“Mission First, People Always”

U.S. Army Slogan

Military leaders have two primary responsibilities: to accomplish the mission and to care for the people. Balancing these two priorities can be difficult in normal times. In a wartime environment, with lives on the line, it can be a gut-wrenching challenge.

First and foremost is the accomplishment of the mission. In other words, job number one is to get the job done. Our mission in the air war was to stop the flow of supplies and troops from North Vietnam into South Vietnam. In support of this overall objective, I flew more than seventy combat missions (sorties) in Southeast Asia, and I was on my fifty-third mission over North Vietnam when shot down.

When I was captured, my mission immediately switched from offense to defense. The new objectives were to survive, to support my comrades, and to prevent the enemy from exploiting me in any way that would undermine the U.S. government and its war efforts. Stripped of my sidearm and my once-elegant flying machine, now scattered across hostile terrain, my only weapons were my mind, body, and spirit. I had experienced very realistic S.E.R.E (survival, evasion, resistance, and escape) training, so I understood my new mission, but I had no idea what sacrifices it would entail.

Early in the war, our POW leaders distilled our mission to six powerful words: “resist, survive, and return with honor.” Eventually, it was shortened to just “return with honor.” This short expression provided clear guidance, strong motivation, and benchmarks for measuring success. Although we desperately wanted to return home, returning in shame was an unthinkable option.1

As mentioned earlier, the Military Code of Conduct (see Appendix B) provided the practical framework for leading and serving with honor. Its six brief articles containing only 250 words provide broad guidance for virtually every scenario POWs face. First tested under fire in the Vietnam War, it proved to be an amazing document that clarified expected behaviors and set the boundaries for our resistance strategies.2

We found that the Code of Conduct had to be interpreted in light of the specific circumstances. How long should a person resist under torture before completing a biography or agreeing to read the propaganda news into a tape recorder to be played over the camp radio? Under what conditions should we try to escape? How much torture should someone take to avoid meeting with a peace delegation? These were not hypothetical issues that a detached executive in a remote, top-floor corner office would address for implementation by the rank and file. In the POW camps, the decision-makers knew they were likely to be the first to follow their own guidance.

Risner, Stockdale, and Denton had made it clear that we were to refuse to participate in propaganda broadcasts. But under extreme torture, it was impossible to totally resist. As we learned from the experience of several men who did not come home, at some point mind, body, and spirit break, causing loss of rational/coherent thought and the ability to effectively function. Therefore, Risner further clarified this policy by adding that we should “take torture indefinitely, but stop short of losing life or limb or mental facilities by falling back to a second line of defense.” Having been pushed beyond his endurance several times, he knew that sometimes temporary submission was the only way to preserve the ability to fight.

Because some POWs were simply tougher mentally and physically than others, local SROs had the freedom to interpret resistance policies to suit the circumstances. Major Larry Guarino (USAF), who heroically stood up to some of the worst treatment during the darkest days at the Zoo Camp, demonstrated wise discernment about how to effectively balance accomplishment of mission and care for the men. He said, “There are wide differences in people. A very few men, like Jim Kasler {Major, USAF} have the stamina and courage to stick to a hard line during severe punishment and continue to hold out. Most men, although they want to do a good job, will gamely resist the cruelties, but not for very long.”3

Although our leaders were often tortured first and most, they did not pretend to be macho “John Wayne” heroes. On the contrary, they openly shared the pain and despair of their brokenness, helping us understand the enemy’s tactics and the realities of what was and was not possible.4 It would have been disastrous for the mission and for their credibility had they been less than totally honest with us about their experiences in the torture chambers. Mutual accountability and transparency in the face of a cruel enemy bonded us tightly together.

An analysis conducted after the war by Headquarters USAF reflects the sacrifices and commitment made to achieve the mission:5

• Nine faithful warriors died before they could return with honor. We lost eight brave men due to extreme torture and deprivation in the earlier years, and one died of typhoid fever.

• More than 95 percent of POWs were tortured.

• Approximately 40 percent of POWs were in solitary confinement for more than six months; 20 percent were in solitary for more than a year; 10 percent were in solitary for more than two years; and several were in solitary more than four years.

Considering the length of stay and the crowded conditions, our survival record was remarkable. Most of us made it back, and our mental and emotional state exceeded the predictions of most of the mental health professionals advising DOD.6

The overall determination and devotion of this group to our mission was impressive. Of the nearly five hundred POWs in our network, fewer than ten (2 percent) willingly cooperated with the enemy. In these cases, our leaders meted out discipline, which could include denial of SRO status. Capt Ken Fisher provided this type of accountability regarding LtCol Minter, as we discussed in Chapter 2.

As we settled into an era of better treatment in 1970, the focus of the mission began to shift from resistance to survival. Most agreed that a belligerent attitude had been helpful to our cause and our psyche during the reign of terror, but when the enemy backed off on exploitation and adopted more of a “live and let live” policy, it was less advantageous to keep poking them in the eye.

Some of our leaders faced challenges from radical “hard liners” who saw it as their (and our) continuing mission to “give ’em hell” at every opportunity. A few men who had been rather timid during the hard times became inappropriately and recklessly brave when punishment was less likely. SROs had to walk a tightrope. They did not want to restrict fellow POWs from expressing their legitimate disdain for the enemy, yet they realized that antagonism could easily cross a line that would bring unnecessary reprisals on everyone in the cell, and even in the entire compound.

When we began living with forty to sixty men jammed into each cell, philosophical disagreements on routine issues of life occasionally ignited rebellious attitudes internally as well. As the V began to loosen their grip, some POWs who wanted more autonomy pushed back against our leaders and the tight command structure of Camp Unity. SROs maintained strict accountability and issued a few reprimands, always as privately as possible. Outside the individual cells, only those who operated the intra-camp “flagged” (secret) communications channel had any knowledge of these situations.

Close confinement for month after month, year after year sometimes caused tempers to flare and harsh words to fly. Most leaders, sensing the unique requirements of our family-like environment, showed extraordinary patience and compassion in dealing with interpersonal conflicts, offering a reminder when needed that our enemy was outside the cell. We were admonished to be quick to judge and manage our own shortcomings, while being tolerant of the faults of others. That would be good advice in any situation, but it was especially needed in captivity, where escape from neither friend nor enemy was an option.

Military leaders are taught to take care of their people, and the troops are taught to take care of their teammates. As we fought for survival against an enemy that was using every means to isolate, divide, and conquer us, we would willingly risk torture to support each other. The healthy took care of the sick, and the brave encouraged those more timid. When one man was down, the others did everything possible to lift him up.

Servant leadership was a way of life. LCDR Render Crayton spent six months in solitary because of his efforts to help save the lives of Smitty Harris and Fred Flom. SROs Risner, Stockdale, Denton, and others constantly pressed the V for better treatment and never hesitated to step into the breach on our behalf. In our cell at Son Tay, SRO Capt Ken Fisher was tortured for standing firm against our captors and for our cell’s generally “bad asstitudes,” much of which were attributable to Warner, Key, Stier, and me.

Even though the military emphasizes command and control, our SROs typically sought input before making decisions. For example, prior to issuing his famous BACK US policy, Stockdale reviewed his thoughts with cellmate Dan Glenn (LTJG, USN). He valued Dan’s counsel, even though he was a relatively new POW. At Son Tay, Ken Fisher always previewed and discussed his decisions with the rest of us. In Unity room 3, SRO Doug Clower routinely consulted with his six flight commanders and invited input from any of us. Thinking back, I am tremendously impressed by the way our leaders listened respectfully to our ideas. When they adopted some of mine, I felt valued far above what my junior ranking merited.

Our tough, results-oriented leaders also showed remarkable compassion toward those who had made mistakes. After we were settled in Camp Unity (the big rooms in the Hanoi Hilton), the senior leaders offered amnesty to some of the weaker men, who earlier had naïvely cooperated with the enemy, on condition that they commit to serving faithfully with us going forward. When some of the hardliners pushed back against this leniency, Risner and other longtime SROs responded by issuing a policy saying, “It is not American or Christian to nag a repentant sinner to his grave.” The amnesty stood, and on that basis almost all of the lost sheep came back into the fold. Unfortunately, two black sheep, one of whom was Minter, chose to remain allied with the enemy flock rather than rejoining ours.

The sacrificial service of our SROs continued after our repatriation. Even though they had been away from their families for six, seven, and even eight years, shortly after our return they devoted an entire week to completing formal evaluations describing how every POW had performed during captivity. This unselfish, voluntary, precedent-setting effort made a significant difference in our careers. In my case, it resulted in promotion to the rank of major two years ahead of my peer group.

Like all leaders, the SROs struggled to balance the often-competing demands of accomplishing the mission and caring for the people. Even as they pushed us to risk our welfare by resisting the enemy, they sought to minimize our suffering and injury. Their courage in pursuing the mission and their humility and concern for us under the most trying conditions won our hearts and earned our highest respect.

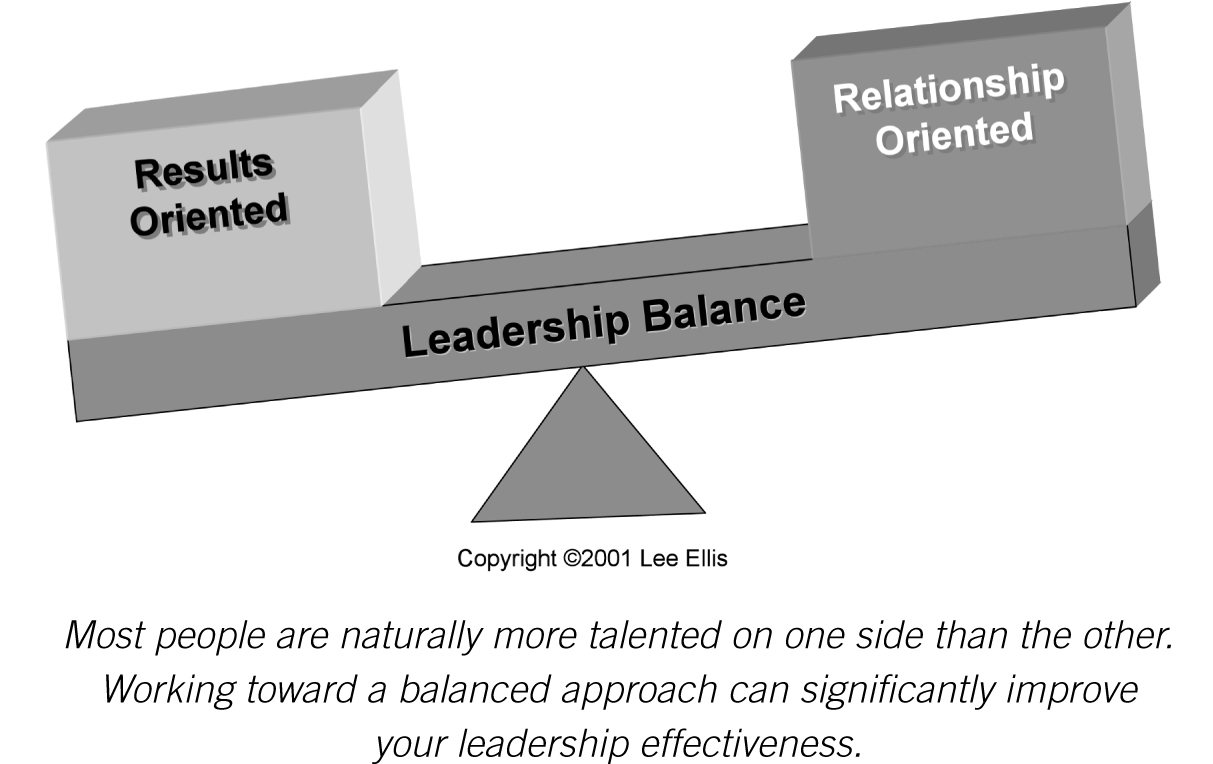

In civilian organizations, the terms “results” and “relationships” are more common than “mission” and “people,” so I’ll use them here. If results can be thought of as the head, or logical, side of leadership, relationships might be thought of as the heart, or feelings, side. Effective leaders understand that results and relationships, although often in tension, are both essential and complementary. To stay viable, you must get results. To get results, you must build relationships, because the energy and motivation that drive accomplishment comes from the hearts and emotions of people. Let’s examine some of the challenges to balancing these two important aspects of leadership.

Some leaders are inherently results-oriented. Although they are capable of being compassionate, they naturally are more focused on completing tasks, getting results, and achieving goals than on taking care of people.

Every organization exists for a purpose. If it fails to fulfill that purpose (accomplish its mission), it ultimately will cease to exist. In a very real sense, the business environment is a battlefield upon which life and death struggles are continuously waged.

Responsibility for an organization’s successes and failures, and ultimately its survival, falls squarely on the shoulders of its leader. Additionally, leaders who get results attract followers and accrue the power of influence. People want to be part of a winning team.

Results-oriented leaders

• See the big picture and provide vision

• Act decisively and give direction

• Communicate directly and behave in a straightforward manner

• Set high standards and clarify expectations

• Focus on tasks

• Solve problems

• Hold people accountable for their performance and actions

Unfortunately, results-oriented leaders often can be oblivious to the human side of the leadership equation. I witnessed a stark example of this problem when I was called in by the HR department of a division of a Fortune 500 company. A specialized unit of this organization, led by a group of results-oriented superstars, was highly regarded for its record of mission successes (results). Marring this record, however, was a formal complaint that had been filed by a lower-level team member about the organization’s “hostile” work environment.

As it turned out, I had known the senior manager earlier in my career as a person of good character. Being especially careful to keep an open mind, I conducted a number of interviews to gain insights into the issues that had caused the complaint. I learned that although no one had been treated unfairly, the extraordinarily high standards of the senior leaders, coupled with their stern accountability for missed goals, had created an extremely tense, demanding, and fearful atmosphere, primarily among the lower-level employees.

Because this unit regularly hosted and provided services to the organization’s CEO and other officers, the managers had established higher standards for dress and decorum than were in effect in the rest of the company. Some younger associates at the lower levels did not understand why these “looking sharp” policies were necessary, and they felt unfairly punished when they didn’t personally comply. When faced with questions and challenges from below, the leaders made matters worse by applying their natural results-oriented skills with greater intensity.

Prior to conducting a leadership class, I asked members of the senior team to complete a personality assessment. These leaders were fine people with good values, but the test revealed them to be the most results-oriented group I had ever encountered. In fact, when they reviewed their reports, they were stunned to see how much their natural “results” strengths outweighed their “relationship” strengths. They tended to be highly challenging, very direct, and impatient hard-chargers who were generally poor listeners and unaware of the emotions and feelings of others. These tendencies were further exacerbated by their high-pressure, results-oriented work environment.

Don’t be too critical of these leaders. Under pressure, we all have a tendency to fall back on our strongest innate traits and familiar habits. If they have served us well in the past, why not turn to them again? Abraham Maslow explained this phenomenon by saying, “If all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.”

Results-oriented skills are essential, but they must be balanced with relational skills. If you are naturally results-oriented, adding relational abilities to your leadership repertoire may feel unnatural at first. But acquiring any new skill—whether it’s learning to dance, ride a bicycle, or speak a second language—initially feels awkward. So, if you think that you might need additional capabilities in your leadership toolbox, be courageous, lean into the pain, and develop the skills you lack. That’s what the leaders of this organization did, and the work environment gradually improved.

Relationship-oriented leaders instinctively focus on developing and supporting others. Through the natural application of their talents and behaviors, they create environments that cultivate loyalty and allow people to thrive in their work over the long term.

Relationship-oriented leaders

• Listen well

• Show respect for others

• Give encouragement and feedback

• Demonstrate compassion, care, and concern for people

• Trust people to do their jobs

• Support people and lend a helping hand

• Help people develop their talents

Leaders who emphasize relationships motivate and inspire their followers to achieve success, because those behaviors touch the deepest desires of human beings: to be valued, to be respected, to have significance, to make a difference, to be accepted, to be part of a larger purpose, to be in community, to be treated fairly, and to hear “well done.” Exercising relationship skills is as natural to these leaders as floating downstream.

However, excessive emphasis on relationships can cause problems. That was certainly the case with a unit of a large company we were called in to help. It didn’t take long to come to the conclusion that most of the issues facing this organization’s executive team related to the leadership style of the senior manager. He was very popular, but his followers sensed that their unit was losing influence in the company because it was failing to make the desired impact. The more results-oriented members were very frustrated with this leader’s lack of vision and decisiveness. Since they lacked any authority to take control, they were mentally and emotionally checking out.

We met with the leader before the scheduled team session to review his personality assessment, which showed that he was strongly people-centered. While discussing his profile and the struggles of his team, he suddenly exclaimed, “I think I see the problem: it’s me. I gravitate toward relational things, and I dislike dealing with some of the tougher issues like clarifying next steps, setting deadlines, and competing for funding in the company. I want to keep everyone happy and avoid conflict, so I try to get 100 percent agreement on every issue, and I don’t hold people accountable for timely results.”

Needless to say, we were impressed with this manager’s remarkable honesty, humility, and insight. And I was equally impressed with his subsequent efforts toward becoming a better-rounded leader. Although changing his style took time and effort, he made enough progress to turn his team around and become more viable in the organization. In the process, he learned to better use the talents of the more results-oriented people around him.

Over a period of years, I surveyed more than three hundred managers to find out what traits were present in the leaders they identified as outstanding. Two important insights emerged:

• Although all survey participants acknowledged the importance of achieving results, the great majority said they remembered their best leaders more for their relationship skills. In fact, even among those who considered themselves primarily “results-oriented,” 80 percent identified a relationship skill from the list above as the most outstanding characteristic of their best leader.

• A willingness to listen was the leadership trait people respected most in their leaders.

Even the best relationship skills cannot keep everyone satisfied, because relationships alone do not satisfy. People want and need to achieve worthwhile goals. They desire leaders who will establish boundaries and exhibit the tough love that they sometimes need to grow and excel. Effective leaders are always working both sides of the equation to meet the seemingly competing needs of mission and people.

If people were computers or machines, leaders could focus entirely on results and push their followers 24/7 to achieve maximum output. But as Ken Blanchard and Marc Muchnick so well illustrate in their fable, The Leadership Pill: The Missing Ingredient in Motivating People Today, focusing entirely on achievement succeeds only for a short period. If prolonged, it will actually hinder results. On the other hand, a more balanced approach that focuses on results and people allows organizations to reach their fullest potential.

Leaders who balance the competing demands of results and relationships are able to push for the achievement of goals, while eliciting the best from their people. It’s as if they have two bank accounts. They make deposits in their “results” account by consistently accomplishing their goals, and they build up capital in their “relationship” account by caring for their people as individuals of worth. In the first instance they earn credibility with their superiors, and in the second they earn loyalty from their followers.

Occasionally leaders will need to make withdrawals from these bank accounts. For example, a leader who is being pressured by unrealistic expectations from above may need to draw on the credibility she’s accumulated in her “results” bank account and say to her superiors, “We need to adjust this timetable, or we’ll burn out our people.” At other times she may have to make a withdrawal from the relationship bank account and say to her team, “We’ll have to work over the weekend to get this job done.”

With regard to balancing mission and people, Admiral Stockdale wisely said, “A leader must remember that he is responsible for his charges. He must tend his flock, not only cracking the whip, but ‘washing their feet’ when they are in need of help.”7

Balancing “results and relationships” is a major leadership challenge. Some leaders are naturally gifted with the head (logic) and not very good with the heart (feelings). Others are just the opposite. Only about 20 percent of the population has a natural ability with both. Even those with this “tightrope-walking” capability often end up tilting toward a results-oriented style, because results are typically what get noticed and rewarded.

If your leadership style is unbalanced, the good news is that you don’t have to reinvent yourself. (That would be impossible anyway!) To gain better balance, you simply have to develop some of the skills you lack. Put simply, you may either need to “toughen up” or “soften up.” This may sound artificial, but with practice your adapted behaviors will feel more comfortable. They will never become totally natural, however, so you’ll have to consistently and intentionally work at keeping your balance.

Most leaders can dramatically increase their effectiveness by simply gaining a better balance between results and relationships. Use this framework as you observe your own leadership and the styles of others. Becoming more aware of this dynamic will enable you to coach yourself into a better balance that will result in a higher level of performance.8

Foot Stomper: Outstanding leaders balance accomplishment of the mission (results) and care for their people (relationships). However, the styles of most leaders are naturally biased toward one end of the spectrum or the other. To enhance your leadership effectiveness, find out which types of skills you need to develop. Then, leaning into the pain of your doubts and fears, adapt your behaviors to do what you know a good leader should do.

Foot Stomper: Outstanding leaders balance accomplishment of the mission (results) and care for their people (relationships). However, the styles of most leaders are naturally biased toward one end of the spectrum or the other. To enhance your leadership effectiveness, find out which types of skills you need to develop. Then, leaning into the pain of your doubts and fears, adapt your behaviors to do what you know a good leader should do.

Coaching: BALANCE MISSION AND PEOPLE

Coaching: BALANCE MISSION AND PEOPLE

Do you tilt toward results or relationships? If you’re unsure, look at the list of strengths for each in this chapter and see which feels more natural and comfortable for you. Or, for a more comprehensive look, you may want to complete the online N8Traits assessment (link at LeadingWithHonor.com). It will provide insights into your leadership strengths, so you’ll know whether you tend to favor results or relationships.9

1. How can you develop your leadership balance? Once you know your natural traits, identify two behaviors (skills) from the other list in this chapter that you could work on to better balance your leadership style. For example if you are naturally results-oriented, skills in that list will come easy. To gain a better balance look at the list of relationship-oriented skills and select two that you could work on to gain a better balance in your leadership.

2. What will be the payoff to you if you learn to use these new leadership behaviors? When will you begin practicing your new behaviors?

3. What would be the impact if all your leaders gained a better balance of results and relationships (mission and people)? How could you make that happen?

Note: To download an expanded version of these coaching questions for writing your responses, visit LeadingWithHonor.com.

1 Jamie Howren and Taylor Baldwin Kiland, “Vietnam POWs Thirty Years Later,” http://www.opendoorsbook.com/message.php (accessed April 6, 2011).

2 Robert K. Rule, “The Code of Conduct,” http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/au-24/ruhl.pdf (accessed October 12, 2010).

3 Larry Guarino, A POW’s Story: 2801 Days in Hanoi. (New York, NY: Ballantine Books, 1990) 166.

4 Shortly after our release, President Nixon hosted the POWs at the White House for the largest Gala ever held there. Hollywood stars sat at each table. Colonel Larry Guarino told his table host, actor John Wayne, that initially he had responded to the V like he thought John Wayne would have. Duke asked him, “What happened?” Guarino responded, “They beat the s__t out of me.” His response brought tears to Duke’s eyes. Guarino, 165.

5 HQ USAF/XOX Study, SEAsia PW Analysis Program Report, Washington DC, 1974.

6 Two months after our release, I met with Holocaust survivor and Psychiatrist Dr. Victor Frankl who had served on a Department of Defense Advisory Board consulting on what to expect on our release. He said, “Many of my colleagues were very worried, but I told them you would be okay.”