How to Get Honest with and about Yourself

Over the years, I’ve mentored hundreds of entrepreneurs to help them build seven-figure companies. It’s one of my favorite types of work, because entrepreneurs have the singular authority to unstick themselves and take action. But that’s the funny part: even though they arrive at my doorstep unconstrained by bureaucracy, they still allow self-limiting beliefs to creep in and put giant roadblocks in their way (as have I, mind you). I can’t tell you how many times a “business issue” turns out to be some sort of cockamamie mental assumption the entrepreneur has made, which may be either partially or entirely untrue. As I’ve learned from their journeys and from my own: eliminate the belief, solve the problem.

CREATING YOUR VALUES HIERARCHY TO GET INTO ALIGNMENT WITH YOUR TRUE SELF

As we saw with many of the organizations in this book, success starts with who. The same rule applies to you, as a leader: when you start with who you are, you gain an operating system that allows you to navigate complex challenges using your honest identity as a compass. When you know who you really are and what you really want, you can begin executing toward your greatest self. Otherwise, you could spend a lifetime failing at something you never even wanted in the first place, which I consider to be one of the saddest afflictions of all.1

To get at your honest self in a more structured way, here’s a framework worth pursuing if you desire to better understand who you are, what you stand for, and what might be living in that blind spot of yours. It’s called a Values Hierarchy, and it takes your personal core values and prioritizes them to illuminate some interesting aspects of your belief system that make you the leader you are. Your values hierarchy can both guide your decision-making and even help explain some of your frustrations, since it should clearly spell out which habits and behaviors matter to you, and which you abhor.

To make your own values hierarchy, brainstorm a list of core values that resonate with you—they could be words like “happy” and “truth,” or “passion” and “speed.” Really, it could be any word that can help another person more deeply understand who you are and what you believe in.

To make your own values hierarchy, brainstorm a list of core values that resonate with you—they could be words like “happy” and “truth,” or “passion” and “speed.” Really, it could be any word that can help another person more deeply understand who you are and what you believe in (I’ve included a list of five hundred core values in the appendix to help you get started). From there, pick six to ten of your top values, and prioritize them in order from most important to least important. Which ones make up your foundation? Which indicate where you’re trying to go, or who your most ideal self might be?

My hierarchy starts with “honesty” and “passion,” includes such personal ideals as “accountability” and “velocity,” and moves upward to my top values of “service” and “enlightenment.” So although I own a foundation of several critical values for which I stand, my ultimate value is helping others achieve greatness, which signifies a more enlightened life. When I encounter someone who frustrates me or doesn’t work well with me, chances are that I can explain the issue as a mismatch in values, which I had never even thought to consider before writing out my own hierarchy. For instance, when I encounter someone who is fundamentally dishonest, or doesn’t value helping others, or doesn’t respect others, or generally makes decisions at a turtle’s pace, I tend to cringe—and my values hierarchy tells me why. When you design your own hierarchy, you’ll see other people and organizations very differently, and more fundamentally. Your values hierarchy will help you explain why certain clients work well with you, and why some never seem to click. It will help you explain why some friends drift away from you over the years, while other, newer friends jibe with you so well, and so quickly.

In fact, your values hierarchy can explain most interpersonal differences you might want to investigate—including family members, friends, significant others, partners, employees, clients, and more. Having a values match is like having a DNA match; it’s both undeniable and deeply rooted in your own inescapable truth. You gain real power when you intimately know who you are, right down to the values that make up your belief system. Because when you properly get honest about who you are, as we’ve seen earlier, you can literally change your world—putting yourself into alignment with your best life.

Your values hierarchy will also tell you why you feel guilt, shame, or elation when you take certain actions or exhibit certain behaviors. For instance, “service” and “accountability” are higher up on my ladder than “honesty” is, which means that when gray areas arise where I’m held accountable to help someone, I might just be willing to lie. Which brings us back to chapter four, where I confessed that I used to roll over like a dog for clients who insisted on building marketing campaigns based on their personal whims instead of on their customers’ feedback. I was faced with a common challenge for entrepreneurs: Take the money and feed my employees’ families? Or forgo the opportunity and risk having to let good people go? Because service and accountability rank higher than honesty on my ladder, I chose to go along with those clients even though the honest thing to do would have been to walk away. Rest assured, honesty won out in the end. My shitty short-term thinking resulted in unhappy clients and unhappy team members, and I had to learn—the hard way, as usual—that if I were truly interested in serving others and being accountable, I had to admit that a business built with mismatched clients didn’t serve anyone responsibly. I learned two important lessons in those years: first, that we can share values and still come into conflict if our values end up in different orders of importance; and second, that knowing my values—and their order—gives me an extraordinary tool to assess my options and choose the right actions for long-term business success and personal fulfillment. Oh, and let’s not forget the third lesson: getting honest about what my values actually mean is really, really important.

Your values hierarchy will also tell you why you feel guilt, shame, or elation when you take certain actions or exhibit certain behaviors.

Today, I think about my values hierarchy in almost every interaction I have. It’s one of those guiding frameworks that, once completed, has accumulated more and more uses throughout my business and personal life. After more than a dozen years of helping companies grow, I can confidently tell you that countless entrepreneurs and Fortune 500 CEOs alike have failed not because of a lack of ability but because their most fundamental assumptions about their personal and organizational identities and beliefs were somehow misaligned with the truth.

UNDERSTAND YOURSELF, OR YOUR BIASES MIGHT EAT YOU ALIVE

If the leaders in this book are correct that long-term organizational performance starts with a leader’s ability to be honest with the self, then exploring your values, beliefs, and biases is a supremely important step toward achieving massive success. One of the most concise summaries of our human biases comes from the aptly named book Predictable Surprises: The Disasters You Should Have Seen Coming, and How to Prevent Them, by Harvard Business School’s Michael D. Watkins and Max H. Bazerman. In it, they lay out a bevy of “psychological vulnerabilities,” or cognitive biases that “can lead us to ignore or underestimate approaching disasters.” Their list of the most common biases includes:

Believing things are better than they really are.

Believing things are better than they really are.

Giving high but unwarranted weight to evidence that supports one’s own beliefs, and discounting evidence that does not support those beliefs.

Giving high but unwarranted weight to evidence that supports one’s own beliefs, and discounting evidence that does not support those beliefs.

Trying to maintain the status quo while downplaying the importance of the future.

Trying to maintain the status quo while downplaying the importance of the future.

Only giving weight to things we have experienced firsthand and not properly prioritizing problems we haven’t personally experienced.

Only giving weight to things we have experienced firsthand and not properly prioritizing problems we haven’t personally experienced.

ACTIONS TO CONSIDER

ACTIONS TO CONSIDER

1.Create your values hierarchy by writing down all the values you think resonate with who you (really) are.

2.Try to determine the top six to ten true core values that are most important to you. You’ll know they’re right when they make you happy to think about and act on, and when it makes you angry to see others violate them.

3.Put your values in order from most to least important to you and post your hierarchy where you can see it as a guide for when situations (or people) become challenging and you’re faced with tough decisions.

Do a Wikipedia search for “list of cognitive biases.” You’ll find plenty that pop out when we least expect them and ruin our opportunities for success. And the pressure to succumb to our biases doesn’t only come from within; external forces, like advertisers and news outlets, constantly fight to exploit our biases. For instance, one of the most powerful psychological persuasion techniques is the art of framing, which means presenting a certain concept in a certain way in order to sway an opinion (like the feed-forward framing technique we learned in the last chapter). The news does this all the time. If you watch two different news outlets, you’ll see it: the same story, with the same facts, presented in two very different ways in order to give the facts a positive or negative inclination. We would all do well to identify the seemingly innocuous phrasing that peppers news stories. For instance, compare the made-up example of a news headline: “America Decides to Withdraw Its Military Presence and Send Brave Americans Home to Their Families” with “America Backs Out of Its Military Commitment by Withdrawing Thousands of Essential Support Personnel.” Same story; two different connotations.

We do this in our personal lives, too, when we tell small children about all the fun benefits of going to the dentist while conveniently leaving out the drilling-into-your-skull part. Alternative facts are a real thing in a world where we get to make choices about which facts to present to others, which means it’s up to us to look skeptically at the information coming at us to ask whether we’re being led astray by those who are exploiting our preconceived notions of what’s true in order to push an agenda. Most importantly, we must be honest with ourselves about how we naturally pursue facts that align with our belief systems instead of properly considering all sides and getting to the objectivity of the matter. We cling to the facts we prefer as a matter of psychological safety, and it’s quite possibly the most dangerous characteristic that a true leader should never possess.

Just between us, I will let you in on a secret about how you can get the best marketing results today (or any manner of business results, for that matter). In fact, I could draw you a tidy little graph to show you what we’ve experienced with our clients. On the x-axis would be the amount of biases that our client has, from many to few, going left to right. On the y-axis would be the results of our marketing campaigns, from poor to great, ascending the y-axis. The graph would look like an exponential, positive-sloping curve rising from the lower left to the upper right. In other words, the more biases our clients have exhibited and imposed on us—personally and organizationally—the lower our performance on their behalf. Those clients with few biases—the ones who have used a Waterfall Culture to hand us a budget, participate open-mindedly, and give only one directive (grow our revenues or get fired)—have done exponentially better.

THE ROOT OF PERSONAL AND BUSINESS GROWTH: GETTING HONEST ABOUT YOUR BULLSHIT

In one coaching call, I was talking to a client about his “sales problem.” He had created a bolt-on monitoring tool that, when installed at water utility companies, instantly saved the utility thousands of dollars each year. But he was stuck, unable to figure out how he could create a juicy, cash-flowing business on inbound requests and referrals alone.

“Why not build a sales program where you create a leads list and start cold-calling?” I asked simply.

“Oh,” he assured me, “I could never do that. I hate sales calls, so I don’t want to be that guy and bother everyone.”

“I see,” I responded. “So what you’re saying is, you’ll only sell to people who call you?”

“Yes, exactly,” he replied, sure that he had gotten through my thick skull.

“OK,” I began, “so what you’re saying is, you’ll only sell to people who are lucky enough to find out about you and then bold enough to call you?”

“Well,” he wavered, “I suppose that’s true . . . and as I said, I don’t want to bother people!”

I pushed him. “So what you’re saying is, water utilities that are lucky enough to find you and bold enough to pursue you are the only water utilities that deserve to save money?”

“W-well . . .” he stuttered.

“And that all other water utilities that aren’t lucky enough to stumble upon you and brave enough to start a conversation with you . . . they don’t deserve to save money?”

The line went dead. Silence . . . until he started laughing. “Well,” he admitted, “I guess you got me there. I just never thought about it that way.”

Brutal truth: leading is about getting the fuck out of your own way and helping those around you get the fuck out of theirs. And that’s how leadership and innovation go hand in hand. Sure, you could create an innovation “division,” where a handful of R&D folks are responsible for creating new products or services. But what about all the brains that come to work and think about your organization every day? They may not share your own self-limiting bullshit . . . and if you give them the ability to voice their ideas, some of that brilliance will push through even the reddest of bureaucratic tape. I always marvel at how others marvel at innovation, like it’s some LSD trip that only a select few Einsteinian business mavens can achieve. But it’s actually quite simple to create a culture of innovation, built on sound leadership principles that help remove roadblocks and get everyone at your organization thinking about how to make meaningful, lasting changes. Honest innovation starts with you, the leader—and I say that without regard for whether you’re in a position of authority or not. Every person—from the entrepreneur and CEO to the doorman at The Ritz-Carlton and the manager of a Domino’s Pizza store—has the power to be a leader, if only they will take on a leader’s responsibility to confront and eliminate harmful biases and blind spots.

Every person—from the entrepreneur and CEO to the doorman at The Ritz-Carlton and the manager of a Domino’s Pizza store—has the power to be a leader, if only they will take on a leader’s responsibility to confront and eliminate harmful biases and blind spots.

Get Honest With Yourself to Eliminate Dangerous Silos

As we’ve discussed, the most heinous act a leader can commit is to brush aside objective information in favor of clinging to subjective insights. Like water to a river valley, information is the flowing force for giving life to an organization. If your information can flow freely around the organization without encountering roadblocks (i.e., you), it will always achieve a higher power than if it is locked down in individual departments. By achieving a higher power, I mean that the information will serve the greatest number of people, so that those people may in turn serve customers in the most impactful, transparent, and authentic ways.

In an age where information is power, consider the amount of information that is withheld interdepartmentally, for political or other reasons, and the impact that positive information could otherwise have. When it comes to silos, make no mistake—the end loser is the customer, and there’s an opportunity cost to your organization. When your people divert time and energy toward managing political silos, they’re not focusing on the customer. When departments sabotage relationships inside or outside the organization, they not only divert time and energy away from customers but they also lose the opportunity cost of what the department could have achieved if it hadn’t been engaged in such ridiculous folly. Customers—and your bottom line—lose on both ends: what is and what could have been.

For better or worse, those silos survive in the organization because they live in your blind spot as a leader. The last thing you want is for your people to develop effective actionable ideas, only to deliver them to an organization that is unprepared to act on them due to infighting, closed-mindedness, or a fundamental lack of communication across the organization. Russell Weiner, now president of Domino’s Pizza, told me an illuminating story about a corporate executive who called Weiner to ask how the exec’s company could gain back the trust that was lost with a recent data issue. Weiner recounted: “Everything I said I would do, he said, ‘We can’t do that.’ It’s almost like, one of the tests to figure out if what you’re thinking of doing is a good idea is that it scares you a little bit . . . and part of the solution needs to be something that’s big enough.”

Weiner also believes that, in any brand that’s been around long enough, people generally know what’s wrong and what has to change. For instance, cigarette manufacturers clearly harm their customers. The problem is, as Weiner describes, “the honest thing they need to do to fix their business will certainly disrupt their business and could potentially be the end of their business.” I saw this principle firsthand when my agency disrupted our model by inventing Stradeso, a company literally designed to put our agency out of business. Whether that new business does well or not, it was the honest move to make. I know the truth: if I don’t disrupt my own business, my competitors will do it for me. All these organizational issues depend on your continually opening up your blind spot so that you don’t accidentally become your organization’s greatest weakness.

GETTING HONEST WITH YOURSELF MEANS REINVENTING YOURSELF

Entrepreneurs give us a particularly compelling glimpse into how to get brutally honest with ourselves, because founders typically operate all alone. We have no safety nets, usually no board of directors, and no managers to escalate to. Creating a business is one lonely pursuit that puts many founders in and out of despair as their businesses soar and flounder (been there, done that). And because an entrepreneur’s atmosphere is so volatile, it makes for the perfect case study on personal honesty.

When it comes to silos, make no mistake—the end loser is the customer, and there’s an opportunity cost to your organization. When your people divert time and energy toward managing political silos, they’renot focusing on the customer.

After mentoring hundreds of founders, I’ve learned a lot about how blind spots can hide massive threats to an entrepreneur’s vision. Typically, those blind spots hide flaws in the very foundation of the business—who the business serves, what problem it solves, and so on. With 100 percent control over our businesses, our actions can singularly create or destroy massive value, and it’s up to us to pursue personal development so that we can each properly lead. After all, we can only grow our organizations as fast as we grow as their leaders.

I was in my early twenties when my business partner and I started our first company. My team and I started out creating $1,000 television spots for local car dealers. It was exactly as glamorous as you might imagine. And I remember thinking, Wow . . . if we could only sell more $1,000 television spots, we’d be rich! Apparently we hadn’t stopped to do the math on how many television spots it would take to become millionaires . . . and once we did, we embarked on many painful pivots to get the business to the multimillion-dollar mark. The story goes to show how easy it was to slip into thinking that growth was what we wanted, when instead we needed to get honest about what even makes a successful, profitable business in the first place. To answer that, we needed to reinvent ourselves over and over again—from video production company to marketing agency to growth partner. Even that wasn’t enough. As I mentioned earlier, we ended up building Stradeso, a marketing tech platform, out of GEM, our marketing agency, because we got brutally honest about how our industry was evolving; the fact that our customers’ needs were changing; and how much our own model was increasingly coming under fire by the new and the innovative. Those insights, which required business-model-breaking honesty, fueled the next reinvention. It never stops, no matter what business you’re in.

Speaking of, one of the best questions I ask my clients is, “What business are you in?” As we’ve seen, Domino’s Pizza is in the overdelivery business. The Ritz-Carlton is in the hospitality leadership business. And Bridgewater Associates, I would argue, is in the honest communication business. None of these answers has anything to do with the industries of those companies. At my company GEM, we’re in the business of partnership. At Stradeso, we’re in the business of turning problems into projects.

I once asked one of my clients, the owner of a bridal store, this key question at a conference workshop.

“We’re in the bridal business,” she confidently responded.

I assured her that was not the case.

Guessing specificity was the answer, she asked tentatively, “Then we’re in the business of wedding dresses?”

“Not quite . . .” I said. “You just told me all about how you help women feel like stars on their wedding days. You help them walk down the aisle and have their husbands-to-be say, ‘Wow.’ You give them that confident feeling when they’re most vulnerable.” After having led the witness, I asked again, “What business are you in?”

One of the best questions I ask my clients is, “What business are you in?”

She had a light bulb moment that day and went home to build her new business—a business that provides self-esteem, not wedding dresses. Being in the self-esteem business opened up a whole host of strategies that her competitors weren’t even thinking about, from the first interaction with a bride-to-be, to the in-store sales process, to the referral process, and everything in between. If you know what business you’re really in, you can align everything you do to that true insight. But first you have to get honest about what your business is all about in the first place. So what business are you in?

As entrepreneurs, our businesses are extensions of us. Entrepreneurship takes time, patience, and a willingness to improve ourselves every single day. To that end, most of my work with entrepreneurs focuses on keeping them from getting caught by what’s in their blind spots and helping them dig deep into their belief systems to make sure they’re not leading themselves astray. That could be positive or negative; some of my clients could temper their confidence, but for the most part, most need to gain back the confidence lost from doing what I consider to be the hardest job in the world: creating something from nothing as an entrepreneur. If I’ve learned anything, it’s that getting honest with yourself—especially as an entrepreneur—is like solving a Rubik’s Cube; when you think you’ve nailed it, you haven’t, and when you think you’re far off, you’re sometimes only a few turns away from getting yourself and your business into alignment with who you really are, what you really want, and what it really takes to get there.

Don’t think for a second that I’m only talking about entrepreneurs here; leaders of every kind in every organization would do well to take the same level of ownership and honest thinking into their roles, especially if they believe that true leadership means forcing themselves into deep self-reflection about who they are and what they want. Just because entrepreneurs typically have more autonomy doesn’t mean that they’re the only ones who get to dive deeply into their honest selves. Arguably, if you do so in a corporate setting, you would stand out by leaps and bounds, especially if your organization values entrepreneurial thinking. Hopefully I’ve changed your mind a bit about what effective entrepreneurial thinking even looks like: a brutally honest effort to continually define who you are and redefine your business until who you are clicks into place with what you do. Such is the way of a successful business, and such is the way of a fulfilling life.

If you know what business you’re really in, you can align everything you do to that true insight. But first you have to get honest about what your business is all about in the first place. So what business are you in?

If you’re familiar with Shark Tank, you know who Barbara Corcoran is. The successful entrepreneur sold her business for millions in 2001, and since 2009 has been bidding for ideas she likes on the ABC reality TV show. A couple of years ago I worked on one of Corcoran’s start-ups as part of Columbia University’s entrepreneurship program, and she had a great analogy for the lows and highs of starting a business. She said the experience is like a bouncing ball: “The harder it comes down, the higher it bounces back up.” Having had a few of my own tough times, I can certainly attest that the ball does bounce back, no matter how downtrodden the situation may seem. But the most important lesson she shared with me is that there’s only one rule in entrepreneurship (and leadership): “Don’t give up.”

That, right there, is honest advice, from someone who’s certainly not afraid to tell it like it is. If you never give up, the only thing left to do is constantly reinvent. Ask yourself the tough questions, like I had to do when I asked myself how we could design a new business to kill our old one. Even the largest of companies, like Quicken Loans with its Rocket Mortgage product, benefit from consistently reexamining their business model, so make a habit of continually asking whether there might be a better way to build your business (and life). Often, just stepping back to ask that question will illuminate some yet-uncharted ways to success.

ACTIONS TO CONSIDER

ACTIONS TO CONSIDER

1.Get your team together to figure out what business you’re really in—i.e., what emotional value your organization provides for customers after they’ve bought your product or service.

2.Revamp your strategy to align your entire business model, business development process, operations, and more to that one powerful emotional value in order to unlock your next successful pivot.

3.Commit to thinking like a reinventive entrepreneur, continually transforming yourself and your business with honesty instead of simply managing or operating within the status quo.

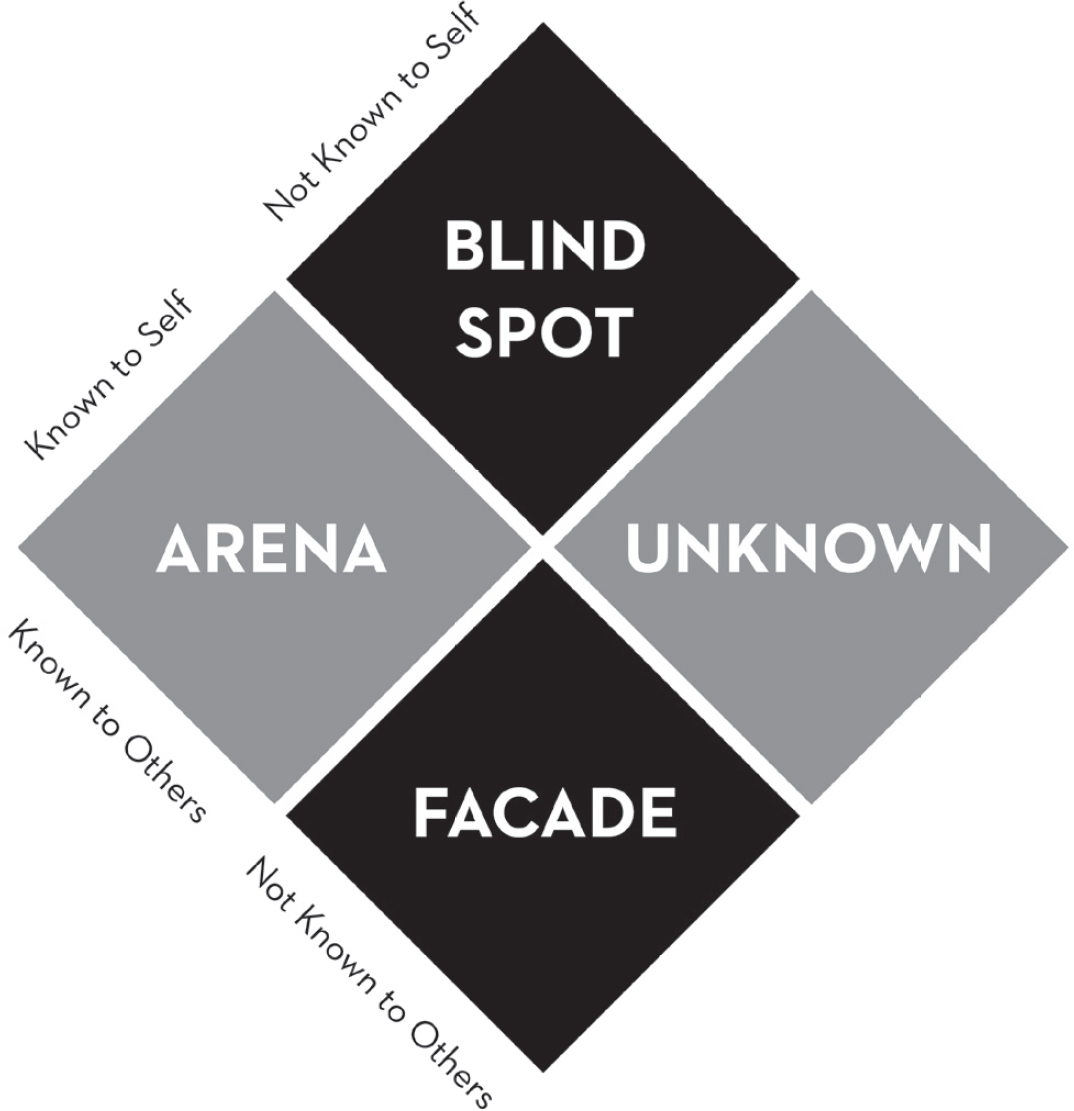

THE JOHARI WINDOW: HOW TO BE A DUMB SHIT IN ORDER TO ACHIEVE GREATNESS

In chapter eleven you learned about the Johari window, which is a framework for understanding that we all have blind spots—things others know about us that we don’t yet recognize in ourselves. If you truly want to ensure that none of your individual self-limiting beliefs or biases get in the way of progress, you’ll have to adopt the same mentality as Bethenny Frankel, Ray Dalio, Jay Farner, and more: I don’t know.

We’ve all heard of the humble leader, but the idea of humility only scratches the surface of getting honest with yourself. As an example, I got humble AF when my agency lost a million-dollar account a few years ago. But the humbling experience of that singular event paled in comparison to the years of self-honesty I experienced after. That one event made me rethink everything—our business model, the people around me, the very idea of happiness itself. Shocks to the system, like losing shit-tons of money, can apparently create some deep self-exploration. But what I really learned was that waiting around for a shock to your system is like waiting to prepare for the hurricane when it’s already upon you. It’s too little, too late, and you’ve only wasted valuable time.

Furthermore, today’s popular 360-degree assessments can only scratch the surface of self-honesty. While helpful to illuminate some blind spots, other issues arise. For instance, Ray Dalio would likely disagree with most executive assessments that are submitted anonymously, because anonymous feedback can skew quickly away from objective truth. Did the anonymous assessor just get their feelings hurt by the subject, encouraging them to retaliate? Is the anonymous assessor using the opportunity to vent frustrations about the subject’s getting a raise ahead of themselves? Is the anonymous assessor guessing about certain character traits based only on what they see on the surface, rather than who the subject actually is? Without transparent, open debate, some assessments could skew the data. And when that data is used to assess an executive’s pay, for instance, everyone might be left worse off than if those debates were brought into the light.

That’s why, as we saw in the last chapter, learning to embrace honest dialogue is so much more effective than hiding in the shadows. And here’s the key: if you aren’t willing to embrace your faults, be vulnerable, and embrace honesty as a leader, you will never be able to create the type of open atmosphere that allows honesty to thrive. In other words, this whole thing starts with you—no matter whether you’re the corner-office boss or not. For better or worse, there are only two ways I’ve found to illuminate my blind spot: first, constantly give it attention, and question, over and over again, what might be living inside it; and second, enlist the help of trusted sources around me who can help me understand which of my beliefs are true and helpful, and which are only getting in the way of my own success.

The Johari Window

Even if you didn’t have the proper term for it, you’ve used the Johari window and peeked into your blind spot before. Think back to a time when you were forced to get honest with yourself—perhaps admitting that you didn’t love that person after all, or you needed that vacation more than you realized, or you couldn’t believe that you cried like a blubbering baby during that movie. You learned something deep about yourself in those moments, and it might have shocked you and even made you feel ashamed or afraid. In those honest, vulnerable moments, you will always learn something new about yourself. And if you listen closely enough to what your inner you is telling you, you just might change your life.

Active listening comes first. You can’t hear what you’re trying to tell yourself unless you learn to block out the noise and home in on your true identity. Remember your core values? If you’re living a life misaligned with those values, chances are you’re miserable. You probably know life has to be better than this. You probably feel like it shouldn’t be this hard. You likely experience an uneasiness in the pit of your stomach, or a dull ache in your heart. That’s when you know you’re not being honest with yourself. I should know—I felt that way for years, like something was misaligned between me and my best life, like there was so much more out there for me to learn and achieve. If you want to know how to get honest with yourself, listen to yourself. Get to know you. Understand who you are and what you want. Because most people don’t. Most people block their own greatness with bullshit, and there’s absolutely no reason at all for inflicting that kind of pain on ourselves.

Don’t be most people; instead, be honest.

With the Right Coach In Your Corner, You Can Change Your Life

I wish I could give you a tidy, five-step formula for getting honest with yourself and opening up your blind spot so you can become a more empowered (and empowering) leader. But I can only offer up a painful path. Mine would look like:

1.Wake up and realize you’ve been lying to yourself about the life you really want.

2.Feel like a complete idiot.

3.Surround yourself with smarter people who can help reveal your blind spots.

4.Figure out what makes people and organizations crush life.

5.Shake off fear, find yourself, and go for what you really, truly want in life.

To be clear, I don’t want you to experience steps one and two, so I’ll pick up at step three, which I’ve found to be the most effective way to get honest with and about yourself—because the truth is, none of us can play psychologist to ourselves. As my business partner always reminds clients: you can’t see yourself from the outside if you’re on the inside. And no, you are not the exception. There are none.

What I learned in the depths of my own self-honesty crisis is that we need coaches to help us see the blind spots we’ve accidentally adopted as parts of our true selves.

What I learned in the depths of my own self-honesty crisis is that we need coaches to help us see the blind spots we’ve accidentally adopted as parts of our true selves. If the most high-performing athletes in the world have coaches, why would we try to perform at our executive best for the majority of our waking lives without people there to guide us? As a leader, your primary role is to coach those who report to you so they can be empowered in your Waterfall Culture to fulfill the mission of the organization. The entire organization depends on your clarity. In turn, your own coach can help you get the perspective you need to perform at your best. It’s like putting your oxygen mask on first before helping others on an airplane.

ACTIONS TO CONSIDER

ACTIONS TO CONSIDER

1.Get a coach who can continually point out your blind spots and help you identify self-limiting beliefs so they don’t accidentally block you from success.

2.Adopt Ray Dalio’s rule “If I’m wrong, I want to know about it” by surrounding yourself with smart people and empowering them to disagree with you so you get to the best outcome instead of your outcome.

3.Post the Johari window in your office and develop a habit of asking yourself of every idea and belief, “Is that actually true?” and “How can I find out?”

Empower Yourself to Empower Others

Some people just aren’t ready to face the facts. You might have even identified some self-limiting beliefs in others, realizing that the people around you might have been lying to themselves. You might have even called them out on it. What happened next?

Without the proper framework in place—educating people about what self-limiting beliefs are and why they matter—you’re assaulting the very essence of a person’s world by telling them that everything they’ve believed for years might be wrong. When you’re confronted with such a radical shift in your worldview, it can feel like experiencing a death . . . the death of your former self. Part of being honest with the self is realizing that each one of us exists on our own spectrum of honesty—and that, as we saw in part one, we all struggle with the truth in ways small and large. In one of the first discussions about what this book could be, my team and I agreed that no one can be forced to be honest; it must come from within.

That said, in the pursuit of making yourself more honest, there’s a manner of speaking you can adopt that puts people at ease and helps them understand your perspective rather than forcing it upon them. When I joined the Entrepreneurs’ Organization, I became part of a Forum of other founders who serve as my sounding board, board of directors, and overall personal bullshit meter. In Forum, we don’t give advice; instead, we only speak from personal experience when suggesting what one might do to improve. Using “I” instead of “you” is a completely disarming language technique that shows others humility and respect. For instance, you might notice that many of these chapters have Actions to Consider and Questions for Honest Reflection. I’m not telling you what to do, because I have no doubt that your situation is unique; instead, I’m asking you to reflect on a few interesting ideas and consider some actions you might take. The difference is subtle but effective.

Every time you tell someone what they should do, their natural response will be to put up their defenses. Watch for “you should” in your daily conversations, and observe what the other person says, does, or feels. Sometimes I can see “you should” land like a linguistic blow to the person’s face; other times they’ll shift uncomfortably or begin to get defensive in their response. If you watch for it and observe what you’re seeing, you might be as horrified as I was to see how important that language is, and how assaulting it can be. This whole idea—the concept of how you humbly interact with others (or don’t)—directly relates to how honest you are with yourself. Removing “you should” from your vernacular signifies that you don’t tell people what they should do, because you, yourself, don’t know. The less we admit to knowing, the more powerful we are. The more we can help light the way for others instead of forcing them down a path that we, ourselves, may not even fully understand, the more effective we will be.

Does it invigorate you to help others succeed? Does it thrill you to open the minds of your colleagues, friends, and family members, so that you can all, together, achieve a business goal or live a more fulfilling life? If so, if you’re truly a leader, then consider vulnerably, openly, and honestly sharing your experiences with others. Consider asking them provocative questions that can help them unearth new insights. Consider guiding people with an invitation to be honest instead of commanding that they be more innovative. After earning my badge as “most likely to continue being a jerk” in high school, I can tell you that being a know-it-all doesn’t make for an honest self. And I can’t fully tell you what does—except that the more I get honest with my own weaknesses and the humbler I become, the more I seem to be able to effectively lead others to greatness.

As you’ve seen, the path to greatness is the same for leaders as it is for organizations. I’ve learned to become comfortable consistently killing my old self and reinventing as a better me, like a phoenix from the ashes. And yeah, it hurts like hell to endure that process, but achieving greatness means pushing boundaries way beyond the comfort of the status quo. Our organizations can metamorphose the same way, again and again, to capitalize on the trends that threaten their existence. To that end, introduce honesty to your team. Show them the Johari window. Help them understand what a blind spot is. Seek the truth together. Share experiences. Just talking about these concepts will help identify some roadblocks that no one even thought to consider.

Or don’t. Or live in the status quo. But at least be honest with yourself about whether you’re going to use brutal honesty to achieve massive success, or not. No matter which one you choose, at least be honest: you have the power to use honesty to change your organization and change your life. Choose wisely.

QUESTIONS FOR HONEST REFLECTION

QUESTIONS FOR HONEST REFLECTION

1.How can you adopt an attitude of humility and openness to begin to identify your self-limiting beliefs and biases?

2.How can you invite a coach or consultant to referee your decisions and call you on your bullshit?

3.How can you introduce honesty to your organization, encourage your people to be honest with themselves and with others, and lead by example by embracing “I don’t know” and eliminating “you should” from your language?