class performers, you will probably need a coach. Who will facilitate your development process?

3. What would be the benefit of ongoing development as a standard practice at every level? Do you have a vision for that? What would it take to make it happen?

Note: To download an expanded version of these coaching questions for writing your responses, visit LeadingWithHonor.com.

1 After writing several drafts of this chapter, I read Unbroken, the best selling book by Laura Hillenbrand about World War II POW Louis Zamperini. He had similar experiences of a sharpened memory during his forty-seven day survival ordeal in a life raft in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

2 Lance Sijan was the first graduate of the Air Force Academy to win the Congressional Medal of Honor. Sijan Hall at the Academy is named in his honor. For more on Lance Sijan, read Into the Mouth of the Cat by Malcolm McConnell.

3 “Keys to Profitability: Lessons from Ratios Profit Leaders.” Graphic Arts Monthly, November 1, 2003.

4 NGHS Latest News, http://www.nghs.com/newsandevents.aspx?id=1646 (accessed February 5, 2011).