Map 16. Haltern Roman Fort, Germany.

C. Marcius L. f. Censorinus C. Asinius C. f. Gallus

No longer imbued with war-making powers, Augustus was free once again to cross the pomerium and enter the city. Contrary to custom, he took the laurels from his fasces carried by his lictors into the Temple of Jupiter Feretrius as an offering.1 He was in a sombre mood and emotionally wrought. ‘He himself did not celebrate any festival in honour of the achievements,’ writes Dio, ‘feeling that he had lost far more in the death of Drusus than he had gained in his victories.’2 There were those – mostly opponents of the regime – who saw foul play at work in his stepson’s death. Drusus had been known to some for his outspoken view that his stepfather should relinquish his powers and let the Senate and People’s Assemblies rule unfettered, as they had in the old days.3 That opinion allegedly made him the object of suspicion by Augustus. Suetonius reports that there was a rumour that he had recalled Drusus from his province and, when he did not immediately obey the order, Augustus had him poisoned. The biographer himself doubted the truth of the allegation. Malicious chatter notwithstanding, Augustus’ personal feelings towards his stepson were well known. He had even announced in the Senate that he loved Drusus so dearly while he lived, he always named him joint-heir along with his sons, Caius and Lucius. In a moment of solitude, secreted away in the private office he called Syracusa on the top floor of his home, Augustus composed a laudatory inscription in verse which he placed on Drusus’ nîche in his Mausoleum, and began to write a prose memoir of the young man’s life.4

Separately, the Senate voted Nero Claudius Drusus (plate 29) several posthumous honours, including a marble arch adorned with trophies to straddle the Via Appia, and the honorific war title Germanicus which could be inherited by his descendants.5 His eldest son, Nero, shortly after adopted the title as his own praenomen.6 At the fortress of Mogontiacum on the Rhine, the men of the legions who had proudly served with Drusus raised their own tribute to his memory:

The army reared a monument in his honour, about which the soldiers should make a ceremonial run each year thereafter on a stated day, which the cities of Gallia were to observe with prayers and sacrifices.7

(The stone core of the cenotaph still stands in Mainz and is known as the Drususstein.)8

In this collective mood of reflection and introspection, the Senate willingly granted Augustus the imperium proconsulare for another five years.9 He accepted, ‘though with a show of reluctance’, since he often publicly expressed his intention to resign it.10 The urgent priority now was finishing the war in Germania. He dispatched his right-hand man Tiberius to complete the work begun by his brother.11 Paterculus writes of the 34-year-old commander that ‘he carried it on with his customary valour and good fortune’.12 Tiberius had matured into a formidable, but almost boorish, man with an intense personality and intimidating presence. He would stride with his head bent forward, wearing a stern expression on his face, and avoided conversation while walking; he displayed austere manners and had a preference for discipline that seemed better suited to the army camp than the dinner party.13 Augustus often tried to excuse his stepson’s mannerisms by declaring that they were natural failings, and not intentional, yet he was in no doubt of his abilities as a general.

Leaving with Tiberius was Augustus’ adopted son C. Caesar (plate 36) – just 14 years old – who would see the Roman army in action for the first time.14 Arriving in Germania, the nations of the Rhineland sought terms with Tiberius rather than go to war – all, that is, except the Sugambri.15 Augustus would not accept a truce with the Germans unless they were part of it. ‘To be sure, the Sugambri also sent envoys,’ explains Dio:

but so far were they from accomplishing anything that all of these envoys, who were both many and distinguished, perished into the bargain. For Augustus arrested them and placed them in various cities; and they, being greatly distressed at this, took their own lives. The Sugambri were thereupon quiet for a time, but later they amply requited the Romans for their calamity.16

Tiberius led his army across the country, crossed the Weser River, fighting battles and skirmishes with few casualties on his side, ‘for he made this one of his chief concerns’.17 The Sugambri then sought their revenge for past humiliations. They attacked the Romans, but in the engagement were decisively defeated. War chief Maelo surrendered unconditionally and Tiberius transplanted 40,000 prisoners from Germania, settling them in Belgica in the vicinity of Vetera on the Rhine.18 From that time large numbers of able warriors served in the Roman army with several Cohortes Sugambrorum, which would became known for their valour.19

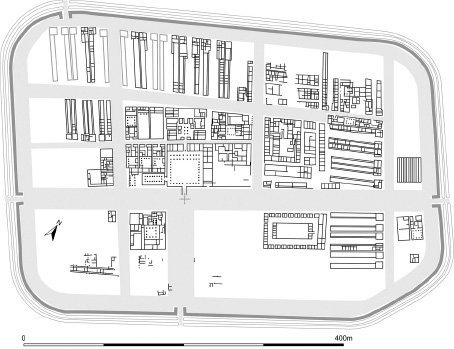

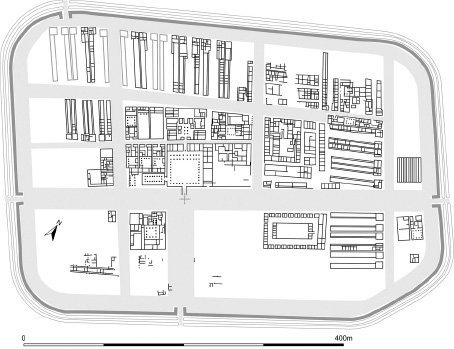

There are hints, too, that Tiberius used the year to consolidate the Romans’ gains in the region. The fortress at Oberaden on the Lippe River was abandoned and a new base was established further down river, about halfway to Vetera.20 It marked a more cautious strategy for Germania. Located at Haltern, the site had previously been occupied and the Annaberg may still have been operational at this time.21 Beside the river, a new legionary fortress was erected with a double ditch all around (map 16).22 Its principal interior buildings were eventually fabricated in wood.23 The Roman army intended to stay.

Map 16. Haltern Roman Fort, Germany.

Augustus was delighted with his stepson. He promoted Tiberius to commander of operations in Germania, permitted him to use the appellation imperator – though he did add one more acclamation to his own total – and approved him for a second triumph, opting not to celebrate it himself.24 Additionally, he arranged that Tiberius would be given one of the two consulships for the following year. Augustus also rewarded the troops with cash because C. Caesar had taken part in exercises with them (plate 38).25

C. Cilnius Maecenas, the cultured equestrian, died this year; he was in his late sixties. In concert with Agrippa, he had provided Augustus with valuable counsel over three decades and poets to sing the praises of the new age of glory and peace; he was also a calming influence in moments when the princeps raged out of control.26 On military and political affairs, the princeps would now have to rely more than ever on his other long-standing, but aging friend T. Statilius Taurus and the young, but promising, Tiberius.

Ti. Claudius Ti. f. Nero II Cn. Calpurnius Cn. f. Piso

On New Year’s Day, consul Tiberius and his colleague Cn. Calpurnius Piso convened the Senate in the Curia Octaviae, because it was located outside the pomerium.27 He announced that he would repair the Temple of Concord so that he could inscribe both his and his brother’s names on it, and then proceeded to celebrate his triumph.28 Afterwards he gave the customary banquet to the Senate at the Capitolium.

The consul might have hoped to serve out his term peaceably in Rome, but later in the year, when a messenger delivered the news that there was disturbance in Germania, he was obliged to take the field. The details of his manoeuvres are entirely lost. The historian Dio writes cryptically that ‘nothing worthy of mention happened in Germania’.29 Yet a passing tale preserved by Suetonius may relate to an event involving Tiberius during this year’s campaigning:

But in the very hour of victory he narrowly escaped assassination by one of the Bructeri, who got access to him among his attendants, but was detected through his nervousness; whereupon a confession of his intended crime was wrung from him by torture.30

At the end of the year, Rome’s riparian frontier in the north stretched from the English Channel, along the Rhine and Danube rivers to the Black Sea. After years of bitter fighting, the myriad nations of Germania, Illyricum and Thracia Macedoniaque were peaceful. Augustus could now make the case to close the doors of Ianus’ temple for the third time.31

D. Laelius D. f. Balbus C. Antistius C. f. Vetus

C. Antistius Vetus, the legatus who had faithfully served Augustus in the war against the Astures and Cantabri, was sworn in as consul.32 Many clamoured for Caius, the oldest son of Augustus, to be made consul too, but he – and his brother – were too young even to enroll in the army. It was a quandary for their adoptive father. Augustus was increasingly concerned about the boys. His heirs apparent were behaving like spoiled brats, not at all in the mould of their natural father M. Agrippa or the exemplum Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus.33

Augustus believed he could still rely on his stepson Tiberius. He was granted the tribunician power for five years, and assigned responsibility for Armenia.34 The frontier in the East was coming under pressure. The kingdom was slipping from under Roman influence since the death of Tigranes III and his succession by the pro-Parthian Tigranes IV; Augustus now sought to see Artavasdes III replace him.35 But the princeps was unprepared for his stepson’s reaction. Tiberius announced he was retiring from public life and sailed away to Rhodes as a private citizen, leaving his wife and retinue behind, taking only his astrologer Thrasyllus with him.36 Why he did so has perplexed historians, both ancient and modern, who have offered different explanations: he may have decided to remove himself so Caius and Lucius could grow into their roles out from under his shadow; or he was irked that the inexperienced but popular sons of Augustus were receiving all the attention; there were even rumours that the princeps had ordered him to leave. The true motive for his action remains a mystery. The stark reality for Augustus was that he now found himself without his right-hand man and completely reliant on his legati.37

One of these, C. Sentius Saturninus, having completed his tour in Syria, may have transferred this year to Tres Galliae and Germania as legatus Augusti pro praetore.38 In his new role he was placed ‘in charge of expeditions of a less dangerous character’ compared to the ones Tiberius undertook himself, writes Velleius, though he provides no specifics.39 The inference is that the army under Saturninus was engaged in routine policing duties, laying down the road network and town street plans that were essential to the pacification of a new province.40 He was ideally suited to the project, being not a warmonger but a man of purposeful action and foresight, equally comfortable in a combat role as he was in cultural pursuits.41 He was the friendly face of pacification.

In the southwest corner of the Alps on the Via Iulia Apta, which ran from Italy to Gallia Narbonensis, crossing the highest ridge of Mount Agel and following a natural depression some 500 metres up, a monument was nearing completion. It could be seen by anyone using the road, which ran along its west side. Within a temple-like precinct, the Tropaeum Alpium (at what is now La Turbie) stood nearly 50 metres (164 feet) high.42 It was Roman ‘wedding cake’ architecture at its finest. Upon a podium stood a rotunda of twenty-four Doric columns (plate 32), forming a colonnade around a core containing twelve nîches – perhaps for statues of gods or military commanders – topped by a cone-shaped roof, upon which stood a statue of Augustus. The view from this point looked far into Italy and beyond Antibes. In expertly carved lettering, originally gilded or painted, an inscription on the base read:

To Imperator Caesar Divi filius Augustus, Pontifex Maximus, acclaimed imperator fourteen times, in the seventeenth year of his holding the tribunician power, the Roman Senate and People, in remembrance that under his command and auspices all the Alpine nations, which extended from the Upper Sea to the Lower, were reduced to subjection by the Roman people. The Alpine nations so subdued were: Triumpilini, Camuni, Venostes, Vennonenses, Isarci, Breuni, Genaunes, Focunates, four nations of the Vindelici, Consuanetes, Rucinates, Licates, Catenates, Ambisontes, Rugusci, Suanetes, the Calucones, Brixentes, Lepontii, Uberi, Nantuates, Seduni, Varagri, Salassi, Acitavones, Medulli, Uceni, Caturiges, Brigiani, Sogiontii, Brodiontii, Nemaloni, Edenates, Esubiani, Veamini, Galliae, Triulatti, Ecdini, Vergunni, Eguituri, Nementuri, Oratelli, Nerusi, Velauni, and Suetri.43

It marked the end of the great effort expended by Roman armies over several decades to subjugate the forty-four nations who inhabited the Alps – a banner in gleaming white limestone (with architectural details popping out in colour) celebrating a ‘mission accomplished’.44 Completed between 1 July 7 BCE and 30 June 6 BCE, its dedication coincided with the creation of three new districts: Alpes Maritimae, Alpes Cottiae and Alpes Graiae. Thanks to Caesar Augustus, the Summa Alpe (Europe’s highest mountain range) was finally under the imperium of the Roman People. It would now be much harder for the pesky bandits who preyed on traders and officials to operate there.

| Imp. Caesar Divi f. Augustus XII | L. Cornelius P. f. Sulla | |

| suff. | L. Vinicius L. f. | |

| suff. | Q. Haterus | C. Sulpicius C. f. Galba |

The number of proconsuls and legati available to govern the provinces and command the legions was falling short of the ongoing need; consuls were encouraged to serve for a few months and then resign to make way for suffects.45 Augustus became consul for the twelfth time after an interval of eighteen years.46

With Tiberius in self-imposed exile, Augustus now needed to find ways to rapidly advance his two sons. It was an important time for C. Caesar. He came of age this year and his name and tribe were registered at the public records office. He was also appointed to a priesthood.47 As a special honour, Caius was appointed princeps iuventutis, ‘the first of the youth’, which gave him command of one of the six turmae of iuniores.48 Largely honorific, nevertheless it placed the young man in a position of having to manage a structured organization and observe its traditions. The role would require him to learn how to lead, master horsemanship and prepare his men for the transvectio equitum, the public paramilitary ceremony – revived by Augustus – held annually on 15 July of each year.49 Lucius, however, was still too young for a formal public role.

In Galatia-Pamphylia, the new Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore, P. Sulpicius Quirinius, assumed command. It was a troubled region. A coalition of bandits, called Homonadeis, were operating freely in Cilicia and challenging the internal security of the province.50 With Legiones V Macedonica and VII Macedonica, Quirinius set out to crush them. He besieged several of their strongholds, starved the inhabitants into submission and took 4,000 prisoners, whom he resettled in the neighbouring cities, leaving no one in the country who could take up arms against him while he was governor.51

Activities to pacify Germania continued apace. Haltern was now in operation as a permanent fortress, large enough for a single legion – most likely XIX – with an adjacent dock on the Lippe River to receive cargoes shipped from the bases on the Rhine.52

| C. Calvisius C. f. Sabinus | L. Passienus Rufus | |

| suff. | C. Caelius | Galus Sulpicius |

In March, King Herodes died in Jericho.53 In his last years he had suffered terribly with an affliction – possibly chronic kidney disease complicated by Fournier’s gangrene.54 He was buried in the Herodion, the hilltop fortress he had built for himself near Hierosolyma.55 His death marked the end of an era. In Herodes, Augustus had found a staunch ally, a true philo-Roman.56 His death created unwelcome uncertainty on Rome’s eastern frontier. Augustus discussed the succession with his friends and advisors, and approved the late king’s will and testament.57 It was decided that Herodes’ realm would remain an independent kingdom, but it would now be divided up among his sons. To Archelaos (Archelaus) as ethnarch (‘national leader’) was given Samaria and Iudaea; to Herodes Antipas as tetrarch went Galilee and the east bank of the Jordan; and to Philippos as tetrarch were assigned the Golan Heights in the northeast.

The transition of power between the heirs was not achieved peacefully, however. Archelaos, who arranged his father’s funeral, soon faced protests in the streets of Hierosolyma.58 The new king tried using persuasion on the crowds, but when his commander entered the Temple compound he was pelted with stones even before he could speak to the protesters. Subsequent attempts at mediation also failed. By the time of Passover – the seven days of the ‘Feast of Unleavened Bread’ on the fifteenth day of the month of Nisan – their number had grown considerably. Archelaos was worried by the developing situation:

and privately sent a tribune, with his cohort of soldiers, upon them, before the disease should spread over the whole multitude, and gave orders that they should constrain those that began the tumult, by force, to be quiet. At these the whole multitude were irritated, and threw stones at many of the soldiers, and killed them; but the tribune fled, wounded, and had much ado to escape so. After which they betook themselves to their sacrifices, as if they had done no mischief; nor did it appear to Archelaos that the multitude could be restrained without bloodshed.59

The protests reached a new level of violence,

so he sent his whole army upon them, the infantry in great multitudes, by the way of the city, and the cavalry by the way of the plain, who, falling upon them on the sudden, as they were offering their sacrifices, destroyed about 3,000 of them; but the rest of the multitude were dispersed upon the adjoining mountains: these were followed by Archelaos’s heralds, who commanded everyone to retire to their own homes, whither they all went, and left the festival.60

The king urgently needed help to contain the sedition. There were three legions in neighbouring Syria under the command of P. Quinctilius Varus. Having completed a successful term as proconsul of Africa between 8 and 7 BCE, Augustus had appointed him to replace Sentius Saturninus as legatus Augusti pro praetore.61 Varus received the king’s formal request for assistance and proceeded to Caesarea Maritimae, the great port city built by the late Herodes on the Mediterranean coast, taking one legion with him.62 The procurator of Syria, a certain Sabinus, had already arrived. He intended to go to Iudaea to secure the cash and valuables of the late King Herodes’ estate that had been bequeathed to the Romans and which, as the official responsible for collecting taxes and duties, was his responsibility. He was instructed by Varus to remain there. In the meantime, Sabinus met Archelaos and his entourage at the port before the royal party departed for Rome.

With the king out of the way, Varus now marched on Hierosolyma with his army to quash the forces of revolt.63 Having entered the city and taken the royal palace, he stationed his legion there to secure it. With order restored, Varus then left for Antiocheia.64 The heavy-handed actions of the procurator following the legate’s departure, however, incited yet more trouble. Keen to complete his mission, Sabinus used men of Varus’ legion in the city and his own armed guards to attempt to force open the various strongholds at which the nation’s wealth was kept and to take it. Incensed by the provocations, crowds came down from Galilee, Idumaea, Jericho and Perea to join the people of Hierosolyma, and settled in three large camps outside the city. The Romans now found themselves besieged by angry protesters. Unable to deal with the rapidly deteriorating situation, Sabinus dispatched a courier to Varus with a message to come urgently to his aid. Josephus describes the scene:

As for Sabinus himself, he got up to the highest tower of the fortress, which was called Phasaelus (it is of the same name with Herodes’ brother, who was destroyed by the Parthians) and then he made signs to the soldiers of that legion to attack the enemy; for his astonishment was so great, that he dared not go down to his own men. Hereupon the soldiers were prevailed upon, and leaped out into the temple, and fought a terrible battle with the Jews; in which, while there were none over their heads to distress them, they were too hard for them, by their skill, and the others’ want of skill, in war; but when once many of the Jews had reached the top of the cloisters, and threw their darts downwards, upon the heads of the Romans, there were a great many of them destroyed. Nor was it easy to avenge themselves upon those that threw their weapons from on high, nor was it more easy for them to sustain those who came to fight them hand to hand.65

In the general confusion, several buildings, including ones around the Temple with their fabulous contents, were set alight. Trapped inside, some soldiers and rebels burned to death.66 Nevertheless, Sabinus found the treasure he was so determined to take.

Among the rebels were men of Archelaos’ own army, but the toughest of them were the 3,000 from Sebastia who remained on the side of their Roman ally and were present at Hierosolyma.67 Commanding the infantry was a man named Gratus, while in charge of the cavalry was another called Rufus. Their loyalty and troop numbers tipped the balance in favour of the defenders. The besiegers, whose progress now slowed, changed tack and tried to negotiate with the Romans. They proposed to let Sabinus go if he would leave the city and take the legion with him. The procurator did not trust the Jewish emissaries, however, and refused to leave, preferring to hold out until Varus arrived with soldiers.

The turmoil in Hierosolyma created a window of opportunity for other troublemakers to promote their own agendas. In Idumaea, some 2,000 veterans of Herodes’ army re-formed and mounted attacks against men of Archelaos’ army.68 In Galilee, at Sepphoris, writes Josephus:

There was one Iudas (the son of that arch-robber Hezekias, who formerly overran the country, and had been subdued by King Herodes); this man got no small multitude together, and broke open the place where the royal armour was stored, and armed those about him, and attacked those that were so earnest to gain the dominion. 69

In Perea, one of the king’s own servants, Simon, staked his own claim to the kingdom.70 Described as a tall and handsome man, he broke into the palace at Jericho with a gang of armed men and stole its contents before setting the building on fire. The rebels would have succeeded in spreading the chaos wider had not Gratus arrived with archers from Trachonitis. The usurper Simon tried to escape through a narrow pass, but pursued by Gratus and his mounted contingents he was intercepted. With a swipe of his sword, Gratus slashed Simon’s neck and killed him.

In Emmaeus, a shepherd named Athrongeos claimed to be a king.71 Reportedly a strong, fearless man, he appointed his four brothers to be generals and commanders with him. Together they gathered armed men and overran the country:

killing both the Romans and those of the king’s party; nor did any Jew escape him, if any gain could accrue to him thereby. He once ventured to encompass a whole troop of Romans at Emmaus, who were carrying corn and weapons to their legion; his men therefore shot their arrows and darts, and thereby slew their centurion Arius, and forty of the stoutest of his men, while the rest of them, who were in danger of the same fate, upon the coming of Gratus, with those of Sebastia, to their assistance, escaped. And when these men had thus served both their own countrymen and foreigners, and that through this whole war, three of them were, after some time, subdued; the eldest by Archelaos, the two next by falling into the hands of Gratus and Ptolemaios.72

Receiving Sabinus’ message, Varus commanded his two other legions with four alae of horse to march south to Ptolemais.73 He issued orders for the auxiliaries sent by the allied kings and city governors to meet him there. As he passed through the colonia of Berytus, 1,500 legionary veterans volunteered to join him. Arriving at Ptolemais, where he found Aretas the Arabian (who had brought with him a large number of infantry and cavalry), Varus split his army into two groups. The first he placed under the command of his friend Caius (whose nomen genticulum is not recorded) and dispatched him to Galilee. Caius defeated all those whom he encountered and captured the city of Sepphoris, razed it and enslaved its inhabitants. Varus himself led the second army group. He marched to Samaria where, because he learned that the city had not participated in the troubles, he left it unharmed, and pitched his camp instead at a nearby village called Aras. He then marched on to the village of Sampho, another fortified place, which was plundered for its treasures and set alight by the Arabian allies. When its inhabitants evacuated their town, Emmaus was also burnt on the orders of Varus.

The hinterland quelled, Varus could turn his attention to Hierosolyma itself, which was still under siege.74 When he was spied on the horizon leading his army, the protesters outside the city abandoned their camps and quickly dispersed. The citizens who had been trapped inside the walls came out and warmly welcomed the legatus Augusti. He was met by a number of officials, among them Joseph (the first cousin of Archelaos), Gratus and Rufus, and the men of the legion who had stood firm during the unrest. As for Sabinus, afraid to present himself to Varus, he had already slipped away to Caesarea. Now in control of the city, the Roman commander ordered mopping up operations:

Varus sent a part of his army into the country, against those that had been the authors of this commotion, and as they caught great numbers of them, those that appeared to have been the least concerned in these tumults he put into custody, but such as were the most guilty he crucified; these were in number about 2,000.75

Varus was informed that there were still 10,000 men at arms in Idumea.76 He also learned that the Arabian troops did not act like regular auxiliaries in the field and were engaged in a private war of retribution borne of their deep hatred of Herodes, and were laying waste to the country. The Roman commander immediately ordered them to withdraw, deploying his own soldiers instead to carry out the mission to seek out and destroy the remaining rebels. Heeding the advice of Achiabus (Herodes’ first cousin), many insurgents surrendered themselves to the Romans. Varus showed them clemency, forgiving the majority for their offences, but arrested their commanders and sent them to Augustus to be examined by him in person. (The princeps would later forgive all, except the king’s relations who had engaged in a war against a king of their own family and had them executed.) Satisfied that he had settled matters at Hierosolyma, Varus left the single legion he had originally assigned to it as a permanent garrison and returned to Antiocheia on the Orontes with the rest of the army.

In Germania, the process of pacification continued apace. This year trees were felled to produce the timber used in the construction of buildings being erected in a new town at Waldgirmes.77 Located on a spur of land along the Lahn River, the settlement or entrepôt featured a forum with basilica and at least twenty-four houses or shops. Here Roman and German merchants peaceably traded goods together within a secure area bounded by a double ditch and palisade. Gateways on three sides and a watchtower on the fourth imply the presence of a military guard detail in case of trouble.

L. Cornelius L. f. Lentulus M. Valerius M. f. Messalla Massallinus

L. Cornelius Lentulus and M. Valerius Messalla Messallinus were sworn in as consules ordinarii for the year.78 Lentulus served the full year and drew the lot in the autumn that won him the proconsulship of Africa the following year.79 Messallinus, son of the Messalla Corvinus famed for his oratorical skills, had done nothing in his military career that merited recording by the historians and, indeed, he may have advanced through the cursus honorum with help from his esteemed father. He was known personally to Augustus, having been a member of the collegium of the quindecimviri sacris faciundis responsible for the Sybilline Books since 21 BCE, and had attended the Ludi Saeculares in 17 BCE. 80 With mentoring, the 40-year old could yet prove his worth as a commander in the field.

Agrippa Postumus was now old enough to be enrolled among the young men of military age.81 Strangely, he was not accorded the same honours as his older brothers.82

No record of any wars fought this year survives.83

| Imp. Caesar Divi f. Augustus XIII | M. Plautius M. f. Silvanus | |

| suff. | L. Caninius L. f. Gallus | |

| suff. | C. Fufius Geminus | |

| suff. | Q. Fabricius |

There was more churn in the consulships to create more ex-consuls for provincial, legionary and other leadership appointments. Augustus, now a man of 60 years of age, started the year as consul for the thirteenth time.84 He yielded it to C. Fufius Geminus, who in turn resigned after a few months in office to be replaced by Q. Fabricius. Augustus’ colleague was novus homo M. Plautius Silvanus, who resigned in favour of L. Caninius Gallus. Among this group, after Augustus only Gallus had earned military distinction, having ‘conquered the Sarmatae . . . and driven them back across the Ister’ in 17/16 BCE.85 As one of the three commissioners responsible for the mint in Rome in 12 BCE, he had ensured that Augustus’ successes in Germania were promoted on the coinage.86

Apparently unprompted, the Popular Assembly unanimously voted Augustus an accolade.87 On 5 February, now ex-consul Valerius Messalla Messallinus spoke in the Senate proposing the same motion, which is recorded verbatim by Suetonius:

‘Good fortune and divine favour attend you and your house, Caesar Augustus; for thus we feel that we are praying for lasting prosperity for our country and happiness for our city. The Senate in accord with the People of Rome hails you ‘‘Father of the Fatherland’’.’ Then Augustus, with tears in his eyes, replied as follows (and I have given his exact words, as I did those of Messalla): ‘Having attained my highest hopes, Conscript Fathers, what more have I to ask of the immortal gods than that I may retain this same unanimous approval of yours to the very end of my life?’88

The title Pater Patriae had been granted to only a few other men in Rome’s past, but most significantly to its legendary founder Romulus.89 It was the honour Augustus was most proud of.

L. Caesar was now in his fifteenth year. On 17 March, he put away the bulla of his boyhood and donned the toga virilis. He would now be eligible to begin his public career. He received the honours that had been granted to his popular older brother, including the post of princeps iuventutis.90 Unlike Caius, however, he was appointed as augur, an ancient priesthood that interpreted the god’s opinions by studying the behaviour of birds.91 With his older sibling, Lucius organized this year’s Lusus Troiae.92 Their youngest brother M. Agrippa (Postumus), now aged 10, would join them and perform mock military exercises in this, his first Circensian Games.93

On 12 May occurred the long-awaited dedication of the Forum Augustum.94 Almost two decades in the making, it was a meeting place fit for the people of a world power. Rectangular in shape, measuring about 125 metres (410 feet) long and 90 metres (295 feet) wide, it featured the innovation of two large semicircular apses – one on each of the southeast and northwest sides and one at the northeast end – to provide additional space (map 17).95 The precinct was surrounded by a wall. At the northeastern end it stood nearly 36 metres (118 feet) high and was constructed of peperino (a light, porous volcanic rock) to protect it against fire – a regular occurrence in Rome – and to block out the view behind of the neighbourhood, which was comprised of ugly low-grade residential buildings. Directly in front of it stood the Italic-style podium temple to the god of war and vengeance, Marti Ultori, vowed by Imp. Caesar Divi filius at the Battle of Philippi forty years before (fig. 10).96 Financed through funds raised from sales of spoils from the war in Egypt, Germania, Hispania and Illyricum, there had been unforeseen architectural and construction delays; even though the temple was still not finished Augustus insisted the forum be officially opened.97 The final touches could wait. The central figure of its pediment – supported by columns topped with Corinthian capitals – Mars the Avenger, flanked by other gods and goddesses, with Aeneas carrying his father in the lower left corner and Romulus bearing a trophy in the lower right.98 In front of the temple on a plinth was mounted a quadriga driven by Augustus (dedicated by the Senate to him).99

Map 17. Ground plan of the Forum Augustum.

Figure 10. The Temple of Mars Avenger (Templum Marti Ultori) was the centrepiece of the Forum Augustum in Rome. The military ensigns recovered from Parthia were kept here along with the sword of Iulius Caesar.

The complex itself was an architectural wonder – state of the art for the time – incorporating many varieties and colours of marbles for the pavements, columns and statues (plate 35). Pliny the Elder considered the Forum Augustum to be one of the most beautiful buildings in Rome in his day.100 The edifice formed a backdrop for other decorations weighty with meaning and significance.101 Many fine art works were displayed in it, among which were two large paintings of Alexander the Great by the celebrated Apelles, inviting comparison with the Roman sponsor of the new Forum.102 Covered porticos of thirty columns each lined the two longest sides of the Forum, forming a Roman ‘Hall of Fame’. Erected along them were bronze statues of summi viri (‘topmost men’), and all the viri triumphatores (‘men of triumph’), from the legendary founder Aeneas and Romulus to Augustus’ time, chosen either for their civic or military virtues.103 The name and career history (titulus) of each was engraved on the plinth and a description of his achievements (elogium) carved on a marble slab was fixed to the wall below.104

On this spring day, the inauguration of the Forum was accompanied by great ceremonial. Augustus and his two adopted sons proudly led it. Both young men had been granted the right to consecrate the Temple of Mars Ultor ‘and all such buildings’ for this purpose.105 As the new princeps iuventutis (plate 37), Lucius and his turma – bearing spears and shields – presented a mounted pageant before the assembled array of aquilae and signa cohortis which had been brought down from their temporary home.106 Joined now by his older brother, Caius, and father Augustus, the family observed a lustration with sacrifices at the altar in the precinct to consecrate and cleanse it. The suovetaurilia involved the sacrifice of a pig (sus), a sheep (ovis) and a bull (taurus) with a ritual incantation to Mars pater.107 The litany having been delivered perfectly word-for-word and the omens having been declared favourable, the dignitaries may then have accompanied the military standards as they were carried in solemn procession to their new home within the temple, where the sword of the avenged Iulius Caesar was also to be displayed.108 They were placed before the giant statues of Mars (plate 34), Divus Iulius and Venus, which stood in an apse inside the sacred space, their polished metal surfaces reflecting the flickering flames and bathed in the hues of glowing embers from the tripods that illuminated the interior of the building.

Once the formal opening ceremony was concluded, the crowds were treated to entertainments in the Circus Flaminius. There was a beast hunt that saw 260 lions slaughtered, and later in the programme the arena was flooded to create an environment in which thirty-six crocodiles could be slain.109 Particularly memorable was ‘the magnificent spectacle of a gladiatorial show [in the Saepta] and a mock naval battle’ between combatants representing the Persians and the Athenians.110 The choice of opposing sides was deliberate. The struggle between East and West continued to excite the Roman imagination. It was a reminder, too, that the non-aggression pact between Parthia and Rome was agreed under Augustus’ auspices. (Faithful to historical events, the Athenians won).111 Anticipating the popularity of these spectacles, Augustus stationed guards of the Cohortes Urbanae across the city to deter any robbers who might be tempted to break into the houses left unattended by their owners who were away at the games.112

The end of the momentous day marked the time for Caius to depart for his new assignment.113 Now aged 17, he was old enough to see active service in the field. Initially he would serve with the legions on the Danube.114 But if his father thought the placement on the front line would improve his command skills and toughen his spirit through exposure to army life, he was to be disappointed. Dio remarks that Caius fought no battles himself, not because there was no military action, but rather he was learning to command from behind in quiet and safety by delegating to others the dangerous undertakings. 115

In Rome, Augustus made yet more adjustments to the military. In a significant change to the command structure of his own guard unit, he appointed two praefecti to command the Cohortes Praetoriae.116 To the positions he appointed men of the equestrian order, known to be Q. Ostorius Scapula and P. Salvius Aper. Up to then, each of the nine cohortes of up to 1,000 men apiece had had its own tribunus. Augustus still allowed no more than three cohorts to be billeted in Rome – and even then they were scattered throughout the city – at any one time, the rest being stationed around Italy.117 Ever mindful of costs, Augustus struggled with the expense of keeping the field army.118 He introduced a bill in the Senate proposing that a budget of sufficient amount, rolling from year to year, should be created, in order that the soldiers would be assured of receiving their pay and bonuses without the need to raise additional monies from other sources. The means for setting up such a fund were urgently sought.

| Cossus Cornelius Cn. f. Lentulus | L. Calpurnius Cn. f. Piso (Augur) | |

| suff. | A. Plautius | A. Caecina (Severus) |

Taking the oath on 1 January to faithfully serve the Res Publica as its consuls were Cossus Cornelius Lentulus and L. Calpurnius Piso. They would each step down to allow two novi homines, respectively A. Plautius, son of the praetor urbanus of 51 BCE, and A. Caecina Severus, to serve in high office.

Reports reached Augustus that the pro-Roman Artavasdes III had been deposed as king of Armenia and that the Parthians were supporting the rebels. 119 The apparent abandonment of their alliance with Rome meant that the peace along the eastern frontier, which had held for a generation and counted as one of Augustus’ singular achievements, was now seriously at risk. He needed to ensure the kingdom stayed within the Roman sphere of influence as a buffer against Parthia’s territorial ambitions. He felt he was too old to take the field himself: someone else would have to go and lead the Roman response if it came to war. Tiberius was unavailable. While Augustus could have chosen from among his best legati, he decided, instead, to appoint his own son C. Caesar to the combat leadership role.120 Sending him would impress upon the Parthian king the gravity with which he viewed the infringement. The 19-year-old was given the special assignment as Orienti praepositus (‘overseer of the East’), and to ensure he had the legal power to wage war in Augustus’ name, Caius was voted the imperium proconsulare which had been forfeited by Tiberius.121 He was also made consul designate for the following year. It was an extraordinarily fast career advancement for the young man.

Compensating for his inexperience in military and political affairs, Augustus assigned his son the services of an advisory body formed of official ‘advisors and guides’.122 Chief among them was M. Lollius, the former governor of Galatia and Macedonia, and the same man who had been responsible for the eponymous disaster in Gaul in 17 BCE.123 The other notable was P. Sulpicius Quirinius, the ex-consul who had distinguished himself in wars in Cyrenaica and Cilicia. Also travelling with them were M. Velleius Paterculus, the historian who was then a serving tribunus militum, and L. Aelius Seianus, son of the Praefectus Praetorio who likely marched with the one, or more likely two, Praetorian Cohorts that would guard the princeps’ son for the duration of the assignment.124 While in Syria, Caius could also draw upon the expertise and local knowledge of the legati of the legions and praefecti of the auxiliary units stationed in the province. Caius left Rome on 29 January. Travelling by ship, he stopped at several ports on the outbound journey before reaching Syria.125

In the western Balkans, L. Domitius Ahenobarbus (cos. 16 BCE) was now Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore of Illyricum.126 While active along the Danube, he intercepted the Hermunduri nation, which had migrated from its homeland in search of a new place to live.127 Ahenobarbus found them land in the territory of the Marcomanni, who had since migrated to Bohaemium (modern Czech Republic). Once satisfied they would remain there, he proceeded north and crossed the Elbe River, achieving what Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus had not.128 He encountered no resistance from the local people – indeed, he even established friendly relations with them.129 To mark his achievement, he set up an altar to Augustus on the bank of the river.130

| C. Caesar Aug. f. | L. Aemilius Paulli f. Paullus | |

| suff. | M. Herennius M. f. Picens |

Despite being thirteen years younger than was required, C. Caesar was elected as consul.131 There was a practical reason for his promotion. As consul, his stature was greatly enhanced as a negotiator with the Parthians. The young man received the confirmation while at his field headquarters in Syria.132 His colleague back in Rome was L. Aemilius Paulus, one of whose ancestors stood with the famous Scipiones against Hannibal Barca of Carthage.133

Learning that Caius was in the border region, a diplomatic spat ensued between Augustus and Frahâtak V.134 The Parthian king sent envoys to Rome with a message politely, but firmly, requiring the return of his brothers as a prerequisite for a peace settlement. Dio explains that Augustus sent him a reply, addressing the recipient simply as ‘Phrataces’, purposely omitting the royal title of ‘king’. In the letter he required the Parthian to lay aside the royal name and to withdraw from Armenia. Frahâtak wrote back in a generally supercilious tone, addressing Augustus simply as ‘Caesar’ and calling himself ‘King of Kings’. Tigranes, who was the hostage of Augustus, refrained from sending any envoys. However, when the pro-Parthian king Artabazus fell ill and died, which meant his rival had been removed, Tigranes sent gifts to Augustus and petitioned him for the kingship of Armenia. Influenced by these considerations, and at the same time fearing a war with the Parthians, Augustus accepted the gifts and released him with high hopes to Caius in Syria.

The presence of Augustus’ own son so close to the international frontier had the desired effect on the Parthians. Frahâtak V, the son of King Frahâta (Phraates) III from whom, eighteen years earlier, Tiberius had received back the signa, sought to de-escalate the spiraling diplomatic crisis by withdrawing his troops from Armenia.135 A summit conference was held to craft a new treaty between the two superpowers. Velleius Paterculus witnessed the event himself and writes:

On an island in the Euphrates, with an equal retinue on each side, Caius had a meeting with the king of the Parthians, a young man of distinguished presence. This spectacle of the Roman army arrayed on one side, the Parthian on the other, while these two eminent leaders not only of the empires they represented but also of mankind thus met in conference – truly a notable and a memorable sight.136

The Parthians agreed to renounce their claim on Armenia on the condition that the king’s brothers – his four sons – remained outside his realm.137

Either during the dinner before the talks were scheduled to take place, or following the formal negotiations, Frahâtak revealed that Lollius had been taking bribes from the Parthians, which was consistent with his reputation for avarice and underhandedness.138 It was a deeply embarrassing admission. Here was evidence from the highest level source that one of Augustus’ trusted deputies was working as a double agent. He was promptly recalled to Rome to face charges. Rather than suffer the humiliation of a trial and almost certain exile, or possibly worse, Lollius took his own life. Caius immediately replaced him with P. Sulpicius Quirinius, whose loyalty was unimpeachable.139

C. Caesar’s letter announcing the news of the new pact with Parthia was read out in the Senate by Lucius, a task he always enjoyed.140 It was likely for this achievement – a victory over Parthia without shedding Roman blood – that Augustus received his fifteenth acclamation.141

Then came a dramatic and unforeseen setback. Tigranes was struck and killed by unnamed ‘barbarians’.142 As an ally under treaty, the Romans were obliged to respond. The inexperienced young Caius suddenly and unexpectedly found himself having to deal with an international crisis.143

Elsewhere in the Roman world there were military adventures. L. Caesar was preparing to embark on his trip to Hispania Taraconnensis to be trained for the first time with the legions.144 In one of the provinces of North Africa (presumed to be Cyrenaica), there were raids by bandits or a military invasion.145 The anticipated violence of the ensuing Marmaric War appears to have been sufficiently intense that soldiers had to be called in from neighbouring Egypt to supplement the local force. The arrival of an unnamed tribune from a Cohors Praetoria – perhaps one accompanying L. Caesar – marked the turning point in the struggle to regain control.146 The anonymous tribunus militum was so successful in leading the troops to expel the enemy that no senator governed the cities in the Roman province for several months.

Senator Domitius Ahenobarbus had since transferred from a successful tour in Illyricum to Germania as legatus Augusti pro praetore.147 The new governor inherited a province that had remained largely trouble-free since Tiberius’ punitive expeditions, and he could pursue policies and activities consistent with pacification. One of his first decisions was to move the provincial capital from the army base at Vetera to the civilian settlement at Oppidum Ubiorum on the Rhine, where an altar to the cult of Augustus was being erected and on account of which it became known as Ara Ubiorum.148 In the west of the province, he constructed a corduroy road of wooden planks laid over marshland in the country of the Cherusci called the Pontes Longi (‘Long Bridges’).149 That Ahenobarbus tried to secure the return of certain exiles of the Cherusci nation through intermediaries, but had failed in the attempt, is revealed by Dio.150 The negotiations may not have been helped by his reputation for haughtiness, extravagance and cruelty, or his complete disdain for social rank and good manners.151 An unintended consequence of this diplomatic defeat was that the other Germanic nations, who took it as a sign of Roman weakness, apparently now felt contempt for them too.152 The ‘barbarians’ had proved that the Romans were not, after all, invincible.

| P. Vinicius M. f. | P. Alfenus P. f. Varus | |

| suff. | P. Cornelius Cn. f. (Lentulus) | T. Quinctius T. f. Crispinus |

| Scipio | Valerianus |

In the East, Ariobarzanes II prepared himself to be crowned king of Armenia, but while he was the choice of the Romans his subjects-to-be felt very differently.153 The Armenian people rose up in protest at the imposition of a man they did not want as their ruler, perhaps incited to do so by the Parthian king.154 C. Caesar was now obliged to enter Armenia with his army and come to Ariobarzanes’ assistance, a situation which could yet escalate into a full-blooded war with Parthia.155

Shortly before 1 July, having been away for eight years, Tiberius returned to Rome; he was still a private citizen.156 Why he chose that moment to return is unclear. In his account, Dio ascribes the change of heart to Tiberius’ interest in astrology, through which he had foreknowledge of the fates of Augustus’ sons, while Suetonius mentions C. Caesar’s association with the disgraced M. Lollius (the princeps’ own appointee) as being a clear factor in his favour.157 Tiberius could be strong willed, but never a traitor. The intervention of his mother, Livia, may also have played a role.158

On 20 August, L. Caesar, while on his way to begin his military service in the Hispaniae, died at Massilia (modern Marseille).159 His was not a heroic death; the cause is simply described as ‘a sudden illness’.160 He may have contracted an infection on one of the missions to many places Dio alludes to.161 His body was prepared for transportation by sea to the port at Ostia, where it was received by military tribunes and thence conveyed to Rome.162 A state funeral was held for the youngest of Augustus’ adopted sons, whose ashes were placed in his mausoleum.163

As Tiberius had done with the Sugambri in 8 BCE, the praetorian-grade proconsul of Macedonia, Sex. Aelius Catus, oversaw the transplantation of some 50,000 Getae across the Danube River.164 They were granted land in Thracia, with whose inhabitants they shared a common language. In time this community would come to be called Moesia.

At the end of another five-year period, the primary task of the princeps in his province was still incomplete. Under his auspices, Roman armies had largely been successful in maintaining the security of the empire from threats, both from within and without, even at the cost of the life of his stepson. While the pacification of Germania was progressing and order had been restored to Cilicia and Iudaea, on the eastern edge of the empire Armenia was in revolt and there was now the real possibility of an all-out war with Rome’s longstanding rival. Though in mourning for the death of his adopted son, Augustus was the only man with the ability and experience of managing the military resources needed to ensure the integrity of Rome’s borders, but his legal power to do so was due to end.