Figure 7. M. Agrippa was Augustus’ right-hand man and closest friend. The man who brought him victory at Actium continued to command in other campaigns around the world until his death.

Ti. Claudius Ti. f. Nero I P. Quinctilius Sex. f. Varus

When the road to Italy became passable in the spring, Augustus set off for Rome. He was confident that affairs in the Hispanic and Gallic provinces were settled and that Drusus was fully capable of leading the coming invasion of Germania.1 Already in the city of seven hills his brother Tiberius had been sworn in as consul alongside P. Quinctilius Varus, the former legate of Legio XIX who had served with him in the Alps two years before.2 Augustus himself arrived in Rome at night – which was his usual practice – to avoid the unwanted attention of senators and common people; and when it was revealed he had come home he declined a proposal for an altar to be placed in the Curia Iulia to commemorate his safe return (adventus).3 The following day, he welcomed guests at his home on the Palatinus Hill for the customary salutatio. After the morning’s social obligations were dealt with, he climbed the steps to the Capitolium, where he removed the laurels from around his fasces and placed them in gratitude upon the knees of the statue of Jupiter in the temple.4

As princeps, Augustus convened a session of the Senate to discuss important business. His time away from Rome and in the company of his legati had allowed him to think deeply upon many matters of state. Finding his voice to be hoarse, he passed the handwritten speech to the quaestor who read it aloud on his behalf.5 He gave the Conscript Fathers an account of his recent tour of his provincia. Then he presented a proposal for reforms to army terms of service, pay and retirement benefits. His purpose was clear: explicitly defining the conditions and rewards of life in the military would mitigate against the risk that soldiers might contemplate mutiny as a means to negotiate improvements to their lot.6

Firstly, he reduced the years of service in the Cohortes Praetoriae from sixteen years to twelve, and set the number at sixteen for the legions and auxiliaries.7 Secondly, he made adjustments to salaries and the cash lump sum paid at the end of their service instead of the land grant, which the regular troops were always demanding.8 Dio comments:

These measures caused the soldiers neither pleasure nor anger for the time being, because they neither obtained all they desired nor yet failed of all; but in the rest of the population the measures aroused confident hopes that they would not in future be robbed of their possessions.9

The proposal was accepted.

Witnessing the rate of progress in quelling the unruly territories by the armies operating under Augustus’ auspices, many senators might have imagined they would soon see the return of more Provinces of Caesar into their care. In optimistic mood, on 4 July the Senate voted for an altar to Pax Augusta – ‘the revered pact’ or ‘August Peace’.10 It would be erected on ground a mile outside the pomerium beside the Via Flaminia and become a prominent feature of the Field of Mars. The ceremony to consecrate the ground for the altar was held the same year.

Augustus initiated another purge of the Senate.11 In the aftermath of the Civil War, the Senate had seen its numbers shrink drastically. The financial qualifications to enter the body had been reduced to HS400,000 to allow less wealthy men to join, but over a decade the Senate membership had grown and the asset limit was again raised to HS1,000,000 to reduce the number eligible. However, the substantial increase had succeeded too well; now many gifted, but impoverished, younger patricians failed the wealth test while others who were qualified pretended they were below the limit in order to avoid joining.12 If Augustus did nothing his talent pool was at risk. To address the matter he took direct action:

Augustus himself made an investigation of the whole senatorial class. With those who were over 35 years of age he did not concern himself, but in the case of those who were under that age and possessed the requisite rating he compelled them to become senators, unless one of them was physically disabled. He examined their persons himself, but in regard to their property he accepted sworn statements, the men themselves and others as witnesses taking an oath and rendering an account of their poverty as well as of their manner of life.13

His timely intervention would create opportunities in public service for a new generation to replace the one loyal to Augustus that was aging and taking a less active role in public life – older men like Cornelius Balbus, Norbanus Flaccus, Valerius Messalla Corvinus, Silius Nerva and Statilius Taurus.

The most distinguished member of this old guard, M. Agrippa, returned this year from his mission in the East. His imperium was authorized for another five years along with Augustus’, ‘entrusting him with greater authority than the officials outside Italia ordinarily possessed’.14 There could be no doubting now among detractors – and there were many in the ranks of nobiles – that Agrippa was Augustus’ right-hand man, the one he trusted above all others (fig. 7).15

While work on the infrastructure for the coming Bellum Germanicum proceeded apace, a year into Drusus’ governorship of Tres Galliae, a violent conflict erupted involving the Aquitani in the Pyrennees. A military response was required and one ensued, the details of which are entirely lost.16

In Thracia, a political assassination upset the fragile peace in the kingdom friendly to Rome.17 A priest of the cult of Dionysus named Ouologaisis (Vologaesus) of the Bessi nation gained a popular following by practising clairvoyance.18 Inspired by him, his adherents rebelled and in the ensuing chaos King Raiskuporis (Rhascuporis) I, son of Kotys I, was killed. Playing on his reputation for having a supernatural power, he stripped Roimetalkes (Rhoemetalces) I – the victim’s uncle – of his army without a battle. This was a catastrophe, for, as Florus records, ‘he had accustomed the barbarians to the use of military standards and discipline and even of Roman weapons’.19 Their training alone should have taught them to stand their ground; instead they deserted their ensigns. In pursing the Thracian king, Ouologaisis crossed into the Chersonese, where he wrought havoc. Separately, but at the same time, the Sialetae nation was running amok in Macedonia, its governor apparently absent.20

Figure 7. M. Agrippa was Augustus’ right-hand man and closest friend. The man who brought him victory at Actium continued to command in other campaigns around the world until his death.

Meanwhile, the impact of M. Vinicius’ victory in Illyricum proved short-lived. The confederacy of the nations of the northern Balkans rose up again. Alerted to the fact that his legate was seemingly unable to contain the insurrection, Augustus sent his 50-year-old best friend to supervise combat operations.21 Agrippa departed for the war zone in spite of the fact that it was already winter. His reputation went before him. ‘The Pannonii became terrified at his approach,’ writes Dio, ‘and gave up their plans for rebellion.’22 There was no reason for him to stay any longer than absolutely necessary. Hardly had he arrived when he began making his preparations to return home.

| M. Valerius M. f. Messalla Barbatus Appianus | P. Sulpicius P. f. Quirinus | |

| suff. | C. Vagius C. f. Rufus | |

| suff. | C. Caninius C. f. Rebilus | L. Volusius Q. f. Saturninus |

In the early weeks of the new year, M. Agrippa embarked on the journey back to Italy.23 He did not stay in Rome, however, but proceeded directly to his summer house in Campania. Shortly after arriving, he fell ill and took to his bed.24 His adjutants sent a message to Augustus requesting him to come urgently. When the princeps finally arrived he found him already dead.25 Tragically, Fate had intervened to prevent the old friends from exchanging final words. Augustus personally arranged for the body to be carried to Rome, where it was laid in repose. Following a grand funeral procession, which moved through the city to the Forum Romanum, he gave the eulogy himself, part of which has survived.26 After the corpse had been cremated, the urn containing the ashes was placed in Augustus’ own mausoleum, despite Agrippa having already build a sepulchre for himself on the Campus Martius.27

Agrippa’s sudden death was a devastating loss to Augustus personally, but also to the Res Publica. He had been Augustus’ best friend for over thirty years, his most trusted political associate and the nation’s greatest military commander. Augustus urgently needed a new ‘right-hand man’. He found him in his eldest stepson, Ti. Claudius Nero (plate 23).28 In many ways he was like the late Agrippa – a battle-tested field commander, a proven diplomat, and he was selfdisciplined, hardworking, trustworthy, modest and reliable. To cement the relationship, Augustus required Tiberius to divorce his present wife (a daughter of Agrippa) and marry Augustus’ daughter, Iulia (now the widow of Agrippa).29 The forced separation from the woman he loved affected him deeply.30 Despite his protests, Tiberius resentfully complied.31 Between grieving for Agrippa and marrying Tiberius, Iulia Caesaris gave birth to a son named M. Agrippa (better known to History as Agrippa Postumus).32

Tiberius’ combat leadership skills were soon pressed into action when the nations of northern Illyricum rebelled again.33 He did not yet have the name recognition of Agrippa with its pacifying effect among these people, which meant he would have to go and wage war against them in person. To assist him he was able to call up on the Scordisci, long-term allies of the Romans (and one of the largest tribes in the western Balkans) as well as neighbours of the rebels.34 The warriors of the two nations were similarly equipped and fought in similar fashion.35 The armed Scordisci, Roman legions and auxiliary cohorts together unleashed a brutal counteroffensive. The alliance proved highly effective. ‘Tiberius subdued them,’ writes Dio, ‘after ravaging much of their country and doing much injury to the inhabitants.’36 As he had with the Raeti, ‘he took away the enemy’s arms and sold most of the men of military age into slavery, to be deported from the country’.37 The annual demand of payment of tribute was imposed on those remaining.38 Eager for news of the campaign, Augustus had, in the meantime, relocated to Aquileia.39 Receiving the report of the successful outcome of the war, the Senate voted Tiberius a full triumph. For Augustus, however, giving the highest military award to the 30-year-old commander was too much too soon: he did not permit his stepson either to accept or celebrate it. Instead, ‘he granted him the triumphal honours’.40

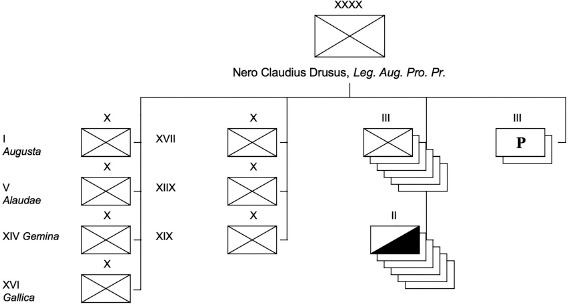

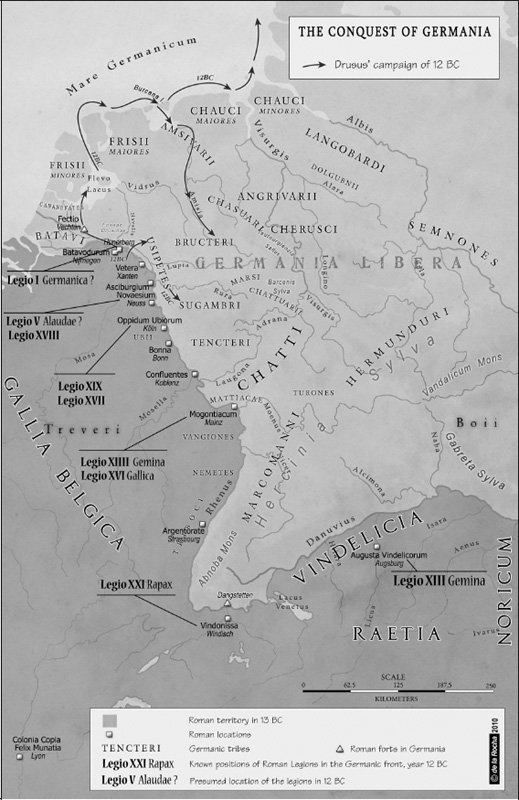

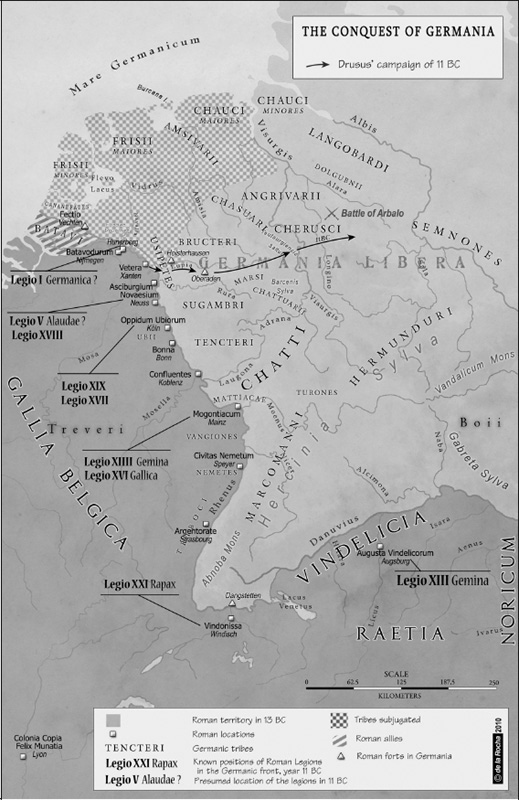

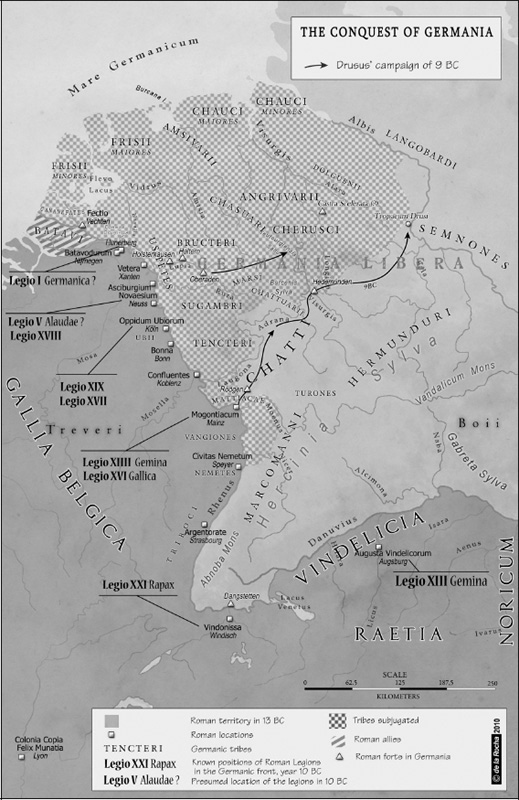

In Tres Galliae, Tiberius’ 26-year-old brother was about to launch his invasion of Germania with his massive army (see Order of Battle 2). Intelligence reached him that several of the Gallic chieftains were planning a rebellion, apparently in concert with certain Germanic nations led by the Sugambri.41 Drusus had to move quickly or his invasion plan would be in jeopardy. He contrived to invite the leaders of the sixty nations to a special meeting of the Concilium Galliarum at Colonia Copia Felix Munatia. The ploy worked and the rebellion was extinguished before it could take place. Meanwhile, he waited for the Germans to cross the Rhine and, when they did, repulsed them. With his rear secure, Drusus now gave the order to proceed with the war. Two years in the planning, the Bellum Germanicum had begun.

Order of Battle 2. Germania, 12–9 BCE. Units of ethnic auxilia are recorded as having served in Germania, including Cohors Batavorum, Cohors Canninefatium, Cohors Raetorum, Cohors Vindelicorum and Cohors Ubiorium. There were also alae, including Ala Frisiavonum.

The opening move of the first year’s offensive was a punitive attack on the perpetrators of the Clades Lolliana of 17 BCE and the recently failed Gallic revolt (map 10). The Roman incursion was launched from the legionary base at Batavodurum. In the spring, the expeditionary force crossed the Rhine and marched south along the right bank of the river, then veered left into the country of the Usipetes and their target, the Sugambri.42 Drusus’ men were ordered to devastate their countryside (vastatio). The destruction of their agricultural capability – forcing the tribe to make repairs or risk losing their crops later in the harvesting season – would ensure they could not be active participants in the war this year.

The main thrust of the campaign was directed at the nations on the west coast of Europe. Dio writes that Drusus now ‘sailed down the Rhine to the ocean’.43 The newly constructed fossa Drusiana provided safe passage for the fleet of transports into Lacus Flevo, which, in Drusus’ time, was about half the size of the modern IJsselmeer. The ships were rowed by the legionaries themselves, who had to take care to navigate as they went.44 Oak trees lined the banks of the lake. Many had been toppled by high winds and floated in the lake, posing a danger to the lightly built Roman craft.45 Making landfall each night on the voyage allowed the men and animals time to rest and recuperate for the next leg of the journey.

En route, Drusus made contact with the local inhabitants of the region. There was much to be gained by making an ally out of an adversary: he could provide men to supplement the army; pilots to navigate unfamiliar seas; and translators to aid in understanding other tribes. The local people were the Cananefates and Frisii. Drusus ‘won over the Frisii’, writes Dio, and signed a treaty with them (fig. 8).46 During this and subsequent campaigns, men of the Frisii served with the Romans as auxiliary infantry in the Cohors Frisiavonum.47 From now on they would provide tribute (tributum) in the form of cow hides for the Roman army.48

Map 10. Military operations in Germania Magna, 12 BCE.

Figure 8. Nero Claudius Drusus presents Germanic prisoners of war and hostages to Augustus, who is seated, in a scene on a silver cup. Unconditional surrender was a prerequisite for a declaration of victory.

From the relative calm of Lacus Flevo, Drusus’ fleet sailed into the region now called the Wadden Sea. Drusus ‘subjugated, not only most of the tribes, but also the islands along the coast’, writes Strabo, ‘among which is Burchanis, which he took by siege’.49 Reaching the Dorlar Estuary, the fleet berthed and its crews disembarked. A few ships, however, sailed on to Jutland, apparently on a voyage of exploration, making Drusus ‘the first Roman general to sail the northern Ocean’.50 He might have gone further:

Drusus Germanicus indeed did not lack daring; but the Ocean barred the explorer’s access to itself and to Hercules. Subsequently no one has made the attempt, and it has been thought more pious and reverential to believe in the actions of the gods than to inquire.51

The Roman navy had never sailed this far north – and would never again.

The main body of the expeditionary force disembarked at the Ems (Amisia) River.52 Drusus then ‘invaded the country of the Chauci’, the people who lived in what is now called Lower Saxony (Niedersachsen), who were regarded as the noblest Germanic people, but were impoverished by living on the coastline.53 His fleet sailed down the Ems until it reached the land of the Bructeri, where a battle was fought on the river. Roman ships came under attack from missiles lobbed from the banks and small boats. The outcome was ‘Drusus won a naval victory over the Bructeri’, writes Strabo, probably with some hyperbole (plate 28).54 On the return, Drusus’ captains misjudged the tides and several ships of his fleet ran aground on the mudflats of the Wadden Sea.55 His new allies proved their worth when the Frisii helped rescue the stranded vessels and the army was able to reach its camps along the Rhine before winter set in.56 Minor setbacks notwithstanding, Augustus’ youngest stepson was proving to be a living example of the best of Roman values. Upon his arrival in Rome, in recognition of his bold endeavours, Drusus was promoted to praetor urbanus.57

In the same year, M. Iulius Cottius, who was king of the Ligures (a nation inhabiting the mountainous region of the western Alps known as the Alpes Cottiae), agreed a treaty with Augustus. He was son of King Donnus, who had initially opposed, but later made peace with, Iulius Caesar.58 Cottius – and his own son of the same name after him – would continue to retain power at his seat at Segusio (Susa), but as client kings of the Romans. Crucially, this secured the road between Augusta Taurinorum (Turin) and Brigantium (Briançon), connecting Gallia Cisalpina to Narbonensis.59

In stark contrast, the situation in Thracia was worsening. To avert disaster, Augustus ordered L. Calpurnius Piso (plate 22), Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore of Galatia-Pamphylia, to march against the rebels.60 Consul of 15 BCE, Piso had the complete confidence of the princeps: he was from an old plebeian family promoted to the patriciate, an independent-minded man whose virtue, tact and personal achievements were widely praised.61 Velleius Paterculus had kind words for him:

All must think and say that his character is an excellent blend of firmness and gentleness, and that it would be hard to find anyone possessing a stronger love of leisure, or, on the other hand, more capable of action, and of taking the necessary measures without thrusting his activity upon our notice.62

When the rebels learned that Piso was approaching, afraid of certain defeat they retreated homeward.63 In his war against Ouologaisis and the Bessi, the Roman commander initially suffered reverses, but true to his character he would not give up until he had achieved his mission. The fortune-telling usurper had not, apparently, foreseen his own defeat.

At home, Augustus sponsored traditional paramilitary exercises. This year the Lusus Troiae coincided with the dedication of the Theatre of Marcellus.64 To be held every four years, these ‘Troy Games’ were a display of mock combat routines performed on horseback by freeborn equestrian Roman boys of different ages in the Circus Maximus.65 Also known as Circensian Games, they were Augustus’ favourite public spectacle, ‘thinking that it was a practice both excellent in itself, and sanctioned by ancient usage, that the spirit of the young nobles should be displayed in such exercises’.66 A particular crowd-pleasing attraction was C. Caesar, the 9-year old adopted son of Augustus, who took part in them for the first time. Embarrassingly for Augustus, during the show ‘the joints of his curule chair happening to give way, [and] he fell flat on his back’.67

Q. Aelius Q. f. Tubero Paullus Fabius Q. f. Maximus

With the western sector of Germania invaded and treaties signed with several of its peoples, in the second year of the Bellum Germanicum Drusus opened up a new front. At the start of spring his army crossed the Rhine again, but marched into the central region of Germania, beginning with the territory of the Uspietes (map 11). Their resistance collapsed quickly and, having received their surrender, the Romans marched on. As the Romans approached, the Sugambri raised no opposition. They were not there but, in fact, away raiding the lands of the neighbouring Chatti nation to the east. Dio reports that the Sugambri were angry at them for having refused to join their alliance against the Romans, and ‘seizing this opportunity, Drusus traversed their country unnoticed’.68

Map 11. Military operations in Germania Magna, 11 BCE.

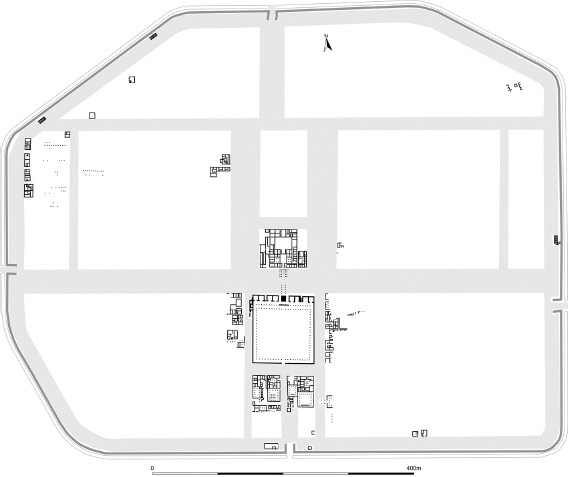

As he advanced towards the Weser River (Visurgis), temporary marching camps, semi-permanent garrison forts and supply dumps were erected at intervals of roughly 18 kilometres – or a day’s march – along the course of the Lippe River. Located 36 kilometres (22 miles) from Vetera on the north bank of the river was Holsterhausen, a marching camp roughly rectangular in shape with a V-shaped ditch and encompassing a space of 50 hectares, able to accommodate up to two legions and auxiliaries.69 Some 54 kilometres (36 miles) east of Vetera lay Haltern. The site was initially occupied with a temporary camp covering 34.5 hectares – enough space for two legions – and a fortlet upon a hill called the Annaberg.70 Some 15 kilometres (9 miles) east of Haltern stood Olfen. Storing food and matériel was the likely purpose of this fortified site of 5 hectares, large enough for one or two cohorts.71 Nearby, the river was crossed by a bridge; Dio refers to it when writing that Drusus ‘bridged the Lupia and invaded the country of the Sugambri’.72 The chain of installations continued up river, but the forts were now sited on the opposite bank. At Beckinghausen, a small fort of 1.56 hectares with triple ditch on the three sides facing inland was erected, its purpose perhaps being to receive supplies delivered by boat for transportation overland.73 Just 2 kilometres (1 mile) southeast of it – and some 90 kilometres (56 miles) from Vetera – was the fortress at Oberaden. Roughly oval in shape, at 56 hectares it was an enormous fortress, able to house up to two legions and auxiliaries (map 12).74 This year Roman engineers began to lay out the foundations of its essential infrastructure, such as water tanks and the main internal buildings which would, over the next two seasons, be fabricated of wood. The strongly constructed defences and gates at Oberaden indicate the Roman high command intended the army to stay a while.75

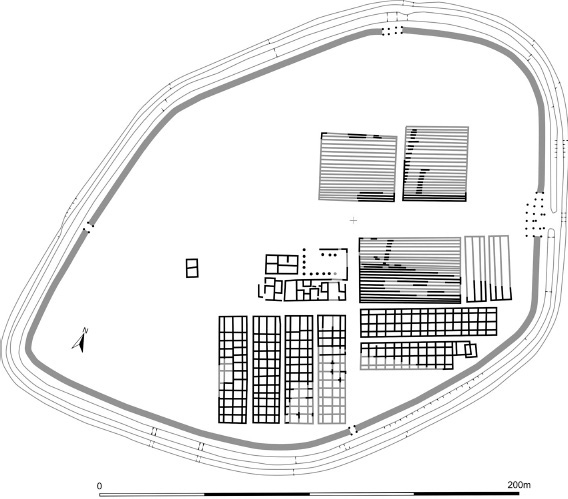

Elsewhere, above the Wetter – a tributary of the Main River – in the territory of the Mattiaci, a supply dump was erected on the edge of a plateau at Rödgen.76 Within its polygonal plan encompassing 3.3 hectares, three large granaries were installed to store grain and other commodities shipped up river from Mogontiacum (map 13). This would ensure the army advancing northeast towards the upper section of Weser was fed and equipped.

Progress through Germanic territory was swift. One curious incident that unsettled the military high command – so much so it was considered important enough to be recorded by several Roman historians – involved a portent:

In Germania in the camp of Drusus a swarm of bees settled on the guy ropes and posts of the tent of Hostilius Rufus, praefectus castrorum.77

Map 12. Oberaden Roman Fort, Germany.

The augur interpreted the phenomenon as a bad omen and predicted a coming ambush;78 but when, and where? The forewarning was obscure, as was so often the case with omens. Just as the campaign season was drawing to a close, the army reached the Weser.79 Far into enemy country, Drusus’ supplies were now running perilously low. Wise counsel prevailed and he gave the order for the march home.80

The columns of his expeditionary force, extended over many miles, came under constant attack. Exploiting the element of surprise, the Germans rushed out from the cover of forest and dense undergrowth to strike at soldiers, pack animals and the others who followed the Roman army to war. Germanic warriors fought both on foot and horseback. Their preferred weapon was the framea, which, according to Tacitus, was a spear with a ‘narrow and short head’.81 It could be thrown long distance, or thrust or swung at close quarters and, in the trained hands of an experienced warrior, could inflict damage even against a heavily armoured legionary wearing chain mail (though the new articulated plate armour afforded better protection).82 Nevertheless, the Romans pushed ahead. At a place called Arbalo, Drusus’ army came under the most intense attack of the campaign. It was a pass that forced his troops to march along the bottom of the narrow defile. The Germans blocked off his escape routes, front and rear, and used the higher ground to devastating effect. Pressed together and burdened by their carry packs (sarcinae), the Roman legionaries struggled to deploy in formation and use their pila or gladii. Dio writes that ‘once they shut him up in a narrow pass and all but destroyed his army’, but then, almost as suddenly as they had staged their offensive, it seems the Germans had a last-minute change of heart:

Map 13. Rödgen Roman Fort, Germany.

They would have annihilated them, had they not conceived a contempt for them, as if they were already captured and needed only the finishing stroke, and so come to close quarters with them in disorder. This led to their being worsted, after which they were no longer so bold, but kept up a petty annoyance of his troops from a distance, while refusing to come nearer.83

The Germans let pass the opportunity to destroy the invaders. It was an unexpected stroke of good luck for Drusus. The Romans claimed the battle as a success on account of their prowess in the arts of war. Indeed, polymath and former military officer Pliny the Elder praises ‘commander Drusus when he gained the brilliant victory at Arbalo’, adding that it is:

a proof, indeed, that the conjectures of soothsayers are not by any means infallible, seeing that they are of opinion that this is always of evil augury.84

For their part, the common soldiers enthusiastically acclaimed their 26-year-old legate as imperator.85

Strategically, it was important that Drusus establish a permanent military presence in the region and ‘to secure the province he posted garrisons and guardposts all along the Mosa, Albis and Visrurgis’.86 He erected a new fort at the confluence of the ‘Lupia and Elison rivers’ (known by the name Aliso) and a second one in the territory of the Chatti (whose location is still disputed).87 Units previously headquartered on the Rhine now began relocating to the forward operating base at Oberaden.88 It was the first time that garrisons of Roman troops would spend an entire winter in their cramped goat skin tents (nicknamed papiliones, ‘butterflies’, by the soldiers) on German soil.

The news of Drusus’ achievement was well received in Rome:

For these successes he received the triumphal ornaments, the right to ride into the city on horseback, and to exercise the powers of a proconsul when he should finish his term as praetor.89

However, Augustus refused to allow Drusus to keep the appellation of imperator – just as he had done with his older brother.90 The victory at Arbalo had been won under his auspices and, as was his privilege, the princeps added it to his own list of acclamations, which had grown to a cumulative total of twelve.

This year, Tiberius was once again called upon to intervene in Illyricum. While he and the larger part of his army was away, first the Dalmatae on the coast, and later the tribes collectively known as Pannonii in the hinterland, revolted.91 No details of the war have come down to us, save a general description. Dio writes only that Tiberius swiftly returned to the region and made war upon both of them simultaneously, dividing his time between one front and then the other. It was a validation of the Senate’s decision in 22 BCE to transfer the province to Augustus, ‘because of the feeling that it would always require armed forces both on its own account and because of the neighbouring Pannonii’.92

In Thracia, Piso recovered from his early setbacks and succeeded in conquering both the Bessi and the neighbouring nations who had taken part in the rebellion.93 To break the revolt, the resourceful commander had applied a variety of approaches, including compromise:

At this time he reduced all of them to submission, winning over some with their consent, terrifying others into reluctant surrender, and coming to terms with others as the result of battles; and later, when some of them rebelled, he again enslaved them.94

Florus recounts the same events of the Bellum Thracicum with his customary dramatic imagery:

Though subdued by Piso, they showed their mad rage even in captivity; for they punished their own savagery by trying to bite through their fetters.95

Summing up the campaign, which took three years to conclude, Paterculus writes with a somewhat broader perspective:

As legatus of Caesar [Augustus] he fought the Thraci for three years, and by a succession of battles and sieges, with great loss of life to the Thraci, he brought these fiercest of races to their former state of peaceful subjection. By putting an end to this war he restored security to Asia and peace to Macedonia.96

For these successes the Senate voted him thanksgivings (supplicationes) and ornamenta triumphalia, but not a full triumph.

The positive news flow kept Augustus’ popularity high among the Roman People. The Senate remained under his close scrutiny. He conducted a census of the population and, having carried out an audit of attendances of sessions of the house, ruled that the Senate could pass legislation with fewer than the required quorum of 400 members.97 The People insisted on paying for statues of Augustus to be erected in the city, but he declined the offer, preferring instead to see the money invested in images of the divine trio of Salus Publica, Concordia and Pax – ‘Public Heath’, ‘Harmony’ and ‘Peace’. When his sister Octavia died that year, she was accorded a public funeral in Rome. Both Drusus and Tiberius gave eulogies.98

Africanus Fabius Q. f. Maximus Iullus Antonius M. f.

In high spirits, Augustus travelled back to Colonia Copia Felix Munatia in Tres Galliae, accompanied by Drusus and Tiberius.99 The steady stream of good news from around the empire encouraged the Senate to vote to consider closing the doors of the Temple of Ianus Quirinus, which had remained open since the last time they were shut in 25 BCE; but then Augustus received reports that ‘the Daci, crossing the Ister on the ice, carried off booty from Pannonia, and the Dalmatae rebelled against the exactions of tribute’.100 Tiberius immediately left to lead the campaign to quell the insurgents.101 The qualification that ‘wars had ceased’ was not, finally, met. The temple doors would have to stay open.

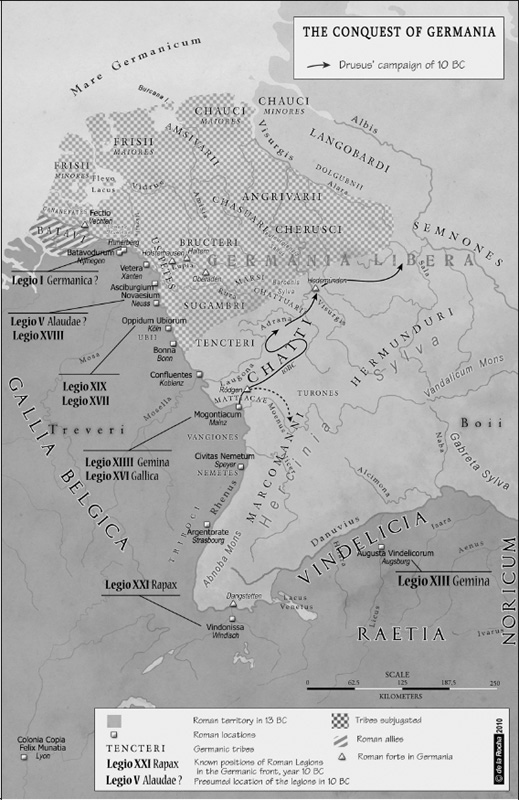

Drusus departed for Mogontiacum to continue his war in Germania. His objective this season was the subjugation of the Chatti (map 14).102 Dio reports that, in a volte-face to their position of the previous year, the Germanic nation had combined forces with the Sugambri. They lived in the area between Elder, Fulda and upper reaches of the Weser rivers in what is now Hessen on the edge of the Black Forest. It was a region notorious to the Romans for being inhabited by exotic, even mythical creatures.103 The Chatti had a reputation as formidable foot soldiers who, like the Romans themselves, were well organized, planned their actions strategically, fought in formations and erected camps while on campaign.104 They, and their neighbours the Tencteri, would now feel the cold, sharpened edges of Roman steel.105 Among important people (primores) fighting with the Romans over there were Avectius and Chumstinctus, both tribunes from the Belgic nation of the Nervii, about whose exploits nothing survives beyond a cryptic reference in the synopsis of Livy’s now lost books of Roman history.106

Map 14. Military operations in Germania Magna, 10 BCE.

On the battlefields of Germania, Drusus led from the front like the commanders of old. Inspired by the example of his distant ancestor M. Claudius Marcellus, he often charged the war chiefs opposing him at great personal risk to engage them in one-to-one combat in the hope of winning the spolia opima.107 The ambiguity of Suetonius’ language leaves open the possibility that he achieved the rare honour, last claimed by M. Licinius Crassus in 29 BCE.108

By the end of the campaign season, Drusus’ army had reached the northeastern corner of the territory of the Chatti. Some 240 kilometres (149 miles) away from Mogontiacum, on a bend in the Werra River at Hedemünden near Göttingen, he erected a new fort large enough for a single cohort.109 The archaeological site has produced a cornucopia of iron objects left by the troops based there, including hastaheads (spear-heads), ballista bolt-heads, dolabra (axes), nails, chains, hooks and even tent pegs with rings for tying leather straps to. The find of iron fetters betrays the presence of slavers: the P-shaped design of the restraint meant the prisoner had to keep his arms high across his chest where they could be seen, to avoid neck ache. These merchants in human lives (lixae) were making profits from the Roman army on active campaign.

From his base in Gallia Lugdunensis, Augustus eagerly awaited his stepson’s progress reports.110 In the summer, Drusus and Tiberius handed over their respective campaigns to their legati and returned to Colonia Copia Felix Munatia. On 1 August, the new cult complex to Roma et Augustus, begun two years before, was officially opened in the presence of the princeps himself.111 It marked an important stage in the transformation of the sixty conquered territories into three pacified provinces sharing a common future. Here the Concilium Galliarum would gather each year under the auspices of the tutelary goddess and its imperial patron, chaired by one of its own members as chief priest, and hold sacrifices at the great altar beneath columns topped with winged Victories and celebrate gladiatorial games at the adjacent amphitheatre – potent symbols of Roman culture combined by design to promote a burgeoning cult of victory.112 It was hoped that by bringing the people together, intertribal war could be avoided. It was an important milestone in the history of the lands conquered by Iulius Caesar four decades before, whose pacification was since made possible by his adopted son and heir.

North of the Danube River, bands of Daci under their king, Cotiso, raided unopposed into Roman-held territory. These fearsome warriors were notoriously difficult to beat.113 Nevertheless, ‘Caesar Augustus resolved to drive back this people.’114 He dispatched Cn. Cornelius Lentulus Augur, consul of 14 BCE and now Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore of Thracia Macedoniaque, to lead operations.115 Details of the Bellum Dacicum are sparse, but what survives hints at a hard-fought defensive war. The Roman force faced a motivated and numerically large opponent. Strabo reports that even in his day the Daci could field an army of 40,000 warriors.116 Florus writes:

Lentulus pushed them beyond the further bank of the river; and garrisons were posted on the nearer bank. On this occasion then Dacia was not subdued, but its inhabitants were moved on and reserved for future conquest.117

He also turned his attention to the neighbouring Sarmatae, who rode the Hungarian Plain unchecked and crossed the Danube at will on their horses. Lentulus’ mission was to prevent further incursions. It is not clear from Florus’ account that he succeeded here either, when he writes with contempt of the Sarmatae, ‘so barbarous are they that they do not even understand what peace is’.118

Leaving Colonia Copia Felix before the onset of winter, Augustus and his stepsons returned to Rome. For Drusus, what awaited him there was the turning point of his career.

Nero Claudius Ti. f. Drusus T. Quinctius T. f. Crispinus Sulpicianus

On 1 January, Nero Claudius Drusus, now in his 29th year, was sworn in as consul with his colleague T. Quinctius Crispinus.119 Over the last seven years he had proved the rightness of Augustus’ instinct that the young man had the natural courage and aptitude to be a fine field commander. Drusus was impatient to return to Germania, but before he could leave there was a formal matter to attend to in Rome. On 30 January – the birthday of his mother, Livia Drusilla – the Ara Pacis Augustae was finally ready for its official dedication.120

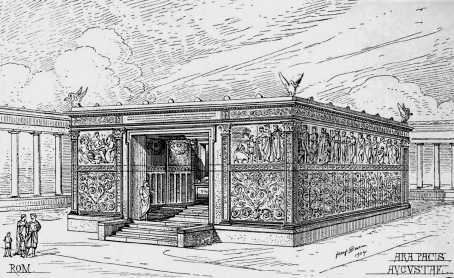

Some three-and-a-half years in the making, it was an expression in marble and paint of the aspiration of the age. It had been voted for by the Senate on the safe return of Augustus from his tours in the West in 13 BCE.121 Erected on the field of the war god, the altar to Peace was highly visible. Measuring 11.6 metres (38 feet) by 10.6 metres (35 feet), the re-assembled sacrificial altar stood on a raised podium within a sacred enclosure in the style of a templum, approached by ten steps on the west side (fig. 9). On the exterior wall of the enclosure, above a lower panel decorated with volutes of acanthus, a procession was depicted in halfrelief. The élite of Roman society are shown here: the Vestal Virgins, members of the religious colleges and their retinues of attendants, the consuls accompanied by their lictors carrying their fasces, and many other state officials. On the south side (plate 30), at the front of the procession was Augustus, shown as Pontifex Maximus. Further down the line stood a man, covered (velatus) with his toga. This was M. Agrippa.122 A boy in a tunic stood behind him clutching the edge of his toga while looking up at the lady behind – who may be Livia Drusilla.123 This boy may be C. Caesar or Lucius.124 The frieze on the north side showed the same procession but seen from the other side (plate 31). Among the people, Iulia was shown with a boy – perhaps L. Caesar.125 Augustus’ trusted deputies, Tiberius, Drusus, L. Domitius Ahenobarbus and Sex. Appuleius, were represented too. These men’s military victories were helping to establish the Pax Augusta.

Shortly after the ceremonials had concluded, and despite the occurrence of many ominous portents reportedly seen in Rome, Drusus set off again to lead the fourth year of the Bellum Germanicum.126 He launched the offensive from Mogontiacum (map 15). Crossing the Rhine, Drusus’ expeditionary force entered Germania through the lands of the Chatti, for the first time cutting a path through the Hercinia Sylva (Black Forest), fabled for its impassibility and bizarre flora and fauna.127 The army cut a pathway through and advanced swiftly northeast to engage the confederacy of the Suebi.128 Drusus met fierce resistance at every step, ‘conquering with difficulty the territory traversed and defeating the forces that attacked him only after considerable bloodshed’.129

Figure 9. The exquisite Ara Pacis was voted by the Senate in honour of Augustus. It was dedicated on 31 January 9 BCE, the birthday of Augustus’ wife, Livia.

The Roman invaders then entered the territory of the Cherusci, a nation of tough warriors, before reaching the Weser River. Marching further, the army eventually arrived at the west bank of the Elbe River.130 The Roman commander was eager to cross. He tried but, for reasons not explained in the surviving accounts, he failed in the attempt. It was late in the campaign season and he could not dawdle this far from the army’s winter camps on the Lippe and Rhine. While he decided what to do, he ordered his men to erect a victory trophy, ‘a high mound adorned with the spoils and decorations of the Marcomanni’.131 Known as the Tropaeum Drusi, it was the most northerly Roman-built structure up to that time; its map coordinates are recorded in Ptolemy’s Geography.132 Then a story began to circulate that Drusus had had a strange encounter:

For a woman of superhuman size met him and said: ‘Where, pray, are you hastening, insatiable Drusus? It is not fated that you shall look upon all these lands. But depart; for the end alike of your labours and of your life is already at hand.’133

As a chronicler, Dio was unwilling to discount the tale, but he remarked that Drusus departed with apparent haste from the region. On the march back there were other strange – some said supernatural – occurrences that unsettled the soldiers.134

Map 15. Military operations in Germania Magna, 9 BCE.

While riding on the return journey, Drusus fell – or was struck off – his horse which, in turn, fell upon him and broke his leg.135 The commander now mortally wounded, the army’s retreat was halted somewhere between the ‘Albis and Salas’ Rivers.136 A profound sense of gloom and foreboding settled over the already nervous troops. The marching camp they erected that night came to be called Castra Scelerata, the ‘Accursed Fort’.137 A messenger was immediately dispatched to inform Augustus. He had already moved to Ticinum (modern Ticino) in Gallia Cisalpina to be closer to the war zone and receive reports of progress. In the meantime, Tiberius had joined him from another tour of duty in Illyricum.138 Receiving the news of his brother’s fall, he raced to be with him, in so doing setting the land speed record of the ancient world.139 He arrived just in time to exchange some final words. After a fever lasting thirty days, Drusus died.140 Tiberius arranged for the body to be prepared for transportation. It was carried by the military tribunes and centurions on the first stage of the journey – the German nations even suspended hostilities to let them pass – as far as the army camp at Mogontiacum, and then conveyed by road to Italy.141 As the body approached each city, the leading men came out to take their turn to carry it.142 Each step of the way, Tiberius walked at the head of the column, an act regarded by Valerius Maximus as a supreme example of pietas, ‘devotion’.143

The cortège finally reached Rome in the winter. Received by the scribae quaestorii (the most important of the magistrates’ assistants), the body was laid in state.144 On the day of the funeral, the first eulogy was delivered by Tiberius in the Forum Romanum.145 The second was pronounced by his stepfather Augustus. Still holding legitimate imperium and technically at war, he was not permitted within the pomerium of the city so his funerary oration was delivered in the largest available building outside it, which was the Circus Flaminius.146 He is reported to have told the hushed audience that he ‘prayed the gods to make his Caesars [Caius and Lucius] like Drusus, and to grant him, when his time came, as glorious a death as they had given that hero’.147 The funeral bier was then carried upon the shoulders of men of the Ordo Equester to the Campus Martius.148 After the body was cremated, the ashes were placed in the Mausoleum of Augustus, alongside those of Marcellus, Agrippa and Octavia.149

It was a poignant way to end what had been a glorious five years of Augustus’ latest extended imperium. The Ara Pacis Augustae had been built as a symbol of the ending of wars in the West and the safe return of the man responsible for it. The future of the Tres Galliae now seemed secure. His great project to annex Germania, to which he had committed fully a third of his legions and several of which were presently stationed beyond the Rhine, was still unfinished – and now missing its field commander. The indispensable Agrippa, too, was gone. The timing could not be worse. On the night of 31 December, the power, which would permit the princeps to complete it, would expire.