Map 18. Anreppen Roman Fort, Germany.

| L. Aelius L. f. Lamia | M. Servilius M. f. | |

| suff. | P. Silius P. f. | L. Volusius L. f. Saturninus |

The Senate renewed Augustus’ proconsular command powers for another ten years.1 Dio remarks that he accepted this, his fourth ten-year term, under compulsion. He had mellowed with age – he would be 66 at his next birthday in September – and acted largely out of concern to retain the goodwill of the Senate. Weighing on his mind, however, was the proxy war with Parthia. He waited eagerly for news from the eastern front, where C. Caesar was now engaged in full combat operations in Armenia.2 The expeditionary force had taken up a position at the strategically important fortress city of Artagira (or Artageira).3 It was one of several fortified sites around the country at which the royal treasure of Tigranes II and Artavasdes of the Artaxiad dynasty had been hidden.4

There are several versions of the events.5 In the account of Strabo, who wrote closest to the time of the events, a governor named Adon (or Addon), who had been appointed by the ousted Armenian king, is responsible for defending the stronghold.6 Adon proves loyal to the old king and will not yield Artagira to the Romans. Caius then lays siege to the walled fortress. In Dio’s version of the story, written almost two centuries after the war, Adon lures Caius into approaching the city’s walls on the pretence he will reveal to him the Parthian king’s secrets – presumably of the whereabouts of the king’s valuables – but double-crosses the Roman and succeeds in wounding him.7 The Roman army then besieges Artagira. In his account of the Bellum Armeniacum, Florus introduces another character:

For Donnes, whom the king had appointed governor of Artagera, pretending to betray his master, attacked the [Roman] commander while he was examining a document, which he had himself handed to him as containing a list of the treasures, and suddenly struck him with his drawn sword. Caesar recovered from the wound for the time being . . . His barbarian assailant, beset on all sides by the angry soldiers, made atonement to the still surviving Caesar; for he fell by the sword, and was burnt upon the pyre on which he hurled himself after he was stabbed.8

In Rufus Festius’ even later telling, this same Donnes is described as having been appointed by King Arsaces as the commander of all forces in Parthia.9 They may all contain elements of truth.

After a long siege, the Romans finally stormed the fortress, captured its commandant and pulled down its walls.10 The soldiers hailed both Augustus and Caius as imperator.11 The rebellion having been crushed, the pro-Roman Ariobarzanes II of the Arsacid dynasty was finally enthroned as king of Armenia.12 When he unexpectedly died shortly after, he was succeeded by Artabazus, another Arsacid, with Augustus’ full blessing.

The young Roman commander was, however, wounded. The Fasti Cuprenses, a Latin inscription found at Cupra Marittima listing Roman consuls, gives the authorized, matter-of-fact version. It states:

C. Caesar, son of Augustus . . . on 9 September was struck down waging war in Armenia against the enemies of the Roman People while he was besieging Artagira, a town of Armenia.13

He was not dead, but he was badly injured and his wound caused him to fall seriously sick.14 He would not have lacked for medical care. As a member of the princeps’ family, he would have had a personal physician, but he could also call on the services of the professional medici of the legions who were skilled in treating combat traumas of many kinds.15 However, Dio notes that Caius’ health was not known for being particularly robust and the ensuing fever clouded his normally clear thinking.16 In this unsettled frame of mind, Caius wrote to his father pleading to be relieved of his duties and to be allowed to retire as a private citizen. Augustus reluctantly agreed to his request on the condition that he should immediately return to Italy. Perhaps the young man was delirious; some rest and recuperation might restore his faculties, he thought. The injured commander made his preparations to leave. With winter approaching, Quirinius supervised the withdrawal of Roman troops from Armenia; he was temporarily appointed Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore of Syria until his official replacement, L. Volusius Saturninus (suff. 12 BCE), arrived.17

| Sex. Aelius Q. f. Catus | C. Sentius C. f. Saturninus | |

| suff. | Cn. Sentius C. f. Saturninus | C. Clodius C. f. Licinius |

In the new year, his condition worsening, C. Caesar boarded a merchant ship bound for Lykia (Lycia). Reaching Limyra on the southern coast of Asia Minor on 21 February, Caius died.18 He was just 23 years old. A cenotaph was erected on the Limyrus River to commemorate his brief life.19 At Colonia Obsequens Iulia Pisana (modern Pisa), as likely happened in other communities, the town council decreed that the proper rites must be observed, that matrons should lament his passing, and the doors of temples, public baths and shops must be shut as the women wailed.20 Like his younger brother nineteen months before, Caius’ body was brought under military escort provided by the Cohortes Praetoriae, which had accompanied him on the mission. The cortège was received by the magistrates of the cities it passed through en route to Rome. There a state funeral was held. A period of mourning was declared. The casket containing his ashes was placed in the Mausoleum of Augustus. The silver shields and spears the two brothers had each received on achieving the age of military service were hung side by side in the Curia Iulia.21 It was a poignant memorial to the lives of two young Romans who had once offered so much hope and promise.

In the deaths of Caius and Lucius, Augustus had lost not only his sons and heirs, but the next generation of military leaders as well. His response was typically practical. On 26 June, Augustus adopted Tiberius and M. Agrippa (Postumus), but required Tiberius also to adopt his nephew Germanicus as his son.22 Responding to the surprise development, Tiberius publicly announced ‘hoc rei publicae causa facio’ – ‘this I do for sake of the Commonwealth’.23 Now fully rehabilitated, Tiberius’ tribunician power was restored for ten years.24 Formally a member of gens Iulia, he assumed the new name Ti. Iulius Caesar Augustus f.; in turn his natural son changed his to Drusus Iulius Caesar (Drusus the Younger), and his adopted son similarly became Germanicus Iulius Caesar.

Augustus also set up a new commission to examine the qualifications of senators, which saw several expelled.25 To replenish its thinning ranks with younger and abler talent, he assisted several impoverished men so that they had the wealth to meet the admission requirements.26 These developments offended some. There were several plots to assassinate him – the one alleged to have involved Cn. Cornelius, the son of the daughter of Pompeius Magnus, may have taken place this year.27 Augustus did not press charges against him and even nominated Cornelius for the consulship.28

That summer, the Germanic nations, peaceful for a decade, broke into revolt. Augustus dispatched Tiberius with orders ‘to pacify Germania’.29 Somewhat ironically, his last active combat command prior to his self-imposed exile had been in the same region in 7 BCE. Details of the campaign come to us from the account written by Velleius Peterculus, who served with Tiberius, both as praefectus equitum and legatus legionis.30 He writes as an eyewitness that, on his arrival in Tres Galliae and Germania, Tiberius was warmly received by old soldiers, evocati and veterans who had served with him before:

Indeed, words cannot express the feelings of the soldiers at their meeting, and perhaps my account will scarcely be believed – the tears which sprang to their eyes in their joy at the sight of him, their eagerness, their strange transports in saluting him, their longing to touch his hand, and their inability to restrain such cries as ‘Is it really you that we see, commander?’ ‘Have we received you safely back among us?’ ‘I served with you, Commander, in Armenia!’ ‘And I in Raetia!’ ‘I received my decoration from you in Vindelicia!’ ‘And I mine in Pannonia!’ ‘And I in Germania!’31

It was time to go on the offensive. Velleius’ account indicates that Tiberius began his punitive campaign against the Germanic nations of the western and central sectors, seemingly following his younger brother’s plan of 12 BCE.32 In charge of one of the army groups he put the newly appointed Legatus Augusti Sentius Saturninus – relieved from his consulate by suffect Clodius Licinius – who had previously served as a legatus legionis in Germania under his father, and thus was quite familiar with the terrain.33 The two commanders coordinated their operations, attacking on multiple fronts. The Cananefates and Cherusci – both former allies – were beaten, along with the Attuari and Bructeri. Tiberius’ forces crossed the Weser River and marched deep into territory on the other bank.34 Near the Weser, temporary or semi-permanent camps were established at Minden and Hameln. Traces of a Roman marching camp with evidence for some thirty baking ovens have also been found at Barkhausen, Porta Westfalica that has produced military finds contemporary with this period.35

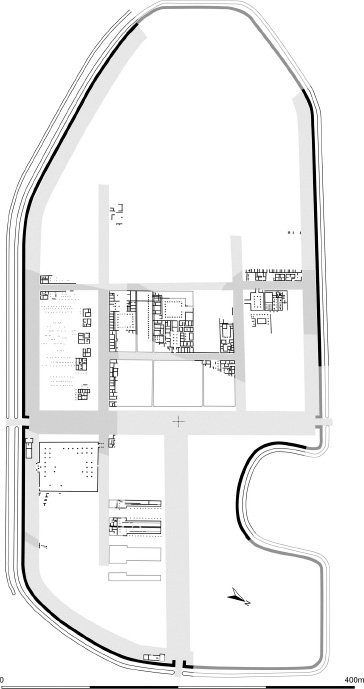

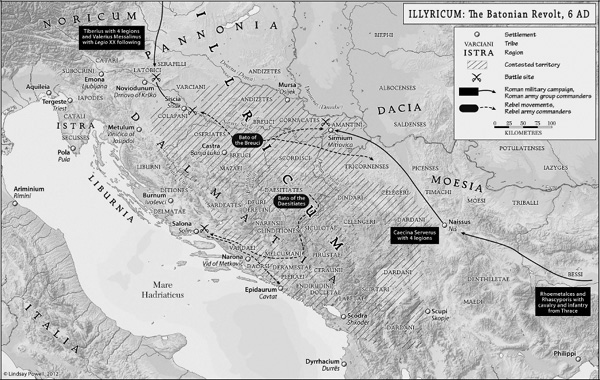

Map 18. Anreppen Roman Fort, Germany.

Unusually for a Roman military campaign, the war lasted into the month of December. Before his departure for Rome, Tiberius ‘pitched his winter camp at the source of the Lupia, in the very heart of the country’, evidently reversing his earlier defensive posture.36 On that river, a new forward military base, located some 100 kilometres (65 miles) east of Haltern, or 185 kilometres (114 miles) from Vetera, was founded at Anreppen.37 At 23 hectares, the oval-shaped fortress was large enough for a single legion and contained all the standard interior military buildings, each constructed of wood, including an outsize principia or headquarters, as well as a praetorium or house for the resident commander (map 18). From Anreppen, the military road apparently continued further east in the direction of modern Paderborn, where another fort is suspected.38

| L. Valerius Potiti f. Messalla Volesus | Cn. Cornelius L. f. Cinna Magnus | |

| suff. | C. Vibius C. f. Postumus | C. Ateius L. f. Capito |

Encouraged by his success the previous year, Tiberius eagerly returned to Germania in the spring.39 In this second phase of the relaunched Bellum Germanicum, he escalated the war, taking it to the nations of the central, northwestern and eastern sectors. Under his command were five legions: Legiones I, V Alaudae, XVII, XIIX and XIX (table 2). Recorded as engaged in this season were the Chauci, the Langobardi and, after he crossed the Elbe River, the Semnones and Hermunduri.40 Having the advantage of offence, Tiberius was the subject of an attack only once, during which he inflicted major casualties on the unnamed enemy.41 Tiberius replicated his brother’s use of a fleet to support the expeditionary force, sailing transports down the Elbe River, ‘and after proving victorious over many tribes effected a junction with [Ti.] Caesar and the army, bringing with it a great abundance of supplies of all kinds’.42 The troops celebrated the progress with acclamations for Augustus (his seventeenth) and Tiberius (his third).43

Table 2. Dispositions of the Legions, Spring 5 CE (Conjectural).

| Province | Units | Legions |

| Hispania Tarraconensis | 4 | II Augusta, IIII Macedonica, VI Victrix, X Gemina |

| Germania | 5 | I, V Alaudae, XVII, XIIX, XIX |

| Raetia | 2 | XVI Gallica, XXI Rapax |

| Illyricum | 5 | VIIII Hispana, XIII Gemina, XIV Gemina, XV Apollinaris, XX |

| Thracia-Macedoniaque | 3 | IV Scythica, VIII Augusta, XI |

| Galatia-Pamphylia | 2 | V Macedonica, VII Macedonica |

| Syria | 4 | III Gallica, VI Ferrata, X (Fretensis), XII Fulminata |

| Aegyptus | 2 | III Cyrenaica, XXII Deiotariana |

| Africa | 1 | III Augusta |

Sources: Appendix 3; Lendering (Livius.org); Mitchell (1976); Šašel Kos (1995); Swan (2004), table 5, p. 165; Syme (1933 and 1986).

The commander-turned-historian relates a curious story of an encounter between Tiberius and an awestruck German:

We were encamped on the nearer bank of the aforesaid river, while on the farther bank glittered the arms of the enemies’ troops, who showed an inclination to flee at every movement and manoeuvre of our vessels, when one of the barbarians, advanced in years, tall of stature, of high rank to judge by his dress, embarked in a canoe (made as is usual with them of a hollowed log) and, guiding this strange craft, he advanced alone to the middle of the stream and asked permission to land without harm to himself on the bank occupied by our troops and to see Caesar. Permission was granted. Then he beached his canoe, and, after gazing upon Caesar for a long time in silence, exclaimed: ‘Our young men are insane, for though they worship you as divine when absent, when you are present they fear your armies instead of trusting to your protection. But I, by your kind permission, Caesar, have today seen the gods of whom I merely used to hear; and in my life have never hoped for or experienced a happier day.’ After asking for and receiving permission to touch Caesar’s hand, he again entered his canoe, and continued to gaze back upon him until he landed upon his own bank.44

The second campaign was a successful one for the adopted son of Augustus. In lofty language, Velleius Paterculus writes:

All Germania was traversed by our armies, races were conquered hitherto almost unknown, even by name . . . All the flower of their [Germanic] youth, infinite in number though they were, huge of stature and protected by the ground they held, surrendered their arms, and, flanked by a gleaming line of our soldiers, fell with their leaders upon their knees before the tribunal of the commander.45

In contrast, unimpressed by the Roman commander’s comings and goings, Dio writes that:

expeditions against the Germans also were being conducted by various leaders, especially Tiberius. He advanced first to the river Visurgis and later as far as the Albis, but nothing noteworthy was accomplished at this time.46

Tiberius led his expeditionary force back to its camps in time for winter. For some units this would mean breaking new ground. During the campaign he had developed a strategic plan for the conquest of the remaining lands of Germania under the control of the Marcomanni. In readiness for its execution, two new legionary bases were established. In what is now Bavaria, located 147 kilometres (91 miles) east of the Rhine, a camp was pitched at Marktbreit on a meander in the Main River, and buildings of timber were erected inside it (map 19).47 Another even larger camp, containing an area of almost 58 hectares, was dug on an escarpment overlooking the Danube River at Carnuntum (or Karnuntum near modern Vienna, Austria).48 While the legionaries toiled, Tiberius travelled to Rome – but he would be back.

M. Agrippa (Postumus), Augustus’ 18-year-old adopted son, had since become eligible for military service. While he was enrolled among the youths of military age, he had still not been accorded the same honours and privileges as his brothers, even after their deaths.49 The reason why is still debated.

If Agrippa was unhappy at his adoptive parent’s treatment of him, it was nothing compared to the deep dissatisfaction felt among the regular troops. At issue was the compensation and terms of their service:

The soldiers were sorely displeased at the paltry character of the rewards given them for the wars which had been waged at this time and none of them consented to bear arms for longer than the regular period of his service.50

It was important to address this issue without delay. After the mass discharges in 14 BCE, the disgruntled men protesting their pay in 5 CE were the ones who had replaced them, agreeing to serve for sixteen years.51 Now many were overdue for retirement and a new intake of recruits had to be found to fill their ranks. They in turn might be dissuaded from joining if they heard the complaints from the veterans. Augustus had last reviewed army remuneration and retirement benefits in 13 BCE. Now it was for the Senate to find a solution:

Map 19. Marktbreit Roman Fort, Germany.

It was therefore voted that 5,000 drachmai [HS20,000] should be given to members of the Cohortes Praetoriae when they had served sixteen years, and 3,000 drachmai [HS12,000] to the other soldiers when they had served twenty years.52

For both the praetoriani and caligati, this meant serving an additional four paid years, but by offering a large cash bonus at the end of their terms the Senate had sweetened the deal and helped Augustus avert a potential crisis of confidence in the ranks. Upon the unswerving co-operation of the army, the security of the empire – and Augustus’ leadership position – relied.

| M. Aemilius Paulli f. Lepidus | L. Arruntius L. f. | |

| suff. | L. Nonius L. f. Asprenas |

Of the three consuls appointed for the year, two were related to men who had served with Augustus in wartime. The suffect consul L. Nonius Asprenas, nephew of P. Quinctilius Varus, was now well-positioned for a future military post of his own.53 Varus himself assumed command of Germania from Sentius Saturninus, whose military acumen was being deployed elsewhere.54 Varus’ mission from Augustus was clear: to expedite the process of pacification of the Germanic nations, including the levying of taxes upon them.55 After two decades of conquest, the province was now a fist-shaped spur of territory extending northeast from the Rhine and bounded by the free, allied nations along the North Sea coast and Elbe and Main Rivers.56 Varus deployed detachments from the five legions and several auxiliary cohorts under his command across the region, and embedded them with the Germanic communities as peace-keepers, police and road-builders:

Soldiers of theirs were wintering there and cities were being founded. The barbarians were adapting themselves to Roman ways, were becoming accustomed to holding markets, and were meeting in peaceful assemblies.57

Germania was a bright spot in a darkening geo-political sky. This year the carefully constructed world order managed together by Augustus and the Senate came under threat. ‘During this period,’ writes Dio:

many wars also took place. Brigands overran a good many districts, so that Sardinia had no senator as governor for some years, but was in charge of soldiers with knights as commanders. Not a few cities rebelled, with the result that for two years the same men held office in the provinces which belonged to the People and were appointed instead of being chosen by lot; of course the provinces which belonged to Caesar were, in any case, assigned to the same men for a longer period.58

In Africa, old tensions burst into a new violent conflict. The Isauri raided into Roman territory, initially ravaging settlements, but quickly escalating into a fullblooded war.59 Only when military resources were ranged against them were the tribesmen finally driven out. The neighbouring Gaetuli of Numidia also chose this moment to rebel against their king, Iuba II.60 This highly educated man had proved a reliable ally – perhaps too willing to kowtow to the Romans in the eyes of his subjects. His alignment with Augustus was at odds with the independencemindset of many in his kingdom who saw an opportunity to challenge their regent. His early attempts to contain the rebellion failed. The insurgents then took their fight to the Roman province of Africa, destroying property and killing many of its people. Proconsul Cossus Cornelius Lentulus (consul 1 BCE), an impoverished patrician with a distinguished pedigree, led a campaign against them. He had a single legion under his command – Legio III Augusta. No details of the war have come down to us, yet Dio’s cryptic description that the Romans took heavy casualties fighting the rebel army is significant. The lightly armed Gaetuli, it seems, were initially able to inflict damage upon the better-equipped legionaries. Dogged determination and unbending discipline, however, finally extinguished the menace in Africa and Numidia. Receiving Lentulus’ after-action report that order had been restored to the region, the Senate awarded its man triumphal ornaments and the unique war title Gaetulicus.61

In the East, Herodes’ successor was proving to be a thoroughly incompetent ruler.62 It was decided – almost certainly with Augustus’ consent and, perhaps, at his instigation – to remove Archelaos beyond the Alps to Vienna (modern Vienne, France), essentially banishing him.63 This was more than regime change: his realms of Idumaea, Iudaea and Samaria were now to be annexed and merged together as a new Province of Caesar.64 The office of Praefectus Iudaeorum was created and an eques, one Coponius, was appointed to it, reporting to the Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore of Syria, P. Sulpicius Quirinius.65 Establishing direct Roman authority over Iudaea quickly proved problematic. The attempt by the new procurator, Cyrenius, to conduct a census to assess the tax base of the province was met initially with vocal resistance, until the high priest Joazar persuaded the people to comply. Most, but not all, followed his counsel:

Yet was there one Iudas, a Gaulanite, of a city whose name was Gamala, who, taking with him Sadduc, a Pharisee, became zealous to draw them to a revolt, who both said that this taxation was no better than an introduction to slavery, and exhorted the nation to assert their liberty.66

Iudas’ protest was religious rather than political, one based on renouncing worldly infatuation with material goods in favour of developing a spiritual life. According to Josephus, this new doctrine rapidly swept across the nation, though the author of the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament states only 400 people joined the man’s cause.67 However, the intensity of the following led to conflict with the authorities. Josephus mentions great robberies and assassinations of unnamed officials. That the other Roman historians make no mention of them infers that they were skirmishes or minor infractions.68 The sedition was quelled within the year. The fate of Iudas of Gamala is not recorded by Josephus, but the Acts states he was killed and his followers then dispersed.69 Quirinius could continue the assimilation of the new territory at will.

The nascent province between the Rhine and Elbe rivers, meanwhile, remained a work in progress. The damaged relations with the native peoples of Germania, who had revolted the year before, needed to be repaired. Trust had to be re-established. There also remained an ever-present threat the Romans perceived as existential, one that could yet destabilize the balance of power in the region. The land north of Noricum, beyond the Danube, was occupied by the Marcomanni. They were led by a respected but feared king, Marboduus. He was an intelligent man who had been educated in Rome as a private individual rather than as a hostage, and been befriended – like Iuba II – by Augustus.70 Around 10 BCE, Marboduus rejoined his people, who were then living close by the Main River, and assumed the highest social position among them.71 He formed alliances with neighbouring nations and tribes and convinced them to relocate away to territory further east, in the region of Bohaemium (Bohemia in the modern Czech Republic), to avoid encroachment by, and conflict with, the Romans.72 He knew how effective they were at war. He had learned the lessons of military science from living for some sixteen years among the Romans – perhaps from service with the auxilia – and applied them to his own army, organizing and training his own soldiers like theirs. By 6 CE he had an armed force approaching 70,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry.73

Tiberius had conceived his invasion plan of Bohaemium as part of his greater mission to pacify Germania the previous year, or even earlier (fig. 11).74 The scale of the operations and number of units involved imply careful preparations undertaken over many months.75 The strategic plan called for a two-pronged attack to surround, cut-off and crush the Marcomanni. The army group under Tiberius’ command would strike directly north-northwest from Carnuntum on the Danube, resourced with troops drawn from Raetia and others provided by Legatus Augusti M. Valerius Messalla Messallinus of Illyricum; simultaneously, Sentius Saturninus would lead his army group east from Mogontiacum and forts within province Germania along the Main River, march through the territory of the Chatti and cut a pathway through the dense Hercynia Silva.76 Up to twelve legions and an unspecified number of auxiliary cohorts of infantry, alae of cavalry and mixed units were in position, perhaps representing a combined force of 80,000 men – the largest deployment for a single campaign since the Cantabrian and Asturian War of 26 BCE77 (see Order of Battle 3).

The order for the advance was given:

Caesar had already arranged his winter quarters on the Danubius, and had brought up his army to within five days’ march of the advanced posts of the enemy; and the legions which he had ordered Saturninus to bring up, separated from the enemy by an almost equal distance, were on the point of effecting a junction with Caesar at a predetermined rendezvous within [a] few days.78

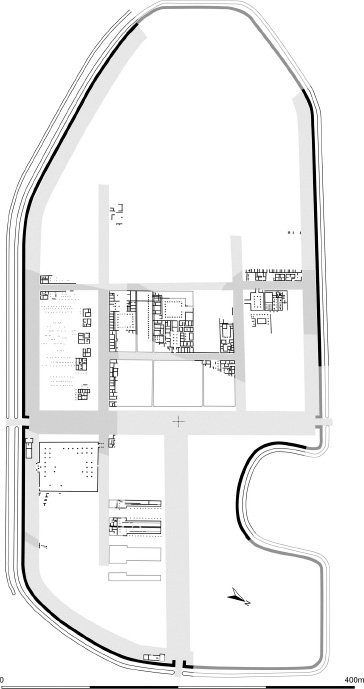

Figure 11. After Agrippa’s death, Tiberius became Augustus’ right-hand man. A talented commander, he fought many wars for the princeps and was popular with the soldiers.

Roman finds on the left bank of the Danube and its confluence with the March River approximately 10 kilometres (6 miles) east of Carnuntum at Bratislava-Devín may mark the actual crossing point of Tiberius’ army group.79 Following the course of the March, it moved inland at a steady pace in search of its target.80

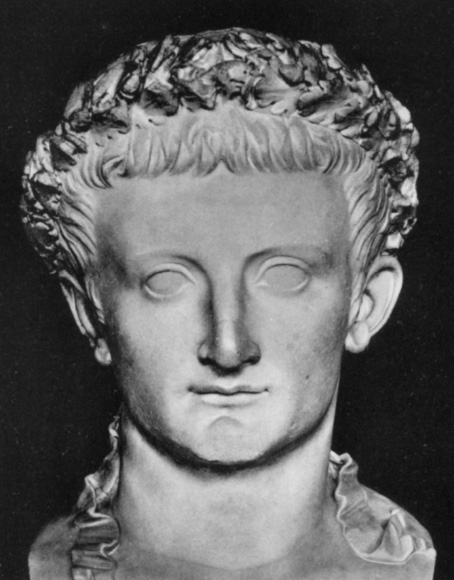

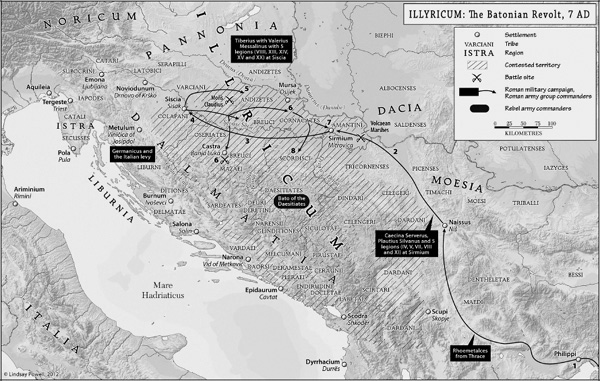

Order of Battle 3. Illyricum, 6–9 CE. Units of ethnic auxilia are recorded as having served in Illyricum.

Then the unexpected happened. Far behind the advancing Roman columns, the supposedly pacified people of the north of Illyricum rose up in revolt.81 The longsimmering frustrations borne of Roman occupation, heated by perceived abuses concerning tribute obligations, now boiled over. The chief of the Breuci of the Pannonii confederacy – a man named Bato – led his people in a direct assault against the Roman town of Sirmium.82 No one was spared from the violence:

Roman citizens were overpowered, traders were massacred, a large detachment (vexillatio) of veterans stationed in the region, which was most remote from the commander, was exterminated to a man.83

The inhabitants withstood Bato’s onslaught, but the brazen attack could not go unpunished. Closest geographically and able to deal quickest with the insurrection was A. Caecina Severus, Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore of neighbouring Thracia Macedoniaque. He led the counterattack and soon ‘everywhere was wholesale devastation by fire and sword’.84 He engaged the rebels at the Drava River, and in the mêlée the Breuci suffered heavy casualties and were eventually forced to retreat, but not without first inflicting damage upon the Romans. The rebels’ audacious resistance proved a great draw for the discontented, and more men soon swelled the ranks of the insurrectionists.85

As a defeated people, the nations of Illyricum were required to pay tribute. One of the possible causes of the rebellion was the additional demand of a conscription levy imposed by the Romans upon the male populations of the subject nations of Illyricum for the war against Marboduus.86 As subjects, they were obligated to provide men for the auxilia and serve alongside Roman troops when required. In preparation for the Bellum Marcomannicum, propraetorian legate Messallinus had issued an edict for all able-bodied men to present themselves for duty.87 Dio reports that when the auxiliaries assembled together they realized just how large a force and how strong in arms they were; then one of them, Bato of the Daesidiates nation – a man with maxima auctoritas or ‘greatest prestige’, according to Velleius Paterculus – took the lead to openly incite rebellion.88 Their choice was either to put their lives at mortal risk in a war that they did not themselves want in order to benefit the Romans, or to fight the Romans and by doing so liberate their own homeland from the oppressors. Many decided to join him. Bato’s highly motivated force promptly defeated the first Roman troops sent against it.89

The rebel army quickly swelled to 90,000–100,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry.90 Little is known about their organization or mode of fighting, but of the Iapodes tribe, who lived in the far northwestern corner of Illyricum, Strabo writes that ‘they are indeed a war-mad people’, noting ‘their armour is Celtic, and they are tattooed like the rest of the Illyrii and the Thraci’.91 The most widely used offensive weapon was the long, heavy spear (lancea, sibyna) with a flat leaf-shaped bronze or iron blade at the tip.92 Warriors of the Illyrii used arms and armour derived from Greek models, preferring the curved, single bladed machaira or the sica, a short curved sword the Romans associated with assassins.93 Noted for their horsemanship, many warriors of the Western Balkans often rode into battle, dismounted and continued to fight on foot.94 Small-scale ambuscades and surprise attacks on troops on the march were common tactics.

Separately, Bato and the men of the Daesidiates moved on Colonia Martia Iulia Salona, hoping to take the city from which the Romans administered the province. The trapezium-shaped stronghold on the Dalmatian coast was fortified with stout walls and towers.95 The details of the attack on the city of Salona are lost to us. The defenders managed to hold their town and, in the ensuing battle, Bato himself was wounded when struck by a stone, perhaps launched from a Roman sling or ballista.96 The rebel leader wounded, the siege collapsed and the retreating insurgents fanned out along the Dalmatian coast, wreaking havoc on the unprotected communities and settlements as they passed through. At Apollonia they engaged the Romans again, initially seeming to suffer defeat before snatching an unexpected victory.97

The princeps feared Illyricum could yet be lost, and ‘such a panic did this war inspire that even the courage of Caesar Augustus, rendered steady and firm by experience in so many wars, was shaken with fear’.98 Emergency measures were implemented:

Troops were accordingly levied: all the veterani were everywhere called out; and not only men, but women were compelled to provide freedmen for soldiers, in proportion to their income. The princeps was heard to say in the Senate, that, unless they were on their guard, the enemy might in ten days come within the sight of the city of Rome. The services of Roman senators and equites were required, according to their promises, in support of the war.99

Tiberius was officially placed in command of counterinsurgency operations.100 He was faced with a major dilemma: either to continue with the mission in Germania, but divert resources to quell the insurgency; or to suspend operations altogether, deal with the rebellion in Illyricum as the priority and return to the invasion another season.101 He settled for a truce with Marboduus and began a full tactical withdrawal of his forces and their redeployment to the Western Balkans.102 It was a victory of sorts. Recognizing that the enemy had been forced to make a pact with the Romans, Tiberius and Saturninus were both granted triumphal honours, the former also being awarded a consulship.103 But greater perils lay ahead that would test both commanders’ skills.

While Tiberius organized the withdrawal of his army from the right bank of the Danube, Messallinus left with a small detachment from Legio XX (map 20); Tiberius would follow with the main army group as soon as he could.104 In this first year of war, eight legions – equivalent to 40,000 men at full strength – plus an unknown number of auxiliary cohorts were committed.105 The Bellum Delmaticum – also known by its other moniker Bellum Batonianum, the ‘War of the Batos’ – would later be considered ‘the most grave conflict since Rome’s struggle with Carthage’.106

Despite still recovering from his injury, Bato of the Breuci nevertheless led his force in person to intercept Messallinus. The insurgents gained the upper hand in open battle, but lost their advantage when later ambushed by the Romans.107 Bato realized he could not decisively beat the Romans with his small force. He needed many more men. The obvious man to approach was Bato of the Daesidiates, who was achieving results through his own efforts in the south of the country.108 The two chiefs met and agreed to cooperate and share the war command. They assembled their combined army north of the city of Sirmium on a mountain called Mons Alma (Fruška Gora), hoping to exploit the advantage and protection offered by high ground. To beat them, the Romans would have to fight uphill.

Severus had, meanwhile, set off from newly incorporated Moesia, counted a Province of Caesar. Before leaving, he had sought assistance from Rome’s ally Roimetalkes to augment his numbers.109 Responding quickly to the request, the king actually managed to bring his lightly armed, but tough Thracian units in theatre ahead of the Roman commander. The rebels resisted the Romans on the first assault but, under the additional numbers from Roimetalkes’ army, they eventually crumbled. Hardly had Severus celebrated his victory when he discovered he had problems of his own. The Daci and Sarmatae had taken advantage of his absence and invaded his province unopposed; at the same time, the Dalmatae entered the territories of their neighbours in Illyricum and stirred up revolt there.110 The legate of Moesia had no choice but to return urgently and regain control of it.

Tiberius and Messallinus arrived in Illyricum. They set up their operational headquarters at Siscia with the resident garrison commander M’. Ennius; soon they found themselves trapped within its stout walls and under a sustained rebel assault.111 Despite the setbacks, there were Roman successes. Eager to take part in the campaign, the former cavalry commander and quaestor designate for 7 CE, Velleius Paterculus, set off from Rome.112 He had accepted the post of legatus assigned to Tiberius and duly arrived in Siscia with reinforcements.113 Messallinus and his army found themselves surrounded by a greater number of enemy soldiers, but Roman discipline held and the enemy was routed, with 20,000 fleeing the field.114 When news of his victory reached Rome, Messallinus was accorded the honour of triumphal ornaments.115

By this time the rebels had learned the wisdom of not engaging the Romans in open battle. Instead they used their knowledge of terrain, skills with light arms and agility to wage a guerrilla war, which greatly disadvantaged the heavily armed legionaries.116 They successfully stretched their resistance into the winter, when the legions normally retired to camp, and even invaded the neighbouring Roman province of Macedonia, causing destruction wherever they went.117 Once they reached Thracia, their south and eastward advance was blocked by Roimetalkes, assisted this time by his brother Raskiporis (Rhascyporis).118 Faced with inclement weather, the rebel army retreated to the hills of Illyricum, from where they launched hit-and-run raids upon the Romans at will.

Augustus watched the ‘War of the Batos’ from afar with deepening concern.119 He had personal experience of the terrain and the enemy from his two tours in Illyricum forty-two years before, and even sustained injuries in combat during them.120 Dio writes that he believed that the campaign should have been over quickly and suspected that Tiberius was deliberately impeding progress so that he could have an army under his direct control.121 Yet the letters he sent to Tiberius – at least the examples preserved by Suetonius – show that the princeps actually extolled his virtues as a consummate general, praised his prudence and emphasized that the fate of the nation depended on his continuing good health and prudent decision-making:

Map 20. Military operations in Illyricum, 6 CE.

Farewell, Tiberius, most charming of men, and success go with you, as you war for me and for the Muses. Farewell, most charming and valiant of men and most conscientious of generals, or may I never know happiness.

I have only praise for the conduct of your summer campaigns, dear Tiberius, and I am sure that no one could have acted with better judgment than you did amid so many difficulties and such apathy of your army. All who were with you agree that the well-known line could be applied to you: ‘One man alone by his foresight has saved our dear country from ruin.’122

This time of crisis should have been the opportunity for his youngest adopted son M. Agrippa (Postumus), now eligible for military service, to prove himself. Instead he spent his time fishing, drinking, bickering and acting in ways others interpreted as depraved or mad.123 When he argued that he had been denied his natural father’s – that is M. Agrippa’s – inheritance and denigrated Livia, Augustus finally disowned, disinherited and banished him to the small island of Planasia off Corsica.124

There was only one close relative left whom the princeps could turn to. He ordered Germanicus Caesar – then holding the junior rank of quaestor – to assemble an army and go to assist Tiberius.125 This was the 21-year-old’s first chance to gain military experience and to prove his mettle; he was two years younger than his father Nero Claudius Drusus had been when he set out on his first mission.126 Germanicus grasped the opportunity eagerly. From the outset he faced two formidable challenges. Firstly, he had no training in military matters. Secondly, he had to build his army from scratch by himself. A levy (dilectus ingenuorum) of the free-born citizen population called by Augustus produced the men, supplemented with liberti (freedmen, manumitted or former slaves) and slaves whose freedom had been bought expressly to recruit them into military service.127 Nothing is recorded of the organization of his Cohortes Voluntariorum, or how they were equipped or trained, but at the end of the year his irregular army – perhaps numbering Cohortis Apulae Civium Romanorum and I Campana among them – was ready for active deployment.128 Intending to reach the war zone in time for the new campaign season, Germanicus led his men out of Rome, almost certainly accompanied by two cohorts of Praetoriani for his own protection.

The fact that Augustus resorted to conscription confirms the real anxiety he felt at the worsening situation in the Western Balkans. Velleius Paterculus describes him as visibly ‘shaken with fear’.129 Ever mindful of the delicate state of public finances, to pay for Germanicus’ conscript unit Augustus levied a 2 per cent tax on the sale of slaves and redirected funds from the budget for scheduled gladiatorial games.130 Furthermore, Augustus suspended the annual transvectio review of the equestrians in the Forum Romanum.131

The turbulent events of 6 CE highlighted not only the vital role the army played in maintaining the security of the imperium of the Roman People, but also the precariousness of its funding. The army now comprised twenty-eight legions. The annual operating cost in salaries, equipment, animals and supplies was now immense.132 To pay for the programme, Augustus made the first contribution that year to a military fund, the Aerarium Militare, with a commitment to make annual deposits in future.133 He accepted voluntary contributions from allied kings and certain confederate communities, but he took nothing from private citizens – although, according to Dio, a considerable number made offers of their own free will, or so they said.134 Even with his generous deposits, withdrawals from the account would exhaust the monies in short order. More cash was needed. Augustus encouraged the Senate to propose ways and means to ensure the Aerarium would be properly funded and invited them to write down their ideas and submit them for his consideration.135 He already knew, of course, how he would do so. The method had been used before and later been suspended:

At all events, when different men had proposed different schemes, he approved none of them, but established the tax of 5 per cent on the inheritances and bequests which should be left by people at their death to any except very near relatives or very poor persons, representing that he had found this tax set down in Caesar’s memoranda.136

To administer the fund, a board was appointed of three ex-consuls, chosen by lot, to serve a term of three years; they would be entitled to two lictors each and to request any assistance they deemed necessary.137 With their help, Augustus was able to reduce several types of expenditure or to cut them altogether.

Security at home also received the princeps’ attention. This year, during which the citizens of the city of Rome suffered through a combination of severe famine and devastating fires, Augustus founded the Vigiles Urbani, the ‘City Watch’, as a paramilitary firefighting force.138 Commanded by an equestrian Praefectus Vigilum whom he personally appointed, the 6,000 men filling its ranks were recruited from among freedmen.139 The Vigiles also served as the city’s night watch and helped the Cohortes Urbanae to enforce public order, arrest thieves and capture runaway slaves.140 Funded by a tax on the sale of slaves, the Vigiles had barracks located in the city and proved very popular with the citizens.141

| Q. Caecilius Q. f. Metellus Creticus Silanus | A. Licinius A. f. Nerva Silianus | |

| suff. | [-]. Lucilius Longus |

Germanicus and his cohorts of volunteers reached Illyricum in time for the new campaign season. Roman forces were now deployed right across the region, intent on quelling the Great Illyrian Revolt (map 21). Tiberius, Messallinus and their men were still unable to leave Siscia. From the neighbouring provinces,

A. Caecina Severus and M. Plautius Silvanus marched with five legions, bringing the total under Tiberius’ command to ‘10 legions, more than 70 auxiliary cohorts, 10 alae of cavalry and 10,000 veterans and, in addition, a large number of volunteers and numerous cavalry of the [Thracian] king’ – a combined force of some 145,000 men, equivalent to almost half of Roman troops on active service.142 ‘Never,’ writes Velleius Paterculus, ‘had a greater army been assembled in one place since the civil wars.’143 Caesar Augustus was determined to destroy the opposition once and for all.

The Romans may have believed that, with such resources, victory was assuredly theirs. They had underestimated the guile of their adversary. The legions brought by Caecina Severus and Silvanus, augmented by Roimetalkes and his Roman-trained Thracian infantry and cavalry, however, found themselves surrounded by the rebels.144 In the ensuing battle – the location of which is unknown – the cavalry of the Thraci was routed, the auxiliary infantry and cavalry were chased away and even among the legionaries ‘some confusion took place’.145 The Roman casualties included a tribunis militum, praefectus castrorum, primus pilus and other centurions of the legions and several praefecti of auxiliary cohorts.146 It was a shambles. In the heat of battle the centurions – the backbone of the Roman army, who could be relied upon to keep cool heads – applied the basic combat doctrine and maintained unbending discipline with cold efficiency. Paterculus writes in praise of the rankers:

The courage of the Roman soldiers, on that occasion, gained them more honour than they left to their officers, who, widely differing from the practice of the commander-in-chief [Tiberius], found themselves in the midst of the enemy, before they had ascertained from their scouts in which direction they lay.147

They saved the day. ‘The legions, encouraging one another, made a charge upon the enemy,’ Paterculus writes, ‘and, not content with standing their ground against them, broke their line, and gained an unexpected victory.’148

Severus followed the course of the Bosut River (a tributary of the Sava now in eastern Croatia) and marched right into a trap. The combined forces of the two Batos rushed upon his marching camp near the Volcaean Marshes, near the site of later Cibalae (Vinkovici).149 Dio writes that the rebels ‘frightened the pickets outside the ramparts and drove them back inside’.150 However, once behind the turf rampart surmounted by its fence of sharpened stakes (sudes) lashed together, the Roman soldiers’ resolve returned; with their centurions barking orders at them, they stood their ground and gradually repulsed the besiegers. Learning from this and other incidents, the Romans adapted their tactics. They divided into their cohorts and centuries so ‘that might overrun many parts of the country at once’.151 These smaller detachments would form, in effect, a mobile army.

Tiberius finally broke out from Siscia and began his advance to the east. He quickly contained many rebels in the area between the Drava and Sava rivers at Mons Claudius (Papuk Hills).152 The Augustan military camp at Obrežje along the Sava River may date from this action.153 Having made such little progress against the insurgents, this small victory was important to boosting morale of his men.154 Germanicus’ army also enjoyed success when he clashed with the Mazaei nation.155 Listed as Pannonii by Strabo, the Mazaei lived on the transitional grassy plain upon which Banja Luka now stands in modern Bosnia-Herzegovina.156 The enthusiasm of the young commander and the effectiveness of his soldiers’ training proved decisive. Germanicus ‘conquered in battle and harassed the Mazaei’, writes Dio.157 His army remained in the country in sight of the Dinaric Alps through the winter in case of a counterinsurgency. Whether Germanicus stayed or returned to brief Augustus is not disclosed in the extant records. In his eagerness for news of the war, Augustus had relocated to Ariminum (modern Rimini).158 Tiberius likely stayed there with the princeps, discussing military strategy with him until the spring of the following year.

Map 21. Military operations in Illyricum, 7 CE.

Having completed his proconsulship in Africa, Cossus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus returned to Rome. There this noble and respected man celebrated his well-deserved triumphal ornaments.159

| M. Furius P. f. Camillus | Sex. Nonius L. f. Quinctilianus | |

| suff. | L. Apronius C. f. | A. Vibius C. f. Habitus |

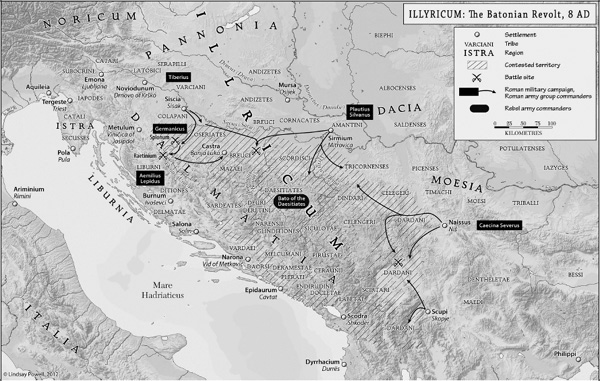

The Bellum Batonianum entered its third year. Germanicus Caesar and his troops continued their operations by moving into the mountains (map 22). Their target was Splanaum – or Splonum to the Romans – on the Dalmatian side of the Dinaric Alps.160 It was a populous region and the centre of mining in Illyricum, producing ores for the precious metals industry.161 Splonum’s remote location, strong fortifications and ‘vast number of defenders’ posed a considerable challenge to the young man and small army.162 Given that time was not on the novice commander’s side, blockading the defenders – in the hope of starving them out – was not an option. Having brought with him a quantity of siege weapons, Germanicus attempted a direct assault. However, even ‘high technology’ tension and torsion weapons did not give the Romans the decisive tactical edge they needed in this remote situation. Finding ‘he had been unable to make any headway either with engines or by assaults’, the Roman attackers had reached a stalemate.163 Frustrated, one Pusio:

a Germanic horseman, hurled a stone against the wall and so shook the parapet that it immediately fell and dragged down with it a man who was leaning against it. At this the rest became alarmed and in their fear abandoned that part of the wall and ran up to the citadel.164

The audacious act changed the odds. Through the breach, the besieging troops poured into the fortress. The Roman troops exacted a terrible revenge. A last stand by the defenders would be futile. Shortly after they surrendered the citadel and themselves.165

Map 22. Military operations in Illyricum, 8 CE.

Germanicus advanced deeper into rebel-held territory with his irregular troops. On the way they captured several strongholds; the fall of Raetinum is recorded in gruesome detail by Dio.166 He writes:

The enemy, overwhelmed by their numbers and unable to withstand them, set fire of their own accord to the encircling wall and to the houses adjoining it contriving, however, to keep it so far as possible from blazing up at once and to make it go unnoticed for some time; after doing this they retired to the citadel. The Romans, ignorant of what they had done, rushed in after them, expecting to sack the whole place without striking a blow; thus they got inside the circle of fire, and, with their minds intent upon the enemy, saw nothing of it until they were surrounded by it on all sides. Then they found themselves in the direst peril, being pelted by the men from above and injured by the fire from without. They could neither remain where they were safely nor force their way out anywhere without danger. For if they stood out of range of the missiles, they were scorched by the fire, or, if they leaped back from the flames, they were destroyed by the missiles; and some who got caught in a tight place perished from both causes at once, being wounded on one side and burned on the other. The majority of those who had rushed into the town met this fate; but some few escaped by casting corpses into the flames and making a passage for themselves by using the bodies as a bridge. The fire gained such headway that even those on the citadel could not remain there, but abandoned it in the night and hid themselves in subterranean chambers.167

By the next day, the charred ruins of Raetinum had fallen to Germanicus.

Despite having a proven talent for combat command and a formidable force of ten legions, Tiberius nevertheless suffered setbacks.168 As the war dragged on seemingly without end, his often idle troops became restless in the humid heat of the Balkan summer. Facing the possibility of outright mutiny, Tiberius urgently needed a new strategy that could break the impasse and bring his troops victory. His answer was to realign the expeditionary army. ‘He made three divisions of them,’ writes Dio, ‘one he assigned to Silvanus and one to Marcus Lepidus, and with the rest he marched with Germanicus against Bato.’169 For Germanicus, who now led his own army group comprising legions and auxiliaries as well as his own irregular unit, this was a major promotion and a public recognition of his military achievement.

The rebels were restless too. They began to squabble among themselves and committed acts of treachery against each other. Having betrayed a certain Pinnes with the connivance of members of the tribe, Bato of the Breuci now ruled alone over the nation. The two leaders of the Great Illyrian Revolt had since become estranged and grown deeply suspicious of each other. There was a struggle and the Breucian was betrayed by his own people; he was handed over to Bato of the Daesidiates and summarily executed.170 Many of the Breuci rightly felt betrayed and raged against their former allies.

The division among the rebels created just the opportunity the Romans needed. Legatus Silvanus now launched an offensive against them. Disunited and taken by surprise, the opposition collapsed. He defeated the war-weary Breuci and their allies, writes Dio, ‘without a battle’.171 The disaffected warriors of north Illyricum soon sued for peace. On 3 August, they surrendered to Silvanus at a place on the Bathinus (Bosnar?) River.172 Bato of the Daesidiates, however, would not yield. The men still loyal to him retreated to the passes leading to the relative safety of their homeland in central Illyricum, ravaging the surrounding lands as they moved and resisting Roman attempts to defeat them for several months more.173

Quelling the rebellion in Illyricum had become a protracted, grinding struggle of asymmetric warfare. The theatre of operations now concentrated on the lands of the Perustae, Daesidiates and Dalmatae, but the jagged hillsides and craggy vales of central Illyricum were unsuited to Roman tactics and equipment.174 While the rebels were dispersed in smaller bands, the Romans were forced to waste time and effort tracking them down. However, many retreated to their fortified places, confident they could wait out the inevitable oncoming storm. The Romans were experts in siege craft. Strongholds that had earlier successfully held out against Tiberius and his deputies’ armies began to fall, one by one, including Seretium, which had resisted the Romans right from the beginning. Silvanus and Lepidus rapidly overwhelmed the insurgents they encountered too.

Tiberius and Germanicus had to work harder for their victories. Bato of the Daesidiates had since moved his base of operations to Andetrium (Muč), a fort built on a rocky escarpment with steep sides not far from Salona, surrounded by a fast-moving stream.175 All attempts by Tiberius to capture it by direct means had so far failed. Anticipating a siege, Bato had wisely stocked provisions there; he could endure a blockade for some considerable time – time that Tiberius did not have. When the Romans tried to scale or undermine the walls, the defenders pelted his men with rocks and projectiles, and launched hit-and-run raids on his wagon trains carrying essential supplies. ‘Hence Tiberius,’ writes Dio, ‘though supposed to be besieging them, was himself placed in the position of a besieged force.’176

The odds of a successful counteroffensive to reduce Andetrium gradually turned in the Romans’ favour. They had clear superiority over the rebels in one key respect: supply chain management. Able to draw upon the resources of the empire during the last winter, the Romans had replenished their combat units’ stocks of food and matériel, though the supply of grain remained an ongoing issue.177 In contrast, the years of war had taken its toll on the rebels. Unable to tend to their fields, beyond the special arrangements Bato had made at fort Andetrium, the rest of the rebel army, lacking food and the means to treat wounds, went hungry and many succumbed to disease.178 Fear also permeated their ranks. Were they to surrender, these deserters from the auxiliary units of the Roman army could not expect to be shown mercy by the Romans; they saw to it that those intent on laying down their arms – such as one Scenobardus – were prevented from doing so.179

Encamped in his praetorium tent on the plain beneath the walls of Andetrium, Tiberius was deeply frustrated. Incensed at their commander’s apparent indecision, his troops were rioting and shouting protests loudly. The commander needed to contain the unrest, and quickly reassert his authority. Yet it was against his nature to make rash decisions. He was, above all, a strict disciplinarian. He mustered the men. From a tribunal he addressed them, rebuking some, but staying calm as he delivered his speech.180 Bato heard the noise and, from his place on the parapet, watched the Roman army standing to attention before its commander with growing unease. He feared an imminent attack and ordered his men to retreat into their fort for safety.181 He dispatched a herald to Tiberius with a request for terms.182 The Roman commander now had the rebel leader exactly where he wanted him. Yet Tiberius would not negotiate with the rebel leader and, instead, rallied his men for a direct attack on the fort.183 Bato had correctly read his adversary’s intentions.

The legionaries formed up in their centuries and cohorts. Arrayed in a quadratum (a dense square or rectangle formation), his men advanced towards the fort. At first they marched at a steady walking pace, and then, as they approached the walls, picked up speed into a trot, breaking into a charge only when they reached the rocky ascent. The rebel soldiers deployed outside the walls rained down missiles upon the advancing Romans – Dio lists rocks, slingshot, wagon wheels, carts and circular chests loaded with rocks.184 For a while it seemed the rebels were winning, and the men watching the battle from the top of the circuit wall cheered on their side. The Romans sustained casualties, but for Tiberius it was a calculated risk, and he now sent up reinforcements.185 Seeing the addition of new troops, the insurgents panicked. In the chaos of battle, the rebels inside closed the gates of the fort; many still fighting outside now discovered they could not retreat to safety.186 In desperation they tried to escape up the mountainside, throwing down their cumbersome weapons and shields. The Romans continued their relentless chase into the forests. When the soldiers found the enemy, they slew them like hunted prey.187 Witnessing the fate of their kinsmen and assessing the situation to be hopeless, the men inside Andetrium capitulated. In the confusion Bato escaped. Disappointed that he had not captured his opponent, Tiberius spent the days immediately after the siege in arranging the affairs concerning those who had surrendered to him.188

| C. Poppaeus Q. f. Sabinus | Q. Sulpicius Q. f. Camerinus | |

| suff. | M. Papius M. f. Mutilus | C. Poppaeus Q. f. Secundus |

On New Year’s Day, the ‘imperium of the Roman People’ was at its greatest extent (map 23). In the forty years since Actium, Augustus and his team of commanders had added nearly double the territory of the empire. Yet problems remained within its extended borders and the legions were arranged in strategic clusters rather than strung along the frontier (table 3).

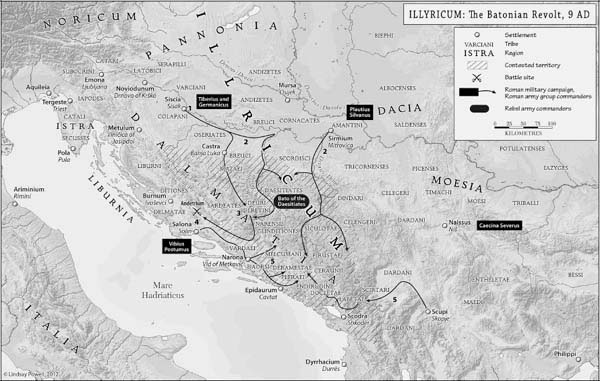

Having demonstrated success in command, Germanicus Caesar now took a prominent role in the prosecution of the war against the remaining rebels in Illyricum (map 24).189 He laid siege to an important stronghold called Arduba.190 There Germanicus’ army faced defenders protected within thick stone walls surrounded almost entirely by a fast-flowing river.191 Faced with this seemingly impregnable fortress, his numbers, which were greater than those of the besieged, did not give him any tactical advantage. It was the people inside Arduba who, unexpectedly, tipped the odds in his favour. Many desperately wanted to surrender and avoid an uncertain fate. Their anguished pleas were spurned by women loyal to the rebellion, who swore liberty or death over surrender and ignominy. Those trying to escape were obstructed by others determined to remain inside. Fighting broke out among the two opposing sides. Some escapees reached the Roman line and offered their unconditional surrender, but those still in the town chose to end their lives, either throwing themselves onto bonfires or hurling themselves into the river.192 Satisfied the siege was over, Germanicus put Postumius in charge of mopping-up operations and left to rejoin his adoptive father.193 Learning the fate of Arduba, other strongholds still in rebel hands promptly offered their own surrender.

Table 3. Dispositions of the Legions, Summer 9 CE (Conjectural).

| Province | Units | Legions |

| Hispania Tarraconensis | 4 | II Augusta, IV Macedonica, VI Victrix, X Gemina |

| Germania | 8 | I Germanica, V Alaudae, XIII Gemina, XIV Gemina, XVI Gallica, XVII, XIIX, XIX |

| Pannonia | 4 | VIII Augusta, VIIII Hispana, XV Apollinaris, XX Valeria Victrix |

| Dalmatia | 2 | VII Macedonica, XI |

| Moesia | 2 | IV Scythica, V Macedonica |

| Syria | 4 | III Gallica, VI Ferrata, X (Fretensis), XII Fulminata |

| Aegyptus | 2 | III Cyrenaica, XXII Deiotariana |

| Africa | 1 | III Augusta |

Sources: Appendix 3; Hardy (1889), p. 630; Lendering (Livius.org); Syme (1933 and 1986).

Bato was still free and negotiating terms with Tiberius.194 Bato sent his son Sceuas with an offer of surrender in exchange for a pardon. This time Tiberius agreed.195 It seems he had learned from previous failures of post-war policy in Illyricum following the Bellum Pannonicum.196 On a late summer evening, Bato set off for the Roman camp. On his arrival next morning, he was taken under armed escort and presented before Tiberius as the assembled Roman troops watched. But Bato surprised his captors. He now displayed the courage and dignity the Romans respected in a defeated enemy. He kneeled before the Roman commander, who was seated upon a tribunal, and laid down his arms at his feet; he spoke in defence of his fellow rebels, pleaded for clemency for his men, but asked no special treatment for himself.197 Bowing his head, he bared his neck ready for the coup-de-grâce. The order was stayed. Germanicus declared victory for the Romans, and the troops vociferously acclaimed Tiberius – shouting ‘Imperator!’ – for his achievement; it was his sixth accolade. The long and brutal ‘War of the Batos’ was finally over.

Map 23. Roman Empire, 9 CE.

Map 24. Military operations in Illyricum, 9 CE.

Receiving the news in Rome, some senators were eager to award Tiberius a new and distinctive accolade. Among the titles proposed were Pannonicus (‘Conqueror of Pannonia’), Invinctus (‘Invincible’) and Pius (‘Pious’); all were overruled by Augustus.198 A triumph would be adequate reward, he said.199 Moreover, it would be shared by his subordinates who had shown valour during the four-year-long campaign.200 As for Bato, he would be exhibited as a human trophy during the celebration for the amusement of the Roman People lining the procession route.

While the Romans celebrated the end of rebellion in the Western Balkans, they were taken by complete and utter surprise by the start of a new one in the lands across the Rhine River they thought pacified.201 The ringleader of the German rebellion was Arminius, a hostage from 7 BCE who, after being taken to Rome, had been promoted into the Ordo Equester and given command of his own unit of Cherusci nationals, perhaps seeing service in the Western Balkans.202 His motives are unclear. Roman authors speculated that to Arminius it may have appeared that if the Romans could oppress the people of Illyricum through the imposition of tribute and taxes, and commit abuses while collecting them, they could – and likely would – do so in Germania; there could be no end to Roman tyranny as long as they were in his country. In his conspiracy he was assisted by his father Segimerus (or Sigimer).203 Together they secretly assembled an alliance of several Germanic nations – among them the Angrivarii, Bructeri and Marsi. They agreed a plan to destroy the Roman army as it passed through their lands en route to its winter camps along the Lippe and Rhine rivers. How many men Arminius’ alliance was able to put into the field is not recorded, but one reasoned, conservative estimate is 15,000 men.204

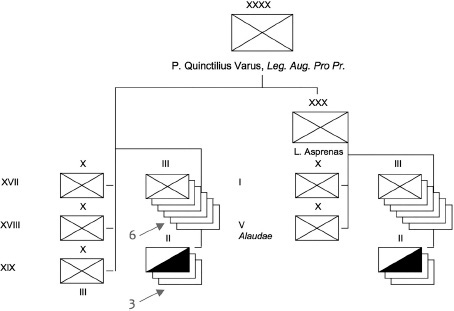

His summer campaign concluded, Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore P. Quinctilius Varus ordered his army to return home. He had with him three legions, three alae of cavalry and six cohortes of auxiliaries205 (see Order of Battle 4). At full strength that would represent 22,752 men at arms; however, the force was likely significantly smaller, perhaps as few as 14,000 men.206 It was no small force to defeat but, as the Germans had seen on several previous occasions, including Arbalo in

11 BCE, the Roman army was most vulnerable on the march.207 In his favour, Arminius could count on the trust and complacency of the Roman commander, which he and his complicit father had carefully nurtured in recent days.208 As far as Varus was concerned, Germania was at peace. So convinced was he of it that when informed by Segestes – ‘a loyal man of that race and of illustrious name’ and Arminius’ father-in-law – about the conspiracy he chose to ignore the warning.209 Reassured, Arminius could move forward with his plot.

On a predetermined date, Varus received a report of ‘an uprising, first on the part of those who lived at a distance from him’.210 Then, as the Roman column marched out from its summer camp, Arminius rode up to Varus with a request to excuse his ala, giving as his reason the need to ride ahead to assemble their allied forces.211 Varus agreed. The column moved on. In his account of the battle, Dio criticizes Varus for poorly organizing his column and baggage train.212 Normally non-combatants would follow the army, but, he says, traders, slaves, women, children and the wagons were mixed up with his troops and arranged in no particular order.213 Ahead lay uncharted territory and there was no road to lead them through it.214 In Tacitus’ account (and only his), the region of hills and forests is called Saltus Teutoburgiensis – located perhaps in the vicinity of Kalkriese near modern Osnabrück, though there are several other candidates.215 Legionaries in the vanguard had to fell trees to clear a way forward and erect simple bridges over rivers too deep to cross by foot. Late in the afternoon, the men established a camp for the night for their comrades arriving at the end of their march.

Order of Battle 4. Germania, 9 CE. In addition to two legions, Asprenas had an unknown number of ethnic auxilia, alae and cohortes under his direct command.

At dawn the following day, the reveille sounded, the troops awoke, ate, kitted up and broke camp. Varus had yet to receive word from Arminius and his Cherusci auxiliaries, but he was not unduly worried. Unbeknownst to the commander, the Germans had slaughtered the Roman soldiers billeted at the road stations and staging posts embedded in their communities.216 The warriors of the Germanic alliance then assembled at their designated places along the anticipated route of the Roman soldiers’ march and waited, hidden among the trees and undergrowth, ready to strike.217 That afternoon, exploiting the element of surprise, they launched an enfilade of frameae and stones upon the unsuspecting legionaries and non-Germanic auxiliaries.218 The Germans rushed upon the Romans in their disorganized line. Some swung their long spears in a menacing wide arc like a scythe to cut at legs and ankles, while others used theirs to thrust and stab, forcing their opponents to step back to avoid the deadly blows.219 Other German warriors wielded single-edged iron swords, which they used to slash and chop their opponents’ unprotected arms and legs. Finding themselves attacked, the unarmed civilians sought what cover they could find amidst the unfolding terror. The infamous Battle of Teutoburg Pass – also known as Teutoburg Forest – had begun.

Arminius’ rebels now sealed off Varus’ escape route, leaving him only one direction of travel: forward and deeper into their trap.220 The legionaries attempted to defend themselves and stand their ground. Those that could threw their pila and formed up with their gladii drawn, gripped close to their bodies, and their shields held high so that only their eyes were visible. Their armed resistance became harder when, according to Cassius Dio, a strong wind blew up and it began to rain heavily.221 Roman troops and their equipment quickly became sodden. The soldiers struggled to hold their scuta steady, made heavier by the rain-soaked protective leather covers (sarcinae), as the wind buffeted them like kites. The Romans took casualties while inflicting few in return.222

Varus ordered a camp to be pitched. Scouts identified a clearing on a rise among the trees.223 While some troops dug with their entrenching tools, others fought, all of them operating under a constant hail of slingshot and spears.224 Almost as suddenly as it had started, the German attack ceased. Relieved, the Romans filed in behind their hastily dug entrenchments, which were large enough for all three legions.225 In his praetorium tent, the senior officers met with Varus that evening. Arminius was still absent, presumed delayed by rebels or missing in action.

At dawn on the third day of the German revolt, the Romans evacuated their camp, intent on getting some distance between them and the enemy’s forces.226 The priority was to reach the fort called Aliso as fast as possible. Varus ordered the wagons to be burned and to leave behind any impedimenta that could not be destroyed.227 The unencumbered army emerged out of the forest into open country. But the Germans were waiting for them and attacked anew. They maintained their assault throughout the day. Varus’ men reached the end of the open plain. Ahead of them was more dense forest. Their only choice was to enter it. Germanic warriors lay in wait to attack them once within. The legionaries and auxiliary infantry tried to form up, but in the confined spaces between the trees their own cavalry only hampered their manoeuvres.228 Without supplies and entrenching tools, the men tried to establish a defensible space as best they could. Varus and his officers assessed their desperate situation. L. Eggius, one of the praefecti castrorum, proposed surrender, but he was pointedly overruled.229

The fourth day began with more heavy rain and a gale-force wind.230 Now lost deep inside the territory of the Bructeri, the soaked and exhausted Roman troops came under attack once more.231 In the ensuing struggle Eggius fell.232 Perhaps on this day too 53-year-old centurion M. Caelius of Legio XIIX perished.233 The contemporary general-turned-historian Paterculus records how Numonius Vala, legatus of one of the three legions, attempted to break out with his scouts; he and his men were surrounded by Germans and cut down.234 He also cites one Caldus Caelius, who, having been taken captive and realizing the terrible fate that awaited him, used the prisoner’s iron chain around his neck to strike a fatal blow to his head.235 Legionary standard bearer Arrius is reported as having grabbed the aquila from off its pole to avert the disgrace of it falling into the enemy’s hands.236 Tucking the venerated eagle into his tunic, he managed to hide in a marsh for a while before finally being discovered.237 One officer, Ceionius, believing he might be shown mercy by his captors, surrendered; his fate is not recorded, but blood offerings and human sacrifice were widely practised among the Germanic peoples.238 Florus preserves the story of one legionary who, having had his tongue cut out, saw it waved in front of him by the German torturer. ‘At last, you viper,’ the German is alleged to have said, ‘you have ceased to hiss.’239 The victim’s lips were then sewn together.

Seeing all was lost, Varus committed suicide along with many of his deputies.240 To prevent its desecration, Varus’ adjutants attempted to burn their commander’s body, but they only partially succeeded. The Germans found the charred corpse, cut off the head and presented it to Arminius.241 He sent it to Marboduus of the Marcomanni, hoping he would join the cause and declare war on the Romans. However, the king remained true to the treaty he had signed with Tiberius. He sent the head to Augustus.242 The war spoils were divided among the rebel alliance partners. The prized aquila of Legio XIX went to the Bructeri, with the other two given to the Chauci and Marsi.243

Remarkably, despite the relentless onslaught, there were survivors. Many were enslaved by their Germanic captors, but some had their eyes gouged out or hands cut off.244 The Germans quickly occupied all of the Roman installations across the country – all but one: Aliso.245 There the Praefectus Castrorum (or Primuspilus) L. Caecidius opened the gates to refugees while using archers to prevent the enemy from coming too close to the perimeter wall.246 Surrounded by German rebels, the people inside, hoping relief would come, were now trapped.247 The besiegers set up pickets on the military road along the Lippe to the Rhine to stop anyone who might try to escape. Caecidius conceived clever ruses to deceive the Germans and to buy more time for his few armed men and many frightened civilian guests.248 Concerned that the Germans might take the stacks of wood his soldiers had stocked outside the wall and use it to set fire to his fort, he dispatched his men in different directions; they pretended to search for fuel, while actually retrieving the timber before it could fall into enemy hands.249 Faced with dwindling supplies, he tried to convince the Germans that the Romans had sufficient food to withstand a blockade:

They spent an entire night leading prisoners round their store-houses; then, having cut off their hands, they turned them loose. These men persuaded the besieging force to cherish no hope of an early reduction of the Romans by starvation, since they had an abundance of food supplies.250

When a storm blew up a few nights later, Caecidius seized the opportunity and led the people out of the camp.251 Now beyond the perimeter wall, the anxious escapees faced great dangers:

They succeeded in getting past the foe’s first and second outposts, but when they reached the third, they were discovered, for the women and children, by reason of their fatigue and fear as well as on account of the darkness and cold, kept calling to the warriors to come back.252

Instead of pursuing them, however, the Germans stayed and plundered the abandoned fort.253 Their distraction allowed the fittest Romans to get some distance away. The horn-players with them sounded the signal for a march at plenus gradus (‘full step’), causing the enemy to think that relief troops were on their way. Through his cunning and courageous actions, Caecidius won ‘with the sword’ the safe return of the refugees to the winter camps on the Rhine.254 Coming to their aid was Varus’ nephew, L. Nonius Asprenas.255 His timely intervention also prevented other German tribes, who were wavering in their loyalty, from defecting to Arminius’ side.256 The former suffect consul of 6 CE still commanded Legiones I and V Alaudae – the only two legions now standing between the Germanic rebels and the Roman homeland.

News of the loss of three legions and the hurried evacuation of Germania reached Tiberius by messenger just five days later.257 Arriving at Ara Ubiorum, Tiberius quickly ordered guard details to be posted along the bank of the Rhine to intercept any German invaders attempting a crossing.258 Deputising Germanicus as commander on the frontier, Tiberius rode off to Rome to determine with Augustus what to do next.

When Augustus was informed of the calamity, his reaction was one of shock and dismay. His worst fears had been realized. He is reported to have torn at his clothes and exclaimed: ‘Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions!’259 Fearing his German bodyguard might turn on him, he dispatched the Germani Corporis Custodes ‘to certain islands’ where they could do him no harm, and required ‘those not under arms to leave the city’.260 His reaction was driven, according to one source:

not only because of the soldiers who had been lost, but also because of his fear for the Germanic and Gallic provinces, and particularly because he expected that the enemy would march against Italia and against Rome itself.261

He also took the additional precaution of extending the terms of the provincial governors to ensure the allies continued to work with men they knew and remained loyal.262

News of the catastrophe – which rapidly acquired the moniker Clades Variana, the ‘Varian Disaster’ – spread far and wide, and terror of barbarians of all kinds gripped the population of Rome. Augustus ordered the Cohortes Urbanae to maintain patrols (excubiae) throughout the city during the night to reassure the city dwellers and to prevent any unrest.263 Illustrating how grave the public perceived the situation, even the religious festivals were temporarily suspended.264 However, Augustus solemnly vowed to hold games to Iupiter Optimus Maximus in return for his help to avert the dire situation facing the Res Publica.265

When Tiberius reached Rome, he decided not to celebrate his full triumph but, nevertheless, insisted on wearing the embroidered purple garments of the triumphator.266 Tiberius ascended a tribunal erected in the Forum Romanum and took his place beside Augustus, sitting between the two consuls, while the members of the Senate stood alongside. Tiberius addressed the assembled crowd with carefully chosen words. He was then escorted to pay the required religious observances at the Capitolium. It was a public display of solidarity between Augustus and his most senior field commander, and also a reminder to the people that despite a military setback, the pax deorum – the sacred pact between the Roman state and its gods – still prevailed.267

The urgent need was to boost the drastically reduced numbers of troops on the Rhine, now Rome’s de facto border in the north. Having already conscripted men of military age to fight in Illyricum just three years before, there were fewer available this time who could be called up to defend the Fatherland.268 Nevertheless, he issued instructions for a another dilectus ingenuorum to fill the ranks of new volunteer cohorts. His call to action met with passive resistance:

When no men of military age showed a willingness to be enrolled, he made them draw lots, depriving of his property and disfranchising every fifth man of those still under 35 years of age and every tenth man among those who had passed that age. Finally, as a great many paid no heed to him even then, he put some to death. He chose by lot as many as he could of those who had already completed their term of service and of the freedmen, and after enrolling them sent them in haste with Tiberius into the province of Germania.269

Ever the disciplinarian, faced with a particularly recalcitrant equestrian who had chopped off his two young sons’ thumbs so that they could not hold a weapon, it is reported that a furious Augustus confiscated the man’s estate and sold it, along with the former owner, at auction.270

As soon as the fresh units of Cohortes Voluntariorum were trained and ready, they would accompany Augustus’ most trusted commander and join his grandson.271 But so shaken by the dire turn of events was Augustus, who was normally fastidious about his appearance, that he did not shave or cut his hair for months.272 Every year thereafter he would mark the anniversary of the disaster at Saltus Teutoburgiensis as a day of sorrow and mourning.273 Yet, despite the calamity, still loyal to his deputy, Augustus honoured Varus by arranging the burial of his head in the tomb of his family.274

| P. Cornelius P. f. Dolabella | C. Iunius C. f. Silanus | |

| suff. | Ser. Cornelius Cn. f. Lentulus Maluginensis | Q. Iunius C. f. Blaesus |