The nationalized army of Augustus comprised legions, auxiliary units, volunteer corps and several fleets, as well as personal bodyguards, an urban paramilitary police force and firefighters, altogether representing 225,000–300,000 men.

1. Personal Bodyguard (Germani Corporis Custodes)

There were several attempts to assassinate Augustus during his lifetime. To foil them, Augustus employed investigators (speculatores). He appreciated their service: ‘Augustus himself writes that he once entertained a man at whose villa he used to stop, who had been his speculator’ (Suet., Div. Aug. 74).

He also employed armed guards. Hired non-Roman troops were highly valued as bodyguards by affluent individuals during the late first century BCE. The Statilii family had as many as 130 Germans in their employ (ILS 7448 f.). Iulius Caesar had a unit of 900 Gallic cavalry (Caes., Bell. Civ. 1.41), as well as Germanic (perhaps Suebic) cavalry (Caes., Bell. Gall. 7.13.1, 67.5, 70.2–7, 80.6) while on campaign. Augustus kept a personal armed troop of foreign mercenaries (e.g. Pliny the Elder, Nat. Hist. 7.46, Dio 54.3.4). Initially he employed a unit recruited from the Calagurritani of Hispania Taraconnensis until the time M. Antonius was overthrown (Suet., Div. Iul. 86.1, Div. Aug. 49.1; cf. Appian, Bell. Civ. 2.109). It was then replaced by the Germani Corporis Custodes. Comprised of Germanic horsemen, they were recruited among the Batavi (Dio 55.24.7) – considered the finest horsemen of their day – and the Ubii. Augustus retained the Custodes until the defeat of Varus (Suet. Div. Aug. 49.1), temporarily removing them from Rome until the emergency ended (Dio 56.23.4). They returned to service in 14 CE (Tac., Ann. 1.24.2, cf. Suet., Galba 12.2). They were later reconstituted as an élite unit of imperial household cavalry, known as Equites Singulares Augusti. For a discussion, see Speidel (1994).

2. Praetorian Guard (Cohortes Praetoriae)

From the earliest times, a unit of élite troops accompanied the praetor or commander of the Roman army on campaign (Sallust, Cat. 60; Cic., Cat. 11; Caes. Bell. Gall. 1.40; Livy, 2.20; Appian, Bell. Civ. 3.67, 5.3). In 49 BCE, Iulius Caesar had a cohors praetoria caetratorum, a bodyguard of Spanish shield-men (Caes., Bell. Civ. 1.75) in his service. After Actium (31 BCE), Caesar’s heir had five Cohortes Praetoriae, which he had recruited from evocati, legionaries recalled to the standards (Orosius 6.19.8; App., Bell. Civ. 3.66, 69), who marched under a single ensign (App., Bell Civ. 3.40). He combined them with M. Antonius’ three Praetorian Cohorts (App., Bell. Civ. 3.45, 3.67), increasing the total number to nine – numbered I through to VIIII – by the close of his principate, and established them as a separate force (Tac., Ann. 4.5.3). Augustus allowed no more than three (each of perhaps up to 1,000 men) to be billeted in Rome at any one time (Suet., Div. Aug. 49; cf. Tib. 37). They were scattered throughout the city (Tac., Ann. 4.2.1), the rest being located around Italy (Suet. Div. Aug. 49; Paullus Dig. 1.15.3 pr) – perhaps at Aquileia, Ariminum, Brundisium, Ravenna and Ticinum, where Augustus was a regular visitor – eventually becoming a force 10,000-strong (Dio 55.24.6). Praetoriani were recruited from men of Etruria, Latium, Umbria and the old Italian coloniae (Tac., Ann. 4.5). Each cohort had its own tribunus, but in 2 BCE they were brought under the overall command of two senior equestrian praefecti praetorio, known by name as Q. Ostorius Scapula and

P. Salvius Aper (Dio 55.10.10); they were succeeded sometime in or before 14 CE by P. Valerius Ligur (Dio 60.23.2) alone or jointly with L. Seius Strabo.

The primary function of the Praetorian Cohorts was to provide the princeps with a guard detail while in the city – Augustus personally gave the daily watchword to the contingent on duty at his home on the Palatinus (Tac., Ann. 1.7.5) – and when he was on campaign. They also accompanied him on trips, which he often did in a litter by night or by sea (Suet., Div. Aug. 53.2, 82.1), as well as members of his family on missions when two cohorts were usually despatched (Tac., Ann. 1.24.2 and 2.20). They may also have been assigned to other duties ad hoc. There is evidence that Praetoriani of Cohors VI were despatched to fight a fire at Ostia – perhaps to supplement the beleaguered civilians in the port city – since one soldier is recorded as having perished in the attempt and was buried with a public funeral in the Augustan period (CIL XIV, 4494 = ILS 9494 = EJ 252). In addition to infantry there was Praetorian cavalry, which rode with the militia equestris at a decursio during Augustus’ funeral in 14 CE (Dio 56.42.2; Tac., Ann. 1.24.2).

Keen to secure the loyalty of the men, Augustus’ first act of 28 BCE was to raise their pay to double that of regular legionaries ‘so that he might be strictly guarded’ (Dio 53.11.5). A guardsman received 2 denarii per day, or HS3,000 annually (Tac., Ann. 1.17). His term of service was originally sixteen years, then reduced to twelve in 14 BCE (Dio 54.25.6), but raised to sixteen again under Augustus’ military reforms in 5 CE (Dio 55.23.1). Upon honourable discharge, each retiree received a cash bonus (praemia) of HS20,000 (or nearly seven years’ pay) – HS8,000 more than regular legionaries (Dio 55.23.1; Tac., Ann. 1.17). The men of the Praetorian Cohorts each received HS1,000 from the estate of the deceased princeps – more than three times that paid to regular legionaries (Suet., Div. Aug. 101.2). Forty Praetoriani had the honour of carrying the body of Augustus to lay it in state (Suet., Div. Aug. 99.2).

For detailed discussions, see Allen (1908), Bingham (1997), Daugherty (1992), Durry (1938) and Rankov (1994).

3. Citizen Army (Legiones)

After the Civil War (31–30 BCE), some fifty to sixty legions of varying strengths were in existence. Three years later, Augustus had dissolved almost half of the legions and demobbed around 120,000 men (RG, 15; Dio 55.23.7). Before the Varian Disaster (9 CE), there were twenty-eight legions, after it twenty-five, each nominally 6,200 men strong (Festus 453 L), though in practice likely fewer – perhaps 5,280 soldiers per legion – so the available army at full strength including officers was between 140,000 and 174,000 men.

Every legion had an index number to identify it, though as a result of the rationalization and consolidation of units some numbers appeared twice. Many legions had a title (agnomen), awarded either for victory in battle denoting where it was won (e.g. XI Actiaca, VIIII Hispana), or indicating its origin (e.g. X Gemina, ‘twin’ from merging two legions into one: Caes., Bell. Civ. 3.4.), or recognizing an honour personally awarded by Augustus (e.g. II Augusta, ‘Second Augustus’ Own’: Dio 54.11.5).

Commanding the legion (from legere, meaning ‘to choose’) was the legatus legionis, a man appointed by Augustus from the patrician class, nobiles or novi homines (e.g. P. Quinctilius Varus of Legio XIX in 15 BCE; Sex. Vistilius: Tac., Ann. 6.9; Numonius Vala in 9 CE: Vell. Pat. 2.119.4). He was usually an expraetor, but he could be an ex-quaestor, ex-aedile or ex-plebeian tribune. A man in his forties, he would typically serve for one to three years. A unit (ala) of 120 mounted legionaries (equites legionis) provided an escort for the legatus as well as a messenger service for him and his staff.

Assisting the legate was a military tribune (tribunus militum) ‘with the broad stripe’ (tribunus laticlavius) and five junior tribunes with ‘narrow stripe’ (tribuni angusticlavi), who were appointed from the ordo equester. Iulius Caesar was generally disappointed by the quality of these officers (Caes., Bell. Gall. 1.39); Augustus tried to improve their calibre and, like Caesar, hand-picked them before deployment (Dio 53.15.2). Typically men in their late teens, they served a term of one year: at age 17, Tiberius was a tribunus militum in Hispania Citerior in 25 BCE (Suet., Tib. 9.1), and similarly Velleius Paterculus (Vell. Pat. 2.104.3). The detachments (vexillarii or vexillationes) of Legiones I, V, XX and XXI involved in the punitive raid into Germania in 14 CE were led by a military tribune named Novellius Torquatus Atticus (CIL XIV, 3602 (Tibur) = ILS 950).

Third in the command structure was the camp prefect (praefectus castrorum), a new career position introduced under Augustus, one based on the praefactus fabrum of earlier times. He was responsible for provisioning the legion, managing the camp’s facilities and their security, as well as soldiers’ training and the artillery (e.g. Hostilius Rufus: Obsequens 72; L. Eggius: Vell. Pat, 2.119.4; L. Caecidius: Vell. Pat. 2.120.3). He was recruited from the Ordo Equester.

An aquilifer (e.g. Arrius: Crinagoras, Pal. Ant. 7.741.) carried the most important ensign of the legion – the eagle (aquila) clutching lightning bolts in its talons, the symbol of Jupiter – on a pole. To lose it was a shameful act (infamia), and for this reason the Clades Lolliana of 17 BCE and Clades Variana of 9 CE caused Augustus great embarrassment (Suet., Div. Aug. 23.1).

The basic tactical unit of the legion was the cohort (cohors); ten cohortes (numbered I through to X), representing some 480 men each, formed a legion, the first being of double size (960) – thus the legion at full strength would field 5,280 soldiers. A cohort comprised six centuries (centuriae) of up to 80 men under the command of a centurio (e.g. M. Caelius, Legio XIX: CIL XIII, 8648; Canidius: Florus 2.26). The century consisted of ten contubernia of eight men messing together.

A centurion could be appointed from the Ordo Equester or promoted from the ranks of the ordinary men after having proved his leadership skills and courage. Aufidienus Rufus began his career as an ordinary soldier, serving in that capacity for several years, followed by promotion to centurion, culminating in his appointment as praefectus castrorum of one of the Danube legions, where he is recorded in 14 CE (Tac., Ann.1.20). The centurio was distinguished from the rank and file by the transverse crest on his helmet. He carried a vine staff (vitis), which he used for casual corporal punishment, such as used by Lucilius – targeted by the mutineers of AD 14 – ‘to whom, with soldiers’ humour, they had given the name ‘‘Bring Another’’ [cedo alteram], because when he had broken one vine-stick on a man’s back, he would call in a loud voice for another and another’ (Tac., Ann. 1.23). The mental toughness of centurions is frequently described in the ancient sources (e.g. Maevius’ defiance before M. Antonius in 30 BCE, Val. Max. 3.8.8).

Assisting the centurion was his personally appointed deputy (optio) and a man (tesserarius) designated for issuing the writing tablets containing the watchword; a standard bearer (signifer, e.g. Q. Coelius Actiacus of Legio XI: CIL V, 2503 (Ateste)) and a horn player (cornicen), who together relayed orders on the battlefield. The centurion of the First Cohort was the Primuspilus and, by rank, the most senior centurion of the entire legion. The career of M. Vergilius Gallus Lusius included a stint as primuspilus with Legio XI before a promotion to Praefectus Cohortis with Cohors I Ubiorum peditum et equitum (CIL X, 4862 (Venafrum) = ILS 2690). In general, the men advancing beyond the rank of primuspilus were officers who began their career as centurions, and in exceptional cases were soldiers of the Praetorian Cohorts who had been promoted to the centurionate.

A free-born, healthy man of minimum age of 16 or 17 was eligible to enlist as a legionary soldier (miles gregarius), nicknamed a caligatus. The names of many survive, and occasionally details of their careers: e.g. M. Billienus Actiacus of Legio XI who fought at Actium (ILS 2443); L. Plinius of Legio XX (ILS 2270); Caelius Caldus (Vell. Pat. 2.120.6); M. Aius, serving in the centuria of Fabricius (Kalkriese); and T. Vibus, centuria of Tadius (Kalkriese). In Augustus’ time, most came from the coloniae and municipia of Italia and Gallia Cisalpinia. Increasingly, the ranks of caligati were supplemented by provincial recruits from Narbonensis, the Tres Galliae and the Hispaniae. A legionary was contracted to serve for sixteen years (Tac. Ann. 1.19), but the term of service was raised to twenty years after 5 CE (Dio 55.23.1, 57.6.5). Training was intense, physical and comprehensive. A team of specialists covered drill, formation fighting, swordsmanship, archery, horse riding, swimming, route marches, camp building and leaping over ditches in full kit (Veg., 1.9–28). He was expected to march 20 miles in five hours on a day in summer at normal ‘military step’ (militaris gradus), but in wartime a forced march (magna itinera) at the swifter ‘full step’ (plenus gradus) could increase this to 24 miles (Veg. 1.9).

A legionary was equipped with a full array of protective kit (armatura). Archaeological finds attest to there being a continuous process of innovation in design of equipment during the Augustan period, perhaps driven by the exigencies of local warfare. A large oval shield (scutum), made from thin sheets of wood laminated into a kind of plywood, curved to protect the body and held by a central hand grip (umbo), evolved into a wider, squarer shape. On the march, the shield was usually protected by a cover of stitched leather or goatskin. The head protection (casis, galea) featured an integral neck guard and articulated cheek plates (bucculae) tied at the chin. Its design changed from the conical – so-called Montefortino – helmet made of bronze in widespread use in 31 BCE; to the ‘jockey-cap’ style – or Coolus – helmet with a separate eye/brow guard to deflect blows to the face, and a wider neck guard; and finally into the so-called Weisenau (or ‘Imperial Gallic A’ type according to Robinson’s (1975) classification), made of iron with detailing at the front and back to strengthen the dome. Body armour of a shirt of riveted links (lorica hamata) or scales (lorica squamata) may have been worn over an arming doublet of linen or leather with a decorative fringe (pteryges) to allow for greater movement. From c. 15 BCE, a new form of articulated, segmented plate armour (the so-called lorica segmentata) was introduced; finds from Dangstettten and Kalkriese show conclusively it was worn by some troops in the Alpine and German Wars. A heavy leather belt, with a sporran (cingulum) covered with bronze discs or plates to protect the genitals, completed the panoply.

His weaponry consisted of two javelins (pila), each made with an iron shank attached with a pin to a wooden shaft designed to break on impact so that it could not be thrown back (Plut., Mar. 25.1–2; Caes., Bell. Gall. 1.25); a short, doubleedged sword tapering to a sharp point (gladius) for cutting and thrusting; and a short dagger (pugio) as a sidearm of last resort. Finds from Haltern, Hedemünden, Kalkriese, Mainz, Mannheim, Nauportus, Nijmegen and Oberaden reveal variations in design in the same type of equipment. Soldiers often paid to have their kit – belts, daggers and scabbards in particular – decorated with engravings and coloured inlays to very high standards of workmanship to make them unique, personal pieces. Thus there was little uniformity in the appearance of troops in combat gear, even in an individual centuria.

Additionally, soldiers carried an entrenching tool (dolabra) – combining a pick on one side and a spade on the other – for digging ditches, a saw, a pan (trulla), a length of chain and rope, personal clothing in a bag, all carried on a pole over the left shoulder, and two palisade stakes (sudes) over the right. At the end of a day’s route march, legionaries dug a temporary camp with a ditch and earthen bank (e.g. Dio 56.21.1); those not on watch duty slept in their contubernia in tents (sub pellibus or sub tentoriis) made of goatskin which, when collapsed and packed, were usually transported by a mule or on a wagon; because of its appearance, and the fact it emerged from a rolled-up form, a tent was nicknamed a papilio, ‘butterfly’. A semi-permanent summer camp (castra aestiva) could be erected for campaigning in theatre, such as at Minden. The army might return to a permanent winter base (castra hiberna) with barracks constructed of wood, like Haltern, at the end of the season. At this time, the fort or fortress might be shared – such as at Carnuntum, Nijmegen-Hunerberg and Oberaden, which each likely housed two legions plus auxiliary troops. Great attention was paid to the position and design of defensive fortifications and stockades (e.g. Caes., Bell. Civ. 3.63, 3.66), the erection of which was overseen by the praefectus castrorum.

A legionary could not marry while in service, and if he was already married the act of enlistment was an automatic form of divorce. Centurions and higherranking officers were, however, permitted wives, though their presence in camp was frowned upon except during winter (Suet., Div. Aug. 24.1). All ranks could have slaves or freedmen to assist with handling baggage (impedimenta), minding pack animals, attending to general chores and, on occasions, fighting (Dio 56.20.2, cf. 78.26.5–6; Tac. Ann. 1.23). An inscribed lead disc with a hole in the centre – which may have been a luggage tag – found at Dangstetten reveals that when Quinctilius Varus was legate of Legio XIX there was a lumentarius (a slave for handling baggage) assigned to the First Cohort named Privatus. On the tombstone of centurio M. Caelius, on either side of his image, are the heads of his liberti Privatus and Thiaminus.

On the battlefield, the legion typically deployed in cohorts, formed up in blocks with space in between, arrayed as two (duplex acies) or three rows (triplex duplex) (e.g. Caes., Bell. Civ. 1.83), with cavalry placed on the flanks. To break the enemy line or receive a massed oncoming opponent, the front line would launch volleys of pila, then assume a wedge formation (cuneus) and charge with swords drawn (e.g. Caes., Bell. Gall. 6.40). After engagement, the lines could be rotated, so that fresh troops would move forward to replace tired ones retiring to the rear. If surrounded, the unit could form a defensive square (quadratus) or the so-called ‘tortoise’ (testudo).

Honours were awarded for conspicuous acts of valour (Suet., Div. Aug. 25.3). The centurion primipilus Gallus Lusius cited above received dona militaria of two spears (hastae) without iron heads and a golden crown (corona aurea) in person from Augustus and Tiberius (CIL X, 4862 (Venafrum) = ILS 2690). The corona muralis was awarded to the first man to scale a wall, the corona vallaris for a rampart; both were crowns worn on the head and decorated to simulate the exterior of a defensive fortification. Augustus was himself awarded the corona civica – a wreath of leafy oak twigs for saving the lives of Roman citizens – by the Senate and permitted to display outside his home, the Palatium (Dio 53.16.4; Suet., Calig. 19). L. Antonius Quadratus (CIL V, 4365) was decorated twice by Ti. Caesar; during his career with Legio XX he garnered bangles (armillae), as well as collars (torques) modelled after those worn around the neck by Iron Age ‘Celtic’ warriors, and medals (phalerae), which he proudly wore mounted on a leather harness upon his torso.

At this time, a legionary received 10 asses per day (Tac., Ann. 1.17) – a cup of cheap wine at a bar cost 1 as, a fine quality Falernian 4 asses, a loaf of bread 2 asses (CIL IV, 1679, graffito at the Bar of Hedone or Colepius, Pompeii) – or HS900 annually paid in three lump sums; but there were deductions for the cost of food, clothing and armour, and a contribution to a compulsory savings scheme, leaving the legionary around half his pay to spend in hard cash.

A retiring soldier, or veteranus, received a praemia of HS12,000 (or just over thirteen years’ pay) upon discharge – a full HS8,000 less than the soldier in the Praetorian Cohorts (Dio 55.23.1). Veterani could move to one of the many coloniae founded by Augustus (e.g. twenty-eight alone in Italy: RG 28), as C. Valerius Arsaces of Legio V Alaudae did (CIL IX,1460). Antonius Quadratus mentioned above settled as a veteranus at Brixia (Brescia).

With an honourable discharge (honesta missio), a man could still be recalled by Augustus to the eagles as a reservist (evocatus, meaning ‘invited’) for up to five years:

Augustus began to make a practice of employing from the time when he called again into service against Antonius the troops who had served with his father, and he maintained them afterwards; they constitute even now a special corps, and carry rods, like the centurions (Dio 55.24.8).

Evocati ranked above the serving legionaries, but were excused ordinary fatigue duties and allowed to ride horses on the march (Caes., Bell Gall. 7.65). During the Bellum Batonianum, a large vexillarius of veterans located near Sirmium was wiped out by the Breuci (Vell. Pat., 2.110. 6, cf. Dio 55.32.3–4).

Upon the death of Augustus, the men of the legions each received HS300 from the estate of the deceased princeps (Suet., Div. Aug. 101.2). The mutinies of the legions on the Danube and Rhine rivers in the weeks immediately following the death of Augustus in September 14 CE (Tac., Ann. 1.31–49; Dio 57.3.1–6.5), however, suggest that the retirement process was flawed and open to abuse: afterwards, the disgruntled veterani who had fomented mutiny were redeployed to Raetia on the pretence that the Suebi were planning a raid (Tac., Ann. 1.44).

For detailed – and sometimes contentious – discussions of the evidence for the organization and deployments of legions under Augustus, see Allen (1908); Gilliver (2007); Goldsworthy (1996); Hardy (1887, 1889 and 1920); Keppie (1984 and 1996); Le Bohec (1994); Parker (1928), pp. 72–92; Speidel (1982 and 1992a); Syme (1933); Swan (2004), pp. 158–68; and Tarn (1932). For Augustan/early Imperial legionary arms and armour, see Bishop (2002); Bishop and Coulston (2006), pp. 73–127; D’Amato and Sumner (2009), pp. 63–190; Robinson (1975); and Strassmeir and Gagelman (2011 and 2012). For military bases and fortresses, see Bishop (2012) and von Schnurbein (2000). For military awards, see Maxfield (1981).

The legions known to be in operation under Augustus were:

I Germanica (formerly Augusta?). Likely raised by Iulius Caesar in 48 BCE to fight in his war against rival triumvir Cn. Pompeius Magnus, Legio I is first recorded in action at Dyrrhachium (Durrës) on 10 July of that year (Caes., Bell. Civ 1.27). After the assassination, his heir took command of it, fielding it in his campaign against Sex. Pompeius (App., Bell. Civ. 5.112). It also saw action in the protracted Cantabrian and Asturian War of 29–19 BCE (Dio 53.25.5–8), where it may be the legion recorded as having its agnomen Augustus stripped for indiscipline by M. Agrippa (Dio 54.11.5). Some modern historians interpret this act to mean the legion ceased to be a iusta legio and was disbanded, while others dispute this. In the ensuing drawdown it – or a reconstituted Legio I – may have moved to Aquitania or Celtica, and then served with Tiberius. It received its signa from Tiberius (Tac. Ann. 1.42), perhaps on the occasion of the Alpine War (15 BCE) against the Vindelici. It was then transferred to Gallia Belgica – perhaps stationed at Batavodurum (Nijmegen) in the country of the Batavi nation if a single graffito is authentic – and fought in the German War (12–9 BCE) under Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus; it may have earned the agnomen Germanica there (AE 1976, 515; CIL XII, 2234; Tac. Ann. 1.42). His brother Tiberius included Legio I in the mobilization for the Marcomannic War against Marboduus (6 CE), where it was to march along the Main and Elbe, but after news of the Great Illyrian Revolt arrived, the advance was abandoned and the unit returned to its base on the Rhine. After the Varian Disaster (9 CE), it was based at a winter camp shared with Legio XX in the vicinity of Ara Ubiorum (Cologne), whose Legatus Legionis C. Caetronius in 14 CE reported to Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore A. Caecina Severus of the new military district of Germania Inferior (Tac. Ann. 1.37.3, 1.44), which had been created in the wake of the clades Variana.

II Augusta. Possibly founded as the Legio II Sabina by consul Vibius Pansa from recruits in Italy in 43 BCE (App., Bell. Civ. 3.65), it fought at Philippi (October 42) on the side of the conspirators. It was acquired by the victors of the battle and went to see action under the heir of Iulius Caesar’s heir at Perusia (41 BCE) against L. Antonius. It may have subsequently transferred to Gallia Belgica (where it likely received the title Gallica) and its veterans settled at Arausio (Orange). The legion relocated to Hispania Citerior, where it took part in the Cantabrian and Asturian War (29–19 BCE). The veterans of that campaign helped construct Colonia Iulia Gemella Acci in Hispania Tarraconnensis, though its own veterans settled in Barcino (Barcelona) and Cartenna (Mostaganem) – also called Colonia Augusta Legio Secunda (Pliny the Elder, Nat. Hist. 5.20) – in Mauretania. After the Varian Disaster, it transferred to Mogontiacum (Mainz) in Germania Superior, perhaps in 10 CE (CIL XIII, 7234). For a detailed discussion, see Keppie (2002).

III Augusta. Though it is not documented before 5 CE, Legio III was likely founded by Vibius Pansa in 43 BCE and fought for the conspirators at Philippi in October the following year (App., Bell. Civ. 5.3). After its defeat, it was co-opted and saw action in the war against Sex. Pompeius. From 30 BCE, it was stationed in Africa, though the location of its winter camp within the province often changed. As the local permanent garrison, it may have participated in the Gaetulician War (6–8 CE) under Cossus Cornelius Lentulus (Dio 28.3–4). An inscription on a milestone (ILS 151 = EJ 290) confirms it built the road from Tacapes to its winter camp, possibly at Theveste, in 14 CE.

III Cyrenaica. This legion may have been founded by Aemilius Lepidus, who was triumvir with jurisdiction of Cyrenaica in 36 BCE, or by M. Antonius, who assumed responsibility that same year. It was variously located at Thebes, Bernike in the Thebaïd and Alexandria from 35 BCE, where it shared a winter camp with Legio XXII Deiotariana (Strabo, Geog. 17.12, writing around 21 BCE, mentions one legion ‘is stationed in the city and the others [two] in the country’). It may have been active in the attack on Arabia Felix (Yemen) under equestrian Praefectus Aegypti Aelius Gallus (26–25 BCE); and against Nubia under C. Petronius (24 BCE) and the sack of its capital city, Napata (22 BCE). It is attested by an inscription (EJ 232, AE 1910, 207) at Mons Claudianus (dated to 10 CE). The names of thirty-six legionaries – nine born in Galatia, six in Ancyra, four in Alexandria, and one each in Cyrene, Cyprus and Syria, and one (perhaps from Vercellae) in Italy – recorded as serving with Legio III are found on an inscription at Koptos (Qift in Egypt, CIL III, 6627), dated to Augustus’, or latest Tiberius’, principate. For a detailed discussion, see Sanders (1941).

III Gallica. Iulius Caesar may have raised this legion from veterans in Gallia Comata who had missed Pharsalus on account of sickness (Caes., Bell. Alex. 44.4) and others of the old Legio XV returning to Italy. A Legio III is recorded as having fought at Munda on 17 March 45 BCE (Caes., Bell. Hisp. 30). M. Antonius took this legion to Parthia in 36 BCE (Tac., Hist. 3.24.2). It may have been part of the army accompanying Augustus and Tiberius to Armenia and Parthia in 20 BCE before settling in Syria. In the year Herodes died (4 BCE), under the provincial legate P. Quinctilius Varus, the legion was likely one of the three involved in quelling rebellions of the Jewish messianic claimants Iudas, Simon and Athronges (Joseph., Ant. Iud. 17.10.9). An inscription in Cyprus confirms its agnomen as Gallica (CIL III, 217).

IIII Macedonica. Legio IIII was likely originally raised by Iulius Caesar in 48 BCE to fight in his war against Pompeius Magnus and may have been in action (Caes., Bell. Civ. 3.29.) at Dyrrhachium (Durrës) in the spring of that year. Based in Macedonia, it was to be part of the army group assembling for a major campaign against Parthia, but the operation was cancelled when the dictator was murdered. Transferred to Italy by M. Antonius, the men of the legion switched their allegiance with another legion called Martia to the heir of Iulius Caesar (App., Bell. Civ. 3.45; Cic., Phil. 14.27). It fought at Mutina (Modena) in April 43 BCE, where it was defeated by a Legio V and Martia was destroyed (Cic., Ad Fam. 10.33.4). It saw action at Philippi, and on returning to Italy fought against L. Antonius at Perusia (Perugia), evidence for which are sling bullets (glandes) found at the town. It fought at Actium (31 BCE) and veterans were settled at Firmum Picenum (Fermo), attested by an inscription (Dessau 2340). Two years later it was in Hispania Tarraconnensis (Dessau 2454) as part of the grand army fighting in the Cantabrian and Asturian War (29–19 BCE). Its winter camp from 20–15 BCE was Palencia (Herrera de Pisuerga) and its veterans may have settled at Cuartango. It remained in the Iberian Peninsula for the duration of Augustus’ principate (e.g. RPC 1.319, 1.325). The tombstone of M. Percennius from Philippi, ‘miles’ of ‘Legio IV’ – possibly related to one of the known ringleaders of the 14 CE mutiny – was found at Tilurium (Gardun near Trilj, Croatia; CIL III, 14933).

IIII Scythica. Formed after 42 BCE by M. Antonius, the legion may have taken part in the failed Parthian War (39–36 BCE). It was in Macedonia and Moesia and may have earned its agnomen under the command of M. Licinius Crassus, grandson of the infamous triumvir (Dio 51.23.2–27.3) in the Balkans (29–27 BCE ). It saw action in the war to quell the Great Illyrian Revolt (6–9 CE) under A. Caecina Severus’ leadership (Dio 55.32.3–4n., cf. 29.3n, 30.3–4n). It was likely based at Viminacium (Stari Kostolac in eastern Serbia) on the Danube River.

V Alaudae. Recruited from local non-citizens by Iulius Caesar in Gallia Transalpina in 52 BCE (Caes., Bell. Gall. 5.24), paid for by the commander out of his own funds, it became a iusta legio sometime between 51 and 47 BCE, and its soldiers were later enfranchised (Suet. Caes. 24.2). (The agnomen referred to the pointed helmet or the crest the Gallic warriors wore on their helmets, resembling the tuft of the lark, Alauda cristata (Pliny, Nat. Hist. 11.44).) It may have been at the Siege of Alesia (42 BCE); the legion crossed the Rubicon River with its commander in January 49 BCE and was likely quartered in Apulia (Caes, Bell. Civ. 1.14, 1.18). It saw action at Dyrrhachium (48 BCE), Africa (47 BCE; Caes. Bell. Afr. 1), Thapsus (46 BCE) – where it stood against charging elephants deployed by Caesar’s enemies (Caes. Bell. Afr. 81, 84) – and at Munda (17 March 45 BCE; Caes., Bell. Hisp. 30). After the dictator’s murder, the legion sided with M. Antonius (Cic., Epist. 89) and fought for him at Mutina (43 BCE) against Caesar’s legal heir. When both men reconciled, the legion went on with seven others to Philippi (42 BCE) to exact revenge on the murderers of its founder (App., Bell. Civ. 5.3). It went east with Antonius and may have participated in the failed Parthian War (39–36 BCE; CIL IX, 1460 citing the cognomen of one of its soldiers as Arsaces) and fought on his side at Actium (31 BCE). The victor of the battle removed the legion to join the massed forces battling the Cantabri and Astures (29–19 BCE). Its veterans settled in colonia Augusta Emerita (Mérida) in Lusitania (Dio 53.26.1), founded in 25 BCE. In the ensuing drawdown, the legion transferred to Gallia Belgica. In 17 BCE, under its legatus M. Lollius, Legio V was ambushed by a raiding party of Germans from across the Rhine, who wrenched away its aquila – an event which came to be called the clades Lolliana, ‘Lollian Disaster’ (Vell. Pat. 2.97.1; Dio 54.20.4–6). The eagle was subsequently retrieved (Crin., Anth. Pal. 7.741). After the subsequent clades Variana, the ‘Varian Disaster’ of 9 CE, it was quartered at Vetera (Xanten) – meaning ‘The Old One’ – which it shared with Legio XXI (Tac. Ann. 1.31.3, 1.45.1), and at the time of Augustus’ death in 14 CE reported to A. Caecina Severus, the legatus Augusti pro praetore of the military district of Germania Inferior.

V Macedonica. Likely formed at the time of the Second Triumvirate, the earliest mention of the legion is the foundation of a colonia for it at Berytus (Beirut) in Syria by M. Agrippa in 15 or 14 BCE (Strabo, Geog. 16.2.19). Its history before that event is obscure. It may have been founded by Iulius Caesar – perhaps as Legio V Gallica, whose veterans settled in Antiocheia-in-Pisidia (Dessau 2237, 2238), or as V Urbana, known from Ateste (modern Este, Dessau 2236). Legio V likely fought in the Thracian War (c. 13–11 BCE) under L. Calpurnius Piso, where it may have won its agnomen Macedonica (Dessau 2695) and then returned to Galatia. It was transferred to Oescus (Gigen) in Moesia in 6 CE.

VI Ferrata. Iulius Caesar created the legion in 52 BCE in Gallia Cisalpina for his Gallic War of 58–50 BCE (Caes., Bell. Gall. 8.4). How it earned the agnomen Ferrata (‘ironclad’) is not known. It saw action in the war against Pompeius Magnus, fighting at the battles of Ilerda (summer 49 BCE), Dyrrhachium (early 48 BCE) and Pharsalus (9 August 48 BCE). The legion followed Iulius Caesar to Alexandria (48/47 BCE), turned the odds in his favour at the battle of Zela (2 August 47 BCE) in Pontus and was present at Munda (17 March 45 BCE). Its veterans built Colonia Iulia Paterna Arelatensium Sextanorum (Arles) for their retirement in Gallia Narbonensis. Reconstituted by M. Aemilius Lepidus, who gave it to M. Antonius (43 BCE), Legio VI took part at the Battle of Philippi in October of the following year as one of his eight veteran legions (App., Bell. Civ. 5.3). At the end of the civil war, its veterans were given lands in the colonia of Beneventum (Benevento). M. Antonius transferred the legion to Iudaea, where it assisted Herodes in asserting his claim to the throne (37 BCE), and participated in the failed Parthian War (39–36 BCE). It fought on the losing side during the Actian War (31 BCE). The victor sent it back to Syria, where it would remain until the end of the Empire. In 20 BCE, it accompanied Augustus and Tiberius to Armenia. In the year Herodes died (4 BCE), under the provincial legate P. Quinctilius Varus, the legion was involved in quelling rebellions of the Jewish messianic claimants Iudas, Simon and Athronges (Joseph., Ant. Iud. 17.10.9). The location of its winter camp is uncertain, but may have been in Galilee (RE 12.1591, Tac. Ann. 2.79.2), Raphanaea (Rafniye) or Cyrrhus (Khoros). Veterans were later settled at Ptolemais (Acre).

VI Victrix. When Iulius Caesar’s Legio VI swore its allegiance to M. Antonius following its founder’s assassination, the dictator’s legal heir established his own (41 BCE), perhaps with veterans defecting from the original. The following year it was at the siege of Perusia (40 BCE) fighting for Iulius Caesar’s heir, as attested to finds of sling stones (glandes, CIL XI, 6721, nos. 20–23). In the war against Sex. Pompeius it saw action in Sicily, and in the Actian War it fought against Antonius. The legion was one of the eight taking part in the protracted Cantabrian and Asturian War (29–19 BCE) in the Iberian Peninsula. It remained there for the rest of Augustus’ principate. Veterans of the legion were among the first settlers of the coloniae at Augusta Emerita (Mérida; Dio 53.26.1), Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza) and Corduba (Cordoba). For a detailed discussion, see Grapin (2003).

VII Macedonica. One of the oldest legions of Augustus’ army, it is recorded as serving with Iulius Caesar in the Gallic War (58–50 BCE), during which it played an active role (e.g. Plut. Caes. 2.23, 2.26, 3.7, 4.32, 5.9, 7.62, 8.8). It also fought for him in the war against Pompeius Magnus, fighting at the battles of Ilerda (summer 49 BCE), Dyrrhachium (early 48 BCE) and Pharsalus (9 August 48 BCE). Veterans settling in Italy were recalled to join in Iulius Caesar’s African War (46 BCE), where they fought at Thapsus (Caes. Bell. Afr. 81), before retiring the following year to Capua (Dessau 2225) and Lucca. After the dictator’s murder, many retirees flocked to Iulius Caesar’s heir in the autumn of 44 BCE (Cic., Phil. 11.37), forming a reconstituted Legio VII under the agnomen Paterna (meaning ‘ancestral’). It fought at Mutina (Modena, Cic., Phil. 1.c) in April 43 BCE, saw action at Philippi and on returning to Italy fought against L. Antonius at Perusia (Perugia) in 41 BCE. In 36 BCE, veterans settled in Gallia Narbonnensis, though serving troops likely took part in the war against Sex. Pompeius. It may have played a role in the Actian War (31 BCE). It may have remained in the Balkans before transferring to the province of Galatia-Pamphylia with its creation in c. 25 BCE. Legio VII fought in the Thracian War (c. 13–11 BCE) under L. Calpurnius Piso, where it may have won its agnomen Macedonica (Dessau 2695), and then returned to Galatia. From 7 CE, it returned to the Balkans and took part in the Batonian War (Dio 55.32.3–4n) under Tiberius. After 9 CE, Tilurium (Gardun near Trilj) in Dalmatia became its base (cf. ILS 2280 = EJ 265) – though it possibly shared the fortress at Burnum (Kistanje) with Legio XI – for the duration of Augustus’ principate. Veterans – at least fifteen are known from tombstones – settled at the old Caesarian colonia at Narona (between present day Metković and Vid, Croatia) beside the Neretva River; also at a locality northwest of it known as vicus Scunasticus (where two dedication slabs offering prayers to Divus Augustus and Tiberius have been found: see AE 1950, 44; AIJ 113–14 found between Humac and Ljubuški), Rusazu (AE 1921, 16), Tupusuctu (CIL VIII, 8837) and Saldae (Béjaïa) in Mauretania (CIL VIII, 8931). For a detailed discussion, see Mitchell (1976).

VIII Augusta or Gallica. Legio VIII was one of the oldest legions of Augustus’ army, formed of veterans from Iulius Caesar’s old legion (Cic., Phil. 11.37; App., Bell. Civ. 3.47). Caesar mentions it serving with him in the Gallic War (58–50 BCE) and playing an active role (Caes., Bell. Gall. 2.23, 7.47, 8.8). Initially, its honorary title was Gallica. It fought for him in the war against Pompeius Magnus (Caes., BC 1.18), fighting at the battles of Corfinium (Corfinio) and Brundisium (Brindisi) in 49 BCE, and was based in Apulia. It also saw action at Dyrrhachium (early 48 BCE) and Pharsalus (9 August 48 BCE). Veterans settling in Campania were recalled to join in Iulius Caesar’s African War (46 BCE), seeing action at Thapsus (Caes. Bell. Afr. 81), before retiring the following year to Casilinum near Capua. Rallying to the heir of Iulius Caesar, retirees followed him to Mutina (Modena) in 43 BCE to stand against M. Antonius, for which it earned the agnomen Mutinensis (Dessau 2239), and to Philippi the following year. Legio VIII fought at Perusia (Perugia) against L. Antonius, as sling shot from the site attests. Men of the legion likely fought in the Actian War (31 BCE). Veterans settled at Forum Iulii (Fréjus), which was sometimes called by the alternative name Colonia Octavorum (CIL XII, 38). After 27 BCE, Augustus moved Legio VIII to Africa. A detachment saw service in the Cantabrian and Asturian War (29–19 BCE) and another in the Balkans, where it may have distinguished itself and garnered the honour Augusta (‘Augustus’ Own’). Veterans settled in the renewed Colonia Iulia Augusta Felix Berytus (Beirut) in Phoenicia (CIL III, 14165–6, which calls it Gallica), and were visited by M. Agrippa in 15 BCE (Strabo, Geog. 16.2.19). From Moesia, Legio VIII was picked to take part in the Marcomannic Campaign of 6 CE under Tiberius, which was aborted, and was redirected to Illyricum to support the effort to quell the Great Illyrian Revolt (Dio 55.32.3–4n, cf. 55.29.3n, 55.30.3–4n). After 9 CE, the troops were stationed near Poetovio (Ptuj) in the new province of Pannonia. Thereafter, veterans settled in Emona and Scarbantia (Sopron; Pliny, Nat. Hist. 3.146).

VIIII Hispana or Hispaniensis. Legio VIIII was one of the oldest legions of Augustus’ army, reconstituted by him from the old legion of Iulius Caesar. It is recorded as serving with Caesar in the Gallic War (58–50 BCE), during which it played an active role (Caes., Bell. Gall. 2.23, 7.47, 8.8). It also fought for him in the war against Pompeius Magnus, fighting at the battles of Ilerda (summer 49 BCE), Dyrrhachium (early 48 BCE) and Pharsalus (9 August 48 BCE). Veterans settling in Italy were recalled to join in Iulius Caesar’s African War (46 BCE), taking part at the Battle of Thapsus (Caes. Bell. Afr. 81) before retiring the following year to Picenum and Histria. Men of Legio VIIII fought under the command of his legal heir in the war against Sex. Pompeius, for which it may have been called Triumphalis (Dessau 2240), and then transferred to Illyricum, where distinguished service may have won it the battle honour Macedonica (Dessau 928). It fought in the Actian War (31 BCE) and then relocated to Hispania Tarraconensis to take part in the War of the Cantabri and Astures (29–19 BCE), during which it likely won its distinctive agnomen Hispana (or Hispaniensis). At the end of the conflict, it may have been drawn down and accompanied M. Agrippa to Gallia Belgica. It may have been part of the force invading Germania under Nero Claudius Drusus in the German War (12–9 BCE) before being re-assigned to Illyricum (CIL 5, 911 from Aquileia; cf. Dio 55.29.1n, 55.32.3n) or Sirmium on the Danube. From 9 through to 14 CE, the legion was in Pannonia in the city of Siscia (Sisak).

X (Fretensis). Needing to bolster his army to wage war against Sex. Pompieus, the heir of Iulius Caesar founded Legio X in 41 or 40 BCE. Theodor Mommsen proposed that the legion won its honorary title Fretensis (‘ironclad’) for guarding the Strait of Misenum and taking part in Mylae and Naulochus (both 36 BCE) under M. Agrippa. It was on the winning side at Actium (31 BCE). Some veterans of Legio X settled in Colonia Veneria (Cremona), while others went to Brixia (Brescia; Dessau 2241, which calls it Veneria), Capua and Colonia Augusta Aroe Patrensis (Patras). The legion was moved about to several different theatres of operation, including Cyrrhus – where it guarded the route from the Euphrates River to Alexandria near Issus, perhaps being present in Armenia when the Parthians handed over the aquilae lost at Carrhae in 53 BCE to Tiberius in 20 BCE – and Macedonia, where an inscription commemorates a bridge constructed by Legio X Fretensis under ‘Pro Praetore Legatus’ L. Tarius Rufus in c. 17 BCE (AE 1936, 18 (Amphipolis) = EJ 268 from Strymon Valley; Dio 54.20.3n). The legion may possibly have been one of the three involved in quelling rebellions of the Jewish messianic claimants Iudas, Simon and Athronges under the provincial legate P. Quinctilius Varus (Joseph., Ant. Iud. 17.10.9) in 4 BCE, thereafter remaining at Jerusalem (Joseph., Ant. Iud. 17.11.1), though the earliest reference to it being in Syria is 17 CE (Tacitus, Ann. 2.57.2), well after Augustus’ principate. Some veterans settled in the colonia of Ptolemais (Acre).

X Gemina. Legio X was one of the oldest legions in Augustus’ army. It served with Iulius Caesar in the Gallic War (58–50 BCE), during which it played an active role, and he regarded it as his favourite legion (e.g. Caes., Bell. Gall. 1.40–42, 2.23, 2.25–26, 7.47, 7.51; Plut. Caes. 19.4–5). It also fought for him in the war against triumvir Pompeius Magnus, fighting at the battles of Ilerda (summer 49 BCE), Dyrrhachium (early 48 BCE) and Pharsalus (9 August 48 BCE). Veterans settling in Italy were recalled to join in Iulius Caesar’s African War, fighting at Thapsus (46 BCE; Caes. Bell. Afr. 81) and Munda (17 March 45 BCE; Caes., Bell. Hisp. 30, 31) before retiring the following year to Narbo Martius (Narbonne), which was renamed Colonia Iulia Paterna Decumanorum (‘the ancestral Julian colonia of the Tenth’) in their honour. In the civil war following the assassination of Iulius Caesar, triumvir M. Aemilius Lepidus reconstituted the unit as Legio X Equistris in 44/43 BCE; it was transferred to M. Antonius and fought at Philippi (October 42 BCE). Antonius took the legion on his unsuccessful campaign to Armenia (36–34 BCE). He then fielded it at Actium (31 BCE), where it surrendered to the victor, but despite settling its veterans at Colonia Augusta Aroe Patrensis (Patras), the serving men mutinied and Caesar’s heir stripped it of its agnomen. Other troops from disbanded units were assigned to the legion and it gained the name Gemina (‘twin’). It was sent to Petavonium (Rosinos de Vidriales) in Hispania Tarraconnensis to take part in the Cantabrian and Asturian War (29–19 BCE), and its presence in the region is attested by inscriptions (e.g. Dessau 2256, 2644). It remained there for the duration of Augustus’ principate. However, for insubordination – specifically ‘demanding their discharge in insolent fashion’ – Augustus ‘disbanded the entire Legio X in disgrace without the rewards which would have been due for faithful service’ (Suet., Div. Aug. 24), though when is not disclosed; and other units, also not disclosed, were similarly punished. Veterans were settled at coloniae Augusta Emerita (Mérida; Dio 53.26.1), Caesaraugusta (Zaragoza) and Corduba (Cordoba), as attested by coins (e.g. RPC 1.16 and 1.325; EJ 342, 343; ILS 2707; cf. Dio 53.26.1).

XI Actiaca (later Claudia). Iulius Caesar founded Legio XI in 58 BCE in readiness for his Gallic War (58–50 BCE), in which it played an active role (Caes., Bell. Gall. 2.23, 8.6, 8.8, 8.24). In January 49 BCE, the legion crossed the Rubicon River with its commander and was billetted in Apulia. It saw action at Dyrrhachium (48 BCE), Pharsalus (9 August 48 BCE) and Munda (17 March 45 BCE), after which it was disbanded and veterans settled at Bovianum (Boiano). Caesar’s heir resurrected the unit and it fought at Philippi (October 42 BCE), and it was in action quelling a rebellion at Perusia (Perugia) that year (CIL XI, 6721, 25–27). It may have taken part in the war against Sex. Pompeius (37–36 BCE) in Sicily. It fought on the winning side at Actium (31 BCE), gaining the legion the agnomen Actiaca (Dessau 2243, 2336) as well as some of its troops – like M. Billiacus, whose tombstone was found at Vicenza (ILS 2243 = EJ 254). While it was stationed at Poetovio (Ptuj), on the eve of the Great Illyrian Revolt (6–9 CE) it arrived to assist Tiberius with legiones IIII Scythica and VIII Augusta under the command of A. Caecina Severus (Dio 55.32.3–4n; cf. 55.29.3n, 55.30.3–4n). After the war, it remained in the region in the new province of Dalmatia, based at the winter camp at Burnum (Kistanje), which it shared with Legio VII. Detachments likely operated across the province, such as at its capital Salonae (Split) and at Gardun, and engaged in road construction. For a discussion of the title Actiaca, see Keppie (1971).

XII Fulminata. Iulius Caesar founded Legio XII (Dessau 2242, CIL XI, 6721, 20–30) in 58 BCE in readiness for his Gallic War (58–50 BCE), in which it took an active part (e.g. Caes., Bell. Gall. 2.23, 2.25, 3.1, 7.62, 8.24; Plut., Caes. 20.7). It was one of the legions which crossed the Rubicon River with its commander in January 49 BCE (Caes., Bell. Civ. 1.15) and fought in the Civil War (e.g. Scaeva, the legion’s eighth-ranking centurio, was rewarded for gallantry with promotion to primus pilus, as cited in Caes, Bell. Civ. 3.53.5) and at Pharsalus (9 August 48 BCE). It was disbanded and its veterans granted land in Parma (45 BCE). Following the assassination of Iulius Caesar, triumvir M. Aemilius Lepidus reconstituted the unit in 44/43 BCE, and gave it to M. Antonius. It may have fought with Antonius against Caesar’s heir at Mutina (Modena) in 42 BCE. It may have been at Philippi (October 42 BCE) and is known from inscriptions on sling bullets (glandes) to have been at Perusia (Perugia). It relocated to Syria and took part in Antonius’ failed Parthian War (39–36 BCE), and, remaining loyal to him (coin Dessau 2241, 1), later fought on his side at Actium (31 BCE). Together with Legio X Gemina, many veterans were settled by Agrippa at Colonia Augusta Aroe Patrensis (Patras, CIL III, 7261 and X, 7371, which uses the agnomen Fulminata) in 16–14 BCE, and Venusia (Venosa, CIL IX, 435). The active men of XII Fulminata were deployed to occupy Aegyptus – probably based at Babylon (Cairo) – perhaps moving to Africa as late as 6 CE, but returned to Syria (CIL III, 6097). In 20 BCE, the legion may have accompanied Augustus and Tiberius to Armenia. In the year Herodes died (4 BCE), under the provincial legate P. Quinctilius Varus, the legion was likely involved in quelling rebellions of the Jewish messianic claimants Iudas, Simon and Athronges. How and where it earned its agnomen – fulminata means ‘lightning strike’ – is unknown. In 14 CE, it was quartered in Syria at Melitene (Malatya) or Raphanaea (Rafniye).

XIII Gemina. Legio XIII was established in 57 BCE by Iulius Caesar from men in Gallia Cisalpina, and saw action (Caes. Bell. Gall. 2.2, 5.53, 6.1, 7.51, 8.2, 8.11, 8.54) during the Gallic War (58–50 BCE). It crossed the Rubicon River with its commander in January 49 BCE (Caes., Bell. Civ. 1.7, 1.12) and was stationed at Apulia while events unfolded. It saw action at Dyrrhachium (48 BCE) and Pharsalus (9 August 48 BCE), after which it was disbanded (autumn 48 BCE). Veterans settling in Italy were recalled to join in Iulius Caesar’s African War (46 BCE) and probably fought with him at Munda (17 March 45 BCE). The legion was then disbanded and its veterans found homes at Hispellum (Spello). Caesar’s heir resurrected the unit to take part in the war against Sex. Pompeius (37–36 BCE) in Sicily (App. BC 5.87). After Actium (31 BCE), it was supplemented with troops from other disbanded legions – on account of which it was called Gemina (‘twin’) – and sent to Illyricum or Gallia Transpadana. Based in Iulia Aemona (Ljubljana), it went on to play an active role in the Alpine War (15 BCE) under the command of Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus. Graffiti on a pottery sherd and a helmet indicate that the legion – or detachments of it – were stationed in Batavodurum (Nijmegen) as part of the invasion force for the German War (12–9 BCE) under the same commander. It was a member of Tiberius’ army group in the Marcomannic Campaign of 6 CE, but when the Great Illyrian Revolt erupted it was dispatched to assist in the effort to quell the insurgency (Dio 55.29.1n, 55.32.3n; Dessau 2638 from Aquileia). After the military disaster at Teutoburg (9 CE), it stayed briefly at Augusta Vindelicorum (Augsburg) in Raetia before relocating to the military district of Germania Superior and sharing the winter camp of Mogontiacum (Mainz) with Legio XIV Gemina, under Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore C. Silius (Tac. Ann. 1.31); it stayed there for the remainder of Augustus’ principate. Veterans settled in Hispellum (Spello; CIL XI, 1933) and at Uthina in Africa (Dessau 6784).

XIV Gemina. Legio XIV was established in 57 BCE by Iulius Caesar from men in Gallia Cisalpina (Caes. Bell. Gall. 2.2, 6.1, 8.4) during the Gallic War (58–50 BCE). It fought for him in the war against Pompeius Magnus, fighting at the battles of Ilerda (summer 49 BCE), Dyrrhachium (early 48 BCE) and very likely at Pharsalus (9 August 48 BCE). Veterans settling in Italy were recalled to join in Iulius Caesar’s African War (46 BCE) before it was disbanded. After 41 BCE, Caesar’s heir resurrected the unit and it took part in the war against Sex. Pompeius (37–36 BCE) in Sicily. After Actium (31 BCE), its veterans were settled in Ateste (Este). The legion was supplemented with troops from other disbanded legions – on account of which it was called Gemina (‘twin’) – and sent to Illyricum, and possibly Gallia Transpadana or Aquitania. It was picked to participate in the Marcomannic Campaign of 6 CE, but when the Great Illyrian Revolt erupted that year it was dispatched to assist in the effort to quell the insurgency (Dio 55.29.1n, 55.32.3n; cf. ILS 2649, CIL 5.8272 from Aquileia). After the Varian Disaster (9 CE), it likely relocated to Vetera (Xanten), under the command of L. Asprenas (Vell. Pat. 2.120.1). It later moved to the military district of Germania Superior (Tac. Ann. 1.37.3), sharing the winter camp of Mogontiacum (Mainz) with Legio XIII Gemina in the military district of Germania Superior under Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore C. Silius (Tac. Ann. 1.31), where it stayed for the remainder of Augustus’ principate.

XV Apollinaris. Faced with the challenge of bolstering his army to wage war against Sex. Pompieus, the heir of Iulius Caesar founded Legio XV in 41 or 40 BCE. After seeing action in Sicily, it likely transferred to campaign in Illyricum (36–35 BCE). It was on the winning side at Actium (31 BCE); perhaps for valour during the battle it earned the honorary title which signifies a sacred association with Augustus’ favourite god, Apollo (Suet., Div. Aug. 18.2). Thereafter, its veterans were settled in Ateste (Este; CIL V, 2516). It was picked to participate in the Marcomannic Campaign of 6 CE, but when the Great Illyrian Revolt erupted that year it was dispatched to assist in the effort to quell the insurgency (Dio 55.29.1n, 55.32.3n; CIL V, 891, 917, 928 from Aquileia), perhaps stationed at Siscia (Sisak). Following the Varian Disaster (9 CE), Legio XV may have relocated temporarily to Iulia Aemona/Emona (Ljubljana; CIL III, 10769; Dessau 2264) or Vindobona (Vienna) in Pannonia. By the time of Augustus’ death in 14 CE, it was probably already installed at Carnuntum (located east of Vienna) on the Danube River. After the mutiny of 14 CE, veterani settled in Emona (CIL III, 3845 = ILS 2264) and Scarbantia (modern Sopron; CIL III, 4229, 4235, 4247, 14355/14; Pliny, Nat. Hist. 3.146). For a detailed discussion, see Šašel Kos (1995).

XVI Gallica. Needing to bolster his army to wage war against Sex. Pompeius, the heir of Iulius Caesar founded Legio XVI in 41 or 40 BCE, giving it the honorary title which signifies Apollo. After seeing action in Sicily, it transferred to Africa. After Actium (31 BCE), it saw service in Raetia under Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus. It is called Gallica on a few inscriptions (e.g. Dessau 2034). From its base at Mogontiacum (Mainz), it took part in the German War (12–9 BCE). It was one of the units chosen to participate in the Marcomannic Campaign of 6 CE, but when the Great Illyrian Revolt broke out that year it was dispatched to assist in the effort to quell the insurgency. Following the Varian Disaster (9 CE), Legio XVI relocated to Germania (Dessau 2265, 2266), temporarily to Ara Ubiorum (Cologne). It returned to Mogontiacum (Tac. Ann. 1.37.3), the winter camp it shared with Legio XIV in the new military district of Germania Superior under Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore C. Silius (Tac. Ann. 1.31), where it remained well after Augustus’ death in 14 CE.

XVII. Absent of proof, its existence is inferred because there was a Legio XIIX and a XIX. Nothing is known about the origins of Legio XVII. It may have been founded by Iulius Caesar’s heir in 41 or 40 BCE for the war against Sex. Pompeius. After Actium (31 BCE), it may have seen service in Gallia Aquitania under command of M. Agrippa, sent there to put down a rebellion in 39 BCE. It may have taken part in the Alpine War (15 BCE) under Tiberius, before relocating to the Rhine. During the preparations for the German War (12–9 BCE) under Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, it may have been quartered at Vetera (Xanten), meaning ‘The Old One’ – before moving to Oberaden, Holsterhausen or Haltern as the army group advanced into Germania along the Lippe River and began the work of pacification under Tiberius (8 BCE and 4–5 CE). Under Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore P. Quinctilius Varus, it was annihilated in 9 CE and never reconstituted.

XIIX. Nothing is known about the origins of Legio XIIX (not ‘XVIII’). It may have been founded by Iulius Caesar’s heir in 41 or 40 BCE for the war against Sex. Pompeius. After Actium (31 BCE), it may have seen service in Gallia Aquitania under command of M. Agrippa, sent there to put down a local rebellion in 39 BCE. It may have taken part in the Alpine War (15 BCE) under Tiberius, before relocating to the Rhine. During the preparations for the German War (12–9 BCE) under Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, it may have been quartered at Ara Ubiorum (Cologne) or Novaesium (Neuss), before moving to Oberaden, Holsterhausen or Haltern as the army group advanced into Germania along the Lippe River and began pacification operations under Tiberius (8–7 BCE and 4–5 CE). Under Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore P. Quinctilius Varus, it was annihilated in 9 CE. It was never reconstituted. A monument was erected to centurion M. Caelius, who fell ‘in the Varian War’, by his son and brother (CIL XIII, 8648 = AE 1952).

XIX. Nothing is known about the origins of Legio XIX. It may have been founded by Iulius Caesar’s heir in 41 or 40 BCE for the war against Sex. Pompeius. After Actium (31 BCE), it may have seen service in Gallia Aquitania under command of M. Agrippa, sent there to put down a rebellion in 39 BCE. It likely took part in the Alpine War (15 BCE) under Tiberius – attested by the find of an iron catapult bolt (fig. 6) embossed with the signature ‘LEG XIX’ found at Döttenbichl (near Oberammergau in Bavaria). During the preparations for the German War (12–9 BCE) under Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, it may have been stationed at Vetera (Xanten) – meaning ‘The Old One’ – before moving to Oberaden, Holsterhausen or Haltern as the army group advanced into Germania along the Lippe River and began pacification operations under Tiberius (8 BCE and 4–5 CE). Under Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore P. Quinctilius Varus, it was annihilated in 9 CE and its aquila was taken as a trophy by the rebels. Although the legion’s eagle standard was recovered from the Bructeri in 15 CE by L. Stertinius for Germanicus Caesar (Tac., Ann. 1.60.4), it was never reconstituted.

XX Valeria Victrix. Legio XX may have been founded after Actium (31 BCE), when units from opposing sides were combined. It went to Hispania Taraconnesis as part of the grand army in the Cantabrian and Asturian War (29–19 BCE), after which veterans were settled at coloniae Augusta Emerita (Mérida; Dio 53.26.1; CIL II, 32 of miles C. Axonius), founded in 25 BCE. Detachments appear to have gone to the Balkans in 20 BCE (Dessau 2651) or northern Italy (CIL V, 939, 948). It received its signa from Tiberius (Tac. Ann. 1.42), perhaps on the occasion of the Alpine War (15 BCE). Stationed at Burnum (Kistanje; Dessau 2651), it was to participate in the Marcomannic Campaign of 6 CE (Dessau 2270), but when the Great Illyrian Revolt (6–9 CE) erupted that year, it was dispatched to assist in the effort to quell the insurgency. Under Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore of Illyricum M. Valerius Messalla Messallinus, it found itself surrounded by the Pannonii and had to cut its way through (Vell. Pat. 2.112.2, cf. Dio 55.30.1n). The honorific title Valeria Victrix was likely awarded during Augustus’ principate (Dio 55.23.6) and may indicate its close connection with the Legatus Augusti. After the Varian Disaster (9 CE), it was based at a winter camp shared with Legio I located in the vicinity of Ara Ubiorum (Cologne); in 14 CE, it reported to Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore A. Caecina Severus of the new military district of Germania Inferior (Tac. Ann. 1.37, 1.44).

XXI Rapax. The origins of the legion are obscure. Legio XXI may have been founded by Iulius Caesar’s heir in 41 or 40 BCE to bolster his forces for the war against Sex. Pompeius. It may, however, have been established to take part in the Alpine War (15 BCE) by Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus, as inscriptions of soldiers (CIL V, 4858, 5033) show their places of birth to have been in the foothills of the Alps, e.g. Brixia (Brescia) and Tridentum (Trento). It was stationed in Vindelicia down to 6 CE (Dessau 847), but when the Great Illyrian Revolt erupted it assisted in the effort to quell the insurgency (Dio 55.29.1n, 55.32.3n). After the Varian Disaster of 9 CE, the legion was quartered at Vetera (Xanten), which it shared with Legio V (Tac. Ann. 1.31, 1.45). In 14 CE, its legate reported to the Legatus Augusti Pro Praetore of the military district of Germania Inferior, A. Caecina Severus. The circumstances leading to its agnomen Rapax – meaning ‘grasping’ or ‘rapacious’ – are not recorded.

XXII Deiotariana. When the client kingdom of Galatia was bequeathed by Amyntas to Augustus in 25 BCE (Dio 55.26.3), its army was absorbed as a iusta legio into the Romans’ as Legio XXII (Dessau 2274). Its agnomen paid homage to Deiotarus (c. 105–40 BCE), leader of the Tolistobogii, who had been loyal to Rome during the Mithradatic Wars (89–63 BCE) and stood with Iulius Caesar against Pharnakes (Pharnaces) II, king of Pontus. Relocated to Aegyptus, from 35 BCE it shared a winter camp at Alexandria with Legio III Cyrenaica. It may have been active in the attack on Arabia Felix (Yemen) under equestrian Praefectus Aegypti Aelius Gallus (26–25 BCE); and against Nubia under C. Petronius (24 BCE), culminating in the sacking of its capital city, Napata (22 BCE).

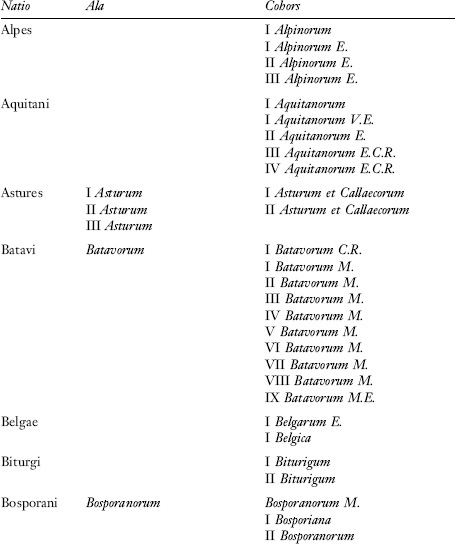

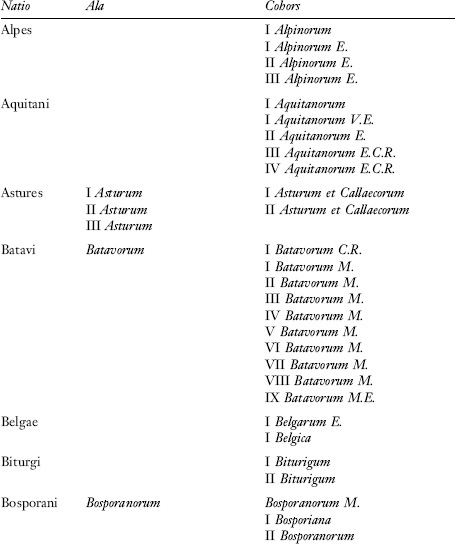

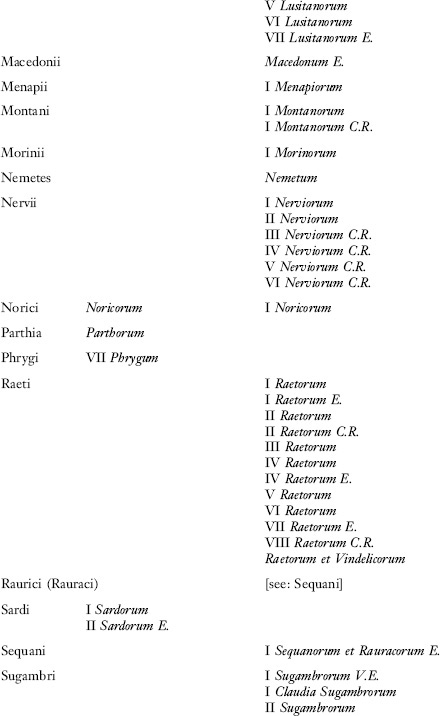

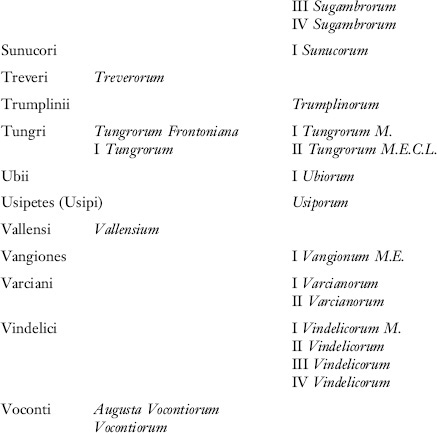

4. Non-citizen Army (Auxilia)

The many long-serving, professional auxiliary units in Augustus’ army comprised of alae of cavalry and cohortes of infantry from ad hoc drafts of subject peoples and treaty allies (socii, foederati). In total, these units likely matched the legions for headcount (Tac., Ann. 4.5) – but Tacitus remarked that ‘any detailed account of them would be misleading, since they moved from place to place as circumstances required, and had their numbers increased and sometimes diminished’ (Tac., Ann. 4.5); and Cassius Dio did not know how many there were either (Dio 55.24.5 and 55.24.8).

Their precise organization is not entirely clear. From the treatise De Munitionibus Castrorum, written by an unknown author commonly referred to as ‘Pseudo-Hyginus’ who lived well after Augustus’ time, there appear to have been:

• Ala quingenaria: ‘Wing of 500’, a cavalry unit comprising sixteen turmae of thirty to thirty-two men, each commanded by a decurio, for a total of 512.

• Ala milliaria: ‘Wing of 1,000’, a cavalry unit comprising twenty-four turmae of thirty to thirty-two, each commanded by a decurio, for a total of 768; or by other reckoning twenty-four turmae of forty men, for a total of 960, plus officers.

• Cohors peditata quingenaria: ‘Cohort of 500 Foot’, a combat unit of six centuriae of eighty infantrymen, each commanded by a centurio, for a total of 480 plus officers.

• Cohors peditata milliaria: ‘Cohort of 1,000 Foot’, a combat unit of ten centuriae of eighty infantrymen, each commanded by a centurio, for a total of 800 plus officers.

• Cohors quingenaria equitata: ‘Cohort of 500 Horse’, a part-mounted mixed unit of eight or ten turmae of thirty-two cavalrymen each plus six centuriae of sixtyfour or eighty infantrymen for a total of 512–608 plus officers.

• Cohors milliaria equitata: ‘Cohort of 1,000 Horse’, a part-mounted mixed unit of eight or ten turmae of thirty-two cavalrymen each plus ten centuriae of sixtyfour or eighty infantrymen for a total of 1,040 plus officers.

Examples include the Cohors I Batavorum C.R. a milliaria equitata, formed of Batavi cavalry and infantry from the Netherlands; Cohors I Ubiorum peditum et equitum, a unit of Germanic infantry and cavalry from the Rhineland (CIL X, 4862 = ILS 2690); Cohors II Ituraerorum (ILS 8899), a mounted unit of Syrian-Arabic people living in the region of modern Lebanon (sagitarii Ituraei were part of Iulius Caesar’s army in 46 BCE (Caes., Bell. Afr. 20.1); and Cohors Trumplinorum (CIL V, 4910 Raetia; ILS 847), an infantry unit comprised of Trumplini recruited from around Brixia (Brescia) in the foothills of the Italian Alps. They fought with their own weapons, using their preferred fighting techniques that made them distinct.

A cohors was usually commanded by praefectus (e.g. Ti. Flavius Miccalus: Istanbul, Arkeoloji Müzesi Inv. 73.7 T) recruited from the Ordo Equester. Augustus also experimented by permitting the sons of senators ‘the command [as praefecti] of an ala of cavalry as well and, to afford all of them the opportunity to experience life in camp (expers castrorum), he usually appointed two senators’ sons to command each ala’ (Suet., Div. Aug. 38.2; CIL XIV, 2105).

In addition, there were units under the command of local leaders (duces), such as the Ala Atectorigiana, presumably led by a Gallic dux named Atectorix (CIL XIII, 1041 = ILS 2531). Avectius and Chumstinctus came from the Belgic nation of the Nervii (Livy, Peri. 141), and as tribuni were presumably in command of units of their countrymen, fighting on the side of Nero Claudius Drusus in Germania in 10 BCE. Romans could be involved in training the troops of these allies, as in the case of the cavalry and infantry of Thracian king Roimetalkes (Florus 2.27). They too fought with their own weapons, using their preferred fighting techniques. Their local knowledge could be useful when trekking through unfamiliar territory. The Frisii were able to assist Nero Drusus on his expedition to and from Germania in 12 BCE (Dio 54.32.2–3; Tac., Ann. 4.72). Tiberius picked Namantabagius, ‘a conquered barbarian’ (a man from Germania, Raetia or Noricum) to accompany him on the journey to meet his dying brother (Val. Max. 5.3.3). Iulius Caesar used trusted Romanised Gallic nobles as interpreters (Caes., Bell. Gall. 1.47 and 1.53).

The regular men of a cohors were recruited from non-Romans of the same nationality. It is not clear if their service at this period was stipulated at sixteen or twenty years, or if it ceased when the leader died, after which they may have continued to serve under another commander, or if disbanded, perhaps they transferred to a different active contingent.

For detailed discussions of the evidence for auxilia, see Cheesman (1914), Haynes (2013), Holder (1980), Kennedy (1983), Keppie (1996), Knight (1991), Matei-Popescu (2013), Meyer (2013), Roxan (1973), Saddington (1985) and Spaul (2000). This list of auxiliary units is not exhaustive, but is indicative of the variety of national alae and cohortes likely in the service of Augustus.

Abbreviations used: E. = equitata; C.R. = civium Romanorum; M. = milliaria; S. = sagittariorum; V. = veteranorum.

5. Navy (Classes)

Augustus had some 900 warships (naves longas), 300 of which had been captured from Sex. Pompeius in 36 BCE (App., Bell. Civ. 5.108, 5.118) and 300 from M Antonius at Actium in 31 BCE (RG 3.4, Plut. Ant. 68). Navies were distributed around the Roman Empire – attached to provincial commands, or flotillas of vessels belonging to particular legions located on rivers. Each was commanded by an equestrian rank praefectus classis reporting directly to Augustus (cf. Caes., Bell. Civ. 1.36). After Actium, ships were generally either triremes (three banks of oars) or biremes (two banks), with a large single mainsail, steered by two large oars mounted at the stern. The crew of each ship was commanded by a centurion as captain (navarchus), with his optio, standard bearers and trumpeters, a helmsman (gubernator), marines (milites classiarii), armed sailors (nautae) and oarsmen (remigae) supplemented by an artillery crew (balistarii) and archers (sagittarii). The shipyards contained the workshops of the carpenters (fabri navales), specialist workmen (artifices), sail and rigging makers (velarii) and offices of the administrative staff.

For detailed discussions of marines, their organization and types of warships, see D’Amato (2009); Keppie (1996); Kienast (1966); Pitassi (2011); Saddington (1990); and Starr (1941).

The fleets known to have been in operation under Augustus were:

Alexandrina. Founded by Imp. Caesar around 30 BC, the Classis Alexandrina likely initially comprised of ships that fought at the Battle of Actium. Its vessels patrolled the eastern Mediterranean, Nile River and Red Sea. For his campaign in Arabia Felix Aelius Gallus commissioned eighty new vessels (biremes, triremes and galleys) from the shipyard at Kleopatris (Strabo, Geog. 16.4.23).

Foroiuliense. Ships captured at the Battle of Actium (31 BCE) were sent by Augustus to Forum Iulii (Fréjus), where they patrolled the contiguous coastline of Gallia Narbonnensis for the remainder of his principate (Tac., Ann. 4.5).

Germanica. Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus constructed a fleet of ships to transport his army via a specially constructed canal (fossa Drusiana or fossae Drusinae) deep into Germania during the war (12–9 BCE). It may have been based at Bonna (Bonn) or distributed among the winter camps along the lower Rhine River (Florus, 2.30.26). It was the first Roman fleet to reach Jutland (Augustus, RG 26.4; Pliny the Elder, Nat. Hist. 2.67. 167; Suet., Claud. 2.1.), but was shipwrecked on the Frisian coast when returning to the Rhine from the Ems (12 BCE). Tiberius may have used many of the same vessels during his punitive expedition of Germania, which reached the Elbe River in 5 CE (Vell. Pat., 2.106, 2f.; cf. 2.121.1).

Misenensis. When ships carrying grain and oil sailing from North Africa and Sicily to Rome were attacked by Sex. Pompeius, M. Agrippa was commissioned in 37 BCE to build a fleet of ships to wage war against him. The hulls of the triremes and quinqueremes [three banks of oars] were provided by the coastal cities of Italy and brought to a harbour – the Portus Iulius, which he specially constructed at great speed at Cumae on the Bay of Naples – to be outfitted and receive their crews (Dio, 48.49.4–50.1–3; App., Bell. Civ. 5.11; Pliny the Elder, Nat. Hist. 36.125; Suet., Div. Aug. 16.1; Vell. Pat., 2.79.1–2; Vergil, Georg. 2.161–64). After the war, the fleet was moved to Misenum, from which it continued to patrol the shipping lanes between Africa and Rome.

Ravennas. The fleet at Ravenna was constructed to guard the Adriatic coast of Italy from raids by forces of Sex. Pompeius in Illyricum (App. BC 5.80). After the war, it continued to patrol the region for the remainder of his principate (Tac., Ann. 4.5). The port was connected to the southern branch of the Po River by a canal (Fossa Augusta).

Sociae Triremes. An unknown number of other fleets or flotillas were stationed with the legions or auxilia (Tac., Ann. 1.11), and also operated by client kings around the empire (e.g. Herodes, whose Royal Harbour at Caesarea Martimae – possibly equipped with ship sheds – was begun around 20 BCE (Joseph., Ant. Iud. 16.21).

6. Conscript and Volunteer Corps (Cohortes Ingenuorum and Cohortes Voluntariorum)

Under Augustus, there were up to forty-six units of conscripts and volunteers representing some 23,000 men (equivalent to four legions).

Some cohorts were comprised of centuries of non-volunteer citizens, which may have been created for special duties or missions (e.g. Cohors Augusta I (CIL X, 4862), Cohors II Classica (CIL III, 6687)). The praefectus C. Fabricius Tuscus commanded one such unit known as Cohors Apulae Civium Romanorum (AE 1973, 501), recruited from the men of Apulia before 6 CE, which was at some point transferred to province Asia with its garrison in or near Alexandria Troas. Cohors I Aquitanorum Veterana (CIL XIII, 7399a) was formed from the men of the fleet at Forum Iulii for service in Aquitania to support the Bellum Cantabricum in 26 BCE.

In times of emergency, a levy of freeborn citizens (dilectus ingenuorum) could raise men for new units to serve in the nation’s defence. By an ancient law, men from 17 to 46 were eligible for the draft (Polybius 6.19.2; Aulus Gellius 10.28.1), though men under 35 were most sought-after (cf. Livy, AUC 22.11.9; Veg. 1.4). Men were selected by lot and the chosen ones took the military oath (Dio 38.35.4). They were commanded by tribunes (e.g. CIL III, 14216, 8 Dolbreta). Two or six units were created from enforced levies held during the Great Illyrian Revolt (a.k.a. The Batonian War) of 6–9 CE, which also included freedmen (liberti), both under the command of Germanicus Caesar (Dio 55.31.1, Suet., Div. Aug. 25.2); but in the aftermath of the Varian Disaster of 9 CE, Roman citizens (many from among the city’s disgruntled poor), freedman and slaves – quickly manumitted and made freedmen to make up the numbers – were recruited (e.g. Dio 56.23.3; Vell. Pat. 2.111.1; Tac. Ann. 1.31; Macrobius, Sat. 1.11.32) and accompanied Tiberius back to Germania (Dio 56.23.3). Freed slaves serving with levied cohorts were among those encouraging the legionaries at Ara Ubiorum in Germania Inferior to mutiny in 14 CE (Tac., Ann. 1.31).

Units of the free born – Cohortes Voluntariorum – were kept separate from those of the freedmen and they were issued different arms and equipment (Suet., Div. Aug. 25.2). One such was Cohors I Campana, recruited from men of Campania (CIL III, 8438 Narona/Dalmatia = ILS 2597). An inscription from Illyricum (CIL III, 10854 Siscia) records a Cohors XXXII Voluntariorum Civium Romanorum, suggesting there were up to thirty-two of these in active service under Augustus.

For a detailed discussion, see Brunt (1974); Orth (1978); Speidel (1976); and Spaul (2000).

7. Paramilitary Urban or City Police (Cohortes Urbanae)

The Cohortes Urbanae were instituted by Augustus to maintain peace and order in the City of Rome (Dio 52.21.1–2; Suet., Div. Aug. 37), perhaps as early as 27 BCE. Commanded by the Praefectus Urbi (a former consul, whose jurisdiction covered the city and up to 100 miles around (Dio 52.33.1) – most famously L. Calpurnius Piso Caesonius (Tac., Ann. 6.10)), the corps complemented the Cohortes Praetoriae and comprised three cohorts, numbered X through to XII, to continue the sequence – and each comprised six centuries. As paramilitary police, the urbaniciani were employed to enforce public order and deal with riots. During the months following the Clades Variana of 9 CE, they maintained patrols (excubiae) throughout the city during the night time (Suet., Div. Aug. 23.1). A fourth unit of the Cohortes Urbanae was also stationed in Colonia Copia Felix Munatia (Lugdunum, Lyon) to guard the mint, which produced silver and coins from 15 BCE onwards. An optio carceris, a deputy to a centurion in charge of a prison, is recorded both in Rome and Lugdunum (CIL IX, 1617 = ILS 2117; CIL XIII, 1833 = ILS 2116; and CIL VI, 531 = ILS 3729 (238–244)). The men of the Urban Cohorts each received 500 sestertii from the estate of the deceased princeps, HS200 more than the regular legionaries (Suet., Div. Aug. 101.2).

For a detailed discussion, see Echols (1958); Freis (1967); and Nippel (1995).

8. Firefighters (Vigiles Urbani, Cohortes Vigilum)

During the Late Republic, powerful Roman families owned troops of slaves to guard their properties and fight the fires which frequently broke out and devastated regions of the city. The most notorious of them belonged to M. Licinius Crassus: if fire threatened a building, his men would arrive, demand payment from the owner to extinguish the fire or else watch the property go up in flames (Plut. Crass. 2). C. Cilnius Maecenas urged Augustus to establish a corps under an equestrian praefectus (Dio 52.24.4). In 26 BCE, Augustus assigned firefighting to the aediles; in 22 BCE, Augustus entrusted the curule aediles with the responsibility for putting out fires in Rome, for which purpose he granted them 600 slaves as assistants (Dio 53.24.6, 54.2.4n, cf. Dig. 1.15.1). In 7 BCE, when the city of Rome was organized into fourteen regions (comprising over 200 vici, or wards), this function was transferred to the colleges of vicomagistri (Dio 55.8.7n).

In 6 CE, a year during which Romans living in the city suffered a wretched combination of severe famine and devastating fires, Augustus founded the Vigiles Urbani, the ‘Urban Watch’ (or Cohortes Vigilum), specifically as a firefighting force (Suet. Div. Aug. 25.2, 30.1; Dio 55.26.1, 4–5; Tac. Ann. 13.27.1). Commanded by an equestrian Praefectus Vigilum appointed by Augustus himself (Dio 52.33.1, 58.9.3; Dig. 1.2.2.33), the 6,000 men were organized into four cohortes (Dio 55.24.6), each of seven centuriae, recruited from among liberti, freedmen (Suet. Div. Aug. 25.2; Dio 55.26.4). Equipped with axes, buckets, rope, chain and cart-mounted water pumps (siphones), they also served as the city’s night watch and assisted the Cohortes Urbanae in enforcing public order, arresting thieves and capturing runaway slaves (cf. Dio 55.26.4 on the praefectus’ duties). Funded by a 2 per cent tax on the sale of slaves (Dio 55.33.4), the Vigiles had barracks located in the city and proved very popular with the public (Dio 55.26.5). An optio carceris in charge of the prison is recorded with the vigiles (CIL VI, 32748; VI, 1057, 2, 10 (205)).

For a detailed discussion, see Daugherty (1992).